As regular readers of this blog are doubtless well aware, we stand now at the cusp not only of a new decade but also of a new era in terms of this history’s internal chronology. The fractious 1980s, marked by a bewildering number of viable computing platforms and an accompanying anything-goes creative spirit in the games that were made for them, are becoming the Microsoft-dominated 1990s, with budgets climbing and genres hardening (these last two things are not unrelated to one another). CD-ROM, the most disruptive technology in gaming since the invention of the microprocessor, hasn’t arrived as quickly as many expected it would, but it nevertheless looms there on the horizon as developers and publishers scramble to prepare themselves for the impact it must have. For us virtual time travelers, then, there’s a lot to look forward to. It should be as exciting a time to write about — and hopefully to read about — as it was to live through.

Yet a period of transition like this also tempts a writer to look backward, to think about the era that is passing in terms of what was missed and who was shortchanged. It’s at a time like this that all my vague promises to myself to get to this story or that at some point come home to roost. For if not now, when? In that light, I hope you’ll forgive me for forcing you to take one or two more wistful glances back with me before we stride boldly forward into our future of the past. There’s at least one more aspect of 1980s gaming, you see, that I really do feel I’d be remiss not to cover in much better detail than I have to this point: the astonishing, and largely British, legacy of the open-world action-adventure.

First, a little taxonomy to make sure we’re all on the same page. The games I want to write about take the themes and mechanics of adventure games — meaning text adventures during most of the era in question — and combine them with the graphics and input methods of action games; thus the name of “action-adventure.” Still, neither the name nor the definition conveys what audacious achievements the best of these games could be. On computers which often still had to rely on cassettes rather than disks for storage, which struggled to run even Infocom-level text adventures, almost universally young programmers, generally working alone or in pairs, proposed to create huge virtual worlds to explore — worlds which were to be depicted not in text but visually, running in organic, fluid real time. It was, needless to say, a staggeringly tall order. The programmers who tackled it did so because, being so young, they simply didn’t know any better. What’s remarkable is the extent to which they succeeded in their goals.

Which is not to say that games in this category have aged as well as, say, the majority of the Infocom catalog. Indeed, herein lies much of the reason that I’ve rather neglected these games to date. As all you regulars know by now, I place a premium on fairness and solubility in adventure-game design. I find it hard to recommend or overly praise games which lack this fundamental good faith toward their players, even if they’re wildly innovative or interesting in other ways.

That said, though, we shouldn’t entirely forget the less-playable games of history which pushed the envelope in important ways. And among the very most interesting of such interesting failures are many games of the early action-adventure tradition.

It’s not hard to pinpoint the reasons that these games ended up as they are. Their smoothly-scrolling and/or perspective-bending worlds make them hard to map, and thus hard for the player to methodically explore, in contrast to the grid-based movement of text adventures or early CRPGs. The dynamism of their worlds in contrast to those of those other genres leave them subject to all sorts of potentially game-wrecking emergent situations. Their young creators had no grounding in game design, were in fact usually far more interested in the world they were creating inside their primitive instruments than they were in the game they were asking their players to solve there. And in this era neither developers nor publishers had much of an inkling about the concept of testing. We should perhaps be more surprised that as many games of this stripe ended up as playable as they are than the reverse.

As I’ve admitted before, it’s inevitably anachronistic to return to these ancient artifacts today. In their own day, players were so awe-struck by these worlds’ very existence that they weren’t usually overly fixated on ending all the fun of exploring them with a victory screen. So, I’m going to relax my usual persnicketiness on the subject of fairness just a bit in favor of honoring what these games did manage to achieve. On this trip back through time, at least, let’s try to see what players saw back in the day and not quibble too much over the rest.

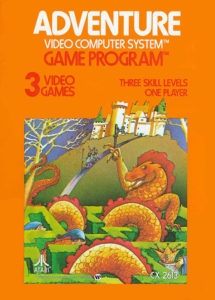

In this first article, we’ll go to the United States to look at the development of the very first action-adventure. It feels appropriate for such a beast to have started life as a literal translation of the original adventure game — Will Crowther and Don Woods’s Adventure — into a form manageable on the Atari VCS game console. The consoles aren’t my primary focus for this history, but this particular console game was just so important for future games on computers that my neglect of it has been bothering me for years.

After this article, we’ll turn the focus to Britain, the land where the challenge laid down by the Atari VCS Adventure was picked up in earnest, to look at some of the more remarkable feats of virtual world-building of the 1980s. And after that, and after looking back at one more subject that’s been sticking in his craw — more on that when the time comes — your humble writer here can start to look forward again from his current perch in the historical timeline with a clearer conscience.

A final note: I am aware that games of this type have a grand tradition of their own in Japan, which arrived on American shores through Nintendo Entertainment System titles like 1986’s The Legend of Zelda. I hope fans of such games will forgive me for neglecting them. My arguments for doing so are the usual suspects: that writing about them really would be starting to roam dangerously far afield from this blog’s core focus on computer gaming, that my own knowledge of them is limited to say the least, and that it’s not hard to find in-depth coverage of them elsewhere.

Adventure (1980)

Like so many others, Warren Robinett had his life changed by Will Crowther and Don Woods’s game of Adventure. In June of 1978, he was 26 years old and was working for Atari as a programmer of games for their VCS console, which was modestly successful at the time but still over a year removed from the massive popularity that would follow. More due to the novelty of the medium and upper management’s disinterest in the process of making games than any spirit of creative idealism, Atari at the time operated on the auteur model of videogame development. Programmers like Robinett were not only expected also to fill the role of designers — a role that had yet to be clearly defined anywhere as distinct from programming — but to function as their own artists and writers. To go along with this complete responsibility, they were given complete control of every aspect of their games, including the opportunity to decide what sorts of games to make in the first place. On Robinett’s first day of work, according to his own account, his new boss Larry Kaplan had told him, “Your job is to design games. Now go design one.” The first fruit of his labor had been a game called Slot Racers, a simple two-player exercise in maze-running and shooting that was very derivative of Combat, the cartridge that was bundled with every Atari VCS sold.

With Slot Racers under his belt, Robinett was expected, naturally, to come up with a new idea for his next game. Luckily, he already knew what he wanted to do. His roommate happened to work at the storied Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab, and one day had invited him to drop by after hours to play a neat game called Adventure on the big time-shared computers that lived there. Robinett declared it to be “the coolest thing I’ve ever seen.” He decided that very night that he wanted to make his next project an adaptation of Adventure for the Atari VCS.

On the face of it, the proposition made little sense. My description of Robinett’s Slot Racers as derivative of Combat begins to sound like less of a condemnation if one considers that no one had ever anticipated the Atari VCS being used to run games that weren’t built, as Combat and Slot Racers had been, from the simple-minded raw material of the earliest days of the video arcades. The machine’s designers had never, in other words, intended it to go much beyond Pong and Breakout. Certainly the likes of Adventure had never crossed their minds.

Adventure consisted only of text, which the VCS wasn’t terribly adept at displaying, and its parser accepted typed commands from a keyboard, which the VCS didn’t possess; the latter’s input mechanism was limited to a joystick with a single fire button. The program code and data for Adventure took more than 100 K of storage space on the big DEC PDP-10 computer on which it ran. The Atari VCS, on the other hand, used cartridge-housed ROM chips capable of storing a program of a maximum of 4 K of code and data, and boasted just 128 bytes — yes, bytes — of memory for the volatile storage of in-game state. In contrast to a machine like the PDP-10 — or for that matter to just about any other extant machine — the VCS was shockingly primitive to program. There not being space enough to store the state of the screen in those 128 bytes, the programmer had to manually control the electron beam which swept left to right and top to bottom sixty times per second behind the television screen, telling it where it should spray its blotches of primary colors. Every other function of a game’s code had to be subsidiary to this one, to be carried out during those instants when the beam was making its way back to the left side of the screen to start a new line, or — the most precious period of all — as it moved from the end of one round of painting at the bottom right of the screen back to the top left to start another.

The creative freedom that normally held sway at Atari notwithstanding, Robinett’s bosses were understandably resistant to what they viewed as his quixotic quest. Undeterred, he worked on it for the first month in secret, hoping to prove to himself as much as anyone that it could be done.

It was appropriate in a way that it should have been Warren Robinett among all the young programmers at Atari who decided to bring to the humble VCS such an icon of 1970s institutional computing — a rarefied environment far removed from the populist videogames, played in bars and living rooms, that were Atari’s bread and butter. Almost all of the programmers around him were self-taught hackers, masters of improvisation whose code would have made any computer-science professor gasp in horror but whose instincts were well-suited to get the most out of the primitive hardware at their disposal. Robinett’s background, however, was very different. He brought with him to Atari a Bachelor’s Degree in computer science from Rice University and a Master’s from the University of California, Berkeley, and along with them a grounding in the structure and theory of programming which his peers lacked. He was, in short, the perfect person at Atari to be having a go at this project. While he would never be one of the leading lights of the programming staff in terms of maximizing the VCS’s audiovisual capabilities, he knew how to design the data structures that would be necessary to make a virtual world come to life in 4 K of ROM and 128 bytes of RAM.

Robinett’s challenge, then, was to translate the conventions of the text adventure into a form that the VCS could manage. This naturally entailed turning Crowther and Woods’s text into graphics — and therein lies an amusing irony. In later years, after they were superseded by various forms of graphic adventures, text adventures would come to be seen by many not so much as a legitimate medium in themselves as a stopgap, an interim way to represent a virtual world on a machine that didn’t have the capability to display proper graphics. Yet Robinett came to this, the very first graphic adventure, from the opposite point of view. What he really wanted to do was to port Crowther and Woods’s Adventure in all its textual glory to the Atari VCS. But, since the VCS couldn’t display all that text, he’d have to find a way to make do with crude old graphics.

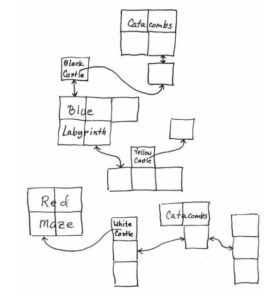

The original Adventure, like all of the text adventures that would follow, built its geography as a topology of discrete “rooms” that the player navigated by typing in compass directions. In his VCS game, Robinett represented each room as a single screen. Instead of typing compass directions, you move from room to room simply by guiding your avatar off the side of a screen using the joystick: north becomes the upper boundary of the screen, east the right-hand boundary, etc. Robinett thus created the first VCS game to have any concept of a geography that spanned beyond what was visible on the screen at any one time. The illustration below shows the text-adventure-like map he crafted for his world.

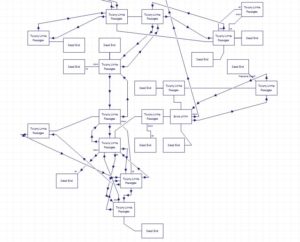

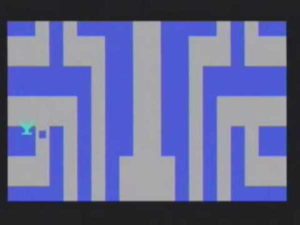

It’s important to note, though, that even such a seemingly literal translation of a text adventure’s geography to a graphical game brought with it implications that may not be immediately obvious. Most notably, your avatar can move about within the rooms of Robinett’s game, a level of granularity that its inspiration lacks; in Crowther and Woods’s Adventure, you can be “in” a “room” like “End of Road” or “Inside Building,” but the simulation of space extends no further. The effect these differences have on the respective experiences can be seen most obviously in the two games’ approaches to mazes. Crowther and Woods’s (in)famous “maze of twisty little passages” is built out of many individual rooms; the challenge comes in charting the one-way interconnections between them all. In Robinett’s game, however, the mazes — there are no less than four of them for the same reason that mazes were so common in early text adventures: they’re cheap and easy to implement — are housed within the rooms, even as they span multiple rooms when taken in their entirety.

It’s important to note, though, that even such a seemingly literal translation of a text adventure’s geography to a graphical game brought with it implications that may not be immediately obvious. Most notably, your avatar can move about within the rooms of Robinett’s game, a level of granularity that its inspiration lacks; in Crowther and Woods’s Adventure, you can be “in” a “room” like “End of Road” or “Inside Building,” but the simulation of space extends no further. The effect these differences have on the respective experiences can be seen most obviously in the two games’ approaches to mazes. Crowther and Woods’s (in)famous “maze of twisty little passages” is built out of many individual rooms; the challenge comes in charting the one-way interconnections between them all. In Robinett’s game, however, the mazes — there are no less than four of them for the same reason that mazes were so common in early text adventures: they’re cheap and easy to implement — are housed within the rooms, even as they span multiple rooms when taken in their entirety.

Crowther and Woods’s maze of twisty little passages, a network of confusing room interconnections where going north and then going south usually won’t take you back to where you started.

Warren Robinett’s graphical take on the adventure-game maze; it must be navigated within the rooms as well as among them. The dot at left is the player’s avatar, which at the moment is carrying the Enchanted Chalice whose recovery is the goal of the game.

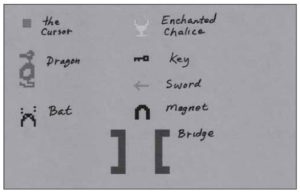

Beyond the challenges of mapping its geography, much of Crowther and Woods’s game revolves around solving a series of set-piece puzzles, usually by using a variety of objects found scattered about within the various rooms; you can pick up such things as keys and lanterns and carry them about in your character’s “inventory” to use elsewhere. Robinett, of course, had to depict such objects graphically. To pick up an object in his game, you need simply bump into it with your avatar; to drop it you push the fire button. Robinett considered trying to implement a graphical inventory screen for his game, but in the end chose to wave any such tricky-to-implement beast away by only allowing your avatar to carry one item at a time. Similarly, the “puzzles” he placed in the game, such as they are, are all simple enough that they can be solved merely by bringing an appropriate object into the vicinity of the problem. Opening a locked gate, for instance, requires only that the player walk up to it toting the appropriate key; ditto attacking a dragon with a sword. By these means, Robinett pared down the “verbs” in his game to the equivalent of the text parser’s movement commands, its “take” and “drop” commands, and a sort of generic, automatically-triggered “use” action that took the place of all the rest of them. (Interestingly, the point-and-click, non-action-oriented graphical adventures that would eventually replace text adventures on the market would go through a similar process of simplification, albeit over a much longer stretch of time, so that by the end of the 1990s most of them too would offer no more verbs than these.)

The text-to-graphics adaptations we’ve seen so far would, with the exception only of the mazes, seem to make of Robinett’s Adventure a compromised shadow of its inspiration, lacking not only its complexity of play but also, thanks to the conversion of Crowther and Woods’s comparatively refined prose to the crudest of graphics, its flavor as well. Yet different mediums do different sorts of interactivity well. Robinett managed, despite the extreme limitations of his hardware, to improve on his inspiration in certain ways, to make some aspects of his game more complicated and engaging in compensation for its simplifications. Other than the mazes, the most notable case is that of the other creatures in the world.

The world of the original Adventure isn’t an entirely uninhabited place — it includes a dwarf and a pirate who move about the map semi-randomly — but these other actors play more the role of transitory annoyances than that of core elements of the game. With the change in medium, Robinett could make his other creatures play a much more central role. Using an approach he remains very proud of to this day, he gave his four creatures — three dragons and a pesky, object-stealing bat, an analogue to Crowther and Woods’s kleptomaniacal pirate — “fears” and “desires” to guide their movements about the world. With the addition of this basic artificial intelligence, his became a truly living world sporting much emergent possibility: the other creatures continue moving autonomously through it, pursuing their own agendas, whether you’re aware of them or not. When you do find yourself in the same room/screen as one of the dragons, you had best run away if you don’t have the sword. If you do, the hunted can become the hunter: you can attempt to kill your stalker. These combat sequences, like all of the game, run in real time, another marked contrast with the more static world of the Crowther and Woods Adventure. Almost in spite of Robinett’s best intentions, the Atari VCS’s ethos of action-based play thus crept into his staid adventure game.

Robinett’s Adventure was becoming a game with a personality of its own rather than a crude re-implementation of a text game in graphics. It was becoming, in other words, a game that maximized the strengths of its medium and minimized its weaknesses. Along the way, it only continued to move further from its source material. Robinett had originally planned so literal a translation of Crowther and Woods’s Adventure that he had sought ways to implement its individual puzzles; he remembers struggling for some time to recreate his inspiration’s “black rod with a rusty star on the end,” which when waved in the right place creates a bridge over an otherwise impassable chasm. In the end, he opted instead to create a movable bridge object which you can pick up and carry around, dropping it on walls to create passages. Robinett:

Direct transliterations from text to video format didn’t work out very well. While the general idea of a videogame with rooms and objects seemed to be a good one, the graphic language of the videogame and the verbal language of the text dialogue turned out to have significantly different strengths. Just as differences between filmed and live performance caused the art form of cinema to slowly diverge from its parent, drama, differences between the medium of animated graphics and the medium of text have caused the animated adventure game to diverge from the text-adventure game.

So, Robinett increasingly turned away from direct translation in favor of thematic analogues to the experience of playing Adventure in text form. To express the text-based game’s obsession with lighted and dark rooms and the lantern that turns the latter into the former, for instance, he included a “catacombs” maze where only the few inches immediately surrounding your avatar can be seen.

But even more radical departures from his inspiration were very nearly forced upon him. When Robinett showed his work-in-progress, heretofore a secret, to his management at Atari, they liked his innovations, but thought they could best be applied to a game based on the upcoming Superman movie, for which Atari had acquired a license. Yet Robinett remained wedded to his plans for a game of fantasy adventure, creating no small tension. Finally another programmer, John Dunn, agreed to adapt the code Robinett had already written to the purpose of the Superman game while Robinett himself continued to work on Adventure. Dunn’s game, nowhere near as complex or ambitious as Robinett’s but nevertheless clearly sporting a shared lineage with it, hit the market well before Adventure, thereby becoming the first released Atari VCS game with a multi-screen geography. Undaunted, Robinett soldiered on to finish creating the new genre of the action-adventure.

The Atari Adventure‘s modest collection of creatures and objects. The “cursor” represents the player’s avatar. Its shape was actually hard-coded into the Atari VCS, where it was intended to represent the ball in a Pong-like game — a telling sign of the only sorts of games the machine’s creators had envisioned being run on it. And if you think the dragons look like ducks, you’re not alone. Robinett never claimed to be an artist…

Ambitious though it was in contrast to Superman, his graphic-based adventure game of 4 K must be inevitably constrained in contrast to a text-based game of more than 100 K. He wound up with a world of about 30 rooms — as opposed to the 130 rooms of his inspiration — housing a slate of seven totable objects: three keys, each opening a different gate; a sword for fighting the dragons; the bridge; a magnet that attracts to it other objects that may be inaccessible directly; and the Enchanted Chalice that you must find and return to the castle where you begin the game in order to complete it. (Rather than the fifteen treasures of Crowther and Woods’s Adventure, Robinett’s game has just this one.)

The constraints of the Atari VCS ironically allowed Robinett to avoid the pitfall that dogs so many later games of this ilk: a tendency to sprawl out into incoherence. Adventure, despite or perhaps because of its primitiveness, is playable and soluble, and can be surprisingly entertaining even today. To compensate for both his constrained world and the youngsters who formed the core of Atari’s customers, Robinett designed the game with three selectable modes of play: a simplified version for beginners and/or the very young, a full version, and a version that scattered all of the objects and creatures randomly about the world to create a new challenge every time. This last mode was obviously best-suited for players who had beaten the game’s other modes, for whom it lent the $25 cartridge a welcome modicum of replayability.

Thanks to the efforts of Jason Scott and archive.org, Adventure can be played today in a browser. Failing that, the video below, prepared by Warren Robinett for his postmortem of the Atari Adventure at the 2015 Game Developers Conference, shows a speed run through the simplified version of the game — enough to demonstrate most of its major elements.

Robinett finished his Adventure in early 1979, about two years after Crowther and Woods’s game had first taken institutional computing by storm and about eight months after he’d begun working on his videogame take on their concept. (True to his role of institutional computing’s ambassador to the arcade, he’d spent most of that time working concurrently on what seemed an even more impossible task: a BASIC programming system for the Atari VCS, combining a cartridge with a pair of hardware controllers that together formed an awkward keyboard.) From the beginning right up to the date of its release, his game’s name remained simply Adventure, nobody apparently ever having given any thought to the confusion this could create among those familiar with Crowther and Woods’s game. Frustrated by Atari’s policy of giving no public credit to the programmers who created their games, one of Robinett’s last additions was a hidden Easter egg, one of videogaming’s first. It took the form of a secret room housing the only text in this game inspired by a text adventure, spelling out the message “Created by Warren Robinett.” Unhappy with his fixed salary of about $22,000 per year, Robinett left Atari shortly thereafter, going on to co-found The Learning Company, a pioneer in educational software. The first title he created there, Rocky’s Boots, built on many of the techniques he’d developed for Adventure, although it ran on an Apple II computer rather than the Atari VCS.

In the wake of Robinett’s departure, Atari’s marketing department remained nonplussed by this unusually complex and cerebral videogame he had foisted on them. Preoccupied by Atari’s big new game for the Christmas of 1979, a port of the arcade sensation Asteroids, they didn’t even release it until June of 1980, more than a year after Robinett had finished it. Yet the late release date proved to be propitious, coming as it did just after the Atari VCS’s first huge Christmas season, when demand for games was exploding and the catalog of available games was still fairly small. Adventure became something of a sleeper hit, selling first by random chance, plucked by nervous parents off of patchily-stocked store shelves, and then by word of mouth as its first players recognized what a unique experience it really was. Robinett claims it wound up selling 1 million copies, giving the vast majority of that million their very first taste of a computer-based adventure game.

For that reason, the game’s importance for our purposes extends far beyond that of being just an interesting case study in converting from one medium to another. A long time ago, when this blog was a much more casual affair than it’s since become, I wrote these words about Crowther and Woods’s Adventure:

It has long and rightfully been canonized as the urtext not just of textual interactive fiction but of a whole swathe of modern mainstream videogames. (For example, trace World of Warcraft‘s lineage back through Ultima Online and Richard Bartle’s original MUD and you arrive at Adventure.)

I’m afraid I rather let something fall by the wayside there. Robinett’s Adventure, the first of countless attempts to apply the revolutionary ideas behind Crowther and Woods’s game to the more mass-market-friendly medium of graphics, is in fact every bit as important to the progression outlined above as is MUD. [1]As for MUD: don’t worry, I have plans to round it up soon as well.

That said, my next couple of articles will be devoted to charting the game’s more immediate legacy: the action-adventures of the 1980s, which would borrow heavily from its conventions and approaches. While the British programmers we’ll be turning to next had at their disposal machines exponentially more powerful than Robinett’s Atari VCS, they expanded their ambitions exponentially to match. Whether considered as technical or imaginative feats, or both, the action-adventures to come would be among the most awe-inspiring virtual worlds of their era. If you grew up with these games, you may be nodding along in agreement right now. If you didn’t, you may be astonished at how far their young programmers reached, and how far some of them managed to grasp despite all the issues that should have stopped them in their tracks. But then, in this respect too they were only building on the tradition of Warren Robinett’s Adventure.

(Sources: the book Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost; Warren Robinett’s chapter “Adventure as a Video Game: Adventure for the Atari 2600″ from The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology; Next Generation of January 1998; Warren Robinett’s Adventure postmortem from the 2015 Game Developers Conference; Robinett’s interview from Halcyon Days. As noted in the article proper, you can play Robinett’s Adventure in your browser at archive.org.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | As for MUD: don’t worry, I have plans to round it up soon as well. |

|---|

Pedro Timóteo

August 11, 2017 at 3:43 pm

Great as always, etc. :) I’ve never actually played the VCS Adventure, although I’ve watched videos of it. I never had a VCS at the time, I had a Videopac (Odyssey2 in the US), which didn’t really have any game like this; the closest thing to its complexity was Quest for the Rings, which included a board game in the box (with the video game being used to resolve encounters), but could also be played as a pure console game (I’d call it a precursor to Gauntlet, in fact).

By “British arcade-adventures”, I assume you mean series like Wally Week, Skool Daze, Magic Knight, Dizzy, and similar games, right? And perhaps others like Jet Set Willy, or isometric games such as Ultimate’s, or Jon Ritman’s? No need to answer if you want to keep it a surprise. :)

Typo: “Robinet finished his Adventure”, missing one “T”.

Jimmy Maher

August 11, 2017 at 6:30 pm

Thanks!

You’re generally on the right track, although only one of the games you mention will get specific coverage in this series. And yeah, I think I’ll keep the titles that I will talk about a surprise. ;)

stepped pyramids

August 11, 2017 at 4:30 pm

Typo: “volitale” => “volatile”

Jimmy Maher

August 11, 2017 at 6:30 pm

Thanks!

Remz

August 11, 2017 at 6:17 pm

Minor geeky correction: The Atari VCS outputs sixty frames per second, not thirty.

Jimmy Maher

August 11, 2017 at 6:33 pm

Thanks! I always get tripped up because I go back to thinking about interlace mode on the Amiga…

Eric Lundquist

August 11, 2017 at 8:32 pm

Man, I played Adventure SO much back then that I am surprised that my kids don’t have the mazes memorized via my DNA. So much fun to get eaten by a dragon then have the Bat pick up the dragon corpse (and you in it) and give you a tour of the whole place.

I tried the online one and won it on game setting 3 in just a few minutes, got lucky on item dispersement.

I’d always hoped you would cover Stuart Smith, either Ali Bab, The Return of Heracles, or Adventure Construction Set.

MalcolmM

August 12, 2017 at 10:02 pm

I would also very much enjoy an article on Stuart Smith. I played and completed all his action/adventure games – great fun, especially two player with two joysticks.

Alex Smith

August 11, 2017 at 9:30 pm

So for the longest time Adventure was dated to 1979 because that’s the year Robinette finished the game, leading him to assume it came out that Christmas. This assumption has turned to “fact” in the modern era, but it appears this date is not correct, as all evidence points to the game actually being released in Spring 1980. The two most important pieces of evidence for this are a registration in the US Copyright database giving the date of publication as June 29th, 1980, and an ad found in the newspaper of Medicine Hat, Alberta, in the May 9, 1980 issue listing Adventure as a new arrival. Lest someone argue it came to Canada much later than the US for some reason, an ad in the June 1, 1980 edition of the Santa Cruz Sentinel also identifies Adventure as a new game. Furthermore, Atari’s 1980 product catalog lists it as “available soon,” while it first appears in a list of games in a Hobbyworld ad in Infoworld in the June issue after not appearing in the same ad in the May issue.

AguyinaRPG

August 12, 2017 at 5:30 am

Well the earliest ads I found mentioning it as a new game were Plain Dealer, April 11, 1980 and Mobile Register May 1st, 1980. Neither appear to show the game, but both are in very low quality print so I can’t say for certain.

Jimmy Maher

August 12, 2017 at 8:27 am

Thanks for this. I questioned the date briefly, but obviously not thoroughly enough — mainly because Robinett’s development timeline is pretty clear, and he’s never alluded to Atari sitting on the finished game for so long before releasing it.

Alex Smith

August 12, 2017 at 2:33 pm

Yeah, the problem is that Robinette not only left Atari, but also the US in late 1979, so he was not actually around to see if it were released or not. I could not tell you why they sat on it, but I imagine Robinette assumed that any game he finished in the middle of the year would be out before the end of it, which is not an unreasonable assumption.

Sniffnoy

August 11, 2017 at 9:46 pm

This is pretty tangential, but on the topic of video games and things easily missed: This one’s not till 1994, and is a console game, but I’m wondering if you have any intent of writing about “Pac-Man 2: The New Adventures” (which is, yes, an adventure game, though a pretty unusual one). It’s more frustrating than fun, and not influential, but that’s kind of precisely why I’m mentioning it: It’s a weird little dead-end in adventure gaming design; I’ve never heard of any other game like it. Probably because anyone who actually played “Pac-Man 2” quickly realized it wasn’t something they wanted to copy! But certainly interesting…

Jimmy Maher

August 12, 2017 at 8:29 am

Never heard of it, so no, it wasn’t in my plans. ;) I can take a look, but will see that it would have to a *very* interesting failure to convince me to give it time. The schedule is pretty packed for that year.

Sniffnoy

August 14, 2017 at 7:45 am

That’s basically what I expected! I’m a bit doubtful that it meets that high bar, but let me say a bit about it here anyways. :)

A number of adventure games already draw a bit of a separation between the player and their character. (E.g., you tell your character to do something and they reply that that wouldn’t be a good idea.) Pac-Man 2 (terrible name, but we’re stuck with it) says, what if the player really wasn’t the character? Pac-Man moves about the adventure world on his own and you have only limited ability to direct him. There are two things you can do (note, I’m going to use the button names from the Genesis version): You can use the C button to give the “Look, look” command, possibly coupled with a direction to look in, and hope that Pac-Man notices what you’re trying to point out (if he even listens); or you can use the B button to fire your slingshot at something in the world, as a way of interacting with the world directly. (This is often a useful way of pointing something to Pac-Man when the C button doesn’t suffice. You can also shoot Pac-Man directly if you want to piss him off…) (There’s also the A button, but it’s not relevant for my purposes here. I’m also ignoring the game’s few action sequences for obvious reasons, although they do also nominally stick to basically the same control scheme even as they effectively give you more direct control.)

The thing is that Pac-Man himself is a moody creature… I remember reading something a while back, probably linked from here, asking, why don’t NPCs in adventure games have, like, a finite-state machine of emotions or something? That’s basically what Pac-Man has. Except due to your limited ability to interact with the world, managing it is a total pain in the ass. Most of the time you want to keep him happy, since then he’s more likely to pay attention, though occasionally you might want to, say, deliberately anger him so he’ll kick some important thing, etc. As I said above deliberately angering him is easy (well, most of the time… if he’s sad shooting him will just make him sadder). But keeping him happy isn’t something you can do directly; you’ll have to find things in the world to do that. Which might require going out of your way to find. And once again… you don’t directly control Pac-Man’s motion!

Basically there’s a pretty neat idea underlying the game, that I haven’t seen replicated elsewhere… probably because it’s not actually a very good idea. When you actually play the game it’s less “It’s pretty neat that I don’t control Pac-Man directly” and more “Goddammit Pac-Man! Fricking look!” I’m not sure how you’d make a game that wasn’t frustrating with the control scheme described above; so the whole thing comes off as less “They designed the game around a neat idea” and more “They designed the game around a frustrating control scheme”. (And there’s plenty of extra little frustrations in there too…) Still, from a distance, I have to admit that even if it was a bad idea, it’s still a pretty interesting one!

Jimmy Maher

August 14, 2017 at 8:44 am

That’s sounds… incredibly frustrating. But for some reason I find the idea of a moody Pac-Man hilarious. I’m picturing him in the James Mason role in a videogame remake of A Star is Born, slagging off Mario and Sonic and all these other, younger videogame icons coming up behind him. Happy Pac-Man, sad Pac-Man, angry Pac-Man… one can only hope there isn’t a horny Pac-Man.

Sniffnoy

August 15, 2017 at 1:54 am

Fortunately, there’s not, at least not that I recall…

Gnoman

August 15, 2017 at 4:05 am

There’s no horny Pac-Man in the game, but there is a drunk Pac-Man.

Sniffnoy

August 18, 2017 at 10:53 pm

Huh, I did not remember that. I played it on the Genesis, but I know there was also a SNES version; I wonder how they got that past the Nintendo of America censors?

Pedro Timóteo

August 15, 2017 at 12:26 pm

Besides more recent games such as The Last Guardian and (a bit less recently) Black and White, that description really reminds me of Automata’s Pimania (a very very weird 1982 text adventure, a big part of which was managing the Pi-Man’s moods).

Sniffnoy

August 18, 2017 at 8:32 pm

Huh, interesting! Pimania had come up here before but that aspect hadn’t been mentioned. I might have to go look that up some more…

Sniffnoy

August 19, 2017 at 5:54 am

Also it seems “Hey You, Pikachu!” is also a somewhat related game.

matt w

August 19, 2017 at 12:06 pm

“what if the player really wasn’t the character?”

This reminds me of the Samorost series, which took this approach. There’s a character but most of the things you do involve manipulating the world in ways that are obviously out of the character’s reach, until he progresses. Also everything is so surreal that you pretty explicitly have to click on everything until it works, in many cases the effects of your clicks aren’t exactly predictable. I’ve never tried Samorost 3 because this seems really badly suited to a huge game. (The first large game by this studio, Machinarium, didn’t use this environmental clicking approach.)

Brian Mathews

August 11, 2017 at 9:58 pm

We played Adventure for hours on our trusty old Atari 2600! I remember the day we heard you could find a special dot that let you cross the lines of the connecting corridors and see a secret message… we spent several hours finding it and figuring out how it worked. Little did I realize or understand the history behind this very early Easter Egg.

Of course, now have Ready Player One coming out, which takes the Easter Egg to its full potential!

Martin

August 12, 2017 at 12:39 am

Maybe off track here but now that such a thing is possible, has anyone tried to re-create the Crowther & Woods dungeon as a 1st person perspective experience? That is, use a Quake-like engine and build the original Adventure in it. Why? Well why not. Actually a 1st person version of the VCS Adventure would be interesting too.

Jimmy Maher

August 12, 2017 at 8:38 am

The closest thing I’m aware of along those lines is an adaptation of Vespers (http://ifdb.tads.org/viewgame?id=6dj2vguyiagrhvc2), the game which won the IF Comp in 2005, into a 3D engine: http://orangeriverstudio.com/vespers/. That project, which is helmed by Michael Rubin, got quite a long way, but appears to have stalled in 2014. There should be playable demos around.

In general, though, text and 3D graphics are very different mediums. The mazes and puzzles of Adventure are all pretty dependent on the specific affordances of the parser-driven, textual medium. I suspect that any project that started as an adaptation would end up departing so far from the source material as to be almost unrecognizable — much as happened with Warren Robinett’s adaptation.

Rowan Lipkovits

August 14, 2017 at 3:35 am

Frustratingly, last week I saw a post about a VR version of Crowther & Woods’ Adventure for some new platform such as the Oculus Rift, and can I find a crumb about it now? Of course not!

MrEntropy

August 17, 2017 at 12:58 pm

I’d love to see such a thing. I’d also like to see at least one Zork game be re-imagined in VR.

Keith Palmer

August 12, 2017 at 12:53 am

The recent revival of “as amazing it was anything could be done on the Atari VCS at all, it’s that much more amazing what was accomplished” is, I have to admit, something I look at with a bit of detachment, as my family managed to keep away from “video game systems” altogether, getting into “home computing” instead starting with a TRS-80 Model I. Hearing Warren Robinett went on to “Rocky’s Boots,” though, did very much get my attention, as we had the Radio Shack Color Computer port of that and its successor “Robot Odyssey,” which had its own distinct echoes of “VCS Adventure” now that I think about it. I suppose it’s too much to ask for that this narrative cycle back through Robot Odyssey as well, of course; I’ll be interested in seeing just what the British developments were.

Rowan Lipkovits

August 14, 2017 at 3:45 am

Robinett’s suite of Adventure derivations for the Learning Company — Rocky’s Boots, Robot Odyssey, Gertrude’s Secrets, Gertrude’s Puzzles — could be grist for a satisfying follow-up article on their own… but as they represent a somewhat dead-end school of game design, probably the time will be better spent telling other stories 8)

matt w

August 12, 2017 at 3:08 am

I loved Adventure. Might have been one of the early cult adopters–I’m pretty sure we didn’t hear how great it was from anyone else, but got it just because it looked so much cooler than all the other games. Not that there was anything wrong with shoot-em-ups, but this seemed like something special… and, to our good fortune, it was. I don’t remember how we learned about the easter egg exactly, whether by word of mouth or in a gaming magazine.

One other thing about difficulty–if you flip the difficulty switches it changes the dragon’s AI. One just makes them bite faster, but one makes them run away from the sword instead of impaling themselves on it, which made the game much more challenging–at least for my ten-year-old self.

RavenWorks

August 12, 2017 at 4:00 am

It was recently discovered that Adventure’s easter egg is not actually the first after all: https://edfries.wordpress.com/2017/03/22/chasing-the-first-arcade-easter-egg/

Jimmy Maher

August 12, 2017 at 8:42 am

Okay, “videogaming’s first” is now “one of videogaming’s first.” ;) Thanks!

Alex Smith

August 12, 2017 at 2:38 pm

Tangent maybe not worth mentioning in the article itself, but while Adventure was beaten by even more obscure hidden programmer messages, it is Adventure that gives us the term itself. When the secret room was discovered, Atari software director Steven Wright gave an interview to Electronic Games promising to “plant little Easter Eggs like that” in more games.

Josh Lawrence

August 12, 2017 at 4:57 pm

Adventure was one of my all-time favorite Atari 2600 games when growing up. As you mention, its multi-screen geography and the fact that the antagonists roam about independently within that geography gave it a living world feel miles away from anything on the Atari VCS other than its pale cousin Superman, and made it fascinating (the paths through those mazes are still hard-wired muscle-memory whenever I pick it up again).

A fun emergent aspect related to when you get eaten by a dragon, stuck in its belly as the dragon sits motionless in satiated triumph: usually this is the occasion to hit the reset switch, but if you wait long enough the bat will come by and pick up the dragon with you still in the dragon’s stomach, giving you a dizzying tour of the game world as the bat experiences it, rapidly flying from screen to screen until the bat finds an item it wants to trade the dragon for.

But not only can the bat pick you up indirectly, but you can pick up the bat while its holding something, which opened up a ‘construct your own Adventure scenario’ opportunity for me and my brother-in-law, who also loved the game. We relied on the fact that if you carried the bat into the opened yellow castle, and released him in one of several positions, his flight would loop, trapping him in that yellow castle room (I wonder if this was ability to trap the bat is a bug, or something Robinette intended as a way to keep the bat controlled as he tested other aspects of the game). Usually we’d trap the jerk while he was holding the yellow key. With the bat trapped, one could move objects around freely without the bat being able to disturb them.

So I and my brother-in-law would each take turns doing this: unlock all the castles, kill all the dragons, trap the bat, and *then*, with the other person out of the room, place objects where we wished (for instance, making a ‘puzzle’ by placing a needed object in the black castle, re-locking the castle gate, and then pushing the black key deep in the side of the black castle and dropping it there, making it invisible and only retrievable by use of the magnet). When a ‘scenario’ was sufficiently set-up, hit the reset switch, which revives all the dragons but keeps the objects where one has placed them, and then the other person would re-enter the room and play your scenario. Great memories of this unintended ‘custom’ fun that Adventure afforded, something impossible with any other VCS game.

Jimmy Maher

August 14, 2017 at 9:41 am

This is an amazing story. Thanks!

Doug Orleans

August 13, 2017 at 6:10 am

I’m not familiar with the British games you allude to, so I’m looking forward to that article. But I always felt that this was the successor to 2600 Adventure: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galahad_and_the_Holy_Grail

Rowan Lipkovits

August 14, 2017 at 3:41 am

I never knew about Superman using Adventure’s source code, though in retrospect it makes a lot of sense. The 2600’s Haunted House also stood on the shoulders of Robinett, which could warrant a mention.

Lee Jones

September 1, 2017 at 12:21 am

Yes, Haunted House is another good example of a seemingly simplistic game that has an actual plot, as well.

David Boddie

August 15, 2017 at 1:07 pm

Assuming we’re talking about the same kind of games, another description of them that’s often used is “arcade adventure”, having arcade/action elements within an experience that involves exploration, puzzle and adventure elements.

Wikipedia redirects “Arcade adventure” to “Action-adventure” which is unfortunate because I expect many people used the former to describe these games in Britain rather than the latter.

CdrJameson

August 18, 2017 at 9:00 pm

“Arcade Adventure” is definitely the British term, Pedro Timóteo used it back in the first comment too. Not sure where ‘Action-adventure’ comes from? Presumably it’s the US equivalent.

Brian Bagnall

August 20, 2017 at 5:05 pm

Warren Robinett seems similar to Ron Gilbert in that he has a unique vision and implements his vision with purity. Rocky’s Boots is actually very interesting in all that it is able to accomplish with an “Adventure” type of game engine, especially with states changing while off screen.

Out of curiosity, have you ever considered covering games that were designed but never released? There’s some old Lucasfilm docs kicking around of things like “Lobots” by Ron Gilbert. Frank Gasking’s Games that Weren’t has over 2000 entries. Lots of adventures. Some, like The Adventures of Scooby Doo, are interesting failures.

Corrections:

“up an object up”

“the The”

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2017 at 11:02 am

I actually started on an article like that a few months ago, based on information on unreleased Interplay games that I found in the archive at the Strong. But I ended up abandoning it. It was starting to feel a little too esoteric for its own good, and I confess that’s still the way the idea strikes me.

Thanks for the corrections!

Rodrigo Garcia Carmona

August 20, 2017 at 5:45 pm

An excellent article (as always) but, if I might, I want to make a comment about it.

Actually, Japan has a huge tradition in computer (not console) RPGs with, in fact, a lot of action RPGS, not limiting themselves to copy the Wizardry or Ultima formula. The first of these is Dragon Slayer from Nihon Falcom (an incredibly long-lived company that lasts to this day) released in 1984. This game in particular spanned a huge family of semi-related games. So, the Japan angle is actually hugely related to your work in this blog.

With that said, I understand why you won’t devote much time or space to it. Without knowledge of Japanese it’s extremely difficult to find good information on this “mirror world” (to use your own words) of Japanese narrative-heavy (so to say) or RPG games. In fact, there were also a lot of text adventure games in the early days of japanese computers, and the visual novel genre, which grows in popularity in the west every day, descends from these early examples. So, in a way, we could say that Japan never stopped releasing text adventure games.

Again, is difficult to find out about any of this if you don’t have a grasp of the Japanese language, not only because it’s the language these games used for their gameplay (curiously, Dragon Slayer is completely in English and has very little text), but also because the computer platforms in Japan evolved, until the release of Windows 95, using different standards than the ones we used in the western world.

I won’t ramble any more about this topic (which I find incredibly interesting but probably your readers won’t) and I don’t want you to think that your blog is lacking, because that’s not what I wanted to say. ;)

If I piqued your interest, you can play Dragon Slayer legally using a japanese retro game platform call EGG: https://www.amusement-center.com/project/egg/

Also, if you want to learn about this amazing world, you could do worse than starting with HG101 writeup of the Dragon Slayer family:

http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/dragonslayer/dragonslayer.htm

Or their article about japanese computer platforms:

http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/JPNcomputers/Japanesecomputers.htm

Slightly related to this, as a Spaniard I want to point you to “La Abadía del Crimen”, an amazing game product of the very active spanish game developer community during the 80s, what we call the “golden age of spanish game software”, but probably not known at all outside my country:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Abad%C3%ADa_del_Crimen

Again, sorry for the long comment. You truly do an amazing work and I have been reading this blog for years. Keep up with it!

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2017 at 10:56 am

Thanks for this! I’m well aware that this is a blind spot on the blog, but you’ve identified most of the reasons why. In addition, I’ll confess that I’ve just never felt myself to be on the same wavelength as Japanese pop culture, making it a little hard for me to work up much passion for these topics. So, I’m afraid I’ll be leaving those stories for others to tell. I certainly have enough to keep me busy as it is. ;)

Rodrigo Garcia Carmona

August 21, 2017 at 12:50 pm

Thanks for your response!

Ola

August 26, 2017 at 11:36 pm

I don’t know, but I get the impression that the reputation of La Abadía del Crimen has been growing outside Spain. Tristan Donovan writes about it in Replay (excellent book) and the beautiful remake last year must have caught some attention. I’m Swedish but have known about the game for about 15 years though I didn’t play until I the remake was made available. Enjoyed it very much though its strict adherence to the plot of Eco’s book (and the film) made the twists and turns less interesting. OTH I might have been totally lost if I hadn’t read the book!

Still, the game strikes me as a very peculiar, almost mysteriously impressive design and programming achievement for its era.

Michael Davis

August 20, 2017 at 9:16 pm

“Robinett left Atari before shortly thereafter”

Jimmy Maher

August 21, 2017 at 10:48 am

Thanks!

Howard Lewis Ship

August 25, 2017 at 6:36 pm

Just pointing out this incredible visualization of Adventure’s ROM.

http://benfry.com/distellamap/150dpi/advnture-illus-150dpi.png

Anders Hansson

August 26, 2017 at 10:22 pm

My first arcade adventure was Pharaoh’s Tomb. A British, 1982 game for 16K VIC-20.

It’s clearly inspired by Atari 2600 Adventure but moves at snail pace.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YH-DMRmwTI0

http://www.mobygames.com/game/pharaohs-tomb_

Lee Jones

September 1, 2017 at 12:18 am

I am so pleased to see you give the Atari Adventure its due.

I’m a fan of the 2600, and Adventure is one of my favorites.

I think another good aspect not touched on too often is that the game had a plot. Simplistic as it may be, for the 2600, it’s still a major achievement of Warren that he could craft an actual little story in the constraints of just 128 bytes.

Superman may have come out first, but Adventure rightly deserves the recognition for being the first game with a plot programmed for the Atari 2600.

Wolfeye M.

October 9, 2019 at 3:06 am

I had a version of Adventure for my Apple 2e. I’m holding the disc right now, it’s a “Golden Oldies” collection from a company called Software Country, copyright 1985. No mention of Atari, at least not on the disc’s label, so I’m wondering how that happened. It’s got Adventure, Eliza, Life and Pong on it.

I remember playing Adventure the most.

But, I’m not sure if it’s Robinett’s game, because it has a stick figure as the player character, not just a dot. I remember it otherwise looking and playing like how you describe in your article, so maybe it’s a later port. I’m just wondering if it’s an official one, since the label makes no mention of Atari. What do you think?

I had a lot of fun playing it, wish I could still, but I haven’t had my 2e for a long time. Can’t help but wonder if the disc still works.

I read somewhere else that Atari didn’t give people credit for their games, because they didn’t want other companies poaching their talent. Funny how that led to one of the first Easter Eggs, just because Robbinet wanted credit for his work.

Jimmy Maher

October 9, 2019 at 3:34 pm

The official Atari adventure was only released for the VCS. But it wouldn’t surprise me if someone made a clone for the Apple II. There was a lot of that sort of thing going on at the time.