The French creative aesthetic has always been a bit different from that of English-speaking nations. In their paintings, films, even furniture, the French often discard the stodgy literalism that is so characteristic of Anglo art in favor of something more attenuated, where impression becomes more important than objective reality. A French art film doesn’t come off as a complete non sequitur to Anglo eyes in the way that, say, a Bollywood or Egyptian production can. Yet the effect it creates is in its way much more disorienting: it seems on the surface to be something recognizable and predictable, but suddenly zigs where we expect it to zag. In particular, it may show disconcertingly little interest in the logic of plot, that central concern of Anglo film. What affects what and why is of far less interest to a filmmaker like, say, François Truffaut than the emotional affect of the whole.

Crude though such stereotypes may be, when the French discovered computer games they did nothing to disprove them. For a long time, saying a game was French was a shorthand way for an Anglo to say that it was, well, kind of weird, off-kilter in a way that made it hard to judge whether the game or the player was at fault. Vintage French games weren’t always the most polished or balanced of designs, yet they must still be lauded today for their willingness to paint in emotional colors more variegated than the trite primary ones of fight or flight, laugh or cry. Such was certainly the case with Éric Chahi’s Another World.

France blazed its own trail through the earliest years of the digital revolution. Most people there caught their first glimpse of the digital future not through a home computer but through a remarkable online service called Minitel, a network of dumb terminals that was operated by the French postal and telephone service. Millions of people installed one of the free terminals in their home, making Minitel the most widely used online service in the world during the 1980s, dwarfing even the likes of CompuServe in the United States. Those in France who craved the capabilities of a full-fledged computer, meanwhile, largely rejected the Sinclair Spectrums and Commodore 64s that were sweeping the rest of Europe in favor of less universal lines like the Amstrad CPC and the Oric-1. Apple as well, all but unheard of across most of Europe, established an early beachhead in France, thanks to the efforts of a hard-charging and very Gallic general manager named Jean-Louis Gassée, who would later play a major role in shepherding the Macintosh to popularity in the United States.

In the second half of the 1980s, French hardware did begin to converge, albeit slowly, with that in use in the rest of Europe. The Commodore Amiga and Atari ST, the leading gaming computers in Europe as a whole, were embraced to at least some extent in France as well. By 1992, 250,000 Amigas were in French homes. This figure might not have compared very well to the 2.5 million of them in Britain and Germany by that point, but it was more than enough to fuel a thriving little Amiga game-development community that was already several years old. “Our games didn’t have the excellent gameplay of original English-language games,” remembers French game designer Philippe Ulrich, “but their aesthetics were superior, which spawned the term ‘The French Touch’ — later reused by musicians such as Daft Punk and Air.”

Many Amiga and ST owners had been introduced to the indelibly French perspective on games as early as 1988. That was the year of Captain Blood, which cast the player in the role of a clone doomed to die unless he could pool his vital essences with those of five other clones scattered across the galaxy — an existential quest for identity to replace the conquer-the-galaxy themes of most science-fiction games. If that alone wasn’t weird enough, the gameplay consisted mostly of talking to aliens using a strange constructed language of hieroglyphs devised by the game’s developers.

Such avoidance of in-game text, whether done as a practical method of easing the problems of localization or just out of the long-established French ambivalence toward translation from their mother tongue, would become a hallmark of the games that followed, as would a willingness to tackle subject matter that no one else would touch. The French didn’t so much reject traditional videogame themes and genres as filter them through their own sensibilities. Often, this meant reflecting American culture back upon itself in ways that could be both unsettling and illuminating. North & South, for instance, turned the Civil War, that greatest tragedy of American history, into a manic slapstick satire. For any American kid raised on a diet of exceptionalism and solemn patriotism, this was deeply, deeply strange stuff.

The creator of Another World, perhaps the ultimate example of the French Touch in games, was, as all of us must be, a product of his environment. Éric Chahi had turned ten the year that Star Wars dropped, marking the emergence of a transnational culture of blockbuster media, and he was no more immune to its charms than were other little boys all over the world. Yet he viewed that very American film through a very French lens. He liked the rhythm and the look of the thing — the way the camera panned across an endless vista of peaceful space down into a scene of battle at the beginning; the riff on Triumph of the Will that is the medal ceremony at the end — much more than he cared about the plot. His most famous work would evince this same rather non-Anglo sense of aesthetic priorities, playing with the trappings of American sci-fi pop culture but skewing them in a distinctly French way.

But first, there would be other games. From the moment Chahi discovered computers several years after Star Wars, he was smitten. “During school holidays, I didn’t see much of the sun,” he says. “Programming quickly became an obsession, and I spent around seventeen hours a day in front of a computer screen.” The nascent French games industry may have been rather insular, but that just made it if anything even more wide-open for a young man like himself than were those of other countries. Chahi was soon seeing the games he wrote — from platformers to text adventures — published on France’s oddball collection of viable 8-bit platforms. His trump card as a developer was a second talent that set him apart from the other hotshot bedroom coders: he was also a superb artist, whether working in pixels or in more traditional materials. Although none of his quickie 8-bit games became big hits, his industry connections did bring him to the attention of a new company called Delphine Software in 1988.

Delphine Software was about as stereotypically French a development house as can be imagined. It was a spinoff of Delphine Records, whose cash cow was the bizarrely popular easy-listening pianist Richard Clayderman, a sort of modern-day European Liberace who would come to sell 150 million records by 2006. Paul de Senneville, the owner of Delphine Records, was himself a composer and musician. Artist that he was, he gave his new software arm virtually complete freedom to make whatever games they felt like making. Their Paris offices looked like a hip recording studio; Chahi remembers “red carpet at the entrance, gold discs everywhere, and many eccentric contemporary art pieces.”

He had been hired by Delphine on the basis of his artistic rather than his programming talent, to illustrate a point-and-click adventure game with the grandiose title of Les Voyageurs du Temps: La Menace (“The Time Travelers: The Menace”), later to be released in English under the punchier name of Future Wars. Inspired by the Sierra graphic adventures of the time, it was nevertheless all French: absolutely beautiful to look at — Chahi’s illustrations were nothing short of mouth-watering — but more problematic to play, with a weird interface, weirder plot, and puzzles that were weirdest of all. As such, it stands today as a template for another decade and change of similarly baffling French graphic adventures to come, from companies like Coktel Vision as well as Delphine themselves.

But the important thing from Chahi’s perspective was that the game became a hit all across Europe upon its release in mid-1989, entirely on the basis of his stunning work as its illustrator. He had finally broken through. Yet anyone who expected him to capitalize on that breakthrough in the usual way, by settling into a nice, steady career as Delphine’s illustrator in residence, didn’t understand his artist’s temperament. He decided he wanted to make a big, ambitious game of his own all by himself — a true auteur’s statement. “I felt that I had something very personal to communicate,” he says, “and in order to bring my vision to others I had to develop the title on my own.” Like Marcel Proust holed up in his famous cork-lined Paris apartment, scribbling frantically away on In Search of Lost Time, Chahi would spend the next two years in his parents’ basement, working sixteen, seventeen, eighteen hours per day on Another World. He began with just two fixed ideas: he wanted to make a “cinematic” science-fiction game, and he wanted to do it using polygonal graphics.

Articles like this one throw around terms like “polygonal graphics” an awful lot, and their meanings may not always be clear to everyday readers. So, let’s begin by asking what separated the type of graphics Chahi now proposed to make from those he had been making before.

The pictures that Chahi had created for Future Wars were what is often referred to as pixel graphics. To make them, the artist loads a paint program, such as the Amiga’s beloved Deluxe Paint, and manipulates the actual onscreen pixels to create a background scene. Animation is accomplished using sprites: additional, smaller pictures that are overlaid onto the background scene and moved around as needed. On many computers of the 1980s, including the Amiga on which Chahi was working, sprites were implemented in hardware for efficiency’s sake. On other computers, such as the IBM PC and the Atari ST, they had to be conjured up, rather less efficiently, in software. Either way, though, the basic concept is the same.

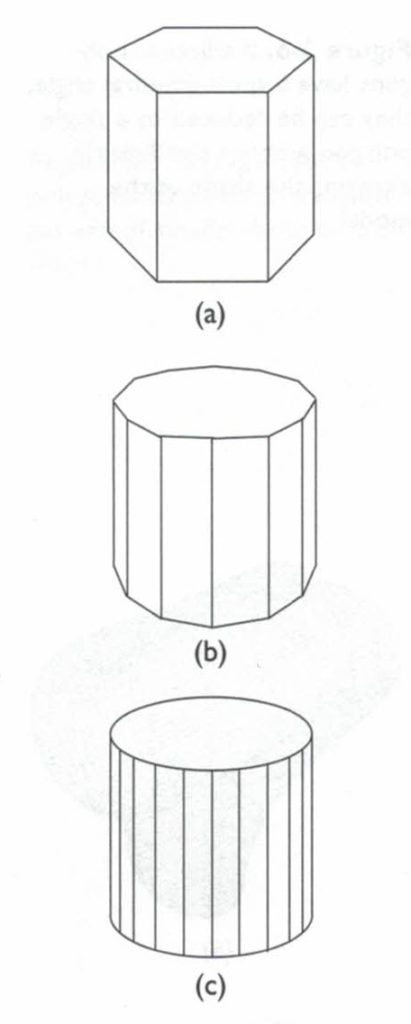

The artist who works with polygonal graphics, on the other hand, doesn’t directly manipulate onscreen pixels. Instead she defines her “pictures” mathematically. She builds scenes out of geometric polygons of three sides or more, defined as three or more connected points, or sets of X, Y, and Z coordinates in abstract space. At run time, the computer renders all this data into an image on the monitor screen, mapping it onto physical pixels from the perspective of a “camera” that’s anchored at some point in space and pointed in a defined direction. Give a system like this one enough polygons to render, and it can create scenes of amazing complexity.

Still, it does seem like a roundabout way of approaching things, doesn’t it? Why, you may be wondering, would anyone choose to use polygonal graphics instead of just painting scenes with a conventional paint program? Well, the potential benefits are actually enormous. Polygonal graphics are a far more flexible, dynamic form of computer graphics. Whereas in the case of a pixel-art background you’re stuck with the perspective and distance the artist chose to illustrate, you can view a polygonal scene in all sorts of different ways simply by telling the computer where in space the “camera” is hanging. A polygonal scene, in other words, is more like a virtual space than a conventional illustration — a space you can move through, and that can in turn move around you, just by changing a few numbers. And it has the additional advantage that, being defined only as a collection of anchoring points for the polygons that make it up rather than needing to explicitly describe the color of every single pixel, it usually takes up much less disk space as well.

With that knowledge to hand, you might be tempted to reverse the question of the previous paragraph, and ask why anyone wouldn’t want to use polygonal graphics. In fact, polygonal graphics of one form or another had been in use on computers since the 1960s, and were hardly unheard of in the games industry of the 1980s. They were most commonly found in vehicular simulators like subLOGIC’s Flight Simulator, which needed to provide a constantly changing out-the-cockpit view of their worlds. More famously in Europe, Elite, one of the biggest games of the decade, also built its intense space battles out of polygons.

The fact is, though, that polygonal graphics have some significant disadvantages to go along with their advantages, and these were magnified by the limited hardware of the era. Rendering a scene out of polygons was mathematically intensive in comparison to the pixel-graphic-backgrounds-and-sprites approach, pushing an 8-bit or even 16-bit CPU (like the Motorola 68000 in the Amiga) hard. It was for this reason that early versions of Flight Simulator and Elite and many other polygonal games rendered their worlds only as wire-frame graphics; there just wasn’t enough horsepower to draw in solid surfaces and still maintain a decent frame rate.

And there were other drawbacks. The individual polygons from which scenes were formed were all flat surfaces; there was no concept of smooth curvature in the mathematics that underlay them. [1]More modern polygonal-graphics implementations do make use of something called splines to allow for curvature, but these weren’t practical to implement using 1980s and early 1990s computers. But the natural world, of course, is made up of almost nothing but curves. The only way to compensate for this disparity was to use many small polygons, packed so closely together that their flat surfaces took on the appearance of curvature to the eye. Yet increasing the polygon count in this way increased the burden of rendering it all on the poor overtaxed CPUs of the day — a burden that quickly became untenable. In practice, then, polygonal graphics took on a distinctive angular, artificial appearance, whose sense of artificiality was only enhanced by the uniform blotches of color in which they were drawn. [2]Again, the state of the art in modern polygonal graphics is much different today in this area than it was in Another World‘s time. Today textures are mapped on polygonal surfaces to create a more realistic appearance, and scenes are illuminated by light sources that produce realistic shadings and shadows across the whole. But all of this was hopelessly far beyond what Chahi or anyone else of Another World’s era could hope to implement in a game which needed to be interactive and to run at a reasonable speed.

These illustrations show how an object can be made to appear rounded by making it out of a sufficient number of flat polygons. The problem is that each additional polygon which must be rendered taxes the processor that much more.

For all these reasons, polygonal graphics were mostly confined to the sort of first-person-perspective games, like those aforementioned vehicular simulators and some British action-adventures, which couldn’t avoid using them. But Chahi would buck the trend by using them for his own third-person-perspective game. Their unique affordances and limitations would stamp Another World just as much as its creator’s own personality, giving the game’s environments the haunting, angular vagueness of a dream landscape. The effect is further enhanced by Chahi’s use of a muted, almost pastel palette of just 16 colors and an evocative, minimalist score by Jean-François Freitas — the only part of the game that wasn’t created by Chahi himself. Although you’re constantly threatened with death — and, indeed, will die over and over in the course of puzzling your way through the game — it all operates on the level of impression rather than reality.

According to some theories of visual art, the line between merely duplicating reality and conveying impressions of reality is the one that separates the draftsman from the artist. If so, Another World‘s visuals betray an aesthetic sophistication rarely seen in computer games of its era. While other games strained to portray violence with ever more realism, Another World went another way entirely, creating an affect that’s difficult to put into words — a quality which is itself another telltale sign of Art. Chahi:

Polygon techniques are great for animation, but the price you pay is the lack of detail. Because I couldn’t include much detail, I decided to work with the player’s imagination, creating suggestive content instead of being highly descriptive. That’s why, for example, the beast in the first scene is impressive even if it is only a big black shape. The visual style of Another World is really descended from the black-and-white comic-book style, where shape and volume are suggested in a very subtle way. By doing Another World, I learned a lot about suggestion. I learned that the medium is the player’s own imagination.

To make his suggestive rather than realistic graphics, Chahi spent much time first making tools, beginning with an editor written in a variant of BASIC. The editor’s output was then rendered in the game in assembly language for the sake of speed, with the logic of it all controlled using a custom script language of Chahi’s own devising. This approach would prove a godsend when it came time to port the game to platforms other than the Amiga; a would-be porter merely had to recreate the rendering engine on a new platform, making it capable of interpreting Chahi’s original polygonal-graphics data and scripts. Thus Another World was, in addition to being a game, actually a new cross-platform game engine as well, albeit one that would only be used for a single title.

Some of the graphics had their point of origin in the real world, having been captured using a long-established animation technique known as rotoscoping: tracing the outlines, frame by frame, of real people or objects filmed in motion, to form the basis of their animated equivalents. Regular readers of this blog may recall that Jordan Mechner used the same technique as far back as 1983 to create the characters in his cinematic karate game Karateka. Yet the differences between the two young developers’ approaches to the technique says much about the march of technology between 1983 and 1989.

Mechner shot his source footage on real film, then used a mechanical Moviola editing machine, a staple of conventional filmmakers for decades, to isolate and make prints of every third frame of the footage. He then traced these prints into his Apple II using an early drawing pad called a VersaWriter.

Chahi’s Amiga allowed a different approach. It had been developed during the brief heyday of laser-disc games in arcades. These often worked by overlaying interactive computer-generated graphics onto static video footage unspooling from the laser disc itself. Wishing to give their new computer the potential to play similar games in the home with the addition of an optional laser-disc player, the designers of the Amiga built into the machine’s graphics chips a way of overlaying the display onto other video; one color of the onscreen palette could be defined as transparent, allowing whatever video lay “below” it to peek through. The imagined laser-disc accessory would never appear due to issues of cost and practicality, but, in a classic example of an unanticipated technological side-effect, this capability combined with the Amiga’s excellent graphics in general made it a wonderful video-production workstation, able to blend digital titles and all sorts of special effects with the analog video sources that still dominated during the era. Indeed, the emerging field of “desktop video” became by far the Amiga’s most sustained and successful niche outside of games.

The same capability now simplified the process of rotoscoping dramatically for Chahi in comparison to what Mechner had been forced to do. He shot video footage of himself on an ordinary camcorder, then played it back on a VCR with single-frame stop capability. To the same television as the VCR was attached his Amiga. Chahi could thus trace the images directly from video into his Amiga, without having to fuss with prints at all.

It wasn’t until months into the development of Another World that a real game, and with it a story of sorts, began to emerge from this primordial soup of graphics technology. Chahi made a lengthy cut scene, rendered, like all of the ones that would follow, using the same graphics engine as the game’s interactive portions for the sake of aesthetic consistency. The entire scene, lasting some two and a half minutes, used just 70 K of disk space thanks to the magic of polygonal graphics. In it, the player’s avatar, a physicist named Lester Cheykin, shows up at his laboratory for a night of research, only to be sucked into his own experiment and literally plunged into another world; he emerges underwater, just a few meters above some vicious plant life eager to make a meal out of him. The player’s first task, then, is to hastily swim to the surface, and the game proper gets underway. The story that follows, such as it is, is one of more desperate escapes from the flora and fauna of this new world, including an intelligent race that don’t like Lester any more than their less intelligent counterparts. Importantly, neither the player nor Lester ever learns precisely where he is — another planet? another dimension? — or why the people that live there — we’ll just call them the “aliens” from now on for simplicity’s sake — want to kill him.

True to the spirit of the kid who found the look of Star Wars more interesting than the plot, the game is constructed with a filmmaker’s eye toward aesthetic composition rather than conventional narrative. After the opening cut scene, the whole game contains not one word devoted to dialog, exposition, or anything else until “The End” appears, excepting only grunts and muffled exclamations made in an alien language you can’t understand. All of Chahi’s efforts were poured into the visual set-pieces, which are consistently striking and surprising, often with multiple layers of action.

Chahi:

I wanted to create a truly immersive game in a very consistent, living universe with a movie feel. I never wanted to create an interactive movie itself. Instead I wanted to extract the essence of a movie — the rhythm and the drama — and place it into game form. To do this I decided to leave the screen free of the usual information aids like an energy bar, score counter, and other icons. Everything had to be in the universe, with no interruptions getting in the way.

Midway through the game, you encounter a friend, an alien who’s been imprisoned — for reasons that, needless to say, are never explained — by the same group who are out to get you. The two of you join forces, helping one another through the rest of the story. Your bond of friendship is masterfully conveyed without using words, relying on the same impressionistic visuals as everything else. The final scene, where the fellow Chahi came to call “Buddy” gently lifts an exhausted Lester onto the back of a strange winged creature and they fly away together, is one of the more transcendent in videogame history, a beautiful closing grace note that leaves you with a lump in your throat. Note the agonizingly slow pace of the snippet below, contrasted with the frenetic pace of the one above. When Chahi speaks about trying to capture the rhythm of a great movie, this is what he means.

For its creator, the ending had another special resonance. When implementing the final scene, two years after retiring into his parents’ basement, Chahi himself felt much like poor exhausted Lester, crawling toward the finish line.

But, you might ask, what has the player spent all of the time between the ominous opening cut scene and the transcendent final one actually doing? In some ways, that’s the least interesting aspect of Another World. The game is at bottom a platforming action-adventure, with a heavy emphasis on the action. Each scene is a challenge to be tackled in two phases: first, you have to figure out what Chahi wants you to do in order to get through its monsters, tricks, and traps; then, you have to execute it all with split-second precision. It’s not particularly easy. The idealized perfect player can make a perfect run through Another World, including watching all of the cut scenes, in half an hour. Imperfect real-world players, on the other hand, can expect to watch Lester die over and over as they slowly blunder their way through the game. At least you’re usually allowed to pick up pretty close to where you left off when Lester dies — because, trust me, he will die, and often.

When we begin to talk of influences and points of comparison for Another World inside the realm of games, one name inevitably leaps to mind first. I already mentioned Jordan Mechner in the context of his own work with rotoscoping, but that’s only the tip of an iceberg of similarities between Another World and his two famous games, Karateka and Prince of Persia. He was another young man with a cinematic eye, more interested in translating the “rhythm and drama” of film to an interactive medium than he was in making “interactive movies” in the sense that his industry at large tended to understand that term. Indeed, Chahi has named Karateka as perhaps the most important ludic influence on Another World, and if anything the parallels between the latter and Prince of Persia are even stronger: both were the virtually single-handed creations of their young auteurs; both largely eschew text in favor of visual storytelling; both clear their screen of score markers and other status indicators in the name of focusing on what’s really important; both are brutally difficult platformers; both can be, because of that brutal difficulty, almost more fun to watch someone else play than they are to play yourself, at least for those of us who aren’t connoisseurs of their try-and-try-again approach to game design.

Still, for all the similarities, nobody is ever likely to mistake Prince of Persia for Another World. Much of the difference must come down to — to engage in yet more crude national stereotyping — the fact that one game is indisputably American, the other very, very French. Mechner, who has vacillated between a career as a game-maker and a filmmaker throughout his life, wrote his movie scripts in the accessible, family-friendly tradition of Steven Spielberg, his favorite director, and brought the same sensibility to his games. But Chahi’s Another World has, as we’ve seen, the sensibility of an art film more so than a blockbuster. The two works together stand as a stark testimony to the way that things which are so superficially similar in art can actually be so dramatically different.

A mentally and physically drained Éric Chahi crawled the final few feet into Delphine’s offices to deliver the finished Another World in late 1991. His final task was to paint the cover art for the box, a last step in the cementing of the game as a deeply personal expression in what was already becoming known as a rather impersonal medium. It was released in Europe before the end of the year, whereupon it became a major, immediate hit for reasons that, truth be told, probably had little to do with its more emotionally resonant qualities: in a market that thrived on novelty, it looked like absolutely nothing else. That alone was enough to drive sales, but in time at least some of the young videogame freaks who purchased it found in it something they’d never bargained for: the ineffable magic of a close encounter with real Art. Memories of those feelings continue to make it a perennial today whenever people of a certain age draw up lists of their favorite games.

Delphine had an established relationship with Interplay as their American publisher. The latter were certainly intrigued by Chahi’s creation, but seemed a little nonplussed by its odd texture. They thus lobbied him for permission to replace its evocative silences, which were only occasionally broken up by Jean-François Freitas’s haunting score, with a more conventional thumping videogame soundtrack. Chahi was decidedly opposed, to the extent of sending Interplay’s offices an “infinite fax” repeating the same sentence again and again: “Keep the original music!” Thankfully, they finally agreed to do so, although conflicts with a long-running daytime soap opera which was also known as Another World did force them to change the name of the game in the United States to the more gung-ho-sounding Out of This World. But on the positive side, they put the game through the rigorous testing process the air-fairy artistes at Delphine couldn’t be bothered with, forcing Chahi to fix hundreds of major and minor bugs and unquestionably turning it into a far tighter, more polished experience.

I remember Out of this World‘s 1992 arrival in the United States with unusual vividness. I was still an Amiga loyalist at the time, even as the platform’s star was all too obviously fading in my country. It will always remain imprinted on my memory as the last “showpiece” Amiga game I encountered, the last time I wanted to call others into the room and tell them to “look at this!” — the last of a long line of such showpieces that had begun with Defender of the Crown back in 1986. For me, then, it marked the end of an era in my life. Shortly thereafter, my once-beloved old Amiga got unceremoniously dumped into the closet, and I didn’t have much to do with computers at all for the next two or three years.

But Interplay, of course, wasn’t thinking of endings when the Amiga version of Out of this World was greeted with warm reviews in the few American magazines still covering Amiga games. Computer Gaming World called the now-iconic introductory cut scene “one of the most imaginative pieces of non-interactive storytelling ever associated with a computer game” — a description which might almost, come to think of it, be applied to the game as a whole, depending on how broad your definition of “interactive storytelling” is willing to be. Reviewers did note that the game was awfully short, however, prompting Interplay to cajole the exhausted Chahi into making one more scene for the much-anticipated MS-DOS port. This he duly did, diluting the concentrated experience that was the original version only moderately in the process.

The game was ported to many more platforms in the years that followed, including to consoles like the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis, eventually even to iOS and Android in the form of a “20th Anniversary Edition.” Chahi estimates that it sold some 1 million copies in all during the 1990s alone. He made the mistake of authorizing Interplay to make a sequel called Heart of the Alien for the Sega CD game console in 1994, albeit with the typically artsy stipulation that it must be told from the point of view of Buddy. The results were so underwhelming that he regrets the decision to this day, and has resisted all further calls to make or authorize sequels. Instead he’s worked on other games over the years, but only intermittently, mixing his work in games with a range of other pursuits such as volcanology, photography, and painting. His ludography remains tiny — another trait, come to think of it, that he shares with Jordan Mechner — and he is still best known by far for Another World, which is perhaps just as well; it’s still his own personal favorite of his games. It remains today a touchstone for a certain school of indie game developers in particular, who continue to find inspiration in its artsy, affective simplicity.

In fact, Another World raises some interesting questions about the very nature of games. Is it possible for a game that’s actually not all that great at all in terms of mechanics and interactivity to nevertheless be a proverbial great game in some more holistic sense? The brilliant strategy-game designer Sid Meier has famously called a good game “a series of interesting decisions.” Another World resoundingly fails to meet this standard of ludic goodness. In it, you the player have virtually no real decisions to make at all; your task is rather to figure out the decisions which Éric Chahi has already made for Lester, and thereby to advance him to the next scene. Of course, the Sid Meier definition of gaming goodness can be used to criticize plenty of other games — even other entire game genres. Certainly most adventure games as well are largely exercises in figuring out the puzzle solutions the author has already set in place. Yet even they generally offer a modicum of flexibility, a certain scope for exploration in, if nothing else, the order in which you approach the puzzles. Another World, on the other hand, allows little more scope for exploration or improvisation than the famously straitjacketed Dragon’s Lair — which is, as it happens, another game Chahi has listed as an inspiration. Winning Dragon’s Lair entails nothing more nor less than making just the right pre-determined motions with the controller at just the right points in the course of watching a static video clip. In Another World, Lester is at least visibly responsive to your commands, but, again, anything but the exactly right commands, executed with perfect precision, just gets him killed and sends you back to the last checkpoint to try again.

So, for all that it’s lovely and moving to look at, does Another World really have any right to be a game at all? Might it not work better as an animated short? Or, to frame the question more positively, what is it about the interactivity of Another World that actually adds to the audiovisual experience? Éric Chahi, for his part, makes a case for his game using a very different criterion from that of Meier’s “interesting decisions”:

It’s true that Another World is difficult. When I played it a year ago, I discovered how frustrating it can be sometimes — and breathtaking at the same time. The trial-and-error doesn’t disturb me, though. Another World is a game of survival on a hostile world, and it really is about life and death. Death doesn’t mean the end of the game, but it is a part of the exploration, a part of the experience. That’s why the death sequences are so diversified. To solve many puzzles, I recognize that you have to die at least once, and this certainly isn’t the philosophy of today’s game design. It is a controversial point in Another World’s design because it truly serves the emotional side of things and the player’s attachment to the characters, but it sometimes has a detrimental effect on the gameplay. Because of this, Another World must be considered first as an intense emotional experience.

Personally, I’m skeptical of whether deliberately frustrating the player, even in the name of artistic affect, is ever a good design strategy, and I must confess that I remain in the camp of players who would rather watch Another World than try to struggle through it on their own. Yet there’s no question that Éric Chahi’s best-remembered game does indeed deserve to be remembered for its rare aesthetic sophistication, and for stimulating emotional responses that go way beyond the typical action-game palette of anger and fear. While there is certainly room for “interesting decisions” in games — and perhaps a few of them might not have gone amiss in Another World itself — games ought to be able to make us feel as well. This lesson of Another World is one every game designer can stand to profit from.

(Sources: the book Principles of Three-Dimension Animation: Modeling, Rendering, and Animating with 3D Computer Graphics by Michael O’Rourke; Computer Gaming World of August 1992; Game Developer of November 2011; Questbusters of June/July 1992; The One of October 1991 and October 1992; Zero of November 1991; Retro Gamer 24 and 158; Amiga Format 1992 annual; bonus materials included with the 20th Anniversary edition of Another World; an interview with Éric Chahi conducted for the film From Bedrooms to Billions: The Amiga Years; Chahi’s postmortem talk about the game at the 2011 Game Developers Conference; “How ‘French Touch’ Gave Early Videogames Art, Brains” from Wired; “The Eccentricities of Eric Chahi” from Eurogamer. The cut-scene and gameplay footage in the article is taken from a World of Longplays YouTube video.

Another World is available for purchase on GOG.com in a 20th Anniversary Edition with lots of bonus content.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | More modern polygonal-graphics implementations do make use of something called splines to allow for curvature, but these weren’t practical to implement using 1980s and early 1990s computers. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Again, the state of the art in modern polygonal graphics is much different today in this area than it was in Another World‘s time. Today textures are mapped on polygonal surfaces to create a more realistic appearance, and scenes are illuminated by light sources that produce realistic shadings and shadows across the whole. But all of this was hopelessly far beyond what Chahi or anyone else of Another World’s era could hope to implement in a game which needed to be interactive and to run at a reasonable speed. |

Casey Nordell

June 15, 2018 at 5:41 pm

Thank you so much for writing about this game, Jimmy.

Infinitron

June 15, 2018 at 6:25 pm

One thing that would be interesting to explore is to what degree Delphine’s Flashback was truly influenced by Another World. There’s a lot of myths about this.

Helm

June 20, 2018 at 4:03 pm

I’ve thought about this a lot, also. It’s evident that Flashback shares more DNA with Prince of Persia, an american game, in terms of scope, ambition and intended gameplay. But its sci-fi aesthetic seems superficially related to that of Another World.

The themes of Flashback are a pastiche of 80s sci-fi and cyberpunk films, from Blade Runner to the Running Man, to Total Recall, etc. American media. The game started out as a Godfather licensed game, somehow. The story goes that they went ahead and made an engine demo and didn’t follow the Godfather’s storyline enough and U.S. Gold (I think it was the money in this situation) was so excited for their tech that they told them ‘just make this, whatever it is, we’ll fund it’. A Godfather game did come out in 1991 after all, published by U.S. Gold. You can kind of see where perhaps Flashback and this game started out from a similar base?

https://youtu.be/sRO_FggTjc8

I think Flashback isn’t really that Out of this World influenced, ultimately. It’s a French game and it has French idiosyncrasies but I think we shouldn’t overstate its Frenchiness, it’s a very american product. Perhaps it seems to me to be so also because I’m Greek. Perhaps it’s the Moebius / Jean Giraud concept art that really helps Flashback elevate its aesthetics from the comparably plebeian sub-sci-fi-b-movie storytelling in the game to something with more enduring style.

Out of this World has a much subtler touch with different priorities, as this amazing article makes the case for. Flashback is more blunt in its ambitions, more realistic but at the same time more committed to its gameplay conventions as abstract structure that can prop up different themes and levels with the same play. Out of this World just changes its gameplay for every set-piece, it doesn’t care about being a narrow game with a deep challenge that you’ll get so much better at just by playing it, it’s very expansive, broad, expressive, and therefore its essence-as-gameplay is more inchoate. Flashback is a very nitty-gritty video-ass video-game compared. Prince of Persia has its Jungian ego/shadow stuff and it’s so amazingly timed, but the meat of the game in the middle is pure puzzle-platforming and action. These two games share much more than Flashback and Another World.

A good way to understand Prince / Another World / Flashback is to consider how you take steps in these games. Compared between each other, and all of them compared to Mario’s physics which is the dominant paradigm for this sort of game to that point.

In Prince of Persia, you move ‘loosely’ upon a gridded, tiled still screen. It is only when you jump, or try to grab a vertical ledge, or are trying to interact with something on a tile in any case that the engine nudges you on centre of the tile you are near for the verb to go through. It seriously autocorrects you. A lot. Anyone that has played PoP gets a sense of this. But because the engine takes input at 15fps increments that means its going to eat a lot of inputs you pressed *now* but intended for when you’re over *the next tile*. The fuzzy granularity of its hybrid platforming solution means that until you get Prince of Persia Sixth Sense you will fall in a lot of pits or jump up to grab ledges that are too far away. It’s not a good feeling and that’s why a lot of people don’t enjoy playing PoP1 and 2.

(This problem could be solved if the game ran at a very high framerate and accepted overriding input)

So, Prince: a combination of per-pixel free platform game movement like Mario but no, actually, you’re on a grid and you either were on the right tile when you pressed up to do that precarious run-jump-ledge-grab, or you weren’t, but the game is going to help you where it can!

Another World: no grid at all. Not for the art, as its not tilesets, not for the character. He has very little inertia, but he does slide on a pixel level, freely. The game only has 2-3 challenging jumps and they’re resolved without checking ‘are you on the very last tile of this platform?’ but instead just by regular timing. The jump’s trajectory is fixed, but the game is not gridded.

Flashback: Nothing like Another World, it instead takes the idea of Prince of Persia and disambiguates this in a way that’s very special to what that game is. I am sure at some point in the offices of Delphine a conversation was had about the autocorrection in PoP and that it feels bad. The solution they game up was to not have a hybrid movement system at all. In a way Flashback is a more ‘grrr I am a hardcore videogame’ kind of thing. It says ‘no, we are on grid. Everything is on grid. Every tile is on a grid and the character is on a grid for every action. When you press a button, you will move exactly one tile over.’ This is very core to the formalist ambitions of Flashback because then the different levels and their gimmicks are just different tilesets, all operating under the exact same puzzle-platformer tile-snapped engine. You put in the same inputs for the same verbs exactly throughout Flashback.

Compare to a scene in Another World where you are caught by a native guard (you’re really the alien) and as you’re held by the collar, mid-air you’re supposed to input ‘kick guard in the nuts’ then run towards your gun on the ground, roll to pick it up, turn mid-roll towards the guard and zap him.

None of this fever dream of a sequence is supported by the gameplay of Another World up to that point. And Chahi is crazy and talented enough that he just went and did it. Play that sequence in Another World when you have the time. The keypresses you input are

action button = kick in nads

press left as you’re released = Lester runs towards his gun

press down when you’re near the gun = Lester automatically rolls to the ground to pick up the gun. You have never made him roll before in this way

press action button = you zap the guard before he recovers from the kick in the nads.

It’s insane that it works as well it does. The same scenario in Flashback would not be bespoke code, it would be here’s a tile with your gun on it, here’s you many tiles away, here’s two guards that will kill you unless you use all your game verbs and corresponding iframes to reach your gun, pick it up, equip it, shoot the guards. I don’t have to imagine this, as this sequence happens like that in Flashback on the prison level. They obviously looked at Another World’s ‘captured without a gun’ sequence and wanted to do their version of it. And their version uses the exact same engine tools that the rest of their game uses.

This dedication to the formalism of the engine makes Flashback a more ‘real’ experience. Another World is a more dreamlike impression, even though it’s hard as nails, every little bit of it is hard in its special way, without an overarching system. It’s a different approach to game design completely. Bespoke versus formalist.

Think of how difficult it is to add more levels to Another World in your mind, whereas Flashback can be easily expanded with more graphics and a few more gimmicks. I love the game, but it does show the signs of a completely different level of ambition and self-understanding as a videogame compared to Another World. The latter is kind of punk rock compared to the universal solution to movement that Flashback settled on.

These tensions are still alive in modern videogame culture. Flashback won a phyrric victory insofar that Prince of Persia won the historical lottery as the cinematic platformer UR-text. Play the first Tomb Raider. It works exactly like Prince of Persia 1 works (fuzzy per-pixel movement over a tile engine with grace code to nudge you in place if you were close enough) but in 3d. Most modern cinematic action games on modern consoles use these concepts and build on them liberally: giving you a gameplay structure that can support a lot of different locales, milieus and assets but plays in this loose way. Show you a nice setpiece, then you kind of blunder through with an ok jump from ledge to ledge and the game helps you cross the distance, yay you did a cool thing on screen. Autotarget for easier headshots, yay, you look so cool.

Flashback is similar but wouldn’t work like this in 3D and we know this because we got “Fade to Black”. That game failed because Flashback’s 2D controls over a gridded plane did not translate well with the compromises they made to make in 3D. Stiff, unresponsive, like you’re playing in a sci-fi action movie and you’re nursing a two day hangover.

Peter Smith

June 22, 2018 at 1:07 pm

This is a great analysis!

Ola Hansson

June 23, 2018 at 1:26 am

Very illuminating comment, thanks!

Lisa H.

June 15, 2018 at 7:51 pm

That opening scene is really something. I’m into it. Certainly does the job of evoking tension. But if the video with all the gunfire is typical of the gameplay, I would be quitting in two seconds flat. I’d never manage it.

If it’s not too much of a spoiler, what’s happened to Lester’s legs in the last video? I assume some kind of serious injury (not just exhaustion, or they’d have animated a different crawl)?

Jimmy Maher

June 15, 2018 at 8:08 pm

It’s not all shooting. You don’t even get a gun until nearly halfway through the game. But when it’s not shooting, it’s running and pinpoint jumping, which isn’t really any easier. While you could make an argument, as Chahi kind of does, about all of the death and repetition reinforcing your connection with Lester and his plight, yada yada, the actual gameplay remains the least interesting aspect of the game for me.

Lester takes a beating from one of the evil guys just before that scene, but it’s not clear what the exact nature of his injuries are. You can watch the whole thing from beginning to end at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTrQz3o_HiA, if you like. Only 25 minutes long. ;)

Lisa H.

June 19, 2018 at 9:48 pm

Yeah, that doesn’t look like it would be my cuppa.

Eriorg

June 15, 2018 at 9:53 pm

Thank you for this very interesting article!

In the late 1980s/early 1990s, I used to play games on the Amstrad CPC and I lived in France (I’m French and Swiss). Captain Blood was actually my favorite game. I played many French games and even more British ones (but very few American ones, because not that many were available on the Amstrad). But at the time, I never noticed that French games (or foreign games, for that matter) were weirder than the others, or even particulary different from them! It’s only much later, on the Internet, that I learned that non-French people often had that feeling, apparently.

So, if there are any French people here who used to play computer games in the 1980s/1990s, I’d like to ask them: did you feel that French games were different?

I also have a question for Jimmy: what do you mean exactly by “the long-established French ambivalence toward translation from their mother tongue”?

Jimmy Maher

June 16, 2018 at 6:17 am

My impression is that a certain… shall we say, chauvinism still surrounds the French language among many native speakers. There’s a pretty good reason for that: it’s certainly the most lovely spoken language I’ve ever heard. If you can speak in a language like that, why would you want to use any other? And of course there may persist a certain sting at French having been displaced by English as the world’s language at some point in the nineteenth century. I think all this tends to create the grumbling reluctance to translate into English which I’ve read of in various places. It gets done, of course… just a little grudgingly. ;) Probably an older-generation thing anyway. When I was in Paris last year, I was surprised at how much more willing people — especially young people — were to speak English to this poor non-Francophone than they were the last time I was there, all the way back in 1998.

My, I am stereotyping today, aren’t I? ;)

Bastien

June 16, 2018 at 7:39 am

Nice article, and great sensations watching those videos!

I’m french, I started playing video games with the Amstrad CPC 464 (Manic Miner, anyone?) and I continued with the Atari 520 ST, also with Captain Blood as one of my favorites (the J.-M. Jarre intro music was just too good.)

At the time, I was too young to wonder what country the game was born in and I didn’t notice anything different about french games.

Impressionism is born in France but I’m not sure it means that french artworks, including video games, are more likely to be influenced by this movement than, say, american artworks.

To me, it’s more like this: some french artists invent new styles, including this “cinematic” style in video games, then anything vaguely related to this style is aggregated into the “so french” stereotype, with its precise definition blurred. But this would lead to complex aesthetic discussions that I cannot start on a saturday morning, drinking coffee in the kitchen :)

Jimmy Maher

June 16, 2018 at 8:37 am

An important factor here may be that the more derivative, less unique French games didn’t tend to get exported to English-speaking countries — because why would you want to really? They’re just average games that come with the additional burden of translation. The more aesthetically or thematically ambitious stuff, on the other hand, could be attractive for export because of its uniqueness. This could create a skewed view of French gaming culture for someone who views it only from the outside.

Pedro Timóteo

June 16, 2018 at 10:00 am

I remember British ZX Spectrum magazines, especially Your Sinclair, constantly mentioning how weird French games were — even though they typically gave them good ratings. :)

I’d really have liked to read a full post by Jimmy about Captain Blood (still one of both the weirdest and most intriguing games I’ve ever seen, although the gameplay itself isn’t that great, IMO), but I guess we’re past that time, and the paragraph in this post is all we’ll get, right?

Jimmy Maher

June 17, 2018 at 7:27 am

Yeah, I don’t think I’ll have much more to say about that one. I have a bias toward designers that do the hard, unexciting work of balancing their games for playability and solubility. Unfortunately, the French Touch could cut both ways.

Jacen

June 16, 2018 at 4:40 am

“This illustrations shows how”

Jimmy Maher

June 16, 2018 at 6:09 am

Thanks!

Laundro

June 16, 2018 at 7:53 am

I was about 12 when I played Another World on my Amiga. It’s the only game that has ever made me cry… (The end scene did that).

Mike Taylor

November 20, 2018 at 2:03 am

The ending of BioShock did it go me. Just lovely.

Mark

August 21, 2022 at 12:04 pm

Well, me too, I must admit :)

don bright

June 16, 2018 at 5:39 pm

Thanks. As a kid i couldnt possibly have imagined what was going on behind this games creation. All i knew was there was something fascinating about it. Back before internet you really sat and experienced a game because there were so few distractions. The movements were so fluid.. Like nothing else. It was like magic. I dont remember finishing it until later in life though. Hard to translate that experience to modern times. Loving a game without being capable of finishing it. Without streaming or multiplayer. Without a score online forums to read about it. Thanks.

Steven Marsh

June 16, 2018 at 6:28 pm

Interesting article! I think Another World is one of those games I’ve owned on at least three different platforms, and never gotten very far in any of them for obvious reasons.

“an extensional quest for identity” — Should that be “an existential quest…”?

Jimmy Maher

June 16, 2018 at 10:26 pm

Indeed. Thanks!

Peter Ferrie

June 16, 2018 at 7:24 pm

Thank you Jimmy for the wonderful article that brings back memories of one of my favourite games.

I’m in that age-range, of course.

French Touch is also the name of a recent demo-maker for the Apple II scene, producing some of the most interesting effects ever seen on the hardware (and exposing the enormous gaps in the fidelity of modern emulators).

Alexander King

June 16, 2018 at 7:29 pm

This stood out to me. Freedom: Rebels in the Darkness is a little bit odd to use to showcase ‘French strangeness’, since while it’s a French published game, it was made by Martinican designer Muriel Tramis. Which is also where the game takes place, so “slave on a French colonial plantation” might be more accurate than ‘antebellum’, which suggests the American south. It’s an atypical game even in the context of French games.

It also feels like a bit of a slight to call such a unique work from one of the few Afro-Caribbean women game designers “deeply, deeply strange stuff” (even from an American kid’s perspective). It appears contemporary reviews treated it with the respect and gravity you’d expect given the subject matter, not as some strange game. Phil Salvador over at the Obscuritory has a great piece about the game, and recently interviewed Muriel Tramis as well.

Jimmy Maher

June 16, 2018 at 10:23 pm

No slight was intended nor, I would argue, implied, given that the “deep strangeness” is clearly seen from the perspective of teenage American gamers — not exactly the most sophisticated audience. That said, it’s perhaps not the best example to use in that paragraph about French games reflecting American culture back on itself, given that it deals with French colonial history. Was going on only memories of that one, which sometimes gets me into trouble. I’ve cut the mention. Thanks!

Rowan Lipkovits

June 19, 2018 at 4:49 pm

The career of Muriel at Coktel might be well worthwhile as a post subject, the increasingly improbable sum of her game industry outsider identities (French, woman, Afro-Caribbean) culminating in someone making games it would never occur to anyone else to make — and the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of someone in that situation somehow receiving a green light to be funded in these uncharted explorations.

In addition to the Obscuritory interview, she also spoke at length with The Adventure Gamer a little while ago. It almost seems like she was 25 years ahead of her time.

Jimmy Maher

June 20, 2018 at 8:17 am

My only reluctance stems from my opinion that most of her actual games just aren’t very well-designed at all. I’m afraid she thus justifies her reputation as “the Roberta Williams of France” a little bit too well. ;)

Casey Muratori

June 17, 2018 at 8:43 am

I think perhaps “the individuals polygons” should be “individual” (not plural).

– Casey

Jimmy Maher

June 17, 2018 at 9:06 am

Thanks!

Poddy

June 17, 2018 at 11:06 pm

The only French game I can recall playing from more-or-less that era was called “Robinson’s Requiem”. In theory, it was a fantastically open-world game where your one goal, escape, takes you all over the planet and requires you to monitor and create food, health supplies, weapons and endless exciting resources. In practice, it was fantastically unforgiving and any choice in your pace, direction, or crafting could be what killed you. It still fascinates me, and it does have a lot of… atmosphere, although not nearly as much as “Another World”. Death was everywhere and terrifying, and an attractive woman beckoned you to safety in your dreams.

Jimmy Maher

June 18, 2018 at 9:27 am

Yes, that’s a classic example of the French Touch in gaming: wonderfully original themes and gameplay concepts, brilliant aesthetics, all undone by an apparent unwillingness to put in the hard work required to turn it all into a genuinely great game. This wasn’t always the case — Dune is decent, Alone in the Dark is a true classic, and I’m sure there are other counterexamples — but it held true more often than one might wish.

Gnoman

June 20, 2018 at 1:10 am

Since you mention it as a “true classic”, I’m curious. Do you plan to spend much time going down the “survival horror” rabbit hole that really gets started (despite some even earlier precursors you’ve mentioned recently) with Alone in the Dark? I realize that this isn’t exactly your territory (particularly since the sub-genre really got going with the console-exclusive (at least for the first game) Silent Hill and the primarily console Resident Evil games, and you’ve said before that consoles aren’t something you spent much time with), but I’ve always viewed this genre as one of the obvious evolutions of classic adventure games, and would be rather interested to hear your thoughts on the matter.

Jimmy Maher

June 20, 2018 at 7:57 am

It’s a genre I find intrinsically interesting for the way it upends the typical power-fantasy narrative, but I confess that I’m not super-familiar with its history and progression. We’ll just have to start with Alone in the Dark and see how we go. ;)

Chris D

June 18, 2018 at 1:16 pm

French games were definitely stereotyped as being unbelievably weird and kooky in the UK games press of the eighties and nineties, but in retrospect I’m not sure they were particularly stranger than British games of that era. Captain Blood, Purple Saturn Day, and (especially) Kult were very strange games, and any review or preview of a French game in a British mag was contractually obliged to stress how bonkers the game and its programmers were, but I’m not sure they were any weirder than, say, Jeff Minter’s output, or Fat Worm Blows a Sparky, or Deus Ex Machina, or Wiz Kid, or Knights of the Crystallion, or any number of other examples of borderline outsider art that came out of UK developers during the 8/16-bit period (with Knights of the Crystallion showing that American developers could be pretty flipping weird if they put the hours in). I guess that from a British perspective, British programmers were bonkers in an accessible, familiar way, whereas French programmers were bonkers in a weird, frightening way, in the same way that surly teenagers seem inexplicably threatening when they’re French exchange students.

I suspect that French games may have acquired a reputation for weirdness through poor translation, slightly more formal innovation, and a more liberal attitude to sex & nudity – on the latter point, look at the original box art for Ranxerox, or the way that the ‘disco dancing’ mini-game in B.A.T. originally involved you waggling the joystick to have sex (supposedly – I can’t find much evidence that this was actually the case, and I suspect it might just be an urban myth lent plausibility by the crazy Frenchman stereotype).

Helm

June 20, 2018 at 4:18 pm

I’m Greek and born in 1984 and I played all these things as they came out and at the time I didn’t think French games in particular were weirder than those of other European devs. There was a difference between European titles, American titles and especially Japanese titles for younger me for sure, but the biggest difference in the west always was on whether the game was made by one or two people, or a full studio.

Greece was in the US sphere of influence during the cold war, but there was a strong Soviet cultural counterpoint to this, up to a point, and relative to what sort of family one grew up in. We would watch Robocop and the Seventh Seal next to each other and we would think all of this was cinema and he somehow had to reconcile them. It’s a very specific vantage.

I do think this over-emphasis on the French Touch is a half invention of the gaming press at the time. It’s perhaps because of French new wave cinema? Honestly if you look at Chambers of the Sci-Mutant Priestess and you say ‘that’s so weird’ then I look at Monty on the Run and I think that’s just as weird. The 8-bit scene in Europe and even moreso with the Amiga was all weird, but not because of Frenchiness but because these were games made by bedroom coders, real humans growing up in a strange world.

American games from bigger companies always made more sense, for what sense is worth.

Joe

June 18, 2018 at 10:20 pm

Although you mention “Future Wars”, you did not mention the two adventure games that immediately followed from Delphine “Operation: Stealth” and “Cruise for a Corpse”. Neither of them are very good.

“Operation: Stealth” is about as stereotypical of a Sierra-style adventure as you could get, with its only redeeming quality that it was not a bad James Bond game in the countries that published it as that. (Elsewhere in the world, it was a more generic spy but the Bond influences are pretty clear.)

“Cruise for a Corpse” is a locked-room mystery about people gathered together for a family cruise only to be knocked off one-by-one. It has a good plot, but is absolutely terrible mainly due to the need to search every individual drawer, shelf, and location over and over and over again to advance the plot. You’ve searched the laundry bins individually thirty times before? Well, keep searching because something will appear in one at one point in the game and you never know when. (Repeat for just about every clue you find only appearing at the exact right moment.)

Although these games were Delphine games, I do not believe that Chahi had much if any influence on them. Which is perhaps more the shame.

Helm

June 20, 2018 at 4:19 pm

Future Wars has absolutely terrible puzzles too.

Lt. Nitpicker

June 20, 2018 at 4:22 pm

Heart of the Alien was developed by Interplay and was published by Virgin Interactive, not Sega, as stated by many places, including Chahi’s own website for Another World.

Jimmy Maher

June 22, 2018 at 2:54 pm

Thanks!

Olof Kindgren

June 21, 2018 at 11:00 am

I intended to write that you wrote draftsman instead of craftsman, but as I looked up the former word I’m not sure anymore. Seems to have plenty of different meanings :)

Anyway, very interesting article. I remember everyone was really impressed by Another world, even though I was more into Flashback myself, which I was convinced was basically a sequel until reading some of the comments on this article.

Also found the note about North & South, which I loved as a kid, interesting. It has always seemed like a very American game to me, particularly with the cartoon slapstick aesthetics. Had no idea it was French

Eriorg

June 21, 2018 at 6:17 pm

To be more precise, North & South was a French adaptation of a Belgian comics series.

Alex Freeman

June 22, 2018 at 5:36 am

But what about the textures that are put on the polygons? Those are typically bitmaps.

I’d say that quote does a good job of summing up why Another World succeeds much more from a narrative perspective than the full-motion video games that followed it did.

Speaking of which, this and your article on The Incredible Machine has made me wonder if the way forward with adventure games is to have the games be really short or consist of self-contained short arcs that can easily be completed in one sitting or be at least easy to resume if one can’t complete it in one sitting. That way it would combine the qualities of casual games like TIM and Lemmings with the narrative structure of Another World and Dragon’s Lair.

Jimmy Maher

June 22, 2018 at 7:09 am

Textures weren’t yet used during this era. Just managing to fill the polygons with solid blocks of color, as opposed to leaving them as wireframes, counted as progress on many fronts. ;)

The direction you describe is in fact the direction that text adventures have largely gone. The influence of the IF Comp has led to a huge prevalence of snack-size games completeable in two hours or less. Bigger games have long since become the anomalies.

There are also a lot “casual adventure games” sold on portals like Big Fish. Unfortunately, they’re usually pretty rote, uninspired exercises — like most of the stuff on Big Fish, come to think of it. It’s a shame the casual market hasn’t done better by its players.

Lt. Nitpicker

June 22, 2018 at 2:43 pm

It’s worth noting that while textures were very rare to see in real-time 3D, it was a common technique in non-real time uses around this time.

Alex Freeman

June 22, 2018 at 3:55 pm

Well, I was thinking of adventure games (or adventure games arcs at least) even shorter than two hours. Such as something a typical player could complete in 20 minutes, and it would have only have no more than, say, five rooms, so keeping a mental map would be easy. Well, maybe when I’ve honed my craft a bit more, I’ll give it a try.

Alan Twelve

June 23, 2018 at 10:00 pm

Nice piece, Jimmy, and you can certainly include me among those who’d rather watch this being played than actually play it – I’ve tried many times but can hardly even get started!

Some possible corrections:

“the emotional affect of the whole.”

“creating an affect that’s difficult to put into words”

“even in the name of artistic affect”

These should all read “effect,” and not “affect,” I think (affect being a verb and not a noun). I suspect this should too, but maybe not:

“artsy, affective simplicity.”

Also:

“using a very different criteria ”

Should either read as “using very different criteria,” or “using a very different criterion.”

Jimmy Maher

June 24, 2018 at 8:56 am

“Affect” actually has a meaning of its own when used as a noun, so the usage was intentional.

But you got me on the last point. ;) Thanks!

Alex Freeman

June 26, 2018 at 5:48 am

Come to think of it, though, since “affect” as a noun means, “specific emotional response”, wouldn’t “emotional affect” be redundant?

Jimmy Maher

June 26, 2018 at 7:19 am

Literally, yes. But it’s not as common a word as “effect” and I wanted to emphasize the point I was making in using it.

Mark Papadakis

June 24, 2018 at 7:41 pm

I too didn’t consider all those games developed in French as particularly weird, certainty no more weird than games produced elsewhere, as my fellow Greek suggested in an earlier comment. Most of those games tough have a distinctive French style, which mostly comes down to the aesthetics and visuals, but not necessarily only specific to that.

The French game that I enjoyed the most and still remember fondly to this day is Lankhor’s Maupiti Island. It’s very difficult to progress through the game but it looks and sounds fantastic ( and it is perhaps one of first games to make extensive use of the Amiga speech synthesis abilities ). The intro screen tune is also excellent. I highly recommend it.

jalapeno_dude

June 25, 2018 at 9:20 pm

I couldn’t help but notice that the code entered on the keypad in the opening cutscene starts with 451–any idea on whether this had an influence on the famous use of 0451 in System Shock/Deus Ex/etc., and/or if it was a homage to Fahrenheit 451?

David Boddie

July 3, 2018 at 3:38 pm

I happened upon this code review and overview of the technology behind the game: “Another World” Code Review. It links through to the Eric Chahi’s own site.

It’s interesting to see how graphical adventures embraced the technology of the virtual machine just as text adventures had before them, but that action games at the time were still (I’m guessing) built using more traditional techniques.

Sion Fiction

December 28, 2024 at 12:35 am

Fabiens code reviews are awesome. He’s also written 3 great Technical Breakdown books on DOOM, Wolfenstein 3D & Capcoms CP System that powers Street Fighter II. I hope he does Quake one day!

Kenny

July 12, 2018 at 9:05 pm

I’ve always loved the look of this game but I don’t remember now where exactly I saw it first. Probably one of the console ports. I certainly never finished it back when it was new. I may have never really played it for more than a few minutes!

I did tho pick it up somewhat recently when I discovered an iOS (iPhone and iPad) port had been published. It’s still hard, and I ended-up looking-up the solution to one or two of the ‘puzzles’, but I think it might be a lot easier still on a device with a touch screen.

Wolfeye M.

October 18, 2019 at 3:35 am

After many frustrating encounters with various video games, I decided that it doesn’t matter how pretty a game is, if it isn’t fun to play. Another World doesn’t sound fun to play at all. The only intense emotion I’d feel is frustration that the game is so badly designed, despite looking so cool. That said, I might just look up a playthrough of the game on YouTube, so I can watch the story play out, without having to deal with the horrible game mechanics myself.

Bog

January 10, 2020 at 7:04 pm

Jimmy, I’ve been reading your blog for quite some time (some 2 years or so) but, as far as I can remember, this is the first time I am commenting. I must say that it became my favorite blog, though I am still playing catch-up.

I would just like to emphasize that, although it uses polygonal graphics, Another World approach is very different from what was found on, for example, racing and flying sims. It doesn’t have a fully realized 3D environment, so there is no way to position a “camera”. Even the objects are not 3D models. Instead, these are just 2D polygons whose vertices are moved around the 2D image plane.

On the one hand, that means much of the flexibility allowed by 3D engines, especially regarding camera positioning, was not available to Chahi. On the other hand, that means his engine doesn’t have to perform all the processor-intensive geometry needed to project the 3D scene into the 2D image plane. This also allowed his game to use rotoscoping, and to run at much higher frame rates than your usual flight sim of the era. The end result can also benefit from interpolating vertex positions between keypoints, resulting in very, very, smooth movement, with a very low memory budget and modest processor load. A very unique approach indeed.

Saul Ansbacher

January 22, 2020 at 7:34 pm

Similar to David Boddie’s post, Fabien Sanglard has released a series of Another World reviews based on the polygon engine on different platforms, the first one is here: http://fabiensanglard.net/another_world_polygons/index.html

But then see the whole list here, near the top of his Blog posts:

http://fabiensanglard.net/

Covering Amiga, Atari ST, PC, Genesis, and SNES so far. Interesting reads if you lke more technical info.

-Saul

PS: Love the blog, thanks so much!

Ben

May 16, 2025 at 9:22 pm

postmorten -> postmortem

Jimmy Maher

May 20, 2025 at 6:29 am

Thanks!