There’s lots of somethings to be said for sheer audacity in art, for a willingness to stick your neck out and give your audience something they never, ever expected from you. I think sometimes about how the first folks who listened to Revolver must have felt when the erstwhile cuddly Fab Four unleashed the otherworldly chaos of “Tomorrow Never Knows”; how the first buyers of Achtung, Baby must have felt when they hit the play button and heard not the expected soaring anthem but the grinding industrial murk of “Zoo Station”; how, to choose something I’ve already written a bit about here on this blog, viewers who tuned into The Prisoner‘s “Living in Harmony” episode must have felt when instead of a spy drama they got a Western that refused to reveal itself as a dream sequence but instead just kept going and going right through the show’s running time. Lots and lots of people run screaming from these sorts of switcheroos. As for me, though… they always send a thrill up my spine. A willingness to rip it up and start again is pretty high on the list of things likely to draw me to a creator.

I get some of that thrill when I think about those first people who booted up Ultima IV expecting to create a party via the usual min/maxing routine, only to be greeted with a simple story with the gravitas of a parable — a parable about, well, you.

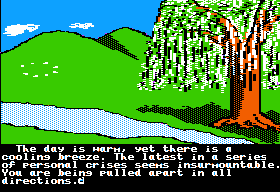

The day is warm, yet there is a cooling breeze. The latest in a series of personal crises seems insurmountable. You are being pulled apart in all directions.

Yet this afternoon walk in the countryside slowly brings relaxation to your harried mind. The soil and stain of modern high-tech living begins to wash off in layers. That willow tree near the stream looks comfortable and inviting.

The buzz of dragonflies and the whisper of the willow’s swaying branches bring a deep peace. Searching inward for tranquility and happiness, you close your eyes.

A high-pitched cascading sound like crystal wind chimes impinges on your floating awareness. As you open your eyes, you see a shimmering blueness rise from the ground. The sound seems to be emanating from this glowing portal.

There’s the echo of another spiritual journey’s beginning, that undertaken by the narrator of Dante’s Inferno: “In this the midway of our mortal life, I found me in a gloomy wood, astray, gone from the path direct.”

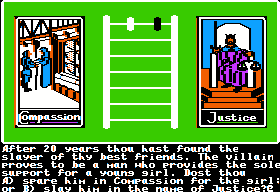

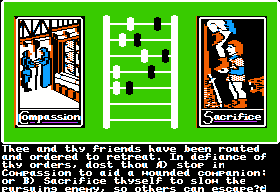

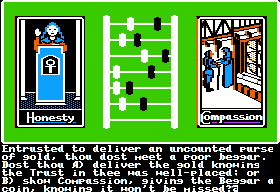

Ultima IV‘s opening parable culminates in a mysterious gypsy fortune teller who poses a series of ethical dilemmas designed to determine not what class or race you’d like to play but what kind of person you are. Of the eight noble virtues of Compassion, Honesty, Honor, Humility, Justice, Sacrifice, Spirituality, and Valor, which ones matter most to you?

By 1985 gaming had already seen its fair share of debates about who the player’s character in a role-playing game or interactive fiction really was. The very term “role-playing” would seem to imply that the player was not just playing herself thrust into another world, that she was playing a role there, performing as one of Gary Gygax’s idealized Shakespearian thespians. Infocom also had tried to sell their players, to decidedly mixed success and occasional howls of outrage, on seeing interactive fiction through the eyes of people who weren’t necessarily the same as them. For the grand experiment of Ultima IV to succeed it was critical that the opposite point of view prevail, that the player feel it to really be her in the game. Richard Garriott: “Since this is a game about the player’s personal virtues, it is very important that one always identifies with the character and feels responsible for the character’s deeds.”

In a computer game if you roll random dice, you’re just going to sit there and go roll, roll, roll. You get all maxed-out numbers and it’s, “Okay, I’ll take that one.” If you don’t let them roll out and you let them choose numbers, well, it’s kind of a fixed equation. Once they know the map and the game, they can make the perfect decision as to exactly what their stats should be if they are aware that the equations are internal. So I don’t want to give you either of those.

Ultima IV I wanted to be a very personal experience. The reason is because in most of these games you are the puppeteer running this puppet around the world. If this puppet is doing bad things it’s not you, it’s the puppet. You can detach. And I wanted this game to be about personal and social responsibility. It is very important that this be you in the world of Britannia, not something you’ve rolled up. If I’m the computer nerd at home wanting to be a big barbarian going around crushing things, I still want to be a computer nerd down there, in nice clothing. The essence of that character is really the essence of you as an individual.

The gypsy’s questions were designed to tease out the player’s real beliefs and place her in the role in the game that best suited her own personality — to whatever extent seven questions determining the most important to her of eight abstract virtues could manage such a feat, of course. Richard again:

We worked on the phrasing of those questions. Unfortunately, there’s no really perfect way to ask those questions that we’ve yet discovered. Here’s something else that’s interesting. When we were working on this system, I said, “Here’s what I want to do for character development.” I went around to everyone in the office, saying, “Here’s these eight virtues along with a short description as to what I mean by them. Give me your ranking, one to eight, as to how important you think they are.” And then about a week later, after we generated those questions, we went back to the same people and said, “Answer these questions.” Although our company was only about twenty people large, everybody except two people had the exact same outcome to the questions as they did to the judgment. And those two who were wrong only had two transposed in the list. And so it turns out you get the exact same responses as you do to an intellectual discussion of it.

For the record, every time I answer the questions Compassion trumps everything else, and thus I end up a bard starting just outside Lord British’s castle. I don’t know whether this necessarily represents the person I always am, but it’s certainly a good approximation of the person I’d most like to be. So, at least for me, the system does indeed seem to work pretty well.

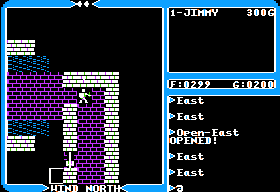

After that radical opening, the screen which greets the player after the gypsy has passed her final judgment must have struck many as comforting in its familiarity.

Yes, we’re back to our familiar view with our familiar alphabet soup of single-letter commands to explore the world. That world is now named Britannia rather than Sosaria; it was so renamed after Lord British united the land under his rule following the passing of the Three Ages of Darkness represented by Ultima I, II, and III. The fact that the geography is completely different from that of the previous game is similarly handwaved away, attributed to a great upheaval — must have been one hell of an upheaval — following the destruction of Exodus in Ultima III. The fact that Ultima II inexplicably took place on our Earth is, as per developing Ultima tradition, completely ignored; there are limits to what even the most dedicated ret-conner can accomplish. Also simply ignored is the last of the stupid attempts at anachronistic cleverness that dogged the early Ultimas, the big reveal at the end of Ultima III that Exodus was really a giant computer; in the Ultima IV manual’s version he was just your everyday world-domination-bent evil wizard.

Importantly, this new world of Britannia that you enter is not under attack from yet another evil wizard, or an evil anything else for that matter. This is one of the few CRPGs ever made, and almost certainly the first, to neither have an evil wizard nor to take place in some melodramatic Age of Darkness. Richard has drawn parallels between the Britannia of Ultima IV and Renaissance Italy — or, even better, King’s Arthur’s Britain at the height of the golden age of Camelot; between the player’s quest to become an Avatar of Virtue and the similarly spiritual quest for the Holy Grail. This quest is necessary not despite the land being peaceful and prosperous but because of it, because times of peace and prosperity are the only ones that allow the luxury of pondering a philosophy for living.

That said, becoming an Avatar of Virtue actually represents only the first step of the two-step process of solving Ultima IV. The second step requires you to descend into the Stygian Abyss, a remnant of the Dante-inspired Hell that was the centerpiece of Richard’s first conception for the game, and recover something called the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom. The final dungeon serves to hammer home the game’s rhetorical message via a series of puzzles which require you to apply what you’ve learned about the system of virtues, but everything that happens after you become an Avatar is otherwise much less interesting than what happens before. Just as what the Holy Grail represents to Lancelot is far more important to the legend than Galahad’s eventual drinking from it, the recovery of the physical Codex comes as something of an anticlimax to your achievement of Avatarhood. Richard Garriott himself said as much in later interviews, calling the Codex “largely irrelevant” to the real message of Ultima IV, even admitting that he had trouble remembering where or what the Codex actually was. Mostly it just allows Ultima IV a bit more of a traditional CRPG structure, serving as a stand-in for the usual evil wizard’s Whatchamacallit of Infinite Power that can be recovered only by defeating him at the bottom of the last and cruelest dungeon.

Let’s talk, then, about that first, more interesting stage of the game. Becoming an Avatar of Virtue requires that you demonstrate your dedication to each of the eight virtues through your deeds over many hours of adventuring in Britannia. When you have proved yourself worthy of “ascension” in a particular virtue, and have collected a necessary entry rune and a mantra, you can visit a shrine to that virtue and meditate to achieve one-eighth of your eventual Avatarhood. Ultima IV boldly applies these sorts of mystical trappings to an ethical philosophy which carefully avoids the subject of God in favor of simple practicality. Richard Garriott: “If I beat you up, you are going to be angry at me and will be on my back. If I’m nice to you, you are likely to be nice back. It makes good rational sense.” This has been expressed more rigorously by philosophers for millennia now as the idea of enlightened self-interest: you do best for yourself by doing well by others. Parsing a distinction which admittedly really exists only in his mind, Richard claims to ignore morals, which to him represent decisions about right and wrong based on feelings or spiritual beliefs, in favor of ethics, which are grounded in simple, rational common sense. A similar determination to remove the supernatural from the fantastic is everywhere in Ultima, perhaps as a byproduct of Richard being the son of a scientist who would probably have become one himself had Dungeons and Dragons and computers not stepped in. Richard saw Ultima IV‘s magic system, for instance, not as something mystical and mysterious but as merely the natural science of a world that just happens to have different natural laws than our own.

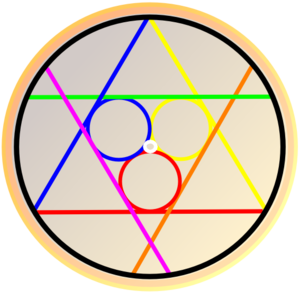

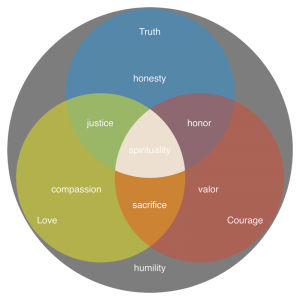

In developing Ultima IV‘s system of ethics, Richard began with a long jumble of possible virtues. Among them were three rather extreme abstractions on this list of abstractions: Truth, Love, and Courage. Watching The Wizard of Oz one day, it struck him that L. Frank Baum may have started with a similar list: “I thought of the Scarecrow looking for a brain, which was Truth; the Tin Man looking for a heart, Love; and the Cowardly Lion, looking for Courage.” It then occurred to his scientist’s mind that these three could be seen as core principles which could be combined to form most of the other items on his list. Honesty is Truth alone; Compassion is Love alone; Valor is Courage alone; Truth tempered by Love is Justice; Love and Courage are Sacrifice; Courage and Truth are Honor; Truth and Love and Courage all together become Spirituality; the absence of all three is Humility. Richard, who loved his symbols, devised a cool-looking diagram to represent the relationships, which ended up inadvertently — or at least subconsciously — resembling Judaism’s Star of David.

The symbol of Ultima IV’s system of virtues. The three traditional primary colors represent the core principles: blue is Truth, red Courage, yellow Love. They combine to form the eight virtues (including Humility, which contains none of the three and is thus the black border).

As a system of belief, it’s perhaps not exactly compelling for an adult (although, hey, cults have been founded on less). As an ethical philosophy… well, let’s just say that Richard Garriott is unlikely to ever rival Kant in university philosophy curricula. There are plenty of points to quibble about: Honesty, Compassion, and Valor are, at least in this formulation, really just synonyms for the core principles that supposedly compose them; the idea that Spirituality is made up of all the virtues lumped together seems kind of strange, as does its presence at all given Richard’s determinedly materialist worldview; the idea of Humility as literally an ethical vacuum seems truly bizarre. (Richard later clarified in interviews that he would have preferred this latter to be Pride, but, “Pride not being a virtue, we have to use Humility”; make of that what you will.) And of course the names of the virtues themselves are rather painfully redolent of the life of a Dungeons and Dragons-obsessed teenager. But poking holes in the system is really missing the point. Ultima IV gave its audience permission to think about these things, laid out in a cool if only superficially logical way. The fact that these ethics still speak the language of Dungeons and Dragons was a good thing, because that’s the language most of Ultima IV‘s audience spoke. Richard himself didn’t claim any mystical truth for the system, freely admitting in interviews that it was essentially arbitrary, that dozens of other formulations could have served his purposes just as well. The one real overriding concern I have with the system is that it can lead to a possibly dangerous ethical absolutism; the only place where Ultima IV does even lip service to the idea that there can be conflicts between its virtues, debate about their merits, is in those questions that open the game. (To his credit, Richard Garriott also spotted the danger, and, indeed, dedicated Ultima V, in many ways an even more thoughtful work than its more heralded predecessor, to exploring the danger of ethical absolutism. Richard characterized that game as, “Now that you’ve shown everybody Avatarhood, let’s show everybody why it’s bad.”)

The way that you build (or lose) mastery of the various virtues is by far the most interesting mechanic in the game, the core thing that makes Ultima IV Ultima IV and the core reason for the game’s stellar reputation today. As you go about your business in its world, Ultima IV is quietly monitoring your actions. If you cheat the blind magic-store proprietor by sneakily paying her less than you should, you lose Honesty; if you’re square with her, you gain it. Running away from enemies costs you Valor; standing and fighting gains it. Giving blood to the healer gains you Sacrifice; refusing costs it. Giving money to beggars gains you Compassion; refusing them… well, you get the picture. Unsurprisingly, the idea has its roots in an admittedly not-widely-used rule in Dungeons and Dragons, which recommends that Dungeon Masters monitor and chart the actions of their players in relation to their professed alignment — “lawful evil,” “chaotic good,” etc. Drift enough and the Dungeon Master could actually impose a new alignment on you, possibly with drastic consequences if, say, your god demanded a certain alignment. In Ultima IV, your progress in the virtues is, inevitably, nothing more than a system of numerical attributes not fundamentally unlike other character attributes — Strength, Experience, Gold, etc. Still, just as Ultima IV tries to make character creation more than a series of dice rolls, it strains mightily to make the virtues an honest reflection of your attitudes and behaviors rather than just a system to be optimized. It hides all of the numbers from you. The only way to learn of your progress in the virtues is to visit the Seer Hawkwind in Lord British’s castle, and even then he just describes your progress in vague generalities. Especially in this day and age, when all of the virtue system’s mechanics have been meticulously documented, we understand all too well that it’s possible to, say, raise Compassion to Avatar level just by giving over and over to the same beggar in the same town. But back in the day particularly, when the system’s underpinnings were not so well understood, it really did feel organic.

The other mechanics of solving Ultima IV — the minutiae of classes and equipment and monsters and leveling up, the puzzles and quests and how to solve them, the locations of towns and dungeons and shrines and artifacts, the seven companions (each representing one of the seven virtues you didn’t choose as most important to you at the beginning of the game) you must eventually round up to complete your adventuring party, etc., etc. — have likewise already been documented as extensively as those of any videogame ever produced. In addition to the countless FAQs, blogs, and web sites generated by the franchise’s many still-rabid fans, at least half a dozen entire books have been published with detailed descriptions of exactly how to best play and solve the game. Most of the nuts and bolts of Ultima IV‘s engine merely extend the technology that Richard had already built through Ultima III in fairly commonsense ways; Richard has often stated that Akalabeth through Ultima III were mostly about improving his technology, Ultima IV about applying his technology at long last to a really worthwhile design. So, I’m not going to talk about most of that in a great deal of depth here; there’s little or nothing I could add to the mountain of practical data at every web surfer’s fingertips, and few fundamental changes to note in the mechanics I described in earlier articles about the franchise. You’ve got a (larger) world map to traverse along with cities, towns, castles, and dungeons; you’ve got horses, ships, and other vehicles to acquire; you’ve got food and equipment to manage (along with, this time, spell reagents, and for a party that will eventually number eight rather than the four of Ultima III); you’ve got lots of people to talk to (this time with a keyword-based pseudo-parser to deepen the interactive possibilities); and of course you’ve got monsters to fight. By now you know the drill.

At this point I probably should confess something: I’m far from sold on Ultima IV as a holistic, playable game. Oh, the concept of the virtues that overlays and underlies the whole is as brilliant and inspiring as I and so many others have already said it is. But you don’t spend all that large a percentage of your time in Ultima IV directly engaging with that concept. You rather spend a whole lot of time, easily hundreds of hours worth if you play the game “straight,” without walkthroughs or spoilers, on lots of things that are often less than compelling at best, dull at average, horrifically, unfairly cruel at worst. Take (please!) the much-vaunted new magic system, in which you have to prepare every single spell you cast by buying its reagents and mixing them together one at a time, a process absolutely devoid of interest after you figure out a given spell’s recipe, one that entails about half a dozen key presses for every single spell you prepare; you can easily spend ten minutes just getting the spells ready for a major dungeon expedition. Combat, never a strong point for Ultima, is more infuriating here than ever; you now have to micromanage up to eight characters through the busywork of taking out the endless hordes of uninteresting monsters that constantly attack when you just want to, you know, walk to the next damn town already. (The number of monsters in each attacking group is actually keyed to the number of characters in your party. In an interesting example of unintended consequences, this means that just about all guides to the game recommend keeping to a party of one as long as possible to try to stave off some of the soul-killing boredom of combat for as long as possible.)

Ultima IV itself doesn’t do a very good job of evincing virtues like Compassion, Justice, even Honor. This is a staggeringly difficult game, a fact that gets rather obscured by the fact that most people playing the game and/or writing about it today are mostly replaying it, and usually with the benefit of that aforementioned copious store of FAQs and walkthroughs. Taken without all that, the way a kid who found it under the tree at Christmas 1985 would have had to approach it, it’s honestly hard to imagine anyone solving it unaided. The design is a spiderweb of all but invisible strands; fail to trace any one of them and you won’t win. Most of the cities in the game are marked on the cloth map that came in the package, but just enough are left unmarked that you’ll need to scour the whole map square by tedious square to find everything. One village sits at the center of a huge inland lake, its existence impossible to detect unless you happen to meet a pirate ship on the lake — a vanishingly unusual occurrence — fight it, steal it, and take it for a sail. Or you can find the village if you manifest an apparent death wish and sail a ship on the open ocean directly into a whirlpool. Many of the towns and castles contain critical secret doors that are distinguished by the presence of one extra pixel amidst the grainy graphics.

See that single white dot above the character that looks kind of like a graphics artifact of some sort? That’s a game-critical secret door.

Conversations can be another nightmare. Every character in the game responds to three keywords given in the manual: “Name,” “Job,” and “Health” (no, I don’t know how Richard settled on that particular inexplicable trio). You’re expected to find other keywords by asking about things the character mentions in those three generic openers, in addition to following up on clues gained in other places of the “Ask XX about YY” variety. But, inevitably, the vast majority of promising-looking words any character mentions are actually not keywords at all. Conversations quickly devolve into a rote entering of every noun or active verb a character uses, with 90 percent of them resulting in “That, I cannot help thee with.” Miss one critical word in a conversation out of sloth or negligence, and that’s a clue overlooked, a thread untraced, and your chance for victory undone. Each town or castle, which number sixteen in total, is populated with dozens of individuals. Miss that critical fellow hiding out in a visually impenetrable glade at the extreme edge of the map, and you’re screwed. Miss the single pixel representing a secret door, and you’re screwed. When you finally get to the very bottom of the Stygian Abyss and stand before the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom, if you fail to answer correctly an out-of-left-field question whose answer requires the ability to read Richard Garriott’s mind, you’re screwed — teleported back to the surface to battle your way down through eight levels of the fiercest creatures in the game and try again. If you were playing in 1985, without the benefit of emulator save states, you would get to do this again and again until you gave up or, as many people finally did, called Origin’s hint line for the answer. If none of what I’ve just described sounds like all that much fun, that’s because for all but the most dogged of players of today it’s really not. Like so many old-school adventure designs, it rewards not cleverness but sheer persistence, a willingness to lawnmower through map after conversation after battle no matter how boring it is.

That, then, is the flip side to Ultima IV the transcendent masterwork: Ultima IV the fiddly, borderline unplayable, tedious mishmash. It’s absurdly easy to make any adventure game impossible, which is one of the many reasons that a designer needs playtesters, and lots of them. Richard Garriott, however, had basically no feedback on many parts of his design. In an interview for Computer Gaming World published shortly after the game, he let drop the bombshell that he was the only person who had managed to complete the game when Origin put it in a box and unleashed it on the world.

A few years ago Michael Abbott, academic and “Brainy Gamer,” sparked quite some conversation with a blog post telling how his students had rejected Ultima IV as “boring.” Predictable outrage toward those kids today followed in the comments and the heaps of reaction posts from other bloggers. Yet my own reaction is to side with Dr. Abbott’s students; Ultima IV is, most of the time, pretty boring. Good on them for recognizing this, I say, for refusing to get sucked into doing boring things for the sake of it. I think kids today are at a minimum every bit as smart as those of my generation were when Ultima IV first hit store shelves, thoroughly capable of deciding that a game is mostly just wasting their time. We shouldn’t begrudge them that freedom if more refined entertainments make their verdict an uncomfortable one for us. Ultima IV stands for me as a hugely important work in the history of its medium, but also one that hasn’t stood the test of time all that well. I love to think about it, love the fact that it exists, that Richard Garriott had the courage to make it — but just thinking about playing it makes me tired. Like a work of conceptual art, to some extent the real power of Ultima IV today is just the fact of its existence.

Of course I’m well aware as a digital historian that my modern take on Ultima IV is a fundamentally anachronistic one. In 1985, the game represented an all but unrivaled gateway to imagination. Solving an Ultima wasn’t really the point; these were worlds to explore, to revisit over a period of months or years until the next Ultima came out (Ultima V would be almost three years in arriving). Everything about Ultima IV — packaged in its big, grandiose box with two big, ornate manuals, with its die-cast ankh that countless boys stuck on a chain and wore to school around their necks, with its big cloth map — marked it as something special, something to be cherished and savored.

The ankh would join the Silver Serpent as one of the enduring symbols of Ultima, a supposed visual representation of the Way of the Avatar to stand alongside the diagram of the virtues. It was yet another bit of pop-culture detritus that made its way into Ultima: Richard first saw it in the movie Logan’s Run, where it served as the symbol of an underground resistance movement, thought it looked cool and “positive,” and stuck it in the game. When he learned that it meant “life and rebirth” to ancient Egyptians, that just made it that much cooler.

When you discovered a new village tucked away in some corner of the map you didn’t complain about the unfairness of it all, you rejoiced at having uncovered another corner of this fantastic world. Actually solving the game was something that few managed, but it didn’t really matter that much anyway. The point was the journey. Even the price contributed: showing an instinct for manipulating perception through pricing that would have done Apple proud, Origin’s suggested list price gave the game a street price of $50 to $55, about $20 more than the typical title. Far from cutting into its sales, the high price just made the game all the more desirable, all the more special. This experience of Ultima IV was absolutely specific to its time and place, not something we can recapture today no matter how much we blog or commentate or notate. Yes, the magic of Ultima IV was ephemeral, but in its day it was very, very powerful.

By way of illustration, let me tell you about Brian. Brian was one of my best friends in middle and high school, his attitudes fairly typical of the cracking and pirating underground in which he was quite thoroughly immersed. Like most of his friends in the scene, Brian didn’t so much play games as collect them. He had hundreds, maybe thousands of Commodore 64 floppies containing virtually every remotely notable game released for the platform in North America or Europe. Most got booted once or twice, to see what the graphics were like; a few action games would grab his attention in a bigger way for a while, but were soon set aside in favor of haunting the pirate BBS network and enjoying the social dramas of the cracking scene (let me tell you, teenage girls had nothing on this crew). Ultima IV, though, was different. It’s the only game I can ever remember Brian actually buying, the only one more complicated than Boulderdash for which he read the manual, into which he put a real effort. Like a hundred thousand other kids, he hung the map on his bedroom wall, wore the ankh to school. Oh, I’m pretty sure he never came close to finishing it. He probably played it much less, all told, than most similar kids who didn’t have the same embarrassment of gaming riches from which to choose. But the fact that his teenage heavy-metal nihilism went away when he talked about the virtues, that it awoke some other — better? — part of him that was impervious to every other game… I’ve always remembered that. Ultima, and Ultima IV in particular, was just like that.

Chester Bolingbroke, better known as the CRPG Addict, was another Brian.

I wrote each [virtue] with its definition on an index card and every morning I shuffled the cards and chose one at random. That one, I did my best to practice for the day. If honesty came up, I was careful to tell no lies throughout the day. If it was sacrifice, I looked for ways to do something charitable.

Not many, I suspect, would admit to deriving what amounts to their religion from a computer game. But I had rejected conventional religion even as a pre-teen. I balked at Judeo-Christian doctrines that seemed both haphazard and arbitrary: meticulous rules about food and dress, but none about the need to actively seek out and destroy evil (my interpretation of “valor”); commandments against adultery and sabbath-breaking, but none against assault and slavery. Ultima IV, on the other hand, offered a comprehensive and completely nondenominational — secular, even — system of virtue. It fit me like a glove.

There were hundreds of thousands of kids just like Brian and Chester. Ultima IV caused its players to set aside their angst and their irony and try to improve themselves in school lunch rooms and family dinner tables across the land. It was far from the first game with artistic aspirations, far from the first to want to be about something more than escapism; 1985 alone also brought Mindwheel, A Mind Forever Voyaging, and Balance of Power. But those admittedly more philosophically sophisticated efforts appealed mostly to a different, older audience; the average age of the average Infocom buyer was north of thirty, while very few kids indeed had the wherewithal to corner a Macintosh long enough to play Balance of Power even had they been interested in the vagaries of geopolitics. Part of the magic of Ultima IV was that it had been created by a kid just like the ones who mostly played it, raised on Dungeons and Dragons and Star Wars, more comfortable with a movie than a novel. Richard Garriott spoke their language, came from the same place they were coming from. Ultima IV, the last of the one-man-band Ultimas, still stands as the most personal expression he would ever create. When he said that ethics matter, that we have the power to choose our values and to live according to them, it resonated because it reflected, as art should, his own lived experience. Yes, many of its players would outgrow Ultima IV‘s simplistic take on ethics, just as many would outgrow the game itself. But hopefully few of that small minority who completed it ever forgot its closing exhortation, delivered as it was in Richard Garriott’s best teenage-Dungeon-Master diction:

Thou must know that the quest to become an Avatar is the endless quest of a lifetime. Avatarhood is a living gift. It must always and forever be nurtured to flourish. For if thou dost stray from the paths of virtue, thy way may be lost forever. Return now unto thine own world. Live there as an example to thy people, as our memory of thy gallant deeds serves us.

(You can download Ultima IV for free from GOG.com. Sources for this article are the same as for the last. I borrowed the diagram of the virtues from Eliott Wall.)

Lindsey Simon

July 11, 2014 at 5:37 pm

I spent SO much time playing Ultima IV as a kid. The depth of imagination and my connection to the game were really profound. It was unlike any game I ever played, and yes it was often infuriating. But it was also rewarding. Did you ever try turning one of the floppies upside down and playing? That was like magic. I’m 40 now and I still remember my first fireball from the fireball wand. The begging slaves, trying to get my boat to land on the square where the whirlpool was. It was haunting, and amazing.

MD

May 20, 2022 at 3:22 am

What was it with that damn whirlpool? I have memories of frustration trying to figure out how to get in it!

Jason Dyer

July 11, 2014 at 5:51 pm

Just for fun I tried the test myself (giving the answers I would give rather than shooting for a particular class). Ended up with Honesty/Mage. (I didn’t have the Honesty – Compassion shootout like your screenshot, though; might’ve gone for compassion on that one.)

Jason Dyer

July 11, 2014 at 5:56 pm

Oh, I should also point out Ultima IV by itself can be had from GOG.com for free:

http://www.gog.com/game/ultima_4

Jimmy Maher

July 12, 2014 at 7:33 am

I didn’t realize that. Updated the link at the end of the article to point to the free version. Thanks!

matt w

July 11, 2014 at 6:23 pm

I’m glad to read your assessment of the gameplay; I picked it up from GOG and while I kind of like scouring the villages (it doesn’t take that long to pick up on where Garriott likes to hide stuff) I have grown to hate poison traps with a passion. Seems like you need gold to progress… but opening a chest gives you a random chance of a trap that doesn’t even have the decency to kill you outright but sends you on a most likely futile foot slog back to the nearest healer, if you even know where that is. You could take care of this by stocking up on heal spells… if most towns had herb shops. How can towns not have herb shops? After a TPK entirely due to poison traps I had some choice words for Lord British but he wast unable to help me with any of them.

I got Tinker/Sacrifice which seems kind of odd.

There is a scenario where the virtues do seem to conflict — it seems as though you can gain some virtue (sacrifice?) by being the last one to run away, though presumably you lose valor for it.

By the way the phrase “enlightened self-interest” seems to come from de Tocqueville, though the expression of the thought perhaps goes back at least to the argument in the Apology that no man would willingly make his neighbors worse.

Jimmy Maher

July 12, 2014 at 8:44 am

I think the tinker is actually one of the better characters to start with from a purely min/maxing point of view, so there’s that…

I would draw a distinction between virtues that conflict intentionally to make rhetorical points and those that perhaps conflict due to an accident of mechanics. I think the few conflicts you’ll find in Ultima IV are more examples of the latter.

Andrew Schultz

July 23, 2014 at 2:39 pm

Mages 4 Eva!

There’s one super powerful item you can get that sends things out of whack. Information is power in the game–when I replay it once a year, I know how to start quickly, so I can get up to level 8.

One ironic thing about choosing a mage is that I am probably dishonest in my starting class choices in order to choose the honesty class.

Hattyfatner

February 22, 2019 at 4:26 pm

If you get poisoned you can cast Cure by mixing ginseng and garlic which you start some of each.

Andrew Plotkin

July 11, 2014 at 6:35 pm

I played the thing, back in the day, and I solved it up to that last one-word riddle. Failed at that twice, gave up.

But I don’t remember the game as *hard*. Hard is the wrong word. It was an exercise in detail-oriented patience. You *can* see that extra pixel if you look for it *every time*, and if you don’t — well, you’re playing the wrong game. Similarly, every NPC has something to tell you, and you plumb their stupid conversation keywords until you find it. If you haven’t seen the other side of a lake or mountain range, you’re not done with it. And so on.

Tedious, yes. In all the ways you cite above and more. Not *hard*.

On the other hand, my reaction to the virtue system was essentially the same as my reaction today. “Clever idea, props for trying, but this is a set of simplistic game mechanics for me to exploit.”

Jimmy Maher

July 12, 2014 at 8:50 am

Horse for courses, I suppose. :) I would more characterize Ultima IV as “hard, but for all the wrong reasons.”

I’ve just learned from a private email, by the way, that the answer to the final riddle was supposed to have been given — or at least strongly hinted at — by Smith the talking horse in Paws. But Richard forgot to put it in in the rushed run-up to release, and since, as I noted in the article, much of the game was never really tested *at all*… well, mark it down as yet another example of the need for play-testing.

Dehumanizer

July 12, 2014 at 11:06 am

Which is why they made it a running gag in the sequels, where Smith always gives a vital clue for the previous game. :)

Andrew Schultz

July 23, 2014 at 2:42 pm

I remember seeing this in Ultima V and thinking “Gee, thanks for saying it now. Maybe I’ll get around to it…”

…and then getting absorbed in U5.

Of course, years later, when I sat down to replay, I roughly remembered how everything was done, I looked for the animal that gave you the clue for the final puzzle in Ultima 4, wondering where it could be. Cove? Vesper?

cim

December 31, 2014 at 5:01 pm

There was another clue to it – when you successfully meditate to get an eighth at a shrine, you see a vision of a rune. Translating the runes gives you the answer to the final riddle. (And there is someone in one of the towns who hints that all eight virtues combined makes “one”, too)

So I had the answer well ahead of time, and kept asking people in towns about it to no avail. It was somewhat of an anti-climax when the time came to finally use it.

Not impossible to work out in-game, but certainly by far one of the more severe of the “you have to pay attention to absolutely everything” moments.

Anyway, a fascinating pair of articles – thanks for writing them.

jrodman

June 22, 2015 at 6:35 am

When I played this on the C64 in 1987 or so, I figured out the answer to the final puzzle based on information in the game. There are several things that point to it, even though the answer is, to me, still less than satisfying.

Playing it again a year ago or so from the GOG.com version (which I believe is a PC release), there was a very strong indication of the answer in Cove.

Alex Smith

July 11, 2014 at 6:56 pm

Your Ultima IV posts are some of your best work so (which is a high compliment considering your work is uniformly excellent). Truly interesting to peel away the layers of Garriott’s canned interview responses to arrive at the true inspirations for the game.

One small typo. Unless there are more drugs involved in becoming the Avatar than I remember, we should “meditate” at the shrines rather than “medicate.”

Jimmy Maher

July 12, 2014 at 8:51 am

:) Thanks!

Mike Taylor

March 27, 2018 at 12:44 am

When typos become art :-)

matt w

July 11, 2014 at 6:56 pm

I did have an experience with my personal virtuous code. I bugged Vorpal the prisoner too much and he attacked me, so I ran away without fighting — because even if he’s a bad guy you’re not allowed to kill prisoners. Then he was gone from the map. I suspect I took some hits on the virtues for that but I still think I did the right thing.

Andrew Schultz

July 23, 2014 at 2:46 pm

In case you’re wondering, the game doesn’t subtract for enemies who attack you. It gives you compassion if you don’t kill a fleeing serpent or other non-evil animals in combat.

I don’t think you lose virtues for fleeing from non-evil enemies, but I don’t know if the prisoner qualifies. The game’s a bit vague, and it’s really frustrating to be in a moral dilemma in a town after you’re unable to save a while.

You’re right, though. Attacking in a town loses all kinds of virtues. Even someone about to attack you. And especially that stupid mage in the Jhelom towers who can outright block your path to find an important item.

Victor Gijsbers

July 11, 2014 at 9:32 pm

Another great article. But let me take issue with this:

“It’s just the Golden Rule we all learned in kindergarten, which has been expressed more rigorously by philosophers for millennia now as the idea of enlightened self-interest: you do best for yourself by doing well by others.”

I really don’t think that counselling people to pursue their enlightened self-interest by being nice to others is a more rigorous way of stating the Golden Rule. If the Golden Rule is to be taken as a serious ethical principle, than surely it should be unconditional. Treat others as you would like them to treat you — regardless of whether this will bring you gain! If you know you can mistreat someone without consequences, or gain something by mistreating people, you still should not do that.

If I treat you well because I assume that this will bring me personal gain, I am in fact breaking Kant’s central moral principle: “Do not treat other people merely as means to ends.”

Jimmy Maher

July 12, 2014 at 8:56 am

And that’s why it’s good to have at least a couple of you professional philosophers reading this blog. :) You’re right, of course. Edit made.

Wade

July 12, 2014 at 1:54 pm

Kant never had a computer game yelling “THOU HAST LOST AN EIGHTH!” at him.

nik

July 12, 2014 at 3:49 am

Thanks for that article. I remember 13 year old me playing this game way back when, and I remember exactly how it felt – I was kind of thrilled the game would allow me to make my own moral choices and guide me along that path.

As I recall it the game seemed to encourage one to “act as if it were you in real life” though. That’s what I did. And then I found it kind of disappointing that that was not what was required to complete the game.

I had a choice to make: Either stick with my own decisions as I would make them in any given situation in the game. Essentially the choice to stay true to myself. Or do what the game wants you to do to collect all the virtues and become an avatar.

My choice was to stay true to myself of course, as the game encouraged one to do. I gave up on becoming an avatar and continued running around in the world for a bit longer before getting bored.

The fact that a game compels a teenager to make that kind of choice is in itself amazing. Legendary, even if I never even came close to finishing it. Reading the above, I am actually glad I never tried, there’s no way I’d have been able to.

Jimmy Maher

July 12, 2014 at 8:57 am

That’s a really interesting take on the game, one I don’t think I’ve seen before.

Al-Khwarizmi

July 12, 2014 at 9:11 am

While I agree the game is really hard by modern standards, it wasn’t that hard in its context. It was on the level of other contemporary CRPG’s like the Might & Magic series. I finished it when I was a kid (and a non-native English speaker) with almost no spoilers.

The secret door pixel actually stuck out like a sore thumb once you had figured out what it meant. Your sight was trained to spot it so it became as obvious as if the wall had been colored bright pink. The combat wasn’t so boring if you had time, and I have fond memories of cool naval battles. The “name, health, job” thing I figured out soon, and if a 10 or 12-year-old kid with mediocre English could, any player worth their name can. After all, the game prompt was asking you something equivalent “What would you like to ask about?” and those are standard things you would ask a stranger about, it’s a quite common-sense thing. Just not fitting the current standards where there are tutorials for everything.

The reagent mixing… yes, that *was* very boring. If a remake were done today, I’d ask for better graphics and a better UI for that, the rest I would leave as it is.

Joel Webber

July 12, 2014 at 1:59 pm

I think this is a pretty accurate take on the difficulty of Ultima IV. It was a long, hard slog, full of details that you couldn’t miss. It also required that you take copious notes, and do a fair amount of mapping, as was not uncommon for games of the time, but almost unheard of today.

I remember playing the game for many months (probably pushing a year, on and off) when I was a kid, and did eventually finish it. At the time, I think I just assumed that I was slower than other gamers — I had no idea it was rare for people to actually finish the game. I also have no idea how I figured out the answer to the last question — IIRC, I played through the Abyss several times before guessing it, which seems implausible now, but I must have, because I didn’t know anyone else who could have given it to me.

Looking back, I find myself incredibly nostalgic for the time when games required this much investment of time and effort — especially all the note-taking, map-making, and thinking-about-puzzles-until-4am. Even as my adult self could never imagine finding enough free time to make it through such a game. But I suspect that’s a style that’s now firmly in the past.

matt w

July 15, 2014 at 5:22 pm

Actually “name, health, job” is in the manual (at least, the one that they included with the GOG version).

Adam Huemer

June 20, 2025 at 2:11 pm

Might & Magic is pretty easy compared to The Bard’s Tale or Wizardry.

Thomas Prewitt

July 12, 2014 at 9:25 pm

You claim “There were hundreds of thousands of kids just like Brian and Chester. Ultima IV caused its players to set aside their angst and their irony and try to improve themselves in school lunch rooms and family dinner tables across the land.”

Really now? You believe hundreds of thousands of kids tried to improve themselves because of this?

Jimmy Maher

July 13, 2014 at 7:10 am

Yes.

DZ-Jay

March 2, 2017 at 5:56 pm

In spite of not having played the game myself, but having experienced first hand the deep influence an ostensibly deep(-ish) philosophical point of view can have on the impressionable mind of a young teenager full of angst and eager to shape his own world (whether picked up from a pulp book, a movie, a video game, a song, or anything else); I will definitely agree with Jimmy — without a hint of irony or cheek.

Now, whether these influences are strong enough to persist through life, or for that matter, throughout a particular summer, is debatable. However, that’s a separate question altogether.

dZ.

KenHR

July 14, 2014 at 12:51 am

Great entry yet again.

I remember playing this in my teens and being really impressed by the moral/ethical slant of the game. I never really played it to win, though; I just enjoyed exploring the world more than trying to fulfill the quest.

Gilles Duchesne

July 14, 2014 at 6:25 pm

One thing that hasn’t been mentioned yet is how, in those pre-internet days, knowledge about the game would get shared among gamers.

I remember how, along with (cough cough) copied disks and photocopied cloth maps, I also got my hands on very thorough dungeon maps, documents (like a virtue/companion/town/color/rune/mantra table) and notes.

So even though searching for “that hidden NPC” or for some obscure hidden passage was tedious in itself, it became part of this meta-game of sorts, where discovering a clue – any clue – would be proudly share with several other players. I guess that could also be said about many adventure games, but Ultima IV is certainly one where I personally experience it.

Nonetheless, the tedium did get to me. After spending an entire evening looking for the “Wheel of the HMS Cape”, an heartquake made us lose power right as I found it. After that, I pretty much gave up.

Gilles Duchesne

July 14, 2014 at 7:47 pm

Another anecdote I just remembered: around the same time I played, in high school, we had a class on the 8 Beatitudes (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beatitudes), and I remember how I tried connecting them to the 8 Virtues.

(Yes, some of them require a bit of a stretch, but then again, hardly worse than the kind of creative thinking Mr. Garriott was known for back then.)

Iggy Drougge

July 15, 2014 at 1:50 am

Reading the previous installments about Ultima, I was thinking Garriot was just a stupid kid. Ultima IV makes him seem more like an idiot savant.

Hitfan

July 16, 2014 at 1:55 am

Great article. But I have one caveat: in most modern reviews and retrospectives of Ultima IV, there is barely a mention of the music that plays throughout the game. The music provides atmosphere and dramatic tension.

The freeware download of U4 plays in DOS, and plays no music at all. (At least by default).

I’d recommend that newcomers seek out the Commodore 64 version just to see the difference.

Jimmy Maher

July 16, 2014 at 6:47 am

Yes, good point. The music — the only substantial thing in the game that Richard *didn’t* do himself — is very impressive, and does add a lot to the atmosphere, although I must confess that even it does become grating for me, and I always turn it off after an hour or two. (But I’m not a big background music person; I’m an active listener, so if I really like something I want to just, you know, sit and listen to it.) Since the music is impressive but not necessarily *more* impressive than that of Ultima III, I just lumped it into “ways in which Ultima IV is technologically very similar to Ultima III.”

But yeah, that’s one more part of the original Ultima experience that someone who downloads the game from Gog.com today and dives in is missing.

Dehumanizer

July 16, 2014 at 2:25 pm

There are patches for Ultimas 3 to 5 adding MIDI music (converted from the C64 / Apple II versions, I guess) to the DOS versions. The games certainly become a lot more playable with them.

Links (on the Ultima wiki): Ultima III Ultima IV Ultima V. A patch for Ultima II also exists, adding EGA graphics, but not music (since the game doesn’t have any).

RushJet1

September 17, 2014 at 12:27 pm

I made a Famicom cover of the dungeon theme from this game if you’re interested… actually two, the first is really close to the original and the second one adds 2 tracks.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U1Z-KOOCWrk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m9DhD-w2Fq8

Hitfan

July 16, 2014 at 2:04 am

U4 was the very first computer RPG I ever played. I was so inspired by it, that me and a friend in high school attempted to make our own computer RPGs. We spent many of our after-school afternoons trying to accomplish this.

Recently, I did revisit the 25+ year old code of these previous endeavours and finally assembled a fully working CRPG from all those disjointed pieces like Brian Wilson did decades after the original ambitious SMiLE sessions were recorded and abandoned.

You can read more about it here:

Ultimate Quest

Ron Newcomb

July 20, 2014 at 4:12 pm

I remember playing this to completion, but I played the NES version, which was far more playable than any PC version. Also had good music. I remember I kept getting the Bard for my character class but wanting a Ranger.

I remember the Venn diagram of virtues as cute and it’s application by a videogame as really interesting, but I never took it out into the real world anymore than I did Dungeons & Dragon’s alignment system.

I don’t know how many things are different in the NES version, but the game there played a lot like typical NES games of the time, so I imagine it’s pretty different.

Andrew Schultz

July 23, 2014 at 2:37 pm

I remember getting into an argument with the frenemy who showed me U4 on his Commodore over one conversation. One person asks if you are the avatar. I figured I didn’t want to lose an eighth in Honesty, so, yes.

“Thou has lost an eighth!” Bye bye, humility.

At the time I had no clue how far this would make me fall (hint: not very) but I hadn’t saved the game for a while, I didn’t want to visit that shrine, and I got mad.

That said, I love how the game blends the principles, and even though I now know Garriott didn’t see it as hard and fast moral advice, it still feels right and useful to me.

Keith Armonaitis

July 28, 2014 at 4:51 am

I remember well when I picked up Ultima IV back in the day. Ultima I had taken me a couple of months to finish, II a month, III I remember finishing in a little over a week. I remember thinking if IV didn’t take me longer I was’t buying anymore of his games. I actually thought that I knew how Garriott thought – boy was I wrong.

The fact that IV took me a couple of months to complete is no small feat. Somewhere I probably still have all of my notes from that game, the maps, the clues given in game, everything. I was meticulous and probably a little OCD about game playing back then. But I did get through it, and it pretty much cured me off of Ultima after that. Until Ultima Online broke my heart of course, but that is a tale for another day.

PS- And thanks for all of the great articles. Of course I am getting nothing done since I have been reading your site, but it has been a fantastic trip down memory lane. How you have the ability to be so prolific with your articles with so much that has to be researched astounds me. Keep up the great work.

Brandon Campbell

November 9, 2014 at 1:39 pm

I have desperately wanted and tried to like this game and some of the other Ultimas, but so far haven’t had the patience for exactly all the reasons you have explained so well in this article.

Nathaniel Olsson

February 5, 2015 at 10:06 pm

I loved the game as a teen very similar to “Brian” in the article. I never finished Ultima IV until I played as an adult. The Exult simulator makes many of the annoying spell mixing and other interface quirks more tolerable, and with it I have been able to finish the game in under 10,000 turns. I have seen a number of speedruns on YouTube, but nowhere have I seen anyone crowing about finishing in the fewest turns (as opposed to fastest time), so I’ve just done it here. ;-)

Nathaniel Olsson

February 7, 2015 at 6:19 am

Correction: Exult is a simulator for Ultima 7. xu4 is the humbler Ultima IV simulator that improves the gameplay and limits the frustration quite a bit.

Steven Bishop

May 3, 2015 at 11:08 am

I championed Ultima IV again recently as a sort of reconnect with my youthful passion. I decided to play Shepherd. I love the story opening, being transported into the immediate world of mystery on the barren island of Magincia, discovering the ruin, feeling the rush of seeing the living daemon, and reestablishing contact with the moon gate.

This time around I noticed saving for magic weapons was no where near as important to me. As a kid, I remember suiting everyone up and arming to the hilt, only to sell off everything for max gems, ingredients and food for the Abyss.

Now it was more about preparing my fellows with as much dexterity I could find. Intellegence second, Strength not as important in my maturity.

I never, I mean ever, got into flaming oils? And I planned heavily this time for two characters to wield halberds, but they just always seem to miss!

When I was a kid, I was so engulfed in this game. My father bought me an Apple II C. I was 11 carting that around to sleepovers. LOL. Dad wanted me to learn programming, but I had to save the world first! I always named my character British, because Lord British was a sort of my alternative dad.

Phil Fortier

October 3, 2015 at 6:27 am

Just ran across this article, good read. Admittedly, I find these old games are never quite as fun as they were when I was a kid – I guess I remember them through rose-tinted glasses.

But I find a few of your complaints strange; in the sense that you’re complaining about elements of the game that I really enjoyed. I probably had a lot more patience back then than I do now :-)

“Most of the cities in the game are marked on the cloth map that came in the package, but just enough are left unmarked that you’ll need to to scour the whole map square by tedious square to find everything”

I never found exploring the Ultima worlds tedious. I played a pirated version of Ultima IV, so I never had the cloth map. When I put down hard-earned cash to purchase Ultima V, I was kind of disappointed that it came with a map! Everything was exposed, and some of the sense of exploration was gone. Luckily there was an underworld…

“One village sits at the center of a huge inland lake, its existence impossible to detect unless you happen to meet a pirate ship on the lake — a vanishingly unusual occurrence — fight it, steal it, and take it for a sail. Or you can find the village if you manifest an apparent death wish and sail a ship on the open ocean directly into a whirlpool. ”

The rareness of pirate ships was kind of annoying (being prone to chance). You do mention the alternative though. And this kind of stuff made the world feel like it was full of mystery. Hidden places that you had to work to get to. No hand-holding. It evoked a sense of exploration that is lacking in many modern games.

“Many of the towns and castles contain critical secret doors that are distinguished by the presence of one extra pixel amidst the grainy graphics.”

That’s a reasonable complaint, although it never bothered me too much.

“Each town or castle, which number sixteen in total, is populated with dozens of individuals. Miss that critical fellow hiding out in a visually impenetrable glade at the extreme edge of the map, and you’re screwed. Miss the single pixel representing a secret door, and you’re screwed.”

Well, the world wasn’t *that* big, it really wasn’t hard to explore it all. And unlike other RPGs of today that are filled with “drone” characters that have nothing interesting to say (and are just there to fill up the world), *everyone* in Ultima IV was important (except for the easily recognizable guards). Everyone had something interesting to say to further the plot along or help you find an item. To me, that encouraged you to explore everything, because you were bound to find something/someone useful. Of course, going back to the same places over and over just to “re-explore” could get tedious.

“In an interview for Computer Gaming World published shortly after the game, he let drop the bombshell that he was the only person who had managed to complete the game when Origin put it in a box and unleashed it on the world.”

Only person where? I didn’t have any help playing it (other than the fact that I played it with a friend). It did take a long time to finish, but we did complete the game without any hints/cheats.

Jimmy Maher

October 3, 2015 at 6:35 am

Garriott was the only person to complete the game during the testing process, which was severely curtailed by the need to get it out for Christmas 1985.

Alex Freeman

October 6, 2015 at 11:53 pm

I discovered this article while looking for mentions of Ultima IV on your site and originally thought of not asking since it’s been more than a year since you wrote, but since you’re still answering comments on it…

“Ultima IV boldly applies these sorts of mystical trappings to an ethical philosophy which carefully avoids the subject of God in favor of simple practicality… This has been expressed more rigorously by philosophers for millennia now as the idea of enlightened self-interest: you do best for yourself by doing well by others.”

Interesting, but I find that the game fails on its own terms in that case. Take these questions for instance:

Thee and thy friends have been routed and ordered to retreat. In defiance of thy orders, dost thou

A) stop in Compassion to aid a wounded

companion; or

B) Sacrifice thyself to slow the pursuing enemy, so others can escape?

If you sacrifice yourself, how is that in your own rational self interest? It’s not as if you’ll be around later to reap the rewards. Likewise:

Sacrifice vs. Humility:

Thou art an elderly, wealthy eccentric. Thy end is near. Dost thou

A) donate all thy wealth to feed hundreds of starving children, and receive public adulation; or

B) Humbly live out thy life, willing thy fortune to thy heirs?

If your end is near, how are you supposed to benefit from willing your fortune to your heirs? It seems only the first choice gives any kind of benefit.

“Parsing a distinction which admittedly really exists only in his mind, Richard claims to ignore morals, which to him represent decisions about right and wrong based on feelings or spiritual beliefs, in favor of ethics, which are grounded in simple, rational common sense.”

So what’s your take on meta-ethics? Moral realist? Moral relativist? Moral nihilist? Ideal observer theorist? Other? Not sure?

Jimmy Maher

October 7, 2015 at 9:36 am

That sort of romantic self-sacrifice has a lot of appeal to people, especially to many young people who so often tend to feel eternally misunderstood and unappreciated. Throw in Garriott’s ideals of chivalry inherited from the SCA, and it’s not hard to imagine how questions like these got in there, however they conflict with his own professed ethical framework.

Yes, there are plenty of flaws in Ultima IV’s system of ethics, others of which I tried to point out in the article. I think it’s important to remember that Ultima IV was written by a 23-year-old self-professed non-reader with a rather sheltered upbringing who was drawing largely from D&D, the SCA, and television documentaries. I don’t mean that to sound as dismissive as it may — Garriott was a *very* bright and in many ways a surprisingly thoughtful young man — but I think looking to Ultima IV for a completely air-tight ethical framework is asking far, far too much from it. (One might even say it was only Garriott’s naivete that allowed him to think he could formulate such a thing in the first place, after generations immemorial of philosophers and theologians had to one degree or another failed, for his nerdy game about killing monsters.) The most important thing was that it got so many kids thinking about these things in between killing monsters and collecting loot. Many doubtless pointed to the same discrepancies you just did — and that’s a very *good* thing.

I’d have to think long and hard to respond properly to your last question, as I’ve never really tried to fit myself into an ethical box before. I guess I’d call myself a moral realist when it comes to anything that hurts another (murder is absolutely wrong, as is more indirect harm like knowingly polluting the environment unnecessarily), a moral relativist on the many smaller issues (to be sexually promiscuous feels subjectively wrong to me personally, but I try to live and let live others who choose that lifestyle even as I’m unlikely to choose them as my close friends). Yes, I know such a system is no more air-tight than any other, but my years do perhaps give me an advantage over Garriott — at the time he wrote Ultima IV, that is — in that I know how messy it all really is. It’s going to be interesting to watch him come to that realization in Ultima V, an article I haven’t yet written.

I’m always a bard in Ultimas, if it helps. Compassion rules, other virtues drool! ;)

jeff

January 28, 2016 at 4:05 am

As a 10 year old playing this, I would say that the simple nature of the world and ability to explore in a non-linear fashion was unlike anything I had experienced before. To this day, I still remember finding cove and I was thrilled for weeks…

Hard to put myself in kids shoes today, but obviously the internet renders that type of experience moot… darn google can get you out of any jam

Erik

June 8, 2016 at 5:29 pm

This game had a big influence on my life. So much that I have a tattoo of TRUTH – LOVE – COURAGE to help me remember to become the person I want to be. It’s in runic, of course! :)

xxxxx

December 16, 2016 at 3:20 am

“the idea of Humility as literally an ethical vacuum seems truly bizarre.”

Humility is stated to be crucial to all other virtues, but is a virtue that simply doesn’t happen to be based on the three principles (one can be humble without Truth, Love, or Courage, though simply being humble doesn’t make you a good person). The virtues were also setup that way so that each configuration of the principles is represented in combinations of one, two, all three, or none. I’m not sure how you translate this to it being an “ethical vacuum”…?

“the idea that Spirituality is made up of all the virtues lumped together seems kind of strange”

As the game lore and the in-game dialogue explains, Spirituality has nothing to do with the traditional, religious usage of the word. In the context of Ultima IV, it refers strictly to the constant striving to know yourself and better one’s self and those around them (which is why Spirituality is advanced ingame by progressing on the quest of Avatarhood by finding quest items and visiting shrines). Ultimately the game teaches you that Avatarhood is a lifelong quest (and perhaps actual avatarhood doesn’t exist as result, which is sadly subverted by the rest of the games in the series constantly referring to you as the Avatar).

“One village sits at the center of a huge inland lake, its existence impossible to detect unless you happen to meet a pirate ship on the lake”

Cove doesn’t require a ship to detect; you can clearly see it using the balloon, and I’m pretty sure the telescope you can find hints at its location/presence. I can’t remember if you can use the balloon to get there because of the terrain or not, but you don’t need a ship since you can use the Blink spell to quickly and easily get to it when you know where it is (unless you’re playing the NES version where Blink only acts as an in-battle escape spell).

“out-of-left-field question whose answer requires the ability to read Richard Garriott’s mind, you’re screwed”

The game actually provides a few hints at this, but unfortunately the dialogue that’s supposed to appear was accidentally omitted. Still, the shrines do hint at this (the order each virtue appears to make up the ankh top to bottom, the order the final questions are asked, the order of the moon phases, everything hints at the order you’re supposed to read the runes).

The real trouble is if you don’t have the map for the game, which was the key to translating the runic alphabet used in the shrine hints. I didn’t when I initially played the game (used copy), and I think I accidentally got spoiled somehow when I first beat it.

Basically, you’re supposed to use the map to decipher the few letters needed in the answer (there’s only 5 different letters, and they all appear on the map very easily translatable once you learn the location names).

DZ-Jay

March 2, 2017 at 12:02 pm

>> “But you don’t spent all that large a percentage of your time…”

Should that be “you don’t spend”?

dZ.

Jimmy Maher

March 2, 2017 at 3:13 pm

Thanks!

DZ-Jay

March 2, 2017 at 6:13 pm

I want to thank you for another fantastically thought-provoking article. I never played the game, but I find it fascinating reading about the deconstruction of the author’s design process, and it’s creative evolution.

It almost makes me want to play the game. Almost. It’s not really my cup-o’-tea, then and now. ;)

dZ.

Mark Lemmert

March 12, 2017 at 1:16 am

Thanks for writing these reviews on Ultima I-V. For me they struck the perfect balance of really interesting and hilariously funny!

I agree wholeheartedly that exploration was the “killer app” of the Ultima approach to CRPGs. As I think back to playing Ultima IV in the 1980s, I remember things like mixing spells and endless pointless combat being tedious. For me the exploration was so exciting it overshadowed the rest. I mapped out every dungeon just to see what was (or wasn’t!) there.

I think you nailed it when you mentioned the context of the time, which made the tedium less of a factor. It was either that or play Apple panic :-) (I read that quip somewhere but I don’t recall the link).

On the whole, I still find the early Ultima playable, but I also realize that for many people, even those who played them in the 1980s, they are not. I’ve often wondered to what extend the 1980s tile-based CRPGs game style could be improved within the constraints of their original platforms. Essentially could the tedium be smoothed out without loosing the spirit of what made games like the early Ultima so much fun year ago.

Well, about a year and a half ago I decided to find out! I started a project of creating an Apple II tile-based RPG to do just that.

The game is called Nox Archaist:

http://www.noxarchaist.com

It will be available as a free download when released, expected late this year or early next year. It has been featured multiple times by Juiced.GS magazine and the Open Apple Podcast. Gameplay features are roughly in between Ultima V and VI. It will run on original Apple II hardware and on PCs and Macs via emulators.

The following is a list of the gameplay mechanics that I’ve attempted to improved. I thought this might be of interest as a perspective on the direction games like Ultima might have evolved into within the constraints of their original platform had development continued beyond the late 1980s.

Of course hindsight is 20/20 and I’m doing this with the benefit of seeing how modern game solved certain problems and then determining what is technologically feasible on the Apple II platform.

While some details may change before release the core of these features are all functional within the current Nox Archaist game engine.

—Alternative to mixing spells.

In Ultima, I thought herbs added an interesting dimension to magic in addition to magic points, but they were no doubt tedious to manage. Nox Archaist has magic points, and instead of herbs, mages will be required to learn new spells. Once a spell is learned it is never unlearned (i.e. think Skyrim not D&D)

—More intersting combat

*Automated target selection enables the player to flip through the available targets with the tab key. This is faster than directional system of Ultima IV, which arbitrarily limits available targets, and also faster than the cross hairs in Ultima V which requires arrowing over to each target manually.

*A exponential leveling modifier has been incorporated into in combat statistics. As a result, a high-level player coming back from the advanced dungeon just trying to get to the nearest town will quickly roll over the low level mobs hanging around most areas of the surface map.

*The player will see spell effects like exploding fireballs and flying lightning bolts. Complex tactical mechanics have been incorporated like critical hit and dodge/parry skills. In fact, character development is a skill based system with no set character classes. And, mob archers and spell casters are smart enough to try to take out the players archers and spell casters first.

*Combat is integrated into the storyline. For example, killing certain boss mobs may only be possible if the player has the benefit of knowledge and/or items acquired from various quests.

—More dynamic NPC conversations

*Nox Archaist’s conversations support three voice modes (yell, normal, whisper) and NPCs sometimes respond differently to the player depending on the volume of the players voice.

*Some NPCs will offer different information and/or respond to questions differently depending on the time or day or their location.

*NPCs have much greater awareness of events that have occurred in the game, allowing for a linear story to be embedded within an otherwise open world.

The goal of these conversation features is to encourage the player to take a more thoughtful approach than this reviews hilariously described “lawnmower” method to finding conversation clues. It also breaks the tradition of “talk to X about Y” being the primary conversational clue dispensing mechanic.

Mark

john

March 28, 2017 at 7:54 pm

So, I received this game for my C64 when I was 9, in 1986. I spent hundreds? of hours on it. I had a notebook, slam full with important words to ask people, sextant coordinates, vitrue/color/rune/stone relationships etc. I spoke to every single NPC in the game, slaughtered a billion monsters with A-E-H, and as a result I sit here today to tell you that it was, in fact, beatable without a walk-through by a kid with enough perseverance in less than 1 year. I will also tell you that the ankh did find its way onto a chain which I wore everywhere until I lost it on the tennis courts one day. Downloaded it from GoG a while back and quit playing it after a day because the thought of redoing all that work was daunting, and the thought of using a walkthough made me decide if I was going to do that “what’s the point”

Nice review. Glad I ran across it. Now I’ll be humming the songs for the rest of the day. 30 years later and I can remember every note.

Harland

March 29, 2017 at 9:42 am

It’s not that Dr. Abbot’s students thought Ultima IV was bad; it’s that they couldn’t be bothered to read the manuals and find out how to play. Good or bad, they never figured it out so the game isn’t being rated properly. The nauseating part was the teacher clearly told them to RTFM and they refused and then said the game sucked afterwards.

Jason Kankiewicz

April 12, 2017 at 1:00 am

“send a thrill up my spine” -> “send shivers up my spine”?

“blue is Truth, red Courage, yellow Compassion” -> “blue is Truth, red Courage, yellow Love”?

Jimmy Maher

April 13, 2017 at 8:30 am

The first is just another way of saying the same thing, but the second was a problem. Surprised nobody saw that before now. Thanks!

Unorus Janco

December 6, 2017 at 12:22 pm

Yeah, well, that’s just, like, your opinion, man.

Mike Taylor

March 26, 2018 at 11:39 pm

“Tomorrow Never Knows”, “Zoo Station”, “Living in Harmony” …

I wonder, did you ever watch Buffy the Vampire Slayer? There’s a similarly glorious what-that’s-not-what-I-expected at the start of Season 5. (I’ll say no more now for fear of spoilers.)

Jimmy Maher

March 27, 2018 at 6:42 am

No, afraid I haven’t…

Mike Taylor

March 27, 2018 at 8:49 am

I’ll just leave this here, ROT13’d, for anyone who’s interested.

Guebhtu gur svefg svir frnfbaf, Ohssl naq ure zbgure yvir nybar gbtrgure. Fhqqrayl ng gur fgneg bs Frnfba 5, Ohssl unf n grrantrq fvfgre jub rirelbar gnxrf sbe tenagrq nf gubhtu fur’f nyjnlf orra gurer — ab-bar pbzzragf ba ure neeviny. Vg ybbxf sbe nyy gur jbeyq yvxr n greevoyr pbagvahvgl reebe. Bayl nsgre sbhe rcvfbqrf bs vapernfvat orjvyqrezrag qb jr svanyyl svaq bhg, va Rcvfbqr 5, gung gurer vf na va-havirefr rkcynangvba sbe jul Qnja abj rkvfgf, naq abj nyjnlf unf qbar. Vg’f rkgerzryl nhqnpvbhf, naq chyyrq bss oevyyvnagyl.

(Only now do I realise how Lovecraftian ROT13 looks.)

Mike Taylor

March 26, 2018 at 11:53 pm

“The fact that the geography is completely different from that of the previous game is similarly handwaved away, attributed to a great upheaval — must have been one hell of an upheaval — following the destruction of Exodus in Ultima III.”

Well, there’s precedent. Don’t forget that Tolkien completely remade Middle-earth not once but twice: most radically after the fall of the great towers during the prehistory of the First Age, then again when the whole of Beleriand fell into the sea at the end of the First Age. You could even argue he did it a third time when the continent of Numenor sank at the end of the Second Age. (It’s all in the Silmarillion.)

Mike Taylor

March 27, 2018 at 12:16 am

“… and your chance for victory forsworn.”

I know you appreciate pedantry, otherwise I wouldn’t raise this. But “forsworn” connotes a deliberate decision to forego something — for example, a nun or a monk might forswear marriage. I think in this case, you just mean that the chance for victory is lost — very much inadvertently.

Jimmy Maher

March 27, 2018 at 6:44 am

Obviously Richard Garriott’s excruciating misuse of “Olde Time English” rubbed off on me. Thanks!

Scott M. Bruner

September 4, 2018 at 5:48 pm

This is an amazing read – especially the critical analysis of Garriott’s ethic system. In many ways, this does make Ultima V only the more impressive. Garriott, himself, operating in a field where few games were asking these sorts of compelling questions – was being critical of his own work. I think in an earlier article (about an earlier Ultima), it’s fascinating how most of us can forget the perspectives we held in adolescence, but Garriott’s were programmed permanently for dissection. I’m impressed with his ability to be self-critical…but I digress…