In April of 1988, Brian Moriarty of Infocom flew from the East Coast to the West to attend the twelfth West Coast Computer Faire and the first ever Computer Game Developers Conference. Hard-pressed from below by the slowing sales of their text adventures and from above by parent company Activision’s ever more demanding management, Infocom didn’t have the money to pay for Moriarty’s trip. He therefore had to go on his own dime, a situation which left him, as he would later put it, very “grumpy” about the prospect of his ongoing employment by the very company at which he had worked so desperately to win a spot just a few years before.

The first West Coast Computer Faire back in 1977 had hosted the public unveiling of the Apple II and the Commodore PET, thus going down in hacker lore as the moment when the PC industry was truly born. By 1988, the Faire wasn’t the hugely important gathering it once had been, having been largely superseded on the industry’s calendar by glitzier events like the Consumer Electronics Show. Nevertheless, its schedule had its interesting entries, among them a lecture by Chris Crawford, the founder of the Computer Game Developers Conference which Moriarty would attend the next day. Moriarty recalls showing up a little late to Crawford’s lecture, scanning the room, and seeing just one chair free, oddly on the first row. He rushed over to take it, and soon struck up a conversation with the man sitting next to him, whom he had never met before that day. As fate would have it, his neighbor’s name was Noah Falstein, and he worked for Lucasfilm Games.

Attendees to the first ever Computer Game Developers Conference. Brian Moriarty is in the reddish tee-shirt at center rear, looking cool in his rock-star shades.

Falstein knew and admired Moriarty’s work for Infocom, and knew likewise, as did everyone in the industry, that things hadn’t been going so well back in Cambridge for some time now. His own Lucasfilm Games was in the opposite position. After having struggled since their founding back in 1982 to carve out an identity for themselves under the shadow of George Lucas’s Star Wars empire, by 1988 they finally had the feeling of a company on the rise. With Maniac Mansion, their big hit of the previous year, Falstein and his colleagues seemed to have found in point-and-click graphical adventures a niche that was both artistically satisfying and commercially rewarding. They were already hard at work on the follow-up to Maniac Mansion, and Lucasfilm Games’s management had given the go-ahead to look for an experienced adventure-game designer to help them make more games. As one of Infocom’s most respected designers, Brian Moriarty made an immediately appealing candidate, not least in that Lucasfilm Games liked to see themselves as the Infocom of graphical adventures, emphasizing craftsmanship and design as a way to set themselves apart from the more slapdash games being pumped out in much greater numbers by their arch-rivals Sierra.

For his part, Moriarty was ripe to be convinced; it wasn’t hard to see the writing on the wall back at Infocom. When Falstein showed him some photographs of Lucasfilm Games’s offices at Skywalker Ranch in beautiful Marin County, California, and shared stories of rubbing elbows with movie stars and casually playing with real props from the Star Wars and Indiana Jones movies, the contrast with life inside Infocom’s increasingly empty, increasingly gloomy offices could hardly have been more striking. Then again, maybe it could have been: at his first interview with Lucasfilm Games’s head Steve Arnold, Moriarty was told that the division had just two mandates. One was “don’t lose money”; the other was “don’t embarrass George Lucas.” Anything else — like actually making money — was presumably gravy. Again, this was music to the ears of Moriarty, who like everyone at Infocom was now under constant pressure from Activision’s management to write games that would sell in huge numbers.

Brian Moriarty arrived at Skywalker Ranch for his first day of work on August 1, 1988. As Lucasfilm Games’s new star designer, he was given virtually complete freedom to make whatever game he wanted to make.

Noah Falstein in Skywalker Ranch’s conservatory. This is where the Games people typically ate their lunches, which were prepared for them by a gourmet chef. There were definitely worse places to work…

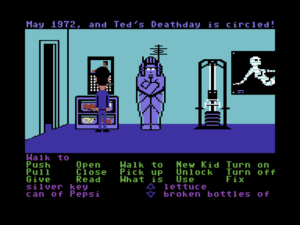

For all their enthusiasm for adventure games, the other designers at Lucasfilm were struggling a bit at the time to figure out how to build on the template of Maniac Mansion. Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, David Fox’s follow-up to Ron Gilbert’s masterstroke, had been published just the day before Moriarty arrived at Skywalker Ranch. It tried a little too obviously to capture the same campy charm, whilst, in typical games-industry fashion, trying to make it all better by making it bigger, expanding the scene of the action from a single night spent in a single mansion to locations scattered all around the globe and sometimes off it. The sense remained that Lucasfilm wanted to do things differently from Sierra, who are unnamed but ever-present — along with a sly dig at old-school rivals like Infocom still making text adventures — within a nascent manifesto of three paragraphs published in Zak McKracken‘s manual, entitled simply “Our Game Design Philosophy.”

We believe that you buy games to be entertained, not to be whacked over the head every time you make a mistake. So we don’t bring the game to a screeching halt when you poke your nose into a place you haven’t visited before. In fact, we make it downright difficult to get a character “killed.”

We think you’d prefer to solve the game’s mysteries by exploring and discovering. Not by dying a thousand deaths. We also think you like to spend your time involved in the story. Not typing in synonyms until you stumble upon the computer’s word for a certain object.

Unlike conventional computer adventures, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders doesn’t force you to save your progress every few minutes. Instead, you’re free to concentrate on the puzzles, characters, and outrageous good humor.

Worthy though these sentiments were, Lucasfilm seemed uncertain as yet how to turn them into practical rules for design. Ironically, Zak McKracken, the game with which they began publicly articulating their focus on progressive design, is the most Sierra-like Lucasfilm game ever made, with the sheer nonlinear sprawl of the thing spawning inevitable confusion and yielding far more potential dead ends than its designer would likely wish to admit. While successful enough in its day, it never garnered the love that’s still accorded to Maniac Mansion today.

Lucasfilm Games’s one adventure of 1989 was a similarly middling effort. A joint design by Gilbert, Falstein, and Fox, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure — an Action Game was also made — marked the first time since Labyrinth that the games division had been entrusted with one of George Lucas’s cinematic properties. They don’t seem to have been all that excited at the prospect. The game dutifully walks you through the plot you’ve already watched unfold on the silver screen, without ever taking flight as a creative work in its own right. The Lucasfilm “Game Design Philosophy” appears once again in the manual in almost the exact same form as last time, but once again the actual game hews to this ideal imperfectly at best, with, perhaps unsurprisingly given the two-fisted action movie on which it’s based, lots of opportunities to get Indy killed and have to revert to one of those save files you supposedly don’t need to create.

So, the company was rather running to stand still as Brian Moriarty settled in. They were determined to evolve their adventure games in design terms to match the strides Sierra was making in technology, but were uncertain how to actually go about the task. Moriarty wanted to make his own first work for Lucasfilm a different, more somehow refined experience than even the likes of Maniac Mansion. But how to do so? In short, what should he do with his once-in-a-lifetime chance to make any game he wanted to make?

Flipping idly through a computer magazine one day, he was struck by an advertisement that prominently featured the word “loom.” He liked the sound of it; it reminded him of other portentous English words like “gloom”, “doom,” and “tomb.” And he liked the way it could serve as either a verb or a noun, each with a completely different meaning. In a fever of inspiration, he sat down and wrote out the basis of the adventure game he would soon design, about a Loom which binds together the fabric of reality, a Guild of Weavers which uses the Loom’s power to make magic out of sound, and Bobbin Threadbare, the “Loom Child” who must save the Loom — and thus the universe — from destruction before it’s too late. It would be a story and a game with the stark simplicity of fable.

Simplicity, however, wasn’t exactly trending in the computer-games industry of 1988. Since the premature end of the would-be Home Computer Revolution of the early 1980s, the audience for computer games had grown only very slowly. Publishers had continued to serve the same base of hardcore players, who lusted after ever more complex games to take advantage of the newest hardware. Simulations had collected ever more buttons and included ever more variables to keep track of, while strategy games had gotten ever larger and more time-consuming. Nor had adventure games been immune to the trend, as was attested by Moriarty’s own career to date. Each of his three games for Infocom had been bigger and more difficult than the previous, culminating in his adventure/CRPG hybrid Beyond Zork, the most baroque game Infocom had made to date, with more options for its onscreen display alone than some professional business applications. Certainly plenty of existing players loved all this complexity. But did all games really need to go this way? And, most interestingly, what about all those potential players who took one look at the likes of Beyond Zork and turned back to the television? Moriarty remembered a much-discussed data point that had emerged from the surveys Infocom used to send to their customers: the games people said were their favorites overlapped almost universally with those they said they had been able to finish. In keeping with this trend, Moriarty’s first game for Infocom, which had been designed as an introduction to interactive fiction for newcomers, had been by far his most successful. What, he now thought, if he used the newer hardware at his disposal in the way that Apple has historically done, in pursuit of simplicity rather than complexity?

Lucasfilm Games’s current point-and-click interface, while undoubtedly the most painless in the industry at the time, was nevertheless far too complicated for Moriarty’s taste, still to a large extent stuck in the mindset of being a graphical implementation of the traditional text-adventure interface rather than treating the graphical adventure as a new genre in its own right. Thus the player was expected to first select a verb from a list at the bottom of the screen and then an object to which to apply it. The interface had done the job well enough to date, but Moriarty felt that it would interfere with the seamless connection he wished to build between the player sitting there before the screen and the character of Bobbin Threadbare standing up there on the screen. He wanted something more immediate, more intuitive — preferably an interface that didn’t require words at all. He envisioned music as an important part of his game: the central puzzle-solving mechanic would involve the playing of “drafts,” little sequences of notes created with Bobbin’s distaff. But he wanted music to be more than a puzzle-solving mechanic. He wanted the player to be able to play the entire game like a musical instrument, wordlessly and beautifully. He was thus thrilled when he peeked under the hood of Lucasfilm’s SCUMM adventure-game engine and found that it was possible to strip the verb menu away entirely.

Some users of Apple’s revolutionary HyperCard system for the Macintosh were already experimenting with wordless interfaces. Within weeks of HyperCard’s debut, a little interactive storybook called Inigo Gets Out, “programmed” by a non-programmer named Amanda Goodenough, had begun making the rounds, causing a considerable stir among industry insiders. The story of a house cat’s brief escape to the outdoors, it filled the entire screen with its illustrations, responding intuitively to single clicks on the pictures. Just shortly before Moriarty started work at Lucasfilm Games, Rand and Robyn Miller had taken this experiment a step further with The Manhole, a richer take on the concept of an interactive children’s storybook. Still, neither of these HyperCard experiences quite qualified as a game, and Moriarty and Lucasfilm were in fact in the business of making adventure games. Loom could be simple, but it had to be more than a software toy. Moriarty’s challenge must be to find enough interactive possibility in a verb-less interface to meet that threshold.

In response to that challenge, Moriarty created an interface that stands out today as almost bizarrely ahead of its time; not until years later would its approach be adopted by graphic adventures in general as the default best way of doing things. Its central insight, which it shared with the aforementioned HyperCard storybooks, was the realization that the game didn’t always need the player to explicitly tell it what she wanted to do when she clicked a certain spot on the onscreen picture. Instead the game could divine the player’s intention for itself, based only on where she happened to be clicking. What was sacrificed in the disallowing of certain types of more complex puzzles was gained in the creation of a far more seamless, intuitive link between the player, the avatar she controlled, and the world shown on the screen.

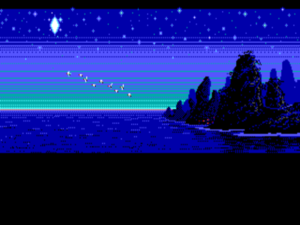

The brief video snippet above shows Loom‘s user interface in its entirety. You make Bobbin walk around by clicking on the screen. Hovering the mouse over an object or character with which Bobbin can interact brings up an image of that object or character in the bottom right corner of the screen; double-clicking the same “hot spot” then causes Bobbin to engage, either by manipulating an object in some way or by talking to another character. Finally, Bobbin can cast “spells” in the form of drafts by clicking on the musical staff at the bottom of the screen. In the snippet above, the player learns the “open” draft by double-clicking on the egg, an action which in this case results in Bobbin simply listening to it. The player and Bobbin then immediately cast the same draft to reveal within the egg his old mentor, who has been transformed into a black swan.

Moriarty seemed determined to see how many of the accoutrements of traditional adventure games he could strip away and still have something that was identifiable as an adventure game. In addition to eliminating menus of verbs, he also excised the concept of an inventory; throughout the game, Bobbin carries around with him nothing more than the distaff he uses for weaving drafts. With no ability to use this object on that other object, the only puzzle-solving mechanic that’s left is the magic system. In the broad strokes, magic in Loom is very much in the spirit of Infocom’s Enchanter series, in which you collect spells for your spell book, then cast them to solve puzzles that, more often than not, reward you with yet more spells. In Loom the process is essentially the same, except that you’re collecting musical drafts to weave on your distaff rather than spells for your spell book. And yet this musical approach to spell weaving is as lovely as a game mechanic can be. Lucasfilm thoughtfully included a “Book of Patterns” with the game, listing the drafts and providing musical staffs on which you can denote their sequences of notes as you discover them while playing.

The audiovisual aspect of Loom was crucial to capturing the atmosphere of winsome melancholia Moriarty was striving for. Graphics and sound were brand new territory for him; his previous games had consisted of nothing but text. Fortunately, the team of artists that worked with him grasped right away what was needed. Each of the guilds of craftspeople which Bobbin visits over the course of the game is marked by its own color scheme: the striking emerald of the Guild of Glassmakers, the softer pastoral greens of the Guild of Shepherds, the Stygian reds of the Guild of Blacksmiths, and of course the lovely, saturated blues and purples of Bobbin’s own Guild of Weavers. This approach came in very handy for technical as well as thematic reasons, given that Loom was designed for EGA graphics of just 16 onscreen colors.

The overall look of Loom was hugely influenced by the 1959 Disney animated classic Sleeping Beauty, with many of the panoramic shots in the game dovetailing perfectly with scenes from the film. Like Sleeping Beauty, Loom was inspired and accompanied by the music of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whom Moriarty describes as his “constant companion throughout my life”; while Sleeping Beauty draws from Tchaikovsky’s ballet of the same name, Loom draws from another of his ballets, Swan Lake. Loom sounds particularly gorgeous when played through a Roland MT-32 synthesizer board — an experience that, given the $600 price tag of the Roland, far too few players got to enjoy back in the day. But regardless of how one hears it, it’s hard to imagine Loom without its classical soundtrack. Harking back to Hollywood epics like 2001: A Space Odyssey, the MT-32 version of Loom opens with a mood-establishing orchestral overture over a blank screen.

To provide the final touch of atmosphere, Moriarty walked to the other side of Skywalker Ranch, to the large brick building housing Skywalker Sound, and asked the sound engineers in that most advanced audio-production facility in the world if they could help him out. Working from a script written by Moriarty and with a cast of voice actors on loan from the BBC, the folks at Skywalker Sound produced a thirty-minute “audio drama” setting the scene for the opening of the game; it was included in the box on a cassette. Other game developers had occasionally experimented with the same thing as a way of avoiding having to cover all that ground in the game proper, but Loom‘s scene-setter stood out for its length and for the professional sheen of its production. Working for Lucasfilm did have more than a few advantages.

If there’s something to complain about when it comes to Loom the work of interactive art, it must be that its portentous aesthetics lead one to expect a thematic profundity which the story never quite attains. Over the course of the game, Bobbin duly journeys through Moriarty’s fairy-tale world and defeats the villain who threatens to rip asunder the fabric of reality. The ending, however, is more ambiguous than happy, with only half of the old world saved from the Chaos that has poured in through the rip in the fabric. I don’t object in principle to the idea of a less than happy ending (something for which Moriarty was becoming known). Still, and while the final image is, like everything else in the game, lovely in its own right, this particular ambiguous ending feels weirdly abrupt. The game has such a flavor of fable or allegory that one somehow wants a little more from it at the end, something to carry away back to real life. But then again, beauty, which Loom possesses in spades, has a value of its own, and it’s uncertain whether the sequels Moriarty originally planned to make — Loom had been envisioned as a trilogy — would have enriched the story of the first game or merely, as so many sequels do, trampled it under their weight.

From the practical standpoint of a prospective purchaser of Loom upon its initial release, on the other hand, there’s room for complaint beyond quibbling about the ending. We’ve had occasion before to observe how the only viable model of commercial game distribution in the 1980s and early 1990s, as $40 boxed products shipped to physical store shelves, had a huge effect on the content of those games. Consumers, reasonably enough, expected a certain amount of play time for their $40. Adventure makers thus learned that they needed to pad out their games with enough puzzles — too often bad but time-consuming ones — to get their play times up into the region of at least twenty hours or so. Moriarty, however, bucked this trend in Loom. Determined to stay true to the spirit of minimalism to the bitter end, he put into the game only what needed to be there. The end result stands out from its peers for its aesthetic maturity, but it’s also a game that will take even the most methodical player no more than four or five hours to play. Today, when digital distribution has made it possible for developers to make games only as long as their designs ask to be and adjust the price accordingly, Loom‘s willingness to do what it came to do and exit the stage without further adieu is another quality that gives it a strikingly modern feel. But in the context of the times of the game’s creation, it was a bit of a problem.

When Loom was released in March of 1990, many hardcore adventure gamers were left nonplussed not only by the game’s short length but also by its simple puzzles and minimalist aesthetic approach in general, so at odds with the aesthetic maximalism that has always defined the games industry as a whole. Computer Gaming World‘s Johnny Wilson, one of the more sophisticated game commentators of the time, did get what Loom was doing, praising its atmosphere of “hope and idealism tainted by realism.” Others, though, didn’t seem quite so sure what to make of an adventure game that so clearly wanted its players to complete it, to the point of including a “practice” mode that would essentially solve all the puzzles for them if they so wished. Likewise, many players just didn’t seem equipped to appreciate Loom‘s lighter, subtler aesthetic touch. Computer Gaming World‘s regular adventure-gaming columnist Scorpia, a traditionalist to the core, said the story “should have been given an epic treatment, not watered down” — a terrible idea if you ask me (if there’s one thing the world of gaming, then or now, doesn’t need, it’s more “epic” stories). “As an adventure game,” she concluded, “it is just too lightweight.” Ken St. Andre, creator of Tunnels & Trolls and co-creator of Wasteland, expressed his unhappiness with the ambiguous ending in Questbusters, the ultimate magazine for the adventuring hardcore:

The story, which begins darkly, ends darkly as well. That’s fine in literature or the movies, and lends a certain artistic integrity to such efforts. In a game, however, it’s neither fair nor right. If I had really been playing Bobbin, not just watching him, I would have done some things differently, which would have netted a different conclusion.

Echoing as they do a similar debate unleashed by the tragic ending of Infocom’s Infidel back in 1983, the persistence of such sentiments must have been depressing for Brian Moriarty and others trying to advance the art of interactive storytelling. St. Andre’s complaint that Loom wouldn’t allow him to “do things differently” — elsewhere in his review he claims that Loom “is not a game” at all — is one that’s been repeated for decades by folks who believe that anything labeled as an interactive story must allow the player complete freedom to approach the plot in her own way and to change its outcome. I belong to the other camp: the camp that believes that letting the player inhabit the role of a character in a relatively fixed overarching narrative can foster engagement and immersion, even in some cases new understanding, by making her feel she is truly walking in someone else’s shoes — something that’s difficult to accomplish in a non-interactive medium.

Responses like those of Scorpia and Ken St. Andre hadn’t gone unanticipated within Lucasfilm Games prior to Loom‘s release. On the contrary, there had been some concern about how Loom would be received. Moriarty had countered by noting that there were far, far more people out there who weren’t hardcore gamers like those two, who weren’t possessed of a set of fixed expectations about what an adventure game should be, and that many of these people might actually be better equipped to appreciate Loom‘s delicate aesthetics than the hardcore crowd. But the problem, the nut nobody would ever quite crack, would always be that of reaching this potential alternate customer base. Non-gamers didn’t read the gaming magazines where they might learn about something like Loom, and even Lucasfilm Games wasn’t in a position to launch a major assault on the alternative forms of media they did peruse.

In the end, Loom wasn’t a flop, and thus didn’t violate Steve Arnold’s dictum of “don’t lose money” — and certainly it didn’t fall afoul of the dictum of “don’t embarrass George.” But it wasn’t a big hit either, and the sequels Moriarty had anticipated for better or for worse never got made. Ron Gilbert’s The Secret of Monkey Island, Lucasfilm’s other adventure game of 1990, was in its own way as brilliant as Moriarty’s game, but was much more traditional in its design and aesthetics, and wound up rather stealing Loom‘s thunder. It would be Monkey Island rather than Loom that would become the template for Lucasfilm’s adventure games going forward. Lucasfilm would largely stick to comedy from here on out, and would never attempt anything quite so outré as Loom again. It would only be in later years that Moriarty’s game would come to be widely recognized as one of Lucasfilm Games’s finest achievements. Such are the frustrations of the creative life.

Having made Loom, Brian Moriarty now had four adventure games on his CV, three of which I consider to be unassailable classics — and, it should be noted, the fourth does have its fans as well. He seemed poised to remain a leading light in his creative field for a long, long time to come. It therefore feels like a minor tragedy that this, his first game for Lucasfilm, would mark the end of his career in adventure games rather than a new beginning; he would never again be credited as the designer of a completed adventure game. We’ll have occasion to dig a little more into the reasons why that should have been the case in a future article, but for now I’ll just note how much an industry full of so many blunt instruments could have used his continuing delicate touch. We can only console ourselves with the knowledge that, should Loom indeed prove to be the last we ever hear from him as an adventure-game designer, it was one hell of a swansong.

(Sources: the book Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; ACE of April 1990; Questbusters of June 1990 and July 1990; Computer Gaming World of April 1990 and July/August 1990. But the bulk of this article was drawn from Brian Moriarty’s own Loom postmortem for, appropriately enough, the 2015 Game Developers Conference, which was a far more elaborate affair than the 1988 edition.

Loom is available for purchase from GOG.com. Sadly, however, this is the VGA/CD-ROM re-release — I actually prefer the starker appearance of the original EGA graphics — and lacks the scene-setting audio drama. It’s also afflicted with terrible voice acting which completely spoils the atmosphere, and the text is bowdlerized to boot. Motivated readers should be able to find both the original version and the audio drama elsewhere on the Internet without too many problems. I do recommend that you seek them out, perhaps after purchasing a legitimate copy to fulfill your ethical obligation, but I can’t take the risk of hosting them here.)

Bobby Tuck

February 18, 2017 at 2:41 am

great article!

Loom reminds me — have you ever done an article on ‘Myth’? I vaguely remember the game — I think it was Bungie (after ‘Marathon’) — a bunch of soldiers on a battlefield, running down hills. I think I had it on my first Windows machine (after my Mac SE college days) that had a ‘voodoo’ graphics card.

Anyway, I remember getting ‘Myth’ at Best Buy and thinking, yeah, Bungie is pretty cool. Marathon, of course, was awesome — long before ‘Halo’ — and pretty much only for Mac folks. But Myth — Myth was interesting because it was … well, weird. And not very enjoyable. But it was Bungie. And Bungie — at the time — was all about Macs and Marathon. And Marathon — wow — that was fantastic. Even better, I daresay, than Doom.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 2:49 am

That’s years away yet in the chronology, but I can give you a strong maybe someday. ;)

Jrod

March 2, 2018 at 8:05 pm

Oh man… thank you so much for reminding me of Myth. I absolutely loved and adored that game. I am bummed you didn’t find it enjoyable, because for me it was one of the most enjoyable and compelling of all time!

Michael Russo

February 18, 2017 at 2:56 am

Haven’t read the article yet but very excited to see an article on Loom! This game and Myst I used to introduce a few ‘senior’ relatives to adventure games on their first computers, and they loved them.

Also, why are you always visiting Rochester in the winter? It’s cold and there’s a lot of snow! Maybe some cool winter carnivals there or nearby though (I think Saranac Lake is having one this weekend). Have a garbage plate while you’re there!

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 6:02 am

It’s just worked out that way as far as timing. Maybe next time I can come out in the summer. As it is, though, I don’t really mind holing up in a cozy hotel room. Gives me a chance to play some games… err, do research.

Benjamin Vigeant

February 18, 2017 at 4:56 am

On some early birthday I received a Lucasarts collection with Monkey Island, Indiana Jones, Maniac Mansion, Zak McCracken, and Loom. Loom continues to haunt me to this day, much in the same way that Wishbringer does (and I didn’t even know they were done by the same fellow!)

I appreciate how gosh darn inventive and *weird* Loom is. It just feels like you’re getting a tiny slice of an enormous hidden world of strange tragedy. The Book of Patterns and the audio drama (which the collection didn’t include) definitely help this.

Jimmy, thanks for giving me another occasion to think of a long favorite game, and Brian if you read this I’ll toss bucks towards a kickstarter.

Sniffnoy

February 18, 2017 at 5:19 am

This is irrelevant nitpicking, but I’d say E3 is probably the “biggest, glitziest event” in the computer game industry, rather than the Game Developers’ Conference.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 6:06 am

True. Edit made.

Alex Smith

February 18, 2017 at 6:43 am

One small correction: Zak McKracken was a David Fox game, not a Noah Falstein game.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 1:32 pm

Thanks!

Yeechang Lee

February 18, 2017 at 7:22 am

Jimmy, based on this and other recent entries (and, really, the entire blog), I presume/expect that you will be covering Adam Cadre’s Photopia as another example of how a game doesn’t need to allow complete freedom to succeed as a narrative?

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 1:38 pm

Yes, that one’s unavoidable. Again, though, it’s years in the future, in both blog years and historical years.

Jubal

February 18, 2017 at 10:29 am

With comments like St. Andre’s “If I had really been playing Bobbin, not just watching him, I would have done some things differently, which would have netted a different conclusion”, I really have to wonder what people were expecting – games with complex, branching plots were not exactly common back then.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 1:43 pm

A CRPG like Wasteland did offer, if not complete freedom, certainly a lot more flexibility and possibly even multiple endings (can’t remember at the moment). It did this, of course, at the expense of a much less developed plot, whatever path you took.

But yeah, there’s a certain element to his comments of criticizing an adventure game for being an adventure game, even if Loom was an unusually linear specimen of the breed. Complaining that Loom won’t let you, say, join with the villain and rule over Chaos strikes me as a fundamental misunderstanding of what it’s trying to do and be. If that’s not for you, fine, but criticizing it on that basis is a bit like a film critic criticizing a romantic comedy for not being an action movie.

It’s to avoid this syndrome that when I play games for this blog that I know are at their core just not for me, like SimCity or Prince of Persia, I try to explain that reality rather than hammer away at the game as if *other* non-competitive building games or platformers delight me.

Jonathan Badger

February 18, 2017 at 2:00 pm

While taste is subjective, and I haven’t played Loom for some years, I’m surprised at the characterization of the voice acting on the CD-ROM as “terrible”. As I recall, it was one of the first games with voice acting by professional actors (many of whom were the same as in the audio drama) — far better than in other games of the same era which seemed to simply use the voices of the programmers and their families.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 2:46 pm

Maybe it’s just that it clashes with the game’s minimalist aesthetics rather than being intrinsically bad in itself. All I know is that I like it not.

whomever

February 18, 2017 at 3:05 pm

I actually enjoyed Loom quite a bit, but never bothered listening to the CD-Rom. I will agree that voice-acting wise, games of that era weren’t exactly the Royal Shakespeare Company. Saddest was Wing Commander 3, which got Mark Hamill-but he was so lousy it was pathetic.

Ignacio

February 18, 2017 at 5:51 pm

Another great article, Mr. Maher!

A small correction: the designers of ‘Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure’ were Ron Gilbert, Noah Falstein AND David Fox.

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 8:16 pm

Keep trying to flush him down the Memory Hole, but you people keep spitting him back out at me. Anyway, thanks!

Alex Smith

February 18, 2017 at 6:58 pm

You know, between this and crediting Falstein instead of Fox for Zak McCracken, I am beginning to wonder why Jimmy seems intent on trying to erase poor Mr. Fox from history! =p

Nate

February 18, 2017 at 7:12 pm

Interesting, never played this but saw the ads when it came out. Another one to play for the first time in my retirement days. :-)

You need commas for an appositive phrase: “minor tragedy that this his first game for Lucasfilm would mark” -> “minor tragedy that this, his first game for Lucasfilm, would mark”

http://www.chompchomp.com/terms/appositive.htm

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 8:17 pm

Thanks!

Johannes Paulsen

February 18, 2017 at 9:05 pm

I never played Loom, because it was released during that dead zone of computer gaming when I was young and poor, and did not have the latest hardware. It wasn’t until I started becoming more interested in game design that I started gathering that it was considered a bit of a classic. The clip in this article was the first real exposure I had to it.

That said…am I the only one who thinks the Tchaikovsky score completely overwhelms the game? It doesn’t flow with what was happening on the screen at all. I was even more surprised to see that the game is supposed to “start darkly” because, man, that score doesn’t give off a dark mood in the slightest. Maybe a little Mussorgsky would’ve worked better, if you needed something in the public domain….

Perhaps this was a case of the designer including the music he loved instead of what was right for the scene?

Jimmy Maher

February 18, 2017 at 10:09 pm

I think it suits the mood perfectly, myself. But then it was Ken St. Andre who said the game “starts darkly.” That’s not the word I would use at all. Wistful, melancholic, sure — Tchaikovsky’s music has been described as “a smile through tears” — but not just “dark.”

LoneCleric

February 22, 2017 at 5:29 pm

I have to chime in here and say that the soundtrack always felt _just right_ as I played the game on my Amiga. In fact, that MT-32 clip you used is positively dreadful as far I’m concerned – the “Swan Theme” doesn’t fit there at all!

Compare to this Amiga intro: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ydTri3JWvM

The Swan Theme didn’t appear until much later in my playthrough, at a point where its usage felt right.

Johannes Paulsen

March 3, 2017 at 4:50 pm

@ Jimmy & LoneCleric: Fair points. Perhaps I’ll have to play it.

Petter Sjölund

February 19, 2017 at 8:51 am

Many prefer the FM Towns version of Loom, which has 256-color graphics and digital orchestral music but no voice acting, and retains all of the original text.

https://youtu.be/JjTVyrtFax4

Naomi

February 19, 2017 at 10:09 am

Oh man I loved playing Loom when i was little. That bit at the end when the sky cracks open blew my mind. Looking back, I think Loom started me down the road to sci-fi. And the theme music and the loom rippling… I can still remember the notes even now. Pretty heady stuff for an 8 year old.

Doug Orleans

February 19, 2017 at 12:32 pm

Surprised no one caught this yet: “without further adieu” should be “without further ado”.

Jimmy Maher

February 19, 2017 at 6:04 pm

That was actually an intentional play on words. ;)

Doug Orleans

February 19, 2017 at 7:08 pm

Ah, sorry, that went right over my head… It’s a pretty common mistake so I wasn’t thinking of it as a pun. I apologize for much adieu about nothing!

Lisa H.

February 23, 2017 at 8:24 pm

I thought the same as Doug, so perhaps it’s a bit oblique…

Hresna

March 6, 2025 at 12:40 pm

Fwiw, I was with you Jimmy – saw the malapropism and then noticed what you did there.

MCP

February 19, 2017 at 10:27 pm

Nice article Jimmy!

“(..)expect that you’re collecting musical drafts” – maybe “except” ?

One way to play closer to the EGA version could be to play the Amiga or even Atari ST versions, which came out a few months after PC and should be uncensored and equally based on a 16 colour palette. Music was not as good as Roland, though: being Amiga a renown sound/music powerhouse at the time, this probably hints Lucasgames did not go the extra mile in doing the port.

“(Zak Mc Kraken) While successful enough in its day, it never garnered the love that’s still accorded to Maniac Mansion today.”

Well, on the whole this is true, and Day of the Tentacle added a lot to that success in my opinion; but I remember Zak being really *huge* in Germany, Italy and UK at the times – more than Maniac Mansion ever was, with magazines talking for months about it and people using nicknames such as “Sushi in the fishball” in bulletin board systems, pre-internet era. The nose-and-moustache avatar is still popular today. I don’t have sales numbers to support this, but maybe a case of different commercial destiny and/or perception from this side of the Atlantic?

Jimmy Maher

February 20, 2017 at 11:43 pm

Thanks!

I do think the games’ contemporary reputations have Maniac Mansion way out in front, but what you say may very well have been correct back in the day.

Alex Smith

February 21, 2017 at 3:00 pm

I think its still rather huge in Germany, which really fell hard for the game for some reason. Certainly in the rest of the world it does not get the same level of attention.

Ricky Derocher

February 21, 2017 at 10:00 pm

Zak is pretty popular with the C64 retro crowd. Of course Zak was developed for the C64 first, and Zak is quite an impressive technical feat for the C64! The C64 never got any of the later SCUMM games past Zak.

GeoX

February 20, 2017 at 10:07 am

Aw…I liked The Last Crusade. No doubt there’s a lot of nostalgia talking here, but I really thought it did a good job of converting the plot of the movie to something more meaningfully interactive. Fate of Atlantis is better, of course.

Ruber Eaglenest

February 20, 2017 at 5:13 pm

Beautiful but sad article.

I’m quite a fan of Brian Moriarty, and I always lamented why he never returned to design games… because… well, those of him are the BEST ever. So really interested to see when that “conclusion” comes.

Thanks!

Jason Dyer

February 20, 2017 at 6:05 pm

I’m going to have to disagree with you here:

The game dutifully walks you through the plot you’ve already watched unfold on the silver screen, without ever taking flight as a creative work in its own right.

There is a *lot* of branching. There is so much branching I actually have a hard time thinking of a “classic-style” adventure game with more branching. (Fate of Atlantis, which is admittedly a better game, does a big branch into 3 routes at the beginning, but doesn’t really have any plot-driven branches in the middle.)

For example, you can play the scene entering the castle exactly like the movie (Indy punching the butler out) but it is quite possible to talk your way in. If you do so, it makes other things either.

If you recall the scene where they get the grail book from Berlin: it’s possible to not even lose the book and be able to skip the Berlin scene entirely.

There are quite a few endings as well; things don’t have to go anything like the movie.

Jimmy Maher

February 20, 2017 at 11:41 pm

Hmm… maybe I just tried to do what Indy did in the movie, found it generally worked, and didn’t explore further. This in itself is of course another problematic aspect of adapting a linear story to an adventure game, but it seems I may have underestimated the game’s flexibility.

Don Alsafi

March 11, 2017 at 11:42 pm

You definitely did underestimate the game’s flexibility! For instance, what happens after you escape from Castle Brunwald can go in several different directions.

– If the Grail Diary is stolen from at the Castle, you’ll detour to Berlin to get it back (like in the movie). On the other hand, if you’re clever enough to hand over Indy’s childhood facsimile when they ask for the Diary, you keep the real diary and thus avoid the detour to Berlin. (It’s also possible, though much harder, to free Henry and escape the castle without ever getting captured.)

– Once you get to the airport, you can steal a biplane (if you had previously found the book on how to fly a biplane in the Venice library), or else finagle some way onto the blimp (buy or steal tickets, or fight your way on board). You can then progress through this section in a couple of different ways, which ends in fighting through the bowels of the blimp and stealing a biplane there.

– When your biplane eventually crashes on the ground, you’ll then steal a motorcycle and have to bribe, fight or talk your way through as many as seven different roadblock checkpoints out of Germany. Here’s a neat twist though: the longer you’re in the air – either on the blimp (if you found a way to delay them turning back), and/or by how many enemy planes you manage to gun down in the biplane (thus keeping you from getting shot down for that much longer) – adds up to the more checkpoints you bypass along the road! Supposedly if you’re enough of a sharp shooter to take out all 16 enemy planes, you can fly the entire way out of Germany, and thus avoid the roadblocks altogether.

So it kind of sounds like you let your knowledge of the movie’s narrative direct you toward the most straightforward solutions – and then were frustrated that it seemed such a boring and uncreative adaptation! When honestly it couldn’t be further from the truth. After all, one of the common complaints you hear about adventure games is people responding to their “authored” nature; that there’s usually only ONE path through the game, and that other solutions they come up with which should work, don’t – simply because that’s not The One Correct Answer which the designer came up with. (Think of the Sierra adventures.) As it happens, I’m hard-pressed to think of another game that does a better job of not only offering various paths throughout the game, but offering multiple solutions to the same puzzle, at almost every step of the way.

Last thought: Critics of the genre also often complain that there’s no replayability; once you solve every puzzle and get to the end of the story, there’s nothing more to do. This game, on the other hand, is one I recall playing again and again and again, astonished at all the different paths, solutions and combinations to be found. (Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis would take this replayability element in a direction more akin to the Quest for Glory games; early on, you get to declare whether you prefer fighting, talking, or puzzles, and the rest of the game deploys that style accordingly.)

Don Alsafi

March 11, 2017 at 11:50 pm

This ridiculously detailed post explaining the highest score you can theoretically get from one playthrough, does a good, quick job of giving a glimpse at just how many different ways there are to do things throughout the game. (Since the exercise necessary involves seeing how many of the multiple solutions could be deployed at the same time.)

Dan

February 20, 2017 at 6:21 pm

I played the EGA version of Loom as a child (as part of the Classic Adventures collection, so no audio drama), and didn’t discover the existence of the CD version until many years later. I didn’t think the voice acting was bad, although some of the characters sounded very different from what I had imagined, but I can’t get past the edited text.

I’ve heard several explanations for why so many changes were made: insufficient space on the CD-ROM; the dialogue didn’t sound good when spoken aloud; etc. I’ve even heard that Orson Scott Card had a hand in the edited version. Do you have any insight?

Jimmy Maher

February 20, 2017 at 11:37 pm

No, but I’ve never really looked into it either. Maybe a bit later…

himitsu

February 20, 2017 at 6:53 pm

“Simplicity, however, wasn’t exactly trending in the computer-games industry of 1988.” – I really cannot agree with that paragraph.

My argument follows:

– Wargames were always niche genre. To my best knowledge they sold at least an order of magnitude less well than RPGs or adventures, and especially arcade games of the era. So this genre is unfit for comparison.

– SSI and SSG were still using the old engines they developed ages before for the 8-bit micros. In comparison to that, EA’s Lords Of Conquest, or the legendary Empire or The Ancient Art of War were very simple games to play.Balance of Power had complex mechanics but a very intuitive menu driven gameplay.

– Many of the best sellers were very simple games: Marble Madness, Skate or Die, Test Drive, California Games, International Karate, Uridium, Pirates, The Last Ninja, Barbarian, Armalyte, Leaderboard, Hardball just to mention a few.

– Even hardcore audiences were growing. Flight Simulator II was a system seller for the IBM PC. Gunship and Falcon showed to people that computer games aren’t for kids only. Bard’s Tale made Wizardry digestible to the public, while Ultima innovated in big leaps.

– the 86-88 period was the leap when presentation and detail improved enough that gaming was not only for the computer enthusiasts. Leaderboard, Test Drive or Falcon did not have the same nerd connotation as any Wizardry, or any SSI game.

– Interestingly, in my opinion, Computer Gaming World gives a very distinct look at the computer game market of the 80s because it was established by grognards and targeting enthusiasts for the first 7-8 years of its publication. In contrast to that, Computer+Video Games was targeting a younger audience and it reviewed completely different games at the same time.(different markets is the other reason of course) Computer Gaming World often showed action games in the Taking-a-Peek section but rarely reviewed them, but almost all SSI and SSG title got multiple page reviews. For similar reason they stick to the Apple II for an awfully lot of time.

Jimmy Maher

February 20, 2017 at 11:33 pm

What with Lucasfilm Games being an American company, that statement was rather focused on the American market. Note also that it relates to computer games, not console games. Tellingly, Computer and Video Games was a British publication, not even available in North America. Games did admittedly evolve somewhat differently in Europe, largely thanks to the absence there of Nintendo.

By 1988, simpler forms of games in North America were for the most part — there are of course always exceptions — migrating rapidly from the Commodore 64 to the Nintendo, leaving the PC the domain of the very strategy games, CRPGs, and adventures you mention. And while you’re certainly correct that a series like Ultima advanced by leaps and bounds, I don’t think we can say those games got simpler to play. At least through Ultima V, the Ultima series got significantly more complicated to play with every iteration.

And while I agree that the arrival of a new generation of machines by 1986 *should* have made gaming more popular, it never actually created the growth spurt North American game publishers had expected. Believe me, this failure was a source of constant frustration for everyone. Annual growth of the North American computer-game industry remained in the single digits from 1986 to the early 1990s, with a brief shrinkage in 1989 thanks to Nintendo annihilating the old Commodore 64 market. This explains why so many traditional computer-game makers, like Electronic Arts and Interplay, suddenly jumped into the Nintendo market, which went from nothing in 1986 to dwarfing computer games in 1989. Computer games wouldn’t see a big growth spurt of their own until the “multimedia PC” boom and, soon after, the arrival of the World Wide Web created a second Home Computer Revolution in North America, this one much more lasting than the first.

Also, Doom. ;)

Ibrahim Gucukoglu

February 20, 2017 at 7:32 pm

I managed to get hold of a copy of the original cassette and diskette set of Loom, though I believe it’s available on CD now and probably electronicly through GOG, however I always loved the audio drama. OK, the production and sound design values of that 30 minute set piece were obviously very minimal, however it just sounded so fairy tale like it just captured me and took me along with the story. The musical score as you rightly say is a masterpiece in its own right and although I never got to experience it on an actual Roland MT32 synth, the CD version I played has this as well as a complete audio script for all the characters not to mention the soundtrack, remastered and sounding better than ever. Thanks as always for the trip down memory lane.

Anthony Noel

February 21, 2017 at 10:38 am

Wasn’t Brian also involved with the design and writing on Lucasart’s The Dig?

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2017 at 10:46 am

Yes, but I believe that very little of his work showed up in the finished product.

Lee Jones

February 21, 2017 at 7:35 pm

As I recall, Moriarty was, at the very least, rather instrumental in the eventual change of focus in the plot of “The Dig”.

The original idea was something closer to an action rpg, but Moriarty excised the rpg elements, and made the story darker.

Steven Marsh

February 22, 2017 at 2:08 am

This essay has stuck with me for a few days… not unlike Loom itself, really…

A couple of random thoughts:

• You tangentially raise a great question about what is considered the “real” version of a game. I first played Loom on an IBM PC emulator card for my Apple IIgs; the card was only capable of four-color CGA, so that’s how I played Loom. I recognized at the time that it was a pale imitation of the “real” experience, but I was happy to just get to play it in any form (since the LucasArts games weren’t getting ported to the Apple). I didn’t play Loom again until I got my first CD-ROM drive, when (IIRC) the CD-ROM version came bundled with the system. So the EGA version was never on my radar; even now, firing it up via ScummVM, it just feels . . . off.

This is a microcosm example of an issue of games from this era, where it’s tough to tell which version of a game is the definitive one. Unlike movies or books, which are often presented and presentable in a form that’s obviously really close to the creators’ intent, games are more at the mercy of the systems they run on. I know many classic games I’ve spent hours tweaking with audio drivers, graphic sets, etc., trying to divine what the creators “really” wanted us to experience, but in many cases it’s impossible to know.

• Having read this essay, I tried playing Loom again. My time is tight at the moment, so — only a few screens in — I found myself yelling at the screen, “WALK QUICKER.” I know the pace is somewhat part of the experience, but another thing that’s challenging about considering computer games as an art form is that it’s difficult to engage in “random access.” With a book I can flip to a chapter or passage that strikes my fancy. (With a digital version, I can even search for it.) In the DVD/Blu-Ray/digital/YouTube era, pulling up beloved moments in a film or TV show is trivial. But a game is usually at the mercy of being played, so it’s usually difficult to impossible to jump to an interesting scene — especially graphic-adventure games of this era. (In comparison, I was curious about an aspect of the endgame of Trinity, so I blazed through the entire game with a walkthrough in less than 30 minutes.)

• The website Extra Credits has done an episode on the topic, but I’ve always been deeply appreciative about games that do what they need to do in a reasonable amount of time, and then end. Loom wouldn’t have been a better game if it had been twice as long or included a half-dozen aimless fetch-quest puzzles to pad out the time. There are many games I’ve played where I would have enjoyed myself twice as much if it had been half as long, and it’s sad that it’s so difficult to monetize and reward creators whose games are nothing but “the good stuff.” (I’ve probably replayed Loom more in my life than most of the Monkey Island games, because I knew I could usually finish it before I got bored.)

Anyway, great essay, as ever. Thanks for your efforts.

Lisa H.

February 22, 2017 at 2:30 am

I loved Loom then and I still do. It’s a shame the trilogy never came to be. (I’ve looked at the fan-made demo for “Forge” and it seems like it could be interesting, although I had a hell of a time with its equivalent to Loom’s drafts system, but I don’t know if that ever got beyond a demo.)

Add me to the list of people who think describing the voice acting as “terrible” is a bit strong; cheesy, perhaps.

Carlton Little

February 23, 2017 at 7:38 pm

You know, you seem like a decent fantasy writer… you might want to try working on a fan-made “Loom” sequel yourself! Just a friendly suggestion, anyhow

Lisa H.

February 23, 2017 at 8:26 pm

Did you mean that reply to go to me, or to Jimmy? I’m not a fantasy writer… (not to mention not a programmer!)

Carlton Little

February 25, 2017 at 7:24 pm

Actually, I meant thou–Lisa H. Been following this blog for a long time and I visited your site before. As I recall, it was fecund with creative endeavors.

So you could try your hand at Doom 2.. er, Loom 2. :-)

Lisa H.

February 26, 2017 at 5:33 am

Oookay… I still really have no idea what you’re talking about. On my website is some poetry which is mostly not that good, and then my game walkthroughs. That’s it. (I’ve also written some Harry Potter fanfic posted elsewhere, but it’s been like five or six years since I could do any of that.)

Lisa H.

February 23, 2017 at 8:27 pm

Also: it was one hell of a swansong I see what you did there. ;)

Now that I’ve had the chance to listen to the videos for the MT-32 and Amiga openings, I wonder if this is one of those games where whatever one first played it as seems (subjectively) to be definitive? Because to me those both sound kind of “meh” or wrong, which I guess means that for me it’s the AdLib or Soundblaster that would sound the best!

Pedro Timóteo

February 24, 2017 at 9:33 pm

Probably. Don’t worry, you’re not the only one; I remember seeing people in the DOSBox forums who said that anything other than PC speaker sound (at least in some particular games) sounded “wrong” to them, because of course that’s how they played those games back in the day… :)

Me, I’m the opposite; while on one hand I love comparing different versions (“let’s see what Monkey Island 1 sounds like with a CMS Gameblaster card. Now let’s see what Ultima 6 sounds like with an Innovation card. Or Pool of Radiance with Tandy sound effects. Or…”), one of the best moments of my gaming life was trying out some of my favorite games with my just-bought original Sound Blaster (even though at the time that mostly meant Adlib music; games using the SB’s digital sounds for music would still take a few years to appear). Even better was years later buying a Roland SCC-1 and doing it all over again (and hearing instruments sounding like actual instruments for the first time).

Rowan Lipkovits

February 24, 2017 at 7:44 pm

“We’ll have occasion to dig a little more ”

Zing!

iPadCary

June 8, 2017 at 4:12 am

In my Top 5 boxcovers ….

I wish whoever owns the rights would bring this to iOS.

Other Golden Age games have met with fantastic success.

Jason

February 11, 2021 at 10:22 am

Are you ever going to explore a bit further into why Brian Moriarty left the game industry? Loom was really a beautiful game, and I’ve always been curious as to why it ended up being his last.

Jimmy Maher

February 11, 2021 at 10:28 am

He didn’t actually leave the industry; he just transitioned into other roles. But I agree that the loss of his voice as a writer and designer was greatly to gaming’s detriment. There may be room to explore some of what happened in my article on The Dig. (Brian Mortiary was the first lead designer on that infamously troubled, oft-delayed project.)