Movies and computer games are my two favorite things. If I weren’t doing one I’d be doing the other.

— Chris Roberts

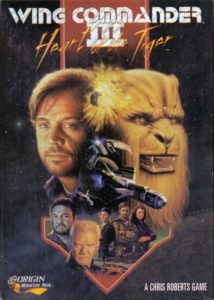

Prior to the release of DOOM in late 1993, Wing Commander I and II and their assorted spinoffs and expansion packs constituted not just the most popular collection of outer-space shoot-em-ups since the heyday of Elite but the most popular computer-gaming franchise of the new decade in any genre.

Upon its release in September of 1990, the first Wing Commander had taken the world by storm by combining spectacular graphics with a secret weapon whose potency surprised even Origin Systems, its Austin, Texas-based developer and publisher: a thin thread of story connected its missions together, being conveyed through the adventure-game style interface that was employed for the scenes taking place on the Tiger’s Claw, the outer-space “aircraft” carrier from which you and your fellow fighter pilots flew in a life-or-death struggle against the Kilrathi, a race of genocidal space cats who regarded humans the same way that Earthbound cats do mice. Having seen what their customers wanted, Origin doubled down on the drama in Wing Commander II, which was released in August of 1991; it told a much more elaborate and ambitious story of betrayal and redemption, complete with plenty of intrigue of both the political and the romantic stripe.

After that, the spinoffs and expansion packs had to carry the franchise’s water for quite some time, while Chris Roberts, its father and mastermind, brought its trademark approach to a near-future techno-thriller called Strike Commander, which was released after considerable delay in the spring of 1993. It was only when gamers proved less receptive to the change in milieu than Roberts and Origin had hoped that the former turned his full attention at last to Wing Commander III: Heart of the Tiger.

At the time, the game that would eventually be released under that name was already in development, but the company’s ambitions for it were much smaller than they would soon become. The project was in the hands of what Robin Todd, a programmer on the project,[1]Robin Todd was living as Chris Todd at the time, and is credited under that name in the game’s manual. today calls a “small and inexperienced team”: “three main programmers with minimal game-dev experience, working cheap.” Their leader was one Frank Savage, an Origin-fan-turned-Origin-programmer so passionate about the Wing Commander franchise that his car bore the personalized license plate “WNGCMDR.” Had the group completed the game according to the original plan, it would likely have been released as yet another spinoff rather than the next numbered title in the series.

As it was, though, the project was about to take on a whole new dimension: Chris Roberts stepped in to become the “director” of what was now to be Wing Commander III. Having been recently acquired by Electronic Arts, Origin felt keenly the need to prove themselves to their new owners by delivering an unequivocal, out-of-the-ballpark home run, and the third major iteration of their biggest franchise seemed as close to a guaranteed commercial winner as one could hope to find in the fickle world of computer gaming.

Roberts had built his reputation on cutting-edge games that pushed the state of the art in personal-computer technology to its absolute limit; the first Wing Commander had been one of the first games to require an 80386 processor to run at all well, while Compaq had used Strike Commander as an advertisement for their latest Pentium-based computer models. Now, he decided that Wing Commander III ought to employ the latest technological development to take the industry by storm: not a new processor but rather the inclusion of live human actors on the monitor screen — as captured on videotape, digitized, overlaid onto conventional computer graphics, and delivered on the magical new storage medium of CD-ROM. From a contemporary interview with Roberts:

If you wanted to show your hot machine off back in 1990, Wing I was the game to do it. I think that right now we are in a phase where CD-ROM is becoming standard and everyone is getting a multimedia machine, but I don’t really think the software is out there yet that truly shows it off. That’s what I think Wing III is going to do.

Everyone’s been talking about interactive movies, but we hadn’t heard of anyone doing it right, so we wanted to go out and do it properly. With Wing III, we tried to apply the production values to an interactive movie that we’d applied on the computer side with the previous Wing Commanders. The goal was, if someone said, “What’s an interactive movie?” we’d just hand them the CDs from Wing Commander III and say, “Here, check this out.”

In keeping with his determination to make his interactive movie “right,” Roberts wanted to involve real film professionals in the production. Through the good offices of the California-based Electronic Arts, Hollywood screenwriters Frank DePalma and Terry Borst were hired; they were a well-established team who had demonstrated their ability to deliver competent work on time on several earlier projects, among them a low-budget feature film entitled Private War. Their assignment now was to turn Roberts’s plot outline into a proper screenplay, with the addition of occasional branch points where the player could make a choice to affect the flow of the narrative. After they did so, a Hollywood-based artist turned their script into a storyboard, the traditional next step in conventional film-making.

The thoroughgoing goal was to make Wing Commander III in just the same way that “real” movies were made. Thus a director of photography, assistant director, and art director as well were brought over from the film industry. And then came the hair and makeup people, the caterers, the Hollywood sound stage itself. Origin even spent some $15,000 trying to figure out how to digitize 35-millimeter film prints before being forced to acknowledge that humdrum videotape was vastly more practical.

The one great exception to the rule of film professionals doing what they did best was Chris Roberts himself, a 25-year-old programmer and game designer who knew precisely nothing about making movies, but who nevertheless sat in the time-honored canvas-backed director’s chair throughout the shoot with a huge how-did-I-get-here grin on his face. And why not? For a kid who had grown up on Star Wars, making his own science-fiction film was a dream come true.

That said, Wing Commander III was dramatically different from Star Wars when it came to the very important question of its budget: Origin anticipated that it would cost $2.8 million in all. This was an astronomical budget for a computer game at the time — the budgets of the most expensive, most high-profile games had begun to break the $1 million barrier only in the last year or two — but a bad joke by the standards of even the cheapest Hollywood production. Origin made up the difference by not building any sets whatsoever; their actors would perform on an empty sound stage in front of an expansive green screen, with all of the scenery to be inserted behind them after the fact by Origin’s computer artists.

Truly sought-after actors would cost far more than Origin had to spend, so they settled for a collection of hopeful up-and-comers mixed with older names whose careers were not exactly going gangbusters at the time, all spiced up with a certain amount of stunt casting designed to appeal to the typical computer-gaming demographic of slightly nerdy young men. At the head of the list, a real catch by this standard, was Mark Hamill — none other than Luke Skywalker himself. If some of his snobby Hollywood peers might have judged his appearance in a computer game as another sign of just how much his post-Star Wars career had failed to live up to popular expectations, Hamill himself, a good egg with both feet planted firmly on the ground, seemed to have long since made peace with that same failure and adopted a “just happy to have work” attitude toward his professional life. Wing Commander III wasn’t even his first computer game; he had previously voice-acted one of the roles in the adventure game Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers. He was originally recruited to Wing Commander III for the supporting role of Maniac, one of the player’s fellow pilots, who lives up to his name with a rather, shall we say, rambunctious flying style; only late in negotiations did he agree to take the role of Colonel Blair, the player-controlled protagonist of the story.

Joining him were other veteran actors who had lost some of their mojo in recent years, but who likewise preferred working to sitting at home: Malcolm McDowell, best known for his starring roles in the controversial A Clockwork Orange and the even more controversial Caligula during the 1970s; John Rhys-Davies, who had played Indiana Jones’s sidekick Sallah in Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (he would go on to enjoy something of a late-career renaissance when he was cast as Gimli the dwarf in the Lord of the Rings films); Jason Bernard, a perennial supporting actor on 1970s and 1980s television; Tom Wilson, who had played the cretinous bully Biff Tannen in the three Back to the Future movies. (He replaced Hamill in the role of Maniac — a role not that far removed from his most famous one, come to think of it.)

A more eyebrow-raising casting choice was Ginger Lynn Allen, a once and future porn star whose oeuvre may perhaps have been more familiar to more of Origin’s customers than might have admitted that fact to their mothers. (She played Blair’s sexy mechanic, delivering her innuendo with enthusiastic abandon: “Are we going to kick in the afterburners here?”; “There’s a lot more thrust in those jets than I imagined…”)

On the Set with Wing Commander III

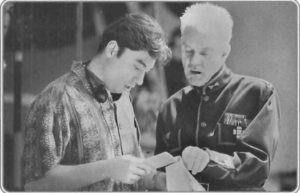

Jason Bernard, who played the captain of the Victory, the spaceborne aircraft carrier where Colonel Blair is stationed, is seen here with Mark Hamill, who played Blair himself.

Chris Roberts and Malcolm McDowell. The latter played Admiral Tolwyn, a human who is almost as much of an enemy of Colonel Blair as the Kilrathi.

Chris Roberts and John Rhys-Davies. The latter played Paladin, an old comrade-at-arms of Blair — he appears in the very first Wing Commander as a fellow pilot — whom age has now forced out of the cockpit.

Tom Wilson chats with a member of the film crew. He was by all accounts the life of the party on-set, and brought some of that same exuberance to Maniac, a rambunctious fighter jock. Computer Gaming World magazine gave him an award for “Best Male Onscreen Performance in Multimedia” for 1994 (a sign of the times if ever there was one). And indeed, a few more performances like his would have made for a more entertaining movie…

The actor inside a Kilrathi costume gets some much-needed fresh air, courtesy of a portable air-conditioning unit. Just about everyone present at the shoot — even those not ensconced in heavy costumes — has remarked on how hot it was on-set.

Shooting a scene with a Kilrathi. The costumes were provided by a Hollywood special-effects house. Their faces were animatronic creations, complex amalgamations of latex and machinery which could be programmed to run through a sequence of movements and expressions while the cameras rolled.

The 50-year-old John Rhys-Davies was the only cast member who showed any interest in actually playing Wing Commander III. Here he is at a press event, sitting next to the game’s media director Jenni Evans, whose herculean efforts helped to win the project an unprecedented amount of mainstream attention. Behind them stand Chris Roberts and Frank Savage; the latter managed development of the space simulator back in Austin while the former was off in Hollywood chasing his dream of directing his very own science-fiction film.

Computer Gaming World magazine would later reveal how much some of these folks were paid for their performances. As the star, Mark Hamill got $153,000 up-front and a guaranteed 1.75 percent of the game’s net earnings after the first 175,000 copies were sold; Jason Bernard got a lump sum of $60,000; Malcolm McDowell earned $50,000; Ginger Lynn Allen received just $10,000. (The same article reveals that Origin sought Charlton Heston for the game, but balked at his agent’s asking price of $100,000.)

Principal photography lasted most of the month of May 1994, although not all of the actors were present through the whole of filming. “More than 80 experienced film professionals worked up to eighteen-hour days in order to realize Chris Roberts’s vision of the final chapter of the Terran-Kilrathi struggle,” wrote Origin excitedly in their in-house newsletter to commemorate the shoot’s conclusion. “Although always intense and frequently frustrating, the shoot progressed without any major complications, thanks in part to a close monitoring of contracts, budgets, and schedules by resident ‘suits’ in both Austin and San Mateo.” (The latter city was the home of Electronic Arts.) Few to none of the actors and other Hollywood hands understood what the words “interactive movie” actually meant, but they all did their jobs like the professionals they were. In all, some 200 hours of footage was shot, to eventually be edited down to around three hours in the finished game.

The presence of so many recognizable actors on the set, combined with the broader mass-media excitement over multimedia and CD-ROM, brought a parade of mainstream press to the shoot. The Today show, VH-1, the Los Angeles Times, Premiere magazine, the Associated Press, USA Today, Newsweek, Forbes, and Fortune were just some of the media entities that stopped in to take some pictures, shoot some video, and conduct a few interviews. At a time when the likes of DOOM was still well off the mainstream radar, Wing Commander III was widely accepted as the prototype for gaming’s inevitable future. Even many of the industry’s insiders accepted this conventional wisdom about “Siliwood” — a union of Silicon Valley and Hollywood, as described by Alex Dunne that year in Game Developer magazine:

Ninety years after it first burst onto the scene, cinema is undergoing a renaissance. More than just a rebirth actually, it’s really a fusion with computer and video games that’s resulting in some cool entertainment: a new breed of interactive, “live-action” games featuring Hollywood movie stars. Such games, like Hell, Under a Killing Moon, and Wing Commander III, are coming out with more frequency, and they’re boosting the acting careers of some people in Tinseltown.

As Siliwood comes into its own, the line between games and movies will rapidly fade. Ads in game magazines already look like blockbuster movie ads, and we’ve begun to see stars’ mug shots alongside blurbs detailing the minimum system requirements. Interactive game drama is here, so forget the theater and renting movies — fire up the Intel nickelodeon.

Amidst all the hype, peculiarly little attention was paid to the other part of Wing Commander III, the ostensible heart of the experience: the actual missions you flew behind the controls of an outer-space fighter plane. This applied perhaps as much inside Origin as it did anywhere else. Chris Roberts was a talented game designer and programmer — he had, after all, been responsible for the original Wing Commander engine which had so wowed gamers back in 1990 — but his attention was now given over almost entirely to script consultations, film shoots, and virtual set design. Tellingly, Origin devoted far more resources to the technology needed to make the full-motion video go than they did to that behind the space simulator.

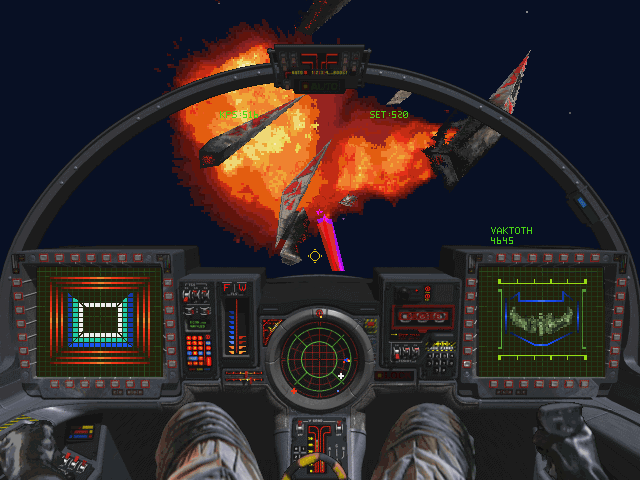

On the other hand, that choice may have been a perfectly reasonable one, given that they already had what they considered to be a perfectly reasonable 3D-simulation engine, a legacy of Strike Commander. Although that game had used VGA graphics only, at a resolution of 320 X 200, its engine had been designed from the start with the necessary hooks to enable Super VGA graphics, at a resolution of 640 X 480, when the time came. And that time was now. No one would be able to say that Wing Commander III‘s spaceflight sequences didn’t look very nice indeed. For its was a full-fledged 3D engine, complete with texture mapping and all the other bells and whistles. As such, it was a major upgrade over the one found in Wing Commander I and II, which had been forced by the hardware limitations of its time to substitute scaled sprites for real 3D models. With Roberts so busy scripting and filming his interactive movie, most of the responsibility for what happened in the cockpit continued to rest on the shoulders of Frank Savage, whose official title was now “game development director.”

Wing Commander III was a high-risk project for Origin. Since being acquired by Electronic Arts in September of 1992, they had yet to come up with a really big hit: Strike Commander had, as already noted, under-performed relative to expectations upon its release in the spring of 1993, while the launch of Ultima VIII a year later had been an unmitigated disaster. Under the assumption that you have to swing for the fences to hit a home run — or simply that you have to spend money to make money — Origin and their nervous corporate parent didn’t object even when Wing Commander III‘s budget crept up to $4 million, making it the most expensive computer game ever made by a factor of more than two. Their one inflexible requirement was that the game had to ship in time for the Christmas of 1994. And this it did, thanks to the absurdly long hours put in by everyone; not for nothing would Origin go down in history as the company that largely invented crunch time as the industry knows it today. Programmer Robin Todd:

In retrospect the crunch was vicious, but at the time I had nothing else to compare it to. Everything was a blur during the months before we shipped. At whatever time I was too tired to go on programming, I’d go back to my apartment to sleep. And when I woke up, I’d go back to the office. And that was it. What time of day it was didn’t matter. I remember the apartment manager knocking on my door one morning because I was so spaced from working that I’d forgotten to pay my rent for weeks. Sleeping under our desks started as something of a joke, but it quickly became true. There was one designer who wanted to take the evening off for his mom’s birthday, and was told that if he did, then he shouldn’t bother coming back.

I shared an office with two designers, and during a particularly late evening, one of the them turned to me and said, “If I’m still here when the sun comes up, I quit.” And sure enough, we were still there at dawn. He got up and turned in his resignation.

The day the project went gold I tendered my resignation.

At the last minute, it was discovered that the four CDs which were required to contain the game were packed a little too full; some CD-ROM drives were refusing to read them. A hasty round of cuts resulted in a serious plot hole. But so be it; the show went on.

This wall inside Origin’s offices tracked Wing Commander III‘s progress from genesis to completion for the benefit of employees and visitors alike.

Publicly at least, Chris Roberts himself expressed no concern whatsoever about the game’s commercial prospects. “I have a name brand,” he said, adopting something of the tone of the Hollywood executives with whom he’d recently been spending so much time. “I am not going to lose money on it.” He predicted that Wing Commander III would sell 500,000 copies easily at a suggested list price of $70, enough to bank a tidy profit for everyone — this despite the fact that it required a pricey Pentium-based computer with a fast SVGA graphics card to run optimally, a double-speed CD-ROM drive to run at all.

His confidence was not misplaced. Three major American gaming magazines put Wing Commander III on their covers to commemorate its release in November of 1994, even as features appeared across mainstream media as well to greet the event. Ginger Lynn Allen appeared on Howard Stern’s nationally syndicated radio show, while Malcolm McDowell turned up on MTV’s The Jon Stewart Show. Segments appeared on Entertainment Tonight and CNN; even Japan’s Fuji TV aired a feature story. In short, Wing Commander III married its title of most expensive game ever to that of the most widely covered, most widely hyped computer-game debut in the history of the industry. Within ten months of its release, Next Generation magazine could report that its sales had surpassed Roberts’s predicted half a million copies. Once ported to the Apple Macintosh computer and the 3DO and Sony PlayStation consoles, its total sales likely approached 1 million copies.

It doubtless would have sold even better in its original MS-DOS incarnation if not for those high system requirements and its high price. As it was, though, Origin and Electronic Arts were satisfied. The Hollywood experiment had proved a roaring success; Wing Commander IV was quickly green-lit.

One of my briefs in articles like this one is to place the game in question into its historical context; another is to examine it outside of that context, to ask how it holds up today, what other designers might learn from it, and whether some of you readers might find it worth playing. This is the point in the article where I would normally transition from the one brief to the other. In this case, though, it strikes me as unfair to do so without at least a little bit of preamble.

For, if it’s self-evident that all games are products of their time, it’s also true that some seem more like products of their time than others — and Wing Commander III most definitely belongs in this group. There is a very short window of years, stretching from about 1993 to 1996, from which this game could possibly have sprung; I mean that not so much in terms of technology as in terms of concept. This was the instant when the “Siliwood” approach, as articulated by Alex Dunne above, was considered the necessary, well-nigh inevitable future of gaming writ large. But of course that particular version of the future did not come to pass, and this has left Wing Commander III in an awkward position indeed.

Seen from the perspective of today, a project like this one seems almost surreal. At what other moment in history could a complete neophyte like Chris Roberts have found himself behind the camera directing veteran Hollywood talent who had previously worked under the likes of George Lucas and Stanley Kubrick? It was truly a strange time.

The foregoing is meant to soften the blow of what I have to say next. Because, if you ask me whether Wing Commander III is a good game in the abstract, my answer has to be no, it really is not. It’s best reserved today for those who come to it for nostalgia’s sake, or who are motivated by a deep — not to say morbid! — curiosity about the era which it so thoroughly embodies.

I can hardly emphasize enough the extent to which gaming during the 1990s was a technological arms race. Developers and publishers rushed to take advantage of all the latest affordances of personal computers that were improving with bewildering speed; every year brought faster processors and CD-ROM drives, bigger memories and hard drives, graphics and sound cards of yet higher fidelity. The games that exploited these things to raise the audiovisual bar that much higher dazzled the impressionable young journalists who were assigned to review them so utterly that these earnest scribes often described and evaluated their actual gameplay as little more than an afterthought. Computer Gaming World was the most mature and thoughtful of the major American magazines, and thus less prone to this syndrome than most of its peers. By no means, however, was it entirely immune to it, as Martin E. Cirulis’s five-stars-out-of-five review of Wing Commander III illustrates.

They say that every successful person carries within her the seeds of her own destruction. In the same spirit, many a positive review contains the makings of a negative one. After expounding at length on how “simply incredible” the game is, Cirulis has this to say:

I’m afraid I’ve come to the conclusion that the space-combat aspect of Wing Commander III is almost incidental to playing the thing. The story you are moving through is so interesting and the characters so well-detailed that you almost wish you didn’t have to strap into the fighter just to see what happens next. The story line of a Wing Commander game used to be a gimmick to make what was basically a space-combat game seem more interesting, especially to people who weren’t dedicated sim pilots; but things have come full circle now, and it’s the story that is the point and the flight sim that is the gimmick.

I realize that there will be those who think that I have been blinded by chrome and taken in by pretty pictures and have failed to “critique the game.” Well, more power to them.

Another writer — perhaps even one named Martin E. Cirulis at another moment in time — might frame a review of a game whose cut scenes are its most entertaining part rather differently. Sadly, I’m afraid that I have to become that writer now.

By the standards of most productions of this nature, the game’s cinematic sequences don’t acquit themselves too horribly. If you can look past the inherent cheesiness of pixelated human actors overlaid upon computer-generated backgrounds, you can see some competent directing and acting going on. The game’s eleven-minute opening sequence in particular shows a familiarity with the language of cinema that eludes most other interactive movies. Throughout the game, there is a notable lack of the endless pregnant pauses, the painful periods where the director seems to have no idea where to point the camera, the aura of intense discomfort and vague embarrassment radiating from the actors that was such par for the course during the full-motion-video era. Likewise, the script shows an awareness of how to set up dialog and use it to convey information clearly and concisely.

I give the film-making professionals who helped Chris Roberts to “direct” his first feature film more credit for all of this than I do that young man himself. (Anyone who has seen the later, non-interactive Wing Commander movie knows that Roberts is no natural-born cinematic auteur.) Rather credit him and the rest of Origin for realizing that they needed help and going out and getting it. This unusual degree of self-awareness alone placed them well ahead of most of their peers.

At the same time, though, the production’s competence never translates into goodness. There’s a sort of fecklessness that clings to the thing, of professionals doing a professional job out of professional pride, but never really putting their hearts into it. It’s hard to blame them; the plot outline provided by Roberts was formulaic, derivative stuff, right down to climaxing with a breakneck flight down a long trench. (Star Wars much, Mr. Roberts?) And the less said the better about the inevitable love triangle, in which you must choose between a good girl and a bad girl who both have the hots for you; it’s just awful, on multiple levels.

In cinematic terms, the whole thing is hopelessly stretched in length to boot, a result of the need to give customers their $70 worth. One extended blind alley, involving a secret weapon that’s supposed to end the war with the Kilrathi at a stroke, ends up consuming more than a quarter of the script before it’s on to the next secret weapon and the next last remaining hope for humanity… no, for real this time. The screenwriters noted that their movie wound up having seventeen or eighteen acts instead of the typical three. Putting the best spin they could on things, they said said that scripting Wing Commander III was like scripting “a little miniseries.”

The acting as well is a study in competence without much heart. The actors do their jobs, but never appear to invest much of themselves into their roles; Mark Hamill seems to have had much more fun playing the slovenly Detective Moseley in Gabriel Knight that he did playing the straight-laced Colonel Blair here. Again, though, the script gives the actors so little to work with that it’s hard to blame them. The parade of walking, talking war-movie clichés which they’re forced to play are all surface on the page, so that’s how the actors portray them on the screen. Only Tom Wilson and Ginger Lynn Allen bring any real gusto to their roles. Tellingly, they do so by not taking things very seriously, chewing the (virtual) scenery with a B-movie relish. I don’t know whether more of that sort of thing from the others would have made Wing Commander III a better film under the criteria Chris Roberts was aiming for, but it certainly would have made it a more knowing, entertaining one in my eyes.

Instead, and as usual for a Chris Roberts production, the painful earnestness of the whole affair just drags it down. For all its indebtedness to Star Wars, Wing Commander III lacks those movies’ sense of extravagant fun. Roberts wants us to take all of this seriously, but that’s just impossible to do. The villains are giant cats, for heaven’s sake, who look even more ridiculous here than they do in the earlier games, like some overgrown conglomeration of Tigger from Winnie the Pooh and the anthropomorphic chimpanzees from Planet of the Apes.

As is the norm in games of this style, your degree of actual plot agency in all of this is considerably less than advertised. Yes, you can pick the good girl or the bad girl, or reject them both; you can pick your wingman for each mission; you can choose your character’s attitude in dialog, which sometimes has some effect on others’ attitudes toward you later on. But your agency is sharply circumscribed by the inherent limitations of pre-shot, static snippets of video and the amount of storage space said video requires; it was enough of a challenge for Origin to pack one movie onto four CDs, thank you very much. These limitations mean you can’t steer the story in genuinely new directions during the movie segments. The “interactive” script is, in other words, a string of pearls rather than a branching tree; when you make a choice, the developers’ priority is to acknowledge it more or less perfunctorily and then to get you back into the main flow of their pre-ordained plot.

The developers did design a branching mission tree into the game, but your progression down it is dictated by your performance in the cockpit rather than by any conscious choices you make outside your spacecraft. Nevertheless, there are some generous touches here, including a heroic but doomed last stand of a mission if the war goes really badly. But Origin knew well by this point that most players preferred to replay failed missions instead of taking their lumps and continuing down the story’s “losing” branch, and this knowledge understandably influenced the amount of work they were willing to put into crafting missions which most players would never see; the alleged mission tree in this game is really a linear stream with just a few branching tributaries which either end or rejoin the main flow as quickly as possible. Certainly the most obvious problem with the approach — the fact that the branching mission tree gives less skilled players harder missions so that they can fail even worse after failing the first time, while it gives more skilled players easier missions that might well bore them — is not solved by Wing Commander III.

When it comes to its nuts and bolts as a space simulator, Wing Commander III surprises mostly by how little it’s progressed in comparison to the first two games. The 3D engine looks much better than what came before, is smoother and more consistent, and boasts the welcome addition of user-selectable difficulty levels. At bottom, though, the experience in space remains the same; neither the ships you fly nor their weapons load-outs have changed all that much. The engine’s one genuinely new trick is an ability to simulate flight over a terrestrial landscape, a legacy of its origins with the twentieth-century techno-thriller Strike Commander. Yet even this new capability isn’t utilized until quite late in the game.

Wing Commander III runs at a much higher resolution than the first Wing Commander, but the general look of the game is surprisingly little changed, as this direct comparison shows. This is not necessarily a bad thing in itself, of course — there’s something to be said for a franchise holding onto its look and feel, as Origin learned all too well when they attempted to foist the misbegotten Ultima VIII upon the world — but the lack of any real gameplay evolution within that look and feel perhaps is.

Each of the 50 or so missions which you have to fly before you get to that bravura climax breaks down into one of just a few types — patrol these waypoints, destroy that target, or protect this vessel — that play out in very similar ways each time. There’s never much sense of a larger unfolding battle, just a shooting gallery of Kilrathi coming at you. The artificial triggers of the mission designs are seldom well-concealed: reaching this waypoint magically spawns a Kilrathi fighter squadron from out of nowhere, reaching that one spawns a corvette. Meanwhile the need to turn on the auto-pilot and slew your way between the widely separated waypoints within most missions does little for your sense of immersion. Wing Commander III isn’t a complete failure as an arcadey space shooter; some players might even prefer its gung-ho, run-and-gun personality to more nuanced approaches. But I would venture to say that even some of them might find that it gets a little samey well before the 50 missions are complete. (Personally, I maintain that the first Wing Commander, which didn’t stretch itself so thin over so many missions and which was developed first and foremost as a compelling action game rather than an interactive movie, remains the best of the series from the standpoint of excitement in the cockpit.)

Looking back on 1994 from the rarefied heights of 2021, I find that Wing Commander III‘s weaknesses as both interactive movie and space simulator are highlighted by the strengths of a contemporary competitor in both categories.

In the former category, we have Access Software’s Under a Killing Moon, which was released almost simultaneously with Wing Commander III; the two games were often mentioned in the same breath by the trade press because each packed four CDs to the bursting point, giving each an equal claim to the title of largest game ever in terms of sheer number of bytes. Under a Killing Moon was a more typical early full-motion-video production than Wing Commander III in many ways, being a home-grown project that utilized the talents of only a few hired guns from Hollywood. But, for all that the actors’ performances and the camera work often betray this, the whole combines infectious enthusiasm — “We’re making a movie, people!” — with that edge of irony and humor that Chris Roberts’s work always seems to lack. If Wing Commander III is the glossy mainstream take on interactive cinema, Under a Killing Moon is the upstart indie version. It remains as endearing as ever today, one of the relatively few games of its ilk that I can unreservedly recommend. But then, I do tend to prefer the ditch to the middle of the road…

In the realm of space simulators, we have LucasArts’s Star Wars: TIE Fighter, which shipped about six months before Wing Commander III. Ironically given its own cinematic pedigree, TIE Fighter had no interest in Hollywood actors, love triangles, or even branching mission trees, but was rather content merely to be the best pure space simulator to date. Here you can’t hope to succeed as the lone hero charging in with guns blazing; instead you have to coordinate with your comrades-in-arms to carry out missions whose goals are far more complex than hitting a set sequence of waypoints, missions where dozens of ships might be pursuing individual agendas at any given time in dynamic unfolding battles of awesome scale. It’s true that TIE Fighter and its slightly less impressive predecessor X-Wing would probably never have come to exist without the example of the Wing Commander franchise — but it’s also true that LucasArts had well and truly bettered their mentors by the time of TIE Fighter, just their second attempt at the genre.

And now, reading back over what I’ve written, I see that I’ve been as unkind to Wing Commander III as I’d feared I would. Therefore let me say clearly now that neither half of the game is irredeemably bad; I’ve enjoyed action and simulation games with much more hackneyed storytelling, just as I’ve enjoyed narrative-oriented games whose writing and aesthetics are more interesting than their mechanics. The problem with Wing Commander III is that neither side of it is strong enough to make up for the failings of the other. Seen in the cold, hard light of 2021, it’s a poorly written low-budget movie without any vim and vinegar, married to an unambitious retread of a space shooter.

But in the context of 1994, of course, it was a very different story. The nerdy kitsch that most of us see when we look at the game today in no way invalidates the contemporary experiences of those who, like Computer Gaming World‘s Martin E. Cirulis, looked at it and decided that “we are witnessing the birth of something new.” The mid-1990s were a period of tremendous ferment in the world of computing, with new possibilities seeming to open up by the month. Wing Commander III is, whatever else it may be, a reflection of that optimistic time, as it is of the spirit of its wide-eyed creator and its hundreds of thousands of players who were not all that different from him, who came to it ready and willing to be wowed by it. Its unprecedented budget alone made a powerful statement, being tangible proof that computer gaming was becoming a big business that everyone in media had to take seriously.

Created in the best of faith and with the noblest of intentions to move gaming forward, Wing Commander III seemed like a dispatch from the future for a brief window of time. In the long run, though, the possible future it came from was not the one that its medium would wind up embracing, leaving it stranded today on an island of its own making. Such is sometimes the fate of pioneers.

Some Scenes from the Film

(Sources: The books Origin’s Official Guide to Wing Commander III and Wing Commander III: Authorized Combat Guide; Computer Gaming World of September 1994, December 1994, and February 1995; Game Developer of February/March 1005 and June/July 1995; CD-ROM Today of August/September 1994; Next Generation of November 1995; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of May 6 1994, June 3 1994, July 15 1994, September 9 1994, October 7 1994, November 23 1994, January 13 1995, February 10 1995, March 14 1995, April 7 1995, and May 3 1995. Online sources include the Wing Commander Combat Information Center‘s treasure trove of information on the game. And thank you to Robin Todd for sharing with me her memories of working on Wing Commander III, crunch time included.

Wing Commander III is available today as a digital purchase at GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Robin Todd was living as Chris Todd at the time, and is credited under that name in the game’s manual. |

|---|

Sean Barrett

March 5, 2021 at 6:14 pm

I remember one striking technical innovation in WC3–while the cutscenes played out in a standard for-the-time resolution (320×200-ish), the scenes moving around the ship were in a much higher resolution like 640×480, and seeing the characters (static, or maybe they had two frames?) at that resolution was a novelty and quite compelling. (Under a Killing Moon also used a resolution like 640×480 for its gameplay segments and I assume a lower resolution for its movies). Of course this seems laughable now, but after only seeing cutscenes at 320×200 (or lower!) at the time, this was pretty significant.

On the other hand, I remember spending like an hour in that final trench run, and I never figured out why. I guess the targeting indicator broke or something, so instead of leading me to the target it just kept leading me in circles (why was the trench a circle?). Eventually I gave up and flew over the mountains and finished the game (or lost the game, I honestly don’t remember now).

Jimmy Maher

March 5, 2021 at 9:01 pm

I believe the movies ran at 640 X 480, while the flight simulator could run in either VGA or SVGA resolutions, depending on how much computing horsepower you had to hand. Regardless, the sort of intra-game resolution hopping you describe wasn’t at all uncommon during the industry’s period of transition between VGA and SVGA. The CD-ROM editions of X-Wing and TIE Fighter had cut scenes and menu screens in VGA, while the flight sequences themselves could optionally run in SVGA. Even the Legend adventure game Death Gate had pre-rendered 3D movies running at 320 X 200, while the main game ran in SVGA.

Josh Martin

March 6, 2021 at 11:12 pm

The movies in WC3 are actually a meager 320×165, displayed at 320×200 via the addition of black bars on the top and bottom. The frame rate is also limited to 15fps. You can check out some raw video from the game (as well as WC4 and Crusader: No Regret) here; they play fine under VLC, though you may have to let it to a quick repair process first.

Higher-res video with smoother frame rates wasn’t really an option at the time, due to both the capacity of CD-ROMs and the fact that CPUs at the the time didn’t have the horsepower to decode it. MPEG cards (first for MPEG-1, then later for MPEG-2) were supposed to help with that, but they never got widespread adoption or publisher support—the makers of the ReelMagic card (the most prominent such example) promised a whopping 61 titles would eventually ship with ReelMagic support, but so far nobody’s been able to prove the existence of more than ten.

The original DOS CD-ROM version of Wing Commander IV used a slightly improved video codec that still operated at 320×165 at 15fps, but with added “scanlines” (meaning a black line inserted every other line) to create the illusion of a higher resolution. A patch for Windows 95 machines allowed you to remove the scanlines, but this just duplicated every line and didn’t give you true high-res video. The subsequent DVD-ROM version had MPEG-2 video at 640×480 and (mostly) 30fps, but at the time you needed a decoder card to play it. Early DVD-ROM drives were usually bundled with these so that wasn’t an issue at the time, but eventually CPUs became fast enough to handle MPEG-2 without a dedicated card and some enterprising community members went in and hacked the game to allow this. I believe this is the version you can buy on GOG now.

Josh Martin

March 6, 2021 at 11:12 pm

Apologies for the broken italics tag.

Jimmy Maher

March 7, 2021 at 8:55 am

I stand corrected. (I seem to have been doing a lot of that lately…) Thanks!

Tom

March 5, 2021 at 9:40 pm

Yeah, I had the same issue with the trench run the first time I tried it; kept going and going, but never resolved.

I must have restarted the mission at some point and finished it, as I did win the game eventually.

lee

March 5, 2021 at 7:02 pm

> Because, if you ask me whether Wing Commander III is a good game in the abstract, my answer has to be no, it really is not.

I started to get all huffy and angry and I came down here to comment, but after starting and then deleting like four different posts…I have to agree.

What tips the scales for me is how I actually reacted to the game when it came out. WC3 was the first CD-ROM game I ever bought, the day after Christmas 1994, and while I absolutely insufflated it once I got it home and installed, my memories of the game mostly involve being in love with the idea of having a movie playing on my computer screen.

Sure, there were some amazing moments—Jason Bernard’s reaction to Blair ejecting during a mission is possibly one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen (“You know those ships are expensive, right? You think I got elves in the back making more of them??!”)—but all of those amazing moments were on the FMV side, not the gameplay side. The actual gameplay was a chore—it was the thing I had to get through in order to get back to the part of the game I was really there for.

It’s hard facing the fact that a game I remember so fondly was just objectively a crappy game, but here we are.

Matthew

October 5, 2021 at 3:25 am

I remember one choice getting a pilot killed. Bernard’s character reacted with such fury that I didn’t want to make any mistakes in the game again. A really underrated actor.

My problem with WC3 is really my problem with the whole series. The first game trafficked in a lot of cliches, but for 1990 it was a revolutionary approach to video storytelling and I got engaged with the characters and this ship they were on. (The manual helped a lot there.) Col. Halcyon says goodbye to all the pilots at the end of one mission, and lord, I felt like that character was alive.

Aaaaand they destroyed the ship and killed almost all the characters I loved at the start of WC2.

But OK! WC2 had a more creative, inventive plot, with real stakes attached. The survivors of the Tiger’s Claw seemed scarred by war and there was a lot of believable bickering. The Special Operations packs were fine, except at the end of each one they rewarded all your hard work by saying “ha ha, the Kilrathi are actually stronger now” but hey — a good basis for a sequel, right?

Aaaaaand they killed almost everyone at the start of WC3. I hated the game for that, and the stupid plot twist with Hobbes that made his noble self-sacrifice in the second game meaningless.

Peter Olausson

March 5, 2021 at 8:04 pm

Just realised there was only seven years between John Rhys-Davies in Wing Commander III and Lord of the Rings, which was released 20 years ago. Time sure isn’t what it used to be.

Lt. Nitpicker

March 5, 2021 at 8:07 pm

There are some erroneous statements of the game costing 90 dollars, and a claim of Intel showing off Strike Commander as an example of the Pentium’s power when the earlier “Origin Sells Out” article claims its Compaq.

ChrisReid

March 6, 2021 at 12:14 am

The base game MSRP was $69.95, but they did also sell a premiere edition for $99.95: https://cdn.wcnews.com/newestshots/full/origin_holiday_cd_mailer_side_1.jpg

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2021 at 7:58 am

The Computer Gaming World review gives the price as $80 (or rather $79.95). It looks like there must have been a last-minute price adjustment after the magazine went to print. Thanks!

Firehawke

March 5, 2021 at 8:36 pm

I think the question that I come out of this with is…

“If there were 200 hours of footage originally, what happened to that footage?”

I wonder if Chris Roberts might still have some of that. It’d be really interesting to see that material get put up on Internet Archive for preservation, and I think that footage might explain some of the weird plot hole problems WC3 had.

As for gameplay, I felt WC3 wasn’t worse than WC2– it was certainly more of the same, but I felt (at the time, and equally still today) that more of the same was fine. It’s not like they really could do that much more for the genre outside of maybe fixing the branching missions concept. That is, of course, something you comment on.

I’d be interested in hearing how you’d compare 4 and Prophecy with 3.

Jimmy Maher

March 5, 2021 at 9:14 pm

I don’t know whether the footage was preserved, but regardless, it’s probably far less exciting than you might be imagining. At a Hollywood-style shoot like this one, multiple cameras are rolling to capture the action from different angles, and are generally doing so more or less constantly: “Action!” and “Cut!” are more signals to the actors than to the camera operators in the film productions of recent decades. So, what you’ll have is hours and hours of people milling around on-set, mixed with multiple takes of the same scenes from multiple angles. The best you might hope to put together is a few choice blooper reels, many of them perhaps involving Tom Wilson, the life of the party on-set.

Gordon Cameron

March 6, 2021 at 5:32 am

I don’t think even with video you’d typically film people milling around on set, unless you’re specifically making a behind-the-scenes documentary.

I’ve only worked on lower budget productions, but as recently as 2008 the standard slating technique, plus “Roll sound – speed – action – cut!” were the norm. Cameras were not rolling most of the time; they’d just catch grips fiddling with lights and C-stands and such. Obviously since video is less expensive to roll than film, there’s a tendency to be a bit more casual about it – the Coen brothers noted that when shooting on digital, actors want to try multiple line readings in a single take, for example – but the idea of making each shot a discrete, labeled entity has purposes other than saving money. It also is important for logging and categorizing all the footage so that the editors can make sense of it later.

As to using multiple cameras to film actual onscreen action that’s supposed to be in the movie – well, I think that depends on the director. Kurosawa is supposed to have made use of multiple cameras in some of his films, although I’m not sure whether he reserved that for big stunts and action scenes rather than for simple dialogue setups. Sitcoms of course usually would go multi-camera but that’s because they were performed live. When you have an expensive stunt or explosion or effects shot that you can only do once or that costs a ton of money each time you do it, you will of course want lots of cameras rolling on it.

In my background in film school and in the productions I was on, it was not the norm to shoot multiple angles simultaneously for typical dialogue scenes. Shooting a master and then subsequently shooting the rest of the coverage (closeups, inserts, etc.) was the normal approach we were taught. Often actors reserve their best stuff for when they know it’s their closeup, obviously, though I suppose they’d have to alter that if they knew all angles were being shot at the same time.

I imagine that some high-level directors like to use multiple cameras more frequently and some don’t, and the technique might have become more common in the age of digital shooting; but you have to factor in that it’s harder for the cinematographer to control the lighting when worrying about multiple angles simultaneously, and also the more angles you have, the more you have to worry about keeping production gear/lights/etc. out of the shot. A director might also prefer in dramatic scenes to be able to focus on one performance at a time during closeups, reserving the master shot for just setting up the initial geography of the scene and providing a safety net if the editor can’t otherwise cut out of the closer shots.

If I had to guess I’d imagine some of the WC3 extra footage would have been deleted scenes, and a lot would just have been takes they didn’t use, or coverage they shot to be safe that didn’t end up being needed in the editing room. Apparently a 10-1 ratio of shot-to-used footage was pretty common in Golden Age Hollywood. (See here: https://nofilmschool.com/2016/03/shooting-ratios-mad-max-fury-road-primer-hitchcock) The ratio on Wing Commander III sounds like it was closer to 60-1, which is indeed pretty extreme. Maybe it was a function of Roberts’s inexperience/lack of confidence as a filmmaker and a desire to make sure all the bases were covered, and/or a lot of little story branches they shot but then didn’t implement?

Either way I doubt there was much footage of people milling around on set. At any rate, when I edited a low budget feature shot on digital in ’08, I’d have been tearing my hair out if I’d had to sift through all that instead of properly slated and labeled takes.

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2021 at 8:04 am

I was describing my understanding of these things from some casual conversations I’ve had with people involved in professional film production. But obviously I misunderstood them to some extent; you clearly know far more about these things than I do. Thanks so much for your detailed explanation. The only additional wrinkle might be the need to superimpose computer graphics on the scenes during post-production. I don’t know whether this would make running multiple cameras more desirable — i.e., so that everyone is always standing in the same place.

The claimed 200 hours of footage showed up in Origin’s internal newsletter. It’s possible that the writer was simply mistaken, or even inserted a zero too many. I agree that it does seem extreme. Shooting that much in a month would require shooting about six and a half hours per day if you never took a day off. You would almost have to have just let the cameras roll.

Michael

March 8, 2021 at 11:28 pm

Indeed, “the need to superimpose computer graphics on the scenes during post-production” can be taken as reasonable proof that there were not multiple cameras rolling. The green screen would need to be behind the actors, not off to one side, for this to work. Hence, you could only shoot from one angle at a time.

F

March 5, 2021 at 9:15 pm

The original Wing Commander wasn’t so terrible on my 16mhz 286 at the time. Slow, but doable. In a strange twist that would become commonplace only much later, extra expanded memory (requiring a 386 with the EMM386 extension) would allow for improved graphical effects such as seeing your own hand and yoke in the cockpit and fancier explosions. Oh, the memories …

Also, “voiced-acted”.

Jimmy Maher

March 5, 2021 at 9:17 pm

Thanks!

Tom

March 5, 2021 at 9:46 pm

A fair assessment. WC3 was certainly a product of it’s time. And at the time, it was pretty heady stuff. Maybe not for the game itself, but the promise of what might be done with that technology in the future.

One thing that made an impact on me was the sheer size of the Behemoth, taking minutes to fly all the way around it (and even inside it). It provided a sense of scope for an in-game object that I had never experienced before – even the star destroyers in X-Wing/TIE Fighter seemed somehow small and constrained in comparison.

Kevin Christman

March 6, 2021 at 12:24 am

So, I’ve barely played the DOS version, but I’ve played a ton of the 3DO version and it’s probably my favorite space sim next to TIE Fighter. I’ve never seen anyone document the changes, but they changed quite a bit- mostly simplifications, especially combat with capital ships. This kind of thing could of course go either way depending on your tastes/expectations, but in practice I feel like it’s just more fun.

One big obvious drawback is the lack of buttons, meaning you have to memorize certain button combos. Once you scale that wall- and realistically you only need to regularly use a couple of them so this isn’t as daunting as it sounds- it’s a plenty good time.

Bobby

March 6, 2021 at 2:51 am

Given how hyped this was, I think a lot of people bought it who hadn’t played the previous entries. That’s why it could get away with gameplay that didn’t improve on them

John

March 6, 2021 at 3:18 am

I never played Wing Commander III–I was more of a Privateer man–but a friend of mine was a real evangelist for the game. Once, when we were gathered at another friend’s house to watch a movie on their big screen TV, he forced us to watch a VHS tape with a bunch of captured Wing Commander III cutscenes first. I wish I could have shared his enthusiasm for the game. It’s true that the cutscenes were impressive . . . for a computer game of the time. Unfortunately for my enthusiastic friend, however, the movie we were there to watch was Star Wars, which of course made Wing Commander III look amateurish by comparison. I sometimes wonder if the cutscenes would have impressed me more if I’d seen them in their proper context on a computer screen and perhaps had the chance to play a bit of the game along with them.

Gordon Cameron

March 6, 2021 at 5:35 am

The quote snippet about crunch at Origin was tough to read. I never realized that the situation was that bad, and it takes some of the bloom off my glowy nostalgic feeling about early-90s Origin.

Aula

March 6, 2021 at 3:09 pm

“you must chose between”

choose

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2021 at 6:20 pm

Thanks!

Juan G

March 6, 2021 at 3:58 pm

Somehow, I never got to actually play much of Wing Commander III for myself, despite being anxious to do so because of my love for the second entry in the series, but it’s still very interesting to learn about its production history from a modern perspective.

That said, I distinctly remember finding its sequel Wing Commander IV to work quite well as a movie, presumably because they had higher ambitions in mind thanks to creating at least two significantly different branching story paths (which involved the threat of civil war between human enemies, while the space cats are no longer a concern) and they almost certainly spent more money on the cinematic side after the success of III.

Can’t say I had any real issues with the actual gaming aspect of it either. I’d want to argue IV played about as well as you’d expect from a Wing Commander title, but that may just be me. Again, I’d assume they tweaked the engine after III and ironed out any remaining oddities.

At the same time, I think it’s inevitably bittersweet to read about even the more or less controversial entries from the classic WC series, in retrospect, considering what Christ Roberts has been attempting with Star Citizen and the whole bloody mess behind that particular ongoing project’s endless milking (or perhaps calling it a gig would be more appropriate).

Juan G

March 6, 2021 at 4:01 pm

It should be Chris, not Christ, but then again that particular mistake seems oddly fitting too.

Nils

March 6, 2021 at 10:44 pm

I remember WC4 being touted as the most expensive game ever produced around the time of its release, so I’m sure they did use more money. They used actual sets that time, after all.

IV plays quite similar to III, but the enemies are more dangerous (missiles this time!) and the missions tend to be shorter and a bit more varied, with at least some kind of twist to the ”search every waypoint, shoot everyone” formula. I guess it’s an improvement, but Wing Commander just isn’t Wing Commander without the Kilrathi…

Jimmy Maher

March 7, 2021 at 8:58 am

Yes, Wing Commander IV got a banner cover in Computer Gaming World as the first $10 million computer game — a demonstration of how quickly budgets were escalating, given that it appeared just two years after the $4 million Wing Commander III became the most expensive computer game ever.

Josh Martin

March 7, 2021 at 8:01 pm

WC4 was also shot on 35mm instead of videotape, which wasn’t a super obvious improvement with the original CD version but was much more evident on the DVD-ROM release with higher-resolution video. (It also means they could create a full HD remake by going back and rescanning the footage, but there’s a less than zero chance that modern EA will bother with that.) As for the actual gameplay, it addressed one of Jimmy’s complaints about part 3 by adding more ground-based missions, but the game uses a one-size-fits-all flight model for both space and planetside areas, so they don’t feel that much from different from space missions with really really really big capital ships.

Sebastian Gerstl

March 6, 2021 at 4:41 pm

I have a small correction to make:

“In some ways, the series has even regressed; you can no longer jump behind the controls of a rear-facing laser turret, as you could in Wing Commander II.”

That’s not true, you can in both the Thunderbolt-Fighter and the Longbow-Bomber. You don’t have side-facing turrets like in the Broadsword in WC2 any more – but to be fair, hardly anyone ever used those. :P

I was a huge Wing Commander fan growing up and have played the games endlessly over the years (maybe even too much :p ) and I will always defend the shooting mechanics over the X-Wing/Tie Fighter games. Even though WC3 deliberately lifted a few mechanics from those, like redistributing the energy to guns, shields and damage repair, the ability to use pseudo-Newton mechanics (called ‘Shelton gliding’ in-game) for two spaceship models…

So no, while I think the article was well-written and hits the nail on the head on many occasions, I don’t agree with the assessment that the mechanics allegedly regressed in any form or fashion. ;)

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2021 at 6:21 pm

I inserted that sentence during my final editing pass, always a dangerous thing to do. ;) Thanks!

Nils

March 6, 2021 at 7:38 pm

There’s also at least one more planetary mission before the showdown at Kilrah, though it too is quite far into the game.

Compared to WC2, I think that the missions in WC3 are a bit of a step back. WC2 uses a lot of in-mission cutscenes, but WC3 has like one? WC2 missions also don’t drag on and on like many later ones in WC3 do, with multiple waves of enemies at every checkpoint who all must be taken down.

It’s too bad that unlike its predecessors, the WC3 engine would allow mixing enemy types, but this rarely happens. On the default difficulty or the onr above it, the Kilrathi never use missiles either, which almost feels like a bug.

What’s that plot hole introduced by the cuts?

BTW, lately my Android Chrome refuses to show the smartphone version of the site, making it hard to read. Is it me, or has sonething broken in the last few weeks or so?

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2021 at 8:48 pm

Fair enough. Thanks! The mobile issue should be fixed now.

Sebastian Gerstl

March 6, 2021 at 9:46 pm

I am also curious what plot hole you’re referring to – it’s been a while since I last played the game, but nothing obvious would spring to mind right now…

Alex Smith

March 6, 2021 at 10:05 pm

Assuming Jimmy and I are thinking of the same thing, it’s not so much a plot hole as a point of extra clarification. Spoilers ahead for a nearly 30 year old game.

After Hobbes turns trailer, he leaves a holo message in Blair’s locker explaining that he was a deep cover agent created using a personality matrix something or another that made him a completely different person essentially. He was activated by his handlers and did his thing. This holo was cut, so the betrayal is just super random and never explained.

Sebastian Gerstl

March 7, 2021 at 6:12 am

That’s weird… I have the German version of the game, as it was released in 1994, and the holo is there… It was missable, since it was an optional scene that had to be accessed by clicking on your locker after a certain mission, and you might not realize that was possible at that moment – but the scene is definitely present there. Maybe it was reintroduced for international releases?

Alex Smith

March 6, 2021 at 10:06 pm

*turns traitor. Stupid typos.

A. Freed

March 7, 2021 at 5:25 am

For folks interested, the cut Hobbes scene Alex Smith mentions is available (along with various other bits of cut footage) here: https://www.wcnews.com/holovids/lost_wing3.shtml

Alex Smith

March 7, 2021 at 5:36 pm

That is interesting Sebastian. It was definitely not in the US release, so they must have snuck it back in.

Darren

March 8, 2021 at 5:04 pm

I had the US PC version and absolutely remember that cutscene. Did they patch it back in or was it updated in later releases?

Darren

March 8, 2021 at 5:26 pm

Ok, so after doing some digging, it looks like WC3 was re-released with a “Electronic Arts Presents CD-ROM Classics” tag at the bottom. If you bought that version it looks like it had the Hobbes defection explanation cutscene in it.

John

March 7, 2021 at 10:57 pm

The shooting mechanics in Privateer–and I am forced to assume also in Wing Commander and Wing Commander II–are awful. It is almost impossible to get a gun kill in Privateer if your ship is not equipped with an advanced targeting system. The game’s sprite-based graphics make it difficult to judge your target’s actual distance and heading and leading the target properly is almost impossible. The X-Wing series, having proper 3D graphics, does not suffer from this problem. You don’t need a computer-controlled targeting reticule to hit an enemy ship in X-Wing or Tie Fighter the way you do in Privateer.

It’s possible that the 3D Wing Commanders did it better. It would be hard to do worse. It’s also possible that you always have that advanced targeting system in Wing Commander and Wing Commander II. I wouldn’t know. But as much as I love Privateer for letting me tool around the galaxy and do my own thing in my personally customized space ship I cannot by any stretch of the imagination call the shooting mechanics good.

Nils

March 8, 2021 at 7:19 pm

Wing Commander doesn’t have a lead indicator at all. I think WC2 does, but only on select ships? It’s not actually that tough though, as the games are pretty lenient about hitting targets, and enemy fighters are not that quick. Now, I myself haven’t played Privateer, but I’d say that shooting is actually more difficult in WCIII and IV, especially against fast-moving enemies like Darkets and Arrows, who are quite agile and change directions erratically. The aiming reticule moves around so quickly that it hardly helps at all. This, of course, is of no consequence when flying the Excalibur superfighter, which features an auto-aiming system…

Buck

March 8, 2021 at 10:09 pm

I recently played through Privateer with keyboard controls, I had no trouble destroying enemies with guns only and without advanced targeting. It helps having enough energy to fire a few “homing” shots. I think I missed more shots with targeting because it makes you just point at the target indicator and fire, but if the target is maneuvering your shots will just miss.

I’m not sure if playing with the keyboard was still a sensible option with WC 3.

John

March 9, 2021 at 11:41 am

I don’t know what you mean by “homing shots”. To the best of my recollection, there are no guns whose projectiles track enemy ships. There are a couple of different kinds of homing missiles, however, and these are in my experience the only reliable way to get kills in the early game before you can afford an advanced targeting system for your guns.

Bryan

March 6, 2021 at 6:29 pm

I’ve never played WCIII (I was also a Privateer fan) but I just want to alert you that the lovely mobile mode on the site seems to have conked out. It’s just showing the full website on my phone as of the past few days.

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2021 at 8:47 pm

It seems my caching plug-in was bumping heads with my mobile plug-in. Should be fixed now.

Adamantyr

March 7, 2021 at 7:47 pm

Wing Commander III was definitely one of those games that was a huge hit in it’s time, but it doesn’t hold up today at all. It rather reminds me of the movie “Batman Forever”… we all enjoyed it at the time, but now it just makes us cringe for a myriad of reasons.

The best way to play the first three WC games is with the Kilrathi Saga, which had the first three games fully playable in modern Windows. It even gives you “virtual cockpit” options for all of the games, which is really nice. It’s super rare though, only 20,000 copies were made.

Tom Wilson was so fun in this one though, and the sequels. I actually met him at a con a few years ago and had him sign a WC3 poster.

Svein-Frode

March 8, 2021 at 8:17 am

You pretty much hit the nail on the head with this one as far as I’m concerned. I was never a big fan of space games, but I bought into the hype when this came out. It was a cool idea – on paper. We were a bunch of friends that sat around and played through it together. I remember the cut scenes became old really fast, and there really wasn’t much of a story. I still have the game, but rather than play it again, I just fast forwarded through a “movie” version on youtube. Under a Killing Moon on the other hand is worth a replay.

BoardGameNut

March 8, 2021 at 5:27 pm

Talk a trip down memory lane. WC was one of my favorite series. I remember enjoying this iteration a lot, and I would have to agree that the first one really was the best. Personally, I was more interested in the space sim side of things and felt like the story got more in the way :) I would much prefer to play 1 & 2 over this and purchased them again. Ever time I see WC3 go on sale at GOG for a buck fifty, I can’t bring myself to buy it. I did finish WC3 and I didn’t have any trouble with the trench run like other people mentioned. WC4 was a rehash in some ways was even less interesting where I can barely remember the storyline with Admiral Tolwyn being the big bad guy. I bought WC5 and never made it very far. It was forgettable.

Michael

March 8, 2021 at 11:17 pm

“With commanding officiers like these”

–> officers

Jimmy Maher

March 9, 2021 at 7:54 am

Thanks!

Tim Kaiser

March 10, 2021 at 4:10 am

Oh man, watching those FMV clips put me to sleep. Is it the script? Or the acting? Or both? Or maybe it’s because they are just dialogue scenes with no camera movement, no interesting music and featuring characters and a story that I don’t know and am not interested in.

However, I do have memories of playing one of these FMV Wing Commander games at my cousin’s house decades ago. I think it was WCIV. I also have the memory of generic movie clips followed by generic space combat. Even as a kid at the time, the game did not interest me.

I am a bit nostalgic towards this era of games though. FMV was a big breakthrough and the often cheesy acting by mostly amateur actors could be fun. In this case, it feels like it’s a bunch of bored professionals doing the bare minimum for a paycheck (Tom Wilson excluded).

CV

March 10, 2021 at 4:07 pm

You looked at WC3’s historical context but seem to have missed an important part of it. In 1993, space opera scifi in pop culture included:

1. The revival of Star Wars with Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire (Thrawn) trilogy.

2. Star Trek The Next Generation in its mature phase.

3. Star Trek DS9.

4. Babylon 5.

WC3 comes out in this time period and lets gamers play a badass starfighter pilot, not unlike their favorite characters. And the experience takes place not just in the cockpit, but outside it, and contains other characters to interact with, along with a story whose linearity is easy to ignore with just a bit of suspension of disbelief (at least on first play-through). There’s an immersive role-playing element to WC3 that I don’t think existed before (and I certainly didn’t experience at the time). And the whole thing looks like TV and not just pixelated Blue Hair. And Mark fucking Hamill is the player’s avatar! That works way better than you give it credit for.

I agree that the two individual components of WC3 leave much to be desired, but separating and deconstructing them, and concluding that it’s a bad game “in the abstract” sells it woefully short.

Comchia

March 11, 2021 at 2:26 am

While I’m a big fan of the Wing Commander franchise, 3 included (got me through a rough period!), nonetheless, I enjoyed reading your perspective of this game, both in the game itself, and what it represented in the wider industry as a whole. This, and 4, probably have my favourite cutscenes of any game. I particularly loved Jason Bernard’s performance, and wish he was still around to deliver more of that kind of energy.

For straight up space combat, X-Wing/TIE Fighter still remain my all time favourites, especially in how military-sim they feel.

Patryk

March 11, 2021 at 11:30 am

I was definitely in the target group for the WC series and even had an early Pentium PC with CD ROM so I was able to experience WC III and IV at that time. But I definitely agree with Jimmy and virtually everyone else here. WC III was just a simple and boring shooter in comparison with TIE Fighter with its highly complex and immersive mission design. When it comes to the multimedia thing, the TIE Fighter CD ROM edition includes voiceover in mission briefings read by Guy Siner, a British actor that is widely known for most Europeans as Lt. Gruber from the Allo Allo series. It is just so cool to hear Lt. Gruber, with his distinctive slightly feminine voice, bragging about some high-tech Empire weaponry. This voiceover and Mark Hamill/Tim Curry duo in Gabriel Knight are my favorite pieces of multimedia from the mid-1990s.

Lt. Nitpicker

March 12, 2021 at 6:54 pm

The second sentence in this block of text kinda feels like it’s missing a word.

Jimmy Maher

March 12, 2021 at 9:27 pm

As intended, thanks.

DZ-Jay

April 23, 2023 at 2:37 pm

Perhaps a strategically placed comma may help. As it stands, it took me three read-throughs to finally get what you were trying to say. ;)

>> “Rather, credit him and the rest of Origin …”

Also, it could use the re-introduction of the pronoun, for continuity and context, if in fact you meant it that way; or else it reads as an imperative clause commanding the reader to offer credit himself, which seems inconsistent with the first sentence.

>> “Rather, I credit him and the rest of Origin …”

I appreciate that you may want to stick to the current text as your own personal flair, but sometimes legibility and intelligibility should trump flourish for the sake of the reader.

Just a suggestion …

dZ.

Richard Smith

March 14, 2021 at 3:11 am

I have to thank you. I had this old vivid memory of a bad CGI cat in a movie. I could remember nothing else about the movie, and though I went looking for it occasionally, I could never find it. Turns out it was the Wing Commander movie. Thanks for helping me solve that mystery, lol.

Max Kowarski

April 15, 2021 at 9:51 am

Typo: Tolywyn should be Tolwyn in the caption for the second image.

> If you can look past the inherent cheesiness of pixelated human actors overlaid upon computer-generated backgrounds, you can see some competent directing and acting going on.

So not unlike the endless MCU, Star Wars, Pirates of the Caribbean, etc stuff that Hollywood did for the past 15-20 years now, eh? So, in a sense, it WAS really a taste of things to come. Though I admit, the degree of cosplay involved got progressively higher over the years.

Jimmy Maher

April 15, 2021 at 9:57 am

Thanks!

Lhexa

April 24, 2021 at 1:42 pm

My editor senses just went haywire. Let me suggest a small edit:

“It’s widely known by those who are interested in the history of gaming that the videogame industry was hauled into a United States Senate hearing on December 9, 1993, to address concerns about the violence and sex to be found in its products. Yet the specifics of what was said on that occasion have been less widely disseminated.”

–>

“The videogame industry was hauled into a United States Senate hearing on December 9, 1993, to address concerns about the violence and sex to be found in its products. The specifics of what was said on that crucial occasion have not been widely disseminated.”

Lhexa

April 26, 2021 at 8:36 pm

Anyway. I’m not the only person who took a slow, nonviolent approach through the world of pagan, and was thus able to experience the interlude in which the previous pantheon talks about what Pagan was before the Guardian came. I know I’m not the only one, because I had to follow a walkthrough in order to uncover the route. :P I’m also one of the few people who seems to remember that after unleashing the Titans on the world, you hunt them down one by one and kill them.

Wolfeye Mox

August 12, 2021 at 11:18 pm

The 90s is an era of games I kinda skipped. I had an Apple 2 E, with a lot of 80s games like Defender and F-15 Strike Eagle, thanks to my dad getting it used during the 90s. But, my family didn’t get a PC capable of running games until 2000, with Windows ME, I had to be picky about what I got, thanks to lack of funds, system requirements, and the fact it was the family PC. I had to clear buying Halo with my dad when I turned 17. Wasn’t until I had a job and money I could buy my own games I really got into PC games, and that was probably in my early or mid 20s in the early 2000s.

So, I missed out on Wing Commander 3. Seems like I might want to look it up on YouTube, but give actually playing it a miss. I’ve got Wing Commander 4 on gog, but I haven’t gotten around to playing it yet. Now I’m wondering if the space sim part, the whole reason I have for playing it, is any good, because they went and put a movie in it, too. Ugh.

Anyway, been enjoying reading your articles about games again. It’s cool to read the history of video games, even if it’s about ones I’ve not, and might never, play.

Kevin McHugh

October 5, 2021 at 4:01 am

A belated congratulations on ten years of writing this blog, Jimmy! This is quite a feat.

Jimmy Maher

October 6, 2021 at 6:21 am

Thank you! It seems longer in some ways, shorter in others…

Jonathan O

January 18, 2022 at 5:49 pm

Just seen this: “The actor inside a Kilrathi costume get some much-needed fresh air…” (I’m not sure from the photo whether actor or get is missing an s).

Jimmy Maher

January 20, 2022 at 10:29 pm

Thanks!