Act 1: Starcraft the Game

Great success brings with it great expectations. And sometimes it brings an identity crisis as well.

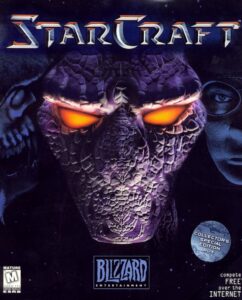

After Blizzard Entertainment’s Warcraft: Orcs and Humans became a hit in 1995, the company started down a very conventional path for a new publisher feeling its oats, initiating a diverse array of projects from internal and external development teams. In addition to the inevitable Warcraft sequel, there were a streamlined CRPG known as Diablo, a turn-based tactical-battle game known as Shattered Nations, a 4X grand-strategy game known as Pax Imperia II, even an adventure game taking place in the Warcraft universe — to be called, naturally enough, Warcraft Adventures. Then, too, even before Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness was finished, Blizzard had already started on a different sort of spinoff than Warcraft Adventures, one which jettisoned the fantasy universe but stayed within the same gameplay genre of real-time strategy. It was to be called Starcraft, and was to replace fantasy with science fiction. Blizzard thought that one team could crank it out fairly quickly using the existing Warcraft II engine, while another one retooled their core RTS technology for Warcraft III.

In May of 1996, with Warcraft II now six months old and a massive hit, Blizzard brought early demos of Starcraft and most of their other works in progress to E3, the games industry’s new annual showcase. One could make a strong argument that the next few days on the E3 show floor were the defining instant for the Blizzard brand as we still know it today.

The version of Starcraft that Blizzard brought to the 1996 E3 show. Journalists made fun of its fluorescent purple color palette among other things. Was this game being designed by Prince?

The gaming press was not particularly kind to the hodgepodge of products that Blizzard showed them at E3. They were especially cruel to Starcraft, which they roundly mocked for being exactly what it was, a thinly reskinned version of Warcraft II — or, as some journalists took to calling it, Orcs in Space. Everyone from Blizzard came home badly shaken by the treatment. So, after a period of soul searching and much fraught internal discussion, Blizzard’s co-founders Allen Adham and Mike Morhaime decided not to be quite so conventional in the way they ran their business. They took a machete to their jungle of projects which seemed to have spontaneously sprouted out of nowhere as soon as the money started to roll in. When all was said and done, they allowed only two of them to live on: Diablo, which was being developed at the newly established Blizzard North, of San Mateo, California; and Starcraft, down at Blizzard South in Irvine, California. But the latter was no longer to be just a spinoff. “We realized, this product’s just going to suck,” says Blizzard programmer Pat Wyatt of the state of the game at that time. “We need to have all our effort put into it. And everything about it was rebooted: the team that was working on it, the leadership, the design, the artwork — everything was changed.”

Blizzard’s new modus operandi would be to publish relatively few games, but to make sure that each and every one of them was awesome, no matter what it took. In pursuit of that goal, they would do almost everything in-house, and they would release no game before its time. The time of Starcraft, that erstwhile quickie Warcraft spinoff, wouldn’t come until March of 1998, while Warcraft III wouldn’t drop until 2002. In defiance of all of the industry’s conventional wisdom, the long gaps between releases wouldn’t prove ruinous; quite the opposite, in fact. Make the games awesome, Blizzard would learn, and the gamers will be there waiting with money in hand when they finally make their appearance.

Adham and Morhaime fostered as non-hierarchical a structure as possible at Blizzard, such that everyone, regardless of their ostensible role — from programmers to artists, testers to marketers — felt empowered to make design suggestions, knowing that they would be acted upon if they were judged worthy by their peers. Thus, although James Phinney and Chris Metzen were credited as “lead designers” on Starcraft, the more telling credit is the one that attributes the design as a whole simply to “Blizzard Entertainment.” The founders preferred to promote from within, retaining the entry-level employees who had grown up with the Blizzard Way rather than trying to acclimatize outsiders who were used to less freewheeling approaches. Phinney and Metzen were typical examples: the former had started at Blizzard as a humble tester, the latter as a manual writer and line artist.

For all that Blizzard’s ambitions for Starcraft increased dramatically over the course of its development, it was never intended to be a radical formal departure from what had come before. From start to finish, it was nothing more nor less than another sprite-based 2D RTS like Warcraft II. It was just to be a better iteration on that concept — so much better that it verged on becoming a sort of Platonic ideal for this style of game. Blizzard would keep on improving it until they started to run out of ideas for making it better still. Only then would they think about shipping it.

The exceptions to this rule of iteration rather than blue-sky invention all surrounded the factions that you could either control or play against. There were three of them rather than the standard two, for one thing. But far more importantly, each of the factions was truly unique, in marked contrast to those of Warcraft and Warcraft II. In those games, the two factions’ units largely mirrored one another in a tit-for-tat fashion, merely substituting different names and sprites for the same sets of core functions. Yet Starcraft had what Blizzard liked to call an “asymmetric” design; each of the three factions played dramatically differently, with none of the neat one-to-one correspondences that had been the norm within the RTS genre prior to this point.

In fact, the factions could hardly have been more different from one another. There were the Terrans, Marines in space who talked like the drill sergeant in Full Metal Jacket and fought with rifles and tanks made out of good old reliable steel; the Zerg, an insectoid alien race in thrall to a central hive mind, all crunchy carapaces and savage slime; and the Protoss, aloof, enigmatic giants who could employ psionic powers as devastatingly as they could their ultra-high-tech weaponry.

The single-player campaign in which you got to take the factions for a spin was innovative in its way as well. Instead of asking you to choose a side to control at the outset, the campaign expected you to play all three of them in succession, working your way through a sprawling story of interstellar conflict, as told in no fewer than 30 individual scenarios. It cleverly began by placing you in control of the Terrans, the most immediately relatable faction, then moved on to the movie-monster-like Zerg and finally the profoundly alien Protoss once you’d gotten your sea legs.

Although it seems safe to say that the campaign was never the most exciting part of Starcraft for the hyper-competitive young men at Blizzard, they didn’t stint on the effort they put into it. They recognized that the story and cinematics of Westwood Studio’s Command & Conquer — all that stuff around the game proper — was the one area where that arch-rival RTS franchise had comprehensively outdone them to date. Determined to rectify this, they hired Harley D. Huggins II, a fellow who had done some CGI production on the recent film Starship Troopers — a movie whose overall aesthetic had more than a little in common with Starcraft — as the leader of their first dedicated cinematics team. The story can be a bit hard to follow, what with its sometimes baffling tangle of groups who are forever allying with and then betraying one another, the better to set up every possible permutation of battle. (As Blizzard wrote on their back-of-the-box copy, “The only allies are enemies!”) Still, no one can deny that the campaign is presented really, really well, from the cut-scenes that come along every few scenarios to the voice acting during the mission briefings, which turn into little audio dramas in themselves. That said, a surprising amount of the story is actually conveyed during the missions, when your objectives can unexpectedly change on a dime; this was new to the RTS genre.

One of the cut-scenes which pop up every few scenarios during the campaign. Blizzard’s guiding ethic was to make them striking but short, such that no one would be tempted to skip them. Their core player demographic was not known for its patience with long-winded exposition…

Nonetheless, any hardcore Starcraft player will tell you that multiplayer is where it’s really at. When Blizzard released Diablo in the dying days of 1996, they debuted alongside it Battle.net, a social space and matchmaking service for multiplayer sessions over the Internet. Its contribution to Diablo’s enormous success is incalculable. Starcraft was to be the second game supported by the service, and Blizzard had no reason to doubt that it would prove just as important if not more so to their latest RTS.

If all of Starcraft was to be awesome, multiplayer Starcraft had to be the most awesome part of all. This meant that the factions had to be balanced; it wouldn’t do to have the outcome of matches decided before they even began, based simply upon who was playing as whom. After the basic framework of the game was in place, Blizzard brought in a rare outsider, a tireless analytical mind by the name of Rob Pardo, to be a sort of balance specialist, looking endlessly for ways to break the game. He not only played it to exhaustion himself but watched match after match, including hundreds played over Battle.net by fans who were lucky enough to be allowed to join a special beta program, the forerunner of Steam Early Access and the like of today. Rather than merely erasing the affordances that led to balance problems — affordances which were often among the funnest parts of the game — Pardo preferred to tweak the numbers involved and/or to implement possible countermeasures for the other factions, then throw the game out for yet another round of testing. This process added months to the development cycle, but no one seemed to mind. “We will release it when it’s ready,” remained Blizzard’s credo, in defiance of holidays, fiscal quarters, and all of the other everyday business logic of their industry. Luckily, the ongoing strong sales of Warcraft II and Diablo gave them that luxury.

Indeed, Blizzard veterans like to joke today that Starcraft was just two months away from release for a good fourteen months. They crunched and crunched and crunched, living lifestyles that were the opposite of healthy. “Relationships were destroyed,” admits Pat Wyatt. “People got sick.” At last, on March 27, 1998, the exhausted team pronounced the game done and sent it off to be pressed onto hundreds of thousands of CDs. The first boxed copies reached store shelves four days later.

Starcraft was a superb game by any standard, the most tactically intricate, balanced, and polished RTS to date, arguably for years still to come. It was familiar enough not to intimidate, yet fresh enough to make the purchase amply justifiable. Thanks to all of these qualities, it sold more than 1.5 million copies in the first nine months, becoming the biggest new computer game of the year. By the end of 1998, Battle.net was hosting more than 100,000 concurrent users during peak hours. Blizzard was now the hottest name in computer gaming; they had left even id Software — not to mention Westwood of Command & Conquer fame — in their dust.

There was always a snowball effect when it came to online games in particular; everyone wanted the game their friends were already playing, so that they too could get in on the communal fun. Thus Starcraft continued to sell well for years and years, flirting with 10 million units worldwide before all was said and done, by which time it had become almost synonymous with the RTS in general for many gamers. Although your conclusions can vary depending on where you move the goalposts — Myst sold more units during the 1990s — Starcraft has at the very least a reasonable claim to the title of most successful single computer game of its decade. Everyone who played games during its pre- and post-millennial heyday, everyone who had a friend that did so, everyone who even had a friend of a friend that did so remembers Starcraft today. It became that inescapable. And yet the Starcraft mania in the West was nothing compared to the fanaticism it engendered in one mid-sized Asian country.

If you had told the folks at Blizzard on the day they shipped Starcraft that their game would soon be played for significant money by professional teams of young people who trained as hard or harder than traditional athletes, they would have been shocked. If you had told them that these digital gladiators would still be playing it fifteen years later, they wouldn’t have believed you. And if you had told them that all of this would be happening in, of all places, South Korea, they would have decided you were as crazy as a bug in a rug. But all of these things would come to pass.

Act 2: Starcraft and the Rise of Gaming as a Spectator Sport

Why Starcraft? And why South Korea?

We’ve gone a long way toward answering the first question already. More than any RTS that came before it and the vast majority of those that came after it, Starcraft lent itself to esport competition by being so incredibly well-balanced. Terran, Zerg, or Protoss… you could win (and lose) with any of them. The game was subtle and complex enough that viable new strategies would still be appearing a decade after its release. At the same time, though, it was immediately comprehensible in the broad strokes and fast-paced enough to be a viable spectator sport, with most matches between experienced players wrapping up within half an hour. A typical Command & Conquer or Age of Empires match lasted about twice as long, with far more downtime when little was happening in the way of onscreen excitement.

The question of why South Korea is more complicated to answer, but by no means impossible. In the three decades up to the mid-1990s, the country’s economy expanded like gangbusters. Its gross national product increased by an average of 8.2 percent annually, with average annual household income increasing from $80 to over $10,000 over that span. In 1997, however, all of that came to a crashing halt for the time being, when an overenthusiastic and under-regulated banking sector collapsed like a house of cards, resulting in the worst recession in the country’s modern history. The International Monetary Fund had to step in to prevent a full-scale societal collapse, an intervention which South Koreans universally regarded as a profound national humiliation.

This might not seem like an environment overly conducive to a new fad in pop culture, but it proved to be exactly that. The economic crash left a lot of laid-off businessmen — in South Korea during this era, they were always men — looking for ways to make ends meet. With the banking system in free fall, there was no chance of securing much in the way of financing. So, instead of thinking on a national or global scale, as they had been used to doing, they thought about what they could do close to home. Some opened fried-chicken joints or bought themselves a taxicab. Others, however, turned to Internet cafés — or “PC bangs,” as they were called in the local lingo.

Prior to the economic crisis, the South Korean government hadn’t been completely inept by any means. It had seen the Internet revolution coming, and had spent a lot of money building up the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. But in South Korea as in all places, the so-called “last mile” of Internet connectivity was the most difficult to bring to an acceptable fruition. Even in North America and Western Europe, most homes could only access the Internet at this time through slow and fragile dial-up connections. South Korean PC bangs, however, jacked directly into the Internet from city centers, justifying the expense of doing so with economies of scale: 20 to 100 computers, each with a paying customer behind the screen, were a very different proposition from a single computer in the home.

The final ingredient in the cultural stew was another byproduct of the recession. An entire generation of young South Korean men found themselves unemployed or underemployed. (Again, I write about men alone here because South Korea was a rigidly patriarchal society at that time, although this is slowly — painfully slowly — changing now.) They congregated in the PC bangs, which gave them unfettered access to the Internet for about $2 per hour. It was hard to imagine a cheaper form of entertainment. The PC bangs became social scenes unto themselves, packed at all hours of the day and night with chattering, laughing youths who were eager to forget the travails of real life outside their four walls. They drank bubble tea and slurped ramen noodles while, more and more, they played online games, both against one another and against the rest of the country. In a way, they actually had it much better than the gamers who were venturing online in the Western world: they didn’t have to deal with all of the problems of dial-up modems, could game on rock-solid connections running at speeds of which most Westerners could only dream.

A few months after it had made its American debut, Starcraft fell out of the clear blue South Korean sky to land smack dab in the middle of this fertile field. The owners of the PC bangs bought copies and installed them for their customers’ benefit, as they already had plenty of other games. But something about Starcraft scratched an itch that no PC-bang patron had known he had. The game became a way of life for millions of South Koreans, who became addicted to the adrenaline rush it provided. Soon many of the PC bangs could be better described as Starcraft bangs. Primary-school children and teenagers hung out there as well as twenty-somethings, playing and, increasingly, just watching others play, something you could do for free. The very best players became celebrities in their local community. It was an intoxicating scene, where testosterone rather than alcohol served as the social lubricant. Small wonder that the PC bangs outlived the crisis that had spawned them, remaining a staple of South Korean youth culture even after the economy got back on track and started chugging along nicely once again. In 2001, long after the crisis had passed, there were 23,548 PC bangs in the country, roughly the same number of Internet cafés as there were 7-Elevens.

Of course, the PC bangs were all competing with one another to lure customers through their doors. The most reliable way to do so was to become known as the place where the very best Starcraft players hung out. To attract such players, some enterprising owners began hosting tournaments, with prizes that ranged from a few hours of free computer time to up to $1000 in cash. This was South Korean esports in their most nascent form.

The impresario who turned Starcraft into a professional sport as big as any other in the country was named Hwang Hyung Jun. During the late 1990s, Hwang was a content producer at a television station called Tooniverse, whose usual fare was syndicated cartoons. He first started to experiment with videogame programming in the summer of 1998, when he commemorated that year’s World Cup of Football by broadcasting simulated versions of each match, played in Electronic Arts’s World Cup 98. That led to other experiments with simulated baseball. (Chan Ho Park, the first South Korean to play Major League Baseball in North America, was a superstar on two continents at that time.)

But it was only when Hwang tried organizing and broadcasting a Starcraft tournament in 1999 that he truly hit paydirt. Millions were instantly entranced. Among them was a young PC bang hanger-on and Starcraft fanatic named Baro Hyun, who would go on to write a book about esports in his home country.

Late one afternoon, I returned from school, unloaded my backpack, and turned on the television in the living room. Thanks to my parents, we had recently subscribed to a cable-TV network with dozens of channels. As a cable-TV newbie, I navigated my way through what felt like a nearly infinite number of channels. Movie channel; next. Sports channel; next. Professional Go channel; popular among fathers, but a definite next for me.

Suddenly I stopped clicking and stared open-mouthed at the television. I could not believe what I was seeing. A one-on-one game of Starcraft was on TV.

Initially, I thought I’d stumbled across some sort of localized commercial made by Blizzard. Soon, however, it became obvious that wasn’t the case. The camera angle shifted from the game screen to the players. They were oddly dressed, like budget characters in Mad Max. Each one wore a headset and sat in front of a dedicated PC. They appeared to be engaged in a serious Starcraft duel.

This was interesting enough, but when I listened carefully, I could hear commentators explaining what was happening in the game. One explained the facts and game decisions of the players, while another interpreted what those decisions might mean to the outcome of the game. After the match, the camera angle switched to the caster and the commentators, who briefed viewers on the result of the game and the overall story. The broadcast gave the unmistakable impression of a professional sports match.

Esports history is made, as two players face off in one of the first Starcraft matches ever to be broadcast on South Korean television, from a kitschy set that looks to have been constructed from the leavings of old Doctor Who episodes.

These first broadcasts corresponded with the release of Brood War, Starcraft’s first and only expansion pack. Its development had been led by the indefatigable Rob Pardo, who used it to iron out the last remaining balance issues in the base game. (“Starcraft [alone] was not a game that could have been an esport,” wrote a super-fan bluntly years later in an online “Brief History of Starcraft.” “It was [too] simple and imbalanced.”)

Now, the stage was set. Realizing he had stumbled upon something with almost unlimited potential, Hwang Hyung Jun put together a full-fledged national Starcraft league in almost no time at all. From the bottom rungs at the level of the local PC bangs, players could climb the ladder all the way to the ultimate showcase, the “Tooniverse Starleague” final, in which five matches were used to determine the best Starcraft player of them all. Surprisingly, when the final was held for the first time in 2000, that player turned out to be a Canadian, a fellow named Guillaume Patry who had arrived in South Korea just the year before.

No matter; the tournament put up ratings that dwarfed those of Tooniverse’s usual programming. Hwang promptly started his own television channel. Called OnGameNet, it was the first in the world to be dedicated solely to videogames and esports. The Starcraft players who were featured on the channel became national celebrities, as did the sportscasters and color commentators: Jung Il Hoon, who looked like a professor and spoke in the stentorian tones of a newscaster; Jeon Yong Jun, whom words sometimes failed when things got really exciting, yielding to wild water-buffalo bellowing; Jung Sorin, a rare woman on the scene, a kindly and nurturing “gamer mom.” Their various shticks may have been calculated, but they helped to make the matches come alive even for viewers who had never played Starcraft for themselves.

A watershed was reached in 2002, when 20,000 screaming fans packed into a Seoul arena to witness that year’s final. The contrast with just a few years before, when a pair of players had dueled on a cheap closed set for the sake of mid-afternoon programming on a third-tier television station, could hardly have been more pronounced. Before this match, a popular rock band known as Cherry Filter put on a concert. Then, accepting their unwonted opening-act status with good grace, the rock stars sat down to watch the showdown between Lim Yo Hwan and Park Jung Seok on the arena’s giant projection screens, just like everyone else in the place. Park, who was widely considered the underdog, wound up winning three matches to one. Even more remarkably, he did so while playing as the Protoss, the least successful of the three factions in professional competitions prior to this point.

Losing the 2002 final didn’t derail Lim Yo Hwan’s career. He went on to become arguably the most successful Starcraft player in history. He was definitely the most popular during the game’s golden age in South Korea. His 2005 memoir, advising those who wanted to follow in his footsteps to “practice relentlessly” and nodding repeatedly to his sponsors — he wrote of opening his first “Shinhan Bank account” as a home for his first winnings — became a bestseller.

Everything was in flux; new tactics and techniques were coming thick and fast, as South Korean players pushed themselves to superhuman heights, the likes of which even the best players at Blizzard could scarcely have imagined. By now, they were regularly performing 250 separate actions per minute in the game.

The scene was rapidly professionalizing in all respects. Big-name corporations rushed in to sponsor individual players and, increasingly, teams, who lived together in clubhouses, neglecting education and all of the usual pleasures of youth in favor of training together for hours on end. The very best Starcraft players were soon earning hundreds of thousands of dollars per year from prize money and their sponsorship deals.

Baseball had long been South Korea’s most popular professional sport. In 2004, 30,000 people attended the baseball final in Seoul. Simultaneously, 100,000 people were packing a stadium in Busan, the country’s second largest city, for the OnGameNet Starcraft final. Judged on metrics like this one, Starcraft had a legitimate claim to the title of most popular sport of all in South Korea. The matches themselves just kept getting more intense; some of the best players were now approaching 500 actions per minute. Maintaining a pace like that required extraordinary reflexes and mental and physical stamina — reflexes and stamina which, needless to say, are strictly the purview of the young. Indeed, the average professional Starcraft player was considered washed up even younger than the average soccer player. Women weren’t even allowed to compete, out of the assumption that they couldn’t possibly be up to the demands of the sport. (They were eventually given a league of their own, although it attracted barely a fraction of the interest of the male leagues — sadly, another thing that Starcraft has in common with most other professional sports.)

Ten years after Starcraft’s original release as just another boxed computer game, it was more popular than ever in South Korea. The PC bangs had by now fallen in numbers and importance, in reverse tandem with the rise in the number of South Korean households with computers and broadband connections of their own. Yet esports hadn’t missed a beat during this transition. Millions of boys and young men still practiced Starcraft obsessively in the hopes of going pro. They just did it from the privacy of their bedrooms instead of from an Internet café.

Starcraft fandom in South Korea grew up alongside the music movement known as K-pop, and shares many attributes with it. Just as K-pop impresarios absorbed lessons from Western boy bands, then repurposed them into something vibrantly and distinctly South Korean, the country’s Starcraft moguls made the game their own; relatively few international tournaments were held, simply because nobody had much chance of beating the top South Korean players. There was an almost manic quality to both K-pop and the professional Starcraft leagues, twin obsessions of a country to which the idea of a disposable income and the consumerism it enables were still fairly new. South Korea’s geographical and geopolitical positions were precarious, perched there on the doorstep of giant China alongside its own intransigent and bellicose mirror image, a totalitarian state hellbent on acquiring nuclear weapons. A mushroom cloud over Seoul suddenly ending the party remained — and remains — a very real prospect for everyone in the country, giving ample reason to live for today. Rather than the decadent hedonism that marked, say, Cold War Berlin, South Korea turned to a pop culture of giddy, madding innocence for relief.

Alas, though, it seems that all forms of sport must eventually pass through a loss of innocence. Starcraft’s equivalent of the 1919 Major League Baseball scandal started with Ma Jae-yoon, a former superstar who by 2010 was struggling to keep up with the ever more demanding standard of play. Investigating persistent rumors that Ma was taking money to throw some of his matches, the South Korean Supreme Prosecutors’ Office found that they were truer than anyone had dared to speculate. Ma stood at the head of a conspiracy with as many tendrils as a Zerg, involving the South Korean mafia and at least a dozen other players. The scandal was front-page news in the country for months. Ma ended up going to prison for a year and being banned for life from South Korean esports. (“Say it ain’t so, Ma!”) His crimes cast a long shadow over the Starcraft scene; a number of big-name sponsors pulled out completely.

The same year as the match-fixing scandal, Blizzard belatedly released Starcraft II: Wings of Liberty. Yet another massive worldwide hit for its parent company, the sequel proved a mixed blessing for South Korean esports. The original Starcraft had burrowed its way deep into the existing players’ consciousnesses; every tiny quirk in the code that Blizzard had written so many years earlier had been dissected, internalized, and exploited. Many found the prospect of starting over from scratch deeply unappealing; perhaps there is space in a lifetime to learn only one game as deeply as millions of South Korean players had learned the first Starcraft. Some put on a brave face and tried to jump over to the sequel, but it was never quite the same. Others swore that they would stop playing the original only when someone pried it out of their cold, dead hands — but that wasn’t the same either. A third, disconcertingly large group decided to move on to some other game entirely, or just to move on with life. By 2015, South Korean Starcraft was a ghost of its old self.

Which isn’t to say that esports as a whole faded away in the country. Rather than Starcraft II, a game called League of Legends became the original Starcraft’s most direct successor in South Korea, capable of filling stadiums with comparable numbers of screaming fans. (As a member of a newer breed known as “multiplayer online battle arena” (MOBA) games, League of Legends is similar to Starcraft in some ways, but very different in others; each player controls only a single unit instead of amassing armies of them.) Meanwhile esports, like K-pop, were radiating out from Asia to become a fixture of global youth culture. The 2017 international finals of League of Legends attracted 58 million viewers all over the world; the Major League Baseball playoffs that year managed just 38 million, the National Basketball Association finals only 32 million. Esports are big business. And with annual growth rates in the double digits in percentage terms, they show every sign of continuing to get bigger and bigger for years to come.

How we feel about all of this is, I fear, dictated to a large extent by the generation to which we happen to belong. (Hasn’t that always been the way with youth culture?) Being a middle-aged man who grew up with digital games but not with gaming as a spectator sport, my own knee-jerk reaction vacillates between amusement and consternation. My first real exposure to esports came not that many years ago, via an under-sung little documentary film called State of Play, which chronicles the South Korean Starcraft scene, fly-on-the-wall style, just as its salad days are coming to an end. Having just re-watched the film before writing this piece, I still find much of it vaguely horrifying: the starry-eyed boys who play Starcraft ten to fourteen hours per day; the coterie of adult moguls and handlers who are clearly making a lot of money by… well, it’s hard for me not to use the words “exploiting them” here. At one point, a tousle-headed boy looks into the camera and says, “We don’t really play for fun anymore. Mostly I play for work. My work just happens to be a game.” That breaks my heart every time. Certainly this isn’t a road that I would particularly like to see any youngster I care about go down. A happy, satisfying life, I’ve long believed, is best built out of a diversity of experiences and interests. Gaming can be one of these, as rewarding as any of the rest, but there’s no reason it should fill more than a couple of hours of anyone’s typical day.

On the other hand, these same objections perchance apply equally to sports of the more conventionally athletic kind. Those sports’ saving grace may be that it’s physically impossible to train at most of them for ten to fourteen hours at a stretch. Or maybe it has something to do with their being intrinsically healthy activities when pursued in moderation, or with the spiritual frisson that can come from being out on the field with grass underfoot and sun overhead, with heart and lungs and limbs all pumping in tandem as they should. Just as likely, though, I’m merely another old man yelling at clouds. The fact is that a diversity of interests is usually not compatible with ultra-high achievement in any area of endeavor.

Anyway, setting the Wayback Machine to 1998 once again, I can at least say definitively that gaming stood on the verge of exploding in unanticipated, almost unimaginable directions at that date. Was Starcraft the instigator of some of that, or was it the happy beneficiary? Doubtless a little bit of both. Blizzard did have a way of always being where the action was…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Stay Awhile and Listen, Book II by David L. Craddock and Demystifying Esports by Baro Hyun; Computer Gaming World of May 1997, September 1997, and July 1998; Retro Gamer 170; International Journal of Communication 14; the documentary film State of Play.

Online sources include Soren Johnson’s interview of Rob Pardo for his Designer’s Notes podcast, “Behind the Scenes of Starcraft’s Earliest Days” by Kat Bailey at VG247, and “A Brief History of Starcraft“ at TL.net.

Starcraft and the Brood War expansion are now available for free at Blizzard’s website.

Andrew Plotkin

July 5, 2024 at 4:25 pm

> Yet Starcraft had what Blizzard liked to call an “asynchronous” design

I bet what they actually liked to call it was an “asymmetric” design!

Jimmy Maher

July 5, 2024 at 7:54 pm

Yes. :) Thanks!

Jeremy Reimer

July 5, 2024 at 5:30 pm

Thanks for the article, it was a good summary of the genesis of the esports scene, something that is near and dear to my heart.

One minor correction: this sentence “The South Korean mobile-phone provider SKY started a new, glitzier league that became even more prestigious than the one founded by Hwang Hyung Jun.” isn’t exactly correct. SKY Mobile didn’t found a new league, they were the sponsors for the 2002 OnGameNet Star League (OSL). The OSL was the premiere Starcraft league for its entire existence up until it disbanded in 2013. There was a second league, the MBC GameNet Star League (MSL) that ran concurrently with the OSL on a separate TV channel until 2011.

Post-2013, the Korean Starcraft scene transitioned away from traditional television stations into Internet streaming channels. Starcraft II was represented by the Global Starcraft League (GSL) which started in 2010, had an English-language broadcast in addition to its Korean cast, and continues to this day. The GSL was originally carried on GOMTV, a Korean video player company, and today it is broadcast by AfreecaTV, which is the Korean equivalent of Twitch, a gameplay streaming service. AfreecaTV also carries a new league called the AfreecaTV Star League (ASL), which covers the original Starcraft: Brood War (now remastered as Starcraft: Remastered)

A fun fact about the ASL: Many of the top players are the same kids who played their hearts out while crammed into team houses, in the original OSL and ASL fifteen to twenty years ago. But now they are adults with wives and kids and a much more balanced life. They make most of their income streaming on AfreecaTV, supplemented by the prize pools from various Starcraft tournaments like the ASL. So it is not all doom and gloom for young esports players.

Jeremy Reimer

July 5, 2024 at 5:38 pm

oops, I meant to type “in the original OSL and MSL fifteen to twenty years ago” above.

Jimmy Maher

July 5, 2024 at 7:57 pm

Thanks for this!

mycophobia

July 5, 2024 at 8:09 pm

I’ve heard the sentiment among pro Starcraft players of the game being a job and not (at least conventionally) fun anymore expressed by pro Go players as well, with a prominent example being a reply Cho Chikun gave to the question “Why do you like Go so much?”: “I hate Go.”

When you take up competitively playing a game, board or video, as a profession you leave behind much of the creativity and wonder that drew you to it in the first place, and you have to just do the thing that wins these long and grueling matches, grinding endlessly along the way. You have to imitate and play against whatever the top players are doing instead of asking “what if I do this…” You get the impression that pro players largely do what they do not primarily because they love it, but because they’re, inexorably, really good at it.

Much meh

July 9, 2024 at 3:18 am

This is exactly why I never cared one whit about “esports”. It utterly ruined the fun behind computer gaming. Noone in esports cares about enjoying the game itself. It’s not fun. It’s purely about marketing and money. I read act 1 and skipped reading act 2. No doubt I’m in the minority. Once a game becomes a job, either because it’s a grind or someone is getting paid, it’s time to find something else to do.

Alianora La Canta

July 15, 2024 at 7:51 am

I like esports… when the participants are amateurs at the esport in question.

I watched quite a few esports competitions during the first COVID lockdown, because some people I was following for their skill at physical sport tried their hand at various esports to stop themselves from getting bored and socialising. They couldn’t make it a job because they still had to find time to do their actual jobs (plus some of them took the opportunity to have more family time and/or take up other hobbies that wouldn’t otherwise have been possible as well).

The resulting streams looked a lot less like professional esports (or even professional sports) and much more like a large-scale LAN party. The LAN party (which was very much a thing in 1998, where The Digital Antiquarian currently is) for me is a good shorthand for what social fun with computer games specifically should look like – fun, laughter, manageable amounts of frustration and problem-solving, conversations sparking around the game and otherwise, and more fun. The part-time esport streamers had time to make silly jokes, laugh and have fun during their competitions, which is part of the attraction of gaming. (The particular ones I was following were professional racing drivers, but I believe there were similar streams going on with athletes in other sports and, probably, other jobs where mass unemployment/under-employment followed the “stay at home” orders). It was fun to watch and clearly everyone involved found it fun to play.

Then summer 2020 came, workplaces got ready to re-open and the temporary esports streamers got ready to do their usual jobs. I did have a look at a professional esports stream and decided it looked less fun than playing an actual computer game myself. The participants looked like they were bored and that it had become a dull routine job for them (which is not how I like to treat work, let alone a passion). Unsurprisingly, I went back to watching physical sport at that point – the fun was different, but there were people actually having fun doing their passion and earning money as well…

Maybe that’s the secret: do esports as a fun side thing, treat it like a game rather than a job and accept your wages will be in something that doesn’t ruin your hobby.

Gwydden

July 5, 2024 at 8:19 pm

So how did *you* feel about Starcraft playing it this time around? How does it compare to other RTS you’ve played for the blog so far?

Not Fenimore

July 6, 2024 at 3:04 am

Well, he at the very least beat the first campaign – I saw that second screenshot minimap and my brain immediately shouted “THE BIG PUSH! Duke beats the tar out of Delta Squadron over Tarsonis!”

…why yes, I’ve played the SC1 campaign too many times.

Vince

July 9, 2024 at 5:02 am

Heh, a friend of mine could recite Arcturus Mengsk’s speech at the end of the Terran campaign word for word.

That (partial) ending is so bold and memorable.

Jimmy Maher

July 6, 2024 at 9:02 am

The short answer is that the gameplay just isn’t for me. I find it stressful, and not in a good way. But I can say from the few hours I did spend with Starcraft that it’s a lovingly polished game that does what it sets out to do ridiculously well. Credit where it’s due. It’s not you, game, it’s me. Etc.

A slightly longer answer is that this blog has long gone down two paths. There’s the close examinations of games from this individual player’s perspective, and a broader cultural history of gaming. This can sometimes create a certain cognitive dissonance. Some games that appear here interest me for the one reason, some for the other, some for both. Starcraft definitely falls into the “cultural history” camp. (My previous article, on The Journeyman Project series, is a prime example of the other type.)

I’ve occasionally considered abandoning the cultural-history angle and just writing about games I do find personally engaging here. But I’m loath to do that because a) I do find subjects like the South Korean esports scene genuinely fascinating, and b) I think there is if anything *more* need for these kinds of studies than more slices of the “old guy plays old games” genre, which is pretty well-represented elsewhere on the old blogosphere. (Do people still use that word?)

In the past, I have tried to square the circle to some extent by inserting a paragraph explaining that “this game is not really for me, but it might be for you.” Blah, blah, blah, and so on. But that was getting a little bit repetitive for me to write, and I suspect it was getting tiresome for many of you to read. And I think it occasionally came across as demeaning to the game or the people who love it, even though I really hadn’t intended it that way. So, I didn’t do it this time. I should write sometime about the difference between experiential and zero-sum gaming. I’ve always been in the first camp; I come to games looking for an experience more so than I’m looking to win. That can create a barrier between me and games that are more focused on the competitive aspect. But this article wasn’t the right place to go into that either.

All that said, I certainly do intend to keep giving every game I write about a good, solid try. If I like or love it, you’ll hear about it. If I’m less enamored, I’ll pan it only if it deserves panning — i.e., if it fails to be the thing it sets out to be, rather than what this grumpy old gamer would like it to be. That goes for the RTS genre as well as all of the others. The next game I’ll tackle there will be Homeworld, the first RTS to move from 2D sprites to 3D graphics. As always, I will go into it hoping to love it. If I do, you’ll definitely hear about why in some detail. If I don’t, there’s a lot still to say about its innovative technology, which has definitely earned it a place in any comprehensive set of histories like these.

Gwydden

July 6, 2024 at 11:05 am

All perfectly reasonable and well put. I asked because the personal touch is a big part of what makes these kinds of histories compelling, so I’m always interested in what the “old guy” thinks about the “old games” he plays even if I don’t agree.

I’ll say that I’m very much in the narrativist/experiential gamer camp, so I do take some issue with folks treating RTS as a primarily competitive genre. Statistics I’ve seen for Age of Empires 2 and Starcraft 2, for example, suggest the overwhelming majority of players don’t touch competitive multiplayer at all and just play the campaign, custom maps, and co-op. The same is likely true of other popular RTS titles.

killias2

July 6, 2024 at 6:21 pm

Yeah, I feel like the emphasis on the MP is mostly earned here but.. not entirely? Like Brood War may very well have the best SP RTS campaign ever put together, and Starcraft and BW have, imo, one of the only good RTS storylines. I also think modern RTS games jump on the MP focus way too much. You lure new players with SP and then, maybe, they might get into MP. Oh well.

Starcraft is obviously a MP phenomena where I spent hundreds of hours as a youth, but I probably never would’ve played it at all without the Warcraft 2 and Starcraft campaigns grabbing my attention.

I also feel that the inherent joy of RTS games, scrolling a big map; controlling lots of cool units; building a base in a way you want; choosing your own path to build up and expand, often gets lost with the focus on MP and actions per minute these days. If RTS games ever come back, it’ll be because some developer taps into that more basic set of joys rather than bringing the Brood War-era MP magic back to life.

glorkvorn

July 7, 2024 at 5:26 am

Agreed. The MP couldn’t have been as popular as it was, without the game first having a great single player mode. Both the campaign, and the custom skirmishes against the AI, were excellent. It’s a lot less stressful than playing competitive multiplayer.

One big difference: the game allows you to change the speed. But in multiplayer it’s always set to “fastest,” which is very fast indeed. So there are all sorts of fancy abilities you can use in a slow single-player game, but they become almost impossible to do in a high-speed competitive match.

Part of the reason that watching progaming matches was exciting was that the pros actually *could* pull of those moves, and win games with them. Boxer, especially, was not just a great player, but very much a showman who would use fancy moves to entertain the crowd.

They say that “over time, players will optimize the fun out of everything.” Sadly that’s true, it’s hard to experiment and be creative when everyone is trying to kill you as fast as possible. But it’s a credit to the game that people could do that for so long.

Sebastian Redl

July 7, 2024 at 6:11 am

I think GiantGrant’s video on this is relevant here. He brings up these statistics and talks about the implications.

https://youtu.be/XehNK7UpZsc?si=sfjgXBOgDJjGkwY6

Adamantyr

July 7, 2024 at 3:39 pm

I was playing UO at the time Starcraft came out, and I had a similar feeling about it. Loved the setting and narrative, disliked the stress of RTS play. I usually would end up turning on cheat codes after awhile.

In particular, one thing Starcraft did was force you to micromanage your troops. If you told them to “move” somewhere, they would, and then sit there and let enemies attack them because you didn’t tell them to “attack” that area. SO infuriating. These are the kind of tasks that as a software engineer I seek to automate.

Sniffnoy

July 7, 2024 at 4:12 pm

I mean, you could right-click (IIRC?) to move-attack. But that option was kind of hidden, I sure missed it when playing for the first time…

dsparil

July 8, 2024 at 12:20 pm

I greatly preferred the fact that Total Annihilation let you set an AI per unit with separate movement and attack settings. It made it less of a chore to play, and the gameplay was very advanced for the time period. Starcraft felt like a step down in every way except presentation. It’s a shame that it seems like a forgotten game now despite selling over 1.5 million copies.

GamingHistoriography

July 8, 2024 at 2:36 am

Please keep doing the cultural history pieces as well as your more personal play through based articles! I really enjoy your writing and the rigorously sourced but journalistically written style is perfect for the subject matter. As a fan of history and also gaming with more time to read than to play these days, your work hits a sweet spot for me. I should really contribute to your Patreon, will do that now.

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2024 at 7:37 am

Thank you for your support!

Horkthane

September 4, 2024 at 3:49 pm

I’m kind of sad to hear you didn’t enjoy StarCraft. IMHO it had one of the most forgiving single play campaigns I think I’ve ever played, minus a few Protoss levels towards the very end. The enemy AI isn’t very aggressive at all, and you are given enough resources to try several times to crack the enemies defenses. I actually beat it again a few years ago and enjoyed it immensely.

All that said, I think I was 14 when StarCraft came out, and RTS was still intimidating enough to me at the time that I mostly played them single player with the built in cheat codes. I wanted to experience the story and the gameplay scenarios, without having to sweat the details. So I’d make liberal use of god mode, extra resources, and instant production.

If you consider your time with StarCraft over, I get that. But I also wouldn’t be shy about just using the built in cheat codes either. After all, they were put there for a reason. There is no wrong way to play. I’d say this goes for a lot of 90’s games that had built in cheats in fact.

Sebastian Redl

July 5, 2024 at 10:16 pm

> The 2017 international finals of League of Legends attracted 58 million viewers all over the world; the Major League Baseball playoffs that year managed just 38 million

Meanwhile, the FIFA World Cup 2022 final was watched by an estimated 1.5 billion people according to FIFA.

Baseball and basketball just aren’t very international. Especially the American league playoffs.

On another note, MOBAs aren’t RTSs.

Sebastian Redl

July 6, 2024 at 7:00 am

I probably shouldn’t write comments on a phone at midnight. The terseness looks very rude in the light of day.

Really interesting article about the origins of one of my favorite games. Especially the start of the Starcraft scene in SK. Despite being an avid watcher of professional Starcraft 2, I never knew how it got started.

Jimmy Maher

July 6, 2024 at 9:12 am

They don’t compare with international football, no, but what does? Basketball is more popular than you’d expect here in Denmark. My neighbor’s son is obsessed: spends an hour or more every day outside shooting hoops, watches tons of games on television, etc. Baseball is absolutely huge in Central and South America and parts of Asia — in many ways bigger than it is in North America, where the sport has rather fallen on hard times in recent decades. I would guess that three-quarters or more of that 58 million were watching from outside North America. Basketball is far more popular now within North America.

Leo Vellés

July 8, 2024 at 1:31 pm

Maybe in central america, but the only country in South America where baseball is huge is in Venezuela. In the rest of the sub continent football (or soccer, as americans call it) is the most popular sport way, way above others

M. Casey

July 5, 2024 at 11:47 pm

> Then, accepting their unwonted opening-act status with good grace

Did they not get paid? Is this a pun?

mycophobia

July 6, 2024 at 12:53 am

unwonted means unaccustomed to, unused to. compare: “as is his wont”, i.e. “as he usually does” or “as he would normally do in this situation”

M. Casey

July 6, 2024 at 1:45 am

Huh. I have never read that word. I should’ve looked it up before saying anything.

Thanks!

stepped pyramids

July 6, 2024 at 12:31 am

Great article.

League of Legends is typically considered a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena (MOBA), not an RTS, although the genres are related — in fact, the first MOBAs started as custom StarCraft and Warcraft levels. The two genres have some similarities in visuals and controls, but the gameplay is substantially different (each player controls a single character, for one thing).

Jimmy Maher

July 6, 2024 at 9:19 am

Thanks!

TTM

July 6, 2024 at 1:15 am

BroodWar and SC2, together, are such a local (global?) maxima of their genre that they basically killed competition on RTS (as others have noted, LoL is not an RTS).

25 years later and, even tough some new candidates are appearing, still RTS is, for all practical purposes, Starcraft.

Are there other similar cases in gaming?

Gnoman

July 6, 2024 at 2:56 pm

It doesn’t have the same multiplayer cachet, but Freespace 2 is widely credited with killing the “cinematic starfighter pilot” genre begun by Wing Commander, entirely because the quality of the game was so great that nobody could compete with it.

Not sure if that’s statistically borne out (it could have merely been a change in gamer tastes or an inability of developers to create proper WOW factors with new tech in a genre that originally started because a space shooter can have extremely minimal graphics on most of the screen), but there hasn’t been any new hits in the once-thriving genre with multiple franchises since FS2.

John

July 6, 2024 at 10:59 pm

I’m afraid I don’t believe the “because it was too good” corollary to the “Freespace 2 killed space sims” theory. Frankly, I don’t believe the “Freespace 2 killed space sims” theory either. I personally lean more towards the “mice displaced joysticks as common PC peripherals” and “other genres were more profitable” theories.

Chase

July 10, 2024 at 10:27 pm

Yeah, FS2 did not kill space-sims. Joystick games – space-sims, flight-sims – as a genre declined rapidly after 1998. There’s a variety of reasons for that but in the case of flight sims it was a shrinking, aging audience demanding more and more “fidelity” (leading to unprofitable development). For space sims I’m thinking the original Star Wars kids grew old.

New kids came along and decided Halo and CoD were the shiznit. Then new kids came along and decided it was Minecraft and LoL. Then PUBG. Then… hmm. Being an old timer (with expensive joysticks, a q3, and niche flight sims) I kinda have little idea what’s popular now, and don’t care.

Alianora La Canta

July 15, 2024 at 8:01 am

If space sim developers could figure out how to make space flight feel accessible, awesome and in depth on a gamepad, then the genre could come back into action. However, Freespace 2 did also come with a sense of completion – the “this is the current state of this particular art done to perfection”. A combination of the other explanations Gnoman and John suggested explain why no new “state of the art” was in a position to replace this.

Vince

July 8, 2024 at 4:06 pm

After SC/Brood War there still quite a few RTS that were relatively successful and tried to do their own thing, on top of my mind Age of Empires 2, Total Annihilation, Homeworld.

SC2… yeah, that was kind of freaky, it kind of heralded both the peak and the death of a genre unlike anything else I can think of.

Alex

July 6, 2024 at 6:18 am

I still have fond memories of Starcraft. Really liked it when it came out and I´m curious if I still would enjoy it today. I never had the feeling that it was something special compared to the tons of RTS-Games back then, but the quality was definitely a lot higher.

Speaking about Korea, that was a really interesting part of economic history I didn´t know about. Until today I thought that South Korea was always doing quite well as a whole, apart from having to deal with the history of their border, of course. Among the group of friends I had as a student was a Korean Exchange Student I still remember fondly. He was just a great guy and we had a lot of fun together, but he never spoke in detail about his country.

Regarding E-Sports, I see it in a similar way you do. I don´t want to stir up a discussion, so I just say that I can´t identify myself with this culture when it´s corporate driven.

fform

July 6, 2024 at 10:04 am

This article just makes me hope that World of Warcraft still exists by the time you get around to writing about it.

I still have my copy of Starcraft 1.0 in a box along with a few other CDs that survived the many moves over the years. As coincidence would have it, I picked up a complete boxed set of the Starcraft Battle Chest at Goodwill about two weeks ago for $10, replete with down-sized Prema strategy guides (if they only knew!) and a Blizzard product catalog from the time with a fair amount of vaporware listed. I don’t know how much of it I played online back in the day, far less than my FPSes, but I remember getting fairly far in the campaigns and that every gamer I knew at school had a copy.

Hresna

July 6, 2024 at 11:26 am

What always fascinated me about this game, or impressed me, rather, is just how they managed to keep it both asymmetric and yet balanced… I have to think that it could only be achieved through extensive play-testing with, at least, fairly decent players to begin with.

It’s one thing for the campaign to be tuned well for player progression through the races, but that the game stood the test of time in multiplayer is probably the clearest sign that they struck that balance exceptionally well, however they did it. #nozergrush

John

July 6, 2024 at 12:04 pm

I have long felt that Westwood games get a bad rap for their supposedly symmetric factions when in fact Westwood was experimenting with asymmetric factions long before Blizzard ever got around to it. It’s true that the factions in Command & Conquer are roughly similar at the lower end of the tech tree to the point that they even have some infantry units in common. At the far end of the tech tree, however, they diverge significantly. GDI has absolutely nothing like NOD’s stealth or flame tanks and NOD has no air units like GDI’s Orca. Compare that to Warcraft II, where every unit on the one side has a nearly exact reflection on the other. The only difference between a Paladin and an Ogre Mage, apart from the sprites, is that one has a spell that heals other units and the other a spell that improves their combat performance.

To my mind, StarCraft is most notable for introducing two ideas to the set of common gaming knowledge: first, the idea that RTS games are first and foremost multiplayer games and, second, that RTS games should be heavy on micromanagement. Jimmy’s already covered the multiplayer stuff, so I’ll limit myself to talking about the micromanagement. I sometimes suspect that Blizzard’s innovation of giving every last unit one or more player-controlled spells or special abilities is what killed the RTS as a popular genre. A lot of things happen simultaneously in an RTS. In pre-Starcraft games, the name of the game was to get the right units to the right spot at the right time. Post-Starcraft, you need to not only do that but manage all their abilities as well. It’s a significant increase in cognitive load. I note that the genre that displaced the RTS, the MOBA, keeps the micromanagement aspect of post-Starcraft games but reduces the cognitive load by limiting the player to a single unit.

Ishkur

July 7, 2024 at 1:08 am

I agree with the fact that Starcraft was not the first asymmetric game.

Command & Conquer had an “strength vs speed” kind of rock-papper-scissors balance to its gameplay. Every unit had a corresponding unit that could counter it, but generally the GDI armies — with their NATO/UN-backed money and economies — were bigger, stronger, better equipped and overpowered. Their strategy was always brute force and frontal assaults, with the mammoth tank and Orca choppers doing the heavy lifting.

The Brother of Nod, on the other hand, was a terrorist organization backed by dark money and limited resources and so were always leaner and cheaper. Their strategy emphasized stealth, speed, and cunning, with the flame units and stealth tanks the main weapons.

Alianora La Canta

July 15, 2024 at 8:06 am

Even Dune 2 has an asymmetric last couple of missions, because each side gets a different specialist unit (they also have a restriction, but that’s not a big factor for most play styles in that particular game). Knowing how to use these well was the difference between the last mission being done in 30 minutes and 2 hours (that, and being able to handle more opponents than previously – by Starcraft’s time, this would probably have been 2 separate missions of teaching experience).

What Starcraft did was to make that difference important for the whole campaign, which meant that it was possible to experiment with simpler iterations of using the ability first, then find more complex situations in which those differences become important. It requires a different playstyle instead of simply suggesting it.

Gnoman

July 6, 2024 at 3:02 pm

Starcraft is a game that shares a very specific accomplishment with only one other game. It was bundled with the Brood War expansion pack and some strategy guides and put on sale for the bargain price of twenty dollars. And then remained on store shelves at that price, new, for nearly 20 years. I saw it for sale at a regular store, new in box, as late as 2019 just before most of the local department stores finally euthanized the remnants of their PC software departments.

The only other game I ever saw have that sort of brick-and-mortar longevity? Diablo II, another Blizzard game. Which also was bundled with the expansion pack and some strategy guides and put on sale at a bargain price that stayed unchanged until the destruction of the software section.

Alianora La Canta

July 15, 2024 at 8:14 am

The Sims 2 was still being sold in some retail outlets in my local area 13 years after it was released (released 2004, last new copies I saw on sale 2017), despite EA making it free in 2014 at the start of its “end of support” phase. It might have been available longer, except that the new PC software departments likewise disappeared from everywhere except one specific computer shop that didn’t sell games. It was sharing space with a bunch of hidden-object games that were typically 3-5 years newer, because these were the only remaining boxed games the shops still having such departments in 2017 could sell. (I suspect that the sort of people who were interested in Starcraft and Diablo II were by then downloading their games instead of purchasing disks).

Jacob S

July 6, 2024 at 3:11 pm

Are there some classic games with commentary that I could watch? I’m sure there’s a slew of stuff, but finding a good starting point is the thing.

Jimmy Maher

July 6, 2024 at 4:09 pm

You can find the 2002 final that was such a big coming-of-age moment for South Korean Starcraft here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iW-LbOvcMT0&list=PL38oGeTewl6aKQ2_ciD0un6vfrCwUMENc&index=21. The obvious problem with watching this and other matches is that the commentary is all in Korean…

Anonymous

July 9, 2024 at 8:09 am

If you’re fine with recently played matches, the ArtosisCasts channel on youtube has lots of pro games with English commentary. The problem with watching “classic games” today is that the quality of videos from that time tends to be very low (grainy 144p youtube videos) and as Jimmy mentioned, it’s all in Korean.

For old games, Liquipedia has links to old VODs scattered all over the place https://liquipedia.net/starcraft/Portal:Progaming

Bob

July 6, 2024 at 5:57 pm

RTS died when everyone started stealing games by rebranding them MMO, everyone was expecting dedicated servers + level editors to continue forever in the mid 90’s, the big modding and multiplayer BOOM over IPX emulators. When garriot and theif raph koster came up with a brilliant idea to steal the network multiplayer code out of the game code it in a fraudulent way and sell it back to public as a new kind of game minus ownership, was the death of RTS.

Publishers saw Ultima online, everquest printing money like no tomorrow, so the focus now was on converting all PC games to client-server apps over time, then we got carpet bombed with the CANCER known as STEAM in 2003, once game companies had control over their games that was the death of games for fun because now in game stores, microtransactions were the focus, not making great games.

The success of mmos killed gaming as a whole because the mad amounts of money made off stupid computer illiterate public. Go get a copy of Transformers fall of cybertron for PC, and try to use its multiplayer, then go get a copy of the original Unreal, and unreal tournament, your mind will bend that games from the mid to late 90’s are more advanced technically then a modern AAA game from 2014 using the latest (at the time) unreal engine. We’ve gone backwards in time.

Conrad Hart

July 12, 2024 at 4:47 pm

“Go get a copy of Transformers fall of cybertron for PC, and try to use its multiplayer, then go get a copy of the original Unreal, and unreal tournament, your mind will bend that games from the mid to late 90’s are more advanced technically then a modern AAA game from 2014 using the latest (at the time) unreal engine.”

Could you please elaborate on what you mean by this? Do you consider the Unreal games’ multiplayer modes to be better? If so, how?

(I am more of a single player gamer so I do not know what makes a good multiplayer mode.)

Martin

July 6, 2024 at 9:09 pm

“…. from a kitschy set that looks to have been constructed from the leavings of old Doctor Who episodes.” Now this is an insult!

Elyv

July 6, 2024 at 11:30 pm

This is a great article, I know a ton about starcraft and I follow the pro scene to this day and I still learned a lot. The thing it’s missing, however, is the massive resurrection in the Korean Starcraft scene in the last 6 or so years. There’s now many players who make their living streaming Brood War as opposed to the old team house system because of how abusive it was. Players have been leaving sc2 for sc1 lately because it’s much more lucrative.

R

July 7, 2024 at 5:35 am

Good summary for someone who wasn’t there at the time. Correction: Ma Mae Yoon -> Ma Jae Yoon

Jimmy Maher

July 7, 2024 at 7:47 am

Thanks!

Chris G

July 7, 2024 at 9:26 am

Fantastic article! Thanks for writing it!

I grew up in New Zealand and was working in New Zealand at the Meat Industry Research Institute of New Zealand (MIRINZ) as a PC and Network Support guy when StarCraft was being finalized. I was in the Beta program and enjoyed online multiplayer because I would take a few friends into work on the weekends and we’d play with low latency since MIRINZ had a super-fast connection to New Zealand’s internet gateway. I got into StarCraft 2 again with a group of friends years later working for Microsoft in Fargo North Dakota around the time that Day9 was doing SC2 commentary and content. To this day, as a 46-year old guy with two kids approaching their teenage years, my guilty pleasure is watching SC2 streamer content from UThermal . The combination of collaboration, competition, strategic thinking, and fast action of SC and SC2 are still a draw to me all these years later

Russ Newcomer

July 8, 2024 at 3:22 pm

“Blizzard artist Pat Wyatt” in the 4th paragraph is incorrect.

Super nitpicky, but Pat Wyatt was a programmer, not an artist, which you do correctly refer to him as later in the article

Link to his blog which has some programming related content on Starcraft and Warcraft. https://www.codeofhonor.com/blog/

Good article, although disappointed that it does not mention the contrasting and (tongue in cheek for flame wars that happened 25 years ago) far superior Total Annihilation.

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2024 at 5:55 pm

Thanks!

Garry Perkins

July 9, 2024 at 5:33 pm

I have played StarCraft all these years and still watch SC2 on youtube. I love the star players, and I used to donate when there were still American teams. I still love to watch Maru play, but I miss Bomber and Polt. I miss how the scene died down. It was my favorite pastime ten to 14 years ago. If I lived in Europe I bet I would still be in that scene.

gamer

July 12, 2024 at 7:56 pm

kespa vs blizzard seems to be missing around the sc2 launch; I would argue that was a major blocker against sc2’s success in Korea

FincasKhalmoril

July 14, 2024 at 9:20 am

Excellent article! I really enjoyed reading it.

Just one small thing: „ But far more importantly, each of the factions was truly unique, in marked contrast to those of Warcraft and its arch-rival RTS franchise Command & Conquer. In those games, the two factions’ units largely mirrored one another in a tit-for-tat fashion, merely substituting different names and sprites for the same sets of core functions.“

The above said was true for Dune 2 and the first two Warcrafts, but not for Command & Conquer, which actually invented asymmetric play. With the exception of a few basic units and buildings all the units were unique for either the GDI or NOD.

Starcraft‘s stroke of genius was that it took this lesson to an extreme: three, not two unique sides, unique buildings AND even unique ways to gain resources. No RTS had ever felt so different, more like playing three different games than playing a game with three different armies.

Jimmy Maher

July 14, 2024 at 4:08 pm

I cleaned this up. Thanks, both to you and those who mentioned it earlier.

Doug Orleans

July 15, 2024 at 8:12 pm

Guillaume Patry was recently on the Korean reality game show The Devil’s Plan (currently streaming on Netflix). It’s a fun show, like Big Brother but far more cerebral. They mentioned he was a pro gamer but I didn’t know how legendary he actually was!

Busca

July 24, 2024 at 6:31 am

Regarding the genesis or rather precursors of e-sports, there was an article this spring about Wizard vs Wizards, an event in 1982 where twelve game developers (including Ken Williams) competed in each others’ games for a USD prize, presented by a known actress and recorded for TV.

Apparently it was designed to be repeated each year, with the winner facing of against new opponents, but at the time it seems it failed to generate enough interest / viewers.

Adam Sampson

July 24, 2024 at 5:16 pm

I played Starcraft at LAN parties in the late 90s – I never played the single-player campaign – so for me the experience of the game is absolutely tied to the social experience of playing it with a group of friends who had different preferred sides and play styles. Not only was the game well balanced, it was also very accessible for new players.

(Picky comment: “sent it off to be burnt onto hundreds of thousands of CDs” – mass-produced CDs are pressed, not burned.)

Jimmy Maher

July 26, 2024 at 8:25 am

Thanks!

Darkling

September 11, 2024 at 4:26 pm

‘Fluorescent’ is misspelt in the caption for the first graphic.

Also, there’s a difference between a ‘cut scene’ (ie a scene that has been cut or excised) and a ‘cutscene’ (or, less commonly, ‘cut-scene’) in which the action cuts away to a different perspective.

Jimmy Maher

September 13, 2024 at 2:14 pm

Thanks!

TacTican

September 21, 2024 at 4:14 pm

One thing I believe that contributed massively to the success of StarCraft and Brood War, which is rarely touched upon in any of the commentary that I’ve read, is that the games shipped with a map editor which was just the exact right blend of simplicity, approachability, rigidity, flexibility, and power.

Prior to StarCraft, map editors (if they existed at all, a la Warcraft II) could only produce very simple maps with extremely limited win conditions and had almost no scripting ability, meaning in practice a mapmaker could only produce skirmish maps. These maps differed only in the number of player slots, the terrain, and the resource allocation on the maps. StarEdit, on the other hand, had an easy to understand trigger system which could be learned via experimentation but still offered considerable latitude of use and versatility. It’s said nowadays that single-player is a gateway to multi-player; equally important is the single-player to custom map pipeline, which expanded on the PvE content for those who played the campaigns and wanted more. StarCraft players made their own campaigns and branched out into an astounding cornucopia of custom maps, and thanks to the advent of Battle.net these maps could be shared and played by anyone over the Internet. This is extremely important both for the growth of StarCraft as a whole (because players could produce and access an endless stream of StarCraft content) and for the development of subsequent video game genres. In fact, it is probably not an exaggeration to say that at least two modern day video game genres (wave defense/tower defense, arguably; MOBAs, inarguably) had their genesis in StarCraft custom maps.

Yet for all its power and flexibility, StarEdit still operated in some fixed ways. You couldn’t change unit behavior: Firebats were still up close units with a fixed range of 2 and concussive splash damage, all Dragoons moved at the exact same speed, and let’s not get started on pathfinding subroutines. This contributed to one of StarCraft’s two greatest strengths as an e-sport, namely its supreme visual readability: single, multi, and custom map players all knew exactly how units behaved when watching televised matches. Even today when we watch old grainy video in 144p quality it’s not hard to see what is going on.