In January of 1995, Electronic Arts bought the prestigious British games studio Bullfrog Productions for an undisclosed sum that was rumored to be in the neighborhood of $45 million. The lives of the 35 or so people who worked at Bullfrog were transformed overnight. Peter Molyneux, the man who had built the studio’s reputation on the back of his “god game” Populous six years earlier, woke up the morning after the contract was signed with real money to spend for the first time in his life. For him and his colleagues, the new situation was gratifying, but also vaguely unsettling.

The acquisition came with all of the expected rhetoric from EA about “letting Bullfrog be Bullfrog.” Inevitably, though, the nature of the studio’s output changed in the years that followed. EA believed — and not without evidence — that series and brands were the key to long-term, sustainable success in the games industry. So, it encouraged or pressured the folks at Bullfrog to connect what they were doing now with what they had done before, via titles like Magic Carpet 2, Syndicate Wars, Populous: The Beginning, and Theme Park World. Iteration, in other words, became at least as prized as the spirit of innovation for which Bullfrog had always been celebrated.

And where the spirit of innovation refused to die, you could always do some hammering to make things fit. The most amusing example of this is one of the two best remembered and most beloved games to come out of this latter period of Bullfrog’s existence. What on earth could be meant by a “theme hospital?” EA couldn’t have told you any more than anyone else, but the name sounded pretty good to it when one considered how many copies Theme Park had sold the year before the acquisition.

Theme Hospital was born as one of about a dozen ideas that Peter Molyneux wrote on a blackboard during the heady days just after the acquisition, when Bullfrog had a mandate to expand quickly and to make more games than ever before. This meant that some of the Bullfrog old guard got the chance to move into new roles that included more creative responsibility. Programmer Mark Webley, who had been doing ports for the studio for a few years by that point, thought that Molyneux’s idea of a simulation of life at a hospital had a lot of potential. He plucked it off the list and got himself placed in charge of it.

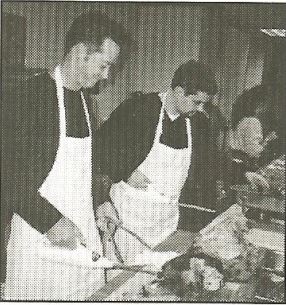

In the beginning, he approached his brief with a measure of sobriety, not a quality for which Bullfrog was overly known. He even thought to do some field research at a real hospital. He and visual artist Gary Carr, the second person assigned to the team, talked the authorities at Royal Surrey County Hospital, conveniently located right next door to Bullfrog’s offices in Guildford, England, into giving them a behind-the-scenes tour. It proved rather more than the pair had bargained for. Videogame violence, which Bullfrog wasn’t noted for shying away from, was one thing, but this was something else entirely. The two young men were thrown out of at least one operating theater for retching. “I remember we watched a spinal operation one morning, which was bad enough,” says Carr. “Then the person who had been assigned as our guide said, ‘Alright, after lunch we can pop down to the morgue.'” It was right about then that they decided that an earnest simulation of life (and death) at a National Health Service hospital might not be the right way to go. They decided to Bullfrog the design up — to make it silly and irreverent, in Bullfrog’s trademark laddish, blackly humorous sort of way. “It’s not about how a hospital runs,” said Mark Webley sagely. “It is about how people think [it] runs.”

Webley played for a while with the possibility of making Theme Hospital a sort of satirical history of medicine, from the Middle Ages (“when curing people usually meant hacking their legs off with a bloody great saw, covered in leeches”), through the Victorian Age (“lots of mucking about with electric shocks and the like”), and on to the present and maybe even the future. In the end, though, that concept was judged too ambitious, so Theme Hospital returned to the here and now.

That said, the longer the slowly growing team worked, the less their game seemed to have to do with the real world of medicine that could be visited just next door. A former games journalist named James Leach came up with a matrix of absurd maladies: Bloaty Head (caused by dirty rainwater and putrid cheeses), Broken Wind (caused by too much exercise after a big meal), Slack Tongue (caused by too much vapid celebrity gossip), Infectious Laughter (caused by hearing too many sitcom laugh tracks), King Complex (afflicting Elvis impersonators who spend too much time in character). The cures are as imaginative as the diseases, generally involving slicing and dicing the patients/victims with one or more horrifying-looking Rube Goldberg contraptions. Theme Hospital is healthcare as those with a deathly fear of doctors imagine it to be.

The finished game is deceptively complex — perhaps a little too much so in my opinion. You start each scenario of the campaign with nothing more than a plot of land and a sum of starting money that never seems to be enough. You have to build your hospital from scratch, deciding where to place each and every room, and then where to put everything that goes inside each room, from the reception desk to the toilets to the even more important soda and candy machines. (This is most definitely not socialized medicine: your hospital is expected to make a profit.) Then you have to hire doctors, nurses, janitors, and administrative personnel from a wide variety of applicants. Figuring out how best to fiddle the countless knobs that affect the simulation requires considerable dedication; every input you make seems to result in a cascade of advertent and inadvertent consequences. Once the action really starts to heat up, Theme Hospital can become as frenzied as any session of Quake or Starcraft. Keeping the pot from boiling over in the midst of an epidemic or a disaster — events that become more and more frequent as you progress further — requires constant manual intervention, no matter how efficiently you’ve laid out your hospital and how judiciously you’ve selected its staff.

Your reaction to all of this will depend on two factors: whether you’re someone who is inherently drawn to open-ended simulations of the SimCity and Theme Park stripe, and whether Bullfrog’s brand of humor causes you to come down with your own case of Infectious Laughter. My answer to both of these questions is a qualified no, which makes Theme Hospital not really a game for me. By the time I’d played through the first couple of scenarios, I could see that the ones to come weren’t going to be all that different, and I just didn’t have the motivation to climb further up the campaign’s rather steep ladder of difficulty. Speaking of which: the campaign is as rudimentary as the simulation is baroque. Each of its scenarios is the same as the one before, only with more: more diseases to cure, more requirements to meet, more pressure. It left me with the same set of complaints I recently aired about the campaign in Rollercoaster Tycoon: I just wish there was a bit more there there, an attempt to provide a more interesting and diverse set of challenges that entailed less building of the same things over and over from scratch.

But, just as was the case with Rollercoaster Tycoon, the game about which I’m complaining today did very well for itself in the marketplace, an indication that plenty of people out there don’t share my peculiar preferences. (Who would have thought it?) Released in the spring of 1997, Theme Hospital was by all indications Bullfrog’s biggest single latter-day commercial success, a game which continued to sell reasonably well for several years, sufficient to reach the vicinity of that magic number of 1 million units. In the process, it became sneakily influential. You don’t have to squint too hard to see some of the DNA of Theme Hospital in the more casual time-management games that became crazily popular about ten years on from it.

Dungeon Keeper’s box sports its mascot, the Horned Reaper. Or, as the lads at Bullfrog preferred to call him, Horny.

The other widely acknowledged classic from this period of Bullfrog’s history took even more time and effort to make than Theme Hospital. In fact, Dungeon Keeper — one does have to breathe a sigh of relief that EA’s marketers didn’t insist that it be called Theme Dungeon! — had the most extended and torturous development cycle of any game Bullfrog ever made.

The idea for Dungeon Keeper came to Peter Molyneux some time before the EA acquisition: in mid-1994, when he had just finished up work on Theme Park.

I was sitting in my car in the middle of a traffic jam. I was bored to tears, waiting for the cars in front to begin moving again. Then the idea of a reverse role-playing game popped into my head. Yes, I thought, this could be a good game. You could have loads of monsters crawling around deep, dark tunnels. You could have the power to control them directly, deal with all their problems and petty grievances. As your dungeon grew, your power would increase. You could mine and hoard gold and have to put down rebellions. On top of all this, you could have the traditional heroes invading the trap-laden dungeon you’d created. I was so deep in thought, I hadn’t realized the traffic had cleared.

Dungeon Keeper was a set of answers to questions that some of the more literal-minded players of Dungeons & Dragons and its ilk, whether played at the tabletop or on computers, had been asking for many years already. Just what was up with those nonsensical labyrinths filled with creatures, traps, and treasure that seemed to be everywhere in the worlds of Greyhawk and the Forgotten Realms? What was the point of them? For that matter, what did all those monsters eat while they were hanging out waiting for the next group of adventurers to come by? And what was it like to be the evil wizard with the thankless job of taking care of this lot?

Peter Molyneux, who called CRPGs “my favorite type of game” even though he had never made one, proposed to find some answers now by approaching the genre from the opposite point of view from the norm. It was one of the most brilliant conceptions he ever came up with: quick and easy to explain to just about anyone who knew anything about computer games, and at the same time something no one had ever attempted to do before. And it was as on-brand as could be, gently transgressive in that trademark Bullfrog way. Molyneux:

You have to hire monsters and keep them employed. How do you keep a monster employed? There are basically two ways to motivate your staff. The first is basically to pay them money, but you really don’t want to do that. The second and preferred method of influence is fear. Say you have a band of ten goblins and you want to maintain their loyalty. What’s the best way to do that? Kill off five of them. Ritual sacrificing is really important. You have to prove to the people below you that you’re evil. This is a dungeon, after all.

When the acquisition negotiations began, Molyneux was already tinkering with Dungeon Keeper alone. He was joined by a second programmer, Simon Carter, in November of 1994. EA loved the idea; in the wake of DOOM, dark and gritty violence was in in games. The two-man project may have been in its infancy, but it was a major selling point for Bullfrog during the talks with EA, who saw it as a game with the potential to become huge.

Alas, after the deal was done EA promptly started to pull Molyneux in way too many directions for his liking. He was given a set of executive titles and the executive suite to go along with it, removing him from the day-to-day work in the trenches.

There was me, this passionate sixteen-hour-a-day coder, who kind of lived with these other blokes who were in the office, and all of a sudden Electronic Arts came in and said, “Okay, right. We think you’re fantastic, and we want to expand your studio, and rather than one game [per year] we can get five games out of you.” The company literally went from 35 people to 150 people in nine months, and suddenly there were all these strangers there. Then they said to me, “We think you’re fantastic. We’re going to make you head of our studio in Europe,” and part of me was thinking this was amazing — these people really think I’m clever — but there was another part of me that felt awful, that this was alien and horrible to me. The foundation stones of my work completely changed…

A man with an obsessive-compulsive relationship to the games he made, who would increasingly acknowledge himself to be neurodivergent in later years, Molyneux was painfully ill-equipped for the role of a glad-handing EA vice president; it just made him uncomfortable and miserable. He was forced to oversee Dungeon Keeper — his own baby! — from afar. “I didn’t have time to look at games,” he says. “I was walking in, spending half an hour with them, and then walking out. That was the worst period of my life. Bullfrog was everything to me, and suddenly I was this character that would have to walk into a room and make instant judgments about things.”

From the beginning of 1995, Dungeon Keeper was extravagantly hyped in the gaming press, which ran preview after preview. This gives us an unusual insight into the stages of its evolution. For example, a preview published in the American magazine Computer Games Strategy Plus in the fall of that year describes a heavy focus on multi-player action. At this point, Dungeon Keeper sounds almost like a proto-Diablo, with the important twist that one player is allowed to be the mastermind of the dungeon itself. For those on the side of Good, “one strategy for building up your character would be to enter the dungeon, kill off a few creatures, and run away. Return later (fully healed, but at a cost), kill a few things, and run away again. Stats are kept for the usual physical attributes as well as experience and monsters killed. One interesting feature will allow players to take their saved [character] with them to other people’s dungeons as well.” A player character who conquered a dungeon’s overlord would have the option to come over to the side of Evil and take his place.

In truth, however, progress throughout 1995 was slow and halting, a matter of two steps forward and one step back — and sometimes vice versa. “We spent quite a bit of time just messing around with the idea, but not getting very far in terms of a design,” admits lead artist Mark Healey. Dungeon Keeper may have had a brilliant core concept, but there was no clear vision of how that concept would be implemented, of what kind of game it would ultimately be at the gameplay level. Was it primarily a puzzle game, a kind of Tower Defense exercise where you had to set up your monsters and traps just right to fend off a series of different heroes? Or was it an open-ended sandbox strategy game, a SimCity — or Theme Park — in a dungeon? Or was it, as Strategy Plus dared to write, a game “which may redefine the role-playing genre”? At one point or another, each of these identities was the paramount one, only to fall back down in the pecking order once again. Programmer Jonty Barnes, who was responsible for the Dungeon Keeper level editor, left Bullfrog in the summer of 1995 to finish up his degree at university. He claims that when he rejoined the team a year later the game had “reset. It was back to where we were when I’d left off.”

Be that as it may, the inflection point for the project had already come and gone by then. EA was extremely disappointed when Dungeon Keeper failed to ship in time for the Christmas of 1995, to supplement a Bullfrog lineup for the year that otherwise included only the under-performing Magic Carpet 2 and the thoroughly underwhelming racing game Hi-Octane — a poor early return indeed on a $45 million investment. Management started to make noises about cancelling Dungeon Keeper entirely if it didn’t show signs of coming together soon. Meanwhile Peter Molyneux was as miserable as ever: “I still really love games, and I hate what I’m doing at the moment.” He thought about resigning, then trying to find or found another company where he could make games like he had in the old days, but he couldn’t bear to lose all influence over Dungeon Keeper. And as for seeing his baby axed… well, that might just send him around the bend completely.

So, at the beginning of 1996, he went to the rung above him on the EA corporate ladder with a modest proposal. He’d had enough of meet-and-greets and wining-and-dining, he told his bosses forthrightly. He wanted to quit EA — but first he wanted to finish Dungeon Keeper. He wanted to climb back down into the trenches and make one last amazing game before he said farewell. EA scratched its collective head, then said okay — on two additional conditions. He couldn’t make his game from the Bullfrog offices, where he would be privy to inside information about the other projects going on and might, it was feared, try to poach Bullfrog employees for whatever he decided to do after Dungeon Keeper. He would have to find another spot for the team to work from. And naturally, he couldn’t tell the public that he was leaving the studio with which he was so closely identified until Dungeon Keeper was done. This sounded reasonable enough to Peter Molyneux.

He didn’t have to look far for a new workspace: he simply moved the core of the team — consisting of no more than half a dozen people — into a space above the garage at his house.[1]Some details of the arrangement — namely, the financial side — remain unclear. Molyneux has claimed in a few places that he paid for the rest of Dungeon Keeper’s development out of his own pocket in addition to providing the office space, but he is not always a completely reliable witness about such things, and I haven’t seen this claim corroborated anywhere else. Suddenly it was like the old days again, just a small group of friends working and playing together for a ridiculous number of hours each day to make The Best Game Ever. The team effectively became Molyneux’s roommates in addition to his colleagues. Jonty Barnes:

We would play the game at night drinking beers, arguing over who should have won based on how the game should be versus the way it was. If somebody won too easily, we could change the design the following day, and that really honed the intensity and the strategy of building Dungeon Keeper. We ended up working pretty much six or seven days a week for a long period of time, but we didn’t notice because we cared so much about what we were creating.

Over these endless hours of work and play, the what of the game slowly crystallized. Certain elements of the puzzler were retained: each scenario of the campaign would require you to fend off attacks by one or more avatars of Good. Ditto some elements of the CRPG, whose legacy would take the form of the ability to “possess” any of the monsters in your dungeon, running around and fighting from a first-person view. At heart, however, Dungeon Keeper would be a management strategy game, all about setting up and running the best dungeon you could with the resources to hand. It would borrow freely not only from the likes of Theme Park (and now Theme Hospital) but also from the more straightforwardly confrontational real-time-strategy genre that was exploding in popularity while it was in development.

Despite the jolt of energy that accompanied the move into Molyneux’s house — or perhaps because of it — work on the game dragged on for a long, long time thereafter. The Christmas of 1996 as well was missed, while EA’s bosses continued to shake their heads and make threatening noises. At last, just a few weeks after Theme Hospital had shipped, Molyneux and company declared Dungeon Keeper to be finished. True to his word, Bullfrog’s co-founder, leading light, and heart and soul officially resigned on that very day. “Dungeon Keeper is my final game for Bullfrog, and this is part of the reason I wanted to make it so good,” he told a shocked British press. “It’s a sort of goodbye and thanks for all the great times past.”

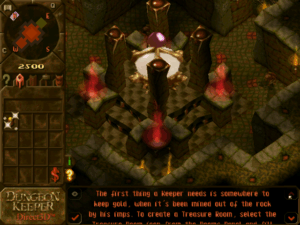

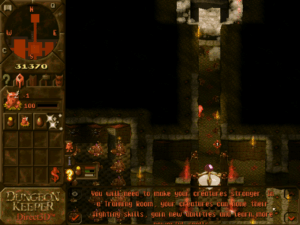

You start each scenario with only a Dungeon Heart. You must protect this nerve center and in particular the orb it contains at all costs, for if the orb is destroyed, you die instantly.

Keeping a dungeon turns out to be a bit like keeping a zoo. You need a Hatchery to provide food for your minions, in the form of hordes of woebegone chickens.

Each type of monster also needs its own Lair to retreat to. (It turns out that a lot of these creatures don’t like each other very much.)

The second scenario introduces the Training Room, where you can “level up” your monsters in exchange for gold.

The third scenario introduces the Library, where you can research spells with which to smite your enemies (or your minions). The campaign continues in this vein, layering on the complexity piece by piece.

When he looks back upon his career, Peter Molyneux tends to be a harsh critic of his own games. Dungeon Keeper is no exception: “It had a lot of things wrong with it. Too many icons. Too many game mechanics that were just wrong. It ended up being too dependent on little bits that were supposed to be there as jokes. In the end, I didn’t feel as proud about it as I had hoped.”

Very few people have agreed with this assessment. In its heyday, Dungeon Keeper enjoyed the best reviews of any Bullfrog game in years, outdoing even Theme Hospital in that respect. (Combined, the two titles created a real if fairly brief-lived “Bullfrog is back!” frisson.) Computer Gaming World called Dungeon Keeper “a damned fine creation. Its utter uniqueness and sense of style alone are worth the price, especially in these days of recycled inspiration. It’s a true gamer’s game — tremendously deep, demanding, and open to exploration.” GameSpot deemed Dungeon Keeper “among the best games released so far this year, and any fan of real-time strategy or classic fantasy role-playing games should run right out and buy this game. Hopefully, this is the new face of Bullfrog…”

Sales were solid, although not quite as strong as the reviews — not to mention EA’s early expectations — might have led one to believe. The game’s Achilles heel, to whatever extent it had one, was a dated presentation, a byproduct of the long development cycle and the small development team. It was among the last slate of games to be targeted at MS-DOS rather than Windows, and its muddy, pixelated graphics, caked with enough brown sauce to recreate the Mona Lisa, looked to be of even lower resolution than they actually were. At a glance, Dungeon Keeper looked old and a bit dull, in a milieu obsessed with the new and shiny. (Theme Hospital was another MS-DOS anachronism, but its brighter color palette and cleaner aesthetics left it looking a lot more welcoming.)

But if you can get beyond the visuals, Dungeon Keeper goes a long way toward living up to the brilliance of its central conceit. If the first half of its development cycle was one extended identity crisis, the creators more than figured out what identity their game should have by the time that all was said and done. Its every element, from the silkily malevolent voiceovers by the actor Richard Riding, who sounds like all of Shakespeare’s villains rolled into one, to the countless little sadistic touches, like the way you can slap your minions with your big old claw-like hand to get them working faster, serves to justify the marketing tagline of “Evil is Good.” Even if you’re someone like me who genuinely prefers to be the good guy in games, you can’t help but admire Dungeon Keeper’s absolute commitment to its premise. And for those who do like the idea of playing the dark side more than I do, this game is the perfect antidote to all of those CRPGs that claim to let you do so, only to force you to do the right thing in the end for the — horror of horrors! — wrong reason. (A whole Parisian salon worth of existentialist philosophers would like to have a word with those game designers about the real nature of Good and Evil…) There’s no such prevarication in Dungeon Keeper; your intentions and your deeds are in complete harmony.

For my part, I enjoyed the game more than I really expected to — in fact, more than any other Bullfrog game I’ve played in the course of writing these histories. It helped immensely that Dungeon Keeper marks the point where Bullfrog finally gave us a proper, bespoke campaign, complete with a modest but effective spine of story, which sees you corrupting a succession of goodie-goodie realms with sticky-sweet names like “Eversmile.” The first half in particular of the 20-scenario campaign is one of the best of this era of gaming. Unlike a lot of earlier Bullfrog games, which were content to throw you in at the deep end, Dungeon Keeper starts off with just a handful of elements, then gradually layers on the complexity scenario by scenario, introducing new room types, new monsters, and new spells in a way that feels fun rather than overwhelming. The game plays quickly enough, and the scenarios are varied enough, that having to start over and build a new dungeon from scratch each time feels tempting rather than punishing. You’re always thinking about how you can build the next one better, thinking about how you can integrate the new elements that are introduced into what you’ve already learned how to do. It’s enough to win over even a middle-aged skeptic like me, whose heart isn’t set all aflutter by the transgression of being Evil.

Unfortunately, the happy vibes came to a crashing halt when I hit the tenth scenario of the campaign. Here the game breaks with everything the previous nine scenarios have been painstakingly teaching you; suddenly it’s not about constructing an efficient and deadly dungeon, but about bum-rushing the domain of another dungeon keeper before he can do the same to you. This aberration might be acceptable, if the game clearly communicated to you that a dramatic change in tactics is needed. But instead of doing so, the introductory spiel actively misleads you into believing that this scenario should be approached the same way as the nine preceding ones. Even worse, if you fail to attack and kill the enemy quickly, he will soon make himself effectively invulnerable, leaving you stuck in a walking-dead situation; you can easily waste an hour or more before you realize it. Coming on the heels of so much good design, the scale of the design failure here is so enormous that I want to believe it’s some sort of technical mistake — surely nobody could have intended for the scenario to be like this, right? — but it’s hard for me to see how that could be the case either.

I did eventually figure out what the scenario wanted from me, but I was left feeling much the same as when I run into a really bad, unfair puzzle in an adventure game. At that point, the game has lost my trust, and it can never be regained. I played through a couple more scenarios — which, to be fair, returned to the old style that I had been enjoying — but somehow the magic was gone. I just wasn’t having fun anymore. So, I quit. Let this be a lesson to you, game designers: just like trust between two people in the real world, trust between a game and its player is slow and hard to build and terrifyingly quick and easy to destroy. For any of you readers who choose to play Dungeon Keeper — and there are still lots of good reasons to do so — I’d recommend that you go in forewarned and forearmed with a walkthrough or a cheat for the problem-child scenario.[2]When you hit the tenth scenario, you can skip over it by starting the game from the DOSBox command line with the additional parameter “/ level 11”.

The Dungeon Keeper story didn’t end with the original game. Late in 1997, Bullfrog and EA released a rather lazy expansion pack called The Deeper Dungeons, a collection of leftover scenarios that hadn’t made the cut the first time around, with no new campaign to connect them. Far more impressive is Dungeon Keeper 2, which arrived in the middle of 1999.

The team that made Dungeon Keeper 2 was mostly new, although a few old hands, among them programmer Jonty Barnes, did return to the fold. The lead designer this time was Sean Cooper, the father of Bullfrog’s earlier Syndicate. He remembers the project as “a shift from writing games without many plans to getting really organized about what we were going to build. It was about keeping everyone in full view of what we were all trying to do together. That’s common practice today, but it was one of the first times for us.”

Less an evolution of the first game’s systems than a straight-up remake with modernized graphics and interface, the sequel’s overall presentation is so improved that this doesn’t bother me a bit. What was murky and pixelated has become crisp and clear, without losing any of its malevolent style; Richard Riding has even returned to louche it up again as the velvet-tongued master of ceremonies. I only played about five scenarios into this 22-scenario campaign due to time pressures — being a digital antiquarian with a syllabus full of games to get through sometimes forces me to make hard choices about where I spend my supposed leisure time — but what I saw was an even better version of the first campaign. Plus, I’m given to understand that there are no aberrations here like the tenth scenario of that campaign. Some purists will tell you that the sequel lacks the first game’s “soul.” Personally, though, I’ll take the second game’s refinement over any such nebulous quality. If I was coming to Dungeon Keeper cold today, this is definitely where I would start.

But, whether due to a lack of soul or just because it was too much too soon of the same idiosyncratic concept, Dungeon Keeper 2 didn’t sell as well as its predecessor, and so the series ended here. Sadly, this was a running theme of Bullfrog’s post-Molyneux period, during which the games became more polished and conventionally “professional” but markedly less inventive, and didn’t always do that well in the marketplace either. “I felt the heart of the place was missing,” says Mark Healey. “Bullfrog was no longer a creative haven for me. It felt more like a chicken factory.” And the chickens kept laying eggs. Populous: The Beginning, the big game for 1998, disappointed commercially, as did Dungeon Keeper 2 the following year. The same year’s Theme Park World[3]in North America, Theme Park World was dubbed Sim Theme Park in a dubious attempt to conjoin Bullfrog’s legacy with that of Maxis of “Sim Everything” fame, another studio EA had recently scarfed up. did better, but had much of its thunder stolen by Rollercoaster Tycoon, an era-defining juggernaut which had been partially inspired by Bullfrog’s first Theme Park.

Early in 2000, EA closed Bullfrog’s Guildford offices, moving most of the staff into the mother ship’s sprawling new office complex in the London suburb of Chertsey, which lay only ten miles away. The Bullfrog brand was gradually phased out after that. Old games studios never die; they just fade away.

Setting Dungeon Keeper aside as a partial exception, I’ve made no secret of the fact that the actual artifacts of Bullfrog’s games have tended to strike me less positively than their modern reputation might suggest they should, that I consider the studio to have been better at blue-sky innovation than execution on the screen. Yet it cannot be denied that Bullfrog laid down a string of bold new templates that are still being followed today. So, credit where it’s due. Bullfrog’s place in gaming history is secure. It seems only fitting that Peter Molyneux have the last word on the studio that he co-founded and defined, whose ethic has to a large extent continued to guide him through his restlessly ambitious, controversy-fraught post-millennial career in games.

It [was] an amazing, joyful roller coaster which I wouldn’t have traded for anything. It was an obsession. We were just obsessed with doing stuff that other people hadn’t done before. It was working very late and very hard and smoking lots of cigarettes and eating lots of pizza and bringing together some crazy insane people. We just had the reason to do stuff. There wasn’t a lot of process involved. We didn’t have producers. There were some brutally tough times there, but it was amazing.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Bullfrog’s Official Guide to Dungeon Keeper by Melissa Tyler and Shin Kanaoya; PC Zone of May 1996 and May 2000; Retro Gamer 43, 71, 104, 110, 113, 130, 143, and 268; Computer Gaming World of December 1995, August 1997, October 1997, and October 1999; Computer Games Strategy Plus of November 1995.

Online sources include Peter Molyneux’s brief-lived personal blog, “Peter Molyneux: A fallen god of game design seeking one more chance” by Tom Phillips at EuroGamer, GameSpot’s vintage review of Dungeon Keeper, and “Legends of Game Design: Peter Molyneux” by Rob Dulin at the old GameSpot.

Where to Get Them: Theme Hospital, Dungeon Keeper Gold, and Dungeon Keeper 2 are all available as digital purchases at GOG.com.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Some details of the arrangement — namely, the financial side — remain unclear. Molyneux has claimed in a few places that he paid for the rest of Dungeon Keeper’s development out of his own pocket in addition to providing the office space, but he is not always a completely reliable witness about such things, and I haven’t seen this claim corroborated anywhere else. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | When you hit the tenth scenario, you can skip over it by starting the game from the DOSBox command line with the additional parameter “/ level 11”. |

| ↑3 | in North America, Theme Park World was dubbed Sim Theme Park in a dubious attempt to conjoin Bullfrog’s legacy with that of Maxis of “Sim Everything” fame, another studio EA had recently scarfed up. |