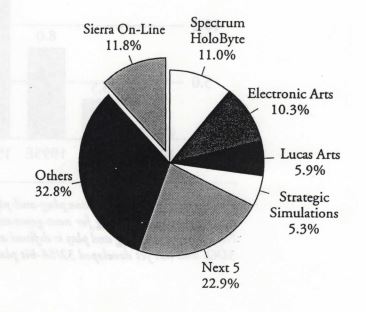

This pie chart prepared by the investment firm Piper Jaffray Research provides a snapshot of the American computer-game industry as of 1993. Sierra leads the pack with a market share of 11.8 percent, trailed closely by Spectrum Holobyte, who have just increased their profile dramatically by acquiring MicroProse Software. Electronic Arts comes in at only third place here, even following their recent acquisition of Origin Systems, but this chart reflects only their computer-game sales; their total sales including computers and consoles are vastly higher than those of Sierra by this point. SSI manages to come in at a respectable fifth place, thanks not least to the two aforementioned acquisitions of comparably sized competitors, but their trend lines are all moving in the wrong direction; their last new release to cross the magical threshold of 100,000 copies sold was Eye of the Beholder from February of 1991, while their biggest game of 1993 will sell just over 70,000 copies.

Two individually unhappy spouses aren’t the recipe for a happy marriage. By 1992, the computer-game publisher SSI and the tabletop-game publisher TSR, whose announcement of a partnership had so shocked both of their industries back in 1987, were learning this reality the hard way. Dungeons & Dragons, both on the computer and on the tabletop, was in trouble, and the marketing synergy which the two companies had so successfully created just a few years before had now turned into a deadly embrace that threatened to pull them both under.

In many ways, SSI’s problems were typical of any small publisher in their changing industry. Players’ audiovisual expectations of the games they purchased were growing rapidly, and it just wasn’t clear where the money to meet them was to come from. SSI had ridden their Gold Box engine for Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs way too hard, churning out nine games using it — eleven if you count two reskinned science-fictional Buck Rogers games — in a span of less than four years. The engine had received some modest improvements over the course of that time, in the form of rudimentary mouse support and VGA- rather than EGA-standard graphics, but at bottom it still played like what it was: an artifact from an entirely different epoch of gaming, designed around the affordances of the 8-bit Commodore 64 rather than the latest 32-bit Intel wonders. It was so outdated as to seem almost laughable beside a boundary-pushing wunderkind like Origin Systems’s Ultima VII.

Just as distressingly, SSI hardly seemed to be trying anymore even when it came to their Gold Box designs. No later Gold Box game had possessed anything like the creative flair of Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds, the first two games of the line and by far the best.

And so, as the technology had aged and design standards had fallen, gamers had reacted appropriately: sales had dropped almost linearly from title to title. Pool of Radiance had sold 264,536 copies upon its release in August of 1988; Dark Queen of Krynn, the anticlimactic end of the Gold Box line, sold 40,640 copies after its release in May of 1992. SSI was still profitable that year, but only by a whisker: during the fiscal year which ended on September 30, 1992, profits amounted to just $168,000 on sales of a little under $13 million, the latter of which fell short of expectations by $1 million. What would the next year bring?

TSR was a larger and more diversified company, but they were facing the same essential problem: sales of their own Dungeons & Dragons line for the tabletop had been going in the wrong direction as well for the past couple of years, and it wasn’t immediately clear how to reverse that trend. A flood of new rules supplements and settings — by 1993, TSR would offer an extraordinary eight separate boxed “worlds” in which to play the game, ranging from traditional high fantasy to the Arabian Nights to the depths of outer space — certainly wasn’t doing the trick. In fact, by making Dungeons & Dragons ever more impenetrable to newcomers, the torrent of product was arguably hurting TSR more than it was helping them.

Thanks to these trends, Dungeons & Dragons was in danger of seeing its position as the commercial ne plus ultra of tabletop RPGs usurped for the first and only time in the history of the hobby. The biggest threat to its status came from a new RPG called Vampire: The Masquerade, whose rules-lite, storytelling-oriented approach was the antithesis of the baggy monstrosity which Dungeons & Dragons had become. By catching a wave of “goth” inspiration that was sweeping pop culture more generally, Vampire had even accrued a degree of street cred the likes of which TSR’s nerdier, more pedantic offerings couldn’t have hoped to match even in their early 1980s heyday. TSR’s entire Dungeons & Dragons gaming line was in danger of becoming the world’s most elaborate loss leader, fueling sales of the one part of their empire that was still consistently earning money: their vast and ever-growing lineup of fantasy novels based on their gaming properties.

Human nature being what it is, it was perhaps inevitable that SSI and TSR, these two partners with good reason to be profoundly worried about their futures, would each come to blame the other for at least some of their difficulties. SSI noted pointedly that the Gold Box line was supposed to have been a creative as well as financial partnership between the two companies, with TSR’s staff contributing much of the content for the computer games and TSR themselves publishing tie-in products for the tabletop. All of those synergies, however, had dried up after Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds. (The status of these two very first games as the very best of their line begins to seem like less of a puzzle in light of TSR’s active involvement with them.) SSI had been left to their own devices from 1990 on, albeit still subject to the frequently exercised veto power which TSR enjoyed over their ideas.

Meanwhile, even as SSI complained about their creative abandonment, it was hardly lost on TSR that the Gold Box engine had fallen badly behind the state of the art. As they judged it, its antiquity had become extreme enough to actively hurt their brand, not only on the computer but on the tabletop as well; when struggling against their tabletop game’s popular image as a kitschy relic of the 1980s, TSR’s marketers weren’t excited to be confronted with computer games that themselves looked like products of the previous decade. TSR was also unhappy with SSI’s failure to port the Gold Box games from computers to consoles; out of all of them, only Pool of Radiance had been ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System, by a Japanese developer rather than SSI themselves. SSI tried to point out that this port, which played badly and sold worse, only served to illustrate all the ways in which this style of game just wasn’t suitable for consoles, but TSR was having none of it. In their view, the porting issue was a problem for SSI to solve rather than to explain away.

Behind all the bickering loomed a daunting reality: SSI’s exclusive license to Dungeons & Dragons was due to expire on January 1, 1993. One of the partners had far more cause for concern about this fact than the other. For those in the boardroom at TSR, the question of the contract’s renewal was just another business debate to be hashed out, but for SSI it was quite possibly of existential importance. After signing his first contract with TSR, Joel Billings, SSI’s founder and president, had rejiggered the public and private face of his company, from that of a maker of hardcore wargames inspired by the tabletop grognard tradition of Avalon Hill and SPI into the Computerized Home of Dungeons & Dragons. While SSI still published some wargames in the early 1990s, they generally sold even worse than the final stragglers from the Gold Box line, and were made strictly by outside developers; almost the entirety of SSI’s internal development efforts had been devoted to Dungeons & Dragons for the past five years. SSI’s identity had become so bound up with TSR’s flagship property that it wasn’t clear what they could or should be without the Dungeons & Dragons license.

The uncertainty surrounding the future of the contract left SSI paralyzed. It was obvious that they needed a better, more modern engine if they were to continue to make Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs, but it would be foolhardy to embark on that expensive project before they were sure of retaining the license that would let them use it for its intended purpose.

Thus Billings must have breathed a sigh of relief in early 1992, when TSR, despite all their recent misgivings about SSI’s handling of the license, agreed to an eighteen-month contract extension. It would take the license out to July 1, 1994, giving SSI enough time to make a new engine and at least one new game with it. Still, the short length of extension served notice that they were on probation; if the marriage was to continue, SSI would have to deliver a hit of Pool of Radiance proportions.

Billings put his people to work on an engine that would build upon the best ideas of SSI’s competitors, not least Origin’s much-admired Ultima VII engine. Like that one, this one would be designed with a mouse in mind from the start; would offer free-scrolling real-time movement over a large world; would go almost entirely mode-less in terms of interface, integrating combat into the same view where conversation and exploration took place. Gone would be the fussy paragraph books, graph-paper maps, and code wheels of the Gold Box games, which could make the experience of playing them feel almost like a hybrid between a computer and tabletop game. SSI had a very different experience in mind this time out. They planned to make the engine effortless enough for the player that it could be ported to the Super Nintendo for play on living-room couches. And if that version did well, other console ports would follow.

TSR, eager to give a boost to one of their sales-challenged alternate settings, convinced SSI to set the first game made with the new engine in the land of Dark Sun, a desert world with a vaguely post-apocalyptic feel. Billings, aware that he was on shaky ground with TSR, also initiated development of an original science-fiction game that was to use the engine as well, just in case the Dungeons & Dragons license went away.

Creating such a complex engine alongside the first two games to use it was a truly enormous task — by far the biggest thing SSI had ever attempted, dwarfing even the initial software engineering that had gone into the Gold Box engine. Development dragged on and on after the Gold Box line had petered out with Dark Queen of Krynn. SSI attempted to plug the Gold Box-sized gap in their product line with such second-string releases as Prophecy of the Shadow, an internally developed, non-licensed CRPG-lite (25,875 copies sold); Pirates of Realmspace, a buggy computerized take on TSR’s Spelljammer setting from an outside developer known as Cybertech (23,280 copies sold); The Summoning, a simple action-RPG from Event Horizon Software (25,273 copies sold); Veil of Darkness, a game of a similar stripe to the previous from the same developer (9866 copies sold); Legends of Valor, a poor man’s Ultima Underworld from Synthetic Dimensions (12,588 copies sold); and Unlimited Adventures, a final hurrah for the Gold Box in the form of a public release of many of SSI’s internal development tools, thereby to let the diehards make more games of their own of the old type (32,362 copies sold).

As the sales figures above attest, none of these games set the world on fire. Indeed, their sales managed to make even the latter days of the Gold Box line look pretty good by comparison. In all, SSI released just three games between the summers of 1992 and 1993 that managed to top 40,000 units: Great Naval Battles in September (43,774 copies sold), Tony La Russa Baseball II in March (70,902 copies sold), and Eye of the Beholder III in May (50,664 copies sold). Of this trio, only the last was a Dungeons & Dragons title, and only the last was developed internally. Needless to say, the bottom line suffered. During the fiscal year which ended on September 30, 1993, revenues fell to $10.5 million, and the company lost $500,000 — the first annual loss SSI had posted in more than a decade.

Joel Billings wrote in that year’s annual report that it had been “the most difficult year in SSI’s 14-year history.” He spoke his personal truth not least. Throughout this period, over the course of which development of the Dark Sun game and its engine kept dragging on far longer than expected, Billings was scrambling madly to stem the bleeding. He put an organization that had always had the atmosphere of a family company through the trauma of its first-ever layoff, slashing the employee rolls from 115 to 75 employees; the memory of doing so still haunts Billings, a gentle soul at heart, to this day. Having been forced to cut the staff needed to create the science-fiction game earmarked for the new engine, he cut that as well, putting all his eggs into the single basket that was the Dark Sun game. Even the Super Nintendo version of that game, which his programmers had been struggling mightily to realize, would have to be set aside as well, at least for now. Much to TSR’s chagrin, this latest Dungeons & Dragons game too would have to live or die on computers.

Yet all of Billings’s scrambling constituted no more than financial triage. The existential obstacle which SSI faced was that of being a small, boutique publisher in an industry whose economies of scale were making it harder and harder for such an entity to survive. It was getting ever harder to win shelf space at retail, harder to pay for advertising in the glossy magazines — and, most of all, harder to foot the ever-increasing bill of developing modern games that met all of the expectations of the 1990s. Billings reluctantly concluded that he had but one choice: he had to sell out, had to find a buyer for the family business he had spent almost a decade and a half building from the ground up.

Accordingly, he spent much of his time in 1993 beating the bushes for just such a buyer. Yet here he was stymied once again by the realities of the marketplace. SSI was far from the only small publisher looking for a port in the storm, and many of the others had — or at least were judged to have — more attractive portfolios of extant and forthcoming games. Thus Billings faced a dispiriting, borderline-humiliating series of near misses, of seeing SSI cast aside in favor of alternative acquisitions in the fast-consolidating industry.

At the beginning of June, he thought he had made a deal with Spectrum HoloByte, an oddly bifurcated publisher that was almost entirely dependent on two wildly divergent games: the ultra-hardcore flight simulator Falcon, whose manual was roughly the size of a Tom Clancy novel, and the casual phenomenon Tetris, a game so brilliantly simple that it took only about 30 seconds of experimentation at the keyboard to spawn a lifetime’s addiction. Both of these games, radically different though they were in personality, were equally successful with their own demographics. Just as importantly, Spectrum HoloByte was absurdly well-connected with the movers and shakers of international finance, and was awash in venture capital as a result.

Due diligence between SSI and Spectrum HoloByte was completed, and a plan was made to meet again and sign a letter of intent as soon as that year’s Summer Consumer Electronics Show was behind both of them. At that show, however, Spectrum HoloByte met with Microprose, whose financial circumstances were even more desperate than those of SSI but who had a much more impressive array of upcoming titles to show to potential suitors. To make a long story short, Spectrum HoloByte bought MicroProse instead, leaving SSI stranded at the altar.

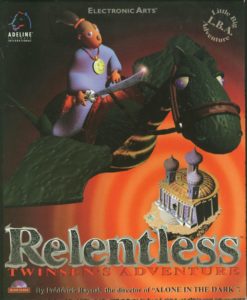

A few months later, the same scenario repeated itself. This time the would-be acquirer was Electronic Arts, a company with which SSI already had a longstanding relationship: Trip Hawkins had been a member of SSI’s board since before he founded EA, SSI had been piggybacking on EA’s distribution network as an “affiliated label” since 1987, and EA in fact already owned 20 percent of SSI thanks to an investment made in 1987, when the smaller company was first scaling up to take on Dungeons & Dragons. For all these reasons, the deal at first seemed a natural one. But Hawkins, the biggest proponent of the acquisition on EA’s side, was busy with a new semi-subsidiary known as 3DO and no longer had the day-to-day involvement necessary with the parent company to push it through. After kicking the tires a bit, the rest of EA’s management decided that SSI just wasn’t worth the asking price — especially given that EA already owned Origin Systems, one of SSI’s biggest rivals in CRPGs. Contrary to Joel Billings’s best intentions, SSI would thus be forced to exit 1993 as they had entered it: still an independent company, facing a future that looked more perilous than ever.

SSI’s struggle to find a buyer was a sign not only of their own weakness but of the diminished commercial profile of Dungeons & Dragons. Five years earlier, three quarters of the industry would have rushed to scoop up SSI, if only to acquire the enviable licensing deal they had recently signed. Now, though, the tabletop game was at a low ebb of its own, even as it seemed hopelessly antithetical to all of the winds of change in digital gaming. Where did this nerdy game played in parents’ basements, all tables and charts and numbers, fit in an industry rushing to make slick, kinetic interactive movies featuring real Hollywood actors? Dungeons & Dragons just wasn’t cool. It had never really been cool, of course, but that hadn’t been a problem when the computer-game industry as well was thoroughly uncool. But now, as computer-game moguls were busily penning paeans to themselves as the next wave in mainstream entertainment, its uncoolness was extremely problematic.

Amidst all of this — in September of 1993, to be specific — Dark Sun: Shattered Lands finally got completed and released. It was the most important game SSI had published since Pool of Radiance; the future of the TSR partnership, and thus their own future as a company, rode on its success or lack thereof.

When viewed separately from all of these external pressures, as just a game to be played and hopefully enjoyed, it revealed itself to be a nobly earnest attempt to improve on SSI’s most recent efforts in the realm of CRPGs, even if it wasn’t an entirely unblemished one. On the technological side, SSI’s next-generation engine largely delivered where it needed to: it was indeed vastly slicker, prettier, easier, and more modern than the Gold Box engine, feeling like a true product of the 1990s rather than a holdover from the last decade. It was an engine that could even stand next to the likes of an Ultima VII without undue embarrassment. Indeed, SSI seemed to have learned from their rival’s mistakes and done Origin one better in some places. For example, in place of the real-time, well-nigh uncontrollable frenzy that was combat in Ultima VII, SSI’s engine lapsed seamlessly into a turn-based mode as soon as a fight began; this allowed combat in Shattered Lands to retain most of the tactical complexity and interest that had marked its implementation in the Gold Box games, with the additional advantages of increased audiovisual interest and a less cryptic interface.

At the same time that they endeavored to keep combat interesting, however, SSI’s design team had clearly made a concerted effort to move beyond the exercises in incessant combat and very little else which the Gold Box games had become by the end. Shattered Lands offered much better-developed characters to talk to, along with heaps of real choices to make and alternative pathways to discover. The new approach was enough to impress even so committed an SSI skeptic as Scorpia, Computer Gaming World magazine’s longtime adventure columnist, who had been roundly criticizing the Gold Box games in print for their “incessant, fight-after-fight” nature for half a decade by this point. Now, she could write that “SSI is taking their role-playing line in a new direction, which is good to see”: “the solution to every problem is not kill, kill, kill.” Shay Addams, another prominent adventure pundit, had a similar take: “It’s no secret that I never liked the Gold Box games. Dark Sun, however, kept me coming back to the dungeon for more: more combat, more exploring, more story.”

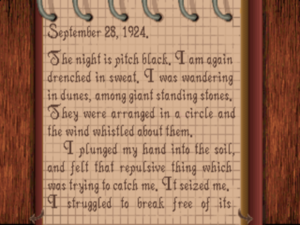

Still, the game had its fair share of niggles — more than enough of them, in fact, to prevent its achieving a classic status to rival Pool of Radiance and Curse of the Azure Bonds. While SSI was to be commended for attempting to give the setting and plot more nuance and texture, that just wasn’t the sort of thing they did best, and they were still receiving little to no help from TSR on that front. The writing and plotting were derivative in several different directions at once, hackneyed even by the usual standards of the genre. Mind you, the writing wasn’t actually worse than most of that which had accompanied the Gold Box games — but here, moved as it was from a paragraph book onto the screen and expected as it was to do a lot more heavy lifting, its weaknesses were magnified.

Shattered Lands was also damaged as a computer game by its need to conform to TSR’s tabletop rules. The boxed set which presented the Dark Sun setting for the tabletop included a whole range of new rules complications and variations to distinguish it from the already convoluted Dungeon & Dragons base game, and most of these SSI was expected to implement faithfully as part of their licensing agreement. And so Shattered Lands came complete with a bunch of races and classes unfamiliar even to most Gold Box and tabletop Dungeons & Dragons veterans, along with a veritable baseline expectation that every character would be double- or triple-classed. Clerics suddenly had to choose an “element” to worship, which limited their selection of spells — and now everyone had access to a whole parallel sphere of magic known as psionics, and had to choose a specialty there as well. No game designer starting a CRPG from scratch would ever have inserted so much cruft of such marginal utility to the ultimate goal of fun; it was the sort of thing that could only arise from a company like TSR throwing rule after rule at the wall over the course of years in order to sell more supplements. Certainly none of it made much sense in a game explicitly envisioned as a new beginning for Dungeons & Dragons on computers, a place for fresh players to jump aboard. Nor, for that matter, did the choice of the oddball world of Dark Sun as a setting; for all that critics like me have long railed against the tendency, gamers for time immemorial have been demonstrating their preference for CRPGs set in generic high-fantasy worlds — such as that of TSR’s own Forgotten Realms, home of the most commercially successful of the Gold Box games — over more unique settings like this one.

But whatever its intrinsic strengths and weaknesses, Shattered Lands suffered most of all from one undeniable external failing: it was deeply, thoroughly unfashionable in the context of 1993. At a time when the whole industry was moving toward multimedia “talkies,” its many conversations and descriptions were still implemented via screenful after screenful of boring old text. And in addition to the old-fashioned implementation, there also remained the fact that the Dungeons & Dragons name just wasn’t the force it once had been. A measure of the industry’s attitude toward the game and its commercial prospects can be gleaned from its placement in the magazines. Even as they were giving it reasonably positive reviews, Computer Gaming World buried it on page 124 of 276, Shay Addams’s Questbusters newsletter on page 8 of 16. (The lead review of that issue, evidently judged to be more immediately interesting to the newsletter’s readers than a review of Shattered Lands, was of Legend Entertainment’s Gateway 2, a fine game in its own right but one which still had a parser, for God’s sake.)

So, you’ve probably guessed where this is going: Dark Sun: Shattered Lands proved a devastating disappointment to TSR and especially to SSI. After costing more than $1 million and eighteen months to make, with the additional opportunity cost of preventing SSI’s internal developers from doing much of anything else over the course of that period, it sold just 45,917 copies. To put this figure into perspective, consider that it’s barely 5000 more copies than the last tired release of the old Gold Box line, or that it’s about one-sixth of the sales of Pool of Radiance — this in spite of an expanded marketplace in which the number of copies which a hit game could hope to sell was actually far greater than it had been five years before.

When SSI and TSR met again early in 1994, after it had become all too clear that Shattered Lands wasn’t to be the next Pool of Radiance, TSR stated matter-of-factly that they no longer wished to remain in the marriage. Some tense negotiation followed, during which TSR did make some concessions to a frantic SSI, who were facing down the apocalyptic prospect of a license due to expire in less than six months while they still had a lot more Dungeons & Dragons product from third-party developers in the pipeline. TSR agreed to extend the exclusive license for six more months, to January 1, 1995, and to allow SSI to continue to release new games under a non-exclusive license until July 1, 1995. After that, though, the marriage was through. TSR emphasized that there would be no further settlement agreements.

Thus SSI’s final string of Dungeons & Dragons releases, of which there would still be a considerable number, would have something of the feel of a lame-duck session of government. DreamForge Intertainment provided two real-time CRPGs set in TSR’s Gothic world of Ravenloft and a third set in the Forgotten Realms; Cyberlore Studios provided a similar game set in the Arabian Nights World of Al-Qadim; Lion Entertainment provided a Doom-influenced hack-and-slasher set nowhere in particular. An overoptimistic SSI had launched into Dark Sun: Wake of the Ravager, a sequel to Shattered Lands, before the commercial verdict on the first game and TSR’s final judgment on the whole partnership that had led to it had come in. They finished that game up too, after a fashion anyway, and released it, still full of bugs, unimplemented features, and placeholder writing. It became their final in-house-developed Dungeons & Dragons title. It made for a slightly pathetic way to bow out, but at this point they just couldn’t be bothered to do better; they were now a long way indeed from those enthusiastic early days of Pool of Radiance. None of these games sold more than a few tens of thousands of copies. But then, no one, least of all SSI, had much expected them to.

The news that TSR and SSI were parting ways reached the magazines almost immediately. The two newly minted divorcees couldn’t resist a bit of veiled sniping in the press. SSI, for instance, told Computer Gaming World that they were “unhappy with the rules and restrictions imposed with the license that limited their creativity,” and said they could be perfectly happy and very successful making original CRPGs instead. TSR, for their part, said they’d learned a lesson about binding themselves too inextricably to others, and thus wouldn’t be entering into any more exclusive arrangements at all. Instead they’d play the field, signing deals with publishers on a title-by-title basis, and might just learn how to make computer games of their own.

Yet behind all these brave words lurked a difficult reality for both companies; it was by no means clear that either or both of them would really be better off apart than they’d been together. As if it hadn’t had problems enough already, tabletop Dungeons & Dragons was now getting pummeled by a new arrival with huge appeal to the same demographic: Magic: The Gathering, a fast-playing, accessible “collectible card game” of fantasy combat psychologically engineered to sell an endless amount of content to gamers looking for that one perfect card which could give them an edge over their chums. Magic decks were soon eating up much of the shelf space in hobby stores that had once gone to Dungeons & Dragons, and pushing it out of their display windows entirely. TSR’s only solution was the same as it had always been: to churn out yet more source books. And so the spiral of diminishing returns continued.

The contrast between TSR and Wizards of the Coast, the upstart makers of Magic, was a telling one. The latter engaged with their customers directly at every opportunity, skillfully goosing the grass-roots excitement around their products to yet further extremes. But TSR, still led by the widely disliked non-gamer Lorraine Williams, seemed out of touch, utterly disinterested in their fans and their opinions. Ryan Dancey, who has done a lot of research into TSR’s history, sums up the company’s attitude in damning fashion:

In all my research into TSR’s business, across all the ledgers, notebooks, computer files, and other sources of data, there was one thing I never found — one gaping hole in the mass of data we had available. No customer profiling information. No feedback. No surveys. No “voice of the customer.” TSR, it seems, knew nothing about the people who kept it alive.

The brainy kids who used to fall into the Dungeons & Dragons rabbit hole around the time they entered junior high were now getting their first Magic decks at that age instead. With the red ink beginning to pile up to a truly alarming extent — even the novels were no longer selling like they used to — TSR looked to be headed for an ugly reckoning.

And yet, if TSR was in dire straits, SSI’s position was if anything even worse. Without Dungeons & Dragons, they had almost literally nothing; the strongest remaining item in their portfolio was the Tony La Russa Baseball franchise developed by Stormfront Studios. But a baseball simulation alone wouldn’t be enough to sustain the company, and the sales picture of their other recent products wasn’t pretty. They were still in desperate need of a savior, but now lacked even the TSR connection to offer to potential buyers. Who in the age of multimedia would want to buy a failing publisher of stats-heavy wargames and traditionalist CRPGs? Joel Billings didn’t know, but he had no choice but to keep looking for someone crazy enough to take the plunge.

(Sources: As with all of my SSI articles, much of this one is drawn from the SSI archive at the Strong Museum of Play. Other sources include the book Designers and Dragons by Shannon Appelcline; Computer Gaming World of September 1993, December 1993, April 1994, and December 1994; Questbusters of October 1993. Online sources include Matt Barton’s video interviews with Joel Billings and David Shelley and Laura Bowen.

The two Dark Sun games are available as digital purchases at GOG.com.)