One day in late 1992, a trim older man with a rigid military bearing visited Sierra Online’s headquarters in Oakhurst, California. From his appearance, and from the way that Sierra’s head Ken Williams fawned over him, one might have assumed him to be just another wealthy member of the investment class, a group that Williams had been forced to spend a considerable amount of time wooing ever since he had taken his company public four years earlier. But that turned out not to be the case. As Williams began to introduce his guest to some of his employees, he described him as Sierra’s newest game designer, destined to make the fourth game in the Police Quest series. It seemed an unlikely role based on the new arrival’s appearance and age alone.

Yet ageism wasn’t sufficient to explain the effect he had on much of Sierra’s staff. Josh Mandel, a sometime stand-up comic who was now working for Sierra as a writer and designer, wanted nothing whatsoever to do with him: “I wasn’t glad he was there. I just wanted him to go away as soon as possible.” Gano Haine, who was hard at work designing the environmental-themed EcoQuest: Lost Secret of the Rainforest, reluctantly accepted the task of showing the newcomer some of Sierra’s development tools and processes. He listened politely enough, although it wasn’t clear how much he really understood. Then, much to her relief, the boss swept him away again.

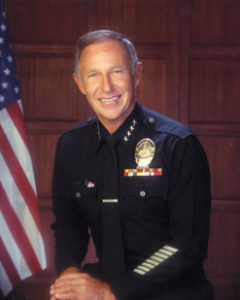

The man who had prompted such discomfort and consternation was arguably the most politically polarizing figure in the United States at the time: Daryl F. Gates, the recently resigned head of the Los Angeles Police Department. Eighteen months before, four of his white police officers had brutally beaten a black man — an unarmed small-time lawbreaker named Rodney King — badly enough to break bones and teeth. A private citizen had captured the incident on videotape. One year later, after a true jury of their peers in affluent, white-bread Simi Valley had acquitted the officers despite the damning evidence of the tape, the Los Angeles Riots of 1992 had begun. Americans had watched in disbelief as the worst civil unrest since the infamously restive late 1960s played out on their television screens. The scene looked like a war zone in some less enlightened foreign country; this sort of thing just doesn’t happen here, its viewers had muttered to themselves. But it had happened. The final bill totaled 63 people killed, 2383 people injured, and more than $1 billion in property damage.

The same innocuous visage that was now to become Sierra’s newest game designer had loomed over all of the scenes of violence and destruction. Depending on whether you stood on his side of the cultural divide or the opposite one, the riots were either the living proof that “those people” would only respond to the “hard-nosed” tactics employed by Gates’s LAPD, or the inevitable outcome of decades of those same misguided tactics. The mainstream media hewed more to the latter narrative. When they weren’t showing the riots or the Rodney King tape, they played Gates’s other greatest hits constantly. There was the time he had said, in response to the out-sized numbers of black suspects who died while being apprehended in Los Angeles, that black people were more susceptible to dying in choke holds because their arteries didn’t open as fast as those of “normal people”; the time he had said that anyone who smoked a joint was a traitor against the country and ought to be “taken out and shot”; the time when he had dismissed the idea of employing homosexuals on the force by asking, “Who would want to work with one?”; the time when his officers had broken an innocent man’s nose, and he had responded to the man’s complaint by saying that he was “lucky that was all he had broken”; the time he had called the LAPD’s peers in Philadelphia “an inspiration to the nation” after they had literally launched an airborne bombing raid on a troublesome inner-city housing complex, killing six adults and five children and destroying 61 homes. As the mainstream media was reacting with shock and disgust to all of this and much more, right-wing radio hosts like Rush Limbaugh trotted out the exact same quotes, but greeted them with approbation rather than condemnation.

All of which begs the question of what the hell Gates was doing at Sierra Online, of all places. While they were like most for-profit corporations in avoiding overly overt political statements, Sierra hardly seemed a bastion of reactionary sentiment or what the right wing liked to call “family values.” Just after founding Sierra in 1980, Ken and Roberta Williams had pulled up stakes in Los Angeles and moved to rural Oakhurst more out of some vague hippie dream of getting back to the land than for any sound business reason. As was known by anyone who’d read Steven Levy’s all-too-revealing book Hackers, or seen a topless Roberta on the cover of a game called Softporn, Sierra back in those days had been a nexus of everything the law-and-order contingent despised: casual sex and hard drinking, a fair amount of toking and even the occasional bit of snorting. (Poor Richard Garriott of Ultima fame, who arrived in this den of iniquity from a conservative neighborhood of Houston inhabited almost exclusively by straight-arrow astronauts like his dad, ran screaming from it all after just a few months; decades later, he still sounds slightly traumatized when he talks about his sojourn in California.)

It was true that a near-death experience in the mid-1980s and an IPO in 1988 had done much to change life at Sierra since those wild and woolly early days. Ken Williams now wore suits and kept his hair neatly trimmed. He no longer slammed down shots of tequila with his employees to celebrate the close of business on a Friday, nor made it his personal mission to get his nerdier charges laid; nor did he and Roberta still host bathing-suit-optional hot-tub parties at their house. But when it came to the important questions, Williams’s social politics still seemed diametrically opposed to those of Daryl Gates. For example, at a time when even the mainstream media still tended to dismiss concerns about the environment as obsessions of the Loony Left, he’d enthusiastically approved Gano Haines’s idea for a series of educational adventure games to teach children about just those issues. When a 15-year-old who already had the world all figured out wrote in to ask how Sierra could “give in to the doom-and-gloomers and whacko commie liberal environmentalists” who believed that “we can destroy a huge, God-created world like this,” Ken’s brother John Williams — Sierra’s marketing head — offered an unapologetic and cogent response: “As long as we get letters like this, we’ll keep making games like EcoQuest.”

So, what gave? Really, what was Daryl Gates doing here? And how had this figure that some of Ken Williams’s employees could barely stand to look at become connected with Police Quest, a slightly goofy and very erratic series of games, but basically a harmless one prior to this point? To understand how all of these trajectories came to meet that day in Oakhurst, we need to trace each back to its point of origin.

Perhaps the kindest thing we can say about Daryl Gates is that he was, like the young black men he and his officers killed, beat, and imprisoned by the thousands, a product of his environment. He was, the sufficiently committed apologist might say, merely a product of the institutional culture in which he was immersed throughout his adult life. Seen in this light, his greatest sin was his inability to rise above his circumstances, a failing which hardly sets him apart from the masses. One can only wish he had been able to extend to the aforementioned black men the same benefit of the doubt which other charitable souls might be willing to give to him.

Long before he himself became the head of the LAPD, Gates was the hand-picked protege of William Parker, the man who has gone down in history as the architect of the legacy Gates would eventually inherit. At the time Parker took control of it in 1950, the LAPD was widely regarded as the most corrupt single police force in the country, its officers for sale to absolutely anyone who could pay their price; they went so far as to shake down ordinary motorists for bribes at simple traffic stops. To his credit, Parker put a stop to all that. But to his great demerit, he replaced rank corruption on the individual level with an us-against-them form of esprit de corps — the “them” here being the people of color who were pouring into Los Angeles in ever greater numbers. Much of Parker’s approach was seemingly born of his experience of combat during World War II. He became the first but by no means the last LAPD chief to make comparisons between his police force and an army at war, without ever considering whether the metaphor was really appropriate.

Parker was such a cold fish that Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, who served as an LAPD officer during his tenure as chief, would later claim to have modeled the personality of the emotionless alien Spock on him. And yet, living as he did in the epicenter of the entertainment industry — albeit mostly patrolling the parts of Los Angeles that were never shown by Hollywood — Parker was surprisingly adept at manipulating the media to his advantage. Indeed, he became one of those hidden players who sometimes shape media narratives without anyone ever quite realizing that they’re doing so. He served as a consultant for the television show Dragnet, the first popular police drama, which all but placed a halo above the heads of the officers of the LAPD. The many shows that followed it cemented a pernicious cliché of the “ideal” cop that can still be seen, more than half a century later, on American television screens every evening: the cop as tough crusader who has to knock a few heads sometimes and bend or break the rules to get around the pansy lawyers, but who does it all for a noble cause, guided by an infallible moral compass that demands that he protect the “good people” of his city from the irredeemably bad ones by whatever means are necessary. Certainly Daryl Gates would later benefit greatly from this image; it’s not hard to believe that even Ken Williams, who fancied himself something of a savvy tough guy in his own right, was a little in awe of it when he tapped Gates to make a computer game.

But this wasn’t the only one of Chief Parker’s innovations that would come to the service of the man he liked to describe as the son he’d never had. Taking advantage of a city government desperate to see a cleaned-up LAPD, Parker drove home policies that made the city’s police force a veritable fiefdom unto itself, its chief effectively impossible to fire. The city council could only do so “for cause” — i.e., some explicit failure on the chief’s part. This sounded fair enough — until one realized that the chief got to write his own evaluation every year. Naturally, Parker and his successors got an “excellent” score every time, and thus the LAPD remained for decades virtually impervious to the wishes of the politicians and public it allegedly served.

As Parker’s tenure wore on, tension spiraled in the black areas of Los Angeles, the inevitable response to an utterly unaccountable LAPD’s ever more brutal approach to policing. It finally erupted in August of 1965 in the form of the Watts Riots, the great prelude to the riots of 1992: 34 deaths, $40 million in property damage in contemporary dollars. For Daryl Gates, who watched it all take place by Parker’s side, the Watts Riots became a formative crucible. “We had no idea how to deal with this,” he would later write. “We were constantly ducking bottles, rocks, knives, and Molotov cocktails. It was random chaos. We did not know how to handle guerrilla warfare.” Rather than asking himself how it had come to this in the first place and how such chaos might be prevented in the future, he asked how the LAPD could be prepared to go toe to toe with future rioters in what amounted to open warfare on city streets.

Chief Parker died the following year, but Gates’s star remained on the ascendant even without his patron. He came up with the idea of a hardcore elite force for dealing with full-on-combat situations, a sort of SEAL team of police. Of course, the new force would need an acronym that sounded every bit as cool as its Navy inspiration. He proposed SWAT, for “Special Weapons Attack Teams.” When his boss balked at such overtly militaristic language, he said that it could stand for “Special Weapons and Tactics” instead. “That’s fine,” said his boss.

Gates and his SWAT team had their national coming-out party on December 6, 1969, when they launched an unprovoked attack upon a hideout of the Black Panthers, a well-armed militia composed of black nationalists which had been formed as a response to earlier police brutality. Logistically and practically, the raid was a bit of a fiasco. The attackers got discombobulated by an inaccurate map of the building and very nearly got themselves hemmed into a cul de sac and massacred. (“Oh, God, we were lucky,” said one of them later.) What was supposed to have been a blitzkrieg-style raid devolved into a long stalemate. The standoff was broken only when Gates managed to requisition a grenade launcher from the Marines at nearby Camp Pendleton and started lobbing explosives into the building; this finally prompted the Panthers to surrender. By some miracle, no one on either side got killed, but the Panthers were acquitted in court of most charges on the basis of self-defense.

Yet the practical ineffectuality of the operation mattered not at all to the political narrative that came to be attached to it. The conservative white Americans whom President Nixon loved to call “the silent majority” — recoiling from the sex, drugs, and rock and roll of the hippie era, genuinely scared by the street violence of the last several years — applauded Gates’s determination to “get tough” with “those people.” For the first time, the names of Daryl Gates and his brainchild of SWAT entered the public discourse beyond Los Angeles.

In May of 1974, the same names made the news in a big way again when the SWAT team was called in to subdue the Symbionese Liberation Army, a radical militia with a virtually incomprehensible political philosophy, who had recently kidnapped and apparently converted to their cause the wealthy heiress Patty Hearst. After much lobbying on Gates’s part, his team got the green light to mount a full frontal assault on the group’s hideout. Gates and his officers continued to relish military comparisons. “Here in the heart of Los Angeles was a war zone,” he later wrote. “It was like something out of a World War II movie, where you’re taking the city from the enemy, house by house.” More than 9000 rounds of ammunition were fired by the two sides. But by now, the SWAT officers did appear to be getting better at their craft. Eight members of the militia were killed — albeit two of them unarmed women attempting to surrender — and the police officers received nary a scratch. Hearst herself proved not to be inside the hideout, but was arrested shortly after the battle.

The Patty Hearst saga marked the last gasp of a militant left wing in the United States; the hippies of the 1960s were settling down to become the Me Generation of the 1970s. Yet even as the streets were growing less turbulent, increasingly militaristic rhetoric was being applied to what had heretofore been thought of as civil society. In 1971, Nixon had declared a “war on drugs,” thus changing the tone of the discourse around policing and criminal justice markedly. Gates and SWAT were the perfect mascots for the new era. The year after the Symbionese shootout, ABC debuted a hit television series called simply S.W.A.T. Its theme song topped the charts; there were S.W.A.T. lunch boxes, action figures, board games, and jigsaw puzzles. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to be like Daryl Gates and the LAPD — not least their fellow police officers in other cities: by July of 1975, there were 500 other SWAT teams in the United States. Gates embraced his new role of “America’s cop” with enthusiasm.

In light of his celebrity status in a city which worships celebrity, it was now inevitable that Gates would become the head of the LAPD just as soon as the post opened up. He took over in 1978; this gave him an even more powerful nationwide bully pulpit. In 1983, he applied some of his clout to the founding of a program called DARE in partnership with public schools around the country. The name stood for “Drug Abuse Resistance Education”; Gates really did have a knack for snappy acronyms. His heart was perhaps in the right place, but later studies, conducted only after the spending of hundreds of millions in taxpayer dollars, would prove the program’s strident rhetoric and almost militaristic indoctrination techniques to be ineffective.

Meanwhile, in his day job as chief of police, Gates fostered an ever more toxic culture that viewed the streets as battlegrounds, that viewed an ass beating as the just reward of any black man who failed to treat a police officer with fawning subservience. In 1984, the Summer Olympics came to Los Angeles, and Gates used the occasion to convince the city council to let him buy armored personnel carriers — veritable tanks for the city streets — in the interest of “crowd control.” When the Olympics were over, he held onto them for the purpose of executing “no-knock” search warrants on suspected drug dens. During the first of these, conducted with great fanfare before an invited press in February of 1985, Gates himself rode along as an APC literally drove through the front door of a house after giving the occupants no warning whatsoever. Inside they found two shocked women and three children, with no substance more illicit than the bowls of ice cream they’d been eating. To top it all off, the driver lost control of the vehicle on a patch of ice whilst everyone was sheepishly leaving the scene, taking out a parked car.

Clearly Gates’s competence still tended not to entirely live up to his rhetoric, a discrepancy the Los Angeles Riots would eventually highlight all too plainly. But in the meantime, Gates was unapologetic about the spirit behind the raid: “It frightened even the hardcore pushers to imagine that at any moment a device was going to put a big hole in their place of business, and in would march SWAT, scattering flash-bangs and scaring the hell out of everyone.” This scene would indeed be played out many times over the remaining years of Gates’s chiefdom. But then along came Rodney King of all people to inadvertently bring about his downfall.

King was a rather-slow-witted janitor and sometime petty criminal with a bumbling reputation on the street. He’d recently done a year in prison after attempting to rob a convenience store with a tire iron; over the course of the crime, the owner of the store had somehow wound up disarming him, beating him over the head with his own weapon, and chasing him off the premises. He was still on parole for that conviction on the evening of March 3, 1991, when he was spotted by two LAPD officers speeding down the freeway. King had been drinking, and so, seeing their patrol car’s flashing lights in his rear-view mirror, he decided to make a run for it. He led what turned into a whole caravan of police cars on a merry chase until he found himself hopelessly hemmed in on a side street. The unarmed man then climbed out of his car and lay face down on the ground, as instructed. But then he stood up and tried to make a break for it on foot, despite being completely surrounded. Four of the 31 officers on the scene now proceeded to knock him down and beat him badly enough with their batons and boots to fracture his face and break one of his ankles. Their colleagues simply stood and watched at a distance.

Had not a plumber named George Holliday owned an apartment looking down on that section of street, the incident would doubtless have gone down in the LAPD’s logs as just another example of a black man “resisting arrest” and getting regrettably injured in the process. But Holliday was there, standing on his balcony — and he had a camcorder to record it all. When he sent his videotape to a local television station, its images of the officers taking big two-handed swings against King’s helpless body with their batons ignited a national firestorm. The local prosecutor had little choice but to bring the four officers up on charges.

The tactics of Daryl Gates now came under widespread negative scrutiny for the first time. Although he claimed to support the prosecution of the officers involved, he was nevertheless blamed for fostering the culture that had led to this incident, as well as the many others like it that had gone un-filmed. At long last, reporters started asking the black residents of Los Angeles directly about their experiences with the LAPD. A typical LAPD arrest, said one of them, “basically consisted of three or four cops handcuffing a person, and just literally beating him, often until unconscious… punching, beating, kicking.” A hastily assembled city commission produced pages and pages of descriptions of a police force run amok. “It is apparent,” the final report read, “that too many LAPD patrol officers view citizens with resentment and hostility.” In response, Gates promised to retire “soon.” Yet, as month after month went by and he showed no sign of fulfilling his promise, many began to suspect that he still had hopes of weathering the storm.

At any rate, he was still there on April 29, 1992. That was the day his four cops were acquitted in Simi Valley, a place LAPD officers referred to as “cop heaven”; huge numbers of them lived there. Within two hours after the verdict was announced, the Los Angeles Riots began in apocalyptic fashion, as a mob of black men pulled a white truck driver out of his cab and all but tore him limb from limb, all under the watchful eye of a helicopter that was hovering overhead and filming the carnage.

Tellingly, Gates happened to be speaking to an adoring audience of white patrons in the wealthy suburb of Brentwood at the very instant the riots began. As the violence continued, this foremost advocate of militaristic policing seemed bizarrely paralyzed. South Los Angeles burned, and the LAPD did virtually nothing about it. The most charitable explanation had it that Gates, spooked by the press coverage of the previous year, was terrified of how white police officers subduing black rioters would play on television. A less charitable one, hewed to by many black and liberal commentators, had it that Gates had decided that these parts of the city just weren’t worth saving — had decided to just let the rioters have their fun and burn it all down. But the problem, of course, was that in the meantime many innocent people of all colors were being killed and wounded and seeing their property go up in smoke. Finally, the mayor called in the National Guard to quell the rioting while Gates continued to sit on his hands.

Asked afterward how the LAPD — the very birthplace of SWAT — had allowed things to get so out of hand, Gates blamed it on a subordinate: “We had a lieutenant down there who just didn’t seem to know what to do, and he let us down.” Not only was this absurd, but it was hard to label as anything other than moral cowardice. It was especially rich coming from a man who had always preached an esprit de corps based on loyalty and honor. The situation was now truly untenable for him. Incompetence, cowardice, racism, brutality… whichever charge or charges you chose to apply, the man had to go. Gates resigned, for real this time, on June 28, 1992.

Yet he didn’t go away quietly. Gates appears to have modeled his post-public-service media strategy to a large extent on that of Oliver North, a locus of controversy for his role in President Ronald Reagan’s Iran-Contra scandal who had parlayed his dubious celebrity into the role of hero to the American right. Gates too gave a series of angry, unrepentant interviews, touted a recently published autobiography, and even went North one better when he won his own radio show which played in close proximity to that of Rush Limbaugh. And then, when Ken Williams came knocking, he welcomed that attention as well.

But why would Williams choose to cast his lot with such a controversial figure, one whose background and bearing were so different from his own? To begin to understand that, we need to look back to the origins of the adventure-game oddity known as Police Quest.

Ken Williams, it would seem, had always had a fascination with the boys in blue. One day in 1985, when he learned from his hairdresser that her husband was a California Highway Patrol officer on administrative leave for post-traumatic stress, his interest was piqued. He invited the cop in question, one Jim Walls, over to his house to play some racquetball and drink some beer. Before the evening was over, he had started asking his guest whether he’d be interested in designing a game for Sierra. Walls had barely ever used a computer, and had certainly never played an adventure game on one, so he had only the vaguest idea what his new drinking buddy was talking about. But the only alternative, as he would later put it, was to “sit around and think” about the recent shootout that had nearly gotten him killed, so he agreed to give it a go.

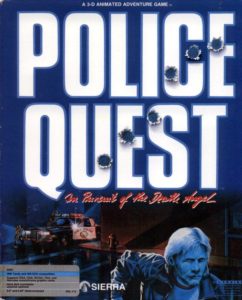

The game which finally emerged from that conversation more than two years later shows the best and the worst of Sierra. On the one hand, it pushed a medium that was usually content to wallow in the same few fictional genres in a genuinely new direction. In a pair of articles he wrote for Computer Gaming World magazine, John Williams positioned Police Quest: In Pursuit of the Death Angel at the forefront of a new wave of “adult” software able to appeal to a whole new audience, noting how it evoked Joseph Wambaugh rather than J.R.R. Tolkien, Hill Street Blues rather than Star Wars. Conceptually, it was indeed a welcome antidote to a bad case of tunnel vision afflicting the entire computer-games industry.

In practical terms, however, it was somewhat less inspiring. The continual sin of Ken Williams and Sierra throughout the company’s existence was their failure to provide welcome fresh voices like that of Jim Walls with the support network that might have allowed them to make good games out of their well of experiences. Left to fend for himself, Walls, being the law-and-order kind of guy he was, devised the most pedantic adventure game of all time, one which played like an interactive adaptation of a police-academy procedure manual — so much so, in fact, that a number of police academies around the country would soon claim to be employing it as a training tool. The approach is simplicity itself: in every situation, if you do exactly what the rules of police procedure that are exhaustively described in the game’s documentation tell you to do, you get to live and go on to the next scene. If you don’t, you die. It may have worked as an adjunct to a police-academy course, but it’s less compelling as a piece of pure entertainment.

Although it’s an atypical Sierra adventure game in many respects, this first Police Quest nonetheless opens with what I’ve always considered to be the most indelibly Sierra moment of all. The manual has carefully explained — you did read it, right? — that you must walk all the way around your patrol car to check the tires and lights and so forth every time you’re about to drive somewhere. And sure enough, if you fail to do so before you get into your car for the first time, a tire blows out and you die as soon as you drive away. But if you do examine your vehicle, you find no evidence of a damaged tire, and you never have to deal with any blow-out once you start driving. The mask has fallen away to reveal what we always suspected: that the game actively wants to kill you, and is scheming constantly for a way to do so. There’s not even any pretension left of fidelity to a simulated world — just pure, naked malice. Robb Sherwin once memorably said that “Zork hates its player.” Well, Zork‘s got nothing on Police Quest.

Nevertheless, Police Quest struck a modest chord with Sierra’s fan base. While it didn’t become as big a hit as Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards, John Williams’s other touted 1987 embodiment of a new wave of “adult” games, it sold well enough to mark the starting point of another of the long series that were the foundation of Sierra’s marketing strategy. Jim Walls designed two sequels over the next four years, improving at least somewhat at his craft in the process. (In between them, he also came up with Code-Name: Iceman, a rather confused attempt at a Tom Clancy-style techno-thriller that was a bridge too far even for most of Sierra’s loyal fans.)

But shortly after completing Police Quest 3: The Kindred, Walls left Sierra along with a number of other employees to join Tsunami Media, a new company formed right there in Oakhurst by Edmond Heinbockel, himself a former chief financial officer for Sierra. With Walls gone, but his Police Quest franchise still selling well enough to make another entry financially viable, the door was wide open — as Ken Williams saw it, anyway — for one Daryl F. Gates.

Williams began his courtship of the most controversial man in the United States by the old-fashioned expedient of writing him a letter. Gates, who claimed never even to have used a computer, much less played a game on one, was initially confused about what exactly Williams wanted from him. Presuming Williams was just one of his admirers, he sent a letter back asking for some free games for some youngsters who lived across the street from him. Williams obliged in calculated fashion, with the three extant Police Quest games. From that initial overture, he progressed to buttering Gates up over the telephone.

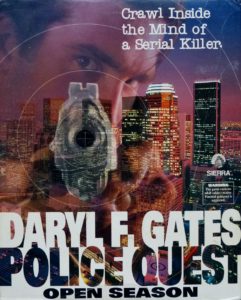

As the relationship moved toward the payoff stage, some of his employees tried desperately to dissuade him from getting Sierra into bed with such a figure. “I thought it’s one thing to seek controversy, but another thing to really divide people,” remembers Josh Mandel. Mandel showed his boss a New York Times article about Gates’s checkered history, only to be told that “our players don’t read the New York Times.” He suggested that Sierra court Joseph Wambaugh instead, another former LAPD officer whose novels presented a relatively more nuanced picture of crime and punishment in the City of Angels than did Gates’s incendiary rhetoric; Wambaugh was even a name whom John Williams had explicitly mentioned in the context of the first Police Quest game five years before. But that line of attack was also hopeless; Ken Williams wanted a true mass-media celebrity, not a mere author who hid behind his books. So, Gates made his uncomfortable visit to Oakhurst and the contract was signed. Police Quest would henceforward be known as Daryl F. Gates’ Police Quest. Naturally, the setting of the series would now become Los Angeles; the fictional town of Lytton, the more bucolic setting of the previous three games in the series, was to be abandoned along with almost everything else previously established by Jim Walls.

Inside the company, a stubborn core of dissenters took to calling the game Rodney King’s Quest. Corey Cole, co-designer of the Quest for Glory series, remembers himself and many others being “horrified” at the prospect of even working in the vicinity of Gates: “As far as we were concerned, his name was mud and tainted everything it touched.” As a designer, Corey felt most of all for Jim Walls. He believed Ken Williams was “robbing Walls of his creation”: “It would be like putting Donald Trump’s name on a new Quest for Glory in today’s terms.”

Nevertheless, as the boss’s pet project, Gates’s game went inexorably forward. It was to be given the full multimedia treatment, including voice acting and the extensive use of digitized scenes and actors on the screen in the place of hand-drawn graphics. Indeed, this would become the first Sierra game that could be called a full-blown full-motion-video adventure, placing it at the vanguard of the industry’s hottest new trend.

Of course, there had never been any real expectation that Gates would roll up his sleeves and design a computer game in the way that Jim Walls had; celebrity did have its privileges, after all. Daryl F. Gates’ Police Quest: Open Season thus wound up in the hands of Tammy Dargan, a Sierra producer who, based on an earlier job she’d had with the tabloid television show America’s Most Wanted, now got the chance to try her hand at design. Corey Cole ironically remembers her as one of the most stereotypically liberal of all Sierra’s employees: “She strenuously objected to the use of [the word] ‘native’ in Quest for Glory III, and globally changed it to ‘indigenous.’ We thought that ‘the indigenous flora’ was a rather awkward construction, so we changed some of those back. But she was also a professional and did the jobs assigned to her.”

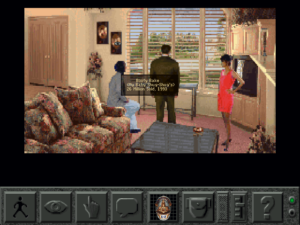

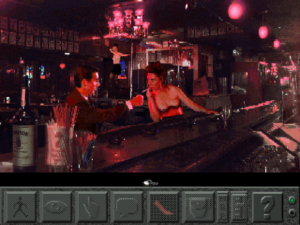

In this case, doing so would entail writing the script for a game about the mean streets of Los Angeles essentially alone, then sending it to Gates via post for “suggestions.” The latter did become at least somewhat more engaged when the time came for “filming,” using his connections to get Sierra inside the LAPD’s headquarters and even into a popular “cop bar.” Gates himself also made it into the game proper: restored to his rightful status of chief of police, he looks on approvingly and proffers occasional bits of advice as you work through the case. The CD-ROM version tacked on some DARE propaganda and a video interview with Gates, giving him yet one more opportunity to respond to his critics.

Contrary to the expectations raised both by the previous games in the series and the reputation of Gates, the player doesn’t take the role of a uniformed cop at all, but rather that of a plain-clothes detective. Otherwise, though, the game is both predictable in theme and predictably dire. Really, what more could one expect from a first-time designer working in a culture that placed no particular priority on good design, making a game that no one there particularly wanted to be making?

So, the dialog rides its banality to new depths for a series already known for clunky writing, the voice acting is awful — apparently the budget didn’t stretch far enough to allow the sorts of good voice actors that had made such a difference in King’s Quest VI — and the puzzle design is nonsensical. The plot, which revolves around a series of brutal cop killings for maximum sensationalism, wobbles along on rails through its ever more gruesome crime scenes and red-herring suspects until the real killer suddenly appears out of the blue in response to pretty much nothing which you’ve done up to that point. And the worldview the whole thing reflects… oh, my. The previous Police Quest games had hardly been notable for their sociological subtlety — “These kinds of people are actually running around out there, even if we don’t want to think about it,” Jim Walls had said of its antagonists — but this fourth game takes its demonization of all that isn’t white, straight, and suburban to what would be a comical extreme if it wasn’t so hateful. A brutal street gang, the in-game police files helpfully tell us, is made up of “unwed mothers on public assistance,” and the cop killer turns out to be a transvestite; his “deviancy” constitutes the sum total of his motivation for killing, at least as far as we ever learn.

One of the grisly scenes with which Open Season is peppered, reflecting a black-and-white — in more ways than one! — worldview where the irredeemably bad, deviant people are always out to get the good, normal people. Lucky we have the likes of Daryl Gates to sort the one from the other, eh?

Visiting a rap record label, one of a number of places where Sierra’s pasty-white writers get to try out their urban lingo. It goes about as well as you might expect.

Sierra throws in a strip bar for the sake of gritty realism. Why is it that television (and now computer-game) cops always have to visit these places — strictly in order to pursue leads, of course.

But the actual game of Open Season is almost as irrelevant to any discussion of the project’s historical importance today as it was to Ken Williams at the time. This was a marketing exercise, pure and simple. Thus Daryl Gates spent much more time promoting the game than he ever had making it. Williams put on the full-court press in terms of promotion, publishing not one, not two, but three feature interviews with him in Sierra’s news magazine and booking further interviews with whoever would talk to him. The exchanges with scribes from the computing press, who had no training or motivation for asking tough questions, went about as predictably as the game’s plot. Gates dismissed the outrage over the Rodney King tape as “Monday morning quarterbacking,” and consciously or unconsciously evoked Richard Nixon’s silent majority in noting that the “good, ordinary, responsible, quiet citizens” — the same ones who saw the need to get tough on crime and prosecute a war on drugs — would undoubtedly enjoy the game. Meanwhile Sierra’s competitors weren’t quite sure what to make of it all. “Talk about hot properties,” wrote the editors of Origin Systems’s internal newsletter, seemingly uncertain whether to express anger or admiration for Sierra’s sheer chutzpah. “No confirmation yet as to whether the game will ship with its own special solid-steel joystick” — a dark reference to the batons with which Gates’s officers had beat Rodney King.

In the end, though, the game generated decidedly less controversy than Ken Williams had hoped for. The computer-gaming press just wasn’t politically engaged enough to do much more than shrug their shoulders at its implications. And by the time it was released it was November of 1993, and Gates was already becoming old news for the mainstream press. The president of the Los Angeles Urban League did provide an obligingly outraged quote, saying that Gates “embodies all that is bad in law enforcement—the problems of the macho, racist, brutal police experience that we’re working hard to put behind us. That anyone would hire him for a project like this proves that some companies will do anything for the almighty dollar.” But that was about as good as it got.

There’s certainly no reason to believe that Gates’s game sold any better than the run-of-the-mill Sierra adventure, or than any of the Police Quest games that had preceded it. If anything, the presence of Gates’s name on the box seems to have put off more fans than it attracted. Rather than a new beginning, Open Season proved the end of the line for Police Quest as an adventure series — albeit not for Sierra’s involvement with Gates himself. The product line was retooled in 1995 into Daryl F. Gates’ Police Quest: SWAT, a “tactical simulator” of police work that played suspiciously like any number of outright war simulators. In this form, it found a more receptive audience and continued for years. Tammy Dargan remained at the reinvented series’s head for much of its run. History hasn’t recorded whether her bleeding-heart liberal sympathies went into abeyance after her time with Gates or whether the series remained just a slightly distasteful job she had to do.

Gates, on the other hand, got dropped after the first SWAT game. His radio show had been cancelled after he had proved himself to be a stodgy bore on the air, without even the modicum of wit that marked the likes of a Rush Limbaugh. Having thus failed in his new career as a media provocateur, and deprived forevermore of his old position of authority, his time as a political lightning rod had just about run out. What then was the use of Sierra continuing to pay him?

But then, Daryl Gates was never the most interesting person behind the games that bore his name. The hard-bitten old reactionary was always a predictable, easily known quantity, and therefore one with no real power to fascinate. Much more interesting was and is Ken Williams, this huge, mercurial personality who never designed a game himself but who lurked as an almost palpable presence in the background of every game Sierra ever released as an independent company. In short, Sierra was his baby, destined from the first to become his legacy more so than that of any member of his actual creative staff.

Said legacy is, like the man himself, a maze of contradictions resistant to easy judgments. Everything you can say about Ken Williams and Sierra, whether positive or negative, seems to come equipped with a “but” that points in the opposite direction. So, we can laud him for having the vision to say something like this, which accurately diagnosed the problem of an industry offering a nearly exclusive diet of games by and for young white men obsessed with Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings:

If you match the top-selling books, records, or films to the top-selling computer-entertainment titles, you’ll immediately notice differences. Where are the romance, horror, and non-fiction titles? Where’s military fiction? Where’s all the insider political stories? Music in computer games is infinitely better than what we had a few years back, but it doesn’t match what people are buying today. Where’s the country-western music? The rap? The reggae? The new age?

And yet Williams approached his self-assigned mission of broadening the market for computer games with a disconcerting mixture of crassness and sheer naivete. The former seemed somehow endemic to the man, no matter how hard he worked to conceal it behind high-flown rhetoric, while the latter signified a man who appeared never to have seriously thought about the nature of mass media before he started trying to make it for himself. “For a publisher to not publish a product which many customers want to buy is censorship,” he said at one point. No, it’s not, actually; it’s called curation, and is the right and perhaps the duty of every content publisher — not that there were lines of customers begging Sierra for a Daryl Gates-helmed Police Quest game anyway. With that game, Williams became, whatever else he was, a shameless wannabe exploiter of a bleeding wound at the heart of his nation — and he wasn’t even very good at it, as shown by the tepid reaction to his “controversial” game. His decision to make it reflects not just a moral failure but an intellectual misunderstanding of his audience so extreme as to border on the bizarre. Has anyone ever bought an adventure game strictly because it’s controversial?

So, if there’s a pattern to the history of Ken Williams and Sierra — and the two really are all but inseparable — it’s one of talking a good game, of being broadly right with the vision thing, but falling down in the details and execution. Another example from the horse’s mouth, describing the broad idea that supposedly led to Open Season:

The reason that I’m working with Chief Gates is that one of my goals has been to create a series of adventure games which accomplish reality through having been written by real experts. I have been calling this series of games the “Reality Role-Playing” series. I want to find the top cop, lawyer, airline pilot, fireman, race-car driver, politician, military hero, schoolteacher, white-water rafter, mountain climber, etc., and have them work with us on a simulation of their world. Chief Gates gives us the cop game. We are working with Emerson Fittipaldi to simulate racing, and expect to announce soon that Vincent Bugliosi, the lawyer who locked up Charles Manson, will be working with us to do a courtroom simulation. My goal is that products in the Reality Role-Playing series will be viewed as serious simulations of real-world events, not as games. If we do our jobs right, this will be the closest most of us will ever get to seeing the world through these people’s eyes.

The idea sounds magnificent, so much so that one can’t help but feel a twinge of regret that it never went any further than Open Season. Games excel at immersion, and their ability to let us walk a mile in someone else’s shoes — to become someone whose world we would otherwise never know — is still sadly underutilized.

I often — perhaps too often — use Sierra’s arch-rivals in adventure games LucasArts as my own baton with which to beat them, pointing out how much more thoughtful and polished the latter’s designs were. This remains true enough. Yet it’s also true that LucasArts had nothing like the ambition for adventure games which Ken Williams expresses here. LucasArts found what worked for them very early on — that thing being cartoon comedies — and rode that same horse relentlessly right up until the market for adventures in general went away. Tellingly, when they were asked to adapt Indiana Jones to an interactive medium, they responded not so much by adjusting their standard approach all that radically as by turning Indy himself into a cartoon character. Something tells me that Ken Williams would have taken a very different tack.

But then we get to the implementation of Williams’s ideas by Sierra in the form of Open Season, and the questions begin all over again. Was Daryl Gates truly, as one of the marketers’ puff pieces claimed, “the most knowledgeable authority on law enforcement alive?” Or was there some other motivation involved? I trust the answer is self-evident. (John Williams even admitted as much in another of the puff pieces: “[Ken] decided the whole controversy over Gates would ultimately help the game sell better.”) And then, why does the “reality role-playing” series have to focus only on those with prestige and power? If Williams truly does just want to share the lives of others with us and give us a shared basis for empathy and discussion, why not make a game about what it’s like to be a Rodney King?

Was it because Ken Williams was himself a racist and a bigot? That’s a major charge to level, and one that’s neither helpful nor warranted here — no, not even though he championed a distinctly racist and bigoted game, released under the banner of a thoroughly unpleasant man who had long made dog whistles to racism and bigotry his calling card. Despite all that, the story of Open Season‘s creation is more one of thoughtlessness than malice aforethought. It literally never occurred to Ken Williams that anyone living in South Los Angeles would ever think of buying a Sierra game; that territory was more foreign to him than that of Europe (where Sierra was in fact making an aggressive play at the time). Thus he felt free to exploit a community’s trauma with this distasteful product and this disingenuous narrative that it was created to engender “discussion.” For nothing actually to be found within Open Season is remotely conducive to civil discussion.

Williams stated just as he was beginning his courtship of Daryl Gates that, in a fast-moving industry, he had to choose whether to “lead, follow, or get out of the way. I don’t believe in following, and I’m not about to get out of the way. Therefore, if I am to lead then I have to know where I’m going.” And here we come to the big-picture thing again, the thing at which Williams tended to excel. His decision to work with Gates does indeed stand as a harbinger of where much of gaming was going. This time, though, it’s a sad harbinger rather than a happy one.

I believe that the last several centuries — and certainly the last several decades — have seen us all slowly learning to be kinder and more respectful to one another. It hasn’t been a linear progression by any means, and we still have one hell of a long way to go, but it’s hard to deny that it’s occurred. (Whatever the disappointments of the last several years, the fact remains that the United States elected a black man as president in 2008, and has finally accepted the right of gay people to marry even more recently. Both of these things were unthinkable in 1993.) In some cases, gaming has reflected this progress. But too often, large segments of gaming culture have chosen to side instead with the reactionaries and the bigots, as Sierra implicitly did here.

So, Ken Williams and Sierra somehow managed to encompass both the best and the worst of what seems destined to go down in history as the defining art form of the 21st century, and they did so long before that century began. Yes, that’s quite an achievement in its own right — but, as Open Season so painfully reminds us, not an unmixed one.

(Sources: the books Blue: The LAPD and the Battle to Redeem American Policing by Joe Domanick and Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces by Radley Balko; Computer Gaming World of August/September 1987, October 1987, and December 1993; Sierra’s news magazines of Summer 1991, Winter 1992, June 1993, Summer 1993, Holiday 1993, and Spring 1994; Electronic Games of October 1993; Origin Systems’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of February 26 1993. Online sources include an excellent and invaluable Vice article on Open Season and the information about the Rodney King beating and subsequent trial found on Famous American Trials. And my thanks go out yet again to Corey Cole, who took the time to answer some questions about this period of Sierra’s history from his perspective as a developer there.

The four Police Quest adventure games are available for digital purchase at GOG.com.)

Alex Freeman

July 19, 2019 at 6:10 pm

Well, we definitely have racing simulations, both now and back then. We also have Phoenix Wright now.

As a side note, my dad evaded rioters on his way home from work during the Rodney King riots. However, he used my trick motorcyclists use to evade dogs. As the rioters headed toward him, he stopped. Then when they turned around, he zoomed off.

Sniffnoy

July 19, 2019 at 6:25 pm

Yeah Phoenix Wright cannot at all be called a laywer simulation…

(For those unfamiliar with Phoenix Wright… it’s basically like Perry Mason as an adventure game. Not, of course, to be confused with the one of those they actually made and which Jimmy has discussed here before. :) )

Alex Freeman

July 19, 2019 at 6:41 pm

Objection!

Sniffnoy

July 19, 2019 at 6:23 pm

Typospotting: You have “inequity” for “iniquity”.

Jimmy Maher

July 19, 2019 at 7:00 pm

Thanks!

Infinitron

July 19, 2019 at 6:35 pm

The cop killer was a Norman Bates ripoff, wasn’t he?

The game felt like it was in the same spirit as the television show “Cops” more than anything. It was dull to play but for a young gamer I can see parts of it being interesting. Where else was a white kid in 1993 going to get to talk to the grieving mother of a dead African-American boy whose body was found in a dumpster?

Andrew Pam

July 19, 2019 at 7:49 pm

“den of iniquity”, surely, rather than “inequity”? I thought California was known for its attempts at equity, rather than the reverse.

FightingBTQAbuse

July 19, 2019 at 8:38 pm

“All of which begs the question…” Jimmy, no :( I mean, far be it for me to promote linguistic prescriptivism, but sir, some lines should simply not be crossed, and standing by while people incorrectly use “begs the question” to stand in for “raises the question” is just more than a reasonable person should be asked to stand.

Jimmy Maher

July 20, 2019 at 4:48 am

It’s one of those linguistic oddities, like “disinterested” and “uninterested” that can mean two completely different — in this case even contradictory — things. I assume you prefer to see it used in its Aristotelian sense, where it refers to a foregone conclusion, but this is actually much less common in contemporary usage than the sense in which I used it. The latter has the advantage of aligning with the literal meanings of the words — never a bad thing in my book.

Andrew Plotkin

July 20, 2019 at 12:34 am

You referred to the “Iron-Contra scandal”, which brings any number of irresistable images to mind but is probably not what you meant.

(“Whose regime will reign supreme!?” Ok sorry.)

Jimmy Maher

July 20, 2019 at 4:50 am

:) Thanks!

John Parker

July 20, 2019 at 12:37 am

You have “Iron-Contra” rather than “Iran-Contra”. I always look forward to these articles BTW.

Lisa H.

July 20, 2019 at 1:47 am

The Patti Hearst saga

Patty (as you spelled it before). Maybe you had Passionate Patti in mind here? ;)

But then along came Rodney King of all people to take the inadvertent role of his bête noire.

I know it’s just an expression, but maybe one that doesn’t translate to “black beast” would be a better choice here…?

Jimmy Maher

July 20, 2019 at 5:07 am

Good catch. I never thought about the literal translation of the words. Thanks!

Dave W.

July 20, 2019 at 3:22 am

Note on the LA riot: Reginald Denny was pulled from his truck and beaten severely by the mob, but he survived the riot, although with serious injuries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Reginald_Denny

Jimmy Maher

July 20, 2019 at 5:07 am

Thanks!

Jason Dyer

July 20, 2019 at 4:27 am

The quote at the end about a racing simulation made me think “wait, didn’t Sierra publish a bunch of racing games?” and indeed they did, but they were developed by Papyrus, including the stellar Grand Prix Legends from 1998. (Which had terrible sales and probably deserves an essay of its own, but alas, we don’t have The Racing Game Addict yet.)

Jimmy Maher

July 20, 2019 at 5:10 am

I always found that game interesting as an attempt to do something really unique, simulating a single, very specific period in sporting history. But I’ve never actually played it, and I suspect it would be much too hardcore for my patience level.

So much more could be done with the concept. I can’t help but imagine a simulation of, say, the 1955 baseball season, drenched in period atmosphere. Maybe you could even license the book and call it The Boys of Summer.

Jason Dyer

July 20, 2019 at 2:56 pm

The 1995 game Oldtime Baseball comes close to what you mean. You can play in any season you want all the way back to 1871.

It’d be fun to pick a specific year and add narrative flavor! (Akin to Sean M. Shore’s Bonehead, from Spring Thing 2011. That game was great! … as long as you knew baseball.)

re: racing, there’s also Spirit of Speed 1937 for Dreamcast and PC, but that was shovelware. (I just checked Mobygames and the user review states “plays like a game from 1937”, heh.)

Alex Freeman

July 20, 2019 at 5:50 am

Oh, an interesting video with a cop completely unlike Gates:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hm9DAi1V5-E&list=PLwf_fKA2AmGrrU2nf6hQdlIpDSG4jP0pj&index=32&t=20s

John

July 20, 2019 at 11:09 pm

While Dragnet really is thinly-veiled propaganda for the LAPD and is problematic in a host of ways, I’m afraid you’ve mischaracterized it. Joe Friday, the protagonist, is indeed the “ideal cop”, but he’s a rule-follower, not a rule-breaker. He doesn’t need to excuse or justify his excesses because he never commits any, and Dragnet wants you to believe that the entire LAPD is always like that. Funnily enough, it sounds like Dragnet, with its emphasis on police procedure, has more in common with the pre-Gates Police Quests than it does with most other cop shows.

Jimmy Maher

July 21, 2019 at 10:41 am

A fair point. Thanks!

Michael

July 29, 2019 at 9:36 am

I’d say that the first 3 games, at least, have more to do with Dragnet’s *slightly* more liberal stepchild, Adam-12. When the story arch that carries you between all three entries is that the protagonist rekindles a romantic relationship with a prostitute, it can’t ALL be by the book.

That said, looking at the other comments here, PQ1 has always been among my top Sierra titles. Part of it is sentimental (it was my first Sierra title, copied from a newly made friend in the 6th grade) but also because, while there are some socially-questionable elements, they were a product of the time the game was made. Whereas Open Season, views had changed somewhat in the world since then, but the game didn’t adjust to their times.

Odkin

July 21, 2019 at 6:27 am

I lived in Los Angeles and since Gates quit it has descended to hell-hole status with useless, ineffective pansy policing. You’re pretty good on the video gae history, but your political injections are getting stale, partisan and increasingly disingenuous.

Alex Freeman

July 21, 2019 at 6:14 pm

Funny– Daryl Gates resigned in 1992. The crime rate in L.A. has gone down since then:

http://www.laalmanac.com/crime/cr02.php

Tom

July 22, 2019 at 1:06 pm

That may not prove as much as you want–crime in America in general has been dropping since the early ’90s.

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/03/5-facts-about-crime-in-the-u-s/

Ross

July 22, 2019 at 9:54 pm

I think it proves enough. “Cities are descending into uninhabitable hellholes of violent crime and we need tough cops who treat people of color like animals instead of pansies who respect the rights of minorities” is a pretty common misconception that correlates pretty closely with certain unfortunate cultural attitudes

Brian Bagnall

July 25, 2019 at 6:24 am

Has there been any consensus on why crime has been dropping since the 90s? I’ve always wondered if it had something to do with better video games and television. And of course that fascinating thing called the Internet. Did all this result in young men staying home rather than going out and causing trouble?

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2019 at 8:57 am

It’s a fascinating question that I’ve never seen comprehensively answered. One would think that the “tough on crime” contingent who have sent the United States’s prison populations soaring even as crime has fallen would be eager to take credit for the trend. But they’re caught in a rhetorical trap: their policies require them to sell a message of fear, and any hint of optimism undermines that message. Thus the war on crime and the war on drugs, like other wars on abstract nouns, are doomed always to fail — for to declare victory means to end them, something their advocates could never accept.

Facetious though it may sound, there is some merit to your second question. Even many researchers aren’t eager to talk about this — much less politicians! — but there’s a clear inverse correlation between access to pornography and rates of rape and sexual violence. It seems that pornography acts as a relief valve for sexually frustrated young men, keeping them from enacting their fantasies in real life by violent means. Notably, Middle Eastern countries, where pornography is still extremely hard to come by (sorry, couldn’t resist!), have far worse problems with sexual violence today than the Western secular democracies.

It is interesting to speculate whether the same principle might apply to violent videogames as well, but I’ve never really seen it addressed. Most studies are still focused on whether videogames make young men more violent, not less so.

But most of all, one certainly hopes that the declining rates of violence across the developed world are merely the continuation of a trend stretching back at least several centuries, over the course of which violence has become less and less acceptable a solution for problems in the eyes of average people. Steven Pinker published an exhaustive book on just that subject in 2011, called The Better Angles of Our Nature. A lot of his theses about root causes have been credibly challenged since, but it’s hard to argue with the impressive array of statistics he deploys to prove the bare fact of declining violence as a marked international trend.

Ross

July 25, 2019 at 2:03 pm

While there are certainly many factors, one that really sticks out is that it appears to correlate with environmental lead exposure. As in “We had several generations where young men in cities became disproportionately violent at age X. X years after we stopped putting lead in the gasoline, this stopped happening.” It’s known that brain damage from lead poisoning can affect the ability to control violent impulses, so it’s likely that even if it’s not THE cause, the removal of lead from gasoline and house paint played a role.

Brian Bagnall

July 25, 2019 at 2:59 pm

There’s a Wikipedia article on the worldwide crime drop in the early 1990s (50 to 75% in some cases). It lists 7 possible causes, but none of them include the rise of the Internet or video games: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crime_drop

Maybe “economic factors” could theoretically include these two technologies but they sure don’t state it. It clearly says the drop started in 1994, which coincides with two big things that affected teens/young men: Doom and Netscape Navigator.

The article on US Crime shows that there was a decline in crime since the colonial days that reversed in the 1960s. It lists 11 possible causes for the drop in crime, focusing on institutional causes and omitting new technology:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crime_in_the_United_States#Crime_over_time

I think they are missing the boat on the effects of the Internet and video games, but I guess I can’t really prove it other than a gut feeling based on what me and other young people were distracted by at the time.

A Google search for “drop in crime internet video games” shows lots of people speculating that was the cause.

GeoX

July 25, 2019 at 1:58 am

I thought: is there going to be a pro-police-brutality comment? Then I scrolled down and whaddaya know? Congratulations, I guess.

Peter Orvetti

July 25, 2019 at 7:04 am

And he made the 405 run on time…

Tim

October 19, 2020 at 12:45 am

It really does taint otherwise excellent retrospectives. I don’t recall if I’ve made this analogy before, but it’s like having a world class pastry chef, who also *loves* mustard and insists on occasionally dousing his creations with the stuff.

Martin

July 21, 2019 at 6:56 am

I’m assuming this is a single article story so I’ll these things now. So you say the game was no good which is OK as a summary but, assuming there were puzzles, were they fair? Was the game mechanics good/bad/indifferent? If someone knew nothing about the Rodney King affair (such as younger people now or people outside the US), how would it play for them? … Those sort of questions.

If this is just part One, just ignore this.

Jimmy Maher

July 21, 2019 at 8:09 am

Carl Muckenhoupt on Twitter described playing this game as “like looking at Hitler’s paintings.” Not sure I’d go that far, but I found it very unpleasant. I judge a summary to be all that is needed here. This game’s importance doesn’t lie in the delight it brought its players. Best to save the in-depth reviews for games that were created in better faith.

Ross

July 24, 2019 at 12:35 am

it’s also true that LucasArts had nothing like the ambition for adventure games which Ken Williams expresses here

That pretty much sums up why I always favored Sierra and wasn’t nearly as interested in LucasArts. Sierra games were so frequently big glorious messes, but they were always trying new, ambitious things and did not let the fact that the games kept ending up ridiculous messes deter them

Max Noel

July 24, 2019 at 2:43 pm

Side note: Mobygames calls Police Quest 5: SWAT a “tactical simulation”. It’s true that the series would eventually become that (first-person tactical shooters in the vein of the original Rainbow Six), starting with SWAT 3, when it dropped both Daryl Gates and the Police Quest prefix.

But prior to that, PQ: SWAT is the kind of game you’ll probably want to cover at some point. It is, indeed, an adventure game (clearly built on the tech from Open Season). And not just any adventure game. It’s a member of that most reviled class of mid-1990s adventure games: the interactive movie. Despite exactly one good idea (midway through the game you can become either a sniper or a SWAT team leader, which hard branches the story, adding some replayability), it’s a textbook example of all the weaknesses of the form and none of its strengths.

Given that this was my first Sierra adventure game (one which immediately sent me running back to LucasArts), I’d be very interested in reading your take on it.

(As for SWAT 2, Wikipedia tells me it was an RTS. Which, I guess, in 1998, every game had to be.)

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2019 at 7:57 am

I have difficulty calling it an adventure game. A hybrid at best, mixing elements of a lot of different genres to not-very-satisfying effect, hobbled as it is by all the usual constraints that come with full-motion video. I’m afraid I don’t feel a huge need to cover it any further. I feel like I’ll spend more than enough time to discussing the (few) advantages and (many) disadvantages of FMV in the context of games that are either more intrinsically interesting or at least more historically important.

Peter

July 24, 2019 at 8:41 pm

This is a great piece.

Also, the earlier Police Quest games are super-reactionary too, albeit in a way that feels more hilarious than actually offensive. The critic Line Hollis has recaps of the first two here:

http://www.linehollis.com/tag/line-on-sierra/

Peter Orvetti

July 25, 2019 at 7:17 am

Wow, that was a great read. I remembered only two things about “Police Quest”:

— The poker game

— Running a red or yellow light resulted in death for some reason

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2019 at 8:04 am

Yeah, but the earlier games manifest a sort of passive racism, born more from complacency, a lack of empathy, and an unwillingness to look beyond the convenient, easy answers than outright bad intent. Open Season, on the other hand, has bad intent to burn. (On the third hand, the former stripe of racism is more symptomatic of Western culture today, and thus more pernicious and problematic. We have more Jim Wallses than we do Daryl Gateses.)

Peter Malamud Smith

July 25, 2019 at 2:12 pm

That’s well put, yeah. The less virulent kind is probably more dangerous, because it sneaks under the radar.

Hagay

July 24, 2019 at 9:34 pm

That was a fascinating read. I played the game several times over the years and always got a strangely bleak, uncomfortable vibe from it even without knowing any of the context (I live in Israel and didn’t know much about Rodney King and the riots until now). The previous games in the series were pedantic but at least they had actual characters and a plot that made a tiny bit of sense.

Peter Malamud Smith

July 25, 2019 at 3:04 am

Also—I think Ken was somewhat conservative himself, at least by this point, because I remember a mention of his Rush Limbaugh fandom in an issue of the Sierra magazine. In fact—yikes, I may be misremembering this, but I think that mention was in a puff piece about how he and Gates hit it off…

Jimmy Maher

July 25, 2019 at 8:10 am

Yes, as Ken Williams’s income increased, his politics shifted rightward — by no means an atypical progression. By 1993, Rush Limbaugh was popping up in his columns with some regularity. There was a lot of talk among the rank and file at Sierra that one of his biggest motivations for moving the company’s headquarters to Seattle in late 1993 was the fact that Washington had no state income tax; California, on the other hand, had the highest in the nation. So much for the hippie dream of getting back to the land…

Nothanks

July 26, 2019 at 7:13 am

Way too judgmental compared to your usual work, you come off like such an obnoxious underwear-sniffer salivating about Sierra.

Milk

July 30, 2019 at 12:11 pm

thank you. Felt the same way. The piece tries to pretend some sort of level headedness bur can’t help but let a somewhat emotional attachment to the subject with it’s fair share of pearl clutching moments, imcluding tge classic blanket terms “racist” and “biggot” to simplify any complex social political matter, ironically while crying for nuance and empathy. He did try to provide a hint of a possible oposing view, but it barely cracked through the surface. His view of conservative america seems to be as steriotipical or “problematic” as he makes his cartoon caricatures of 90’s cop view of race to be.

Carlton Little

July 30, 2019 at 7:05 pm

Is it just me, or does this comment read as *suspiciously* supportive of a clearly intentional dig?

UGHHHHHHHHH

July 26, 2019 at 7:18 am

Pretty cute to see you babbling about “kindness and respect” while shitting all over Ken Williams, one of the people who make your entire existence possible. Shame on you.

Jimmy Maher

July 26, 2019 at 7:26 am

You’re totally welcome to state your point of view, my friend, but I need you to choose one name to state it under. (I can see your MAC address, you know.) From now on, you’ll have to be known as either Nothanks or UGHHHHHHHHH. (That’s with 9 H’s.)

Snow

July 28, 2019 at 9:23 pm

“I can see your MAC address, you know.”

This shouldn’t be possible.

https://superuser.com/a/114112

Jimmy Maher

July 29, 2019 at 4:44 am

Okay, IP address and MAC address of border router. ;)

Snow

July 29, 2019 at 9:46 am

I think this is actually a serious topic.

The only MAC address you (as the website’s host) should be able to see is the MAC address of your own border router at the ISP for your server. This MAC address would be the same for all users (within a time period) and couldn’t be used for identification of users.

If you are able to identify users due to MAC addresses from users your site collects when they post comments, then I find this concerning. That would be contrary to your (Akismet’s) privacy policy that says “we collect information that web browsers, mobile devices, and servers typically make available, such as the browser type, IP address, unique device identifiers”. “Unique device identifiers” might refer to MAC addresses, but they’re not “typically made available” as far as I know.

If you were mistaken about being able to identify users according to the MAC addresses in your logs, or if you were joking, then please consider explicitly stating that you can’t actually identify users this way. If I’m mistaken, I would like to ask for a more thorough explanation about which pieces of information you are collecting.

Why am I this strident about this? Because letting this statement stand if it’s wrong would mean that it is actually spreading FUD. Users might refrain from posting (on other sites too!) if they think that their posts can be correlated to them even when using different user names and mail addresses, and when posting with different IP addresses. Regrettably, there are other means of fingerprinting users, but I would hope that you don’t employ them.

Jimmy Maher

July 29, 2019 at 10:07 am

I do absolutely no tracking beyond what’s to be found in a vanilla WordPress installation, and have no interest in doing so.

Looking at this yet a third time, what I see from the user in question is a string of 8 four-digit hexadecimal numbers separated by colons. I jumped to the conclusion that this was his MAC address. Now, I realize it must be his IPv6 address. For you and most other commenters, I simply see an IP address in the form I’m used to.

I apologize for the misinformation. When I wrote the first comment, I was irritated with having to clear away a bunch of comments from what was obviously the same user with a whole pile of strawmen. When I replied to you the first time, I was busy working through my morning emails and dealing with what I thought to be — *thought* to be — more pressing matters, and so just took a quick look at the link you provided and jumped to conclusions. As should be abundantly obvious by now, I’m not an expert on any of these subjects, nor are they a big interest of mine. While I do have the IT background to learn about them when I absolutely need to, I tend to deal with such things only to the extent I need to to keep my site operating and safe — most of all for my commenters, whom I value more than I can say. But a lack of expertise should cause me to be less flippant, not more so. The only thing I can say in my defense is that my misinformation was a product of complete naivete about this sort of thing rather than guile.

Snow

July 29, 2019 at 12:01 pm

Thank you for the clarification!

SYH

July 26, 2019 at 4:53 pm

SWAT is responsible for maybe the strangest lineage of games I can think of- you can draw a line from Police Quest (and even Kings Quest if you’re feeling adventurous) all the way through a lot of bad games to SWAT 4, still considered one of the greatest tactical combat games ever made. How many long running series peak with their final entry and then end?

Peter Orvetti

July 29, 2019 at 10:23 pm

I’m a bit surprised some readers think you’ve been too hard on the Williamses. I think your pieces on them have been fair explorations of two complex people.

I came across this blog while googling something Infocommy, and have read pretty much every post. I remember many of these games from my youth, but knew little of the history. I’m not much of a “gamer”, but the history of the early industry fascinates me. I knew very little about Sierra.

Ken Williams seems to have been a man torn between the cultural and political trends of his era and his own ambition and drive for success. (I feel like he cared more about winning than about getting rich.) As for Roberta Williams, while you are pretty critical of her output, I sense a real respect for what she achieved in a male-dominated (and outright sexist) industry.

Alex Freeman

August 1, 2019 at 4:17 pm

Funny you should say that. From this interview:

http://web.archive.org/web/20070311121225/http://www.womengamers.com/interviews/roberta.php

Zack

July 31, 2019 at 7:33 am

Thank you for the article !

I’m really curious to know how Sierra, adventure-games powerhouse, ended up doing Caesar, Olympus, Emperor, Pharaoh. Not sure if you wrote about it already, the site is so dense I barely read a lot of it even after a year.

Swizzle

August 1, 2019 at 10:12 pm

I’m clearly in the minority on this blog who is very disappointed with this article. I don’t care to re-read it to pull out each specific part for discussion. I came here to read about video games, not your personal views of law enforcement.

Sebastian

July 11, 2020 at 5:58 am

Jimmy has added his personal opinion on the background of every game with an unusual topic afaict. Why should this one be different?

TIm

October 19, 2020 at 12:49 am

Doesn’t make it any less obnoxious.

Jason

August 2, 2019 at 9:44 pm

I was always curious about the real story behind Jim Walls leaving Sierra. Is it really that simple — Tsunami offered him a better deal?

I played Blue Force. It was not very good. Catchy theme tune, though. I also thought that PQ3 wasn’t particularly great — but it was miles better than Open Season, which I never even finished.

PQ1 and PQ2, though? Those were mighty exciting games for a very young me. I was about 7 when PQ1 came out.

Jimmy Maher

August 3, 2019 at 8:05 am

Yes, I think it pretty much was that simple. He certainly wasn’t the only one to go; Edmond Heinbockel made a pitch to most of Sierra’s technical and creative staff, and a number of others took him up on it. Walls was just the only really high-profile name among them that fans might immediately recognize. Ken Williams was truly livid at all of them, but particularly at Walls; he felt he was owed a lot more loyalty than he got, given the way he’d plucked Walls out of his PTSD depression (as he saw it, anyway) and made him into a game designer.

In the long run, Tsunami wasn’t a good career move for Walls or anyone else. They quickly gained the reputation of a company more interested in sensationalism and hype than actually buckling down to make good games. And they were ethically challenged to boot. They got themselves pretty much blacklisted from Computer Gaming World magazine when they extracted a bunch of out-of-context quotes from a lukewarm review (of Ringworld, I think), and splashed them all over their advertising as if the review had declared the game the best one ever made. It was decidedly not smart to get on the bad side of the biggest, most respected magazine in the industry. After Tsunami, Walls managed to get a job with Westwood, but he never got a chance again to design a game that was solely his own.

Jason Artman

August 2, 2019 at 9:46 pm

Forgot to mention this. Jim Walls attempted to get back into game design with a game called Precinct in 2013. The game was quietly cancelled when it became obvious that it wasn’t going to meet its Kickstarter goal.

https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2013/08/27/cop-out-precinct-crowd-funding-cancelled/

Colin Djukic

August 4, 2019 at 7:22 pm

Hi I just wanted to say that I, as

always, loved to read the article, and that I do want to read about your opinion on police brutality or whatever comes to your mind, thanks;-)

stephane

August 6, 2019 at 8:58 pm

Wow, amazing read. Police quest from Sierra and many other titles from Sierra brings me back to my youth. Best days of my life. But I didn’t know about Daryl Gates nor I even searched or thought about searching for him. With that blog of yours about this, if theres one thing that Police Quest needs is a reboot. A complete fresh overall or new fresh look. With Daryl Gates and the death of Police Quest and Sierra, I think this game deserves it the most. At least a last good game thats names Police Quest or similar.

I mean technologically its possible to do and Activate has the resrrouces which Sierra barely had compared to Activision anyways.An adventure game with procedurally generated algorithm used as content like missions as a cop would be easily feasible today. Anyways, thats my take on it. thanks for the read

typolice

August 7, 2019 at 4:37 am

Minor nitpick from a minor patron: “he had starting asking”

Jimmy Maher

August 7, 2019 at 4:46 am

Thanks!

Leo Vellés

June 19, 2020 at 4:49 pm

Wow, reading today Vice’s article’s last paragraph after the recent murder of Floyd George is chilling. Seems nothing changed in how police operates. So sad

Fronzel

February 20, 2021 at 5:36 am