The first-person shooter and the real-time-strategy game, those two genres that had come to absolutely dominate mainstream computer gaming by the end of the 1990s, were surprisingly different in their core technologies. The FPS was all about 3D graphics, as aided and abetted by the new breed of hardware-accelerated 3D cards that seemed to be getting more powerful — and also more expensive — almost by the month. A generation of young men whose fathers might have spent their time tinkering with hot rods in the garage could be found in their studies and bedrooms, trying to outdo their peers by squeezing a little bit more speed and fidelity out of their “rigs”; in this latest era of hot-rodding, frame rate and resolution were the metrics rather than quarter-mile times and dynamometer results.

The technology behind the RTS was fairly traditional by comparison; these games relied on sprites and pixel graphics that weren’t that dissimilar in the broad strokes from the graphics of the 1980s. Running them was less a continuum — less of a question of running a game better or worse — and more a simple binary divide between a computer that could run a given game at an acceptable speed and one that could not. If you happened to be a fan of both dominant genres, as plenty of people were, your snazzy new 3D card had to sit idle when you took a break from Quake or Half-Life to fire up Command & Conquer or Starcraft.

Still, one didn’t have to be much of a tech visionary to see that the unique affordances of 3D graphics could be applied to many other gameplay formulas beyond running around and shooting things from an embodied first-person perspective. The 3D revolution offered a whole slate of temptations to RTS makers and players. Instead of staring down on a battlefield from a fixed isometric view, you could pan around to view it from whatever angle made most sense in the current situation. You could zoom in to micro-manage a skirmish in detail, then zoom out to take in the whole strategic panorama. Embracing the third dimension in graphics promised to bring a whole new dimension of play and spectacle to the RTS. Already in 1997, RTS games like Total Annihilation and Myth: The Fallen Lords were making some use of 3D technology to bring some of those features to the table.

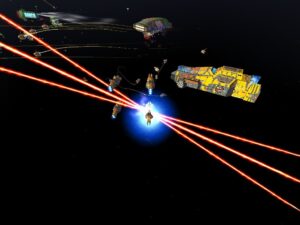

But it wasn’t until Homeworld, a game developed by Relic Entertainment and published by Sierra in late 1999, that an RTS went all-in on 3D, moving the battlefield from the surface of a planet to the infinite depths of space, where up could just as easily be down, or left, or right. Such an experiment was surely inevitable; if these folks hadn’t done it when they did, someone else would have soon enough. What feels far less predestined is how fully-formed this first maximally 3D RTS was, so much so that it would never be comprehensively surpassed in the opinion of some fans of the genre. This is highly unusual in game development, where innovations more typically make their debut complete with plenty of rough edges, which need a few iterations to be sanded down to friction-less perfection. Homeworld, however, was a seemingly immaculate conception, the full package of technology and design right out of the gate. It frustrated the competition by leaving them with so little to improve upon. And it did something else as well, something guaranteed to endear it to me: in an era and a genre in which narrative was widely debased and dismissed, it showed how much a well-presented, intelligent story could do to elevate a game.

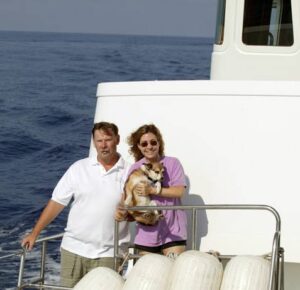

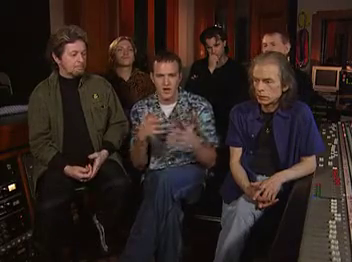

The folks from Relic Entertainment who made Homeworld. Alex Garden is at center right, wearing blue jeans and a black pullover.

Most games begin with a gameplay genre: I want to make an FPS, or an RTS, or a CRPG. (Gamers do love to make an alphabet soup out of their hobby, don’t they?) But some games — including many of the most special ones — begin instead with an experience their makers wish to offer their players, then let that dictate the mechanics. It feels appropriate that Homeworld, notwithstanding its status as the canonical first 3D RTS, started the latter way, in the head of a 21-year-old Canadian named Alex Garden in the spring of 1997.

Despite his tender age, Garden thought of himself as a grizzled industry survivor, having been involved with games for five years. He had first been hired as a games tester at Distinctive Software, based right there in his hometown of Vancouver, after he met Distinctive’s founder Don Mattrick in the frozen-yogurt shop where he was working at the time. Half a decade later, he had become a software engineer at Electronic Arts Canada, the new incarnation of Distinctive, working primarily on the Triple Play series of baseball games. But Garden was a young man with big ideas, equipped with a personality big enough to sell them. He was already itching to strike out on his own and try to bring some of them to fruition.

Garden was a big fan of the old but sneakily influential 1978 television show Battlestar Galactica. One of the first pieces of media to capitalize on the craze for science fiction ignited by the original Star Wars, it was irredeemably cheesy in many respects, boasting characters with names like “Apollo” and “Starbuck” and the obligatory insufferable kid with a robot dog. But its visual effects were exceptional for the era; it offered up the most exciting pictures of combat in space that anyone had seen on a screen since its inspiration had dazzled moviegoers a year earlier. Then, too, there was a vein of myth that ran beneath all of the surface cheese to lend the show an odd sort of gravitas. Creator Glen A. Larson was a devout Mormon, and he based his semi-serialized story on that of the twelve wandering tribes of Israel, as well as the so-called Mormon Exodus, the overland trek of Brigham Young and his followers from Illinois to Utah in the mid-nineteenth century. In the show, a “ragtag fleet” of humans who look just like us seek a new home after their planet has been destroyed by the evil Cylons, a robotic race of aliens who continue to harry them even now. This new planet the humans search for is called — wait for it! — Earth, purported to be the home of a legendary “thirteenth tribe of humanity.”

You might be inclined to dismiss it all as just the usual claptrap about “ancient astronauts” and the like, one more misbegotten spawn of Erich von Däniken’s wildly popular book of pseudo-archaeology Chariots of the Gods, and I wouldn’t rush to argue with you. But to Star Wars-loving youngsters, all those portentous voiceovers gave the show a weighty resonance that even their favorite film couldn’t match. Battlestar Galactica lasted just one season on the air; its ratings weren’t terrible, but were deemed not sufficient to justify the $1 million per episode the show cost to produce. Yet it had a profound impact on some of those who saw it, both during its short prime-time run and during the decades it spent as a fixture of syndicated television thereafter. Among these people was our old friend Chris Roberts, who lifted its conceit of “World War II aircraft carriers in space” for Wing Commander, the biggest computer-game franchise of the early 1990s. And to that same list we can now add Alex Garden, who would appropriate less its surface trappings and more its deeper theme of ragtag refugees searching for a home.

To hear Garden tell the tale, the trip from Battlestar Galactica to Homeworld was a quick and logical one.

I was having a conversation with some friends about how much we loved Battlestar Galactica, and wouldn’t it be great if it was back on TV. We were also talking about how much we loved X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter, but how all you could do was pull back, pull left, and so on. So I started thinking to myself, “Wouldn’t it be great if you could have a 3D game that looked like you were watching Star Wars but had a story line like Battlestar Galactica?” And the game just came to me. Like a flash.

The idea, then, was to use 3D graphics in a different way from the norm, liberating you from a single embodied perspective and letting you roam free around and through a space battle, the way that the cameras of George Lucas and Glen Larsen were allowed to do. But at the same time, there would be more than spectacle to Homeworld. The story was key to Garden’s vision in a way that it wasn’t for most working in the RTS genre, where the single-player campaigns often seemed like mere training exercises to prepare you for the real point of the endeavor, the online multiplayer component.

Garden may have been young and unproven, but he could be very persuasive, and the blueprint for a 3D RTS that he was selling was both bracing and a fairly obvious next technological step for the suddenly ascendant genre as Warcraft II and Command & Conquer were tearing up the sales charts. On the strength of “two whiteboard presentations and no demo,” he signed a contract with Sierra On-Line, freshly pried out of the clutches of its founders Ken and Roberta Williams and ready to leave its roots in adventure games behind and go where the present-day action in gaming was. Sierra would endure a wild roller-coaster ride during the 28 months that Homeworld would spend in development, encompassing a vexed merger, a massive financial scandal, and finally another sale. Yet all of this affected Relic Entertainment, the little studio that Alex Garden founded above a nightclub in Vancouver in order to make Homeworld a reality, less than one might expect. He and the twenty or so compatriots he gathered around him just kept their heads down and kept on keeping on. Garden evinced a wisdom far beyond his years when he described his approach to leadership: “Figure out what you’re good at, assume you’re lousy at everything else, hire people to do all the things you’re lousy at, and get out of their way.”

Anyway, they had way too much to worry about in the realms of technology and design to pay much attention to corporate politics. Although most of the core gameplay concepts in Homeworld would be familiar to any RTS veteran, their implementation in 3D was uncharted territory. All past games that had tried to model space combat from an admiral’s point of view, dating back to tabletop classics like Star Fleet Battles, had struggled with the third dimension, consigned as they were to playing out on a 2D canvas. The most typical solution had been to more or less ignore the dimension of depth, to present space combat as if these were dreadnoughts floating on an ebony ocean rather than the inhabitants of an environment where up, down, left, and right were all available options at all times, and all strictly a matter of one’s current perspective on the battlefield. Needless to say, this wouldn’t do for Homeworld. How to present this three-dimensional battlefield in a way that human gamers, sad terrestrial creatures that they were, could grasp and manipulate?

They settled on an interface that stayed invisible most of the time. The screen was filled entirely with the open vista of space, through which you would ideally roam by taking advantage of one of the more baroque mice that were just starting to replace the basic two-button rodents on many new computers. You rotated the view by holding down the right button and moving the mouse; zoomed in and out using the mouse wheel; set the camera to follow a ship by clicking it with the middle button. You issued orders to your vessels by left-clicking them to select them and then right-clicking to bring up context menus — or, even better, by learning the keyboard shortcuts to the various commands. Initially, it could make for a disorienting mixture of old and new. “We found players who had very little exposure to top-down RTS games had an easier time learning the controls to Homeworld,” admits Erin Daly, lead designer of the game and the very first employee hired by Relic to join Alex Garden there above the nightclub. Once you spent some time with it, though, the interface began to seem less baffling and, indeed, the only reasonable one.

Homeworld was built as a multiplayer game first, in order to get the core gameplay working without having to think above the vagaries of artificial intelligence. Yet Alex Garden’s determination to make it a compelling, immersive fiction in addition to a place to fight with your buddies never wavered. He entrusted the world-building to a 27-year-old anthropologist, archaeologist, and part-time science-fiction writer named Arinn Dembo, the manual and the in-game script to a 32-year-old games journalist named Martin Cirulis. They made the setting and the story as rich as Garden could possibly have hoped for — in fact, far outdistancing Battlestar Galactica in detail and coherency. The eventual manual would open with 40 pages of “historical and technical briefings” in small type. At the end of the day, Homeworld may still have been a game about blowing things up in outer space, a theme handed down from the original Space Invaders, but it was going to try its darnedest to give the explosions some contextual resonance.

This isn’t to say that the story was the first thing that leaped out at the legions of eager gaming scribes who started to write about Homeworld in the magazines already more than a year before its release. And in truth it’s hard to blame them: even in its formative stages, Homeworld looked absolutely amazing, like nothing else out there. It remains a wonderland of heavenly delights for screen-shooters, presenting an endless series of striking tableaux that are each unique, because each of them stems from your game and no one else’s.

The many published previews provide us with a rare window into Homeworld’s development. Most of all, they tell us how stable the core tenets of the design remained; by the time the first journalists came through the door, all of the fundamentals of the gameplay were in place, leaving only the endless labor of refining, refining, refining. “We had the basic control scheme nailed on day one,” laughed Alex Garden later. “Ironing out the details of that basic scheme was a simple two-year task…”

The structure of the campaign is the one place where the design was overhauled in a more dramatic way. It was first envisioned as a somewhat non-linear affair that would let players literally pick their battles as they guided their fleet from star system to star system in search of home. In the end, though, this meta-game was abandoned in favor of a more standard fixed ladder of increasingly difficult scenarios. But one important twist on the standard RTS campaign formula did survive: instead of starting each scenario from scratch, researching the same technologies and building a fleet of the same old units, you would be able to take both your current tech tree and your current fleet with you from scenario to scenario. This makes a huge difference to the overall experience, about which more in a moment.

Undoubtedly the strangest outcome of the mounting hype over Homeworld was a partnership with, of all people, the venerable rock group Yes. Prior to this point, it had been game developers who had sought comparisons and collaborations with rock stars, not the other way around. In this case, however, the initial overture came from the musicians’ side. It seems that Jon Anderson, Yes’s lead singer, had decided that an association with a computer game might be a good way to promote his band’s next album. He directed his publicist to shop the idea around the industry. It was an odd avenue of promotion on the face of it, but not completely inexplicable when you thought it through. After a reign as one of the most popular progressive-rock bands on the planet during the heyday of that style in the 1970s, releasing albums where the ten-minute tracks were sometimes the short ones, Yes had managed to pull off an opportunistic transformation in the 1980s, into sleek, New Wave-inflected pop hit-makers. Alas, the 1990s had been less welcoming, seeing Yes caught between their two identities amid ever-shifting personnel lineups, awakening only indifference outside of their dwindling hardcore fan base. With their days of getting radio play long behind them, it perhaps wasn’t so unreasonable to try to capture the attention of computer gamers, whose Venn diagram was known to have a significant overlap with that of prog-rock listeners.

Jon Anderson’s inquiries eventually led him to Sierra, who passed him on to Relic Entertainment. He came out to Vancouver to spend a day looking at Homeworld and discussing the story, although it’s questionable how deeply he understood either; he “loved” the story, he later said, because “the story line was very similar to thoughts common to human beings. We’re all trying to find our way home.” But for a songwriter famous for his nonsensical lyrics (“In and around the lake, mountains come out of the sky and stand there…”), it probably didn’t matter all that much one way or the other. He patched together several shorter songs to make one long one called, appropriately enough, “Homeworld.” (“Just what keeps us so alive, just what makes us realize, our home is our world, our life, home is our world…”) “It was really all about getting people who had enjoyed Yes in the ’70s to come back,” Anderson says. And indeed, the track does feel more like fan service than a vital artistic statement, a description which can be applied to most of the band’s latter-day efforts.

One of these people doesn’t belong here: Alex Garden, center, visits Yes in the studio. Jon Anderson, left, speaks for his bandmates, who positively radiate their disinterest.

Be that as it may, “Homeworld” was the lead-off track on Yes’s album The Ladder, which was released on September 20, 1999. A demo of the game was included on the CD. When the full game shipped just a week later, it included promotional materials advertising The Ladder as “a striking return to form for the band” (the same words that would be used to describe every subsequent Yes album for the next quarter-century, as it happened). The song played over the game’s credits sequence. When all was said and done, it seems doubtful whether the odd cross-promotional strategy did much of anything for either Relic or Yes. Homeworld sold over half a million copies in its first six months; The Ladder sold rather less well.

But if the Yes song turned out to be kind of pointless, there was very little else in the game about which one could make the same statement. Homeworld is a marvel of focused design, a game which knows exactly what it wants to do and be, and achieves every one of its goals with grace and verve. I must admit that I didn’t finish it, but that says more about the player than it does about the game; as most of you know by now, I have no natural affinity or talent whatsoever for the RTS genre, and in the end I just had too many other games on the syllabus to spend any more time struggling with this one, which becomes very challenging by its middle phases.

Given how rubbish I am at the genre, I’m woefully unqualified to write in detail about Homeworld’s mechanical merits as an RTS; suffice to say that, while the learning curve is a bit steep for my tastes, Homeworld is amazingly mature for being the first of its 3D breed. What I’d like to drill down on here is something closer to my heart: the incredible extent to which it succeeds as a lived fictional experience. To my knowledge, no other RTS of its era comes close to it in this respect. Command & Conquer, Warcraft I and II, even to a large degree Starcraft… all had campaigns that served more as excuses for their scenarios — or, in the case of Command & Conquer, excuses for the creators to make the deliriously campy B-movies of their dreams — than compelling fictions in their own right. Homeworld is not like that. Even once the gameplay had worn me out, I still had to see the story through on YouTube, simply because I wanted to know what would happen. There are very, very few ludic fictions, from any gameplay genre, about which I can make such a statement.

Homeworld is about a group of humans from a planet called Kharak, for whom the “ancient astronauts” theory promulgated by Erich von Däniken here on Planet Earth turned out to actually be true. For there came a point when the steady march of their science “revealed a disturbing lack of commonality between our biochemical makeup and that of most Kharakid life.” Their satellites found “unusual pieces of metallic debris in high orbit,” containing “trace elements and isotope combinations unknown on Kharak.” Finally, the remnants of an enormous interstellar spaceship were found buried beneath the surface of the planet. Amidst the wreckage there was unearthed the “Guidestone,” an artifact engraved with a map of the known galaxy, highlighting Kharak and another planet labeled as Hiigara, a word meaning “Home.”

Using knowledge scavenged from the wreckage, the Kharakids spent more than a century constructing an interstellar vessel of their own, a “Mothership” capable of carrying up to 600,000 souls, suspended in cryogenic sleep, to this lost home world of Hiigara. The Mothership is a mobile factory as well as a colony ship, able to produce more, smaller ships from mined materials. (Anyone who has ever stood within ten feet of an RTS can probably sense where this is going…) It is controlled by a neuroscientist named Karan Sjet, who has volunteered to have her own brain wired into its computer systems. Karan Sjet is you, of course.

So, the campaign is about the Mothership’s search for home. The fact that your fleet and your research progress carry over from scenario to scenario makes it feel like one seamless story, epic in a way that smacks more of Civilization than Starcraft. Major plot developments occur within the scenarios more often than between them, further breaking down the standard RTS drill of mission briefing, mission, and victory screen. Individual ships become known to you for their exploits, even as they learn to fly and fight better over time. You develop a real attachment to them in much the same way you might to, say, the soldiers you send into battle in XCOM; you’ll find yourself looking out for them, trying to minimize their exposure to danger just as any humane real-world admiral would. In my admittedly limited experience, none of these feelings are at all typical of the RTS genre.

That said, a disarming amount of Homeworld’s success as a fiction comes down to its aesthetic presentation. In a genre known for its frenetic pace, built around scenarios that are considered to have overstayed their welcome if they stretch out to more than half an hour, this game is willing to take its time, with scenarios that can take several hours to finish. Everything is slower, more stately, allowing you plenty of opportunity to… well, to simply contemplate the scene before you, to think about where you have been and where you are going. The vibe is more 2001: A Space Odyssey than Star Wars or Battlestar Galactica, weird as that may sound for a game that is ultimately still about blowing things up in space. Relic made the bold choice of building the soundtrack around moody synths, strings, and choral voicings, eschewing the clichéd heavy-metal guitar riffs and techno beats that dominated the RTS scene. The choice lends the game a timeless dignity. Its real theme song isn’t the busybody Yes tune, but rather the elegiac strains of Samuel Barber’s 1936 Adagio for Strings, the only other piece of music in the soundtrack not composed by Paul Ruskay of Vancouver’s Studio X Production Labs. Combined with the visuals, which radiate their own stately beauty, the music makes Homeworld feel like the lone adult in a genre full of screeching adolescents. Even the voice-acting is more subdued and mature than the RTS norm — no sign of Starcraft’s cigar-chomping space marines here. In a genre known for having all of its aesthetic dials set to eleven all the time, Homeworld understands that grace notes can be more affecting than power chords.

I want to tell you about what I found to be the most jaw-dropping moment of the game, but, in order to do so, I do need to spoil the first stage of the campaign just a little bit. So, if you haven’t played Homeworld, think you might want to, and want to go in completely cold, skip to just beyond the video below….

The first two scenarios of the campaign are essentially extensions of the tutorial, in which you take the Mothership on a shakedown cruise before embarking on the long voyage in search of Hiigara. In the third scenario, you return to Kharak to take the colonists aboard and make final preparations for the real odyssey. But you are greeted there with the rudest of all imaginable awakenings: your people’s return to interstellar space has activated an ancient tripwire, prompting a race of aliens known as the Taiidan to come to your defenseless planet and pound it into uninhabitability. You’re thrown into a race to collect as many as possible of the cryogenic modules holding the sleeping colonists, which have already been fired into orbit, before the attackers destroy them as well. But this happens, like almost everything else in Homeworld, at an almost paradoxically stately pace, leaving plenty of the aforementioned room for contemplation. A wind of tragedy that Aeschylus would have understood blows through the whole thing. There is no triumphant fanfare at the end, just the quiet words, “There’s nothing left for us here. Let’s go.” Wow.

Thinking back on it, I realize that I want to set Homeworld up alongside Half-Life and FreeSpace 1 and 2 as a sort of late-1990s triptych of games that dared to do more with their fictions than anyone could ever have expected of them. All three of these titles are unabashedly difficult games aimed pretty firmly at the hardcore cognoscenti, working within action-oriented genres not particularly known for their aesthetic or thematic sophistication. And yet they all found ways to make us care about what we were seeing on the monitor screen on a deeper level than that of high scores and bragging rights. They have, for lack of a better word, gravitas. Less ideally, all three make me wish I had the time to get better at their individual forms of gameplay, so I would be better equipped to experience them as they were meant to be. But even failing that, it makes me happy to know that the old Infocom ideal of “waking up inside a story” still lived on amidst the deathmatches and corporate mergers of the turn of the millennium.

If you’re an RTS fan, you owe it to yourself to give Homeworld a shot. And if you’re not… well, you should probably play at least some of it anyway, just to get a taste of its incredible audacity and uncanny beauty. Art, after all, is where you find it.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Close to the Edge: The Story of Yes by Chris Welch and Game Design: Secrets of the Sages (2nd ed.) by Marc Saltzman; Computer Gaming World of September 1998 and January 2000; Sierra’s customer newsletter InterAction of August 1998 and Spring 1999; Game Trade 23; Next Generation of August 1998; PC Zone of July 1998, February 1999, and November 1999.

Online sources include a video advertisement for Yes’s Ladder album and one dealing more directly with the “Homeworld,” a Homeworld retrospective by John Beford for Eurogamer, “Games That Changed the World: Homeworld“ at the old Computer and Video Games site, and a tribute to Glen A. Larsen by Jim Bennett at Deseret News.

Where to Get It: A Homeworld Remastered Collection at GOG.com includes the unaltered original game as a bonus, should you want to play it as people did back in 1999. And you might just want to: the remaster makes some significant gameplay changes which don’t thrill everybody.