At the conclusion of my previous article on Sierra Online’s corporate history, we saw how Ken and Roberta Williams moved their company’s headquarters from the tiny Northern California town of Oakhurst to the Seattle suburb of Bellevue, home to Microsoft among others, in September of 1993. They did so for a mixture of personal and professional reasons, as Ken has since acknowledged. Their children were getting older, for one thing, and the schools in Oakhurst were far from world-class. Additionally, life in general as the biggest fish of all in the fishbowl of a company town that Oakhurst had become wasn’t always pleasant; for example, Ken has claimed that his kids were at times bullied by “the children of former Sierra employees who had a grudge against Sierra.” Some other former employees suspect still another reason for the move to Bellevue, one that Ken neglects to mention: the fact that Washington State had no personal income tax, while California’s was the highest in the nation.

Still, there are no grounds to doubt that the public reason Ken gave for the move back in the day was indeed a major part of the calculation: the need to recruit the sort of seasoned business talent that could take Sierra to the next level. The company’s annual revenues had grown every single year since 1987, more often than not substantially, and this was of course wonderful. But less wonderful was the fact that profits had never been as high as that progression would imply; Sierra had a knack for spending almost every dime they earned. Of late in fact, the bottom line had dipped sharply into loss territory even as revenues continued their steady climb. Under pressure from his shareholders, Ken Williams realized that he had to find a way to make his company start to pay off. He believed that doing so must entail assembling the kind of top-flight management team which could only be found in a big city. He’d been seeking a rock star of a chief financial officer for a long time from Oakhurst to no avail. Ken Williams:

I had hired a San Francisco-based company, Heidrick & Struggles, to lead the search, and after months of getting nowhere I called my contact at Heidrick in frustration. “Why do you keep sending me B and C level candidates?” I asked. I was tired of having my time wasted interviewing candidates who were not at the level I was seeking. The answer came back without hesitation: “Ken, you’re aren’t getting it. No A player wants to move to Oakhurst.”

Nine months after the move to Bellevue, Ken finally found his rock star in the form of one Mike Brochu, a financial whizz who had spent the last nineteen years working for Burlington Resources. The man whom Ken still describes as “probably the best hire I ever made” was a garrulous Texan who “inspired confidence in everyone around him.” Not coincidentally, Sierra began to display a newly hard-nosed, bottom-line-focused attitude toward their business from virtually the moment of his arrival. As one of his first projects, Brochu led the negotiations that resulted in the sale of The ImagiNation Network, Sierra’s visionary but perpetually money-losing online-gaming service, to AT&T for $40 million in cash in November of 1994.

Meanwhile Sierra implemented a significant shift in their product-development strategy. For many years now, the heart of the company’s identity had been a set of long-running adventure-game series, most of which worked the word “quest” somewhere into their title. Dodgy from the standpoints of both writing and design though they sometimes were, they’d all displayed enough lovable qualities to worm their way into fans’ hearts. I’ve described in earlier articles how Sierra fandom could feel like belonging to a big extended family. These games, then, were the cousins whom you could always expect to see at the family reunion every couple of years, dressed perhaps a bit differently than last time around but always the same person at bottom. They were comfortingly predictable, and that was exactly how the fans liked them.

But for all that these ramshackle, puzzle-heavy adventure games were good at cementing the loyalty of the already converted, they were less equipped to unleash the sort of explosive growth Sierra was now after. It was a pivotal moment in the history of the personal computer, as Ken Williams and Mike Brochu well recognized. In 1994, more home computers would be sold than televisions, as consumers, tempted by the ease of use of Microsoft Windows, the magic of multimedia, and rumors of a thing called the World Wide Web, jumped onboard the computing bandwagon in staggering numbers. These people didn’t know a King’s Quest from an Ultima. Reaching them would require a different sort of game: fresher, hotter in the Marshall McLuhan sense, more in tune with what they were seeing on television and at the movies. It seemed like it was now or never for Sierra to capture their interest, even if it meant that some of the old fans were left feeling a bit abandoned.

So, Sierra’s new Bellevue management team took a hard look at their existing series in order to decide which were expendable and which were not. King’s Quest, the company’s longstanding flagship series, which already enjoyed a measure of name recognition outside the traditional computer-gaming ghetto, would have been an obvious keeper even if it hadn’t been the baby of Roberta Williams. Leisure Suit Larry also had proven appeal with non-traditional demographics, and was thus also a no-brainer to keep around. Space Quest was an edge case, but the managers decided to green-light one more game, if only to throw a bone to the old-school fans. But Police Quest would get revamped from a line of adventure games into a line of tactical 3D action games, while Quest for Glory would get the axe entirely. Going forward, the main focus would be on bigger-budget adventures employing filmed human actors, for which Sierra was now building their own sound stage down in Oakhurst at considerable cost. They would make fewer of this new type of adventure, but each of them would be a flashy, high-fidelity production, able to appeal to a mass market weaned on big-screen televisions and CD players. The idea was to make the release of each Sierra adventure from now on a real event.

Unfortunately, the transition from one product strategy to another came with a pitfall: it would take some time to bring it off, meaning that 1994 would be an unusually quiet year in terms of new games. And that reality, combined with the new management team’s more hard-nosed attitude, meant that some of the folks in Oakhurst must lose their jobs. Among them were Corey and Lori Cole, the husband-and-wife team behind Quest for Glory, who saw their roles cancelled along with the fifth game in their series, the most impressive of all the series in the Sierra lineup in terms of design ambition and innovation. Corey recalls a scene which made it all too clear to everyone present that Sierra was now being run as a business, not a family: “All employees in the meeting were handed envelopes; about half of them contained ‘pink slips’ notifying them that they no longer worked for Sierra. Those employees were escorted back into the building and watched as they retrieved personal belongings from their desks.” Layoffs are never easy. Corey especially remembers the sight of Gano Haine, who had worked on Sierra’s two EcoQuest games and Pepper’s Adventures in Time, standing in the parking lot crying: “Sierra had been her dream, and she was so thrilled to have gotten the job there.”

During this year of wrenching transition, Sierra released just one new Oakhurst-built adventure game, making it their least prolific year in that respect in almost a decade. Thankfully for the bean counters, the game in question was the latest installment in Sierra’s most bankable adventure series of them all. King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride was a typical entry in a series that had been Sierra’s ever-evolving technological showpiece since 1984. But then, that description in itself implies innovation on at least a technical front, and this the new entry certainly delivered.

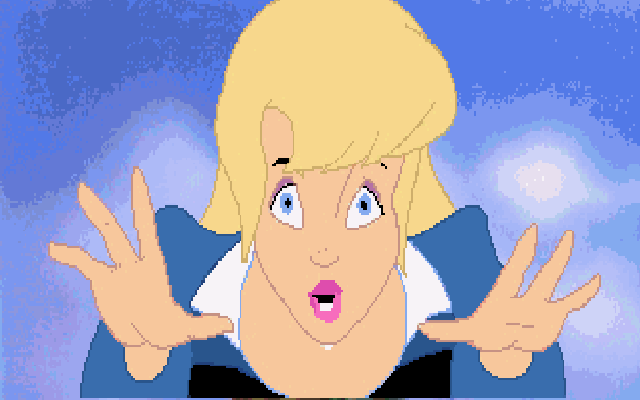

The King’s Quest VII opening movie. Ken Williams has often said that Walt Disney was one of his biggest role models. With King’s Quest VII, this influence became almost distressingly literal.

Although it did not employ filmed actors, King’s Quest VII was indicative in another way of Sierra’s new direction: rather than an interactive movie, it aimed to be an interactive cartoon worthy of comparison to the likes of Disney, an ambition which required it to look beyond Sierra’s own stable of talented in-house artists for some of its visuals. Ken Williams first reached out to an up-and-coming animation studio known as Pixar. He even spoke personally with Steve Jobs, Pixar’s chairman and majority owner, but in the end the studio proved to be simply too busy working on Toy Story, their first full-length feature film, to take on this task as well. So, Sierra ended up contracting sequences out to no fewer than four other outside animation studios, in addition to employing their own artists to create what truly was an audiovisual extravaganza by the standards of its time. King’s Quest VII went full Disney, as Charles Ardai described in his review for Computer Gaming World magazine.

I tried this game on my mother (a big fairy-tale fan), who asked, “Is that a game from Disney?” When I replied in the negative, she said, “But they’re trying to do Disney, right?”

They are indeed. From the opening frames, where drops of dew in an enchanted forest drop on the tummy of an enchanted ladybug, to the scene a few seconds later in which lovely Princess Rosella sings her royal heart out in a tuneful paean to her about-to-be-lost adolescence, King’s Quest VII exudes Disney-like quality from each of its cel-animated poses.

Every frame is beautiful, every line is neat and pert, the camera soars and glides, and the notes of the musical score tinkle out in bounding effervescence like the fizz out of a bottle of soda pop. This is the Disney of The Little Mermaid or Beauty and the Beast, or Aladdin, if you deduct that film’s adult-targeted sense of irony. It’s the Disney of The Sword in the Stone and of Alice in Wonderland, light and fluffy as a soufflé. It’s not the Disney of Bambi or Snow White; here even the menaces are adorable bits of whimsy. If the villains ever frighten, it’s only for a brief time, and then everyone gets together again for one more song.

It matters not at all that the game is from Sierra rather than Disney. It is true to the Disney spirit.

Along with the mouth-watering new look, the game showed some welcome design evolution over Roberta Williams’s earlier work. Four years after LucasArts’s The Secret of Monkey Island had pointed the way, King’s Quest VII finally managed to free itself from the countless hidden dead ends that had always made playing a Roberta Williams game feel like playing make-believe with a sadist. Player deaths, on the other hand, were still copious, and still so unclued as to be essentially random, but were now at least relatively painless. Rather than expecting you to save every five minutes, the game was now kind enough to return you to the point you were at before you were so foolish as to look at the wrong thing or dilly-dally in the wrong room a second too long. In fact, save files as such disappeared altogether; exiting the game now automatically bookmarked your progress.

These changes all existed in the name of making the game more welcoming to brand new players, out of the hope that they could be convinced to give it a try despite the ominous Roman numeral after its name. To further emphasize that this was a kinder, gentler King’s Quest, it used a radically simplified interface built around a one-click-does-it-all mouse cursor. More oddly, Sierra made it possible to play any of its chapters at any time, meaning you could start with the climax and work backward to the prologue if you were so inclined. (The real point of this feature, of course, was to let you watch each chapter’s opening movie without having to get your hands dirty with the actual game, if you happened to be one of the many people who typically bought each new King’s Quest as a tech demo for their latest computer.)

But alas, in other ways this latest entry really was just another King’s Quest. The writing from Roberta Williams and Lorelei Shannon, her latest apprentice co-designer, was the usual scattershot blend of fairy-tale and pop-culture ephemera, lacking sufficient wit or imagination to be all that compelling even as pastiche, while the puzzle design was made less infuriating than usual only by the lack of dead-player-walking situations. Both the writing and the puzzles got noticeably worse as the game wore on, evidence perhaps of a lead designer who was feeling increasingly bored with her big series, and was in fact already working on her next, very different game. All of this was doubly disappointing coming on the heels of King’s Quest VI, a game which had seemed to herald a series that was at last beginning to take its craft a bit more seriously. Even the much-vaunted look of King’s Quest VII, although impressive in its individual parts, made for a rather discordant jumble when taken in the aggregate, being the work of so many different teams of animators.

Nevertheless, King’s Quest VII sold very well upon its release in November of 1994, as games in the series always did. Meanwhile Dynamix, the most consistent of Sierra’s subsidiary studios, delivered solid performers in the non-adventure games Aces of the Deep, Front Page Sports: Football ‘Pro 95, and Metaltech: EarthSiege. Most of all, though, it was the ImagiNation windfall that turned what would otherwise have been an ugly year into one that actually looked pretty good on the bottom line: $83.4 million in revenues, up from $59.5 million in 1993, with an accompanying $12 million profit, in contrast to an $8.6 million loss the previous year. Now it was up to the new product strategy to keep the party going in 1995.

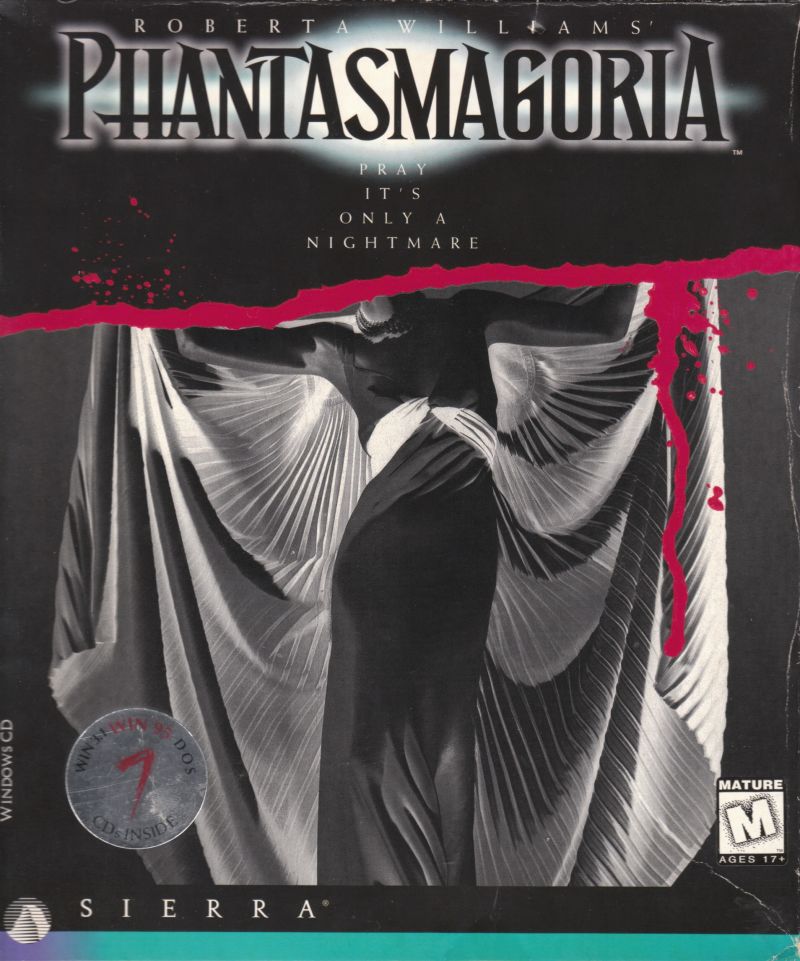

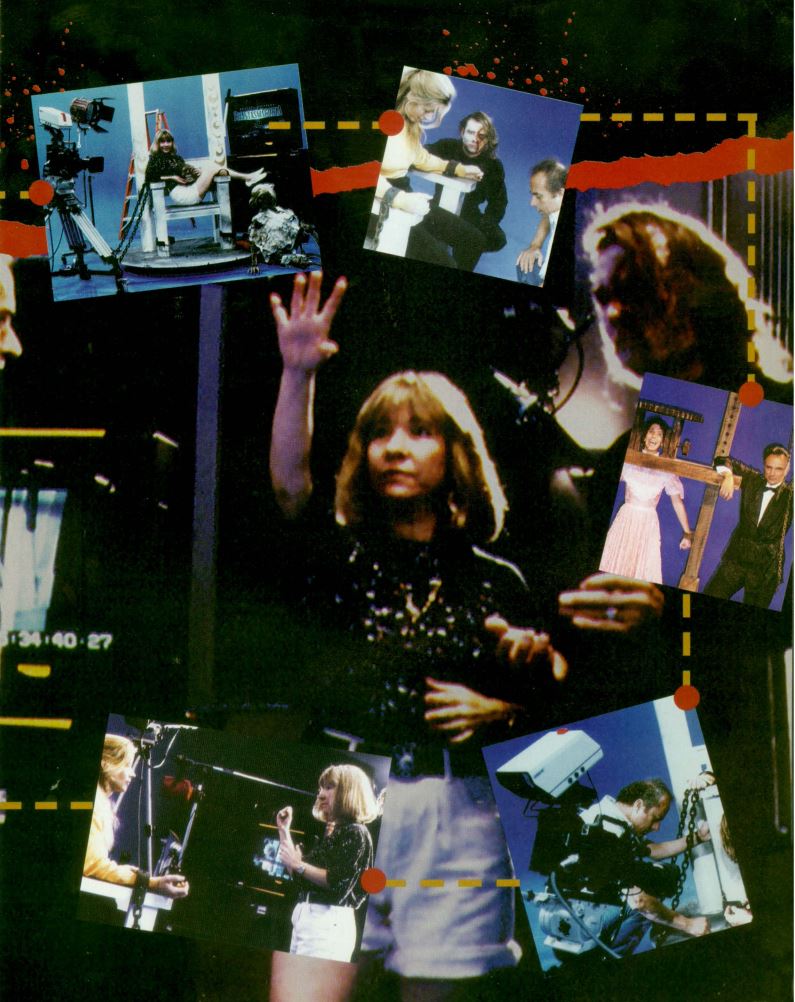

The first big test of that strategy was to be the game that Roberta Williams had been working on concurrently with King’s Quest VII. Phantasmagoria would take full advantage of the Oakhurst sound stage Sierra had just built. It was to be a play against type worthy of any pop diva: Roberta, the family-friendly “queen of adventure gaming,” was going dark and sexy. “With Phantasmagoria,” wrote Sierra’s marketers, “Roberta Williams has created a superbly written interactive story, fraught with horror and suspense, and totally in the player’s control at all times.” Bill Crow, the mastermind of Sierra’s new sound stage, believed that “Phantasmagoria is going to open the market to a much broader audience of game players. We’re now starting to deliver an audiovisual experience that’s much closer to what the average consumer can relate to.” With Phantasmagoria, in other words, computer games were about to burst out of their nerdy ghetto to become sophisticated entertainments for discerning adults.

How times do change. Today Phantasmagoria is more or less a laughingstock, a tidy microcosm of everything that was wrong with the full-motion-video era of adventure games. In truth, some of its bad rap is a bit exaggerated; it’s not really any worse than dozens of other similarly dated productions of the mid-1990s. Certainly plenty of other games had equally cheesy acting, equally clueless writing, and equally trivial gameplay. Phantasmagoria‘s modern reputation for hilarious ineptitude stems to a large extent from its mainstream prominence in its heyday. The wave of hype that Sierra unleashed, much of it issuing from the mouth of Roberta herself, is catnip for snarky reviewers like yours truly, who can’t help but throw it all back in her face. “I want to explore games with a lot of substance and deep emotions,” Roberta said. But Phantasmagoria is so very, very much not that kind of game. If you squint just right, you can see what she was trying to create: a game of claustrophobic psychological horror, an interactive version of The Shining. But alas, nobody involved had the chops to pull it off.

Phantasmagoria revolves around a couple of artsy newlyweds named Adrienne and Don, a novelist and a photographer respectively. As the story begins, they’ve just moved into a rambling old mansion on a sparsely inhabited island off the coast of New England. They’re the first people to attempt to live in the house, we soon learn, in almost a century. The last person to do so before them was a strange stage magician named Carno the Magnificent, who went through pretty young wives at a prodigious rate — all of them abruptly disappearing from the island, never to be seen again. In the end, Carno himself disappeared, and that was that for the house until our heroes turn up. It comes as a surprise to absolutely no one except them when the place turns out to be haunted by a malevolent spirit. It quickly begins to take over the mind of Don, leaving Adrienne, the character the player controls, to try to sort out the mystery before her husband murders her like Carno killed all of his wives.

Somewhat surprisingly in light of Sierra’s mass-market aspirations, they never attempted to hire “name” actors for Phantasmagoria in the way that Origin Systems was doing at the time for the Wing Commander franchise. The role of Adrienne went to Victoria Morsell, whom Sierra rather ambitiously described as a “film, TV, and theater star,” having apparently confused bit parts with starring ones. Still, she does a decent job within the awkward constraints of her task. David Homb in the role of Don, on the other hand, is just awful; his wooden performance comes off as more creepy before the horror starts, when he’s trying to play a loving husband and failing at it abjectly, than it does after his head starts metaphorically spinning around. The rest of the cast is a similarly mixed bag.

Sierra hired a director named Peter Maris, with a long run of schlocky ultra-low-budget films behind him, for a shoot that wound up taking fully four months. Even given that his oeuvre wasn’t exactly of Oscar caliber, his complete disregard for pacing is bizarre. Phantasmagoria‘s seven CDs — yes, seven — are filled with interminable sequences where Adrienne disassembles a brick chimney piece by piece, or breaks through a wooden door board by board, or applies her morning makeup layer by agonizing layer. Indeed, Adrienne insists on stopping and preening herself at each of the many mirrors in the house throughout the game, and we’re forced to watch and wait while she does so, hoping against hope that something interesting might happen this time around. (For all of Roberta Williams’s status as a female pioneer in a male-dominated industry, her games’ view of gender isn’t always the most progressive.) All of this, combined with the clumsy, overly wordy script, makes the game seem much longer than the few hours it actually takes to play. There’s a (bad) 90-minute horror flick worth of plot-advancing footage here at the best; Sierra could easily have ditched three of the seven CDs without losing much at all.

The much-vaunted “adult” content is rather less than it’s cracked up to be. The opening movie includes the least sexy sex scene in the history of media. Ken Williams says that it was originally to have shown Adrienne topless, but Sierra lost their nerve in the end: “When it came time to release the game, we edited it to only show some side boob.” Given how weird and awkward it already is, we can only be thankful for their last-minute fit of prudishness.

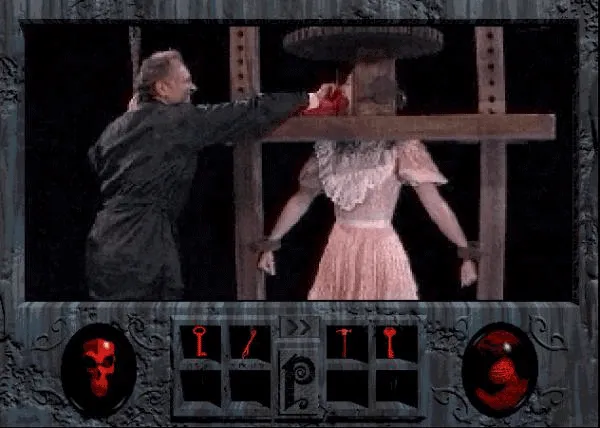

Nor is the game remotely scary, although it does get gruesome — a very different quality — from time to time. These sequences come when Adrienne is visited by visions of the murders that took place long ago in the different rooms of the house, or, in the latter stages of the game, when she herself meets an unfortunate end thanks to a failure on the player’s part. For better or for worse, the methods of murder might just be the most creatively inspired parts of the game: Carno kills one wife by sticking a funnel into her mouth and stuffing disgusting offal down her throat, another by shackling her into a machine that twists her head around until her neck snaps, while Adrienne can get her head sliced in two by an axe blade or her face literally ripped off by a demon. These scenes are certainly gross and shocking in their way, but it’s all strictly B-movie-slasher fare — Friday the 13th Part V rather than the Shining vibe Roberta was going for.

The scene which prompts by far the most discussion today takes place out of the blue one morning, when Don creeps up behind Adrienne at her bedroom mirror and proceeds to… well, to rape her. Needless to say, this is a disturbing place for even an adults-only game to go. Roberta Williams is hopelessly out of her writerly depth here; in contemporary interviews, she seems utterly oblivious to the real trauma of rape, describing the scene as nothing more than a plot device to show Don’s descent into evil. Its one saving grace is the fact that no one involved is up to the task of making the rape seem remotely realistic; Don humps and thrusts a bit without ever actually taking his boxer shorts off, and that’s that. (One can only hope that Sierra didn’t shoot a more explicit version of this scene…) Afterward Adrienne, rather in contrast to Roberta’s stated desire to explore “deep emotions,” just cleans herself up and gets on with her day, apparently none the worse for wear. Even amidst the more lackadaisical sexual politics of 1995, the scene prompted considerable discussion and a measure of public outrage here and there. Australia’s Office of Film and Literature Classification refused to accept the game because of it, with the result that it was effectively banned from sale in that country.

So much for Phantasmagoria the movie. In terms of gameplay, it isn’t up to all that much at all. Its reliance on canned snippets of static video dramatically limits the scope of its interactivity, while its determination to be as accessible as possible means that all of its puzzles are broadly obvious; a version of that tired old adventure saw, the locked door with a key in the keyhole on the other side and a handy nail and newspaper, is about as complicated as things ever get. The simplified interface from King’s Quest VII makes a return, it’s once again possible to play the chapters in any order you choose, and bookmarks once more replace save files in the game’s terminology, although it is at least possible to make your own bookmarks whenever you like now.

In a way, all of this is a blessing: it lets you power right on through Phantasmagoria, laughing at it all the while, without getting hung up on the design flaws that dog most of Roberta Williams’s games. I’m not generally a fan of high camp, but even I could probably enjoy Phantasmagoria with the right group of friends. If ever a game was ripe for the Mystery Science Theater 3000 treatment, it’s this one.

Note the ESRB rating at the bottom right of the Phantasmagoria box. In the face of the internecine split over rating systems among computer-game publishers, Sierra generally backed the ESRB over its rival the RSAC. (The much more extreme sequel-in-name-only Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle of Flesh would go with the RSAC in order to avoid the ESRB’s dreaded “Adults Only” rating, which most retailers refused to touch.)

Objects in your inventory can be viewed as rotatable 3D models, a capability that debuted in King’s Quest VII. Indeed, Phantasmagoria‘s environments were all built using 3D-modeling software rather than being hand-drawn pixel art. This is the only way Sierra could possibly have included more than 1000 different views in the game, as their marketers proudly told anyone who would listen; the typical old-style Sierra adventure had less than 100. But the new approach didn’t lead to increased environmental interactivity — rather the opposite, I’m afraid.

Adrienne with psycho-hubby Don. Both wear the same clothes for all seven days of the game, a fact that has prompted much joking over the years. This was judged necessary so that the developers could mix and match video sequences as needed. The outfit that Adrienne wears is actually the one that Victoria Morsell, the actress who portrayed her, just happened to turn up in on the first day of filming. “By the time the filming for Phantasmagoria was complete,” wrote Sierra in their customer newsletter, “duct tape, patches, and prayers were all that held Tori’s pants together. She had worn them to the set every single day of the fifteen weeks of filming.”

One of Carno’s ingenious execution devices. Sierra had these props built by local Oakhurst craftsmen, prompting much discussion in the town about just what it was they were up to inside the building that housed their sound stage.

The real horrors of Phantasmagoria are Harriet and her son Cyrus, a pair of bumpkin ingrates who are meant to serve as comic relief. They’re exactly as unfunny as this screenshot looks.

But that, of course, is now. When it was released in the summer of 1995, accompanied by the most lavish marketing campaign Sierra had ever sprung for, Phantasmagoria was hailed as the necessary future of gaming — and not just by Sierra’s own marketers. All of the drawbacks of its technical approach, which would have still been present even with better writing, designing, acting, and directing, were overlooked by industry scribes eager to see the fusion of Silicon Valley and Hollywood. “For horror fans,” wrote Computer Gaming World, “Phantasmagoria is a signal event, one of the most powerful titles ever released in the genre, and easily the most single-mindedly horrific.” In a fit of exuberance, Roberta Williams let slip her dream of becoming “the Steven Spielberg of interactivity.” Thus she must have reveled most of all in the mainstream-press coverage. USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, and Billboard all gave the game positive reviews; “Hotly awaited and, well, just hot, Phantasmagoria lives up to the advance billing,” wrote the last. Notices like these easily made up for the refusal of some squeamish retailers, among them the national chain Comp USA, to stock the game at all.

Every article was sure to mention the game’s budget of fully $4 million, an absolutely astronomical sum by the standards of the time, and one which Sierra too trumpeted for all it was worth in their advertising. In truth, much of that money had gone into the building of the Oakhurst sound stage that Sierra planned to use for many more games, but no one was going to let such details get in the way of a headline about a $4 million computer game. Phantasmagoria became a massive hit; its sales soared past the magic mark of 1 million units and just kept right on going. It was a perfect game to take home with a shiny new computer, the perfect way to show your friends and neighbors what your new wundermachine could do. The window of time in which a game like this could have success on a scale like this was to prove sharply limited, but Phantasmagoria managed to slip through behind Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, The 7th Guest, and Myst just before said window slammed shut. It would prove the last such sparkling success among its peculiar species of game.

But what a success it was while it lasted. Phantasmagoria still stands as the best-selling game ever released by an independent Sierra. Small wonder that Ken and Roberta Williams both remember it so fondly today. Rather than a laughingstock, they remember Phantasmagoria as a mainstream-press darling and chart-topping hit, and love it for that. Thus Ken continues to describe it as “awesome,” while Roberta still names it as her favorite of all the games she made. It was all too easy in 1995 to believe that Phantasmagoria really was the future of gaming writ large.

The Oakhurst folks finished three other adventure games that year, with more mixed commercial results. Space Quest 6, which was made with a lot of the traditional Sierra style but without a lot of enthusiasm from upper management, validated the latter’s skepticism when it failed to sell all that well, signifying the end of that series. Torin’s Passage, a workmanlike fantasy adventure in the King’s Quest mold by Al Lowe of Leisure Suit Larry fame, was another mediocre performer, one whose reason for existing at all at this juncture was a little hard to determine. Finally, the second of the new generation of Sierra adventures, built like Phantasmagoria around filmed actors, was The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery. I’ll return to it in my next article.

Yet Oakhurst was no longer the be all, end all of Sierra. In the new corporate order envisioned by Ken Williams and Mike Brochu, the adventure games that came out of Oakhurst were to be only a single piece of the overall Sierra puzzle. They planned to build an empire from Bellevue that would cover all of the bases in consumer-oriented software. Already over the course of the previous half-decade, Sierra had acquired the Oregon-based jack-of-all-trades games studio Dynamix, the Delaware-based educational-software specialist Bright Star, and the artsy French games studio Coktel Vision. Now, in the first year after Brochu’s hiring, they made no fewer than six more significant acquisitions: the Texas-based Arion Software, maker of the recipe-tracking package MasterCook; the Washington-based Green Thumb Software, maker of Land Designer and other tools for gardeners; the British Impressions Software, maker of a diverse lineup of strategy games; the Massachusetts-based Papyrus Design Group, a specialist in auto-racing simulations; the Washington-based Pixellite Group, the maker of Print Artist, a software package for creating signs and banners; and the Utah-based Headgate Studios, a specialist in golf simulations.

Of all the other products Sierra released in 1995, the one that came closest to matching Phantasmagoria‘s success came from good old reliable Dynamix. “I was in a high-level meeting,” remembers Dynamix’s founder Jeff Tunnell, “and the sales manager for all of Sierra said, ‘These fishing games are selling in Japan on the Nintendo.’ Everybody started laughing. But I said, ‘I’ll do one.'” Like Phantasmagoria, Trophy Bass was consciously designed for a different demographic than the typical computer game; it looked more at home on the shelves of Walmart than Electronics Boutique or Software Etc. It shocked everybody by outselling all other Sierra games in 1995, with the exception only of Roberta Williams’s big adventure, becoming in the process the best-selling game that Dynamix ever had or ever would make. Thanks to it, the later 1990s would see a flood of other fishing and hunting games, most of them executed with less love than Trophy Bass. Hardcore computer gamers scoffed at these simplistic knockoff titles and the supposed simple-minded rednecks who played them, but they sold and sold and sold.

Along with Phantasmagoria and other Sierra products like The Incredible Machine, Trophy Bass provided proof positive that there were any number of new customer bases out there just waiting to be tapped, made up of people who were looking for something a bit less demanding of their time and energy than the typical computer game for the hardcore, with themes other than the nerdy staples of science fiction, fantasy, and military simulations. Whatever his faults and mistakes — you know, those ones which I haven’t hesitated to describe at copious length in these articles — Ken Williams realized earlier than most that these people were out there, and never stopped trying to reach them, even as he also navigated the computer-game market as it was currently constituted. For this, he deserves enormous credit.

As Sierra came out of 1995, he had good reason to feel pleased with himself. Revenues had nearly doubled over those of the previous year, to $158.1 million, and even all of the acquisitions couldn’t prevent the company from clearing over $16 million in profits. With Electronic Arts, the only publisher of consumer software with equal size and clout, now investing more and more heavily in console games, Sierra seemed to stand on the verge of complete dominance of the exploding marketplace for home-computer software. Ken’s longstanding dream of selling software to everyone was so close to fruition that he could taste it. And as for Roberta: her own dream of becoming the Steven Spielberg of interactivity seemed less and less far-fetched each day.

If you had told the pair that Roberta would never get the chance to make another point-and-click adventure game, or that the Oakhurst sound stage would be written off as a colossal blind alley and decommissioned within the next few years, or that neither of them would still be working for Sierra by that point, or that Sierra’s Oakhurst branch as a whole would be shuttered well before the millennium… well, they would presumably have been surprised, to say the least.

(Sources: the books Phantasmagoria: The Official Player’s Guide by Lorelei Shannon and Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line by Ken Williams, Computer Gaming World of February 1995 and November 1995, Los Angeles Times of November 14 1995, Sierra’s customer newsletter InterAction of Fall 1994, Holiday 1994, Spring 1995, and Holiday 1995; press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Video sources include a vintage making-of-Phantasmagoria video and Matt Chat 201. Other online sources include “How Sierra was Captured, Then Killed, by a Massive Accounting Fraud” by Duncan Fyfe at Vice, Sierra’s SEC filing for 1996, Anthony Larme’s Phantasmagoria fan site, the Adventure Classic Gaming interview with Roberta Williams, Ken Williams’s comments in a Sierra Gamers discussion of King’s Quest opening movies, and the current MasterCook website. And my thanks go to Corey Cole, who took the time to answer some questions about this period of Sierra’s history from his perspective as a developer there.)

Zack

August 6, 2021 at 4:58 pm

Damn, I didn’t know Sierra had such a rich history before they started making the city-builders games I know them for. I guess it’s still a long way before getting there…

Jimmy Maher

August 6, 2021 at 5:08 pm

Those games were made by Impressions. Caesar and Caesar II had already been released — both published by Sierra — before Sierra acquired the studio. Will indeed cover them at some point, when we get to the later installments that are a bit more playable by modern standards. I’m particularly partial to Pharaoh.

Zack

August 6, 2021 at 9:16 pm

I played all of them, starting with Emperor. Seeing you were talking about Sierra and all, I got worried for a second seeing you didn’t mention those games at all. But I’m glad to hear we’ll talk about it further down the line.

Personally I’m partial to the latest one, Emperor, because A) It was the first one I played and B) The French version (I’m French) had really memorable voice-overs and writing, I still can quote most of them to this day. I got on the others one later, and these days yeah, Pharaoh is probably the one that’s most memorable, the one with very striking vision (also the only one with an expansion pack, I think.)

Phil B.

August 7, 2021 at 2:52 pm

Zeus also has an expansion pack (Poseidon). Pharoah and Zeus are definitely my two favorite in that series.

Not Fenimore

August 8, 2021 at 1:57 pm

Caesar III was the first game I ever personally bought; Emperor is still my favorite city-builder (just nice quality of life inprovements). Even after literal years of Mr Maher’s articles, my brain, deep down, still thinks of Sierra as a competitor to Maxis (“the other most important computer game maker”).

Leo Vellés

August 6, 2021 at 5:13 pm

“hoping against hope that something interesting might happen this around”.

I’m not sure, but i found a little off that final “around”. You meant “round”?

Jimmy Maher

August 6, 2021 at 6:58 pm

I dropped a word, actually. Thanks!

Martin

August 6, 2021 at 5:49 pm

So you are on a desert island and can only have one game, Phantasmagoria or 7th Guest. Which do you pick? No, “I wouldn’t pick either” answers allowed. I’m really trying to ask, which is better, or worst?

Jimmy Maher

August 6, 2021 at 7:04 pm

7th Guest for me. I suppose the set-piece puzzles might have some replay value if I get really bored — although in all honesty, I could probably invent more exciting games with rocks and sand, given sufficient time — and a lack of gratuitous rape scenes generally boosts a game in this critic’s estimation.

Ross

August 6, 2021 at 10:13 pm

There’s a tragic irony here that you’ve cited a criteria that might lead you a reversal had you been offered the respective sequels.

Alex Smith

August 7, 2021 at 5:28 pm

In fairness, I don’t think the rape scene was gratuitous so much as poorly executed (which is a general problem with the entire game). It’s meant to contrast with their earlier tender lovemaking scene to illustrate how much the possession is changing Don. What makes it fail utterly, and yes admittedly even feel a bit gratuitous, is the reason you articulate in the body that there is zero emotional fallout from the scene. I do think if it were handled appropriately it would have served both the plot and the characters, but obviously it was not.

Lasse

August 6, 2021 at 6:06 pm

Typo: “Robera Williams’s earlier work.”

Jimmy Maher

August 6, 2021 at 6:58 pm

Thanks!

Sean Barrett

August 6, 2021 at 7:15 pm

I can’t figure out the reason for this article’s title. Is it just meant as as a fake-out with the actual meaning being “Making Sierra Pay Off”?

Jimmy Maher

August 6, 2021 at 7:27 pm

The same phrase could mean to make Sierra pay in the mob-movie sense, or to make Sierra pay (off). I went back and forth on it, but decided I liked it better without the dangling preposition. I could be convinced otherwise, however, if others find it weird or confusing.

Michael

August 6, 2021 at 10:49 pm

I’d leave it as written. What you mean is “Making Sierra Profitable,” but that’s a terrible title, and “Making Sierra Pay Off” definitely evokes images of a guy named Nunzio with a baseball bat.

DZ-Jay

May 2, 2023 at 7:15 pm

So does “Making Sierra Pay,” which game me the impression that the story was going to be about a series of lawsuits to bring upon the comeuppance of Ken & Roberta Williams.

As it stands, the title is ambiguous at best, misleading at worst.

Perhaps something less clever and more prosaic would work better, like, “Sierra’s Big Payday!” I don’t know.

dZ.

Ross

May 3, 2023 at 12:10 am

See also the seminal but distractingly titled waterfowl husbandry book “Ducks, and how to make them pay”

Andrew Nenakhov

August 6, 2021 at 8:31 pm

Interestingly, that morning ‘rape’ scene was shown only when loading Chapter 4 from Chapter 3. If you wanted to just start Chapter 4, it just started with Adrienne tying shoelaces on her sneakers.

California Tax Payer

August 17, 2021 at 2:44 pm

In the beta, it shows the scene if you start a new game on chapter 4.

Another other difference I see is that there are no captions on the intro videos of (at least) chapter 1. It didn’t seem to let me use the poker on the fireplace in the beta.

Leo Vellés

August 6, 2021 at 9:23 pm

One minor typo. The french studio name is Cocktel Vision, not Visions

Jimmy Maher

August 7, 2021 at 7:40 am

Thanks!

Michael

August 6, 2021 at 9:40 pm

“So, Sierra’ new Bellevue management team”

= Sierra’s

Jimmy Maher

August 7, 2021 at 7:41 am

Thanks!

Jonathan O

August 6, 2021 at 10:14 pm

Typo alert: “pop-culture ephmera” -> “pop-culture ephemera”

Jimmy Maher

August 7, 2021 at 7:44 am

Thanks!

Owen C.

August 7, 2021 at 1:40 am

Among other things, you could say Phantasmagoria wasted a lot of effort and then-precious CD space filming tons of clips of a live actor going through the mundane motions of a Sierra character like walking between every room and interacting with every object in the game. Stuff which was easy to implement in their older games with a sprite moving around the screen but required a ton of effort and space that could have been better spent elsewhere when switching to live action. There’s definitely a reason why most other FMV adventure games of the period chose not to go down this route and instead chose to adopt the first-person perspective adopted by Myst, The 7th Guest and others where they don’t have to film the player character performing every action in the game.

Eric Nyman

August 7, 2021 at 3:14 am

The idea that no “A” level talent would want to live in Oakhurst is strange to me. Yes, it’s a small isolated town, but it sits near Yosemite, Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks in close proximity to the Sierra Nevada, the tallest mountains in the contiguous USA (from which the company derived its name and logo). Surely they could have found an outdoorsy type who would consider that paradise.

Though to be fair, Bellevue also has world class mountain and national park access, as well as an ocean nearby and a major city. So on balance it’s a more attractive destination for most.

An acquaintance of mine worked for Dynamix in Eugene, OR and prior to that at the Oakhurst office for Sierra (not as a programmer however–she was in HR, I believe). She did not find the Williamses to be personable or even taking much notice of what they considered lower level employees, but on balance she found it to be a pleasant place to work.

Jimmy Maher

August 7, 2021 at 7:50 am

Having become an inveterate hiker since reaching middle age, I’d love to live there myself. But it was one more quality to look for in what was already a fairly small pool of people Ken Williams considered to be qualified.

In the end, Ken dreamed of building a software empire to rival even Microsoft in its way, and didn’t believe he could do so from Oakhurst. And this was a fair assessment, on the whole. Just the lack of proximity to a major international airport was crippling. After all, Microsoft moved from Albuquerque — a much larger city — to Seattle for similar reasons.

Nate

August 8, 2021 at 12:58 am

I grew up not far from there and Oakhurst of the 80’s and early 90’s was still pretty remote. There were no other software companies. The closest analog I can think of is Atari’s Grass Valley center.

Despite the nearby beauty, it was just too isolated from other opportunities available nearby in Silicon Valley.

Steve Nicholson

August 8, 2021 at 8:10 am

I’ve lived in in Nevada City, which borders Grass Valley, for 21 years and have worked in Grass Valley for most of that time. I didn’t know until now that the Atari 2600 was developed there. I’m amazed that this isn’t more well-known in the community. Mostly we hear about Grass Valley Group who made broadcast video equipment and spawned a slew of spin-offs like Telestream and AJA Video.

Peter Orvetti

August 7, 2021 at 3:17 pm

That’s a funny anecdote about Victoria Morsell’s wardrobe, given that one of the jokes I see about the game is how unrealistically high her belt/waistline is.

The guy who plays Don has his game image as his social media avatar. He seems to have a sort of wry appreciation of his brief fame, like the little girl from “Manos: Hands of Fate”.

Emily Bowman

August 17, 2021 at 10:04 pm

Anyone who says her waistline was unrealistically high must have the distinct pleasure of not remembering the mid-90’s. That fad’s come back around a couple times, but thankfully never has much staying power.

Lisa H.

August 18, 2021 at 12:22 am

Trufax!

Joshua Barrett

August 8, 2021 at 12:45 am

While it’s also not a good game, I confess to finding Phantasmagoria 2 somewhat more compelling than the first. No, I don’t have an excuse. It’s just… well, it’s not exactly original, but it’s considerably *more original* than the first.

Ross

August 8, 2021 at 2:46 am

It was certainly more of a Noble Failure than the first. Properly experimental in ways that seem to have influenced the handful of 21st-century FMV efforts. The first game was, for all its oddities, sort of a “safe” approach to an FMV horror game – a very standard and traditional Spooky House story with broadly gothic sensibilities with gameplay and puzzles that was a bit clumsy but for the most part basically just a very straight adaptation of Sierra’s house style to the limitations of live action.

DZ-Jay

May 2, 2023 at 7:33 pm

I had a similar impression, although in my view it is not a positive thing. I found Phantasmagoria to be an engaging and interesting game, if goofy at times, and ham-fisted in its general aesthetic.

Phantasmagoria 2 struck me as attempting to be shocking for its own sake, with voyeuristic, fetishist, semi-pornographic tendencies. The game itself, and it’s storyline, was much more vapid than even the derivative Phantasmagoria; and offered nothing more than an excuse to show some skin a kink.

I’ve tried playing both games over the years, and I’ve always managed to finish the first one and enjoy it for what it is; while the sequel always causes me to lose interest less than half-way through, as it devolves more and more into a mess of weirdly composed scenes and incoherent sequences, presumably intended to show me how “very subversive” its story really is.

Even with a walkthrough, I end up leaving the game before the end.

dZ.

Aaron A. Reed

August 8, 2021 at 6:25 pm

I have a massive soft spot for Phantasmagoria 2 because as a young gay man (I think I was 16 when it came out), it was the first computer game I ever played with queer characters– more than one, even!– who weren’t just there as one-off jokes. They were major characters and they were taken seriously by the other characters as people, not just stand-ins for their sexuality. That was so hugely important to me at the time; not just encountering it at all, but also through playing the game with my friends (who I wasn’t yet out to) and seeing them accept that part of those characters non-judgmentally and not make jokes about it… that experience was a big factor in my ability to come out to my friend group a few months later.

Whatever its other faults, I’ll always love Phantasmagoria 2 and Lorelei Shannon et al for that non-token representation, years (decades, really) before most other game companies would dare to put characters like that front and center.

Jay Friday

August 8, 2021 at 8:53 am

I remain a huge fan of the Papyrus racing simulation games. They were absolutely the cream of the crop in that particular genre, only remotely rivalled by Geoff Crammond’s Formula 1 games. Strangely enough, in a genre that thrives on technical sophistication, they also remain very playable to this day. I still like to play IndyCar Racing II or one of the NASCAR games from time to time, for instance. And, of course, the monumental Grand Prix Legends from 1998, which still retains an active community.

They were always maybe a little too hardcore to find mainstream appeal, but gosh, were they good. Huge get for Sierra back then, definitely. And when their parent company pulled Papyrus into the abyss with them in the mid 2000s, they became iRacing, which to this day is a standard in hardcore simulation racing. Incidentally, this is where they finally lost me – I just can’t afford to put in the time to actually play that game the way it wants to be played.

Greg

August 8, 2021 at 1:12 pm

There’s a popular retro gaming YouTuber who goes by MetalJesusRocks that worked at Sierra in Bellevue in this period. I’m not affiliated with dude, but check out “We Worked at Sierra! – The Rise, Fall & Scandal of Sierra On-Line”. His buddy he does that video with has an incredible archive of old interviews he did for an internet radio show on Worldstream. “Slow Death of Publisher Sierra – Lost Interview During Layoffs 1999” has him talking with the developers of a Babylon 5 game and a Lord of the Rings game, the day of the layoffs. Sadly, the majority of MJR’s audience isn’t quite as interested in these rare time capsules so they’ve only uploaded a few, which is a bummer because apparently he’s got an interview with Jane Jensen from around this time.

Anyways, looking forward to the GK2 article! Kriminalkommissar Lieber…is he here?

Greg

August 8, 2021 at 1:18 pm

Forgot to add that I thought of all of this because in the layoff interview, the devs he talks with sarcastically refer to the fishing games. Have a good one!

Fuck David Cage

August 8, 2021 at 10:06 pm

Sierra was my favorite adventure game company, but it died of cancer, screaming and begging for death. Phantasmagoria was dogshit, the worst example of the awful F.M.V. bubble that nearly destroyed video games: Nothing happens until the last ten minutes, the gameplay consists of boring chores and stupid puzzles, the writing is the worst video game writing because David Cage’s work and Life is Strange are movies, and it has no tension or horror, just cheap, stereotypical mid ’90s attempts at shock. I thought it was one of the worst games ever at the time, and even after playing Ultima 8, Universal Combat, To The Moon, Gemini Rue, NES Rambo and watching playthroughs of The Last of Us 2, Cyberpunk 2077, XIII remake and Ride to Hell Retribution I still stand by it. Gabriel Knight 2, sequel to my favorite adventure game suffered from the same problems and was a horror set in the bright sunlight in a quaint, charming city. Phantasmagoria 2 and Gabriel Knight 3 were marginally better and things actually happened in them, but still terrible. Space Quest 6 ruined a great series in the same way as Phantasmagoria and the Gabriel Knight sequels: While it was not as bad, it had very simplistic puzzles, very little humor, a lot of filler and many contradictions of the previous games. King’s Quest 7 was almost a tolerable adventure game, but there were many bugs that could stop your progress and force you to skip stages, as I had to a couple of times, and the writing was childish and awkward.

Fuck David Cage

August 8, 2021 at 10:14 pm

I recommend that anyone who hates the final years of Sierra as much as I check out the perfect fanmade Sierra games, Space Quest Incinerations and Vohaul Strikes Back. They give perfect endings to Sierra’s best series, particularly if you get all the points in Incinerations and have hilarious humor, great puzzles and deaths and hilarious responses to every possible action.

I also recommend Mage’s Initiation: Reign of the Elements and Al Emmo and The Lost Dutchman’s Mine, inspired by Sierra classics. Mage’s Initiation is a Quest for glory tribute with all the humor and style you would expect from Sierra. It could use more puzzles, but at least unlike Hero U it actually has some puzzles. Al Emmo does the same for Leisure Suit Larry and Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist and also has a lot of complex puzzles.

Arthur

August 8, 2021 at 10:37 pm

On King’s Quest 7, which I covered my own thoughts on here, I think it really suffered from having so many hands handling the animation. Apparently, the first studio to accept work on it was a Russian outfit who claimed they could handle the whole thing, then couldn’t, hence farming bits of work out to other places – some of whom had never animated for videogames before. I thought the animation was kind of disjointed – and in particular, some weird prioritisation was occurring, so some really important plot-critical bits were animated in a fairly rudimentary fashion whilst some parts which were just not that important seemed to have been lavished with attention.

On Phantasmagoria, which I reviewed here, I thought the rape scene was handled well in the moment in the sense that it did at least seem to acknowledge that something bad and abusive was happening here, but agree that it kind of fails to follow through on the emotional impact of it. (It also sets up a “he’s only abusive because he’s possessed” angle, which I feel plays into unhelpful “he’s abusive but if I love him enough I can change him and he’ll stop” tropes.)

In terms of its laughable aspects there’s two things which jump to mind for me:

– Adrienne finds two people literally living in the barn and is… fine with it. She’s not at all worried or concerned or even suspicious, and then hires them as household staff on the spot, because of course when people have invaded your home the first thing you do is give them unlimited access to the entire rest of your home.

– The backgrounds. People giggle at the FMV and the acting and the plot and so on, and for the most part they are right to, but I’ve always found the backgrounds in the game to be jarring. It’s rather evident that the actors think they are in, if not a Stephen King movie, then at least a B-grade slasher, but the animators doing the backgrounds were going for a campy Hammer Horror aesthetic. It’s an utter mismatch.

I agree with the people upthread that Phantasmagoria 2 is actually kind of better than the first game and has more redeeming features. Not enough to counterbalance its flaws – it’s not a good game which has a few stumbles, it’s a bad game with a lot of heart and which occasionally pulls its socks up and has periods of being actually pretty interesting. But enough to make it perhaps more worth a look back to these days than a lot of the FMV schlock of the era.

Saint Podkayne

August 12, 2021 at 1:41 am

To me the major moment of failure is the entirety of Adrienne and Don’s relationship. They just suck. They are in different marriages from the very beginning before the possession even occurs. I can’t imagine a scenario where I find myself unlocking a secret occult chapel behind a fireplace in a large, creepy house inhabited by only myself and my husband, and my very first reaction isn’t “Huh, this doesn’t look right, hey, husband, you want to come over here to look at this creepy shit for a sec?” and then my husband’s first reaction isn’t “Hold on, I’m coming, what creepy shit?”. Later, after he’s possessed, Adrienne totally fails to be surprised or shocked or upset by any of his terrible behavior. She seems to expect to be treated this way. She does not seem to expect the basic politeness of someone opening a door to talk to her instead of yelling through it. To me the tragedy isn’t even her lack of reaction to the rape, it’s her lack of reaction to the constant contempt and rudeness.

Martin

August 12, 2021 at 3:00 pm

You would be surprised what people make ‘work’ in their relationships. Sounds like yours is holding together but people make far worse act as their norm.

Ok, the fireplace creppy shit isn’t what relationships have to endure – more likely is finding out uncle-grandpa’s final secret is as far as people go in real life. But there are people out there that identify with this way of living, unfortunately.

Adam M

August 9, 2021 at 11:25 am

Thanks for this. I am looking forward to your next and I presume final installment on the Sierra On-Line story.

Lt. Nitpicker

August 13, 2021 at 8:33 pm

But Police Quest would get revamped from a line of adventure games into a line of tactical 3D action games..

The first SWAT game was a hybrid between a tactical game and a conventional Sierra adventure of the period, and the second game didn’t come out until a couple of years later. I would use the phrase slowly in this context.

California Tax Payer

August 15, 2021 at 7:34 pm

I took a tour of the Oakhurst office around 1993. The guide mentioned the move to Washington, which was then unknown to me, and did mention taxes as a reason. They didn’t mention the home-town disadvantage.

The 1994 games KQ7 and Outpost were the only times I ever used Sierra’s money back guarantee — and didn’t feel bad about it. Outpost got a few updates, and KQ7 ended up with a ‘2.0’ release.

I believe the studio set was in the Old Barn building. In any case, the building burned down a few years ago when a wildfire burned through that end of town. I have a 7-CD beta version of Phantas which had some missing video, a rougher version of the video, and lacking most sound, as I recall. It was dated only about two months before completion, so either the game came together very near the end, or they intentionally crippled it. The primary purpose was probably to test out all the DOS SVGA chipset drivers and Windows SVGA and audio drivers; the final product has a pretty extensive tech support document.

In the files:

If you find that you need to send for replacement CD disks,

blah blah blah

blah blah blah

In the letter by Jerry Bowerman, General Manager, Sierra Publishing, June 2, 1995:

“A group of about 40 people at Sierra Publishing here in Oakhurst … Our goal is to produce the most enjoyed game of 1995. … After compositing the blue screen elements … making the movies into AVIs from tape… We didn’t feel the results were of the quality we needed … In addition, we decided to go to an outside sound design house for the foley and sound effects, and the integration of the sound track. So, we captured some scratch movies from VHS [for beta] … Some of them look pretty bad. I apologize for this but rest assured the final movies will be of a quality consistent with Sierra’s products.”

“

Jonathan

December 10, 2021 at 2:31 am

I just wanted to say thanks so much for this informative, entertaining, enlightening, etc etc etc good points… good points… blog.

I’m reading it from the perspective of someone who grew up playing mostly Sierra games in the 80’s to mid 90’s, with absolutely no background in programming or computers in general. You’ve really made topics which are way over my head (somewhat) easier for me to understand, but most importantly completely compelling. Thank you so much.

I totally see your point about a lot of the insane logic and sloppy puzzle design of most of the Sierra games, but for me, the puzzles or endless deaths / dead ends just didn’t matter. I played the games for the characters, the settings and atmosphere, the art (especially the background paintings), the music, and the stories. The puzzles were almost incidental. I used a lot of walkthroughs or persuaded my dad to fax questions to the Sierra hint department because I really just wanted to enjoy these worlds without the hassle of having to figure out what random objects you had to use to advance the plot. I know that flies in the face of good game design, but I suppose my point is, for people like me it just didn’t matter. I loved these games for an entirely different reason, and they’re still near and dear to my heart. To be fair the games with good puzzle design like Quest for Glory are nearer and dearer to my heart than the sloppier ones, but still I was always willing and able to just sort of ignore the puzzles in favor of loving the worlds I got sucked into.

Anyway I just wanted to say thanks and express what it was that drew me to Sierra games from my own perspective. I agree with basically everything you’ve written on here, and yeah good puzzles and design should be integral to making a quality game, but I still loved / love those games so much. I know the puzzles were shit, though ;-)

Kelly

October 6, 2024 at 5:56 am

I too am a classic Sierra fan who made heavy use of walkthroughs and treated/thought of the games (particularly the later ones) more as beautiful, funny and sometimes touching interactive movies or multimedia experiences than puzzles to be solved. And like Jonathan, I appreciate, acknowledge and agree with your perspective, while noting it has very little to do with how I engaged these games. :)

clubside

February 15, 2022 at 5:59 pm

One plural too many:

“Hardcore computers gamers scoffed…”

Jimmy Maher

February 16, 2022 at 4:15 pm

Thanks!

Lisa M Cundy

April 23, 2022 at 3:47 am

I worked for Sierra in Bellevue and loved it! Worked my way up to purchasing assistant before the department was set to move back to Cali after the company sale…I was so sad! And I rocked the front desk before my last promotion with Ken too the Left and Roberta too right! ☺✌ lol and always looking for ya both behind homeplate

TerokNor

December 9, 2022 at 1:27 pm

I was reading/researching about Sierra’s Bellevue days and found this article, excellent as usual. I’m particularly interested in the era when development was done both in Oakhurst and Bellevue. What was done where is not easy to determine, so I’m hoping to learn more in future articles.

Some notes on the additional acquisitions: Bright Star legally might have been a Delaware Corporation, but it was (as already pointed out in The Mortgaging of Sierra Online) based in Bellevue. So I wonder if Bright Star became Sierra’s Bellevue studio? Or did they create a new one and then fold Bright Star into it?

Impressions was originally a UK company, but I was never able to find out for sure if there was a ever UK in-house development, it might have all been done by freelancers. The US studio which I think was largely responsible for the well-acclaimed later city builders was based in Massachusetts.

Hresna

July 1, 2024 at 5:23 pm

It’s funny how the context behind one’s playthrough of a game can end up meaning so much more to the experience and memory of it than the actual game itself, or at least being as impactful.

I have no doubt Phantasmagoria is as mediocre as described here. I would have lacked the discerning palate in my early teen years when I played it in a single evening at a friend’s house. He had bought it close to its release and got lucky at the tiller – it kept ringing in at $20 instead of $60+, so the cashier finally said “okay, for you it’s $20”. So we didn’t feel too badly about how quick we got through it.

The creep-scare of a baby’s crying from the nursery was about the only memorable moment, along with having to watch our head explode repeatedly in the ending sequence. Something about being up way past your bedtime fuelled by colas made that more jarring.

I haven’t revisited the game since, but that playthrough with a buddy at a sleepover is one of my core memories. I’m kindof tempted to revisit it now. Thanks!

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2024 at 12:55 pm

That sounds like a fine memory. And you’re absolutely right that the context in which we encounter games is super important to our relationship with them. That’s something that articles like this one have difficulty accounting for, being only able to examine the naked artifacts themselves.

That said, you might want to think twice about revisiting Phantasmagoria. ;) Sometimes it’s best to let the past be the past…

Adamantyr

April 16, 2025 at 3:29 am

I bought Phantasmagoria back in ’95, still have my CD’s somewhere. No idea if it would still run on Windows 11…

I never finished the game. I found the puzzles trite and weird, the acting awful, and the whole single path forward in every chapter boring. It’s sad to see Victoria’s acting career didn’t last after it. I even thought while playing it “Really? Ken and Roberta made this? This isn’t… good.”