I thought we’d take a trip together into Ultima II today. I’m not going to overdo the exercise, as that wouldn’t be much fun for you or me; there’s a lot of sameness and even a fair amount of outright tedium involved in winning the game. I will, however, try to hit most of the highlights and give you a fair picture of what sort of experience the game has on offer. As always, feel free to jump in and play for yourself if you like. Ultima II is available for sale at Good Old Games in combination with Ultima I and III. As we’ll see, it has plenty of issues, but there are certainly worse ways to spend six bucks.

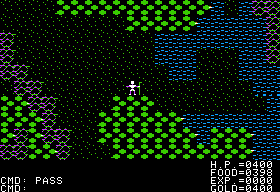

When we first create our character and start Ultima II proper, we might wonder just what Richard Garriott spent eighteen months working on. Aside from some animation that has been added to the water, everything looks just as it did in the last game. All of the graphics tiles appear to be exactly the same as those used last time around. As soon as we start to interact with the game, however, we have reason to bless Garriott’s move to assembly-language programming; everything is much, much snappier.

The map over which we wander is also different: this time we’re adventuring on Earth rather than Garriott’s old Dungeons and Dragons world of Sosaria. Moving over such familiar continents brings out the really weird scaling of the Ultima maps in a way that the previous game never did. Here London is exactly nine steps away from the southern tip of Italy, Africa eighteen steps from north to south. Ultima I presumably represented similarly immense distances with each tile, but because it was a fantasy creation I never really thought about it that way. I suppose there’s nothing absolutely prohibiting each step of our journey over the world map from representing days of travel. Yet Ultima II just doesn’t feel like it’s playing out over such an immense time scale; if it is, then the process of winning the game must involve decades (or more) of game time. And even that doesn’t explain why it’s possible to construct a bridge between North America and Europe by lining up a handful of ships. It makes a constant reminder that this is a highly constructed, highly artificial computer landscape we’re wandering through. That’s fine, I suppose… weird at first, but fine.

Speaking of weird: Ultima II may just have the most nonsensical fictional context I’ve ever seen in a CRPG — and that, my friends, is really saying something. Let me do my best to explain it. The screenshot below shows us passing one of the “time doors” that blink in and out of existence at various places on the landscape; charting them is the whole point of the ornate cloth map that was such a priority for Garriott. Through them we can journey to primordial history, when the Earth still contained just the single über-continent Pangea; to “B.C.,” a time “just before the dawn of civilization as history records it” where we begin the game; to 1990; or to the “Aftermath” of 2111, when the Earth is a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It’s also possible to go to the “Time of Legends,” a “time before time, peopled by creatures of myth and lore.” Along with the time doors themselves, Legends is the most obvious direct lift from Time Bandits in the game. The same place existed with the same name in the movie, and, there as here, was the scene of the final showdown between good and evil.

It seems that after we defeated the evil Mondain to win Ultima I, his protege Minax, “enchantress of evil,” took up his cause, albeit using a subtler approach:

For Minax is not content to spread evil among the good, causing misery and pain. She prefers to sow seeds of evil in the good and thus set the good against the good, leaving no person untouched. Destruction abounds — and those horrors known only to the once good, guilt and horror and self-hatred, taint the Earth.

The climax was the holocaust of 2111, Minax’s greatest triumph to date, in which ancient civilizations born of love of beauty and wisdom and thought turned upon one another and, in their vicious anger and hate, destroyed almost all of the very Earth that had nurtured them.

What makes no sense about all this is that Ultima I, you’ll remember, took place on Sosaria. Now we’re suddenly fighting the legacy of Mondain on Earth for reasons that, despite furious retconing by fans in later years, go completely unexplained in the game itself. Garriott said later that he chose to set Ultima II on Earth because “time travel needs context.” In other words, we need a familiar historical frame of reference on which to hang everything to get the contrast between, say, prehistoric times and contemporary society. Hopscotching through the timeline of a fictional world whose history means nothing to us just isn’t all that interesting. All of that makes perfect sense — except that the version of history depicted in the game has little to do with our Earth’s. Why are orcs wandering about contemporary Earth attacking people? Assuming Garriott didn’t have big plans for world domination in his immediate future, why does Lord British apparently rule the world of 1990 from his castle? Why can we buy phasers and power armor from merchants in prehistoric times? It feels like two (or more) games that smashed together, with everything that made sense about either spinning off into oblivion. Put less charitably, it all just seems really, really dumb, especially considering that Garriott could have had his time doors without at least the most obvious of the anachronisms just by setting his game on Sosaria. Better yet, he could have just made his time doors the moon gates of later Ultimas; there is absolutely no concept here of actions in one time affecting the others. Garriott gains nothing from time travel but a sop to his Time Bandits fixation and a whole lot of stupid.

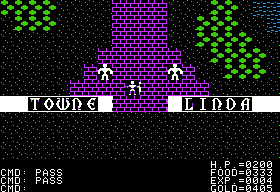

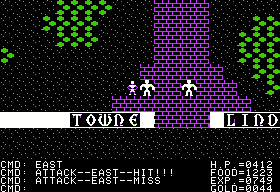

Anyway, we make our way to “Towne Linda,” located on the southern tip of Italy in B.C. When we enter we see one of the most obvious demonstrations of the work Garriott has been doing on his game engine since Ultima I: towns are now portrayed using the same tile graphics as the wilderness areas, filling many screens. Every city and village is now a unique creation, with its own geography and personality and its own selection of shops and services. There aren’t a lot of towns, just a few per time period (another thing that seems weird in the context of wandering a map of the Earth), but they do much to highlight the primacy of exploration over combat that has always made the Ultima experience unique. In the same spirit, it’s now possible to talk with anyone and everyone in the towns. In fact, it’s necessary to do so to pick up vital clues and information.

As Garriott has noted many times, walking around in the early Ultima can be a bit like wandering through the psyche of the young Richard, meeting the people, places, and interests that filled his time. Towne Linda, for instance, is named after his little sister, with whom he was very close. In a way this is kind of a fascinating concept — the videogame as intellectual landscape. As I’ve said before, one can picture an Annotated Ultima of a (fictional?) future where videogames are accepted as a form of literature. In it some hyper-dedicated scholar has laboriously run down all of the references and shout-outs in the same way that some have written books about Ulysses‘s allusions that are longer than Ulysses. And anyway, who can fault a guy for adoring his little sister? The problem comes when Garriott decides to get witty on us.

Now, Garriott is many things, with adjectival superlatives like “brilliant” very possibly among them. However, he’s not really a funny guy, and when he tries to be one here the results can be painful. Perhaps most grating, just because we have to see them over and over, are the generic phrases spouted by those for whom Garriott hasn’t written anything specific to say: like the guards who say, “Pay your taxes!” (why would a guard say that?), or the wizards with their immortal “Hex-E-Poo-Hex-On-You!” But even those with something unique to say are equally tedious, a jumble of obvious pop-culture references that isn’t exactly Gilmore Girls in its sophistication along with plenty of pointless non sequiturs. It feels like a teenage boy trying to ape Monty Python, which is just about the surest route to the profoundly unfunny I know of. Pity poor Richard; most of us left the humor of our teenage years in the past, but Garriott made the mistake of gifting his to the world. Reading some of the worst of this stuff brings on a sort of contact embarrassment for the guy.

Time Bandits: you have a lot to answer for. I’m sure Garriott imagined Ultima II as a manic, eccentric thrill ride like the movie, but, as he definitively demonstrates here, that tone is harder than it looks to pull off. At worst, it comes off like one of those amateur IF Competition entries in which the (usually young) author, realizing he’s written a game that makes no sense, tries to compensate by making it into an extended meta-comedy about the absurdities of text adventures — an exercise that fools exactly no one.

Like in Ultima I, saving the world from the forces of Evil in Ultima II requires that we not get too hung up on being Good. If we try to buy all of our equipment, food, and hit points (Ultima II persists with the bizarre mechanic of its two predecessors of making hit points a purchasable commodity), we find ourselves in a Sisyphus-like cycle of being able to earn just enough from killing monsters to keep ourselves in food and hit points, but not enough to buy better equipment or for doing any of a number of necessary things, like giving bribes to certain townspeople. To get ahead we need to, at a minimum, steal our food. Further, getting into a number of special areas requires keys that we can acquire only by attacking and killing town guards in cold blood.

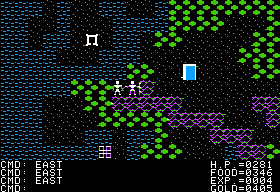

Getting from continent to continent requires a ship. In the screenshot at above right we’ve used some of our ill-gotten keys to steal one from the village of Port Boniface. Once we deal with this sea monster that apparently lives in the harbor, we’ll be home free. Since towns reset themselves every time you leave and bloody murder has no other consequences, you eventually start feeling sort of like the CRPG Addict did when he played:

As far as I can tell (and I admit I didn’t keep a careful log), the only recurring characters are Lord British, Iolo, and Gwenno. The latter two are encased in a grassy area in…I don’t know. One of the towns. Remembering how I killed Gwenno for her key in Ultima I and having by now fully internalized my role as a serial killer, I landed a bi-plane in the grassy area and hacked them both to death.

For my part, I found that — gameplay tip here! — I could earn gold fastest by attacking this one townsperson who is always right at the entrance of the town of Le Jester in prehistoric Africa. I must have killed him and run out of town before the guards could get to me 500 times. Yes, Ultima II makes serial killers of us all.

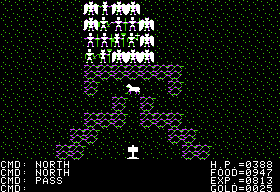

Next time we’ll penetrate all the way into Minax’s lair in the Time of Legends. The assortment of monsters that greet us when we step through a time door to go there is a pretty good sign that we’re in the right place…

Nathan

October 15, 2012 at 7:18 pm

Minax != Minix.

Jimmy Maher

October 16, 2012 at 7:12 am

Unlike Windows, Minix is not content to spread evil among the good, causing misery and pain. She prefers to sow seeds of evil in the good through her microkernel architecture. Only you, Linus Torvalds, can vanquish her and make the world safe for open source.

:) Thanks for the correction!

Andrew Plotkin

October 15, 2012 at 8:52 pm

Oh, that’s not fair. The time-gates give you the experience of walking through a world in different stages of history, and seeing the geography shift from time period to time period. That’s one of the basic forms of environmental storytelling. You don’t have to be *told* that the post-apocalyptic world is post-apocalyptic; you can see it in the eroded coastlines and missing cities.

Zork 3 did some of this, but U2 was the first game to present it in large scale. (That I’m aware of.)

I’m not saying it did a great job with the idea, but again, it was awfully cool to me as a twelve-year-old.

(I think I did my gold-farming by cruising around the world in a ship for hours, and then slaughtering the accumulated monsters with a cannon. I definitely recall reading a book while holding down the “east” arrow key.)

Jimmy Maher

October 16, 2012 at 7:27 am

I just can’t quite make that stretch, which I’m happy to accept may very possibly be because I’m no longer twelve. The continents of 2111 are not so much “eroded” as completely reshaped and rearranged. The number of settlements are reduced from three in 1990 to the one in 2111, not a hugely dramatic drop. Yes, orcs and other monsters wander the landscape of 2111, but they also (inexplicably) do so in 1990. I think you’d have a very hard time realizing that these worlds were actually the same world at different points of time if the manual didn’t tell you they were.

Captain Rufus

October 16, 2012 at 12:55 am

Everyone playing the game in the modern era does that. Most early RPGs were 1-2 hours of exploring and plot solving and 38 odd hours of killing and grinding. Its just you would be exploring and figuring most of it out on your own as opposed to shortcutting it as we do now which turns these games into the combat heavy exercises in boredom they seem. We weren’t supposed to know how LITTLE you really needed to do to win these things thus we would get the XP and items we needed more naturally. (I am playing Bard’s Tale on the Kindle Fire sort of like that. Trying to properly self map and not assume I know mostly what to do via Quest for Clues. So I don’t just spend 10 hours killing nearly 400 Berserkers over and over again and play it “properly”.)

But I was running an RPG campaign that mixed Ultima and Bard’s Tale. I used the various Ultima maps as the points in time. Pagan was the Pangea era. U1 the Age of Mondain. U4-5 the default time. U9 the Age of Ruins. Course unlike Garriott I had these maps and could take advantage of them.. But.. it could have been doable on early 16 bit systems. Early age could have had dinosaurs and more primitive weapons, mid age could be the U1 maps recycled, modern age could have been another map set with modern equipment, and future/apocalypse age could be different still with guns and space alien monsters.

Yet given that U2 was 82 and 48K of RAM was HUGE back then.. If it had been made in 86-87 with 128K of RAM and multiple floppies (and the 8 bit computing market actually accepted 128k systems as default instead of largely stopping at 48 or 64 depending on machine…) it would have been far more feasible.

But considering what they pulled off on C64s in 90-91 it WAS possible even with that machine’s specs…

Jimmy Maher

October 16, 2012 at 7:34 am

Yet the killing and grinding in Ultima II is unusually tedious. Garriott normally did a very good job of giving the player goals to pursue, so that the grinding came more organically as part of the process of discovery and exploration: i.e., defeating the Big Foozle requires this thingamabob which rests on the bottom level of this dungeon. In the process of penetrating the dungeon, the grinding came naturally.

In Ultima II, however, his design sensibility deserts him entirely. Suddenly we’re left with holding down the arrow key while reading a book, which is No Fun even for most twelve-year-olds. The design is just fundamentally broken.

Lex Spoon

October 16, 2012 at 12:34 pm

I found the early Ultima series to elicit the wonder of exploration as well as the best computer games out there. The closest comparable game I can think of is Starflight, which cane years later and had a massively larger amount of in-game text.

The Ultima II timegates I found to be particularly compelling. Seeing the world change in different epochs worked for me. Also, there’s something really cool about seeing a portal to another location rise out of the ground in the middle of the night. It’s a staple of fantasy stories, and it’s something Garriot is very good about tapping into.

I agree that the game has geographic scaling oddities, but I have never heard it called out as a design flaw. Lots of CRPGs do the same thing. By shrinking the distance between cities and geographic features, they allow you to interactively move your character around the overworld and still experience something interesting every few minutes.

One thing I will grant you is that I found Ultima 1-3 completely unwinnable without going to an external source, which at the time I didn’t have available. Food runs out way too quickly. Also, the 5-word sentences are way too cryptic for me, especially given the noise of things like hex-e-poo. As such, I spent all my time in these early Ultimas just wandering around and fighting baddies. I didn’t even go into the dungeons very much; they weren’t as fun and I didn’t see what the point was.

David Chou

February 1, 2019 at 6:08 am

Any idea why the original C-64 version by Sierra On-Line had “daytime” graphics — and why all the Ultimas had everything looking like night?? I’ve never seen this addressed before (not that I’m a scholar of such matters [but it’s almost certainly nothing to do with “memory,” as Ultima II demonstrates]).

Also, did the first Ultima also have those “daytime” graphics, on any platform?

Just curious. Nice site!

stepped pyramids

May 15, 2019 at 11:50 pm

The original was on Apple II, and the C64 version was a port (not by Richard Garriott). The Apple II hi-res mode has a very limited color selection — black, white, purple, green, blue, and orange. All of the colors are very bright/saturated. Also, for technical reasons not really worth getting into here (see link below), there were limitations on drawing different colors adjacent to each other if one of those colors was not white or black. As a result, you’ll see a lot of Apple II hi-res games (with the characteristic text lines at the bottom) with a predominantly black screen with white and colored line art. Players at the time wouldn’t have interpreted this as indicating “night”.

The Commodore 64, on the other hand, has a larger (16 colors) and less saturated color palette. Black and white don’t have any special treatment in the palette, and the more muted colors pair together much better. So, to put a long story short, the reason the C64 has a more colorful “daytime” look is because the hardware supported it and the programmer thought it was a good idea.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_II_graphics#Color_on_the_Apple_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOS_Technology_VIC-II#Colors

Leo Velles

June 27, 2019 at 5:59 pm

Maybe a little typo here? (End of third paragraph):

“That fine, I suppose… weird at first, but fine”.

Shouldn’t be “That’s fine or that is fine”?

Not sure, english is not my first language

Jimmy Maher

July 5, 2019 at 7:11 am

Thanks!

Ben

August 9, 2020 at 7:11 pm

that, my friends is -> that, my friends, is

protege -> protégée

ret-coning -> retconning

Jimmy Maher

August 10, 2020 at 8:20 am

Thanks! (“Protege” is an acceptable Anglicized version of the French.)

madscijr

April 16, 2021 at 3:17 am

It’s been a while since I played Ultima 2, but I remember it being pretty fun.

My first taste of the series (and CRPGs in general) was with III on the C64 back in 1985, which blew me away. Immediately after completing it, I chose II as my next adventure, and despite the graphics being more threadbare (at least on the C64 version, published by Sierra Online if I recall and not Origin Systems), and the weird presence of futuristic weapons (where Ultima 3 had a more traditionally medieval D&D type mileau one would expect), I thought it was pretty fun and moved faster having only one player instead of a party of 4.

Yeah, Mr. Garriot was still finding his way with the first couple games, but cut him a break, he was all of what, 18 or 19 years old at the time? When I look back on my creations at that age, they are hardly even that developed or mature. The important thing is that he did manage to learn from his mistakes, and continued to make the games better.

I still think Ultima III was awesome, and IV and V were masterpieces. I solved IV, and made it pretty far into V but other interests took over (like making my own games and creative writing and guitar) so I never finished it. When VI came out I took a look and decided I hated the direction they went with the quasi-3Dish graphics. And as computers became more powerful, I think they only moved further away from the simple tile games which were barely a step beyond the graph paper of classic D&D. For me, the look & feel of Ultimas 3-5 was *perfect* – you could visualize more than with a text adventure, like graph paper come to life, but still leaving enough to your imagination.

Ultima 2 hadn’t got that look & feel down yet, the world wasn’t yet as consistant, the lore as fully developed as it would be, but it took some major steps toward getting there and was fun to play. And it was also cool to go back and experience this earlier game and appreciate how it had evolved.

Adam Huemer

February 26, 2025 at 1:17 pm

This review shows that you are much more a fan of adventure games than of role playing games. ;)

However, like mentioned before, it’s great to read all the articles you did.