Ultima V is a story about freedom of choice. You can’t put these [the eight Virtues] down as laws. It does not work to put these down as laws. They’re fine as a point of discussion, but it’s a completely personal issue. I would never try to build a pseudo-science of truth. This is never meant to be THE TRUTH. This is really meant to be, “Hey, by the way, if you just happen to live by these standards, it works pretty well.” It was never meant to be the one great truth of the universe that you must abide by.

— Richard Garriott

An awful lot of people get awfully exercised over the lore and legends of Britannia and the many failings of Richard Garriott’s stewardship thereof. Some of them spend their time in tortured ret-conning, trying to explain why the geography of the place kept changing from game to game, why its name was changed overnight from Sosaria to Britannia, or, even more inexplicably, why it suddenly turned into our own Earth for a little while there during the time of Ultima II. Others prefer to just complain about it, which is fair enough.

I have to say, though, that it’s hard for me to really care. For me, the Ultima series isn’t most interesting as the saga of Britannia, but rather as something more intimate. It’s the CRPG equivalent of the film Boyhood. As we play through the games we see its creator grow up, from the giddy kid who stuck supercomputers, space shuttles, and Star Wars in his fantasy games — because, hey, those things are all just as cool as Dungeons and Dragons to a nerdy teenager — to the more serious young man who used Ultima IV and, now, Ultima V to try to work out a philosophy for living. Taken as a whole, the series can be seen as a coming-of-age tale as well as a fantasy epic. Having reached a stage in my life where the former is more interesting than the latter, that’s how I prefer to see it anyway. Rather than talk about the Ages of Britannia, I prefer to talk about the ages of Richard Garriott.

What makes the process so gratifying is that the changes that Richard Garriott undergoes are, one senses, the changes that a good-hearted, thoughtful young man ought to undergo. Which is not to say that Garriott is perfect. Lord knows it’s easy enough to mock the sheer one-percenter excess of paying Russia a reputed $30 million to haul him into space for twelve days, and some of his public comments do rather suggest he may be lacking in the Virtue of Humility. But then, given how much his (alter) ego has been stroked over the years,[1]The classic hagiography of Garriott still has to be Shay Addams’s 1990 Official Book of Ultima. Here’s Garriott the teenage Lothario, deigning to allow some of his many girlfriends to sit with him while he programs his fantastic creations: “My girlfriends, who understood what was going on in those days and were a big part of my life, and who always showed up in the games, would sit right behind me in the same chair at my desk.” Resting her head on Garriott’s shoulder, she would “just sit there watching me program a few lines and test it, and watch the creation unfold.” And here’s Garriott the scholar, plumbing musty old tomes to come up with a magic system: “A full moon hovered over the skyline, casting a pale gold glow on the crinkled pages of the leather-bound tome as Garriott slowly thumbed through it at his desk. Magic was in the making, for his task was nothing less than to coin the language of magic that would be spoken by the mages and wizards of Ultima V. Planning to quickly ferret out a suitable synonym for poison and call it a night, he’d hauled the massive 11-language dictionary from the shelf hours ago. But so engrossed did he become with the subtle nuances and shades of meaning, so captivated by the alluring assortment of nouns and adjectives and verbs, that he sat over its faded pages long after choosing the Latin ‘noxius,’ from ‘noxa,’ to harm, and abbreviating it to ‘nox.'” it’s not surprising to find that Garriott regards himself as a bit of a special snowflake. Ironically, it wasn’t so much his real or imagined exceptionalism as it was the fact that he was so similar to most of his fans that allowed him to speak to them about ideas that would have caused their eyes to glaze over if they’d encountered them in a school textbook. Likewise, the story of the Richard Garriott whom we glimpse through his games is interesting because of its universality rather than its exceptionalism; it fascinates precisely because so many others have and continue to go through the same stages.

In Ultima IV, we saw his awakening to the idea that there are causes greater than himself, things out there worth believing in, and we saw his eagerness to shout his discoveries from every possible rooftop. This is the age of ideology — of sit-ins and marches, of Occupy Wall Street, of the Peace Corps and the Mormon missionary years. Teenagers and those in their immediate post-teenage years are natural zealots in everything from world politics to the kind of music they listen to (the latter, it must be said, having at least equal importance to the former to many of them).

Yet we must acknowledge that zealotry has a dark side; this is also the age of the Hitler Youth and the Jihad. Some never outgrow the age of ideology and zealotry, a situation with major consequences for the world we live in today. Thankfully, Richard Garriott isn’t one of these. Ultima V is the story of his coming to realize that society must be a negotiation, not a proclamation. “I kind of think of it as my statement against TV evangelists,” he says, “or any other group which would push their personal philosophical beliefs on anybody else.” The world of Ultima V is messier than Ultima IV‘s neat system of ethics can possibly begin to address, full of infinite shades of gray rather than clear blacks and whites. But the message of Ultima V is one we need perhaps even more now than we did in 1988. If only the worst we had to deal with today was television evangelists…

Garriott often refers to Ultima IV as the first Ultima with a plot, but that strikes me as an odd contention. If anything, there is less real story to it than the Ultimas that preceded it: be good, get stronger, and go find a McGuffin called the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom pretty much sums it up. (It’s of course entirely down to the first of these that Ultima IV is such a revolutionary game.) I sense a false conflation here of games with a plot with games that are somehow more worthwhile or socially relevant. “I’m writing stories,” he said during the late 1980s, “stories with some socially significant meaning, or at least some emotional interest.” But if we strip away the value judgments that seem to be confusing the issue, we’re actually left with Ultima V, the first Ultima whose premise can’t be summed up in a single sentence, as the real first Ultima with a plot. In fact, I think we might just need a few paragraphs to do the job.

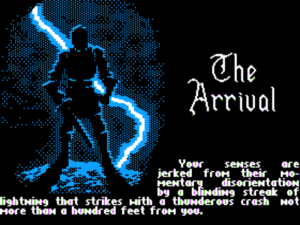

Thanks to Denis Loubet, Origin’s newly installed artist, Ultima V looks better than the previous games in the series even on a graphically limited platform like the Apple II.

So, after you became an Avatar of Virtue through the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom at the bottom of Ultima IV‘s final dungeon, you were rewarded for your efforts by being sent back to boring old twentieth-century Earth to, as the ending text so famously put it, “live there as an example to thy people.” In Britannia, the Council of Wizards raised the Codex to the surface by essentially turning the volcano that housed it inside-out, creating a mountain with a shrine to the Codex on its top. But this process created a huge underground void, an Underworld as big as Britannia’s surface that among other things allows Ultima V to make the claim that it’s fully twice as big as its predecessor. (No, the proportions of one volcano, no matter how immense, don’t quite add up to the whole of Britannia, but just roll with it, okay?)

Everything was still going pretty well in Britannia, so Lord British decided he’d like to embark on an adventure of his own instead of always sending others off to face danger. He got a party together, and they entered the new Underworld on a mission of exploration. Bad idea. He and his party were all killed or captured, only one scribe escaping back to the surface with a tale of horrors in the depths. “And this,” I can just hear Lord British saying, “is why I should have continued to let others do the adventuring for me…”

It happens that Lord British left one Lord Blackthorn as his regent. Now, with Lord British presumed dead, it looks like the post will become permanent. That’s bad news because Blackthorn, concerned that not enough people in Britannia are “striving to uphold the virtues,” has instituted a Code of Virtue to force them to do so.

- Thou shalt not lie, or thou shalt lose thy tongue.

- Thou shalt help those in need, or thou shalt suffer the same need.

- Thou shalt fight to the death if challenged, or thou shalt be banished as a coward.

- Thou shalt confess to thy crime and suffer its just punishment, or thou shalt be put to death.

- Thou shalt donate half of thy income to charity, or thou shalt have no income.

- If thou dost lose thine own honor, thou shalt take thine own life.

- Thou shalt enforce the laws of virtue, or thou shalt die as a heretic.

- Thou shalt humble thyself to thy superiors, or thou shalt suffer their wrath.

A number of your old companions from Ultima IV, opposing this Britannic version of the Spanish Inquisition, have become outlaws against the crown. They arrange to transport you back to Britannia from Earth to hopefully save the day. Garriott:

So, where Ultima IV was fairly black-and-white — I mean good guys are good guys and bad guys are bad guys — Ultima V unfolds in a gray area. Lots of characters try convincing you that Blackthorn is doing things just right, some say he’s an evil force, and others realize he’s wrong but are taking advantage of the situation for personal profit and are willing to fight anyone who opposes Blackthorn. You now have to operate more or less like a Robin Hood-style outlaw, working against the system but from within the system, which you must bring down philosophically as well by convincing key people in the government that they are wrong about Blackthorn.

Now we can better understand where the plot is really going. Crazily elaborate by previous Ultima standards though it is, the part of the backstory involving Lord British’s trip to the Underworld is mainly there to get him out of the picture for a while so Garriott can tell the story he wants to tell. “Rescuing Lord British in Ultima V is not really the focus of the game,” Garriott admits. “It’s just the final physical activity you have to do, like recovering the Codex in Ultima IV. It is how you do it that’s important.” Garriott wants to turn Britannia, all sweetness and light in Ultima IV (albeit with something of a monster-infestation problem), into a place every bit as horrifying in its own way as the Underworld. And, more accepting of shades of gray though he may have become, he isn’t quite willing to make Lord British — i.e., himself — responsible for that.

If all this isn’t enough plot for you, there’s also the story of one Captain John, whose ship got sucked into the Underworld by a massive whirlpool. There he and his crew stumbled upon one of those Things of Which Man Was Not Meant to Know, which drove him insane and caused him to murder his entire crew, then unleashed the three Shadowlords upon Britannia: personifications of Falsehood, Hatred, and Cowardice. It does seem that you, noble Avatar, have your work cut out for you.

It’s a much clunkier setup in many ways than that of Ultima IV. A big part of that game’s genius is to equate as closely as possible the you sitting in front of the monitor screen with the you who roams the byways of Britannia behind it. Opening with a personality test to assess what kind of a character you are, Ultima IV closes with that aforementioned exhortation to “live as an example to thy people” — an exhortation toward personal self-improvement that hundreds of thousands of impressionable players took with considerable seriousness.

All that formal elegance gets swept away in Ultima V. The newer game does open with a personality test almost identical to the one in Ultima IV, but it’s here this time not to serve any larger thematic goal so much as because, hey, this is an Ultima, and Ultimas are now expected to open with a personality test. Instead of a very personal journey of self-improvement, this time around you’re embarking on just another Epic Fantasy Saga™, of which games, not to mention novels and movies, certainly have no shortage. Garriott’s insistence that it must always be the same person who stars in each successive Ultima is a little strange. It seems that, just as every successive Ultima had to have a personality test, he reckoned that fan service demanded each game star the selfsame Avatar from the previous.

The gypsy and her personality test are back, but the sequence has a darker tone now, as suits the shift in mood of the game as a whole.

But whatever its disadvantages, Ultima V‘s new emphasis on novelistic plotting allows Garriott to explore his shades of gray in ways that the stark simplicity of Ultima IV‘s premise did not. The world is complicated and messy, he seems to be saying, and to reflect that complication and messiness Ultima has to go that way too. Nowhere is his dawning maturity more marked than in the character of Blackthorn, the villain of the piece.

CRPG villains had heretofore been an homogeneous rogue’s gallery of cackling witches and warlocks, doing evil because… well, because they were evil. In tabletop Dungeons and Dragons, the genre’s primary inspiration, every character chooses an alignment — Good, Neutral, or Evil — to almost literally wear on her sleeve. It’s convenient, allowing as it does good to always be clearly good and those hordes of monsters the good are killing clearly evil and thus deserving of their fate. Yet one hardly knows where to begin to describe what an artificial take on the world it is. How many people who do evil — even the real human monsters — actually believe that they are evil? The real world is not a battleground of absolute Good versus absolute Evil, but a mishmash of often competing ideas and values, each honestly certain of its own claim to the mantle of Good. Our more sophisticated fictions — I’m tempted here to say adult fictions — recognize this truth and use it, both to drive their drama and, hopefully, to make us think. Ultima V became the first CRPG to do the same, thanks largely to the character of Blackthorn.

Blackthorn is not your typical cackling villain. As Garriott emphasizes, “his intentions are really very good.” Setting aside for a moment the message-making that became so important to Garriott beginning with Ultima IV, Ultima V‘s more nuanced approach to villainous psychology makes it a more compelling drama on its own terms. The fact that Blackthorn is earnestly trying to do good, according to his own definition of same, makes him a far more interesting character than any of the cacklers. Speaking from the perspective of a storyteller on the lookout for interesting stories, Garriott notes that a similar certainty of their own goodness was the “best part” about the Moral Majority who were dominating so much of the political discourse in the United States at the time that he was writing Ultima V.

And yet, Garriott acknowledges, legislating morality is according to his own system of values “just the wrong thing to do.” He has held fast to this belief in the years since Ultima V, proving more than willing to put his money where his mouth is. The version of Richard Garriott known to the modern political establishment is very different from the Richard Garriott who’s so well known to nerd culture. When not playing at being a Medieval monarch or an astronaut, he’s a significant donor and fundraiser for the Democratic party as well as for organizations like Planned Parenthood, a persistent thorn in the side of those people, of which there are many in his beloved Texas, who would turn their personal morality into law.

As for Blackthorn, his evil — if, duly remembering that we’re now in a world of shades of gray, evil you consider it to be — is far more insidious and dangerous than the cackling stripe because it presents itself in the guise of simple good sense and practicality. A long-acknowledged truth in politics is that the people you really need to win over to take control of a country are the great middle, the proverbial insurance underwriters and shop owners — one well-known ideologue liked to call them the bourgeois — who form the economic bedrock of any developed nation. If you can present your message in the right guise, such people will often make shocking ethical concessions in the name of safety and economic stability. As the old parable goes, Mussolini may have been a monster, but he was a monster who made the trains run on time — and that counts for a hell of a lot with people. More recently, my fellow Americans have been largely willing to overlook systematic violations of the allegedly fundamental right of habeas corpus, not to mention unprecedented warrantless government spying, in the same spirit. The citizens of Britannia are no different. “In a society that is very repressive like this,” Garriott notes, “many good things can happen. Crime is going down. Certain kinds of businesses [military-industrial complex? surveillance-industrial complex?] are going to flourish.”

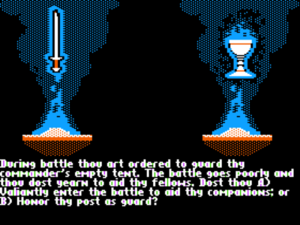

The ethics of Ultima IV are easy. Really, how hard is it to decide whether it’s ethical to cheat a blind old shopkeeper of the money she’s due? This time around, Garriott doesn’t let us off so easy. He puts us through the ethical wringer every chance he gets, showing us that sometimes there is no clear-cut ethical choice, only… yes, you guessed it, infinite shades of gray. Just like antagonists, ethical dilemmas become more interesting when they pick up a little nuance. Maybe they become a little too interesting; Garriott proves willing to go to some uncomfortable places in Ultima V, places few big commercial CRPGs of today would dare to tread.

At one point, Blackthorn captures one of your boon companions in Virtue from Ultima IV. He binds him to a table beneath a razor-sharp pendulum lifted out of Edgar Allan Poe. Betray the plans of your burgeoning resistance movement, Blackthorn tells you, and he will free your friend. Refuse and… well, let’s just say that soon there will be two of him. Scenes like this are familiar fare in movies and television, culminating always in a last-second rescue just before blade bites flesh. In this case, however, there will be no rescue. Do you watch your dear friend die or do you betray everything he stands for? If you let him die, Ultima V erases Iolo entirely from the disk, to deny you the hope of resurrecting him and remind you that some choices really are final.

At another point, you meet a character who holds a vital piece of information, but he’ll part with it only if you exorcise his personal grudge by turning in one of your own friends to Blackthorn’s Inquisition. Personal loyalty or the greater good? Think fast, now! Which will it be? Garriott:

There is no other solution. I agree it was a dirty trick, having to turn in one of the good guys to get information. Now, admittedly, the game never really goes and lynches the guy, but you must presume that is the ramification of what you have done. That is a tough personal thing that I put in there, not because I knew the answer myself, but because I knew it would be a tough decision.

The most notoriously memorable of all Ultima V‘s ethical quandaries, still as shocking when you first encounter it today as it was back in 1988, is the room of the children. Like so much in game design, it arose from the technical affordances (or lack thereof) of the Ultima V engine. Unlike the surface of Britannia, dungeons can contain only monsters, not characters capable of talking to you. Looking for something interesting to put in one of the many dungeons, Garriott stumbled across the tiles used to represent children in Britannia’s towns and castles.

When you walk into the room of the children, they’re trapped in jail cells. Free them by means of a button on the wall, and they prove to be brainwashed; they start to attack your party. You need to get through the room — i.e., through the children — in order to set matters right in Britannia. Once again it’s a horrid question of the greater good — or smaller evil? Garriott:

Well, I thought, that is an interesting little problem, isn’t it? Because I knew darn well that the game doesn’t care whether you kill them or whether you walk away. It didn’t matter, but I knew it would bring up a psychological image in your mind, an image that was in my mind — and any conflict you bring up in anybody’s mind is beneficial. It means a person has to think about it.

In this situation, Garriott — or, perhaps better said, the game engine — thankfully did allow some alternatives to the stark dichotomy of killing children or letting Britannia go to ruin. The clever player might magically charm the children and order them out of the room, or put them to sleep (no, not in that sense!) and just walk past them.

The room nevertheless caused considerable discord within Origin. Alerted by a play-tester whom Richard Garriott calls “a religious fundamentalist,” Robert Garriott, doubtless thinking of Origin’s previous run-ins with the anti-Dungeons and Dragons contingent, demanded in no uncertain terms that his little brother remove the room. When Richard refused, Robert enlisted their parents to the cause; they also asked why he couldn’t be reasonable and just remove this “little room.” “Why,” they asked, “are you bothering to fight for this so much?”

And I said, “Because you guys are missing the point. You are now trying to tell me what I can do artistically — about something that is, in my opinion, not the issue you think it is. If it was something explicitly racist or sexist or promoting child abuse, I could stand being censored. But if it is something that provoked an emotional response from one individual, I say I have proven the success of the room. The fact that you guys are fighting me over this makes me even more sure I should not remove that room from the game.”

And so it remained. Much to Robert’s relief, the room of the children attracted little attention in the trade press, and none at all from the sort of quarters he had feared. Buried as it is without comment deep within an absolutely massive game, those who might be inclined toward outrage were presumably just never aware of its existence.

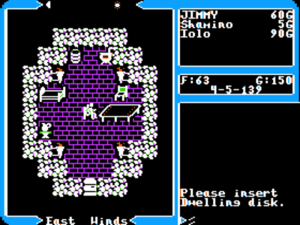

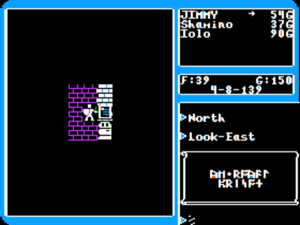

Ultima V‘s screen layout and interface appear superficially all but identical to its predecessor, but a second glance reveals a new depth to the interaction. Note that I’m sitting in a chair here. In addition to the chair, the bed, the torches, the barrel, and the stone are all implemented as objects with which I can interact.

Having now spent almost 4000 words discussing the greater themes of Ultima V, I have to acknowledge that, just as with its predecessor, you spend a relatively small proportion of your time directly engaging with those themes when actually playing. Whatever else it is, this is still a conventional CRPG with all the expected mechanics of leveling-up and monster-killing. As usual for the series, its code is built on the base of its predecessor’s, its screen layout and its alphabet soup of single-letter commands largely the same. Ditto its three scales of interaction, with the abstract wilderness map blowing up into more detailed towns and still more detailed, first-person dungeons. The graphics have been noticeably improved even on the graphically limited 8-bit machines, thanks not least to Denis Loubet’s involvement as Origin’s first full-time artist, and the sound has been upgraded on suitably equipped machines to depict the splashing of water in fountains and the chiming of clocks on walls. Still, this is very much an Ultima in the tradition stretching all the way back to Akalabeth; anyone who’s played an earlier game in the series will feel immediately comfortable with this one.

That means that all the other things that Ultima fans had long since come to expect are still here, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. The hilariously awful faux-Elizabethan diction, for instance, is still present and accounted for. (One of my favorite examples this time out is a father telling his son he needs an attitude adjustment, a slang phrase very en vogue at the time of Ultima V‘s release courtesy of countless harried sitcom parents: “Thou shalt take a year off from magic, Mondain, to improve thy attitudes.”) And there’s still the sense of an earnest but not yet hugely well-traveled young man — physically or intellectually — punching a bit above his weight in trying to create a new world out of whole cloth. For instance, with Garriott apparently starting to feel uncomfortable with the whole divine-rule-of-kings thing, Britannia has now become a republic with an uncanny resemblance to the only republic with which Garriott is at all familiar, that of the United States; Lord British, naturally, sits in for the President. Even the story of the government’s founding mirrors that of the American Constitutional Convention. Tolkienesque world-building, needless to say, this is not.

For all its additional complexities of theme and plot, Ultima V actually exhibits more continuity with its predecessor than any earlier Ultima. For the first time in an Ultima, it’s possible to import your character from the previous game, an innovation dating back to the second Wizardry game that most other CRPG series had long embraced. And the overland map of Britannia in Ultima V is, apart from that new volcano that popped up where a dungeon used to be, almost exactly the same as that of Ultima IV.

At the same time, however, Ultima V is a vastly bigger and even more ambitious game than its predecessor. Positioned in the same places on the overland map though they are, all of the towns, castles, and dungeons have been extensively remodeled and expanded during the (Britannic) years that have passed between the two games. And if that’s not enough space for adventure, there’s of course also the huge Underworld that’s been added. The magic system has been revamped and better systemized, now sporting almost twice as many spells — almost fifty in total — that are divided into eight “circles” of power. The parser-based conversation system, while superficially unchanged from that of Ultima IV, now understands much, much more, and delivers more text back in response to every query.

But the heart of Ultima V‘s ambition is not in the sprawl but in the details. Ultima V‘s Britannia must still stand as one of the more impressive virtual worlds ever made. Many of its complexities are seldom seen even in games of today. To see them in a game that runs in 64 K of memory feels nothing short of miraculous. Every object in every room is now an object of its own in the programmatic as well as visual sense, one that can be realistically manipulated: torches can be taken off walls, chairs can be sat in, harpsichords can be played. Just as impressive is the game’s implementation of time. As you play, not only does day cycle to night and back again, but the seasons change, the fields filling with crops over the course of the growing season and then appearing bare and forlorn again when winter comes. Unbeknownst to many players, even the cycles of the heavens are scrupulously modeled, two moons and eight other planets moving across the sky, each according to its own orbit. Every five and a half years comes a full planetary alignment, which you can witness if you happen to look through a telescope at just the right instant. This Britannia is a land bursting with secrets and wonders, truly an unprecedented achievement in its day in virtual world-building.

In keeping with the new focus on temporal change, characters now follow daily schedules instead of standing endlessly in one spot. Consider Jeremy, who lives and works in the inn in the city of Yew. He gets up from his back-room lodgings at 9:00 each morning to go to the prison to visit his brother, who’s been incarcerated there under Blackthorn’s heresy laws. He gets back to the inn in time for the lunch rush, and spends the whole day working in the kitchen. After closing time, he visits his brother once more, then returns to his room to sleep. Meanwhile the entire town is following similar patterns; virtually everyone stops at Jeremy’s inn for a bite to eat and a bit of gossip at some point during the day. Guard shifts change; drawbridges and portcullises go up and down; shops open and close. Coupled with the richer conversations, it’s enough to make the inhabitants of the town feel like real people living real lives rather than conversation vending machines waiting for the Avatar to step up and trigger a clue, a joke, or a non sequitur.

Indeed, this version of Britannia as a whole is a less artificial place than Ultima IV‘s. While all of the towns from that game remain, each still corresponding to a Virtue, the correspondence is less neat. Garriott:

When you walk into a town it should look like a bustling Medieval village, with all the normal kinds of things you’d expect to find in a town, but there are only six characters that you have a chance to meet and talk to. These six characters don’t tell you straight out that “Moonglow is the city of Honesty,” for example. It’s not like honesty awards are plastered everywhere. It’s more that because of the nature of commerce in this town, because of what is important to these people, honesty is a consistent trait. You might hear, “By the way, everyone around here is pretty honest. It’s one of the things that we pride ourselves on around here.” Like “everything is bigger in Texas,” that kind of thing.

There are welcome signs that Garriott and his development team have themselves taken note of many of the things I complained about in my article on Ultima IV — those things that, at least in my contrarian opinion, made that game a fascinating one to talk about but not always a terribly compelling one to play. Major steps have been taken to reduce the tedium factor. As Garriott attests above, the non-player characters in the towns and castles are among a few things in Ultima V that have wisely been reduced in number in comparison to its predecessor. Instead of having to lawnmower through dozens of pointless conversations in every town, you’re left with a smaller number of personalities who fit with the world and who are actually interesting to speak to — in other words, no more Paul and Linda McCartney wandering around quoting lyrics from their latest album. The pain of the endless combat in Ultima IV is similarly reduced, and for similar reasons. There are far fewer monsters roaming the Britannic countryside this time around (another result of Blackthorn’s law-and-order policies?), and when you do have to fight you’ll find yourself dropped into a more complex combat engine with more tactical dimensions. The dungeons, meanwhile, are stuffed with interesting scripted encounters — perhaps too interesting at times, like that room of the children — rather than endless wandering monsters. Mixing reagents for spells is still incredibly tedious, and Garriott has devised one entirely new recipe for aggravation, a runic alphabet used by most of the printed materials you find in the game that must be laboriously decoded, letter by letter, from a chart in the manual. Nevertheless, on balance he has given us a much more varied, much less repetitive experience.

But alas, many of Ultima IV‘s more intractable design problems do remain. Solving Ultima V is still a matter of running down long chains of clues, most of them to be found in only one place in this vast world, and often deliberately squirreled away in its most obscure corners at that. Even if you can muster the doggedness required to see it through, you’re all but guaranteed to be completely stymied at at least one point in your journeys, missing a clue and utterly unsure where to find it in the whole of Britannia. The cycles of time only add to the difficulty; now you must often not only find the right character to get each clue, but also find the right character at the right time. Ultima V is in the opinion of many the most difficult Ultima ever made, a game that’s willing to place staggering demands on its player even by the standards of its own day, much less our own. This is a game that plops you down at its beginning, weak and poorly equipped, in a little cottage somewhere in Britannia — you have no idea where. Your guidance consists of a simple, “Okay, go save the world!” The Ultima series has never been known for coddling its players, but this is approaching the ridiculous.

I think we can find some clues as to why Ultima V is the way it is in Garriott’s development methodology. He has always built his games from the bottom up, starting with the technical underpinnings (the tile-graphics engine, etc.), then creating a world simulated in whatever depth that technology allows. Only at the end does he add the stuff that makes his world into a proper game. Ironically given that Ultima became the CRPG series famed for its plots, themes, and ideas, said plots, themes, and ideas came in only “very, very late in the development” of each game. The structure of play arises directly from the affordances of the simulated world. A classic example, often cited by Garriott, is that of the harpsichord in Ultima V. After adding it on a lark during the world-building phase, it was natural during the final design phase to give it some relevance to the player’s larger goals. So, he made playing it open up a secret panel; therein lies an item vital to winning the game. Garriott:

[This approach] makes a great deal of sense to me. The worst example of this is exactly the wrong way to design your game. If I say, “Here’s a story, pick any book at random, make me a game that does that,” it won’t work. The reason why is because that story is not written with “Is the technology feasible?” in mind. By definition it will not be as competitive as my game is because I have chosen specific story elements that the technology shows off particularly well. It required little, if any, extra work, and it works well with all the other elements that can exist. It is designed to adhere to the reality that you can pull off technologically. By definition, it fits within the reality of Britannia.

And every time a new management person comes in and says, “Richard, you’re doing it all wrong,” I make my case, and eventually they either give up on me or become a convert.

It’s interesting to note that Garriott’s process is the exact opposite of that employed by a designer like, say, Sid Meier, who always comes up with the fictional premise first and only then figures out the layers of technology, simulation, and gameplay that would best enable it. While I’m sure that Garriott is correct in noting how his own approach keeps a design within the bounds of technical feasibility, the obvious danger it brings is that of making the actual game almost a footnote to the technology and, in the case of the Ultima games in particular, to the elaborate world-building. A couple of other landmark CRPGs were released during 1988 (fodder for future articles) whose designers placed more and earlier emphasis on the paths their players would take through their worlds. In contrast to the fragile string of pearls that is Ultima V, these games offer a tapestry of possibilities. Later CRPGs, at least the well-designed ones, followed their lead, bringing to an end that needle-in-a-haystack feeling every 1980s Ultima player knows so well. Among those later CRPGs would be the later Ultimas, thanks not least to some new voices at Origin who would begin to work with Garriott on the designs as well as the technology of his creations. If you’re dismayed by my contrarian take on the series thus far, know that we’re getting ever closer to an Ultima that even a solubility-focused old curmudgeon like me can enjoy as much as he admires. For now, suffice to say that there’s enough to admire in Ultima V as a world not to belabor any more its failings as a game design.

That said, there are other entirely defensible reasons that Ultima V doesn’t hold quite the same status in gaming lore as its illustrious predecessor. Ultima IV was the great leap, a revolutionary experiment for its creator and for its genre. Ultima V, on the other hand, is evolution in action. That evolution brings with it hugely welcome new depth and nuance, but the fact remains that it could never shock and delight like its predecessors; people had now come to expect this sort of thing from an Ultima. Certainly you don’t find for Ultima V anything like the rich, oft-quoted creation story of Ultima IV, the story of how Garriott first came to think about the messages he was putting into the world. And that’s fine because his eyes were already open when he turned to Ultima V. What more is there to say?

Nor did Ultima V have quite the same immediate impact on its fans’ hearts and minds as did its predecessor. Ultima V‘s message is so much messier, and, Garriott himself now being a little older, is less tuned to the sensibilities of the many teenagers, as craving of moral absolutism as ever, who played it when it first appeared. Far better for them the straightforward Virtues of the Avatar. One can only hope that the message of this game, subtler and deeper and wiser, had its effect over time.

Whatever you do, don’t let my contrariness about some of its aspects distract from Ultima V‘s bravest quality, its willingness to engage with shades of gray in a genre founded on black and white. The game never, ever veers from its mission of demonstrating that sometimes Virtue really must be its own reward, not even when it comes to the traditional moment of CRPG triumph. When you finally rescue Lord British and save Britannia at the end of Ultima V, you’re ignominiously returned to Earth. In the anticlimax, you return to your apartment to find it broken into, your things stolen. Sigh. Hope you had insurance. It’s a messy old world out there, on Earth as on Britannia.

(Sources are listed in the preceding article. Ultima V is available from GOG.com in a collection with its predecessor and sequel.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The classic hagiography of Garriott still has to be Shay Addams’s 1990 Official Book of Ultima. Here’s Garriott the teenage Lothario, deigning to allow some of his many girlfriends to sit with him while he programs his fantastic creations: “My girlfriends, who understood what was going on in those days and were a big part of my life, and who always showed up in the games, would sit right behind me in the same chair at my desk.” Resting her head on Garriott’s shoulder, she would “just sit there watching me program a few lines and test it, and watch the creation unfold.” And here’s Garriott the scholar, plumbing musty old tomes to come up with a magic system: “A full moon hovered over the skyline, casting a pale gold glow on the crinkled pages of the leather-bound tome as Garriott slowly thumbed through it at his desk. Magic was in the making, for his task was nothing less than to coin the language of magic that would be spoken by the mages and wizards of Ultima V. Planning to quickly ferret out a suitable synonym for poison and call it a night, he’d hauled the massive 11-language dictionary from the shelf hours ago. But so engrossed did he become with the subtle nuances and shades of meaning, so captivated by the alluring assortment of nouns and adjectives and verbs, that he sat over its faded pages long after choosing the Latin ‘noxius,’ from ‘noxa,’ to harm, and abbreviating it to ‘nox.'” |

|---|

Pedro Timóteo

February 12, 2016 at 6:17 pm

Absolutely fantastic. I loved reading it, and now I feel I must *really* finish Ultima V once and for all (I’ve started playing it several times, but since I only found out about it after playing VI, the engine, and especially the annoyances you mention, like mixing reagents and deciphering the runes, have always stood in the way).

I’d also like to mention the soundtrack. Most of this I only played under emulation (back then I just played the PC version, and saw the Amiga version at a friend’s), but U5 has a great soundtrack on the Apple II with Mockingboard sound cards (supported by emulators such as AppleWin), including the first appearance of “Stones”. It’s also significant for being one of the very, very few games to natively support the Commodore 128, having the entire soundtrack on that system, but no music at all on the C64. And on the Amiga it has only a single track playing through the entire game, which does not appear in any other version, that sounds like a ballad (and very sad) version of Metallica’s “One” (the beginnings of both are virtually identical).

These days there’s a patch to add MIDI music to the PC version (it works with the one from GOG, under DOSBox), which I’d recommend to anyone playing it, although it isn’t perfect, IMO; the Ultima V theme (that plays when the game boots up) is missing the drums from the Apple II and C128 versions, and the Amiga theme (that the patch adds to character creation here), while still good, sounds, I think, a lot less haunting than the original version on the Amiga.

TsuDhoNimh

February 12, 2016 at 6:30 pm

I remember playing this game when I was passed a pirated copy (with photocopied manual) from a friend. I played obsessively for about two months, taking many pages notes, interrogating everyone I could find, and having fun building my character and allies. I think I got about 75% of the way through the game before losing interest, probably getting stuck on one of those obscure clues that I could never find in the age before everything was available on a gaming wiki.

A side-effect of playing this game was that part of my circle of friends in high school had memorized the runic alphabet in the manual. We took advantage of this newfound skill to pass coded messages in class that (when we were caught) left out teachers scratching their heads.

Josh Scherr

February 12, 2016 at 6:46 pm

Thanks for this – as always, I love the depth and insight you put into these articles. Ultima V is probably still my favorite of all the Ultimas I played (never played 8 or 9), largely because of the nuance added to the story (such as it was) and the depth to the world. Day/night! People with schedules!

It happened to come out over my spring break in high school, so I pretty much spent the entire 5 days playing the entire thing start to finish. A week later, Egghead Software (our local Babbages equivalent) was hosting a software expo with Garriott in attendance. I brought my cloth map for him to sign and when he asked me what I thought of the game, I told him I thought it was great. He paused and said “Was…? You finished it already? That was fast!” Made an impression on my 16 year-old self.

Steven Marsh

February 12, 2016 at 7:02 pm

I wouldn’t want to re-experience it, but one of the things I recall from living the Apple II era the first time was the physicality of disk access. In Ultima V, when you entered a Town or Dungeon, you needed to put in the Town or Dungeon disks, and the disk drive would ka-chunk, ka-chunk, and then you’d see the results.

.

I remember those extra moments being very tense in games. I especially remember it from the Infocom games; when the disk started ka-chunking significantly, I knew that I was either doing something interesting or possibly even stumbling onto a solution.

.

I prefer the instant-access emulator world, but sometimes I long for the times when traveling across the Ultima world would pause constantly as various new chunks loaded in memory.

Jayle Enn

February 12, 2016 at 7:10 pm

It was a godsend when Dad got a second drive for the IIc. I could put the Land disk in one, and preemptively swap town/castle/dungeon disks in the other. Sped things up, but you still got that ominous drive chatter.

Jimmy Maher

February 13, 2016 at 8:06 am

I think many of us have the same memory with Infocom games in particular. It’s one aspect of the old-school gaming experience that really can’t be conveyed via emulation. “Physicality” is a great word for it.

Steve

February 15, 2016 at 12:33 am

This is one reason I really appreciate emulators with a high quality implementation of drive sound emulation. It doesn’t quite recapture the “feel” of swapping disks into real drives, but it recaptures that sense of “something’s happening” when the drive suddenly fires up for an extended load.

Unfortunately this feature is fairly rare. The Apple ][ emulator Virtual ][ for Mac OS X does this very nicely, for example, whereas AppleWin doesn’t currently support drive sound emulation at all.

Rob Lyons

January 24, 2018 at 3:09 am

I’m adding this comment a few years after the fact, but even though Apple II machines outside of elementary school was a rare sight by the time I would have found this, being a few generations past it’s prime; I can still understand that “physicality” you mention. Even on much further reaching systems, such as the Sega Dreamcast those of us later would experience this.

I can still easily recall the exact sound of the Dreamcast’s GDROM drive when it would start accessing the disc while flying in the overworld in Skies of Arcadia , cluing me into the fact that I am about to have a random enemy encounter.

Many years later, I would play a port of this game, and that was no longer there. I went back to my Dreamcast version.

Jayle Enn

February 12, 2016 at 7:08 pm

I played the Apple II version of this for literally two years and some, largely because I was confused by the copy protection bit with the harpsichord in a certain room.

It’s possible (or at least it was) to evade the pendulum event. I did t largely by abusing the way monsters behave when your entire party is invisible, and the magic carpet.

The dungeon room with the kids was odd, but when they attacked I figured they were evil gnomes and fought back.

Steven Marsh

February 12, 2016 at 7:19 pm

Oh, and I should also note that Iolo shows up in future Ultimas, so I guess we know how THAT moral conundrum played out canonically.

Jimmy Maher

February 13, 2016 at 8:06 am

Or Origin/Garriott just forgot about it. :) See my first paragraph…

Steven Marsh

February 13, 2016 at 6:41 pm

Fair enough. :-)

samsinx

February 12, 2016 at 8:50 pm

U5 was a game I played for months and finished in my early teens without any clues. Like you said, it was by far the most difficult playable Ultima (unlike say, U8…) I can’t imagine having the patience to finish it today.

That said, I really think it’s the second best single-player Ultima game (U7 1&2 yes was better.) And it had the best combat of the series. After U5, combat seemed increasingly less important with each sequel.

Jimmy Maher

February 13, 2016 at 8:11 am

I think I like the later games more partially because there *isn’t* so much combat. (I believe it’s possible to finish Ultima VI almost without fighting at all.) I enjoy combat in games that make it their focus and lavish some care on its implementation, but it always just feels like a distraction and annoyance to me in Ultima. I agree, though, that Ultima V comes closest to making it interesting enough to justify its existence.

Pedro Timóteo

February 13, 2016 at 10:33 am

Weird, I remember Ultima VI as being the Ultima where combat took the longest time, and where equipment mattered the most. It was also the first Ultima, I think, to make enemies drop their full equipment when dead (before that, you’d typically just buy it in stores), which meant that after combat you’d have to go through all the dead bodies to decide what to get and what to leave — so, counting that, each battle typically took a looong time.

IMO, it was only by Ultima VII that combat became an afterthought, which, like you, I didn’t mind at all… but then it became basic but time-consuming and repetitive in VIII and IX (not helped by the fact that there’s no party in those games).

Jimmy Maher

February 13, 2016 at 10:51 am

I could be mis-remembering. Update when we get there. ;)

Pedro Timóteo

February 14, 2016 at 10:50 am

About Ultima VII, I’ve been thinking about / remembering it, and combat isn’t probably really an afterthought like I said above. It’s just that it happens quickly and (mostly) automatically, and the focus isn’t really what you do during combat, but how you have prepared for it. It’s stlil important to:

1- level up your characters

2- find different trainers around the world to increase your characters’ stats (using “training points” that you get when levelling)

3- equip your characters as best as you can — and, besides what different stores sell (and at different prices), there’s a lot of unique equipment to find in the game

4- choose AI tactics for each character (e.g. attack closest enemy, attack weakest, attack strongest, protect weakest party member, prefer ranged attacks, etc.)

So, as you see, it’s not as trivial as it sounds; it’s just that it happens quickly and in real time, instead of being turn-based with you controlling every character manually. (It’s also skewed in favor of the player, so that if you’re caring even just a little about the 4 points above, you’ll probably win every time — they probably wanted to prevent player complaints like “what? I died 2 seconds after beginning combat? this game sucks!” — but because of it, it may feel too easy.)

Nate

February 13, 2016 at 7:30 pm

Really great article as usual. I’ve never played Ultima, but I’m saving up all these games for my days in the retirement home like old people today with their crosswords. Just me, a CRT, a floppy drive, and all these worlds. :-)

“overlook systematic violations” sounds odd to me. Do you mean “routine”? “Frequent”? Maybe “systemic”?

“Warrantless” is not hyphenated

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2016 at 8:14 am

Although your suggestions would work, I think systematic does work here as well: “Having, showing, or involving a system, method, or plan.”

My spellchecker doesn’t like “warrantless,” but I’ll take your work for it. ;)

Sniffnoy

February 13, 2016 at 9:28 pm

I’m confused by this bit and the quote that follows it:

I haven’t played the game, but going by the quote, it sounds like there *is* still a single city for every virtue, it’s just less blatant. I’m confused; would you mind clarifying?

By the way, some factual nitpicking: Mussolini did not, in fact, make the trains run on time. Which doesn’t affect the larger point (hence why I labeled this nitpicking), but I thought it was worth pointing out.

(Meanwhile, some proofreading: Blackthorne -> Blackthorn, ringer -> wringer,

Jimmy Maher

February 14, 2016 at 8:21 am

Yeah, that wasn’t written very well. Hopefully it’s clearer now.

I was more concerned with the legend/parable than the historical facts in the case of Mussolini, so, while the Snopes article is interesting, I think I’m going to leave mine alone. :)

Vince

September 12, 2023 at 8:28 am

I’m writing in 2023 a couple of days after reading of an Italian bar owner that prints Mussolini’s picture in the receipts of his establishment, because “he appreciates what good he did” (glossing over trivialities like racial laws, loss of freedom, countless people sent to their death in the most disastrous war Italy ever fought).

It really doesn’t matter whether the “he made trains run on time” is true or not, it exemplifies the sentiment of many people, even today, ready to justify almost anything in exchange for what they think will benefit them.

flowmotion

February 14, 2016 at 9:15 pm

Back in the 1980s, I don’t recall many people caring about “continuity” or “canon”. Every television show hit the reset button at the end of the episode, and you had series like James Bond where they cared little about continuity. Movies like Star Wars got you right into the action without having to explain what the characters were like when they were seven years old. Even nerd fare Doctor Who had like four different “Origins of the Daleks” stories and left the whole Time Lord business deliberately vague.

I think the obsession over canon is something from comic books that spread to the popular culture through Hollywood. Suddenly every single movie has to include an origin story. We now no longer can have a James Bond or Captain Kirk without learning how they became Bond/Kirk.

In any case, I was pretty darn nerdy, and it never bothered me for a second that Sosaria changed to Britannia, and the map changed every game. I played I, II, and III, and I completed Ultima IV. (Or almost completed, I didn’t have the final clue, and wasn’t intending to replay the final dungeon after dying many times.) I have always heard great things about V, but by the time it came out I was simply too busy with life to devote another hundred hours to Lord British.

Victor Gijsbers

February 15, 2016 at 10:24 am

The obsession over canon or ‘lore’ is also, I think, a result of the influence of the most lore-obsessed author of them all, J.R.R. Tolkien. Generations of fantasy writers grew up with the idea that having a coherent background world with a millenia long history, artificial languages and intricate cultures was both a necessary and a sufficient condition for a great fantasy ‘epic’.

The Bandsaw Vigilante

October 9, 2016 at 12:15 am

Agreed. People have gotten too preoccupied with the “canon” label itself as if it’s something that needs to be used or applied or defined before anything else can be done, or as if nothing really counts until this magic incantation is invoked, and turns it into a real live boy.

But that’s ascribing far too much power and importance to the word. It’s nothing more than a convenient description. It’s a shorthand label for referring to the core work in the franchise.

I think there are two things responsible for infecting fandom with their modern obsession with “canon” as something overarchingly urgent. One was Richard Arnold’s approach to Star Trek canon and tie-ins in the TNG era, his judgmental and exclusionistic view. He was pretty much the one who popularized the term “canon” in the first place — it existed going back to Sherlock Holmes fandom, of course, but I don’t remember sci-fi fans making use of the term or being all that obsessed with the canon status of a work until the ’90s.

The other thing that promoted fandom’s unhealthy and disproportionate obsession with canon was Lucasfilm Licensing’s approach to the Star Wars Expanded Universe, their promotion of the alleged “canonicity” of tie-ins as a crucial element of their appeal.

That helped infect genre fans with the twisted notion that whether a story “fits” is somehow more important than whether it’s good, as if all this were study material for a final exam, and you had to make sure you got the right answers. I think genre fandom as a whole would be much better off if those two influences hadn’t promoted a disproportionate fixation on “canon” and “continuity.”

Victor Gijsbers

February 15, 2016 at 10:22 am

“Mixing regents for spells is still incredibly tedious”. I’m also sure they would object to the process. :-) (I.e.: regents -> reagents.)

Jimmy Maher

February 15, 2016 at 10:32 am

:) Just realized I used both homonyms in the same article. Must be some sort of record. Anyway, thanks!

Ice Cream Jonsey

February 16, 2016 at 8:31 pm

Is anyone else playing this game using WHDLoad and an Amiga? I tried to do so last night and every sprite in the game seems to be corrupted. I haven’t found Amiga enthusiasts talking about this, so I’m curious if this is a system configuration thing or what. (This seems like the go-to place to talk about Ultima 5 at the moment as well.)

Jimmy Maher

February 17, 2016 at 6:52 am

I don’t have any personal experience with Ultima V on the Amiga, but your description sounds very much like a chip/fast RAM issue. I’d try setting the Amiga to just 1 MB of chip RAM and no fast RAM in the emulator, or run nofastmem on an already booted system before starting the game. If that doesn’t work, try 512 K of chip RAM and no fast RAM (although it’s hard to believe that a game released this late wouldn’t support Fatter Agnus, stranger things have happened).

If that doesn’t work, you might try the English Amiga Board: http://eab.abime.net/. Lots of techie types there who are usually very helpful…

Ice Cream Jonsey

February 18, 2016 at 7:30 pm

Thanks! You are the man. Some info I found before coming back to the comments on this article just now, and they agreed with what you thought. (One other comment indicated that there was a file in the zip of the WHDLOAD “version” of Ultima 5 that needs to be extracted on an Amiga and not a PC.) So between those two things I’ve got a plan. :)

Zark

February 17, 2016 at 10:53 pm

The thing that blew my mind after playing Ultima V was learning later that the virtue system really didn’t keep tabs on what the player did like in Ultima IV, but many players still behaved as if it was. I know I did.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2016 at 6:24 am

I think that can be read as one more commentary on the silliness of an absolutely rigid system of ethics. In a situation where you’re forced to become an outlaw, a sort of Robin Hood as Garriott always liked to described it, maybe it’s justifiable to steal a little bit from the treasury? But of course “the end justifies the means” is a slippery slope in itself… one more example of how ethics aren’t always so straightforward.

Koks

June 17, 2019 at 11:55 am

–> Zark

That’s not entirely the case. The 8 virtue system was replace by only one “secret” attribute called Karma (shortcut ctrl-k). Most of virtues doesn’t affect it (e.g. you can run from combat or kill fleeing enemies) but when you steal it will drop. And since you are very poor at the beginning of the game it is quite tempting to take food or torches and I’m quite sure that having low karma will affect prices in shops.

Tim Kaiser

March 1, 2016 at 3:11 pm

This is a great game. My first Ultima was U6 and I played that and U7 and a whole bunch of RPGs as a teenager. Later on, I played U5 and had that same feeling of adventure, discovery and exploration that I felt while playing U6 and 7. It’s amazing how Richard Garriott kept what I feel are the real tenants of Ultima: exploration, discovery and adventure consistent throughout the series (until it declined with U8).

I also remember that the game does get tedious by the end. I lost interest after exploring every town and castle and reasonably leveling up my guys and all I had to do to beat the game was get my avatar to level 8 and explore the GIGANTIC underworld. Combat was never a strong suit of the Ultima games.

Olivoist

March 13, 2016 at 11:30 pm

Very interesting and in-depth article, thank you.

What do you think about the free remake Ultima V Lazarus ?

I only played and finished this one and not the original game since its dialogues/characters are supposedly more fleshed out and well improved…

I really enjoyed this game a lot and definitely recommend it. Great world, great story, great role-play.

You’ll need Dungeon Siege and Windows XP ; or find a way to make this mod work with the Steam version of Dungeon Siege).

Ultima V Lazarus : http://www.u5lazarus.com/

Jimmy Maher

March 14, 2016 at 6:18 am

I’ve heard very good things about it, but never played it I’m afraid.

Peter Piers

March 14, 2016 at 8:38 pm

I’m still waiting for the Ultima game that I’m more likely to enjoy. I desperatly want to play the series, and I usually play every games. But… Ultimas 1, 2 and 3 disinterested me very early on, for all the reasons you already mentioned. Ultima 4 is not nearly playable enough for me to spend time on it – I wouldn’t trust it. Ultima 5 seemed to approach it, but apparently it’s still no it.

Maybe Ultima 6 will be the charm. You’ll let me know, I’m sure. :) I hate starting a series that late, but hey, between what I’ve played and what you wrote about, maybe I know all I need to know about U1-5!

Olivoist

March 15, 2016 at 1:07 am

Hi Peter, I suggest you try Ultima V Lazarus mentioned in my previous comment it’s apparently a really good “remastered version” of the original.

You’ll need Dungeon Siege and Windows XP ; or find a way to make this mod work with the Steam version of Dungeon Siege.

Get Ultima V Lazarus for free here with manual and all : http://www.u5lazarus.com/

Peter Piers

March 15, 2016 at 7:27 pm

But isn’t the essential game the same? The same string-of-pearls thread to follow? The same design? The old graphics really don’t bother me…

Olivoist

March 15, 2016 at 9:56 pm

The dev team and reviewers say that Ultima V Lazarus has improved dialogues/writing compared to the original.

http://www.rpgwatch.com/show/article?articleid=7&ref=0&id=37

Tass Cjelli

May 8, 2016 at 2:50 pm

U5 was *to me* when the Ultima series lost its magic.

James Andrews

July 14, 2016 at 3:51 am

I’m a little late to the conversation, but have to say Ultima V was my definitive Ultima.

I finished it (without cheating) 10 years after I first started it – from when I got it on my C64 as a kid, and then emulating it on the PC as a young adult.

( I think the C64 version was actually superior to the native PC version, as when you ran into monsters on the map they were more varied, mages with skeletons, ettins with headlesses ).

I think the game’s ambition is what kept me coming back.

Jared Roberts

April 12, 2017 at 5:26 pm

Your runic example is funny, and a good instance of where a small amount of book research might’ve helped quite a bit. The sign in your screenshot reads “ᚥᛖ᛫ᚱᚩᚥᚨᛚ᛫ᛕᚱᛁᛋᚩᚾ”, which is “Ye Royal Prison”. Of course, to sound vaguely old-timey “Ye” is used rather than “The”. But why do we have that odd construction in the first place? Old English actually borrowed the runic “ᚦ” to supplement the Latin alphabet for its “th” sound. Over time “ᚦ” ended up looking more like “ƿ” and then more like “y”. As printing grew, type imported from elsewhere in Europe often didn’t have English’s weird, already largely-outdated extra letter, so English typesetters just replaced it with the closest match they had, which was “y”.

*But none of this makes any sense if you’re actually using a runic script!* Britannian runes *have* “ᚦ”! And it even means “TH”! If these letters were actually in active use or holdovers from a time when they were, you’d just use the letter you really wanted, ᚦ, instead of a transliteration-of-the-closest-latin-match-to-a-decayed-form of the letter you really wanted and still have access to. Sigh.

Wikipedia has [more detail](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thorn_(letter)#Middle_and_Early_Modern_English).

Daragh Wickham

July 21, 2024 at 6:14 pm

Dropping in from the future to let you know that I thoroughly enjoyed this history tidbit!

Greg Cox

August 29, 2017 at 4:20 pm

You wrote, “to the elaborate word-building” rather than “world-building.”

I’m kind of surprised you describe V as having more plot than IV. It certainly has more backstory, but the plot was get more powerful, then dungeon delve. The scripted events you mention weren’t plottish in the sense that they had to happen, and could only happen once. You could skip the Iolo bifurcation with preparation, or lose party members one after another.

Jimmy Maher

August 30, 2017 at 7:53 am

Thanks!

I’m not sure I’d describe the much more elaborate and much more specific scenario of Ultima V as merely backstory. You do after all come onto the scene in medias res, as it were, and play the starring role in bringing the story to its conclusion. And just because it’s possible to avoid some parts of the plot, I’m not sure that invalidates the fact that there is a lot more highly specific plot *content*, as opposed to the more abstracted exercise in personal improvement that was Ultima IV.

whomever

August 30, 2017 at 6:24 pm

I’m with Jimmy, I think Ultima V has a more complex story (and I have the probably unpopular view that I actually prefer V to IV).

Jason Kankiewicz

November 22, 2017 at 5:35 pm

“it’s enough make” -> “it’s enough to make”?

“always a terribly compelling to” -> “always a terribly compelling one to”?

“somewhere on Britannia” -> “somewhere in Britannia”?

Jimmy Maher

November 24, 2017 at 2:56 pm

Thanks!

DerKastellan

June 2, 2020 at 7:37 am

“Ultima V” never ceases to amaze me. Discovering it around age 10 or 11 I got it for C64, including cloth map and coin. Its world book still sits on one of my shelves. It’s pretty much the only survivor from that time.

I never finished “Ultima V” as a teen. It was so damn hard. Even with a page out of a magazine full of clues (basically giving away what you needed to do) there was so much to do to get from here to there in terms of the plot, especially when it came to freeing Britannia from the three Shadowlords.

The game was insidious in how it could trap you. I had parties die because they got poisoned when traversing swamps. And I starved so often. Given that the game challenges you also to acquire some serious money it sure knows how to drain your coffers in terms of spell components and rations. The three monasteries of virtue could become death traps as they would lock their gates at night, and you had no wait out (overlooking possibly a well-placed secret door), each move bringing you closer to using a ration. In these locations you could consume many rations to pass the night as you couldn’t camp or sleep – all beds taken by residents who kick you out. Not finding a way out you could either starve by pressing the space bar over and over, murder somebody in their sleep and take their bed, or… actually, that’s it. “Empath Abbey” was a death trap in this sense – no innkeeper, no empty beds.

I roamed the countryside between Britannia and Yew to fight headless and orcs if I could, trying to avoid overpowered encounters while always hoping for good gear or gold. There was a grind involved and the game didn’t spare you. There was always elation at finding an ettin encounter (good loot) only to run from it seeing that the game generated too many. I remember a sense of threat and desperation. “Ultima V” was a hostile game.

And yet you could go practically anywhere, something unheard of. Some corners were harders than others, definitely the Underworld with its few defined exits, but if you kept your karma up you could actually hope to be resurrected in Lord British’s castle. I didn’t understand the consequences of this well, and the game doesn’t explain it much either, but it became part of gameplay to me.

Given how much of a walk in the park “Ultima VI” was, including the fact combat encounters, especially random ones, were hard to find in the overworld, “Ultima V” will always be defined to me by its relentlessness. If you manage to climb to level 5 out of 8, got some of the major magic items (like the crown and the flying carpet), you have a sense of control. Before that, the random cruelty of Britannia is in charge. You can’t even go to some places without poisoning yourself.

And yet – it had an open feel. The moon gates made for interesting travel options. Even islands were open to you. You could bridge distances that would otherwise be perilous hikes or ocean journeys. (This is of course got ridiculously easy in “Ultima VI” with being able to dial the moongates with the “Orb of the Moons”.) I don’t recall any other game feeling so free, open, and interesting as Ultima V and VI, with such great ability to actually travel in it. Some locations required special abilities to get to them, but most were readily available to the seeker. And the delight of walking near an open moongate and see it rise from the ground!

“Ultima V” was an exploration game rewarding those who would venture to every nook and cranny because it was there. It still does many exploration-based games one better and even though merely turn-based, is hard on its own merits without ultimately being unfair. Its overland mode was better than Ultima VI’s, as was its combat. While I can laud Ultima VI’s attempts to unify interface, frequently things happened off-screen, attacks coming from there, too, and allies ran off. “Ultima V” has quaint-looking modes, but each of them works just fine. Computers weren’t ready to handle a world at the resolution level of “Ultima VI” (or VII for that matter), but “Ultima V” hits a sweet spot.

And I fell in love with its clockwork world. Seldom has a world felt that alive and consistent. Quite a feat given how limited dialogue options are – you couldn’t change anybody’s mind, barely change anything about the people who were there. But boy, did they roam around, have their own little cycles, eat in the tavern. Compare a modern game trying the same – in “Witcher 3” people run around in small circles, and are absent at other times. But you don’t get a feeling they are living involved little lives, you feel like they create a visual semblance of having one. Being able to watch somebody get up, go about their activities, and understand what they were about was a joy in itself.

They sure don’t make games like that anymore. Graphical assets are expensive to create. They might let you light a torch but not take it, for example. In spite of the fact that there are engines handling the details of lighting if you let them. And so I remember, and occasionally play, “Ultima V” and “Ultima VI” still fondly.

DerKastellan

June 2, 2020 at 7:44 am

Regarding less monsters on the map… This was justified in-game. IIRC, the guide book stated that closing the major dungeons reduced the number of roaming monsters. Basically Britannia prospered since the time of the Avatar, expanding in populace, too, as for example the Britannies represent. Also, IIRC, the number of monsters in the countryside may have gotten worse with Lord British’s absence, largely owed to the influence of the new corruption in the land.

From a practical point of view this was probably done so you could actually explore Britannia in the first place. After all, why make such a wondrous creation and then discourage traveling in it?

Jerri Kohl

January 5, 2022 at 9:07 pm

Am I the only one who has noticed parallels between Ultima V and what’s going on right now in the world, or is this all just unspoken?

King Tut

January 29, 2023 at 11:43 pm

You are spot on. Ironic how Jimmy framed this in the article about the religious right trying to control things in the mid 80s and now how it’s the left who has been trying to control speech and actions in modern times.

David Ross

March 3, 2025 at 4:58 am

I was in college when I first encountered Galadriel wielding the One Ring.

Although Garriott and our host are men of the Left (or “creatures” of the Left in my less-charitable moments), this game’s morality is timeless. By accident, but by happy accident.

Matt

October 31, 2022 at 11:24 am

I first played this on an Atari ST. To this day I think the music was awesome. What I really loved most about Ultima V and Ultima IV was the opening music. Ultima IV was serene as if this was the state of reaching Avatarhood, while Ultima V was ominous and dark.

AS

March 6, 2023 at 6:29 am

Thanks for writing this history! Gradually working through the whole thing.

Wondering if footnote here is as intended. It is almost a direct copy of the main text.

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2023 at 6:42 am

Ouch. I changed footnote plugins at some point, and the new one behaves differently in some circumstances. Thanks!

Ben

May 23, 2023 at 10:38 pm

now matter how -> no matter how

an an uncanny -> an uncanny

Jimmy Maher

May 25, 2023 at 3:57 pm

Thanks!

Stash of Code

August 12, 2023 at 8:53 pm

Very interesting article. This great game has to be remembered. It’s my favorite.

Some years ago, I created a little trainer menu for old school games on the Amiga, and I decided to make it as an Ultima 5 tribute :

https://www.stashofcode.fr/scoopex-three-coding-of-menu-trainer-sur-amiga/

Vince

September 12, 2023 at 8:47 am

“then unleashed the three Shadowlords upon Britannia: personifications of the anti-Virtues of Falsehood, Hatred, and Cowardice.”

I feel very nerdy while nitpicking this, but each of the Shadowlords is the antithesis of one of the core “Principles” of the Ultima IV philosophy, respectively Truth, Love and Courage, rather than the eight “Virtues” derived from them.

Also, as far as I remember, Blackthorn will capture someone of your current party (not sure if it’s random of by party order), not necessarily Iolo.

Jimmy Maher

September 13, 2023 at 6:38 pm

Thanks!

Mark Norton

October 25, 2023 at 3:30 pm

Ultima V was “my” Ultima. I had U3, but never finished it until MUCH later. U5 I solved (and I still have the box, the feelies, and the certificate of completion because when it said you should write to Lord British and inform him of your accomplishment, I absolutely did.

While I tinkered with Ultima VI and was so frustrated that my machine wasn’t “good enough” for the Voodoo RAM system that was mandatory for U7, I never got into another one to the same degree. Ultima V hit a sweet spot of teenage time availability and doggedness to solve it.

The poster above mentioning the game draining money out is absolutely right. I distinctly remember having a notebook detailing which towns had the cheapest prices for various reagents and stocking up for a dungeon run mandated visiting each (I think Cove was REALLY cheap on some rare things if I remember right, Skara Brae another).

I’ll have to dig out the box. I know I still have that (along with Wizardry, Ultima 3, and Sorcerer) someplace. Never could talk myself into getting rid of them.)