Around twenty years ago, people would have laughed if you told them that videogames would end up at the Smithsonian, but the Half-Life team really did want to make games that were more than just throwaway toys. The rule against cinematics — which made our jobs much harder and also ended up leaving a lot of my favorite work out of the game — was a kind of ideological stake in the ground: we really did want the game and the story to be the same thing. It was far from flawless, but it was really trying to push the boundaries of a young medium.

— Valve artist Steve Theodore

By 1998, the first-person shooter was nearing its pinnacle of popularity. In June of that year, Computer Gaming World magazine could list fourteen reasonably big-budget, high-profile FPS’s earmarked for release in the next six months alone. And yet the FPS seemed rather to be running to stand still. Almost all of the innovation taking place in the space was in the realm of technology rather than design.

To be sure, progress in the former realm was continuing apace. Less than five years after id Software had shaken the world with DOOM, that game’s low-resolution 2.5D graphics and equally crude soundscapes had become positively quaint. Aided and abetted by a fast-evolving ecosystem of 3D-graphics hardware from companies like 3Dfx, id’s Quake engine had raised the bar enormously in 1996; ditto Quake II in 1997. These were the cutting-edge engines that everyone with hopes of selling a lot of shooters scrambled to license. Then, in May of 1998, with Quake III not scheduled for release until late the following year, Epic MegaGames came along with their own Unreal engine, boasting a considerably longer bullet list of graphical effects than Quake II. In thus directly challenging id’s heretofore unquestioned supremacy in the space, Unreal ignited a 3D-graphics arms race that seemed to promise even faster progress in the immediate future.

Yet whether they sported the name Quake or Unreal or something else on their boxes, single-player FPS’s were still content to hew to the “shooting gallery” design template laid out by DOOM. You were expected to march through a ladder-style campaign consisting of a set number of discrete levels, each successive one full of more and more deadly enemies to kill than the last, perhaps with some puzzles of the lock-and-key or button-mashing stripe to add a modicum of variety. These levels were joined together by some thread of story, sometimes more elaborate and sometimes — usually — less so, but so irrelevant to what occurred inside the levels that impatient gamers could and sometimes did skip right over the intervening cutscenes or other forms of exposition in order to get right back into the action.

This was clearly a model with which countless gamers were completely comfortable, one which had the virtue of allowing them maximal freedom of choice: follow along with the story or ignore it, as you liked. Or, as id’s star programmer John Carmack famously said: “Story in a game is like a story in a porn movie. It’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.”

But what if you could build the story right into the gameplay, such that the two became inseparable? What if you could eliminate the artificial division between exposition and action, and with it the whole conceit of a game as a mere series of levels waiting to be beaten one by one? What if you could drop players into an open-ended space where the story was taking place all around them?

This was the thinking that animated an upstart newcomer to the games industry that went by the name of Valve L.L.C. The game that resulted from it would prove the most dramatic conceptual advance in the FPS genre since DOOM, with lessons and repercussions that reached well beyond the borders of shooter country.

The formation of Valve was one of several outcomes of a dawning realization inside the Microsoft of the mid-1990s that computer gaming was becoming a very big business. The same realization led a highly respected Microsoft programmer named Michael Abrash to quit his cushy job in Redmond, Washington, throw his tie into the nearest trashcan, and move to Mesquite, Texas, to help John Carmack and the other scruffy id boys make Quake. It led another insider named Alex St. John to put together the internal team who made DirectX, a library of code that allowed game developers and players to finally say farewell to creaky old MS-DOS and join the rest of the world that was running Windows 95. It led Microsoft to buy an outfit called Ensemble Studios and their promising real-time-strategy game Age of Empires as a first wedge for levering their way into the gaming market as a publisher of major note. And it led to Valve Corporation.

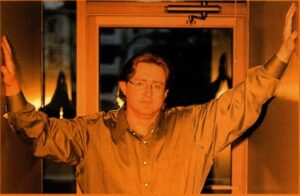

In 1996, Valve’s future co-founders Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington were both valued employees of Microsoft. Newell had been working there in project-management roles since 1983; he had played an important part in the creation of the early versions of Windows before moving on to Microsoft Office and other high-profile applications. Harrington was a programmer whose tenure had been shorter, but he had made significant contributions to Windows NT, Microsoft’s business- and server-oriented operating system.

As Newell tells the tale, he had an epiphany when he was asked to commission a study to find out just how many computers were currently running Microsoft Windows in the United States. The number of 20 million that he got back was impressive. Yet he was shocked to learn that Windows wasn’t the most popular single piece of software to be found on American personal computers; that was rather a game called DOOM. Newell and Harrington had long enjoyed playing games. Now, it seemed, there were huge piles of money to be earned from making them. Doing so struck them as a heck of a lot more fun than making more operating systems and business software. It was worth a shot, at any rate; both men were wealthy enough by now that they could afford to take a flier on something completely different.

So, on August, 24, 1996, the pair quit Microsoft to open an office for their new company Valve some five miles away in Kirkland, Washington. At the time, no one could have imagined — least of all them — what a milestone moment this would go down as in the history of gaming. “On the surface, we should have failed,” says Gabe Newell. “Realistically, both Mike and I thought we would get about a year into it, realize we’d made horrible mistakes, and go back to our friends at Microsoft and ask for our jobs back.”

Be that as it may, they did know what kind of game they wanted to make. Or rather Newell did; from the beginning, he was the driving creative and conceptual force, while Harrington focused more on the practical logistics of running a business and making quality software. Like so many others in the industry he was entering, Newell wanted to make a shooter. Yet he wanted his shooter to be more immersive and encompassing of its player than any of the ones that were currently out there, with a story that was embedded right into the gameplay rather than standing apart from it. Valve wasted no time in licensing id’s Quake engine to bring these aspirations to life, via the game that would come to be known as Half-Life.

As the id deal demonstrates, Newell and Harrington had connections and financial resources to hand that almost any other would-be game maker would have killed for; both had exited Microsoft as millionaires several times over. Yet they had no access to gaming distribution channels, meaning that they had to beat the bush for a publisher just like anyone else with a new studio. They soon found that their studio and their ambitious ideas were a harder sell than they had expected. With games becoming a bigger business every year, there were a lot of deep-pocketed folks from other fields jumping into the industry with plans to teach all of the people who were already there what they were doing wrong; such folks generally had no clue about what it took to do games right. Seasoned industry insiders had a name for these people, one that was usually thoroughly apt: “Tourists.” At first glance, the label was easy to apply to Newell and Harrington and Valve. Among those who did so was Mitch Lasky, then an executive at Activision, who would go on to become a legendary gaming venture capitalist. He got “a whiff of tourism” from Valve, he admits. He says he still has “post-traumatic stress disorder” over his decision to pass on signing them to a publishing deal — but by no means was he the only one to do so.

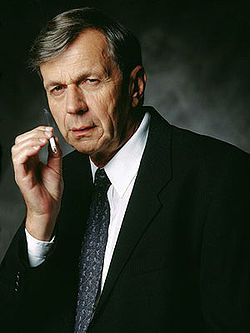

Newell and Harrington finally wound up pitching to Sierra, a publisher known primarily for point-and-click adventure games, a venerable genre that was now being sorely tested by all of the new FPS’s. In light of this, Sierra was understandably eager to find a horse of the new breed to back. The inking of a publishing deal with Valve was one of the last major decisions made by Ken Williams, who had founded Sierra in his living room back in 1980 but had recently sold the business he had built from the ground up. He wasn’t getting along very well with the buyers, and was already eying the exit. But for now, he was still taking meetings like this one.

As a man with such deep roots in adventure games, Williams found Valve’s focus on story both refreshing and appealing. Still, there was a lot of wrangling between the parties, mainly over the ultimate disposition of the rights to the Half-Life name; Williams wanted them to go to Sierra, but Newell and Harrington wanted to retain them for themselves. In the end, with no other publishers stepping up to the plate, Valve had to accept what Sierra was offering, a capitulation that would lead to a lengthy legal battle a few years down the road. For now, though, they had their publisher.

As for Ken Williams, who would exit the industry stage left well before Half-Life was finished:

Now that I’m retired, people sometimes ask me what I used to do. I usually just say, “I had a game company back in the old days.” That inevitably causes them to say, “Did you make any games I might have heard of?” I answer, “Leisure Suit Larry.” That normally is sufficient, but if there is no glimmer of recognition I pull out the heavy artillery and say, “Half-Life.” Unless they’ve been sleeping under a rock for the last couple of decades, that always lights up their eyes.

One can imagine worse codas to a business career…

In what could all too easily be read as another sign of naïve tourism, Newell and Harrington agreed to a crazily optimistic development timeline, promising a finished game for the Christmas of 1997, which was just one year away. To make it happen, they hired a few dozen level designers, programmers, artists, and other creative and technical types, many of whom had no prior professional experience in the games industry, all of whom recognized what an extraordinary opportunity they were being handed and were willing to work like dogs to make the most of it. The founders tapped a fertile pool of recruits in the online DOOM and Quake modding scenes, where amateurs were making names for themselves by bending those engines in all sorts of new directions. They would now do the same on a professional basis at Valve, even as the programmers modified the Quake engine itself to suit their needs, implementing better lighting and particle effects, and adding scripting and artificial-intelligence capabilities that the straightforward run-and-shoot gameplay in which id specialized had never demanded. Gabe Newell would estimate when all was said and done that 75 percent of the code in the engine had been written or rewritten at Valve.

In June of 1997, Valve took Half-Life to the big E3 trade show, where it competed for attention with a murderers’ row of other FPS’s, including early builds of Unreal, SiN, Daikatana, Quake II, and Jedi Knight. Valve didn’t even have a booth of their own at the show. Nor were they to be found inside Sierra’s; Half-Life was instead shown in the booth of 3Dfx. Like so many of Valve’s early moves, this one was deceptively clever, because 3Dfx was absolutely huge at the time, with as big a buzz around their hardware as id enjoyed around their software. Half-Life walked away from the show with the title of “Best Action Game.”

The validation of E3 made the unavoidable moment of reckoning that came soon after easier to stomach. I speak, of course, about the moment when Valve had to recognize that they didn’t have a ghost of a chance of finishing the game that they wanted to make within the next few months. Newell and Harrington looked at the state of the project and decided that they could probably scrape together a more or less acceptable but formulaic shooter in time for that coming Christmas. Or they could keep working and end up with something amazing for the next Christmas. To their eternal credit, they chose the latter course, a decision which was made possible only by their deep pockets. For Sierra, who were notorious for releasing half-finished games, certainly did not intend to pay for an extra year of development time. The co-founders would have to foot that bill themselves. Nevertheless, to hear Gabe Newell tell it today, it was a no-brainer: “Late is just for a little while. Suck is forever.”

The anticipation around Half-Life didn’t diminish in the months that followed, not even after the finished Unreal took the world by storm in May of 1998. Despite being based on a two-plus-year-old engine in a milieu that usually prized the technologically new and shiny above all else, Valve’s “shooter with a story” had well and truly captured the imaginations of gamers. During the summer of 1998, a demo of the game consisting of the first three chapters — including the now-iconic opening scenes, in which you ride a tram into a secret government research facility as just another scientist on the staff headed for another day on the job — leaked out of the offices of a magazine to which it had been sent. It did more to promote the game than a million dollars worth of advertising could have; the demo spread like wildfire online, raising the excitement level to an even more feverish pitch. Half-Life was different enough to have the frisson of novelty in the otherwise homogeneous culture of the FPS, whilst still being readily identifiable as an FPS. It was the perfect mix of innovation and familiarity.

So, it was no real surprise when the full game turned into a massive hit for Valve and Sierra after its release on November 19, 1998. The magazines fell all over themselves to praise it. Computer Gaming World, normally the closest thing the hype-driven journalism of gaming had to a voice of sobriety, got as high on Half-Life’s supply as anyone. The magazine’s long-serving associate editor Jeff Green took it upon himself to render the official verdict.

Everything you’ve heard, everything you’ve hoped for — it’s all true. Half-Life, Valve Software’s highly anticipated first-person shooter, is not just one of the best games of the year. It’s one of the best games of any year, an instant classic that is miles better than any of its immediate competition, and, in its single-player form, is the best shooter since DOOM. Plus, despite the fact that it’s “just” a shooter, Half-Life provides one of the best examples ever of how to present an interactive movie — and a great, scary movie at that.

Half-Life sold its first 200,000 copies in the United States before Christmas — i.e., before glowing reviews like the one above even hit the newsstands. But this was the barest beginning to its success story. In honor of its tenth birthday in 2008, Guinness of world-records fame would formally anoint Half-Life as the best-selling single FPS in history, with total sales in the neighborhood of 10 million copies across all platforms and countries. For Newell and Harrington, it was one hell of a way to launch a game-development studio. For Sierra, who in truth had done very little for Half-Life beyond putting it in a box and shipping it out to stores, it was a tsunami of cash that seemed to come out of nowhere, the biggest game they had ever published almost by an order of magnitude. One does hope that somebody in the company’s new management took a moment to thank Ken Williams for this manna from heaven.

Half-Life has come to occupy such a hallowed, well-nigh sacrosanct position in the annals of gaming that any encounter with the actual artifact today seems bound to be slightly underwhelming. Yet even when we take into account the trouble that any game would have living up to a reputation as elevated as this one’s, the truth is that there’s quite a lot here for the modern skeptical critic to find fault with — and, Lord knows, this particular critic has seldom been accused of lacking in skepticism.

Judged purely as a shooter, the design shows its age. It’s sometimes amazingly inspired, but more often no better than average for its time. There’s a lot of crawling through anonymous vents that serve no real purpose other than to extend the length of the game, a lot of places where you can survive only by dying first so as to learn what’s coming, a lot of spots where it’s really not clear at all what the game wants from you. And then there are an awful lot of jumping puzzles, shoehorned into a game engine that has way more slop in it than is ideal for such things. I must say that I had more unadulterated fun with LucasArts’s Jedi Knight, the last shooter I played all the way through for these histories, than I did with Half-Life. There the levels are constructed like thrill rides straight out of the Star Wars films, with a through-line that seems to just intuitively come to you; looking back, I’m still in awe of their subtle genius in this respect. Half-Life is not like that. You really have to work to get through it, and that’s not as appealing to me.

Then again, my judgment on these things should, like that of any critic, be taken with a grain of salt. Whether you judge a game good or bad or mediocre hinges to a large degree on what precisely you’re looking for from it; we’ve all read countless negative reviews reflective not so much of a bad game as one that isn’t the game that that reviewer wanted to play. Personally, I’m very much a tourist in the land of the FPS. While I understand the appeal of the genre, I don’t want to expend too many hours or too much effort on it. I want to blast through a fun and engaging environment without too much friction. Make me feel like an awesome action hero while I’m at it, and I’ll probably walk away satisfied, ready to go play something else. Jedi Knight on easy mode gave me that experience; Half-Life did not, demanding a degree of careful attention from me that I wasn’t always eager to grant it. If you’re more hardcore about this genre than I am, your judgment of the positives and negatives in these things may very well be the opposite of mine. Certainly Half-Life is more typical of its era than Jedi Knight — an era when games like this were still accepted and even expected to be harder and more time-consuming than they are today. C’est la vie et vive la différence!

But of course, it wasn’t the granular tactical details of the design that made Half-Life stand out so much from the competition back in the day. It was rather its brilliance as a storytelling vehicle that led to its legendary reputation. And don’t worry, you definitely won’t see me quibbling that said reputation isn’t deserved. Even here, though, we do need to be sure that we understand exactly what it did and did not do that was so innovative at the time.

Contrary to its popular rep then and now, Half-Life was by no means the first “shooter with a story.” Technically speaking, even DOOM has a story, some prattle about a space station and a portal to Hell and a space marine who’s the only one that can stop the demon spawn. The story most certainly isn’t War and Peace, but it’s there.

Half-Life wasn’t even the shooter at the time of its release with the inarguably best or most complicated story. LucasArts makes a strong bid for the title there. Both Dark Forces and the aforementioned Jedi Knight, released in 1995 and 1997 respectively, weave fairly elaborate tales into the fabric of the existing Star Wars universe, drawing on its rich lore, inserting themselves into the established chronology of the original trilogy of films and the “Expanded Universe” series of Star Wars novels.

Like that of many games of this era, Half-Life’s story betrays the heavy influence of the television show The X-Files, which enjoyed its biggest season ever just before this game was released. We have the standard nefarious government conspiracy involving extraterrestrials, set in the standard top-secret military installation somewhere in the Desert Southwest. We even have a direct equivalent to Cancer Man, The X-Files’s shadowy, nameless villain who is constantly lurking behind the scenes. “G-Man” does the same in Half-Life; voice actor Michael Shapiro even opted to give him a “lizard voice” that’s almost a dead ringer for Cancer Man’s nicotine-addled croak.

All told, Half-Life’s story is more of a collection of tropes than a serious exercise in fictional world-building. To be clear, the sketchiness is by no means an automatically bad thing, not when it’s judged in the light of the purpose the story actually needs to serve. Mark Laidlaw, the sometime science-fiction novelist who wrote the script, makes no bones about the limits to his ambitions for it. “You don’t have to write the whole story,” he says. “Because it’s a conspiracy plot, everybody knows more about it than you do. So you don’t have to answer those questions. Just keep raising questions.”

Once the shooting starts, plot-related things happen, but it’s all heat-of-the-moment stuff. You fight your way out of the complex after its been overrun by alien invaders coming through a trans-dimensional gate that’s been inadvertently opened, only to find that your own government is now as bent on killing you as the aliens are in the name of the disposal of evidence. Eventually, in a plot point weirdly reminiscent of DOOM, you have to teleport yourself onto the aliens’ world to shut down the portal they’re using to reach yours.

Suffice to say that, while Half-Life may be slightly further along the continuum toward War and Peace than DOOM is, it’s only slightly so. Countless better, richer, deeper stories were told in games before this one came along. When people talk about Half-Life as “the FPS with a story,” they’re really talking about something more subtle: about its way of presenting its story. Far from diminishing the game, this makes it more important, across genres well beyond the FPS. The best way for us to start to come to grips with what Half-Life did that was so extraordinary might be to look back to the way games were deploying their stories before its arrival on the scene.

Throughout the 1980s, story in games was largely confined to the axiomatically narrative-heavy genres of the adventure game and the CRPG. Then, in 1990, Origin Systems released Chris Roberts’s Wing Commander, a game which was as revolutionary in the context of its own time as Half-Life was in its. In terms of gameplay, Wing Commander was a “simulation” of outer-space dog-fighting, not all that far removed in spirit from the classic Elite. What made it stand out was what happened when you weren’t behind the controls of your space fighter. Between missions, you hung out in the officers’ lounge aboard your mother ship, collecting scuttlebutt from the bartender, even flirting with the fetching female pilot in your squadron. When you went into the briefing room to learn about your next mission, you also learned about the effect your last one had had on the unfolding war against the deadly alien Kilrathi, and were given a broader picture of the latest developments in the conflict that necessitated this latest flight into danger. The missions themselves remained shooting galleries, but the story that was woven around them gave them resonance, made you feel like you were a part of something much grander. Almost equally importantly, this “campaign” provided an easy way to structure your time in the game and chart your improving skills; beat all of the missions in the campaign and see the story to its end, and you could say that you had mastered the game as a whole.

People loved this; Wing Commander became by far the most popular computer-gaming franchise of the young decade prior to the smashing arrival of DOOM at the end of 1993. The approach it pioneered quickly spread across virtually all gaming genres. In particular, both the first-person-shooter and the real-time strategy genres — the two that would dominate over all others in the second half of the decade — adopted it as their model for the single-player experience. Even at its most rudimentary, a ladder-style campaign gave you a goal to pursue and a framework of progression to hang your hat on.

Yet the same approach created a weirdly rigid division between gameplay and exposition, not only on the playing side of the ledger but to a large extent on the development side as well. It wasn’t unusual for completely separate teams to be charged with making the gameplay part of a game and all of the narrative pomp and circumstance that justified it. The disconnect could sometimes verge on hilarious; in Jedi Knight, which went so far as to film real humans acting out a B-grade Star Wars movie between its levels, the protagonist has a beard in the cutscenes but is clean-shaven during the levels. By the late 1990s, the pre-rendered-3D or filmed-live-action cutscenes sometimes cost more to produce than the game itself, and almost always filled more of the space on the CD.

As he was setting up his team at Valve, Gabe Newell attempted to eliminate this weird bifurcation between narrative and gameplay by passing down two edicts to his employees, the only non-negotiable rules he would ever impose upon them. Half-Life had to have a story — not necessarily one worthy of a film or a novel, but one worthy of the name. And at the same time, it couldn’t ever, under any conditions, from the very first moment to the very last, take control out of the hands of the player. Everything that followed cascaded from these two simple rules, which many a game maker of the time would surely have seen as mutually contradictory. To state the two most obvious and celebrated results, they meant no cutscenes whatsoever and no externally imposed ladder of levels to progress through — for any sort of level break did mean taking control out of the hands of the player, no matter how briefly.

Adapting to such a paradigm the Quake engine, which had been designed with a traditional FPS campaign in mind, proved taxing but achievable. Valve set up the world of Half-Life as a spatial grid of “levels” that were now better described as zones; pass over a boundary from one zone into another, and the new one would be loaded in swiftly and almost transparently. Valve kept the discrete zones small so as to minimize the loading times, judging more but shorter loading breaks to be better than fewer but longer ones. The hardest part was dealing with the borderlands, so to speak; you needed to be able to look into one zone from another, and the enemies and allies around you had to stay consistent before and after a transition. But Valve managed even this through some clever technical sleight of hand — such as by creating overlapping areas that existed in both of the adjoining sets of level data — and through more of the same on the design side, such as by placing the borders whenever possible at corners in corridors and at other spots where the line of sight didn’t extend too far. The occasional brief loading message aside — and they’re very brief, or even effectively nonexistent, on modern hardware — Half-Life really does feel like it all takes place in the same contiguous space.

Every detail of Half-Life has been analyzed at extensive, exhaustive length over the decades since its release. Such analysis has its place in fan culture, but it can be more confusing than clarifying when it comes to appreciating the game’s most important achievements. The ironic fact is that you can learn almost everything that really matters about Half-Life as a game design just by playing it for an hour or so, enough to get into its third chapter. Shall we do so together now?

Half-Life hews to Gabe Newell’s guiding rules from the moment you click the “New Game” button on the main menu and the iconic tram ride into the Black Mesa Research Center begins. The opening credits play over this sequence, in which you are allowed to move around and look where you like. There are reports that many gamers back in the day didn’t actually realize that they were already in control of the protagonist — reports that they just sat there patiently waiting for the “cutscene” to finish, so ingrained was the status quo of bifurcation.

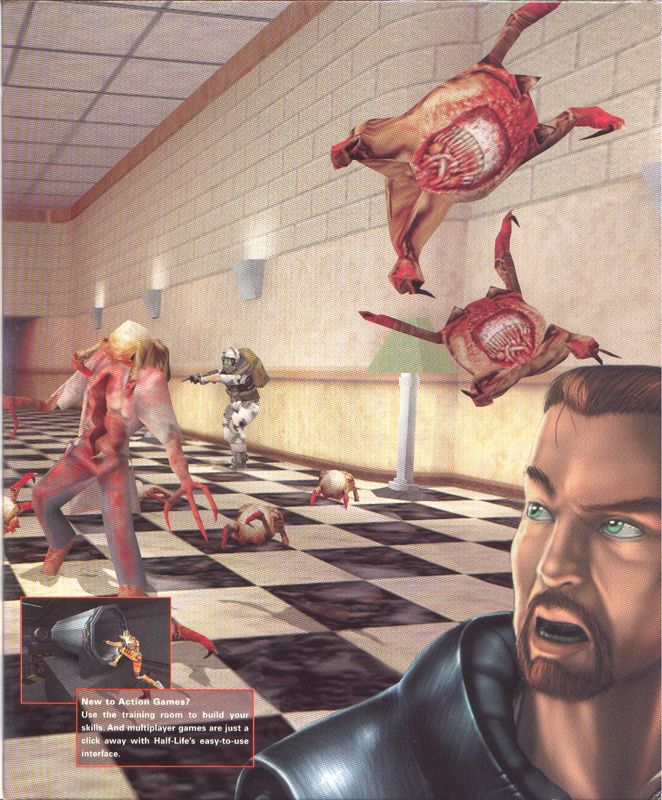

The protagonist himself strikes an artful balance between being an undefined player stand-in — what Zork: Grand Inquisitor called an “AFGNCAAP,” or “Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person” — and a fully fleshed-out character. As another result of Newell’s guiding rules, you never see him in the game unless you look in a mirror; you only see the world through his eyes. You do, however, hear security guards and colleagues refer to him — or, if you like, to you — as “Gordon” or “Mr. Freeman.” The manual and the intertitles that appear over the opening sequence of the game explain that his full name is indeed Gordon Freeman, and that he’s a 27-year-old theoretical physicist with a PhD from MIT who has been recently hired to work at Black Mesa. The game’s loading screen and its box art show us a rather atypical FPS protagonist, someone very different from the muscle-bound, cigar-chomping Duke Nukem or the cocky budding Jedi knight Kyle Katarn: a slim, studious-looking fellow with Coke-bottle eyeglasses and a token goatee. The heart of the computer-gaming demographic being what it was in 1998, he was disarmingly easy for many of the first players of Half-Life to identify with, thus adding just that one more note of immersion to the symphony. Small wonder that he has remained a favorite with cosplayers for decades. In fact, cipher though he almost entirely is, Gordon Freeman has become one of the most famous videogame characters in history.

The tram eventually arrives at its destination and a security guard welcomes you to the part of the complex where you work: “Morning, Mr. Freeman. Looks like you’re running late.” Passing through the double blast doors, you learn from your colleagues inside that it’s already been a rough morning: the main computer has crashed, which has thrown a wrench into an important test that was planned for today. Mind you, you don’t learn this through dialog menus, which Valve judged to qualify as taking control away from the player. You can’t speak at all, but if you approach the guards and scientists, they’ll say things to you, leaving you to imagine your own role in the conversation. Or you can stand back and listen to the conversations they have with one another.

You can wander around as you like in this office area. You can look in Gordon’s locker to learn a little bit more about him, buy a snack from the vending machine, even blow it up by microwaving it for too long. (“My God!” says your colleague in reaction. “What are you doing?”) All of this inculcates the sense of a lived-in workspace better than any amount of external exposition could have done, setting up a potent contrast with the havoc to come.

When you get bored fooling around with lockers and microwaves, you put on your hazardous-environment suit and head down to where the day’s test is to be conducted. It isn’t made clear to you the player just what the test is meant to accomplish; it isn’t even clear that Gordon himself understands the entirety of the research project to which he’s been assigned. All that matters is that the test goes horribly wrong, creating a “resonance cascade event” that’s accompanied by a lot of scary-looking energy beams flying through the air and explosions popping off everywhere. You’ve now reached the end of the second chapter without ever touching a weapon. But that’s about to change, because you’re about to find out that hostile alien lifeforms are now swarming the place. “Get to the surface as soon as you can and let someone know we’re stranded down here!” demand your colleagues. So, you pick up the handy crowbar you find lying on the floor and set off to batter a path through the opposition.

This was a drill with which 1990s shooter fans were a lot more familiar, but there are still plenty of new wrinkles. The scientists and guards who were present in the complex before all hell broke loose don’t just disappear. They’re still around, mostly cowering in the corners in the case of the former, doing their best to fight back in that of the latter. The scientists sometimes have vital information to share, while the guards will join you as full-blown allies, firing off their pop-gun pistols at your side, although they tend not to live very long. Allies were a new thing under the FPS sun in 1998, an idea that would quickly spread to other games. (Ditto the way that the guards here are almost better at shooting you in the back than they are at shooting the rampaging aliens. The full history of “allies” in the FPS genre is a fraught one…)

As you battle your way up through the complex, you witness plenty of pre-scripted scenes to go along with the emergent behavior of the scientists, guards, and aliens. Ideally, you won’t consciously notice any distinction between the two. You see a scientist being transformed into a zombie by an alien “head crab” behind the window of his office; see several hapless sad sacks tumbling down an open elevator shaft; see a dying guard trying and just failing to reach a healing station. These not only add to the terror and drama, but sometimes have a teaching function. The dying guard, for example, points out to you the presence of healing stations for ensuring that you don’t come to share his fate.

It’s the combination of emergent and scripted behaviors, on the part of your enemies and even more on that of your friends, that makes Half-Life come so vividly alive. I’m tempted to use the word “realism” here, but I know that Gabe Newell would rush to correct me if I did. Realism, he would say, is boring. Realistically, a guy like Gordon Freeman — heck, even one like Duke Nukem — wouldn’t last ten minutes in a situation like this one. Call it verisimilitude instead, a sign of a game that’s absolutely determined to stay true to its fictional premise, never mind how outlandish it is. The world Half-Life presents really is a living one; Newell’s rule of thumb was that five seconds should never pass without something happening near the player. Likewise, the world has to react to anything the player does. “If I shoot the wall, the wall should change, you know?” Newell said. “Similarly, if I were to throw a grenade at a grunt, he should react to it, right? I mean, he should run away from it or lay down on the ground and duck for cover. If he can’t run away from it, he should yell ‘Shit!’ or ‘Fire in the hole!’ or something like that.” In Half-Life, he will indeed do one or all of these things.

The commitment to verisimilitude means that most of what you see and hear is, to use the language of film, diegetic, or internal to the world as Gordon Freeman is experiencing it. Even the onscreen HUD is the one that Gordon is seeing, being the one that’s built into his hazard suit. The exceptions to the diegetic rule are few: the musical soundtrack that plays behind your exploits; the chapter names and titles which flash on the screen from time to time; those credits that are superimposed over the tram ride at the very beginning. These exceptions notwithstanding, the game’s determination to immerse you in an almost purely diegetic sensory bubble is the reason I have to strongly differ with Jeff Green’s description of Half-Life as an “interactive movie.” It’s actually the polar opposite of such a stylized beast. It’s an exercise in raw immersion which seeks to eliminate any barriers between you and your lived experience rather than making you feel like you’re doing anything so passive as watching or even guiding a movie. One might go so far as to take Half-Life as a sign that gaming was finally growing up and learning to stand on its own two feet by 1998, no longer needing to take so many of its cues from other forms of media.

We’ve about reached the end of our hour in Half-Life now, so we can dispense with the blow-by-blow. This is not to say that we’ve seen all the game has to offer. Betwixt and between the sequences that I find somewhat tedious going are more jaw-dropping dramatic peaks: the moment when you reach the exit to the complex at long last, only to learn that the United States Army wants to terminate rather than rescue you; the moment when you discover a tram much like the one you arrived on and realize that you can drive it through the tunnels; the moment when you burst out of the complex completely and see the bright blue desert sky above. (Unfortunately, it’s partially blotted out by a big Marine helicopter that also wants to kill you).

In my opinion, Half-Life could have been an even better game if it had been about half as long, made up of only its most innovative and stirring moments — “all killer, no filler,” as they used to say in the music business. Alas, the marketplace realities of game distribution in the late 1990s militated against this. If you were going to charge a punter $40 or $50 for a boxed game, you had to make sure it lasted more than six or seven hours. If Half-Life was being made today, Valve might very well have made different choices.

Again, though, mileages will vary when it comes to these things. The one place where Half-Life does fall down fairly undeniably is right at the end. Your climactic journey into Xen, the world of the aliens, is so truncated by time and budget considerations as to be barely there at all, being little more than a series of (infuriating) jumping puzzles and a couple of boss fights. Tellingly, it’s here that Half-Life gives in at last and violates its own rules of engagement, by delivering — perish the thought! — a cutscene containing the last bits of exposition that Valve didn’t have time to shoehorn into their game proper. The folks from Valve almost universally name the trip to Xen as their biggest single regret, saying they wish they had either found a way to do it properly or just saved it for a sequel. Needless to say, I can only concur.

Yet the fact remains that Half-Life at its best is so audacious and so groundbreaking that it almost transcends such complaints. Its innovations have echoed down across decades and genres. We’ll be bearing witness to that again and again in the years to come as we continue our journey through gaming history. Longtime readers of this site will know that I’m very sparing in my use of words like “revolutionary.” But I feel no reluctance whatsoever to apply the word to this game.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Rocket Jump: Quake and the Golden Age of First-Person Shooters by David L. Craddock, Masters of DOOM: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture by David Kushner, Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line by Ken Williams, and Game Design: Theory & Practice (2nd edition) by Richard Rouse III. Retro Gamer 149; the GamesTM special issue “Trigger Happy”; Next Generation of December 1998, April 1999, and June 1999; Computer Gaming World of June 1998, December 1998, and February 1999; Sierra’s newsletter InterAction of Fall 1997; Gamers’ Republic of September 1998.

Online sources include “Full Steam Ahead: The History of Valve” by Jeff Dunn at Games Radar, “The Final Hours of Half-Life 2” by Geoff Keighley at GameSpot, and Soren Johnson’s interview of Mitch Latsky on his Designer Notes podcast.

Where to Get It: Half-Life is available for digital purchase on Steam.

Sean Barrett

December 20, 2024 at 5:20 pm

“it’s hard to believe [Doom] was more popular than Windows”

The shareware version of Doom was everywhere. For example, it was on nearly every DOS computer at universities (and Windows computers ran on top of DOS), even if it wasn’t supposed to be. I suspect it’s not figurative at all.

Wikipedia says “It sold an estimated 3.5 million copies by 1999, and up to 20 million people are estimated to have played it within two years of launch.” Dunno how many it sold by 1996, but it would be unsurprising for shareware installs to be 10-20x larger.

Sean Barrett

December 20, 2024 at 5:22 pm

I mean to say “, or even (more likely?) 50x or 100x” but then forgot.

Sean Barrett

December 20, 2024 at 5:32 pm

Minor technical correction: Half-Life still had 8-bit textures, but it had a 16-bit output/display. Each texture can contain 256 different colors, but then the texture color is adjusted by the lighting (which can be colored). In games with 8-bit output, this is very limiting, as there aren’t enough unique display colors to distinguish all the texture colors, so image quality degrades quickly. Using 16-bit output allows all 256 colors to produce 256 different display colors for each degree of lighting, and makes colored lighting feasible in a way it never would be with 8-bit output.

Jimmy Maher

December 20, 2024 at 9:14 pm

Thanks!

Jimmy Maher

December 20, 2024 at 9:14 pm

Fair enough. Thanks!

Jason Dyer

December 20, 2024 at 5:50 pm

Half-Life is one of those games I’ve never finished and feel no regrets at all (I bailed at the alien planet jumping section).

I think everything before that is strong enough I wouldn’t make any cuts. I do think there’s value in having a mixture of intensity (you might try to just “keep the good scenes” but a lot of them wouldn’t hit as hard without the rhythm to how things appear).

Ahab

December 20, 2024 at 8:53 pm

I wouldn’t have cut anything before Xen either. IMO, Half-Life already has no filler, just peaks and troughs. Good pacing needs both; 100% nonstop energy like we see in modern Call of Duty is just exhausting.

I do wish Xen had been more polished, but I appreciate that they tried to close its campaign with something unfamiliar and weird. Even though it’s the low point, I’m happier that it exists in its current form than I’d be if it didn’t exist at all.

John

December 21, 2024 at 9:47 pm

I bailed in the exact same place. I suspect a lot of other people did too.

Frans

January 19, 2025 at 9:08 am

Gosh, I thought Half-Life had mostly become a terrible slog past the first half when the novelty had worn off, even though it had utterly amazed me by enemies throwing back grenades and flanking me (spoiler: I died :) ). The horrific tedium of the underground train, the only barely better cliff, etc. etc. only occasionally interspersed by something more interesting like a laser puzzle, and Xen is when it got fun again, perhaps especially the jumping. I didn’t care for the bosses though.

I’d broadly describe HL as worse Duke 3D (or perhaps, better executed Tek-War).

Infinitron

December 20, 2024 at 7:09 pm

I suppose the headcrab being inspired by the Alien facehugger was too obvious to mention?

David R

December 20, 2024 at 7:12 pm

Half-Life is one of my favorite games of the 90’s, despite the fact that I’ve never been able to finish the Xen level.

It’s not just the sense of immersion that I love, but the quality of the set-piece puzzles. For example, there’s an early level, “Blast Pit”, where you have to use sound to distract your enemies that is much more fun (and challenging) than the “find the blue key to open the blue door” puzzles that were common in more conventional FPS games.

The jumping puzzles are certainly a low point for the game though. I especially had trouble in a recent (partial) play-through remembering to use the “crouch-jump” to get to otherwise unreachable areas, and it is just really tough to do jumping puzzles in a first-person rather than a third-person perspective. (such as in Tomb Raider)

metzomagic

December 22, 2024 at 10:12 pm

I remember that I finished the Xen level, and thus the game, after many attempts with just 1 hit point remaining. Phew!

Vladimir Kazanov

December 20, 2024 at 8:01 pm

I think it is worth mentioning a few more things about Half-Life: numerous mods, total conversions, the Counter-Strike phenomena and the community magnum opus – Black Mesa.

Lt. Nitpicker

December 20, 2024 at 9:10 pm

I think Black Mesa is too far ahead in the blog’s timeline to justify more than a mention, but I feel that Half-Life’s modding community does deserve some kind of follow up, even if that entry happens when this blog begins to cover 1999 (when Half-Life modding started to heat up, including the first Beta of Counter-Strike and when Valve did the first Half-Life Mod Expo) or even 2000 (Counter-Strike’s official release)

Martin

December 22, 2024 at 3:40 am

The Total Conversion, They Hunger, was one of my faves.

Rich

December 22, 2024 at 4:35 pm

I’m not sure if there’s already been a post on mod communities in general? It was a huge scene in the late 90s & is probably deserving of one.

Ahab

December 20, 2024 at 8:26 pm

Regarding expectations – Half-Life changed my expectations 180. In early ’98, I was playing Final Doom with invulnerability cheats on the second-highest difficulty for maximum carnage and minimal resistance. Half-Life, though I played on easy, showed me the appeal of earning my victories, even if it meant surviving by the skin of my teeth. Maybe especially if it meant surviving by the skin of my teeth. There’s a particular thrill of fleeing a death pit of suppressive fire, finding tactically advantageous ground, and instinctively plugging an HECU grunt as he comes into view with your last magnum round moments before he can finish you off with a grenade or shotgun blast. At Half-Life’s best, combat encounters are a mixture of scripted and emergent moments that play out something like a deadly puzzle. I don’t think any shooter before it really had this quality, except maybe Rainbow Six, which I understand is much closer to a hardcore military sim than a conventional FPS, and that would be lost if its easy mode made gave you Doom-like bullet resilience.

Incidentally, Half-Life 2 gives you Doom-like bullet resilience on any difficulty level, and because of that I found it a bit disappointing.

JP

December 20, 2024 at 10:32 pm

4 titles from 1998 that are important to understand the profound “genre division” that FPS underwent that year:

* Half-Life: single player, story-focused roller coaster. While a lot of its descendants (up to and including modern Call of Duty etc) did and do have non-interactive cinematics, they clearly owe a greater debt to Half-Life than any other single game.

* Thief – the Dark Project: alongside its 1998 console counterpart Metal Gear Solid, the birth of the modern stealth game. Rich, intricate simulation, incredible atmosphere and world… I know first person games aren’t much your thing but I really hope you cover this one!

* Rainbow Six: a modern military theme, which believe it or not was rare in those days, that would soon overtake the genre – albeit with none of RB6’s simulationist trappings (including its entire “planning mode”).

* Tribes: multiplayer-first teamplay in open landscapes, with selectable character classes and a wide variety of gear. This design space had a huge heyday in the early 00s and its DNA is still visible today in things like Fortnite.

I actually think 1998 was the year everything came into place for the FPS to dominate the console market throughout the 00s. There would not have been a Halo, a Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, a Team Fortress 2, a Bioshock, or even a Portal without the great leap forward (in several different directions) that happened in 1998.

dusoft

December 26, 2024 at 5:45 pm

Also Delta Force that came out a couple months after Rainbow Six but had more external (open space) missions.

Keith Palmer

December 20, 2024 at 10:52 pm

There was supposed to have been a Macintosh port of Half-Life released not that long after the game first appeared, although it never materialised. Years later there a Mac port of the game did arrive on Steam, and I bought it, but perhaps having already played Halo and Portal kept me from going anywhere in Half-Life beyond finishing the tutorial level. After that, support for “32-bit applications” was removed from the Macintosh operating system, and that knocked out Half-Life. Then, with the thought you’d be getting around to this game, I did turn a slightly older computer into a “Linux box” to get Steam running on it and played through Half-Life’s tutorial level again, but once more never quite got around to starting the game proper…

If there’s a point to all of that, it’s the shameful admission that when you were describing “cowering scientists” and “hapless guards,” I was thinking of the panicking civilians and “defence drones” in Bungie’s Marathon; there was no “scripting” in that earlier game and not much in the way of “emergent behaviour,” though.

7iebx

December 21, 2024 at 3:12 am

Talking about Half Life without resorting to clichés is tricky. You did well.

I won’t bother even to try. Here are two:

1. Half Life was demonstrative proof to the industry that “show, don’t tell”, as a means to

flex immersive possibilities, applies to gaming every bit as much as to writing.

2. Half Life was gaming’s Citizen Kane. It breathed from within its medium, deploying sophisticated and untried storytelling manoeuvres so persuasively that its innovations seem obviousness now.

Having said that, as a game…well, it’s a good buddy that’s been around for years that’s still fun to hang out with now and then. But it ain’t marriage material, at least not for me.

Jimmy Maher

December 21, 2024 at 8:46 am

“Show don’t tell” is a great way of thinking about Half-Life’s innovations, so much so that I wish I’d said it. ;)

It’s not as universal a rule for good written storytelling as a lot of people — generally non-writers — think it is. A good novel is usually a careful blend of telling and showing; a good writer needs to be able to both cogently set the stage and put the reader *in* the scene.

But ludic storytelling had been coming down way too hard on the “telling” side before Half-Life. Half-Life was a somewhat radical experiment in taking the “showing” approach. Like most radical creative experiments, it was too extreme in its ideology to become the norm. But it demonstrated what was possible, and in doing so gave other games the opportunity to come closer to that aforementioned artful blend of approaches.

Greg

December 22, 2024 at 2:40 am

As you mentioned in the post, the historical narrative about the game has gotten a little confused as time’s gone on and what people truly cherish about the game is its total dedication to fully using the uniqueness of the medium to tell its story.

As I was reading the post, I was racking my brain trying to think of games that learned from and iterated from Half-Life and found just the right mix of showing and telling, as it were. (Deus Ex, maybe?) And this might just be me, but I’ve lamented the fact that games, especially in the time since Half-Life, have really just seemed to want to be a different kind of film/movie, with some going so far back to “telling” that the phrase “when do I get to play the game?” has become a cliche in its own right.

(Apologies if there are some glaring examples that I’m not remembering; turns out being over 40 does suck).

Jimmy Maher

December 22, 2024 at 10:55 am

The influence is subtler than a bunch of games that slavishly follow the complete Half-Life template — as I mentioned, very few games have pushed as hard to show rather than tell as Half-Life did — but it’s there. Although I’m the farthest thing from an expert on post-millennial gaming (these histories will increasingly become a journey of discovery for me as we move into that era), my impression is that endless expository cutscenes are far less prevalent today than they used to be. If you released a game like Wing Commander III or IV today, where the gameplay so obviously plays second fiddle to the cutscenes, I think that the critics would rip you a new one. Back in the 1990s, the critics were in a scramble to see who could praise those games most effusively as “the future of gaming.” Until, that is, Half-Life came along.

Gnoman

December 23, 2024 at 5:53 am

Cutscene-heavy games are still a pretty big thing. Not to the point they got in the “OMG FMV” days, but smash hits like GTA 5 have quite a lot of them.

This is not least because the Half-Life approach of doing things entirely in-engine while the player has control has pretty real limits in terms of telling a story.

stepped pyramids

December 26, 2024 at 3:44 am

Yeah, Half-Life’s knack for trapping you in a room where someone can monologue at you begins to stand out, just like the era in which it felt like every game had suspiciously long elevator rides to mask loading. I think that “even the game’s UI is diegetic” ended up being stickier than “no cutscenes” in the long term.

Seeker

June 10, 2025 at 5:59 pm

“Half-Life’s knack for trapping you in a room where someone can monologue at you begins to stand out” — that’s more of a Half-Life 2 thing, I think? Aside from the opening tram ride at the start and the G-Man’s monologue at the end, Half-Life 1 has a very light hand with trapping the player anywhere.

Vince

December 24, 2024 at 8:59 am

Yeah, the latest Indiana Jones game that just came out (and which has been generally well-reviewed) is full of minutes-long, noninteractive cutscenes. Yakuza is a successful series that is also known for using them liberally. Not to those extremes, but I would say most story-driven modern AAA games use them as the standard mean to advance the plot.

You could argue that Half-Life contemporary Metal Gear Solid, which effectively alternates between action set pieces and elaborate noninteractive in-engine cutscenes in almost equal measure, had as much influence in the evolution of games as Half-Life.

killias2

December 27, 2024 at 2:32 pm

I’d say a good example of the “show, not tell” approach in gaming is the Demon’s Souls/Dark Souls lineage. It doesn’t exactly follow Half Life (Demon’s Souls even has separate “levels”), but it’s broadly evidence that this approach continues to live and thrive. I mean, Elden Ring is so beloved, they put it’s DLC up for GOTY, haha.

killias2

December 27, 2024 at 2:37 pm

Also, it’s not exactly the same as control is taken away from the player, but the God of War semi-reboot had a whole thing where you see everything from a consistent perspective.

From Wikipedia: “Cinematographically, the game is presented in a continuous shot, with no camera cuts or loading screens.”

CdrJameson

December 23, 2024 at 8:30 am

Half Life even pushes into the even more games-y “do, don’t show” as you directly perform the actions that actually break everything.

Alex

December 21, 2024 at 7:42 am

Back in the day, Half-Life was probably one of the last shooters I´ve played before I lost interest in the genre for quite a while. I only remember that I beat it, but that´s about it. That´s being said, I also think that later shooters I really enjoy (F.E.A.R, the Metro-Series) wouldn´t have been possible without it´s influence.

Regarding Unreal, I still find it fascinating that a game so hyped back in the day somehow disappeared quite quickly without leaving much of a dent gameplay-wise (I´m refering to the original game, not to Tournament). I´ve never seen that kind of hype before and the marketing made a much deeper impression than the game itself.

Sarah Walker

December 21, 2024 at 9:32 am

Unreal’s an interesting game in many ways. The engine was obviously quite a leap forward, even from what Quake II was doing – I remember the first “outside” area being a showstopper at the time. It does a lot to build a coherent world; not quite on the level Half-Life does, but the levels do all link together in a mostly coherent way. And while it doesn’t have HL’s story telling chops, the System Shock-style of telling the story through logs works quite well.

Where it _doesn’t_ work, and why I think it vanished quite quickly, is in the shooting part of being an FPS. The combat in single player is outright miserable most of the time, with unsatisfying weapons and enemies that are either bullet sponges or capable of magically dodging bullets. I gather the multiplayer is similarly poor.

Unreal Tournament fixed all of this, and is a much better (and much better remembered) game as a result!

JP

December 21, 2024 at 7:55 pm

I tend to agree re: Unreal’s combat being the least interesting thing about it, it prompted me to make a “tourism” mod for it that led to the broader resource I maintain here: http://vectorpoem.com/tourism

Sarah Walker

December 21, 2024 at 9:54 am

I loved Half-Life at the time. Coming back to it more recently (I played through it again in 2023), the flaws are quite obvious. The platforming sections are ropey, the pacing is in parts pretty awful (the train section seemed to go on _forever_) and Xen is one of the most disappointing end sections to a game, tying with the “Many” area in System Shock 2 the following year.

Having said that, the combat is generally still of a very high standard, the story telling is still pretty good – though it’s telling that none of the non-player characters have names – and many of the set pieces are still excellent, such as the “Blast Pit” section mentioned above.

It’s also one of the first FPS games to ship with a level editor on the disc I think? I had fun playing with that at the time, more than with UnrealEd.

I think my favourite FPS from the era though is Quake II. Possibly because it’s trying to innovate less than many of the other games of the time (HL, Unreal, SiN etc), what it does do it does very well. And the story elements that it has, though much more limited than many other games of the time, are strong enough to greatly elevate it above its predecessor. Very much the last of its kind though.

Tonny

December 21, 2024 at 10:12 am

Thanks for the post.

You mentioned you spoke to the team about the regrets of Xen.

Did they have a bigger story and game play already outlined?

Is this the missing storyline between hl1 en hl2?

Side question: How do hl1 and hl2 line up, timeline wise?

Peter Parker

December 22, 2024 at 5:32 am

Hi Tonny

half life 2 plays 20 years after the events of the first game. Gordon Freeman was in stasis the whole time that is why the people react very astonished when they see Gordon Freeman not a day older than in half life 1.

I played HL2 again because of the 20th anniversary and I can confirm Jimmy Maher’s comment that HL1 is too long. HL2 has (obviously) much better pacing and is approx. half as long.

But also correct: the games were longer in the 90ies…

Sung

December 21, 2024 at 9:03 pm

Despite Half-Life’s legendary status, Steam has probably overtaken it many folds over now. It’s amazing how much influence, both culturally and economically, Newell has had on the video game frontier. At this point I don’t think it’s ridiculous to say that he’s at the same level as somebody like Shigeru Miyamoto of Nintendo…

As far as Half-Life goes…goodness, I think it was the hardest game I’ve ever played. And one of the scariest. When I got the Oculus, I played Half-Life: Alyx for a bit, really liking it…until I realized, wait, this game is going to have a ton of those horrible aliens! Delete!!

CdrJameson

December 23, 2024 at 8:26 am

Steam of course was originally just a system for delivering Half Life multiplayer patches in the background, so even that grew out of Half Life.

Gubisson

December 21, 2024 at 9:39 pm

“ about it way of presenting its story.” – about the way of presenting its story?

Jimmy Maher

December 22, 2024 at 10:59 am

Thanks!

John

December 21, 2024 at 10:10 pm

I didn’t own and didn’t have access to a proper gaming-capable computer when Half Life was released, so I don’t think I got around to playing it until, gosh, 2003 or so, when I finally bought myself a beefy laptop with a discrete GPU. Half Life was the first FPS I’d played since Quake and I have to say that it was something of a revelation. I don’t recall being particularly impressed by the graphics or even necessarily the atmosphere. (Quake has its faults, to be sure, but a lack of atmosphere is not one of them.) I do remember being impressed by just how rarely I got lost or confused. I mean, it happened–see, for example, Xen–but it happened way less often than I remember it happening in Quake, Doom, or Wolfenstein. I don’t often dip back into the FPS genre, but whenever I do I’m so very glad that Half Life brought the era of twisty, maze-like levels, color-coded key cards, and lots and lots of backtracking to its well-deserved end.

WellTemperedClavier

December 22, 2024 at 3:47 am

I appreciate how you drew the distinction between plot and presentation. Because as you say, Half-Life’s plot is actually pretty basic. But a simple story presented well is better than a complex one presented poorly, and that’s a big part of why it shook things up.

Since you mentioned some of Half-Life’s antecedents and inspirations, I wanted to mention an older FPS that actually did some of the same things Half-Life did: Bungie’s Marathon Trilogy. Marathon also worked to incorporate story into the gameplay. For instance, while it had plenty of the same “find the switch” missions that populated Doom, it’d usually provide a storyline reason for finding and flipping said switches. For instance, the switches will activate some automated defense drones that’ll help you (and indeed, those drones will appear in future missions to help you shoot the aliens). It’d even go to some pretty impressive lengths for immersion; for instance, you could not find any ammunition for your weapons on the levels that take place on the alien ship. Why? Well, because alien ships obviously wouldn’t carry ammunition for human weapons (though by that point, you should be well-stocked enough that this isn’t a serious problem). Marathon also pioneered weapons with multiple fire modes, mouse-look for aiming, and level verticality.

The reason Marathon isn’t that well-known is simply because it was exclusive to Macs (except for the second game, which would get a quiet Windows release, and the whole thing is now legally free online). Of course, Bungie would later go on to great fame with the Halo series.

Despite being so ahead of its time, I’m not sure Marathon’s aged as well in terms of gameplay. The level design can be pretty maze-like, more so than Doom’s, and like Half-Life it suffers from some platforming sections (made worse by the fact you can’t jump; instead, you have to do this awkward running-fall type of thing). The second and third games have some pretty dreary underwater sections. At the same time, it did a lot of things right and was quietly influential in its own way.

Alex

December 22, 2024 at 7:17 am

Regarding maze-like levels: After buying both Dark Forces and Jedi Knight for pocket money a few weeks ago and applying texture mods, I was so relieved to find out that both games now have an automap that I could actually read. My motivation to beat both games was immediately raised.

Knurek

December 23, 2024 at 7:40 am

This may sound sacrilegious to some people, but only was able to enjoy Half-Life when I played the Black Mesa reimagining – props to Valve for allowing that to happen, unlike most other companies who’d send a C&D without a second thought.

But I enjoyed watching my brother play the game – it was my method of choice for FPS games, since most of them did (and still do) give me motion sickness anytime I tried playing them.

Vincent Kinian

December 23, 2024 at 8:52 pm

There are a number of things I could comment on regarding Half-Life: how its creators and its fans understand gameplay, narrative, and the relationship between them; the many examples of games that had already developed the relationship between gameplay and narrative, whether outside Half-Life’s genre or within it. However, what sticks out to me the most is how much continuity there is between it and its predecessors. For as much as it’s held up as this break from what came before it, its developers seem to have been just like the competition in paying more attention to/hyping up more the technological apparatus through which they were presenting their game than the narrative that game was premised on, EG presenting themselves at the 3DFX booth at E3, as though the graphical prowess was the draw. Likewise, the strategy of conveying narrative – or atmosphere, if you want to hew closely to Valve’s ideas about gameplay and narrative – largely through space, like Half-Life does, goes all the way back to Wolfenstein 3D.

Gordon Cameron

December 23, 2024 at 9:09 pm

I played Half-Life in 1999. It astonished me then, and remains one of my favorite games. I replay it frequently, and think it has aged fine – although my perspective on ‘aging’ and ‘dating’ in videogames is becoming increasingly idiosyncratic.

Playing the game at the time, the vent-crawling didn’t feel like padding. It was a constant building of tension, punctuated by the next room you’d uncover. I think, upon much consideration, my favorite level might be ‘We’ve Got Hostiles’, in which the crawling-through-vents, low-level stuff slowly transitions to the big confrontations with the grunts. One level I do think goes on a bit too long is ‘Surface Tension,’ though it also has its standout setpieces. Even the jumping puzzles never really bothered me. Sure, FPS games aren’t ideal for that style of gameplay, but excepting a couple bits in ‘Lambda Core’ I never found them particularly frustrating. And a level like ‘Residue Processing’ served an excellent function in long-term pacing.

As a straight-up shooter, the game shines with the depiction of the enemy grunts; their tactical AI is still impressive. The aliens aren’t especially challenging, but seeing a head crab far away still gives me a bit of a chill. There’s some cheating with monster spawn-ins at scripted points.

I don’t hate the Xen levels. They could have been longer and more developed, but that’s what the Black Mesa remake does, and by then it starts to overstay its welcome. The moment we jump into Xen I think it’s clear we are in the final act and there isn’t a lot of gameplay left. But for my part, that’s fine, and Nihilanth is a striking final boss encounter. I think the ending would have been disappointing without something like Xen, without some left turn into real strangeness to cap it all off.

I agree that the game’s story has been oversold. Obviously ‘science experiment goes horribly awry’ with lurking X-Files G-man isn’t stunningly original, and as with most FPS’s, there aren’t really any characters. But I lean more to Carmack’s view on story in such a game, I guess. What Half-Life excelled at was atmosphere, a sense of place, and a total integration of the gameplay elements with the mood. And the memorable set pieces – like the justly celebrated opening tram ride, or descending an elevator as head crabs drop down onto you, or the room full of trip-mines wired to blow up a nuclear warhead. (Though I struggle to find any in-universe reason why someone would have set that up, unless one of the grunts was straight up suicidal.) It also (as CGW discussed at the time) innovated the concept of a ‘boss fight’ by having the ‘boss’ permeate a level rather than just pop up at the end — seen particularly in Blast Pit and the ‘Surface Tension’ helicopter. The flip side of this is that when you actually confront said bosses, it’s not really a fight at all — more the final conclusion of a puzzle. Which can be a bit anticlimactic.

All in all, HL1 is still my favorite single player FPS, by a pretty long margin. I think it’s much better than its sequel, though I enjoyed that as well. My personal shooter trinity would probably be Half-Life, Jedi Knight, and Unreal. It’s interesting that they all came out within about an 18-month span. It was a heady time.

dusoft

December 26, 2024 at 12:06 am

“reports that they just sat there patiently waiting for the “cutscene” to finish, so ingrained was the status quo of bifurcation.”

I can confirm I was waiting patiently through the intro and only by an accident moved a mouse and suddenly found out you can change your point of view. We were so used to “static” intro and cut scenes that it didn’t even occur to us this was already part of the game.

jsn

December 27, 2024 at 12:15 am

> …charge a punter $40 or $50 for a boxed game…

Punter?

Mark Williams

December 27, 2024 at 9:23 am

‘Punter’ is a common British slang term for a purchaser.

jsn

December 28, 2024 at 5:00 pm

Ah, thanks. I ought to have known; Jimmy does like him some British now and then.

C’mon Jimmy, using that term in the context of being charged “$” is just obscure, man! :)

James Turley

December 30, 2024 at 1:15 pm

I think you brush over it a bit but one of the things that really was a breakthrough in half life was the enemy AI. The fact that particularly the human enemies would work together and react to things like grenades was unprecedented in the genre AFAIK. Unreal attempted to make things harder for you but basically did it by nerfing the guns and giving some enemies cheat reflexes. Half life did it the right way, which I think massively strengthened the plot-gameplay bond from the ‘gameplay’ side. Nothing in the core combat mechanisms broke you out of the suspension of disbelief.

Also, there are two bosses in Xen – who could forget Gonarch, eh?

Jimmy Maher

December 30, 2024 at 1:58 pm

Yeah, you’re right about Xen, of course. Thanks!

Gordon

January 7, 2025 at 7:37 pm

I am a bit disappointed with your write up as it sadly fell to the mythical overhyped status of Half Life.

First, I will quickly prove the “mythical overhyped” claim – over the past year Half Life has been averaging around 1000 players per month (https://steamcharts.com/app/70), while revolutionary games like Sin average 0 players (https://steamdb.info/sub/416313/). Even your mentioned Jedi Knight: Dark Forces 2 averages only around 20 (https://steamdb.info/app/32380/charts/). These vast chasms in player difference prove Half Life is receiving disproportionately underserved attention.

Second, all “innovations” Half Life brought have actually been done before – its just again the disproportionate attention Half Life sucks away from other pc games unfairly make it seem innovative.

For example, Cybermage: Darklight Awakening used the “show don’t tell” approach extensively – it features extensive in-game dialogue all without cutscenes and within the protagonist’s perspective just like Half Life but 3 years earlier and arguably done even better.

Sin also used extensive in-game dialogue/storytelling without cut-scenes, and also featured extensive set pieces – all again done before Half Life’s release.

Deus had a continuous in game fully 3D first person word (within similar hidden loading techniques like Half Life but perhaps don even better) 2 years before Half Life release.

Strife arguable also used a “show don’t tell” approach – interactions with NPCs were pseudo first person and not cutscene based.

I could go on and on but its pointless because this post wont get any traction. Someone with knowledge of pc history should do a book that finally debunks the Half Life myth and maybe even interview some the former HL developers who will privately likely admit there was minimum actual innovation in HL.

Mike Taylor

January 8, 2025 at 4:43 pm

“Over the past year Half Life has been averaging around 1000 players per month, while revolutionary games like Sin average 0 players [and] Jedi Knight: Dark Forces 2 averages only around 20. These vast chasms in player difference prove Half Life is receiving disproportionately underserved attention.”

… Or perhaps these stats indicate that Half Life is indeed a classic.

Daniel Nava

February 24, 2025 at 12:35 am

This post js reads like you didn’t like half-life, and no offense if you don’t like that I’m assuming, but Half-Life was mainstream innovation, people credit Carti for producing a new genre of Rage Rap but Carti had to hear some form of that sound to create what he wanted. Sure, these games existed a couple of years before HL and feature some of the things we list as innovations, but its because this game came at a unique level of polish for its time. Its skeletal mesh system, set-pieces, and just pushed the fps run-and-gun genre at the time to a new level that I don’t think we’ve ever seen.

Daniel Nava

February 24, 2025 at 12:36 am

Also, I dislike how you mess with history in your comment, it’s commonly known by the HL1 anniversary documentary that someone from Valve namechecks Sin as direct competition, they came out side by side dude.

Dmitry Mazin

February 24, 2025 at 9:16 am

Mike Harrington commented! (https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=43151266)

> Nice writeup. FWIW, I never saw Michael Abrash wear a tie. :)

>

> We were very into 3D cards back then. We had a lot of ties to that part of the world. I had been doing video drivers for OS/2 and NT. I got to know Abrash from his writing on the VGA, 8514, and, of course, asm. At Valve, we hired a couple of great guys from 3dfx. I still have a 3dfx hat somewhere that I bust out on special occasions. The killer setup back then was hooking up two 3dfx cards (SLI). But I usually played on a standard card because I wanted/needed to see it run like most people would experience it.

>

> We had a deal with one of the companies, maybe 3dfx, but I forget who, to include the first three levels of HL with their card. Even though the game wasn’t anywhere near finished, we sent off a disk to the company with our first three finished levels so we could get paid. Somehow, it leaked. We were pissed at first, but then it took off. People loved it. It really gave us the confidence that we were on the right track. It was our first game. The validation was just what we needed.

>

> Fun times.