While wide-area computer networking, packet switching, and the Internet were coming of age, all of the individual computers on the wire were becoming exponentially faster, exponentially more capacious internally, and exponentially smaller externally. The pace of their evolution was unprecedented in the history of technology; had automobiles been improved at a similar rate, the Ford Model T would have gone supersonic within ten years of its introduction. We should take a moment now to find out why and how such a torrid pace was maintained.

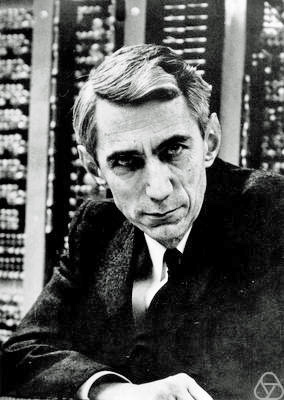

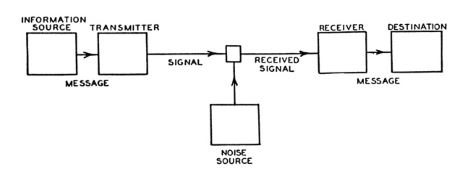

As Claude Shannon and others realized before World War II, a digital computer in the abstract is an elaborate exercise in boolean logic, a dynamic matrix of on-off switches — or, if you like, of ones and zeroes. The more of these switches a computer has, the more it can be and do. The first Turing-complete digital computers, such as ENIAC and Whirlwind, implemented their logical switches using vacuum tubes, a venerable technology inherited from telephony. Each vacuum tube was about as big as an incandescent light bulb, consumed a similar amount of power, and tended to burn out almost as frequently. These factors made the computers which employed vacuum tubes massive edifices that required as much power as the typical city block, even as they struggled to maintain an uptime of more than 50 percent — and all for the tiniest sliver of one percent of the overall throughput of the smartphones we carry in our pockets today. Computers of this generation were so huge, expensive, and maintenance-heavy in relation to what they could actually be used to accomplish that they were largely limited to government-funded research institutions and military applications.

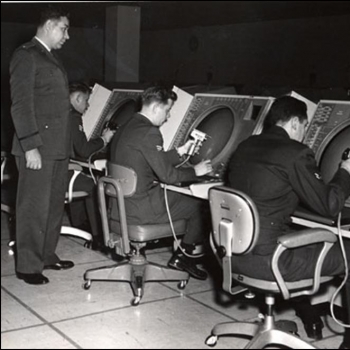

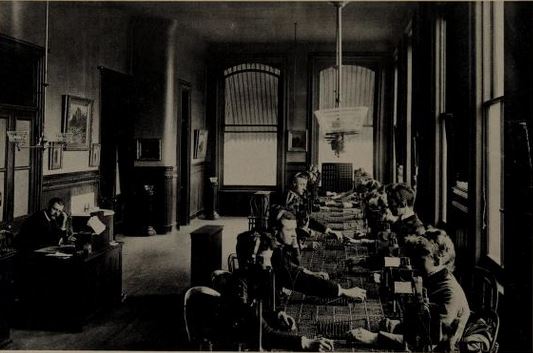

Computing’s first dramatic leap forward in terms of its basic technological underpinnings also came courtesy of telephony. More specifically, it came in the form of the transistor, a technology which had been invented at Bell Labs in December of 1947 with the aim of improving telephone switching circuits. A transistor could function as a logical switch just as a vacuum tube could, but it was a minute fraction of the size, consumed vastly less power, and was infinitely more reliable. The computers which IBM built for the SAGE project during the 1950s straddled this technological divide, employing a mixture of vacuum tubes and transistors. But by 1960, the computer industry had fully and permanently embraced the transistor. While still huge and unwieldy by modern standards, computers of this era were practical and cost-effective for a much broader range of applications than their predecessors had been; corporate computing started in earnest in the transistor era.

Nevertheless, wiring together tens of thousands of discrete transistors remained a daunting task for manufacturers, and the most high-powered computers still tended to fill large rooms if not entire building floors. Thankfully, a better way was in the offing. Already in 1958, a Texas Instruments engineer named Jack Kilby had come up with the idea of the integrated circuit: a collection of miniaturized transistors and other electrical components embedded in a silicon wafer, the whole being suitable for stamping out quickly in great quantities by automated machinery. Kilby invented, in other words, the soon-to-be ubiquitous computer chip, which could be wired together with its mates to produce computers that were not only smaller but easier and cheaper to manufacture than those that had come before. By the mid-1960s, the industry was already in the midst of the transition from discrete transistors to integrated circuits, producing some machines that were no larger than a refrigerator; among these was the Honeywell 516, the computer which was turned into the world’s first network router.

As chip-fabrication systems improved, designers were able to miniaturize the circuitry on the wafers more and more, allowing ever more computing horsepower to be packed into a given amount of physical space. An engineer named Gordon Moore proposed the principle that has become known as Moore’s Law: he calculated that the number of transistors which can be stamped into a chip of a given size doubles every second year.[1]When he first stated his law in 1965, Moore actually proposed a doubling every single year, but revised his calculations in 1975. In July of 1968, Moore and a colleague named Robert Noyce formed the chip maker known as Intel to make the most of Moore’s Law. The company has remained on the cutting edge of chip fabrication to this day.

The next step was perhaps inevitable, but it nevertheless occurred almost by accident. In 1971, an Intel engineer named Federico Faggin put all of the circuits making up a computer’s arithmetic, logic, and control units — the central “brain” of a computer — onto a single chip. And so the microprocessor was born. No one involved with the project at the time anticipated that the Intel 4004 central-processing unit would open the door to a new generation of general-purpose “microcomputers” that were small enough to sit on desktops and cheap enough to be purchased by ordinary households. Faggin and his colleagues rather saw the 4004 as a fairly modest, incremental advancement of the state of the art, which would be deployed strictly to assist bigger computers by serving as the brains of disk controllers and other single-purpose peripherals. Before we rush to judge them too harshly for their lack of vision, we should remember that they are far from the only inventors in history who have failed to grasp the real importance of their creations.

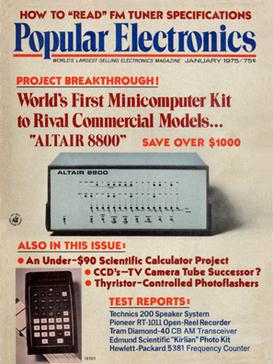

At any rate, it was left to independent tinkerers who had been dreaming of owning a computer of their own for years, and who now saw in the microprocessor the opportunity to do just that, to invent the personal computer as we know it. The January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics sports one of the most famous magazine covers in the history of American technology: it announces the $439 Altair 8800, from a tiny Albuquerque, New Mexico-based company known as MITS. The Altair was nothing less than a complete put-it-together-yourself microcomputer kit, built around the Intel 8080 microprocessor, a successor model to the 4004.

The next milestone came in 1977, when three separate companies announced three separate pre-assembled, plug-em-in-and-go personal computers: the Apple II, the Radio Shack TRS-80, and the Commodore PET. In terms of raw computing power, these machines were a joke compared to the latest institutional hardware. Nonetheless, they were real, Turing-complete computers that many people could afford to buy and proceed to tinker with to their heart’s content right in their own homes. They truly were personal computers: their buyers didn’t have to share them with anyone. It is difficult to fully express today just how extraordinary an idea this was in 1977.

This very website’s early years were dedicated to exploring some of the many things such people got up to with their new dream machines, so I won’t belabor the subject here. Suffice to say that those first personal computers were, although of limited practical utility, endlessly fascinating engines of creativity and discovery for those willing and able to engage with them on their own terms. People wrote programs on them, drew pictures and composed music, and of course played games, just as their counterparts on the bigger machines had been doing for quite some time. And then, too, some of them went online.

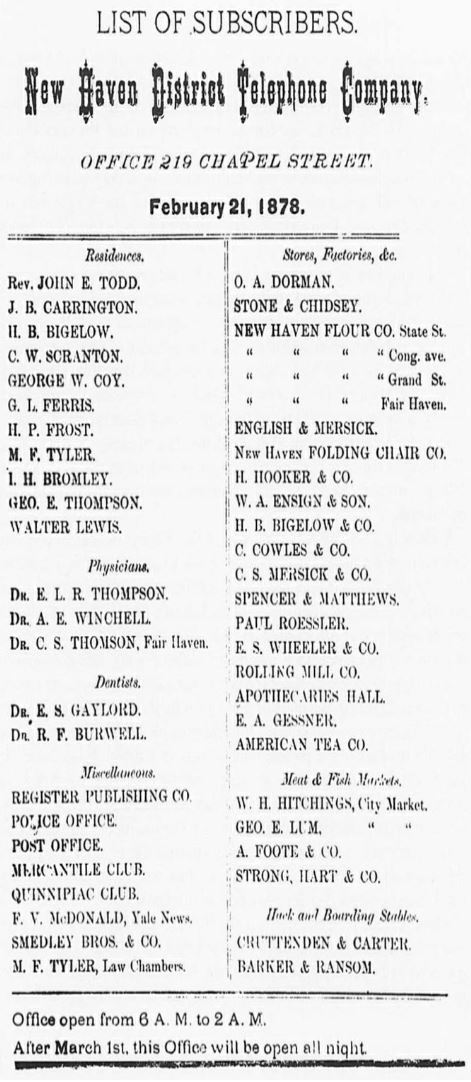

The first microcomputer modems hit the market the same year as the trinity of 1977. They operated on the same principles as the modems developed for the SAGE project a quarter-century before — albeit even more slowly. Hobbyists could thus begin experimenting with connecting their otherwise discrete microcomputers together, at least for the duration of a phone call.

But some entrepreneurs had grander ambitions. In July of 1979, not one but two subscription-based online services, known as CompuServe and The Source, were announced almost simultaneously. Soon anyone with a computer, a modem, and the requisite disposable income could dial them up to socialize with others, entertain themselves, and access a growing range of useful information.

Again, I’ve written about this subject in some detail before, so I won’t do so at length here. I do want to point out, however, that many of J.C.R. Licklider’s fondest predictions for the computer networks of the future first became a reality on the dozen or so of these commercial online services that managed to attract significant numbers of subscribers over the years. It was here, even more so than on the early Internet proper, that his prognostications about communities based on mutual interest rather than geographical proximity proved their prescience. Online chatting, online dating, online gaming, online travel reservations, and online shopping first took hold here, first became a fact of life for people sitting in their living rooms. People who seldom or never met one another face to face or even heard one another’s voices formed relationships that felt as real and as present in their day-to-day lives as any others — a new phenomenon in the history of social interaction. At their peak circa 1995, the commercial online services had more than 6.5 million subscribers in all.

Yet these services failed to live up to the entirety of Licklider’s old dream of an Intergalactic Computer Network. They were communities, yes, but not quite networks in the sense of the Internet. Each of them lived on a single big mainframe, or at most a cluster of them, in a single data center, which you dialed into using your microcomputer. Once online, you could interact in real time with the hundreds or thousands of others who might have dialed in at the same time, but you couldn’t go outside the walled garden of the service to which you’d chosen to subscribe. That is to say, if you’d chosen to sign up with CompuServe, you couldn’t talk to someone who had chosen The Source. And whereas the Internet was anarchic by design, the commercial online services were steered by the iron hands of the companies who had set them up. Although individual subscribers could and often did contribute content and in some ways set the tone of the services they used, they did so always at the sufferance of their corporate overlords.

Through much of the fifteen years or so that the commercial services reigned supreme, many or most microcomputer owners failed to even realize that an alternative called the Internet existed. Which is not to say that the Internet was without its own form of social life. Its more casual side centered on an online institution known as Usenet, which had arrived on the scene in late 1979, almost simultaneously with the first commercial services.

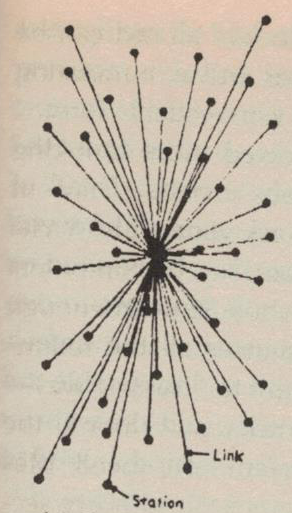

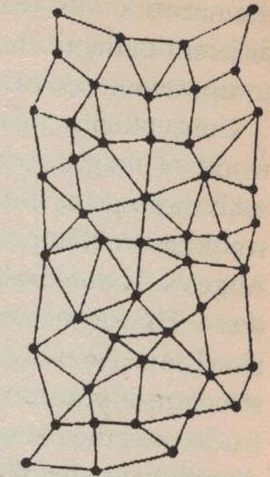

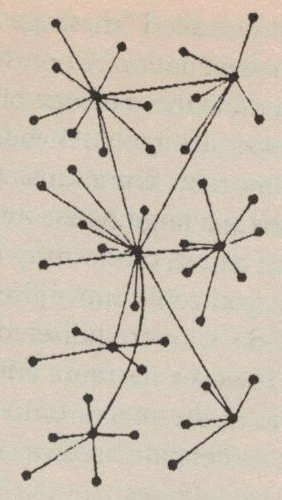

At bottom, Usenet was (and is) a set of protocols for sharing public messages, just as email served that purpose for private ones. What set it apart from the bustling public forums on services like CompuServe was its determinedly non-centralized nature. Usenet as a whole was a network of many servers, each storing a local copy of its many “newsgroups,” or forums for discussions on particular topics. Users could read and post messages using any of the servers, either by sitting in front of the server’s own keyboard and monitor or, more commonly, through some form of remote connection. When a user posted a new message to a server, it sent it on to several other servers, which were then expected to send it further, until the message had propagated through the whole network of Usenet servers. The system’s asynchronous nature could distort conversations; messages reached different servers at different times, which meant you could all too easily find yourself replying to a post that had already been retracted, or making a point someone else had already made before you. But on the other hand, Usenet was almost impossible to break completely — just like the Internet itself.

Strictly speaking, Usenet did not depend on the Internet for its existence. As far as it was concerned, its servers could pass messages among themselves in whatever way they found most convenient. In its first few years, this sometimes meant that they dialed one another up directly over ordinary phone lines and talked via modem. As it matured into a mainstay of hacker culture, however, Usenet gradually became almost inseparable from the Internet itself in the minds of most of its users.

From the three servers that marked its inauguration in 1979, Usenet expanded to 11,000 by 1988. The discussions that took place there didn’t quite encompass the whole of the human experience equally; the demographics of the hacker user base meant that computer programming tended to get more play than knitting, Pink Floyd more play than Madonna, and science-fiction novels more play than romances. Still, the newsgroups were nothing if not energetic and free-wheeling. For better or for worse, they regularly went places the commercial online services didn’t dare allow. For example, Usenet became one of the original bastions of online pornography, first in the form of fevered textual fantasies, then in the somehow even more quaint form of “ASCII art,” and finally, once enough computers had the graphics capabilities to make it worthwhile, as actual digitized photographs. In light of this, some folks expressed relief that it was downright difficult to get access to Usenet and the rest of the Internet if one didn’t teach or attend classes at a university, or work at a tech company or government agency.

The perception of the Internet as a lawless jungle, more exciting but also more dangerous than the neatly trimmed gardens of the commercial online services, was cemented by the Morris Worm, which was featured on the front page of the New York Times for four straight days in December of 1988. Created by a 23-year-old Cornell University graduate student named Robert Tappan Morris, it served as many people’s ironic first notice that a network called the Internet existed at all. The exploit, which its creator later insisted had been meant only as a harmless prank, spread by attaching itself to some of the core networking applications used by Unix, a powerful and flexible operating system that was by far the most popular among Internet-connected computers at the time. The Morris Worm came as close as anything ever has to bringing the entire Internet down when its exponential rate of growth effectively turned it into a network-wide denial-of-service attack — again, accidentally, if its creator is to be believed. (Morris himself came very close to a prison sentence, but escaped with three years of probation, a $10,000 fine, and 400 hours of community service, after which he went on to a lucrative career in the tech sector at the height of the dot-com boom.)

Attitudes toward the Internet in the less rarefied wings of the computing press had barely begun to change even by the beginning of the 1990s. An article from the issue of InfoWorld dated February 4, 1991, encapsulates the contemporary perceptions among everyday personal-computer owners of this “vast collection of networks” which is “a mystery even to people who call it home.”

It is a highway of ideas, a collective brain for the nation’s scientists, and perhaps the world’s most important computer bulletin board. Connecting all the great research institutions, a large network known collectively as the Internet is where scientists, researchers, and thousands of ordinary computer users get their daily fix of news and gossip.

But it is the same network whose traffic is occasionally dominated by X-rated graphics files, UFO sighting reports, and other “recreational” topics. It is the network where renegade “worm” programs and hackers occasionally make the news.

As with all communities, this electronic village has both high- and low-brow neighborhoods, and residents of one sometimes live in the other.

What most people call the Internet is really a jumble of networks rooted in academic and research institutions. Together these networks connect over 40 countries, providing electronic mail, file transfer, remote login, software archives, and news to users on 2000 networks.

Think of a place where serious science comes from, whether it’s MIT, the national laboratories, a university, or [a] private enterprise, [and] chances are you’ll find an Internet address. Add [together] all the major sites, and you have the seeds of what detractors sometimes call “Anarchy Net.”

Many people find the Internet to be shrouded in a cloud of mystery, perhaps even intrigue.

With addresses composed of what look like contractions surrounded by ‘!’s, ‘@’s, and ‘.’s, even Internet electronic mail seems to be from another world. Never mind that these “bangs,” “at signs,” and “dots” create an addressing system valid worldwide; simply getting an Internet address can be difficult if you don’t know whom to ask. Unlike CompuServe or one of the other email services, there isn’t a single point of contact. There are as many ways to get “on” the Internet as there are nodes.

At the same time, this complexity serves to keep “outsiders” off the network, effectively limiting access to the world’s technological elite.

The author of this article would doubtless have been shocked to learn that within just four or five years this confusing, seemingly willfully off-putting network of scientists and computer nerds would become the hottest buzzword in media, and that absolutely everybody, from your grandmother to your kids’ grade-school teacher, would be rushing to get onto this Internet thing before they were left behind, even as stalwart rocks of the online ecosystem of 1991 like CompuServe would already be well on their way to becoming relics of a bygone age.

The Internet had begun in the United States, and the locus of the early mainstream excitement over it would soon return there. In between, though, the stroke of inventive genius that would lead to said excitement would happen in the Old World confines of Switzerland.

In many respects, he looks like an Englishman from central casting — quiet, courteous, reserved. Ask him about his family life and you hit a polite but exceedingly blank wall. Ask him about the Web, however, and he is suddenly transformed into an Italian — words tumble out nineteen to the dozen and he gesticulates like mad. There’s a deep, deep passion here. And why not? It is, after all, his baby.

— John Naughton, writing about Tim Berners-Lee

The seeds of the Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire — better known in the Anglosphere as simply CERN — were planted amidst the devastation of post-World War II Europe by the great French quantum physicist Louis de Broglie. Possessing an almost religious faith in pure science as a force for good in the world, he proposed a new, pan-European foundation dedicated to exploring the subatomic realm. “At a time when the talk is of uniting the peoples of Europe,” he said, “[my] attention has turned to the question of developing this new international unit, a laboratory or institution where it would be possible to carry out scientific work above and beyond the framework of the various nations taking part. What each European nation is unable to do alone, a united Europe can do, and, I have no doubt, would do brilliantly.” After years of dedicated lobbying on de Broglie’s part, CERN officially came to be in 1954, with its base of operations in Geneva, Switzerland, one of the places where Europeans have traditionally come together for all manner of purposes.

The general technological trend at CERN over the following decades was the polar opposite of what was happening in computing: as scientists attempted to peer deeper and deeper into the subatomic realm, the machines they required kept getting bigger and bigger. Between 1983 and 1989, CERN built the Large Electron-Positron Collider in Geneva. With a circumference of almost seventeen miles, it was the largest single machine ever built in the history of the world. Managing projects of such magnitude, some of them employing hundreds of scientists and thousands of support staff, required a substantial computing infrastructure, along with many programmers and systems architects to run it. Among this group was a quiet Briton named Tim Berners-Lee.

Berners-Lee’s credentials were perfect for his role. He had earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from Oxford in 1976, only to find that pure science didn’t satisfy his urge to create practical things that real people could make use of. As it happened, both of his parents were computer scientists of considerable note; they had both worked on the University of Manchester’s Mark I computer, the world’s very first stored-program von Neumann machine. So, it was natural for their son to follow in their footsteps, to make a career for himself in the burgeoning new field of microcomputing. Said career took him to CERN for a six-month contract in 1980, then back to Geneva on a more permanent basis in 1984. Because of his background in physics, Berners-Lee could understand the needs of the scientists he served better than many of his colleagues; his talent for devising workable solutions to their problems turned him into something of a star at CERN. Among other projects, he labored long and hard to devise a way of making the thousands upon thousands of pages of documentation that were generated at CERN each year accessible, manageable, and navigable.

But, for all that Berners-Lee was being paid to create an internal documentation system for CERN, it’s clear that he began thinking along bigger lines fairly quickly. The same problems of navigation and discoverability that dogged his colleagues at CERN were massively present on the Internet as a whole. Information was hidden there in out-of-the-way repositories that could only be accessed using command-line-driven software with obscure command sets — if, that is, you knew that it existed at all.

His idea of a better way came courtesy of hypertext theory: a non-linear approach to reading texts and navigating an information space, built around associative links embedded within and between texts. First proposed by Vannevar Bush, the World War II-era MIT giant whom we briefly met in an earlier article in this series, hypertext theory had later proved a superb fit with a mouse-driven graphical computer interface which had been pioneered at Xerox PARC during the 1970s under the astute management of our old friend Robert Taylor. The PARC approach to user interfaces reached the consumer market in a prominent way for the first time in 1984 as the defining feature of the Apple Macintosh. And the Mac in turn went on to become the early hotbed of hypertext experimentation on consumer-grade personal computers, thanks to Apple’s own HyperCard authoring system and the HyperCard-driven laser discs and CD-ROMs that soon emerged from companies like Voyager.

The user interfaces found in HyperCard applications were surprisingly similar to those found in the web browsers of today, but they were limited to the curated, static content found on a single floppy disk or CD-ROM. “They’ve already done the difficult bit!” Berners-Lee remembers thinking. Now someone just needed to put hypertext on the Internet, to allow files on one computer to link to files on another, with anyone and everyone able to create such links. He saw how “a single hypertext link could lead to an enormous, unbounded world.” Yet no one else seemed to see this. So, he decided at last to do it himself. In a fit of self-deprecating mock-grandiosity, not at all dissimilar to J.C.R. Licklider’s call for an “Intergalactic Computer Network,” he named his proposed system the “World Wide Web.” He had no idea how perfect the name would prove.

He sat down to create his World Wide Web in October of 1990, using a NeXT workstation computer, the flagship product of the company Steve Jobs had formed after getting booted out of Apple several years earlier. It was an expensive machine — far too expensive for the ordinary consumer market — but supremely elegant, combining the power of the hacker-favorite operating system Unix with the graphical user interface of the Macintosh.

The NeXT computer on which Tim Berners-Lee created the foundations of the World Wide Web. It then went on to become the world’s first web server.

Progress was swift. In less than three months, Berners-Lee coded the world’s first web server and browser, which also entailed developing the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) they used to communicate with one another and the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) for embedding associative links into documents. These were the foundational technologies of the Web, which still remain essential to the networked digital world we know today.

The first page to go up on the nascent World Wide Web, which belied its name at this point by being available only inside CERN, was a list of phone numbers of the people who worked there. Clicking through its hypertext links being much easier than entering commands into the database application CERN had previously used for the purpose, it served to get Berners-Lee’s browser installed on dozens of NeXT computers. But the really big step came in August of 1991, when, having debugged and refined his system as thoroughly as he was able by using his CERN colleagues as guinea pigs, he posted his web browser, his web server, and documentation on how to use HTML to create web documents on Usenet. The response was not immediately overwhelming, but it was gratifying in a modest way. Berners-Lee:

People who saw the Web and realised the sense of unbound opportunity began installing the server and posting information. Then they added links to related sites that they found were complimentary or simply interesting. The Web began to be picked up by people around the world. The messages from system managers began to stream in: “Hey, I thought you’d be interested. I just put up a Web server.”

Tim Berners-Lee’s original web browser, which he named Nexus in honor of its host platform. The NeXT computer actually had quite impressive graphics capabilities, but you’d never know it by looking at Nexus.

In December of 1991, Berners-Lee begged for and was reluctantly granted a chance to demonstrate the World Wide Web at that year’s official Hypertext conference in San Antonio, Texas. He arrived with high hopes, only to be accorded a cool reception. The hypertext movement came complete with more than its fair share of stodgy theorists with rigid ideas about how hypertext ought to work — ideas which tended to have more to do with the closed, curated experiences of HyperCard than the anarchic open Internet. Normally modest almost to a fault, the Berners-Lee of today does allow himself to savor the fact that “at the same conference two years later, every project on display would have something to do with the Web.”

But the biggest factor holding the Web back at this point wasn’t the resistance of the academics; it was rather its being bound so tightly to the NeXT machines, which had a total user base of no more than a few tens of thousands, almost all of them at universities and research institutions like CERN. Although some browsers had been created for other, more popular computers, they didn’t sport the effortless point-and-click interface of Berners-Lee’s original; instead they presented their links like footnotes, whose numbers the user had to type in to visit them. Thus Berners-Lee and the fellow travelers who were starting to coalesce around him made it their priority in 1992 to encourage the development of more point-and-click web browsers. One for the X Window System, the graphical-interface layer which had been developed for the previously text-only Unix, appeared in April. Even more importantly, a Macintosh browser arrived just a month later; this marked the first time that the World Wide Web could be explored in the way Berners-Lee had envisioned on a computer that the proverbial ordinary person might own and use.

Amidst the organization directories and technical papers which made up most of the early Web — many of the latter inevitably dealing with the vagaries of HTTP and HTML themselves — Berners-Lee remembers one site that stood out for being something else entirely, for being a harbinger of the more expansive, humanist vision he had had for his World Wide Web almost from the start. It was a site about Rome during the Renaissance, built up from a traveling museum exhibition which had recently visited the American Library of Congress. Berners-Lee:

On my first visit, I wandered to a music room. There was an explanation of the events that caused the composer Carpentras to present a decorated manuscript of his Lamentations of Jeremiah to Pope Clement VII. I clicked, and was glad I had a 21-inch colour screen: suddenly it was filled with a beautifully illustrated score, which I could gaze at more easily and in more detail than I could have done had I gone to the original exhibit at the Library of Congress.

If we could visit this site today, however, we would doubtless be struck by how weirdly textual it was for being a celebration of the Renaissance, one of the most excitingly visual ages in all of history. The reality is that it could hardly have been otherwise; the pages displayed by Berners-Lee’s NeXT browser and all of the others could not mix text with images at all. The best they could do was to present links to images, which, when clicked, would lead to a picture being downloaded and displayed in a separate window, as Berners-Lee describes above.

But already another man on the other side of the ocean was working on changing that — working, one might say, on the last pieces necessary to make a World Wide Web that we can immediately recognize today.

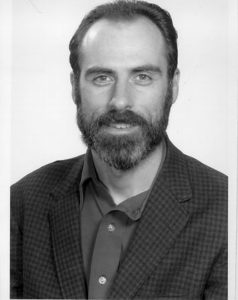

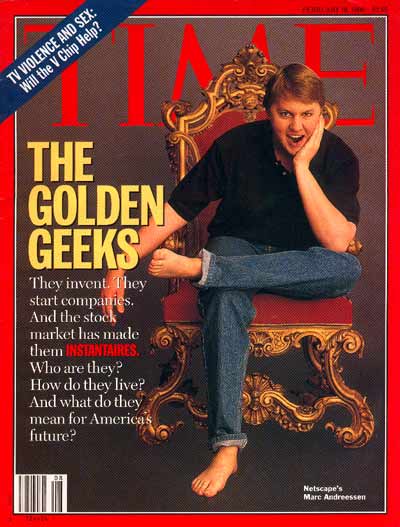

Marc Andreessen barefoot on the cover of Time magazine, creating the archetype of the dot-com entrepreneur/visionary/rock star.

Tim Berners-Lee was the last of the old guard of Internet pioneers. Steeped in an ethic of non-profit research for the abstract good of the human race, he never attempted to commercialize his work. Indeed, he has seemed in the decades since his masterstroke almost to willfully shirk the money and fame that some might say are rightfully his for putting the finishing touch on the greatest revolution in communications since the printing press, one which has bound the world together in a way that Samuel Morse and Alexander Graham Bell could never have dreamed of.

Marc Andreessen, by contrast, was the first of a new breed of business entrepreneurs who have dominated our discussions of the Internet from the mid-1990s until the present day. Yes, one can trace the cult of the tech-sector disruptor, “making the world a better place” and “moving fast and breaking things,” back to the dapper young Steve Jobs who introduced the Apple Macintosh to the world in January of 1984. But it was Andreessen and the flood of similar young men that followed him during the 1990s who well and truly embedded the archetype in our culture.

Before any of that, though, he was just a kid who decided to make a web browser of his own.

Andreessen first discovered the Web not long after Berners-Lee first made his tools and protocols publicly available. At the time, he was a twenty-year-old student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who held a job on the side at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, a research institute with close ties to the university. The name sounded very impressive, but he found the job itself to be dull as ditch water. His dissatisfaction came down to the same old split between the “giant brain” model of computing of folks like Marvin Minsky and the more humanist vision espoused in earlier years by people like J.C.R. Licklider. The NCSA was in pursuit of the former, but Andreessen was a firm adherent of the latter.

Bored out of his mind writing menial code for esoteric projects he couldn’t care less about, Andreessen spent a lot of time looking for more interesting things to do on the Internet. And so he stumbled across the fledgling World Wide Web. It didn’t look like much — just a screen full of text — but he immediately grasped its potential.

In fact, he judged, the Web’s not looking like much was a big part of its problem. Casting about for a way to snazz it up, he had the stroke of inspiration that would make him a multi-millionaire within three years. He decided to add a new tag to Berners-Lee’s HTML specification: “<img>,” for “image.” By using it, one would be able to show pictures inline with text. It could make the Web an entirely different sort of place, a wonderland of colorful visuals to go along with its textual content.

As conceptual leaps go, this one really wasn’t that audacious. The biggest buzzword in consumer computing in recent years — bigger than hypertext — had been “multimedia,” a catch-all term describing exactly this sort of digital mixing of content types, something which was now becoming possible thanks to the ever-improving audiovisual capabilities of personal computers since those primitive early days of the trinity of 1977. Hypertext and multimedia had actually been sharing many of the same digs for quite some time. The HyperCard authoring system, for example, boasted capabilities much like those which Andreessen now wished to add to HTML, and the Voyager CD-ROMs already existed as compelling case studies in the potential of interactive multimedia hypertext in a non-networked context.

Still, someone had to be the first to put two and two together, and that someone was Marc Andreessen. An only moderately accomplished programmer himself, he convinced a much better one, another NCSA employee named Eric Bina, to help him create his new browser. The pair fell into roles vaguely reminiscent of those of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak during the early days of Apple Computer: Andreessen set the agenda and came up with the big ideas — many of them derived from tireless trawling of the Usenet newsgroups to find out what people didn’t like about the current browsers — and Bina turned his ideas into reality. Andreessen’s relentless focus on the end-user experience led to other important innovations beyond inline images, such as the “forward,” “back,” and “refresh” buttons that remain so ubiquitous in the browsers of today. The higher-ups at NCSA eventually agreed to allow Andreessen to brand his browser as a quasi-official product of their institute; on an Internet still dominated by academics, such an imprimatur was sure to be a useful aid. In January of 1993, the browser known as Mosaic — the name seemed an apt metaphor for the colorful multimedia pages it could display — went up on NCSA’s own servers. After that, “it spread like a virus,” in the words of Andreessen himself.

The slick new browser and its almost aggressively ambitious young inventor soon came to the attention of Tim Berners-Lee. He calls Andreessen “a total contrast to any of the other [browser] developers. Marc was not so much interested in just making the program work as in having his browser used by as many people as possible.” But, lest he sound uncharitable toward his populist counterpart, he hastens to add that “that was, of course, what the Web needed.” Berners-Lee made the Web; the garrulous Andreessen brought it to the masses in a way the self-effacing Briton could arguably never have managed on his own.

About six months after Mosaic hit the Internet, Tim Berners-Lee came to visit its inventor. Their meeting brought with it the first palpable signs of the tension that would surround the World Wide Web and the Internet as a whole almost from that point forward. It was the tension between non-profit idealism and the urge to commercialize, to brand, and finally to control. Even before the meeting, Berners-Lee had begun to feel disturbed by the press coverage Mosaic was receiving, helped along by the public-relations arm of NCSA itself: “The focus was on Mosaic, as if it were the Web. There was little mention of other browsers, or even the rest of the world’s effort to create servers. The media, which didn’t take the time to investigate deeper, started to portray Mosaic as if it were equivalent to the Web.” Now, at the meeting, he was taken aback by an atmosphere that smacked more of a business negotiation than a friendly intellectual exchange, even as he wasn’t sure what exactly was being negotiated. “Marc gave the impression that he thought of this meeting as a poker game,” Berners-Lee remembers.

Andreessen’s recollections of the meeting are less nuanced. Berners-Lee, he claims, “bawled me out for adding images to the thing.” Andreessen:

Academics in computer science are so often out to solve these obscure research problems. The universities may force it upon them, but they aren’t always motivated to just do something that people want to use. And that’s definitely the sense that we always had of CERN. And I don’t want to mis-characterize them, but whenever we dealt with them, they were much more interested in the Web from a research point of view rather than a practical point of view. And so it was no big deal to them to do a NeXT browser, even though nobody would ever use it. The concept of adding an image just for the sake of adding an image didn’t make sense [to them], whereas to us, it made sense because, let’s face it, they made pages look cool.

The first version of Mosaic ran only on X-Windows, but, as the above would indicate, Andreessen had never intended for that to be the case for long. He recruited more programmers to write ports for the Macintosh and, most importantly of all, for Microsoft Windows, whose market share of consumer computing in the United States was crossing the threshold of 90 percent. When the Windows version of Mosaic went online in September of 1993, it motivated hundreds of thousands of computer owners to engage with the Internet for the first time; the Internet to them effectively was Mosaic, just as Berners-Lee had feared would come to pass.

The Mosaic browser. It may not look like much today, but its ability to display inline images was a game-changer.

At this time, Microsoft Windows didn’t even include a TCP/IP stack, the software layer that could make a machine into a full-fledged denizen of the Internet, with its own IP address and all the trimmings. In the brief span of time before Microsoft remedied that situation, a doughty Australian entrepreneur named Peter Tattam provided an add-on TCP/IP stack, which he distributed as shareware. Meanwhile other entrepreneurs scrambled to set up Internet service providers to provide the unwashed masses with an on-ramp to the Web — no university enrollment required! — and the shelves of computer stores filled up with all-in-one Internet kits that were designed to make the whole process as painless as possible.

The unabashed elitists who had been on the Internet for years scorned the newcomers, but there was nothing they could do to stop the invasion, which stormed their ivory towers with overwhelming force. Between December of 1993 and December of 1994, the total amount of Web traffic jumped by a factor of eight. By the latter date, there were more than 10,000 separate sites on the Web, thanks to people all over the world who had rolled up their sleeves and learned HTML so that they could get their own idiosyncratic messages out to anyone who cared to read them. If some (most?) of the sites they created were thoroughly frivolous, well, that was part of the charm of the thing. The World Wide Web was the greatest leveler in the history of media; it enabled anyone to become an author and a publisher rolled into one, no matter how rich or poor, talented or talent-less. The traditional gatekeepers of mass media have been trying to figure out how to respond ever since.

Marc Andreessen himself abandoned the browser that did so much to make all this happen before it celebrated its first birthday. He graduated from university in December of 1993, and, annoyed by the growing tendency of his bosses at NCSA to take credit for his creation, he decamped for — where else? — Silicon Valley. There he bumped into Jim Clark, a huge name in the Valley, who had founded Silicon Graphics twelve years earlier and turned it into the biggest name in digital special effects for the film industry. Feeling hamstrung by Silicon Graphics’s increasing bureaucracy as it settled into corporate middle age, Clark had recently left the company, leading to much speculation about what he would do next. The answer came on April 4, 1994, when he and Marc Andreessen founded Mosaic Communications in order to build a browser even better than the one the latter had built at NCSA. The dot-com boom had begun.

(Sources: the books A Brief History of the Future: The Origins of the Internet by John Naughton, From Gutenberg to the Internet: A Sourcebook on the History of Information Technology edited by Jeremy M. Norman, A History of Modern Computing (2nd ed.) by Paul E. Ceruzzi, Communication Networks: A Concise Introduction by Jean Walrand and Shyam Parekh, Weaving the Web by Tim Berners-Lee, How the Web was Born by James Gillies and Robert Calliau, and Architects of the Web by Robert H. Reid. InfoWorld of August 24 1987, September 7 1987, April 25 1988, November 28 1988, January 9 1989, October 23 1989, and February 4 1991; Computer Gaming World of May 1993.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | When he first stated his law in 1965, Moore actually proposed a doubling every single year, but revised his calculations in 1975. |

|---|