In 1989, Trip Hawkins reluctantly decided to shift Electronic Arts’s strategic focus from home computers to videogame consoles, thereby to “reach millions of customers.” That decision was reaching fruition by 1992. For the first time that year, EA’s console games outsold those they published for personal computers. The whole image of the company was changing, leaving behind the last vestiges of the high-toned “software artists” era of old in favor of something less intellectual and more visceral — something aimed at the mass market rather than a quirky elite.

Still, corporate cultures don’t change overnight, and the EA of 1992 continued to release some computer games which were more in keeping with their image of the 1980s than that of this new decade. One of the most interesting and rewarding of these aberrations — call them the product of corporate inertia — was a game called The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes, whose origin story doesn’t exactly lead one to expect a work of brilliance but which is in fact one of the finest, most faithful interpretations of the legendary detective in the deerstalker cap ever to make its way onto a monitor screen.

The initial impetus for Lost Files was provided by an EA producer named Christopher Erhardt. After studying film and psychology at university, Erhardt joined the games industry in 1987, when he came to Infocom to become the in-house producer for their latter-day lineup of graphical games from outside developers, such as Quarterstaff, BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, and Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur. When Infocom was shuttered in 1989, he moved on to EA in the same role, helming a number of the early Sega Genesis games that did so much to establish the company’s new identity. His success on that front gave him a fair amount of pull, and so he pitched a pet idea of his: for a sort of computerized board game that would star Sherlock Holmes along with a rotating cast of suspects, crimes, and motives, similar to the old 221B Baker Street board game as well as a classic computer game from Accolade called Killed Until Dead. It turned out that EA’s management weren’t yet totally closed to the idea of computer games that were, as Erhardt would later put it, “unusual and not aimed at the mass market” — as long, that is, as they could be done fairly inexpensively.

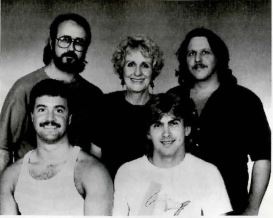

Mythos Software. On the top row are David Wood, Elinor Mavor, and Scott Mavor. On the bottom row are James Ferguson and John Dunn.

In order to meet the latter condition, Erhardt enlisted a tiny Tempe, Arizona, company known as Mythos Software — not to be confused with the contemporaneous British strategy-games developer Mythos Games. This Mythos was being run by one James Ferguson, its fresh-out-of-university founder, from the basement of his parents’ house. He was trying to break into the wider world of software development that lay outside the bounds of the strictly local contracts he had fulfilled so far; his inexperience and eagerness ensured that Mythos would work cheap. And in addition to cut-rate pricing, Ferguson had another secret weapon to deploy: an artist named Scott Mavor who had a very special way with pixel graphics, a technique that EA’s in-house employees would later come to refer to as “the Mavor glow.” The highly motivated Mythos, working to Erhardt’s specifications, created a demo in less than two weeks that was impressive enough to win the project a tentative green light.

Another EA employee, a technical writer named Eric Lindstrom, saw the demo and suggested turning what had been planned as a computerized board game into a more narratively ambitious point-and-click adventure game. When Erhardt proved receptive to the suggestion, Lindstrom put together the outline of a story, “The Mystery of the Serrated Scalpel.” He told Erhardt that he knew the perfect person to bring the story to life: one of his colleagues among EA’s manual writers, a passionate Sherlock Holmes aficionado — he claimed to have read Arthur Conan Doyle’s complete canon of Holmes stories “two or three times” — named R.J. Berg.

The project’s footing inside EA was constantly uncertain. Christopher Erhardt says he “felt like I was playing the Princess Bride, and the dread pirate Roberts was coming. It was always, ‘Yep – we may cancel it.'” But in the end the team was allowed to complete their point-and-click mystery, despite it being so utterly out of step with EA’s current strategic focus, and it was quietly released in the fall of 1992.

I find the critical dialog that followed, both in the immediate wake of Lost Files‘s release and many years later in Internet circles, to be unusually interesting. In particular, I’d like to quote at some length from Computer Gaming World‘s original review, which was written by Charles Ardai, one of the boldest and most thoughtful — and most entertaining — game reviewers of the time; this I say even as I find myself disagreeing with his conclusions far more often than not. His review opens thus:

If there is any character who has appeared in more computer games than Nintendo’s plump little goldmine, Mario, it has to be Sherlock Holmes. There have been almost a dozen Holmes-inspired games over the years, one of the best being Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, which is currently available in two different CD-ROM editions from ICOM. Other valiant attempts have included Imagic’s Sherlock Holmes in Another Bow, in which Holmes took a sea voyage with Gertrude Stein, Picasso, Thomas Edison, and Houdini, among others; and Infocom’s deadly serious Sherlock: Riddle of the Crown Jewels.

The difference between Holmes and Mario games, however, is that new Mario games are always coming out because the old ones sold like gangbusters, while new Sherlock Holmes games come out in spite of the fact that their predecessors sold like space heaters in the Sahara. It is noteworthy that, until ICOM, no company had ever released more than one Sherlock Holmes game, while all the Mario games come from the same source. It is also worth noting that the Holmes curse is not limited to games: the last few Holmes movies, such as Without a Clue and Young Sherlock Holmes, were not exactly box-office blockbusters.

The paradox of Sherlock Holmes can be stated so: while not that many people actually like the original Sherlock Holmes stories, everyone seems to think that everyone else adores them. Like Tarzan and Hawkeye, Holmes is a literary icon, universally known and much-beloved as a character in the abstract — not, however, as part of any single work. Finding someone who has actually read and enjoyed the writing of Edgar Rice Burroughs, James Fenimore Cooper, or Arthur Conan Doyle requires the patience of Diogenes. Most people know the character from television and the movies, at best; at worst, from reviews of television shows and movies they never bothered to see.

So, why do new Holmes adaptations surface with such regularity? Because the character is already famous and the material is in the public domain (thereby mitigating the requisite licensing fees associated with famous characters of more recent vintage. Batman or Indiana Jones, for instance.) Another answer is that Sherlock Holmes is seen as bridging the gap between entertainment and literature. Game companies presumably hope to cash in on the recognition factor and have some of the character’s ponderous respectability rub off on their product. They also figure that they can’t go wrong basing their games on a body of work that has endured for almost a century.

Unfortunately for them, they are wrong. There are only so many copies of a game that one can sell to members of the Baker Street Irregulars (the world’s largest and best-known Sherlock Holmes fan club), and a vogue for Victoriana has never really caught on among the rest of the game-buying population. The result is that, while Holmes games have been good, bad, and indifferent, their success has been uniformly mediocre.

This delightfully cynical opening gambit is so elegantly put together that one almost hesitates to puncture its cogency with facts. Sadly, though, puncture we must. While there were certainly Sherlock Holmes games released prior to Lost Files that flopped, there’s no evidence to suggest that this was the fault of the famous detective with his name on the box, and plenty of evidence to the contrary: that his name could, under the right circumstances, deliver at least a modest sales boost. In addition to the Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective CD-ROM productions, a counter-example to Ardai’s thesis that’s so huge even he has to acknowledge it — the first volume of that series sold over 1 million units — there’s also the Melbourne House text adventure Sherlock; that game, the hotly anticipated followup to the bestselling-text-adventure-of-all-time The Hobbit, likely sold well over 100,000 units in its own right in the much smaller market of the Europe of 1984. Even Infocom’s Riddle of the Crown Jewels, while by no means a smash hit, sold significantly better than usual for an Infocom game in the sunset of the company’s text-only era. (Nor would I describe that game as “deadly serious” — I could go with “respectful” at most — but that’s perhaps picking nits.)

Still, setting aside those inconvenient details, it’s worth considering this broader question of just why there have been so many Sherlock Holmes games over the years. Certainly the character doesn’t have the same immediate appeal with the traditional gaming demographic as heavyweight properties like Star Wars and Star Trek, Frodo Baggins and Indiana Jones — or, for that matter, the born-in-a-videogame Super Mario. The reason for Sherlock’s ubiquity in the face of his more limited appeal is, of course, crystal clear, as Ardai recognizes: he’s in the public domain, meaning anyone who wishes to can make a Sherlock Holmes game at any time without paying anyone. [1]There have been occasional questions about the extent to which Sherlock Holmes and his supporting cast truly are outside all bounds of copyright, usually predicated on the fact that the final dozen stories were published in the 1920s, the beginning of the modern copyright era, and thus remain protected. R.J. Berg remembers giving “two copies of the game and a really trivial amount of money” to Arthur Conan Doyle’s aged granddaughter, just to head off any trouble on that front. When a sequel to Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes was published in 1996, no permission whatsoever was sought or demanded.

As such, Holmes occupies a nearly unique position in our culture. He’s one of the last great fictional icons, historically speaking, who’s so blessedly free of intellectual-property restrictions. Absolutely everyone, whether they’ve ever read a story or seen a film featuring him or not, knows him. The only characters with a remotely similar degree of recognizability who postdate him are Dracula, the Wizard of Oz, and Peter Pan — and neither of the latter two at least presents writers with quite the same temptation to tell new story after story after story.

As is noted in Lost Files‘s manual, Sherlock Holmes has become such an indelible part of our cultural memory that when we see him we experience a sort of vicarious nostalgia for a London none of us ever knew: “Gas lamps, the sound of horses’ hooves, steam locomotives, and romantic street cries. And then there is the atmosphere of that cozy room in Baker Street: Holmes in his armchair before a roaring coal fire, legs stretched out before him, listening with Dr. Watson to yet another bizarre story.” One might say that Sherlock Holmes gets the chronological balance just right, managing to feel both comfortably, nostalgically traditional and yet also relevant and relatable. In contrast to the Victorian scenery around him, his point of view as a character feels essentially modern, applicable to modern modes of storytelling. I’m not sure that any other fictional character combines this quality to quite the same extent with a freedom from copyright lawyers. These factors have fostered an entire creative subculture of Sherlockia which spans the landscape of modern media, dwarfing Arthur Conan Doyle’s canonical four novels and 56 short stories by multiple orders of magnitude.

The relative modernity of Sherlock Holmes is especially important in the context of interactive adaptations. The player of any narrative-driven game needs a frame of reference — needs to understand what’s expected of her in the role she’s expected to play. Thankfully, the divide between Sherlock Holmes and the likes of C.S.I. is a matter of technology rather than philosophy; Sherlock too solves crimes through rationality, combining physical evidence, eyewitness and suspect interviews, and logical deduction to reach a conclusion. Other legendary characters don’t share our modern mindset; it’s much more difficult for the player to step into the role of an ancient Greek hero who solves problems by sacrificing to the gods or an Arthurian knight who views every event as a crucible of personal honor. (Anyone doubtful of Sherlock Holmes’s efficacy in commercial computer games should have a look at the dire commercial history of Arthurian games.)

With so much material to make sense of, post-Doyle adventures of Sherlock Holmes get sorted on the basis of various criteria. One of these is revisionism versus faithfulness. While some adaptations go so far as to transport Sherlock and his cronies hook, line, and sinker into our own times, others make a virtue out of hewing steadfastly to the character and setting described by Arthur Conan Doyle. This spirit of Sherlockian fundamentalism, if you will, is just one more facet of our long cultural dialog around the detective, usually manifesting as a reactionary return to the roots when other recent interpretations are judged to have wandered too far afield.

No matter how much the Sherlockian fundamentalists kick and scream, however, the fact remains that the Sherlock Holmes of the popular imagination has long since become a pastiche of interpretations reflecting changing social mores and cultural priorities. That’s fair enough in itself — it’s much of the reason why Doyle’s timeless sleuth remains so timeless — but it does make it all too easy to lose sight of Holmes and Watson as originally conceived in the stories. Just to cite the most obvious example: Holmes’s famous deerstalker cap is never mentioned in the text of the tales, and only appeared on a few occasions in the illustrations that originally accompanied them. The deerstalker became such an iconic part of the character only after it was sported by the actor Basil Rathbone as an item of daily wear — an odd choice for the urban Holmes, given that it was, as the name would imply, a piece of hunting apparel normally worn by sporting gentlemen in the countryside — in a long series of films, beginning with The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1939.

Although Lost Files doesn’t go so far as to forgo the deerstalker — there are, after all, limits to these things — it does generally try to take its cue from the original stories rather than the patchwork of interpretations that followed them. Berg:

I definitely aimed for Holmesian authenticity. I’d like to think that, if he were alive, Doyle would like the game. After all, the characters of Holmes and Watson have been manipulated quite a bit by the various media they’ve appeared in, especially the films. For example, the Watson of Lost Files is definitely Doyle’s Watson, competent and intelligent, rather than the bumbling character portrayed in many of the movies. I also wanted to retain Holmes’s peculiar personality. He’s really not that likable a character; he’s arrogant, a misogynist, and extremely smug.

This spirit of authenticity extends to the game’s portrayal of Victorian London. There are, I’ve always thought, two tiers when it comes to realistic portrayals of real places in fiction. Authors on the second tier have done a whole lot of earnest research into their subject, and they’re very eager to show it all to you, filling your head with explicit descriptions of things which a person who actually lived in that setting would never think twice about, so ingrained are they in daily existence. Authors on the top tier, by contrast, have seemingly absorbed the setting through their pores, and write stories that effortlessly evoke it without beating you over the head with all the book research they did to reach this point of imaginative mastery.

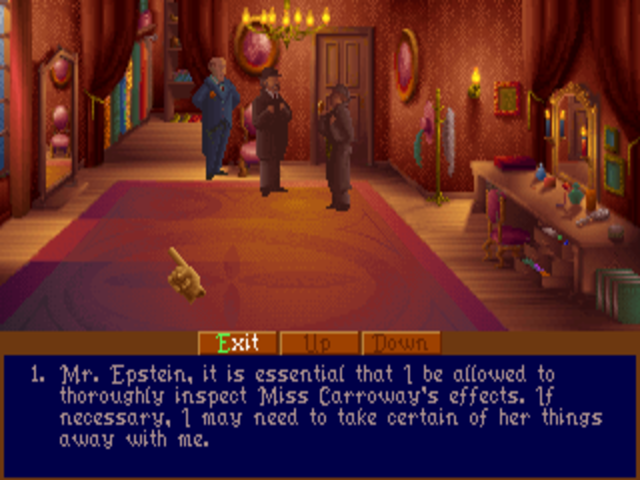

Lost Files largely meets the latter bar as it sends you around to the jewelers and tobacconists, theaters and pubs, opulent mansions and squalid tenements of fin-de-siècle London. The details are there for when you need them or decide to go looking for them; just try mousing around the interior of 221B Baker Street. (“A typical sitting-room chair. The sheen of its wine-red velveteen covering shows that it is well-used. A dark purple silk dressing gown with a rolled collar is carelessly crumpled on the seat and the antimacassar requires changing.”) More impressive, though, is the way that the game just breathes its setting in that subtle way that can only be achieved by a writer with both a lighter touch and countless hours of immersion in the period at his command. For example Berg spent time reading Charles Dickens as well as Arthur Conan Doyle in order to capture the subtle rhythms of Victorian English in his conversations. This version of Holmes’s London isn’t the frozen-in-amber museum exhibit it sometimes comes off as in other works of Sherlockia. “We wanted a dirty game,” says Eric Lindstrom. “We wanted people to feel that people were burning coal, that they could see who was walking in the streets. Just as it was in London at the time.”

There is, however, one important exception to the game’s rule of faithfulness to the original stories: Lost Files presents a mystery that the reader can actually solve. In light of the place Holmes holds in our cultural memory as the ultimate detective, one of the great ironies of Doyle’s stories is that they really aren’t very good mysteries at all by the standard of later mystery fiction — a standard which holds a good mystery to be an implicit contest between writer and reader, in which the reader is presented with all the clues and challenged to solve the case before the writer’s detective does so. Doyle’s stories cheat egregiously by this standard, hiding vital evidence from the reader, and often positing a case’s solution on a chain of conjecture that’s nowhere near as ironclad as the great detective presents it to be. Eric Lindstrom:

The [original] stories do not work the way we are used to today. They are not whodunnits; whodunnits only became popular later. Readers have virtually no way of finding out who the culprit is. Sometimes the offender does not even appear in the plot. These are adventure stories narrated from the perspective of Dr. Watson.

For obvious reasons, Lost Files can’t get away with being faithful to this aspect of the Sherlock Holmes tradition. And so the mystery it presents is straight out of Arthur Conan Doyle — except that it plays fair. Notably, you play as Holmes himself, not, as in the original stories, as Watson. Thus you know what Holmes knows, and the game can’t pull the dirty trick on you, even if it wanted to, of hiding information until the big reveal at the end. Many other works of Sherlockia — even the otherwise traditionalist ones — adapt the same approach, responding to our post-nineteenth-century perception of what a good mystery story should be.

And make no mistake: “The Case of the Serrated Scalpel” is a very good mystery indeed. I hesitate to spoil your pleasure in it by saying too much, and so will only state that what begins as the apparently random murder of an actress in an alley behind the Regency Theatre — perhaps by Jack the Ripper, leaving Whitechapel and trying his hand in the posher environs of Mayfair? — keeps expanding in scope, encompassing more deaths and more and more Powerful People with Secrets to Keep. As I played, I was excited every time I made a breakthrough. Even better, I felt like a detective, to perhaps a greater extent than in any computer game I’ve ever played. Among games in general, I can only compare the feeling of solving this mystery to that of tackling some of the more satisfying cases in the Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective tabletop game.

Part of the reason the mystery comes together so well is just down to good adventure-game design principles, of the sort which eluded so many other contemporary practitioners of the genre. Berg:

The idea was to produce a game that was different from existing adventures, which I frankly felt were often tedious. We wanted to eliminate the elements that tend to detract from the reality of the experience — things like having to die in order to learn some crucial information, constantly having to re-cover the same territory, and the tendency to simply pick up and use every object you encounter. We wanted to give players a deeper experience.

So, there are none of the dreaded adventure-game dead ends in Lost Files. More interestingly, the design does, as Berg alludes above, mostly eschew the typical use-unlikely-object-in-unlikely-place model of gameplay. Tellingly, the few places where it fails to do so are the weakest parts of the game.

As I’ve noted before, the classic approach to the adventure game, as a series of physical puzzles to solve, can be hugely entertaining, but it almost inevitably pushes a game toward comedy, often in spite of its designers’ best intentions. Most of us have played alleged interactive mysteries that leave you forever messing about with slider puzzles and trivial practical problems of the sort that any real detective would solve in five minutes, just by calling for backup. In Infocom’s Sherlock: Riddle of the Crown Jewels, for example, you learn that a stolen ruby is hidden in the eye of the statue of Lord Nelson on top of Nelson’s Column, and then get to spend the next little while trying to get a pigeon to fetch it for you instead of, you know, just telling Inspector Lestrade to send out a work crew. Lost Files does its level best to resist the siren call of the trivial puzzle, and, with only occasional exceptions, it succeeds. Thereby is the game freed to become one of the best interactive invocations of a classic mystery story ever. You spend your time collecting and examining physical evidence, interviewing suspects, and piecing together the crime’s logic, not solving arbitrary road-block puzzles. Lost Files is one of the few ostensibly serious adventure games of its era which manages to maintain the appropriate gravitas throughout, without any jarring breaks in tone.

This isn’t to say that it’s po-faced or entirely without humorous notes; the writing is a consistent delight, filled with incisive descriptions and flashes of dry wit, subtle in all the ways most computer-game writing is not. Consider, for example, this description of a fussy jeweler: “The proprietor is a stern-looking woman, cordial more through effort than personality. She frequently stares at the cleaning girl who tidies the floor, to make sure she is still hard at work.” Yes, this character is a type more than a personality — but how deftly is that type conveyed! In two sentences, we come to know this woman. I’d go so far as to call R.J. Berg’s prose on the whole better than that of the rather stolid Arthur Conan Doyle, who tended to bloviate on a bit too much in that all too typical Victorian style.

The fine writing lends the game a rare quality that seems doubly incongruous when one considers the time in which it was created, when multimedia was all the rage and everyone was rushing to embrace voice acting and “interactive movies.” Ditto the company which published it, who were pushing aggressively toward the forefront of the new mass-media-oriented approach to games. In spite of all that, darned if Lost Files doesn’t feel downright literary — thoughtful, measured, intelligent, a game to take in slowly over a cup of tea. Further enhancing the effect is its most unique single technical feature: everything you do in the game is meticulously recorded in an in-game journal kept by the indefatigable Dr. Watson. The journal will run into the hundreds of onscreen “pages” by the time you’re all done. It reads surprisingly well too; it’s not inconceivable to imagine printing it out — the handy option to print it or save it to a file is provided — and giving it to someone else to read with pleasure. That’s a high standard indeed, one which vanishingly few games could meet. But I think that The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes just about manages it.

Having given so much praise to Lindstrom and Berg’s design and writing, I have to give due credit as well to Mythos Software’s efforts to bring it all to life. The interface of Lost Files is thoroughly refined and pleasant to work with, a remarkable achievement considering that this was the first point-and-click graphic adventure to be made by everyone involved. An optional but extremely handy hotspot finder minimizes the burden of pixel hunting, and the interface is full of other thoughtful touches, like a default action that is attached to each object; this saves you more often than not from having to make two clicks to carry out an action.

Finally, praise must be given to Scott Mavor’s “Mavor glow” graphics as well. To minimize the jagged edges typical of pictures drawn in the fairly low resolution of 256-color VGA graphics, Mavor avoided sharp shifts in color from pixel to pixel. Instead he blended his edges together gradually, creating a lovely, painterly effect that does indeed almost seem to glow. Scott’s mother Elinor Mavor, who worked with him to finish up the art in the latter stages of the project: [2]Scott Mavor died of cancer in 2008

Working with just 256 colors, Scott showed me how he created graduating palettes of each one, which allowed him to do what he called “getting rid of the dots” in each scene. To further mute the pixels, he kept the colors on the darker side, which also enhanced the Victorian mood.

Weaving the illusion of continuous-tone artwork with all those little “dots” made us buggy-eyed after a long day’s work. One night, I woke up, went into the bathroom, turned on the light, and the world just pixelated in front of me. Scary imprints on my retinas had followed me away from the computer monitor, rendering my vision as a pointillistic painting à la George Seurat.

While the graphics of its contemporaries pop out at you with bright, bold colors, the palette of Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes smacks more of the “brown sauce” of the old masters — murky, mysterious, not initially jaw-dropping but totally in keeping with the mood of the script. As you, playing the diligent detective, begin to scan them carefully, the pictures reveal more and more details of the sort that are all too easy to overlook at a quick glance. It makes for an unusually mature aesthetic statement, and a look that can be mistaken for that of no other game.

Given all its strengths, I find it surprising that Lost Files has gotten more than its share of critical flak over the years. I have a theory as to why that should be, but before I get to that I’ll let one of the naysayers share his point of view. Even after admitting that the story is “a ripping yarn,” the graphics atmospheric, the period details correct, and the writing very good, Charles Ardai concludes his review thusly:

Don’t get me wrong: the dialogue is well-written, the choices are entertaining, and in most cases the actions the game requires the player to perform are very interesting. The story is good and the game is a pleasure to watch. Yet, that is what one does — watch.

This game wants, more than anything in the world, to be a Sherlock Holmes movie. Though it would be a very good one if it were, it is not. Therefore, it is deeply and resoundingly unsatisfying. The plot unfolds quite well, with plenty of twists, but the player has no more control over it than he would if he were reading a novel. The player is, at best, like an actor in a play. Unfortunately, said actor has not been given a copy of the script. He has to hit his marks and say his lines by figuring out the cues given by the other characters and reading his lines off the computer equivalent of cue cards.

If this is what one wants — a fine Sherlock Holmes pastiche played out on the computer screen, with the player nominally putting the lead character through his paces — fine. “The Case of the Serrated Scalpel” delivers all that one could hope for in that vein. If one wants a game — an interactive experience in which one’s decisions have an effect on what happens — this piece of software is likely to disappoint.

The excellent German podcast Stay Forever criticized the game along similar — albeit milder — lines in 2012. And in his mostly glowing 2018 review of the game for The Adventure Gamer joint-blogging project, Joe Pranevich as well noted a certain distancing effect, which he said made him feel not so much like he was playing Sherlock Holmes and solving a mystery as watching Sherlock do the solving. The mystery, he further notes — correctly — can for the most part be solved by brute force by the patient but obtuse player, simply by picking every single conversation option when talking to every single character and showing each of them every single object you’ve collected.

At the extreme, criticisms like these would seem to encroach on the territory staked out by the noted adventure-game-hater Chris Crawford, who insists that the entire genre is a lie because it cannot offer the player the ability to do anything she wants whenever she wants. I generally find such complaints to be a colossal bore, premised on a misunderstanding of what people who enjoy adventure games find most enjoyable about them in the first place. But I do find it intriguing that these sorts of complaints keep turning up so often in the case of this specific game, and that they’re sometimes voiced even by critics generally friendly to the genre. My theory is that the mystery of Lost Files may be just a little bit too good: it’s just enticing enough, and just satisfying enough to slowly uncover, that it falls into an uncanny valley between playing along as Sherlock Holmes and actually being Sherlock Holmes.

But of course, playing any form of interactive fiction must be an imaginative act on the part of the player, who must be willing to embrace the story being offered and look past the jagged edges of interactivity. Certainly Lost Files is no less interactive than most adventure games, and it offers rich rewards that few can match if you’re willing to not brute-force your way through it, to think about and really engage with its mystery. It truly is a game to luxuriate in and savor like a good novel. In that spirit, I have one final theory to offer you: I think this particular graphic adventure may be especially appealing to fans of textual interactive fiction. Given its care for the written word and the slow-build craftsmanship of its plotting, it reminds me more of a classic Infocom game than most of the other, flashier graphic adventures that jostled with it for space on store shelves in the early 1990s.

Which brings me in my usual roundabout fashion to the final surprising twist in this very surprising game’s history. After its release by a highly skeptical EA, its sales were underwhelming, just as everyone had been telling Christopher Erhardt they would be all along. But then, over a period of months and years, the game just kept on selling at the same slow but steady clip. It seemed that computer-owning Sherlock Holmes aficionados weren’t the types to rush out and buy games when they were hot. Yet said aficionados apparently did exist, and they apparently found the notion of a Sherlock Holmes adventure game intriguing when they finally got around to it. (Somehow this scenario fits in with every stereotype I carry around in my head about the typical Sherlock Holmes fan.) Lost Files‘s sales eventually topped the magical 100,000-unit mark that separated a hit from an also-ran in the computer-games industry of the early- and mid-1990s.

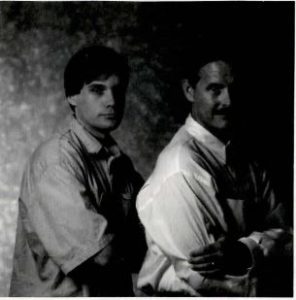

It wasn’t a very good idea, but they did it anyway. R.J. Berg on a sound stage with an actress, filming for the 3DO version of Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes. Pictures like this were in all the games magazines of the 1990s. Somehow such pictures — not to mention the games that resulted from them — seem far more dated than Pong these days.

Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes may not have challenged the likes of John Madden Football in the sales sweepstakes, but it did make EA money, and some inside the company did notice. In 1994, they released a version for the 3DO multimedia console. For the sake of trendiness, this version added voice acting and inserted filmed footage of actors into the conversation scenes, replacing the lovely hand-drawn portraits in the original game and doing it no new aesthetic favors in the process. In 1996, with the original still selling tolerably well, most of the old team got back together for a belated sequel — The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes: Case of the Rose Tattoo — that no one would ever have dreamed they would be making a couple of years before.

But then, almost everything about the story of Lost Files is unlikely, from EA of all companies deciding to make it — or, perhaps better said, deciding to allow it to be made — to a bunch of first-time adventure developers managing to put everything together so much better than many established adventure-game specialists were doing at the time. And how incredibly lucky for everyone involved that such a Sherlock Holmes devotee as R.J. Berg should have been kicking around writing manuals for EA, just waiting for an opportunity like this one to show his chops. I’ve written about four Sherlock Holmes games now in the course of this long-running history of computer gaming — yet another measure of the character’s cultural ubiquity! — and this one nudges out Riddle of the Crown Jewels to become the best one yet. It just goes to show that, no matter how much one attempts to systematize the process, much of the art and craft of making games comes down to happy accidents.

(Sources: Compute! of April 1993 and June 1993; Computer Gaming World of February 1993; Questbusters of September 1988 and December 1992; Electronic Games of February 1993. Online sources include Elinor Mavor’s remembrances of the making Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes, the comprehensive Game Nostalgia page on the game, the Stay Forever podcast episode devoted to the game, Joe Pranevich’s playthrough for The Adventure Gamer, the archived version of the old Mythos Software homepage, and Jason Scott’s “Infocom Cabinet” of vintage documents.

Feel free to download Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes from right here, in a format designed to be as easy as possible to get running under your platform’s version of DOSBox or using ScummVM.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | There have been occasional questions about the extent to which Sherlock Holmes and his supporting cast truly are outside all bounds of copyright, usually predicated on the fact that the final dozen stories were published in the 1920s, the beginning of the modern copyright era, and thus remain protected. R.J. Berg remembers giving “two copies of the game and a really trivial amount of money” to Arthur Conan Doyle’s aged granddaughter, just to head off any trouble on that front. When a sequel to Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes was published in 1996, no permission whatsoever was sought or demanded. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Scott Mavor died of cancer in 2008 |

Brent Ellison

October 12, 2018 at 4:59 pm

One relatively modern public domain “character” that is approaching Holmes’ notoriety these days is Cthulhu. In fact, there are probably more Lovecraft games than Holmes ones on Steam these days.

Jonathan Badger

October 12, 2018 at 5:37 pm

And with Frogwares’ “Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened” there’s at at least one game that actually has both Holmes and Cthulhu!

Jimmy Maher

October 12, 2018 at 7:53 pm

There’s actually some question as to whether Lovecraft’s work is in the public domain. Most of his stories were published after 1922. Others probably know more about this than me, but I believe that the Arkham House Press’s official position is still that they are the only rightful keepers of Lovecraft’s legacy, which was passed to them through August Derleth, Lovecraft’s young friend and, he claimed at least, his duly appointed literary heir. In practice, though, the paperwork is unclear at best and Arkham House isn’t big enough to make a real issue of it in court, so everything has been left in a muddle for decades.

Regardless, Cthulhu has a long way to go catch up to Sherlock Holmes. While Lovecraft has become an icon of certain segments of pop culture, lots and lots of people still have no idea who he is. My American father and my German in-laws all know Sherlock Holmes; I can guarantee you they have no idea about Lovecraft.

Laertes

October 13, 2018 at 11:55 am

I think the copyright system is a big hurdle. Why should anyone be paid today for works whose author has been dead for decades? Sorry, earn your living everyday as most of us do.

Or why should the copyright owners stop anyone who wants to create something based in their work after so many years? The reason of course is money, and avoiding being put to shame if someone makes something better than you with your IP.

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 12:05 pm

I agree. The loss of a cultural commons that results from perpetual copyright is to the profound detriment of everyone.

Julio Morales

November 12, 2018 at 2:56 pm

In Spain copyrights last for 80 years, and in Mexico it seems for 100. After that, they become public domain. However I’m pretty sure there must be an international consent about it!

matt w

October 15, 2018 at 3:34 am

Why should anyone be paid today for works whose author has been dead for decades?

In the US at least, the answer appears to be that the term of copyright is always extended whenever the earliest Mickey Mouse cartoons are about to enter the public domain.

Elzair

October 16, 2018 at 3:48 am

Referring to Cthulhu as “he” is a little weird. “It” sounds better.

Heather L

February 18, 2025 at 6:42 am

On the topic of Lovecraft copyright, well, Arkham House just lied for decades. The inheritor of his copyrights, per the details of his only legally recognized will, was one of his elderly aunts, and when that aunt died it passed to her two descendants, who gave Arkham House explicit legal permission to print the works but did not transfer copyright.

And those heirs conspicuously did not file to renew the copyrights themselves at any point. In those days you got 28 years on a work without renewal, meaning the latest any tales fell out of copyright in the US would be the mid-60s. There have been occasional legal threats from Arkham House since then but they haven’t ever proven they renewed the copyright themselves.

Hope this helps clarify things.

Not Fenimore

October 12, 2018 at 4:59 pm

As a fellow James Cooper (see username), I have to note that either you or Ardai mispelled “Fenimore” in the review transcription. ;)

Jimmy Maher

October 12, 2018 at 7:55 pm

Thanks!

Infinitron

October 12, 2018 at 5:23 pm

But I do find it intriguing that these sorts of complaints keep turning up so often in the case of this specific game, and that they’re sometimes voiced even by critics generally friendly to the genre.

That’s not a huge mystery, is it? The illusion of agency and interactivity is easier to maintain when you’re dragging around items in a physical puzzle-based adventure game then when you’re clicking on lists of dialogue options.

Tellingly, the few places where it fails to do so are the weakest parts of the game.

Lost Files does its level best to resist the siren call of the trivial puzzle, and, with only occasional exceptions, it succeeds.

I’m curious to know what you thought these exceptions were.

Jimmy Maher

October 12, 2018 at 8:00 pm

The whole business about the little boy and the gyroscope is the one that springs to mind…

Infinitron

October 13, 2018 at 8:29 am

I remember being stuck for the longest time on what in retrospect sounds like a very simple puzzle – using a hook to pull the killer’s cufflink out of a barrel.

I think the problem is that the game was such smooth sailing most of the time that it didn’t train you to think that way.

Another interesting thing about the game is that there’s an entire investigative branch, including unique areas, that turns out to be a complete red herring. If I recall correctly, it dead-ends at a department store where a romantic admirer of the murder victim works. He had nothing to do with her death.

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 9:11 am

Yes, that’s definitely another one.

Such blind alleys as this are a staple of mystery novels and television, but not so much mystery games. It’s another way that Lost Files feels like the rare interactive mystery that’s faithful to the (literary) genre. The board game Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, which I still consider the gold standard for this sort of thing, is full of them as well.

Jonathan Badger

October 12, 2018 at 5:27 pm

Finding someone who has actually read and enjoyed the writing of Edgar Rice Burroughs, James Fennimore Cooper, or Arthur Conan Doyle requires the patience of Diogenes. Most people know the character from television and the movies, at best

Really? While there is some truth to this for Fennimore Cooper (I found “Last of the Mohicans” to be nearly unreadable despite enjoying the Daniel Day-Lewis film, and even Mark Twain thought the same in the 19th century itself), it isn’t hard at all to read Conan Doyle or Burroughs — I went through a Sherlock Holmes phase in my teens myself.

Jimmy Maher

October 12, 2018 at 8:01 pm

As I said, one almost hates to puncture it with facts… ;)

Charles Ardai

December 5, 2018 at 8:02 am

What a terrific article! It’s a pleasure to be a part of it, in however small (and refuted) a fashion.

Looking back on what I wrote, I can’t think myself why I wrote that fans of Burroughs’ and Doyle’s writing were hard to find. Certainly people continue to read Doyle at a reasonable clip, and as a boy I read all three with pleasure. Sometimes when you’re writing on deadline and in love with the sound of your own typewriter, you write some profoundly stupid things.

That said, I continue to feel this game was a disappointment, and that’s coming from someone who enormously enjoyed Infocom text adventures. I’d rather play INFIDEL or PLANETFALL or SORCERER or THE WITNESS than this game any day. I’d have to replay it to remember exactly why, but I do remember, all these years later, just not having nearly as much pleasure pointing and clicking my way through this one.

I’m happy, though, that in the end it did well for its creators, in spite of the bludgeoning I gave it.

Jimmy Maher

December 5, 2018 at 9:33 am

Thanks for this! As I said in the article, I always enjoy your pieces for Computer Gaming World when I revisit them in the course of my research, even as I suspect we have somewhat different tastes and priorities when it comes to games. I’m happy you’ve gone on to such a productive career in letters.

anonymous

October 12, 2018 at 5:58 pm

> The only characters with a remotely similar degree of recognizability who postdate him are the Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan, and neither of them presents writers with quite the same temptation to tell new story after story after story.

Well… I wouldn’t say that the Wizard of Oz himself is a highly recognizable character, but everyone seems to know the Judy Garland movie at least, and the basic story. That having been said, there are a zillion Oz books, more than a few movies and tv adaptations, and if none of those have been tremendously successful besides the one from the 30s, the Wicked musical (based on a revisionist prequel book) has been huge. And is getting a movie next year.

Many of the books are out of copyright, and they’re not bad, though they tend to be weird. Give ‘em a shot.

Kroc Camen

October 12, 2018 at 7:57 pm

Yes! Love this game! It was a real pleasant surprise, and it’s shocking that so few adventure games before or since have come as close to the perfect mystery-adventure design. Here’s my review April 2016 so you can see how it compares against your observations of the unusual critical history the game has.

—

A murder-mystery is pretty much perfect material for a point-and-click adventure, and Sherlock Holmes is the go-to character for the job — out of copyright, universally known and timelessly Victorian. Much crap has had the Sherlock Holmes name attached to it and still he has come out unscathed. This 1992 adventure game by Mythos succeeds by way of many great qualities.

The plot is good and becomes increasingly complex and engrossing. The writing is of high quality with an astonishing amount of period detail. There are many locations in the game and they open up to you at a quick pace, always providing something new to see.

The art style is a controversial point. Some reviewers have called it grainy and indistinct. The whole game is done in a 1930s art-poster style (which had become en-vogue during the ’90s); whilst I don’t have my CRT set up at the moment, I believe that the graininess and indistinct contrast would look fundamentally clearer and more evocative on the superior colour, deeper blacks and slight fuzziness of a CRT. Personally, I’m a fan of the art style and find it another aspect of the game to enjoy.

The games puzzles are not obtuse and the lack of combining inventory items thankfully removes a large headache of other adventure games (rubbing everything against everything else in the hope of progress). Such a requirement would make the game impossible because the game simply accumulates inventory like it was gold being handed out for free. Almost nothing you receive every goes away again, leaving you carrying around half of London in your pocket. It doesn’t prove to be a problem though as often the item you need to use will the be the one you most recently received, or if not, hopefully obvious enough.

I’d definitely recommend this game to any adventure game / Sherlock Holmes aficionados.

:: Highlights

* Excellent script and descriptions

* Lots of places to visit

:: Areas of Improvement

* Inventory bloat

* Only uses the chemical analysis / Baker Street Irregulars features once. These aspects could really have done with being featured more often throughout the game

Oded

October 12, 2018 at 8:41 pm

Typo – “doesn’t go so far as the forgo the deerstalker” that first “the” should be a “to”?

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 7:45 am

Yes. Thanks!

Ronan

October 12, 2018 at 9:07 pm

Here’s a game that should definitely be on GOG.

David Boddie

October 12, 2018 at 9:27 pm

“The only characters with a remotely similar degree of recognizability who postdate him are the Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan, and neither of them presents writers with quite the same temptation to tell new story after story after story.”

And it can be a tricky situation when it comes to copyright and Peter Pan: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_and_Wendy#Copyright_status

Tom

October 12, 2018 at 9:56 pm

As a side note, Berg’s characterization of Holmes as “arrogant, a misogynist, and extremely smug” is in error in one regard–Holmes is not so much a misogynist as he is a misanthrope.

In that regard, one may hold Doyle responsible for the raft of characters who should honestly never be allowed in public but are too competent not to use that we see in today’s entertainment, few of which are executed as well as Holmes is.

Pedro Timóteo

October 14, 2018 at 3:20 pm

The “Holmes is a jerk” characterization, while adopted by modern interpretations (Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, Elementary, and the two movies with Robert Downey Jr.), was, IMO, actually mostly restricted to the very early Holmes stories in the canon, especially A Study in Scarlet. That story’s Holmes, famously, is so obsessed with not “occupying” his brain with any information not related to detective work that he isn’t aware that the Earth goes around the Sun, and, when told about that, announces that he’ll do his best to forget it. Later stories, however, have Holmes quoting artists, philosophers, and so on. Doyle, most likely, intended to use Holmes for that story alone and was surprised by his popularity, so he had to “humanize” the character for him to work well in a series of short stories.

Jimmy Maher

October 14, 2018 at 3:37 pm

This phenomenon — call it filing down a character’s sharp edges — is super common in serial fictions of all stripes. In the context of games, see how Leisure Suit Larry goes from being a skeezy outcast to being a lovable loser, downright cute in an “aw, there the little fellow goes again…” sort of way, over the course of that series.

Gnoman

October 18, 2018 at 2:26 am

Even in A Study In Scarlet, Holmes wasn’t the arrogant donkey that he’s often played up as. There’s some sense of superiority there, but it is primarily directed at Scotland Yard rather than humanity as a whole – which makes a lot of sense. Holmes, particularly at this point in the canon, looks down on the police because their inept methods make a mockery of his Great Calling – he’s turned criminology into a science, while they’re just blundering about like idiots because they have no idea of his methods..

_RGTech

July 16, 2025 at 5:43 pm

You always need some room to develop your characters. Thus the movies and series happily use the given starting point, and interaction with others (and Watson) changes him.

Ross

October 12, 2018 at 10:30 pm

Also, there’s a command-line option to just play the darts minigame.

Jeff Morris

October 13, 2018 at 2:16 am

I would to see a series of articles on Computer Gaming World, decade by decade.

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 7:50 am

It’s an interesting story, certainly. The magazine was founded by a former Baptist pastor, then edited for years by the son of another one. That alone makes it intriguing. Will take it under advisement, as they say. ;)

Lisa H.

October 13, 2018 at 4:31 am

Holmes in his armchair before a roaring coal fire

Do coal fires “roar”?

Mayhaym

October 14, 2018 at 10:10 pm

My thought exactly!

Aula

October 13, 2018 at 11:14 am

“A dark purple silk dressing down”

Either someone wrote a letter of reprimand on a piece of silk, or that should be “dressing gown” instead.

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 12:03 pm

Thanks!

Ibrahim Gucukoglu

October 13, 2018 at 2:29 pm

Has anyone discovered whether the lost files can be played on a modern Windows system? Still further, has anyone been made aware of whether it can be rendered playable with a screen reader as I’d like to get my teeth into this one. I’ve played through Sherlock, the Riddle of the Crown Jewels and 221B Baker Street which was ported to AGT as part of the masters edition, but have had limited success with other titles in the Sherlockian IF cannon, partly because many of them were written in proprietary formats which aren’t playable with modern IF interpretors, even if they will run on Windows. Thanks in advance for any input on this one.

Kroc Camen

October 13, 2018 at 5:03 pm

The game can be played by SCUMMVM which works on a multitude of platforms and has options for enabling subtitles, but I couldn’t tell you if it exposes them in an accessible way.

Martin

October 13, 2018 at 4:13 pm

So what about the sequel? Is it worth playing too?

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 5:19 pm

Haven’t played it yet…

Carlton Little

October 13, 2018 at 6:06 pm

You don’t know what you’re missing!

It is a fantastic game, by and large. Will you cover it?

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2018 at 6:29 pm

Given its pedigree, I’m sure I will, assuming we get that far.

Martin

October 17, 2018 at 7:23 pm

Of course we’ll get that far :)

Sniffnoy

October 14, 2018 at 2:50 am

Some editing nitpicking:

9 orders of magnitude is already a factor of a billion. However you’re measuring, countless orders of magnitude seems a bit much. “Multiple orders of magnitude” or “several orders of magnitude” would be enough to be a huge difference.

Jimmy Maher

October 14, 2018 at 7:25 am

Thanks!

Hallie Miles

October 14, 2018 at 1:34 pm

This game also works fine under SCUMMVM. Point it to the “holmes” directory, then make sure that you select “Creative Music System Emulator” or (if you have the ROMs) “MT-32” on the Audio tab.

Pedro Timóteo

October 14, 2018 at 3:30 pm

ScummVM’s “Creative Music System Emulator”, for this game, actually seems to enable MT-32 music (at least on my ScummVM installation, with the MT-32 ROMs available). You probably meant “Adlib Emulator”, which is probably the best option if you don’t have the ROMs. (According to INSTALL.EXE, the game only supports Adlib/Soundblaster and MT-32 for music, plus Soundblaster and Tandy DAC for digitized sounds.)

Alex Freeman

October 15, 2018 at 5:42 am

That’s actually a common criticism of point-and-click adventure games in general and is why I prefer parser-driven ones.

Ben P. Stein

October 17, 2018 at 1:27 am

Great post!

I noticed a very minor typo:

“ostensibly serious adventure game” —> games

Jimmy Maher

October 17, 2018 at 6:22 am

Thanks!

RavenWorks

October 23, 2018 at 12:18 am

For the record, when I use the provided copy of the game with dosbox in the manner described in the readme, I consistently get a freeze the moment the bottle is broken by the cat in the intro, with the DOSBox Status Window printing “Exit to err:r DMA segbound wrapping (read)”. This happens even in a clean install of DOSBox 0.74-2, on Windows 10.

Running it in ScummVM seems to be working fine, though!

Jimmy Maher

October 23, 2018 at 8:29 am

Strange, but it looks like the problem isn’t unheard of: https://www.dosbox.com/comp_list.php?showID=83&letter=L. Setting “core” to dynamic in the config file might fix it, or as a last resort manually setting the process affinity to one core in the Task Manager after it starts running.

Or just use ScummVM, of course. ;) Noted that it works there in the article as well.

Patai Gergely

March 30, 2019 at 8:24 am

Earlier versions of DosBox also work fine. I played with 0.73, for instance.

Christopher Benz

December 27, 2018 at 11:10 am

I’m enjoying these articles as much as ever, thanks for producing such well written and researched accounts.

A tiny bit more nitpicking in the interests of perfection – you may want to revisit your observation that the deerstalker cap only appears once in Paget’s illustrations – from SP’s wikipedia page:

“Paget is also credited with giving the first deerstalker cap and Inverness cape to Holmes, details that were never mentioned in Arthur Conan Doyle’s writing. The cap and coat first appear in an illustration for “The Boscombe Valley Mystery” in 1891 and reappear in “The Adventure of Silver Blaze” in 1893. They also appear in a few illustrations from The Return of Sherlock Holmes. (The curved calabash pipe was added by the stage actor William Gillette.)”

Christopher Benz

December 27, 2018 at 11:14 am

An example from Silver Blaze (it actually occurs in at least 4 illustrations in this story alone) – https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=File:Illus-silv-paget-01.jpg

Jimmy Maher

December 28, 2018 at 9:18 am

Thanks so much for this! Edit made. ;)

Christopher Benz

January 7, 2019 at 10:48 am

Good edit. Your original point still stands that the cap wasn’t made iconic by the original texts. That was to come later as you have outlined.

Gigantes

January 15, 2019 at 2:44 pm

I enjoyed the review and with some enthusiasm, decided to play the game through via browser emulator. I finished just a few moments ago. Note that I’ve read all of Doyle’s Holmes canon and particularly enjoyed the Jeremy Brett – BBC adaptations.

I agree with you that the game is nicely conceived and executed, although I do think there’s some real merit in the critiques you cited. The game seemed linear to the point that I was simply stumbling around in search of a predetermined solution. Other than spending a lot of time moving back and forth between locations and re-attempting conversations and inspections, there wasn’t a terribly dynamic feel to the game, nor to the puzzles. There were also plenty of minor points where the game could get arbitrarily hung up, with no further progress possible until the issue had been (sometimes accidentally) addressed. An example– at a certain point Toby the dog’s services are required, but seemingly the only way to unlock the location is to talk to Watson, who prompts Holmes about the possibility. Holmes of course never would have needed that kind of prompt IMO, and it was frustrating needing to stumble upon those kinds of ‘solutions’ as often I needed to. This kind of problem of course is common for the genre, but one wants some suitable compensation… some other area of the game to shine, or charm, or so forth.

I would guess the game was more impressive at the time on multiple levels, and I say that as an 8-bit enthusiast who tends to prefer simplicity in graphics and design. Maybe it just hasn’t aged particularly well. Maybe it’s just me. Certainly the graphics are lovely and the historical detail is impressive, but it feels to me like the adventure is rather needlessly prolonged, without much liveliness, adaptability, or richness of puzzles to make it as interesting as something like a LucasArt game from this same period, for example. I suspect this is a nice game and a fine effort in terms of Holmes entertainment, but more of a B-lister when it comes to this specific type of graphic adventure.

Leo Velles

February 12, 2019 at 5:15 pm

Hi Jimmy, i find your blog through the adventure gamer, which i´m reading chronollogically. That will take a few months i guess, and now even more, because i will do the same with your blog, which is amazing, it´s a real encyclopedia. First time i get to your blog was from an the adventure gamer link from the hitchiker’s guide to the galaxy and read your Douglas Adams story with great delight, eventhough i knew nothing of him. That shows what a great writer you are. And now, eventhough i decided to read your blog in the proper order, i cheat and skipped just to read your fellings about this game, which is my favourite adventure game of all time. I become in love with adventure games since i played Maniac Mansion in a C64 back in 1988, that game is in my heart, but The Lost Files is superb in every way, the plot (kidnapping, murder, suicide, blackmail…) and the atmosphere, the graphics (i still find today the work whith the ligthing and shadows as a masterpierce). Anyway, i’m from Argentina and my english isn’t as good as i wish, at least for writing, but i want to tell you that you are making a hell of a good work and i will be reading every entry until i catch up.

Cheers!

Wolfeye M.

October 23, 2019 at 7:38 am

“Finding someone who has actually read and enjoyed the writing of Edgar Rice Burroughs, James Fenimore Cooper, or Arthur Conan Doyle requires the patience of Diogenes.” Never heard of Cooper, but I do enjoy Doyle and Burroughs, and two out of three ain’t bad.

“These are adventure stories narrated from the perspective of Dr. Watson.”

That explains a lot. I don’t typically enjoy mystery stories, Agatha Christie’s and Edgar Allen Poe’s books being exceptions. If I find myself reading a “whodunnit”, I read it, I don’t try to solve it. But, now, I wonder if Christie’s and Poe’s stories are like Doyle’s… An Adventure story about someone solving a mystery, rather than a whodunnit.

I’m intrigued enough by the game, thanks to your glowing review, that I might make it an exception to two of my rules. I don’t play Adventure games, because I don’t usually enjoy them, and I don’t play EA games, because I’m boycotting them. But, the game sounds fun, and not the usual EA game.

Nice that you have the game available for download, so I don’t have to give EA my $ to play it.

Rafael M.

January 23, 2020 at 12:01 pm

Where is the article on the rose tattoo? :) I’m playing it now and would be curious to know what you think. While it has many flaws, I enjoy the dialogue and the voice acting, and the complexity and scale of the game keeps me coming back to see what it has in store for the next twist.

Jimmy Maher

January 23, 2020 at 2:19 pm

Someday!

CaesarZX

May 31, 2020 at 4:15 pm

That picture of all 5 members of Mythos Software has a wrong legend text, the correct one should be: Back, Left to Right: David Wood, Eleanor Mavor and Scott Maver; Front, Left to Right: James Fergusen, John Dunn.

CaesarZX

May 31, 2020 at 4:17 pm

Opps, Scott *Mavor

Jimmy Maher

June 1, 2020 at 9:06 am

Thanks!

HIred Goon

January 18, 2022 at 6:49 pm

Still haven’t finished this game. Currently playing with Dosbox through D-fend as my front end (Dosbox 0.74 seems to cause the game to freeze up, Dosbox 0.73 works fine though)

Jonathan O

September 4, 2022 at 2:40 pm

Maybe you should check the spelling of the word “pixilated” in the quote by Rose Mavor – I think, in that spelling, it actually means “drunk”, although this could be a US/UK spelling issue.

Jimmy Maher

September 5, 2022 at 7:07 am

Wow. I never knew there was such a word. Thanks!

Jonathan O

September 4, 2022 at 2:44 pm

Sorry – Elinor Mavor, not Rose.

Geraldo Rivera

December 6, 2022 at 9:36 pm

The Best adventure of Holmes , The atmosphere was superb .