For ten very odd days during the late summer of 1866, the entire world directed its attention toward the tiny Newfoundland fishing village of Heart’s Content, population about 100 souls. Then the Great Eastern sailed again, and the telegraph house there became just another unnoticed part of the world’s communications infrastructure, one of those thousands upon thousands of installations that no one thinks about until they stop working. The once wondrous Atlantic telegraph cable itself joined the same category not long after, almost as soon as the Great Eastern completed the final part of its assignment for the year: that of fishing the broken cable from the previous year up out of the ocean’s depths and completing its run to Newfoundland. Thus well before the end of 1866, there were two Atlantic cables in service, the second providing additional bandwidth and, just as importantly, redundancy in the case of a break in the first. Never since has the link between the two continents been severed.

The Anglo-American Telegraph Company’s final bill for this permanent remaking of the time scale of international diplomacy, business, and journalism came to £2.5 million, equivalent to about £320 million or $430 million in 2022 currency; this total includes all of the earlier failed attempts to lay the cable, but ignores the costs to American and British taxpayers entailed by the loaning of the Niagara and the Agamemnon and many other forms of government support. Thanks more to Cyrus Field’s stubbornness than any grand design, the transatlantic cable had become an international infrastructure project more expensive than any yet undertaken in the history of the world. And yet in the long term the cost of the cable was paltry in comparison to how much it did to change the way all of the people of the world viewed themselves in relation to the rest of their planet.

In the shorter term, however, this latest, working transatlantic cable was greeted with fewer ecstatic poems and joyful jubilees than the sadly muddled one of 1858 had enjoyed. The reaction was especially muted in the United States. Perhaps the long years of war that separated the two events had made those old dreams of a new epoch of international harmony seem hopelessly quaint, or perhaps the impatient Americans just thought it was high time already that this cable they’d been hearing about for so long started working properly. One of the few eloquent exceptions to the rule of blasé acceptance was provided by a prominent New York attorney named William Maxwell Evans. He noted the inscription on the base of a statue of Christopher Columbus in Madrid: “There was one world. He said, ‘Let there be two.’ And there were two.” Now, said Evans, Field had dared to reverse Columbus: “There were two worlds. He said, ‘Let there be one.’ And there was one.”

In lieu of more windy speeches, the working transatlantic telegraph prompted “a commercial revolution in America,” as Henry Field puts it — prompted a whole new era of globalized trade which has changed more in magnitude than in character in all the years since:

Every morning, as [Cyrus] Field went to his office [in New York City], he found laid on his desk at nine o’clock the quotations on the Royal Exchange at twelve! Lombard Street and Wall Street talked with each other as two neighbors across the way. This soon made an end of the tribe of speculators who calculated on the fact that nobody knew at a particular moment the state of the market on the other side of the sea, a universal ignorance by which they profited by getting advances. Now everybody got them as soon as they, for the news came with the rising of each day’s sun, and the occupation of a class that did much to demoralize trade on both sides of the ocean was gone.

The same restoration of order was seen in the business of importations, which had been hitherto almost a matter of guess-work. A merchant who wished to buy silks in Lyons sent his orders months in advance, and of course somewhat at random, not knowing how the market might turn, so that when the costly fabrics arrived he might find that he had ordered too many or too few. A China merchant sent his ship round the world for a cargo of tea, which returned after a year’s absence bringing not enough to supply the public demand, leaving him in vexation at the thought of what he might have made “if he had known,” or, what was still worse, bringing twice too much, in which case the unsold half remained on his hands. This was a risk against which he had to be insured, as much as against fire or shipwreck. And the only insurance he could have was to take reprisals by an increased charge on his unfortunate customers.

This double risk was now greatly reduced if not entirely removed. The merchant need no longer send out orders a year beforehand, nor order a whole shipload of tea when he needed only a hundred chests, since he could telegraph his agent for what he wanted and no more. With this opportunity for getting the latest intelligence, the element of uncertainty was eliminated and the importer no longer did business at a venture. Buying from time to time, so as to take advantage of low markets, he was able to buy cheaper, and of course to sell cheaper. It would be a curious study to trace the effect of the cable upon the prices of all foreign goods. A New York merchant who has been himself an importer for forty years tells me that the saving to the American people cannot be less than many millions every year.

That said, it was the well-heeled who most directly benefited from the Atlantic cables in their early months and years. For all of William Thomson’s work, the bandwidth of each of them was still limited to little more than twelve words per minute, making them a precious resource indeed. The initial going rate for sending a message between continents was a rather staggering £1 or $7.50 per word, at a time when a skilled craftsman’s weekly wage might be around $10.

But that was merely the curse of the early adopter, something with which a technology-mad world would become all too familiar over the century and a half to come. In time, the pressure of competition combined with ever-improving cables and systems brought the price down dramatically. The Anglo-American Telegraph Company’s first competitor entered the ring already in 1869, when a French cooperative laid a cable of its own from Brest to Newfoundland and then on to Boston. By 1875, a transatlantic telegram cost a slightly more manageable $1 per word; by 1892, the price was down to 25¢ per word — still a stretch for the average American or European to use for private correspondence, but cheap enough for markets, businesses, governments, and news organizations to use very profitably, given their economies of scale. Soon “the wire” was synonymous with news itself.

By 1893, no fewer than ten transatlantic telegraph cables were in service, all of them transmitting at several times the speed of the cables of 1866; just seven years later, the total was fifteen. Other undersea cables pulled India, Australia, China, and Japan into this first worldwide web. It was now possible to send a message from any reasonably sized city in the world all the way around the world, until it made it back to its starting point from the opposite direction just a few hours later.

Henry Field again, writing in 1893:

The morning news comes after a night’s repose, and we are wakened gently to the new day which has dawned upon the world. That which serves to such an end, which is a connecting link between countries and races of men, is not a mere material thing, an iron chain, lying cold and dead in the icy depths of the Atlantic. It is a living, fleshly bond between severed portions of the human family, thrilling with life, along which every human impulse runs swift as the current in human veins, and will run forever. Free intercourse between nations, as between individuals, leads to mutual kindly offices that make those who at once give and receive feel that they are not only neighbors but friends. Hence the “mission” of submarine telegraphy is to be the minister of peace.

Sentiments like these had once again become commonplace even in the United States by the end of the nineteenth century, as the memories of civil war faded. It was now widely believed that the developed world at least had become too intimately intertwined, thanks largely to the telegraph, to ever seriously contemplate war again. The bloody twentieth century to come would prove such sentiments sadly naïve, but it was a nice thought while it lasted. (Internet idealists would of course be slowly and painfully disabused of much the same sentiments a century later; human technology, it seems, cannot so easily overcome human nature.)

By the time the century turned, the machines and men who had created this revolution in communications were mostly gone.

The Great Eastern, that colossal white elephant that had finally found a purpose with the laying of the first transatlantic cables, continued in its new role for some time thereafter, laying three further cables across the Atlantic and still more of them in the Indian Ocean, the Pacific, and the Mediterranean. But its new career was ended by the completion of the CS Faraday, the first ship designed from the hull up for the purpose, in 1874; this vessel could lay cables far cheaper and more efficiently. Cast adrift on the waters of life once more with no clear purpose, the Great Eastern spent some time as a floating concert hall and tourist attraction, even at one point became a mobile billboard sailing up and down the Mersey River. Its glory days now a distant memory, the rusting hulk was sold for scrap in 1888.

The Great Eastern near the end of its days, when it was reduced to serving as a floating billboard for Lewis’s department stores.

Charles Bright died the same year at age 55, after a high-profile public career as a proponent of electrical technology in all its forms and a three-year stint in the House of Commons.

William Thomson was blessed with a longer, even more spectacular career that encompassed a diverse variety of achievements in the theoretical and applied sciences, from atomic physics to geology, as well as five years spent as the president of the Royal Society. In 1891, Queen Victoria ennobled him, making him Lord Kelvin, after the river that flowed through the University of Glasgow where he taught and researched. He didn’t die until 1907 at age 83, whereupon he was given a funeral in Westminster Abbey commensurate with his status as the grand old man of British science. A system for measuring temperature on an absolute thermodynamic scale, which he had first begun working on well before the transatlantic cable, became known after his death as “the kelvin scale” by the universal consensus of the international scientific community.

His erstwhile arch-rival Wildman Whitehouse, on the other hand, shrank from public life after it became clear to everyone that he had been wrong and Thomson had been right about the best design for the first Atlantic cable. When Whitehouse died in 1890 at age 73, the event went entirely unremarked.

Cyrus Field was made richer than ever for a while by the transatlantic telegraph. He splashed his millions around Wall Street both in the hope of making more millions and out of that spirit of idealism that was such an indelible part of the man’s character. For example, he funded much of the construction of New York City’s “El” lines of elevated trains, the precursor to its current subway system, by all indications out of a simple conviction that the people of the city deserved better than “crowded to suffocation” streetcars. Prone as he was to prioritize his ideals over his pocketbook, he gradually fell back out of the first rank of Gilded Age money men. He died in 1892 at age 72, whereupon he was buried behind the family church in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. His unremarkable gravestone bears an epitaph that is as straightforward as the man himself:

Cyrus West Field, to whose courage, energy, and perseverance the world owes the Atlantic telegraph.

Samuel Morse, that brilliant but deeply flawed original motivating force behind the telegraph, left behind a more mixed legacy. Even as Field had been struggling to make the transatlantic telegraph a reality, Morse had taken to occupying himself mostly with litigation of one form or another; cases brought by him reached the Supreme Court on no fewer than fifteen separate occasions. When Morse died in 1872 at the age of 80, his private reputation inside a telegraph industry that publicly eulogized him wasn’t much better than that of the typical patent troll of today, thanks to his meanness about payments and credit. Thankfully, his telegraph patents had expired eleven years earlier, which had served to draw the worst of his venom. Morse’s design for the telegraph itself as well as for the Morse key and Morse Code had thus been freed to take on a life of their own independent of their inventor, as all important inventions eventually must.

In addition to changing the world in the here and now, those same inventions paved the way for the next stage in the evolution of the global village. What that stage might entail had begun to show itself already one day in May of 1846, when the telegraph in service was still a curiosity and the idea of a transatlantic telegraph still a pipe dream. On the day in question, Joseph Henry — the most respected American theoretical scientist of telegraphy, whose advocacy had been so crucial for winning support for Morse’s design — happened to be visiting Philadelphia, where he was invited to witness a mechanical “speaking figure” created by a German immigrant named Joseph Faber. The automaton could, it was claimed, literally speak in recognizable English. Henry always took a certain ironic pleasure in revealing the fraud behind inventions that seemed too good to be true, a species to which he surely must have suspected Faber’s speaking figure to belong. But what he saw and heard that day instead thrilled him in a different way.

The astute German’s contraption took the physical form of a Turkish-looking boy sitting crossed-legged on a table. Faber made it “talk” by forcing air through a mechanical replica of the human mouth, tongue, glottis, and larynx, which could be reconfigured on the fly to produce any of sixteen elementary sounds. By “playing” it on a repurposed organ keyboard, Faber could indeed bring his puppet to produce labored but basically comprehensible English speech. Joseph Henry was entranced — not so much by the puppet itself, which he rightly judged to be no more nor less than a clever parlor trick, but by the potential of combining mechanical speech with telegraphy. “The keys,” he noted, “could be worked by means of electromagnets, and with a little contrivance, not difficult to execute, words might be spoken at one end of the telegraph line which had their origin at the other.” It was the world’s first documented inkling of the possibility of a telephone — a tool for “distant speaking,” as opposed to the “distant writing” of the telegraph. That tool, when it came, would transmit the speech of real humans rather than a synthetic version of it, but Henry’s words were nonetheless prescient.

Many of the others who saw Faber’s automaton were less thrilled. The very idea of the human voice being reproduced mechanically had an occult aura about it in the mid-nineteenth century. It thus comes as little surprise that the legendary showman and conman P.T. Barnum, who specialized in all things uncanny and disturbing, recruited Faber and his artificial boy for one of his traveling exhibitions. In this capacity, the two made their way across the Atlantic to London’s Egyptian Hall. The description provided by one witness who saw them there sounds almost like an extract from a macabre tale by Edgar Allan Poe or H.P. Lovecraft:

The exhibitor, Professor Faber, was a sad-faced man, dressed in respectable well-worn clothes that were soiled by contact with tools, wood, and machinery. The room looked like a laboratory and workshop, which it was. The professor was not too clean, and his hair and beard sadly wanted the attention of a barber. I had no doubt that he slept in the same room as the figure — his scientific Frankenstein monster — and I felt the secret influence of an idea that the two were destined to live and die together. The professor, with a slight German accent, put his wonderful toy in motion. He explained its action: it was not necessary to prove the absence of deception. The keyboard, touched by the professor, produced words which slowly and deliberately in a hoarse sepulchral voice came from the mouth of the figure, as if from the depths of a tomb. It wanted little imagination to make the very few visitors believe that the figure contained an imprisoned human — or half human — being, bound to speak slowly when tormented by the unseen power outside.

As a crowning display, the head sang a sepulchral version of “God Save the Queen,” which suggested inevitably God save the inventor. This extraordinary effect was achieved by the professor working two keyboards — one for the words and one for the music. Never probably before or since has the national anthem been so sung. Sadder and wiser, I and the few visitors crept slowly from the place, leaving the professor with his one and only treasure — his child of infinite labour and unmeasurable sorrow.

Alas, Joseph Faber met a fate worthy of an Edgar Allan Poe protagonist. Exploited and underpaid like all of P.T. Barnum’s entourage of curiosities, he committed suicide in 1850 on the squalid streets of London’s East End.

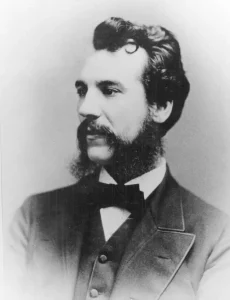

Before he did so, however, there came to his room in the Egyptian Hall one open-minded visitor who was more fascinated than appalled by the performance: a Scottish phonetician named Alexander Melville Bell, who had spent most of his life studying the mechanisms of speech in the cause of teaching the deaf to communicate with the hearing. This man’s son, who was still in the womb when his father saw Faber’s automation, would go on to create a different form of mechanical speech, making his family name virtually synonymous with the telephone.

Alec is a good fellow and, I have no doubt, will make an excellent husband. He is hot-headed but warm-hearted — sentimental, dreamy, and self-absorbed, but sincere and unselfish. He is ambitious to a fault, and is apt to let enthusiasm run away with judgment. I have told you all the faults I know in him, and this catalogue is wonderfully short.

— Gardiner Greene Hubbard, writing to his daughter Mabel on the subject of Alexander Graham Bell

When a 23-year-old Alexander Graham Bell fetched up on North American shores from his hometown of Edinburgh on August 1, 1870, he resembled a sullen, lovesick adolescent more than a brilliant inventor. Earlier that year, his elder brother had died of tuberculosis. Devastated by grief, disappointed at the cool reception his techniques for teaching the deaf to read lips and to enunciate understandable speech in return had garnered in Britain, his father Alexander Melville had opted for a fresh start in Canada. The younger Alexander had initially agreed to join his father, mother, and widowed sister-in-law in the adventure, but almost immediately regretted it, thanks not least to a girl in Edinburgh whom he hoped to marry. But his pointed hints about his change of heart availed him nothing; his father didn’t let him off from his promise. On the passage over, young Alexander filled his journal with petulant musings about how “a man’s own judgment should be the final appeal in all that relates to himself. Many men do this or that because someone else has thought it right.”

But he wasn’t a malcontent by nature, and he soon made the best of things in the New World. Like his father, he would always consider his true life’s calling to be improving the plight of the deaf. Their dedication had a common source: Eliza Bell, Alexander Graham Bell’s mother, was herself so hard of hearing as to be effectively deaf. In April of 1871, her son became a teacher at the School for Deaf Mutes in Boston. A kindly, generous man at bottom, he approached his work there with an altruistic zeal. “My feelings and sympathies are every day more and more aroused,” he wrote home to his family. “It makes my very heart ache to see the difficulties the little children have to contend with.”

He wasn’t just empathetic; he was also effective. By combining instruction in elocution and lip-reading with sign language, he did wonders for many of his students’ ability to engage with the hearing world around them. He wrote articles for prestigious journals, and earned the reputation of something of a miracle worker among the wealthy families of New England, who clamored to employ him as a private tutor for their hearing-impaired children.

Worthy though Bell’s work as a teacher of the deaf was, it would seem to be far removed from the telegraph and other marvels of the burgeoning new Age of Electricity. But there was another side to Alexander Graham Bell. His interest in elocution in the abstract had led from an early age to an interest in the biological mechanisms of human speech, and possible ways of artificially reproducing them. When he was just sixteen, he and his now-deceased brother had made a crude duplicate of a human soft palate and tongue out of wood, rubber, and cotton; by manipulating it in just the right way whilst blowing through an attached tube, they could get it to say a few simple words like “Mama.” One day when they were playing with it on the stairwell outside the family apartment, a neighbor poked her head out to see “what was wrong with the baby”; they viewed this as a triumph. Now the boys’ focus shifted to the family dog. They trained it to growl on cue while they manipulated the poor, patient animal’s mouth and throat — and out came some semi-recognizable facsimile of, “How are you, grandmama?”

Needless to say, the young Alexander had listened to his father’s stories of Joseph Faber’s talking automaton with rapt attention. Another phonetician told him that another German scientist and inventor by the name of Hermann von Helmholtz had recently written a book on the possibility of synthetic speech. It explained how vowel sounds could be generated by passing electrical currents through different combinations of tuning forks. The operator sat behind a keyboard not dissimilar to the one used by Faber, and like him pressed different combinations of keys to make different sounds; the big difference was that, while Faber’s puppet was powered by compressed air, Helmholtz’s gadget was entirely electrical. But Bell didn’t read German, and so could do little more than look at the diagrams of Helmholtz’s device that were included in the book. This led to an important misunderstanding: whereas in reality each tuning fork was connected to the master keyboard via its own wire, Bell thought that one wire passed through all of the forks, and that it was the characteristics of the current on that wire — more specifically, its frequency — that caused some of them to ring out while others remained silent. “The notion was entirely mistaken,” writes the historian of telephony John Brooks, “but the mistake was an accident of destiny.”

Bell’s destiny became manifest on October 18, 1872, when he opened a Boston newspaper to see an article about the “duplex telegraphy” system of a local man named Joseph B. Stearns. An important advance in the state of the art of electrical communication in its own right, duplex telegraphy allowed one to send separate messages simultaneously in opposite directions along a single telegraph wire. In a world where telegraph congestion was becoming a major issue, this was a more than significant gain in efficiency. Being quite fast and cheap to retro-fit onto existing telegraph lines in busy areas, Stearns’s system would soon become commonplace. But already other inventors were beginning to think about how to go even farther, how to send even more messages simultaneously down a single wire. Oddly enough, Alexander Graham Bell, teacher of the deaf, became one of these.

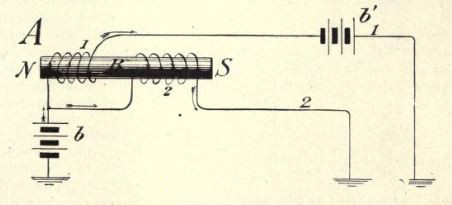

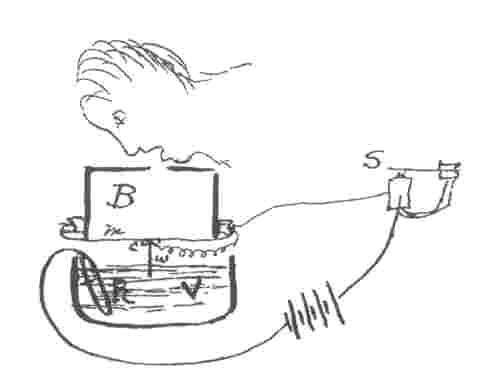

Joseph Stearns’s ingenious system for duplex telegraphy, which inspired Alexander Graham Bell’s initial investigations in the field. B in the diagram above is an iron bar. The wire running from the local battery (b) is split in two. Both of these wires are wound around the bar, but only wire 1 goes on to connect with the station at the other end of the line; wire 2 runs directly to ground. An electromagnetic switch is connected to the bar at N, and to the other side of this switch is connected the receiving apparatus. Because a locally generated signal passes evenly through the bar, the bar does not become magnetically unbalanced, and thus does not activate this switch. But a signal originating from the other station passes through only half of the bar, magnetizing it and tripping the switch, which allows the signal to go on to the receiving apparatus.

Bell’s idea was to pass the signal from each of several Morse keys attached to a single wire through a device known as a rheotome, which interrupted the flow of an electrical current at a user-adjustable speed, causing it to “vibrate” at a distinct frequency — akin to a distinct pitch when thought of in acoustic terms, as Bell most assuredly did. At the far end of the line would be a set of steel reeds attuned to each of these frequencies via tension screws, so that they would resonate and become magnetized only when their matching frequency reached them. These reeds, in combination with electromagnetic switches which they would trigger, would serve to sort out all of the different frequencies coming down the same wire, matching each Morse key at the sending end with the appropriate receiver by means of its unique electro-acoustic thumbprint. By the end of 1873, however, Bell had gotten only as far as being able to produce audible, simultaneous tones on his receiving reeds by pressing different Morse keys; he had done little more than duplicate the functionality of Hermann von Helmholtz’s vowel-speaking machine, albeit by wiring his reeds serially rather than in parallel like Helmholtz’s tuning forks.

Nevertheless, in January of 1874 Bell, still a loyal Briton despite his residency in the United States, wrote to the British Superintendent of Telegraphs explaining that he believed himself to be on the verge of an important breakthrough in the emerging field of multiplex telegraphy, one which he wished to offer to Her Majesty’s government free of charge. The reply was coldly impersonal, not to say disinterested: “If you will submit your invention it will be considered, on the understanding, however, that the department is not bound to secrecy in the matter, nor to indemnify you for any loss or expense you may incur in the furtherance of your object, and that in the event of your method of telegraphy appearing to be both original and useful, all questions of remuneration shall rest entirely with the postmaster-general.” Bell understandably took this as “almost a personal affront,” and decided to turn to private industry in the United States instead. The whole incident thus became another of those hidden, fateful linchpins of history. In so rudely rejecting its citizen inventor, the British government ensured that the telephone, like the telegraph before it, would go down in history as a product of the American can-do spirit.

Then again, the British government’s skepticism about this amateur inventor working so far outside of his usual field would scarcely have been questioned by any reasonable person at the time. Bell was not deeply versed in the vagaries of electricity, and his progress always seemed to be a matter of two steps forward, one step back — or the inverse.

Still, his experiments were intriguing enough that he attracted a pair of patrons, both of whose deaf children he had taught. Thomas Sanders was a wealthy leather merchant, while Gardiner Greene Hubbard was a prominent lawyer and public-spirited scion of old Boston wealth. Of the two, Hubbard would take the more active role, becoming at some times a vital source of moral support for Bell and at others a vexing micromanager. Their relationship was further complicated by the fact that Bell was desperately in love with Hubbard’s deaf daughter — and his own former student — Mabel.

Sanders and Hubbard joined their charge in forming the Bell Patent Association. They provided him with his first proper workshop and hired a part-time assistant to join him, a young machinist named Thomas A. Watson. Bell and Watson became fast friends despite their differences in socioeconomic status, their rapport taking on something of the flavor of another famous pairing which involves the name of Watson; instead of “Elementary, my dear Watson,” Bell’s catchphrase became, “Watson, we are on the verge of a great discovery!” And yet their demonstrable progress remained damnably slow. Even with the help of his assistant, who had many of the practical skills he lacked, Bell just couldn’t seem to get his “harmonic telegraph” to work reliably.

Everyone involved was keenly aware that Bell was not the only person in hot pursuit of further advances in multiplex telegraphy. Among his competition were the distinguished electrical engineer Elisha Gray, co-founder of a company known as Western Union that had come to dominate virtually all American telegraphy, and a young whiz kid named Thomas Edison. Bell was in a race, one that he felt himself to be losing to these men of vastly greater experimental know-how, who lived and breathed electric current in a way that he never would. Trying to keep up nearly killed him; he was still spending his days teaching the deaf students he couldn’t bear to abandon, even as he spent every evening in his laboratory.

From the perspective of today, it may seem that Bell was missing the forest for the trees as he continued to fashion ever more baroque devices for combining and then separating signals of different frequencies running down the same wire. He understood well that an electrical waveform could theoretically be made into an exact duplicate of a sound wave; all of his work was contingent on the similarities between the two. Yet it took him a long time to fully embrace a goal which seems obvious to us: that of transmitting sound electronically as a purpose unto itself, a revolutionary advance to which any potential incremental advances in multiplex telegraphy couldn’t hold a candle.

There was one central problem which prevented Bell from making that leap: he knew how to create an electronic waveform that captured only half of the data encoded by a sound wave in the real world. His circuits were all powered by an external battery, providing direct current at a fixed amplitude. He could vary the frequency of this current using a rheotome, but he had no way of changing its amplitude. In other words, he could transmit a sound’s pitch (or frequency) but not its volume (or amplitude). This meant that he could mimic uniform tones in electric current, but not the complexities of, say, human speech.

June 2, 1875, was a miserably hot day in Boston. Bell and Watson were working in a rather desultory fashion on their harmonic telegraph in their cramped laboratory; their progress of late had been as slow as ever. Bell was on the sending end in one room, Watson on the receiving end in the other, and, as usual, the thing wasn’t working correctly; one reed on the receiving end stubbornly refused to sound. So, they shut down the battery, and Watson started plucking the recalcitrant reed to make sure it was free to move as it should.

Because the system would need to be able to send messages in both directions, it was equipped with both rheotomes and receiving reeds on each of its ends. But, because they weren’t in use at the moment, the reeds on Bell’s end had been left untuned. And it was these latter that now gave Alexander Graham Bell one of the shocks of his life: he found that he could see and faintly hear the reeds on his side vibrate in time with Watson’s plucking, even with no power flowing through the circuit. He realized that a residual magnetism in Watson’s reed must be creating a faint electrical signal of its own on the wire. And, crucially, this signal varied not just in pitch but in amplitude. It seemed that one counterintuitive trick to sending sound down a wire was to remove the amplitude-obscuring battery from the circuit entirely. “I have accidentally made a discovery of the greatest importance,” Bell wrote in a letter to Hubbard. “I have succeeded today in transmitting signals without any battery whatsoever!” The harmonic telegraph was momentarily forgotten in favor of this new possibility.

Bell sketched for Watson a design that used identical devices on each end of a wire for both sending and receiving the spoken word. They consisted of a single untuned metal reed, an electromagnet, and a thin diaphragm. If one spoke into one of them shortly after power had been supplied to the wire — i..e, when the electromagnets still retained some residual magnetism — the resulting vibrations of the diaphragm ought to induce a very faint electrical signal of the same character as the sound wave that had caused the vibration. At the other end of the wire, this signal would be translated back into sound when it caused the reed to vibrate.

Alexander Graham Bell’s very first attempt at a telephone, using unpowered magnetic induction. It was later given the rather morbid nickname of the “gallows telephone,” after its resemblance to an execution gallows when turned on end.

Experts who have looked at the design since have concluded that it is workable in principle. In practice, however, it stubbornly refused to function properly. Bell and Watson just couldn’t seem to get the fine-tuning right, could get it to transmit some form of sound but not comprehensible speech. The Achilles heel of the “magnetic induction” method of sound transmission was the vanishing faintness of the signals it produced. Even under perfect conditions, a human voice could reach the other end of a wire as the barest whisper, audible only to a person with very keen hearing — and the slightest technical infelicity would mean it couldn’t even manage that much.

Faced with this latest setback, and with his harmonic telegraph also seemingly going nowhere, Alexander Graham Bell came very close to giving up on electrical invention altogether. He and Watson were both utterly frazzled, having worked themselves to the bone in recent months. Gardiner Hubbard remained enthusiastic about telegraphy, but was less interested in telephony, and didn’t hesitate to tell Bell this. Bell himself now believed that his harmonic telegraph stood little chance against its competition even if he could get it working — by now Thomas Edison had already patented a design for a telegraph capable of sending four messages simultaneously down the same wire — but he hesitated to say as much to his prospective father-in-law. Instead he prevaricated, devoting more time and energy once again to his teaching. Needless to say, this too displeased Hubbard. “I have been sorry to see how little interest you seem to take in telegraph matters,” he wrote to Bell that fall. “Your whole course has been a very great disappointment to me, and a sore trial.” What Bell and Hubbard didn’t know, but would doubtless have been even more consternated to learn, was that Elisha Gray had also turned away from multiplex telegraphy in the wake of Edison’s patent and begun pursuing the possibility of telephony.

What time Bell did spend on his electrical pursuits during the second half of 1875 was largely devoted to preparing a patent application for his inventions, even though none of them quite worked yet. Hubbard helped him to file it, on February 14, 1876. Incredibly, just a few hours later on that same day Gray filed a “caveat” — a claim of primacy submitted before a formal patent application — detailing his plans for a “speaking telephone.” Had the order been reversed, the history of the telephone in service might have gone much differently, with the name of “Gray” replacing that of “Bell” in the annals of invention.

But as it was, Bell’s own patent application, which was approved on March 7, 1876, would go on to become one of the most valuable and controversial in American history. To say it buries the lede is an understatement: rather than Gray’s speaking telephone, it promises only “improvements in telegraphy,” never even using the word “telephone.” And rather than the transmission of intelligible speech, it promises only the transmission of “vocal or other sounds” — which was accurate enough, considering that this was all that Bell and Watson had managed to date by even the most generous possible interpretation.

Still, the patent filing did reinvigorate the young inventor and his assistant: they returned to their laboratory and began working in earnest again. The day after his patent was approved, Bell was futzing about alone when he did something that seems almost inexplicable on the face of it, being out of keeping with all of his experiments to date. First he attached a battery to a wire. He then split one end of the wire into two leads, running one of them to a tuning fork and dropping the other into a dish of water. At the other end of the wire he attached one of his metal reeds, but left it untuned so that it would vibrate freely in response to any signal. He tapped the tuning fork to make it vibrate and dipped one of its arms into the dish of water, whereupon he was rewarded with a “faint sound” from the reed. Excited now, he added some sulfuric acid to the water to make it a better conductor, then repeated the experiment. Sure enough, the sound from the reed got louder. He attached the lead in the water to a submerged ribbon of brass, and the sound got louder still.

What was happening here? The liquid in the dish and the metal of the tuning fork both being conductive, they were serving to bridge the two leads, allowing the current from the battery to flow between them. But the vibrations of the tuning fork were varying the resistance of the circuit, which in turn varied the frequency and amplitude of the current flowing along it. This “variable resistance” method of transmitting a sound wave was far superior to the unpowered magnetic induction Bell had been relying on earlier, which had been able to create the merest trace of a signal on the line. This signal, by contrast, was stronger to begin with, and could be further amplified to whatever extent one desired simply by using more and/or larger batteries. It was the great breakthrough on the road to a practical, usable telephone. Bell immediately went in search of Watson.

Two days later, all was in readiness for the pivotal test. Watson, who had by now taken on a recording function for the duo’s adventures not that far removed from his literary namesake, describes the scene:

I had made Bell a new transmitter, in which a wire, attached to a diaphragm, touched acidulated water contained in a metal cup, both included in a circuit through the battery and receiving telephone. The depth of the wire in the acid and consequently the resistance of the circuit was varied as the voice made the diaphragm vibrate, which made the galvanic current undulate in speech form.

At the other end of the wire was of course an untuned metal reed, waiting to receive whatever electrical signal came down the wire and turn it back into sound waves.

Bell took his spot at the transmitting station, while Watson went to the receiving station behind a closed door in the adjacent room. And then Watson heard the canonical first words ever spoken into a working telephone: “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.”

I rushed into his room and found he had upset the acid of a battery over his clothes. He forgot the accident in the joy of his new transmitter when I told him how plainly I had heard his words.

The two men spent hours running between the rooms testing out their contraption, which did indeed work — not perfectly, mind you, but vastly more reliably than anything they had created to date. In an inadvertent homage to poor Joseph Faber, Bell concluded the evening’s festivities by singing “God Save the Queen” into the wire. “This is a great day with me,” he wrote. “I feel that I have at last struck the solution of a great problem — and the day is coming when telegraph [sic] wires will be laid on to houses just like water or gas — and friends converse with each other without leaving home.” The words were prescient. Alexander Graham Bell, elocutionist and teacher of the deaf, working alone except for one talented assistant, had invented the telephone before anyone else.

Or had he?

In the very near future, individuals and courts would come to speculate endlessly about where the sudden burst of insight that a sound wave could be transmitted on a powered wire by varying the circuit’s resistance had actually come from. The possibility is mentioned in Bell’s patent application, but only as a last-minute, hand-scrawled notation in the margin. Elisha Gray’s patent caveat, by contrast, includes not only the principle but a detailed description of how a transmitter very similar to the one Bell employed might be made, right down to a diaphragm with a lead dangling into a dish of acidulated water. Bell himself wrote in a letter to his father that he had become friendly with the clerk who had accepted both documents, and continued to talk with him regularly while his own patent was going through the approval process. Did the clerk let slip these details of Gray’s design, or possibly even allow Bell to look at the document itself? Did he let Bell add that crucial note to the margin of his own patent application after its submission? (Bell did later acknowledge that he was allowed to “clarify” some other terms that the patent office deemed too vague in the first draft.) All of these things would soon be insinuated in court.

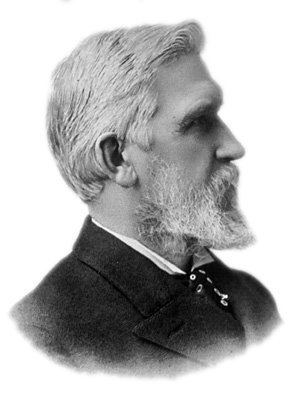

Elisha Gray, the man who some insist deserves at least equal credit with Alexander Graham Bell for the invention of the telephone.

Alexander Graham Bell’s personal papers did provide some exculpatory evidence after they were donated to the Library of Congress in 1976. Bell’s notes show that he was thinking about the potential of using variable resistance to transmit sound as early as May 4, 1875, and even conducted some experiments in that direction shortly thereafter. Likewise, he did tinker with “liquid transmitters” from time to time prior to that fateful date of March 8, 1876. Still, he never thought to combine a transmitter using acidulated water with the principle of variable resistance until suspiciously close to the moment that Elisha Gray submitted a detailed plan for doing so to a man with whom Bell later had several fairly long conversations. The evidence is highly circumstantial, to be sure, but is no less hard to discount entirely for that. Historians have combed through all of the relevant papers thoroughly without finding any more definitive smoking gun pointing one way or the other. It seems that the truth of the matter will never be known with complete certainty.

On the other hand, if we judge that the credit for an invention should go to the first person to make a working version of it, full stop, then we can comfortably declare Alexander Graham Bell to be the inventor of the telephone; there is no suggestion that Gray actually built the telephone he designed on paper prior to Bell’s first successful test on March 10, 1876. The whole controversy serves to remind us that any remotely modern technology is a mishmash of ideas and discoveries, and the order and primacy of the whole is not always as clear as we might wish.

At any rate, the telephone was now a reality. And now that it was invented, it needed to be put into service.

(Sources: the books The Victorian Internet by Tom Standage, Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity Before Edison by Michael B. Schiffer, Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F.B. Morse by Kenneth Silverman, A Thread across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Telegraph by John Steele Gordon, The Story of the Atlantic Telegraph by Henry M. Field, Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude by Robert V. Bruce, Alexander Graham Bell: The Life and Times of the Man Who Invented the Telephone by Edwin S. Grosvenor, Reluctant Genius: Alexander Graham Bell and the Passion for Invention by Charlotte Gray, Telephone: The First Hundred Years by John Brooks, and American Telegraphy and Encyclopedia of the Telegraph by William Maver, Jr. Online sources include History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications and “Joseph Faber and the Euphonia Talking Device” at History Computer.)

Roberto

February 18, 2022 at 6:57 pm

Somebody wouldn’t agree, I guess.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Meucci

By the way thanks for your encyclopedic work, I really appreciate it.

Gio

February 19, 2022 at 11:41 am

Typical american approach: taking innovative ideas from Europeans and telling they were created by yankees…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Meucci#Invention_of_the_telephone

Give credits to some other telephone pioneers, as well:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Bourseul

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Philipp_Reis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Innocenzo_Manzetti

Mike K

February 18, 2022 at 7:35 pm

Thoroughly enjoying this series of articles!

Dan V.

February 18, 2022 at 11:31 pm

Minor nitpick: “and a young whizz kid named Thomas Edison” should be whiz with one Z. A whizz kid would be doing something else.

Great work on this series, by the way.

Jimmy Maher

February 19, 2022 at 7:35 am

Thanks!

Rowan Lipkovits

February 19, 2022 at 1:53 am

“after his death by the universal consensus of the international scientific community”

I don’t know if this wants a comma or what, but it sounds like an incredible spin on the “Murder on the Orient Express” twist.

Jimmy Maher

February 19, 2022 at 7:37 am

Ah, I see how you read that… Thanks!

Ian Crossfield

February 19, 2022 at 2:26 am

We’ve come a long way since Getting Lamps and Hunting Wumpus… still enjoying the ride.

Aula

February 19, 2022 at 7:16 am

“Never since has the electrical link between the two continents been severed.”

All current (and presumably future) transatlantic cables use optical fiber instead of electric wire, so “electrical” isn’t the right word.

Jimmy Maher

February 19, 2022 at 7:38 am

Thanks!

Tuna

February 19, 2022 at 6:15 pm

While the data travels as photons in fiber, submarine optical cables also contain an electrical cable (typically very high voltage DC). Light can only make so far in glass, and so all current long cables contain repeaters at steady intervals, and they need to be powered.

Interestingly, this might actually change in the reasonably near future. ZBLAN fiber manufactured in microgravity can be clear enough that you can push the same signal across an ocean without using any repeaters. This is often considered one of the very few candidate products that can only be manufactured in orbit, and which would be sufficiently valuable to make setting up orbital manufacturing worth it.

Daniel Wolf

February 19, 2022 at 7:52 am

I was a bit confused when I read the first long quotation starting with “Every morning, as Mr. Field went to his office”. Is this Henry Field talking about himself in the third person?

Also, on a purely stylistic note, I noticed the word “stint” twice in two consecutive sentences; maybe one could be rephrased.

Jimmy Maher

February 19, 2022 at 8:11 am

He’s talking about Cyrus Field. Added an emendation to reflect that. Thanks!

Martin

February 20, 2022 at 12:21 am

Serious question. So when did the classic two cans and a string ‘telephone’ come from?

Gnoman

February 20, 2022 at 1:00 am

Mid 1600s is when the device is first described. Purely acoustic devices of this sort were tinkered with for a very long time before the invention of the electronic telephone, and were quite common by the 19th century.

This is one of the big areas where Meucci’s claim to the telephone runs aground – it is certain that he built multiple acoustic speaking devices that may have had an electrical component, but it is far from certain that he made the leap to a full-electric system before Bell did.

Peter Olausson

February 20, 2022 at 10:02 am

What a plot twist to realise William Thomson was Lord Kelvin. Fantastic.

And a terrific side quest, this “victorian Internet” thing. Keep it up!

Nate

February 22, 2022 at 10:23 pm

I’m also enjoying these adventures in communications.

I find the switch between currencies jarring in these passages. It makes them hard to compare:

“rather staggering £1 or $7.50 per word, at a time when a skilled craftsman’s weekly wage might be around $10.”

“a slightly more manageable $1 per word; by 1892, the price was down to 25¢ per word”

Perhaps you could convert all of them to one currency (in the same year) for the sake of comparison?

Martin

February 24, 2022 at 4:15 pm

If the exchange rates remained constant that would make sense but as the pound to dollar exchange rate has changed significantly, one value (either one) would make little sense for users of the other currency.

Whomever

February 25, 2022 at 2:28 pm

I disagree with this (converting currency). The reason is that it’s not really a simple relationship; the exchange rate between £ and $ has radically changed over time, and inflation is not just a simple thing of “all prices rise at the same time”. See eg https://fullstackeconomics.com/why-agatha-christie-could-afford-a-maid-and-a-nanny-but-not-a-car/ for an article that has been going around recently that perfectly illustrates this. The original prices have context which would be lost.