Stu Galley, a man who would come to unabashedly love the games Infocom created, who would author the almost naively idealistic “Implementor’s Creed” to describe the job he and his fellow Imps did, took quite a long time to discover his passion. When he first saw the Zork game that some of the other hackers in MIT’s Dynamic Modeling Group had created, he thought it clever but little else. He had no interest in fantasy fiction or Dungeons and Dragons, and no particular interest in exploring beyond Zork‘s first few rooms. Some of his disinterest may have been generational. Already in his mid-thirties when Zork was begun, he was five to ten years older than the people who made it. That’s not a huge gap, but it was enough to place him at a somewhat different stage of life, one where such idle amusements might not have quite so much appeal in light of his wife and young son.

When asked to become a founder of Infocom, he signed on because he had a lot of respect for the talents of the others. He thought they just might come up with something — who knew what? — really great, and he didn’t want to be kicking himself over the lost opportunity in five years. During this early period Galley, like most of the founders, did this or that for the company as time and inclination allowed, but kept it very much ancillary to his main working life. His official role at Infocom was to serve as treasurer. He also pitched in to help with odd jobs here and there: an experienced technical writer, he wrote the original manual for the commercial Zork, and helped Mike Dornbrook to set up and administer the mailing list that would morph into The Zork Users Group. But he mostly remained on the periphery, not quite ready to commit too much energy to the venture. Then came an epiphany.

Very early in 1982 Galley agreed to another of those odd jobs: to do some testing on Marc Blank’s new mystery, Deadline. Galley was blown away by the game for much the same reason it would soon cause a sensation in the world of adventure gaming in general. He still recalls vividly today how, when exploring the Robner house for the first time, he heard a phone ring in the other room but missed the call. Restarting, he made sure to be near a phone when the time came, and heard Mrs. Robner having a clipped conversation with her lover. That “blew his mind.” Here was a realistic, dynamic world to inhabit, one which struck him as far more interesting than the vast, empty dungeon of Zork with its static, arbitrary puzzles. “I could relive this story over and over and eventually, by looking at it from different angles and connecting the dots, find out what was really going on.” Galley was hooked at last.

In light of Deadline‘s commercial success, another mystery was obviously warranted. With some input from Dave Lebling, Blank began sketching out plans for a sequel almost immediately. He already had a clever gimmick in mind: the player would be invited to his home by the victim, where she would actually witness the murder in the opening scenes of the game. Nevertheless, it still wouldn’t be clear who was actually responsible. Unfortunately, Blank was absolutely swamped with other work: putting together Zork III, helping Mike Berlyn get up to speed on ZIL and ensuring he had the tools he needed for the game that would become Suspended, doing an ever-escalating series of interviews and PR junkets, sorting out business issues with the board. The game, to be called Invitation to Murder, remained only an outline of a few typewritten pages into the fall. That’s when it occurred to Blank, who was forever looking for ways to cajole his fellow founders into taking a more active role, to offer the outline to Galley, who still had stars in his eyes over his Deadline experience. Galley quickly agreed, and in October of 1982, while still only moonlighting at Infocom, started to work.

Working from a stripped-down skeleton of the original Deadline code, Galley gradually built a playable game over the next few months. Along the way, the project had one of the effects for which Blank had hoped: Galley was so inspired by the new work that he quit MIT and came to Infocom full-time before the year was out. In late January Infocom sat down with their ever-supportive advertising agency of G/R Copy to discuss the upcoming game. Just as they had with Deadline, G/R quickly replaced the original title with something much more punchy and direct: simply The Witness. Both Mike Berlyn and G/R also suggested that the time period and the tone be changed. They suggested that, rather than the ostensible present of Deadline, Galley move the game to the golden age of mystery, the 1930s. In retrospect this was a natural change. As I noted when writing about Deadline, that game felt like a product of the golden age anyway; The Witness would merely make it official. If anything the more important suggestion was to change the style to differentiate the new game from Deadline. If Deadline was a cozy mystery in the tradition of Agatha Christie, The Witness could be Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett, a hardboiled tale of noirish intrigue.

Galley didn’t have much experience with this branch of the mystery canon, but, as he later put it, as soon as he started to read The Big Sleep he was convinced. Instead of the stately, blue-blooded Connecticut of Deadline, The Witness would take place in 1938 Los Angeles, at the peak of pre-war Hollywood’s loose glamor and danger. Galley lost himself in period research. In addition to the classic crime fiction of the period, he drew from a Sears catalog and other advertisements from the era, a 1937 encyclopedia, and The Dictionary of American Slang (to get the characters’ language right). He went so far as to track down a radio schedule for February 18, 1938, the evening of the crime, and make sure that the radio inside the house played the correct program from minute to minute.

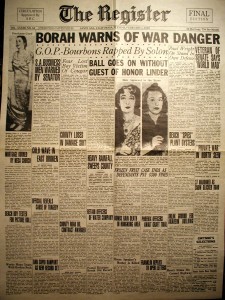

In the tradition of Deadline, the packaging of The Witness would be a major part of the experience. Accordingly, Infocom began working with G/R on it months before the game’s projected release. Already back when outlining the game Blank had proposed including a newspaper with articles giving background information on the victim and the suspects, another direct lift from the old Dennis Wheatley crime dossiers (a fold-out newspaper had been the showstopping centerpiece of Who Killed Robert Prentice?). With the newfound historical context, G/R now ran with the idea to create one of the most impressive feelies Infocom would ever release. They found a newspaper in the Los Angeles area, The Register of Santa Ana, who agreed to share several editions from the period on microfiche. They then had the whole thing typeset once again, with a couple of new, game-specific articles slyly inserted. As Galley later noted, some of the real stories from the newspaper (“Fear Lost Boy Victim of Cougar”; “Works Many Years with Broken Neck”; “Pajama ‘Parade’ Results as Toy Catches on Fire”) were more bizarre than anything they could have come up with on their own. Printed on perfectly yellowed cheap newsprint, the final result is a triumph.

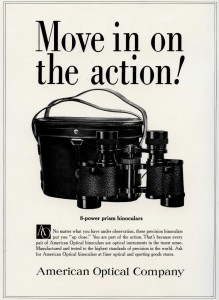

G/R contacted Western Union for help recreating a telegram from the period. Galley and G/R, who clearly had a great deal of fun with this project, scoured old magazines and catalogs for advertisements to include in the faux-detective magazine that serves as the manual. G/R was even able to get some of their other clients, such as American Optical, to loan their old adverts to the effort.

For the obligatory physical prop, the equivalent to the pills included in the Deadline package, they added a matchbook with a cryptic phone number scrawled on the inside. Taken all together, The Witness outclasses even Deadline in its packaging. It’s almost enough to make the actual game it’s supporting feel just a bit underwhelming in comparison.

It’s not that there’s anything dramatically wrong with The Witness, just that after such a build-up the actual case at its heart is maybe not quite so intriguing as one might wish. The solution, when you uncover it, is thoroughly absurd, not at all unusual in this genre, but not ultimately all that interesting in spite of its absurdity. Perhaps the biggest problem is that there just aren’t enough suspects nor enough juicy secrets to be discovered about them. There are only three possible murderers, and one of those has been caught red-handed fleeing from the crime scene — which, as anyone who’s ever read a mystery novel should know, pretty much rules him out from the get-go. Combined with the smallest map of any Infocom game to date — some 30 rooms, most of them empty and unnecessary to even visit — that’s likely to leave one rather nonplussed at the end, asking, “Is that really it?” It’s certainly one of the shortest games Infocom would ever release.

But that was more of a problem in 1983, when people were spending $30 or $40 to buy The Witness, than it is today, when we can enjoy it on its own terms. And in that spirit there’s a lot to recommend it. Although its case is not so intriguing, I actually found The Witness to be a better, more satisfying experience than Deadline was when my wife and I recently played it, for the simple reason that it’s fair. It’s blessedly solvable with some careful thought and attention, without needing to do anything absurd like DIG for no apparent reason. When we apprehended the killer, sans any hints at all, it was a great feeling, a testament to Infocom’s evolving design craft and the increasing involvement by this point of the in-house and out-of-house testers, who were now shaking down the designs and providing vital reality checks to the Imps. If anything, some might consider The Witness too easy, but that’s always been a more forgivable sin than the alternative of hardness-through-unfairness in my book.

Galley, who had never written a word of fiction before starting on The Witness, does a pretty good job with it here. The opening lines leave no doubt about the genre we’re in for:

Somewhere near Los Angeles. A cold Friday evening in February 1938. In this climate, cold is anywhere below about fifty degrees. Storm clouds are swimming across the sky, their bottoms glowing faintly from the city lights in the distance. A search light pans slowly under the clouds, heralding another film premiere. The air seems expectant, waiting for the rain to begin, like a cat waiting for the ineffable moment to ambush.

The constrained geography and relative paucity of interactable objects have the positive side effect of giving more space for exposition. The opening stages of the game in particular, before you witness the murder that really kicks off the case in earnest, are surprisingly florid, in a way that no previous Infocom game had been. It’s little surprise that so many tended to latch onto The Witness even more than Deadline as a harbinger of a new type of literature.

Still, The Witness‘s historical reputation has always suffered in comparison to that of Deadline, likely the inevitable result of being the follow-up to such a great, audacious leap. For another likely reason for its less than stellar ranking in the Infocom canon today we can look again to those wonderful feelies, which were both such an important part of the experience and, in the case of the newspaper, almost uniquely hard to recreate in a PDF document or the like. To the extent that these factors may blind people to The Witness‘s real merits — it’s not a masterpiece, but it is a solid piece of craftsmanship — that’s a shame.

Deadline also somewhat overshadowed The Witness on the sales charts. Release in June of 1983, The Witness sold a little over 25,000 copies before the end of the year, then some 35,000 the next, oddly failing to keep pace even when quite new with the older Deadline. Still, those numbers were more than enough to make it profitable for Infocom. And for anyone looking to get started with the Infocom mysteries today just for fun (as opposed to historical research), it’s definitely the one I’d recommend you play.

Nathan

March 22, 2013 at 5:47 pm

To someone used to Zork and Deadline, The Witness seems a little like a technological throwback. IIRC, it doesn’t understand GET ALL. There are weird inconsistencies with objects inside containers, and some actions work even in the wrong room! I think this game missed out on some of Infocom’s accumulated wisdom, struggling with technical problems that had already been solved in earlier games.

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2013 at 9:43 am

I just checked, and you’re right — The Witness doesn’t know the word “all.” That’s doubly strange when we consider that it was built from the skeleton of the Deadline source, which — yes, I checked that also — does understand “all.”

That said, and in spite of the rather lengthy bug list to which you linked, the first release of Deadline struck me as a player as much more buggy than the first release of The Witness. One thing we should keep in mind when making comparisons like this is that many Infocom games were updated several times post-release to swat bugs and fix glitches. The earliest games (pre-1983) all particularly benefited from this commitment. These games in their original form received comparatively little testing or player feedback before release. Once Infocom got their QA department and a methodical testing regimen in place by the beginning of 1983, these older releases were substantively updated to bring them up to current QA standards. So, we have to check serial numbers before we go too far with comparisons like this, to make sure we’re always comparing apples to apples.

Adam Thornton

March 22, 2013 at 10:38 pm

It’s also totally possible to win without having figured it out at all.

I played for the first time a few years ago. I didn’t think I had enough information, but I thought that making an arrest (I had a suspect but didn’t think I had anywhere near enough evidence) would lose me the game but also give me a valuable hint about where I should focus my efforts.

Imagine my surprise when I got a conviction.

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2013 at 9:46 am

I can see how that could happen. From our exposure to the mystery genre in other media we’re conditioned to expect a smoking gun that seals the case. The Witness doesn’t have that, just a series of smaller data points that add up to point in a particular direction. That’s possibly more realistic, but may also make it less satisfying as a genre exercise.

Nathanael

March 6, 2021 at 6:39 am

I, quite frustratingly, had figured out the method of the crime and the murderer but had apparently not collected the right piece of evidence to get a conviction. Had to check the hints.

The whole evidence schema was weak in both Deadline and The Witness; understandable that it was eliminated for The Suspect and Moonmist.

Nathanael

March 6, 2021 at 6:43 am

…and I should add that despite that, I loved The Witness for its incredibly detailed atmosphere. Tone and setting. Going down obviously-hopeless paths like never ringing the doorbell is *interesting*.

Keith Palmer

March 23, 2013 at 1:42 am

In my first phase of “wanting to know more about these games I hadn’t had a chance to play” (a few years before “The Lost Treasures of Infocom” came out), I came across an article in an old copy of the last issue of Radio Shack’s house publication describing The Witness, Planetfall, and Zork I, the three Infocom games you could buy through them at the time. I suppose that makes it stick a bit more in my memory, helped along by its distinctive setting. I’ve never played very far into any of the big, complicated mysteries, though… maybe it’s not a genre I’m especially interested in in general, or perhaps by the time I first got to them I was feeling bad about always turning to “LToI’s” awkward hint book the first time I got stuck.

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2013 at 9:53 am

I’d say your experience was fairly typical. As we’ll see, Infocom saw diminishing commercial returns from each successive mystery. After the novelty of Deadline wore off, it really did seem that most people found the very different demands the mysteries made upon them less enjoyable than the more traditional games. Infocom never was able to find a way around the “play it over and over until you learn where you need to be and what you need to do at each step” model. Many players just really, really dislike having to play that way.

Healy

March 23, 2013 at 4:32 am

Man I am just reading through the feelies and already I love this game. Such charm, such character! One question: is the phrase “OKLIT VOS FROB VEN-VEN DOOBEL-DEE” in the doctor’s article a reference to anything? It could be nonsense, but it seems from the context it could be a reference to some computer command, or possibly magic words from another game.

(And while I’m on the subject, I just LOVE the detectives’ patronizing attitude towards this guy. You can tell he’s an unwelcome interloper to their ‘zine.)

Jimmy Maher

March 23, 2013 at 9:56 am

Yeah, The Witness just might have my favorite group of feelies. They’re not as flashy or as obviously clever (read: gimmicky) as some of the others, but if the objective of the exercise is to immerse the player in a certain setting and genre, it’s hard to imagine doing it better. The biggest problem with them is that they’re almost more clever and satisfying than the actual game.

I don’t know what the message means. Knowing the personalities at Infocom, thought, I assume it means something, relates to some in-joke somewhere. But nothing I can apply directly to the game…

Zurlocker

March 24, 2013 at 6:10 pm

I think The Witness is one of the best from Infocom. Great feelies, good atmosphere and very approachable for newbies. Yes it has it’s quirks and is quite short but still a lot of fun.

–Zack

David Simon

September 3, 2013 at 12:08 pm

Aw, the “Implementor’s Creed” link is broken. :-(

Jimmy Maher

September 3, 2013 at 1:14 pm

It seems that Peter Scheyen’s long-lived Infocom site has left us. I fixed the link thanks to archive.org. Will try to do the same for the other links there (of which I suspect there must be quite a few) soon.

Peter Orvetti

July 24, 2019 at 9:56 am

“The Witness” is the only Infocom game I ever completed without hints or Invisiclues. (I never played the “introductory” games like “Wishbringer” and “Seastalker”, which is odd because we owned almost all the games up to about 1985.)

I remember finishing it about a day after getting it, and being puzzled, thinking there must be more because I wasn’t very good at the games. (I’m still not.)

Ben

December 6, 2020 at 6:45 pm

from get-go -> from the get-go

Jimmy Maher

December 7, 2020 at 1:33 pm

Thanks!

Greg

February 16, 2022 at 12:53 pm

Greeting to all! I replayed The Witness last night after about 20 years, lol! I had first bought the game in 1983 at the tender age of 13 (for my Atari 800). However, I have this nagging question. On my original Atari version, I had gotten Monica to completely break down and confess to the murder!

Upon replaying the game on WinFrotz, it seems I cannot get past her saying ” He was dying…” What I mean is that I cannot seem to get a full confession from her as in the old Atari version. has this happened to anyone else? Was there a change in the game from version to version? Or did I just do something in the Atari version (maybe perfectly presented all the evidence) which i failed to do now? Many thanks to Jimmy for this great website!

Lisa H.

February 23, 2022 at 6:26 pm

According to the Invisiclues, it depends on the order in which you do things. Without actually pasting the spoiler text here (I don’t think I can do CSS span in comments to hide it…), you can use Parchment to read a .z5 file of the Invisiclues like so: https://iplayif.com/?story=http://infodoc.plover.net/hints/witness.z5 and see the answers for the question “How do I prove my case to the satisfaction of a jury?”

Lisa H.

February 23, 2022 at 6:28 pm

Or of course you can just download the .z5 file and load it in WinFrotz, of course. Heheh, I’m at work and don’t have WinFrotz installed here (naturally) so I was like “umm how else can I read this…” ;)

Vince

December 30, 2023 at 10:44 am

Just played it… I must say I liked it way less than Deadline.

I honestly think Deadline deserves a place in the Hall of Fame more than The Witness, not just because of coming first but also as just a better mystery game (I haven’t played Suspect, yet).

(heavy spoilers below)

I got the best ending after 2/3 hours of play (mapping the house as well), but reading the author summary afterwards I realized I didn’t get most of the plot.

I missed completely Linder’s plan and Phong’s involvement in it; I thought it was all Monica’s doing and I thought Stiles’s appearance was completely by chance.

I think the game should have been really benefited from expecting the player to find more proof and explain how how the whole think panned out.

As it stands, I believe all you need to do is:

– Find the gunpowder in the clock keyhole and have Duffy analyze it

– Surprise Monica when she recovers the gun from the clock and accuse her of murder

– Ask her about her mother (she doesn’t even tell you anything significant, but apparently works as “found the motive” trigger).

– Arrest her

A lot of cool stuff you could find about the boots, the second gun, the workshop is completely optional and not needed to get the best ending.

I’m not sure if it can be said that a game respects players’ time if it just hands you a good ending that easy.