The adventure makers at LucasArts had a banner 1993. One of the two games they released that year, Day of the Tentacle, was the veritable Platonic ideal of a cartoon-comedy graphic adventure; the other, Sam and Max Hit the Road, was merely very, very good.

Following a quiet 1994 on the adventure front, LucasArts came roaring back in the spring of 1995 with Full Throttle, a game that seemed to have everything going for it: it was helmed by Tim Schafer, one of the two lead designers from Day of the Tentacle, and boasted many familiar names on the art and sound front as well. Yet it wasn’t just a retread of what had come before. This interactive biker movie had a personality very much its own. Many soon added it to the ranks of LucasArts’s most hallowed classics.

Sadly, though, I’m not one of these people…

It’s easy — perhaps a bit too easy — to read LucasArts’s first post-DOOM adventure game as a sign of the changes that id Software’s shareware shooter wrought on the industry after its debut in December of 1993. Action and attitude were increasingly in, complexity and cerebration more and more out. One can sense throughout Full Throttle its makers’ restlessness with the traditional adventure form — their impatience with convoluted puzzles, bulging inventories, and all of the other adventure staples. They just want to have some loud, brash fun. What other approach could they possibly bring to a game about outlaw motorcycle gangs?

The new attitude is initially bracing. Consider: after a rollicking credits sequence that plays out behind over-driven, grungy rock and roll, you gain control of your biker avatar outside a locked bar. Your first significant task is to get inside the bar. Experimenting with the controls, you discover that you have just three verb icons at your disposal: a skull (which encompasses eyes for seeing and a mouth for talking), a raised fist, and a leather boot. Nevertheless, the overly adventure-indoctrinated among you may well spend quite some time trying to be clever before you realize that the solution to this first “puzzle” is simply to kick the door in. Full Throttle is a balm for anyone who’s ever seethed with frustration at being told by an adventure game that “violence isn’t the answer to this one.” In this game, violence — flagrant, simple-minded, completely non-proportional violence — very often is the answer.

But let’s review the full premise of the game before we go further. Full Throttle takes place in the deserts of the American Southwest during a vaguely dystopian future — albeit not, Tim Schafer has always been at pains to insist, a post-apocalyptic one. You play Ben, a stoic tough guy of few words in the Clint Eastwood mold, the leader of a biker gang who call themselves the Polecats. “The reason bikers leaped out at me is that they have a whole world associated with them,” said Schafer in a contemporary interview, “but it’s not a commonplace environment. It’s a fantastic, bizarre, wild, larger-than-life environment.” And indeed, everything and everyone in this game are nothing if not larger than life.

The plot hinges on Corley Motors, the last manufacturer of real motorcycles in the country — for the moment, anyway: a scheming vice president named Adrian Ripburger is plotting to seize control of the company from old Malcolm Corley and start making minivans instead. When the Polecats get drawn into Ripburger’s web, Ben has to find a way to stop him in order to save his gang, his favorite model of motorcycle, and the free-wheeling lifestyle he loves. The story plays out as a series of boisterous set-pieces, a (somewhat) interactive Mad Max mixed with liberal lashings of The Wild One. Although I’m the farthest thing from a member of the cult of Harley Davidson — I’m one of those tree huggers who wonders why it’s even legal to noise-pollute like some of those things do — I can recognize and enjoy a well-done pastiche when I see one, and Full Throttle definitely qualifies.

Certainly none of this game’s faults are failures of presentation. As one might expect of the gaming subsidiary of Lucasfilm, LucasArts’s audiovisual people were among the best in the industry. They demonstrated repeatedly that the label “cartoon-comedy graphic adventure” could encompass a broader spectrum of aesthetics than one might first assume. While Day of the Tentacle was inspired by the classic Looney Tunes shorts, and Sam and Max Hit the Road by the underground comic books of the 1980s, Full Throttle‘s inspirations were the post-Watchmen world of graphic novels and trendy television: the game’s hyperactive jump cuts, oblique camera angles, and muddy color palette were all the rage on the MTV of Generation Grunge.

In fact, Schafer tried to convince Soundgarden, one of the biggest rock bands of the time, to let him use their music for the soundtrack — only to be rejected when their record company realized that “we weren’t going to give them any money” for the privilege, as he wryly puts it. Instead he recruited a San Francisco band known as the Gone Jackals, who were capable of a reasonable facsimile of Soundgarden’s style, to write and perform several original songs for the game. Bone to Pick, their 1995 album which included the Full Throttle tracks, would sell several hundred thousand copies in its own right on the back of the game’s success. All of this marked a significant moment in the mainstreaming of games, a demonstration that they were no longer siloed off in their own nerdy pop-culture ghetto but were becoming a part of the broader media landscape. The days when big pop-music acts would lobby ferociously to have their work selected for a big game’s in-world radio station were not that far away.

The Gone Jackals. Like so many rock bands who haven’t quite made it, they always seem to be trying just a bit too hard in their photographs…

Full Throttle‘s writing too has all the energy and personality one could ask for. If the humor is a bit broad and obvious, that’s only appropriate; Biker Ben is not exactly the subtle type. The voice acting and audio production in general are superb, as was the norm for LucasArts thanks to their connections to Hollywood and Skywalker Sound. Particular props must go to a little-known character actor named Roy Conrad, who delivers Ben’s lines in a perfect gravelly deadpan, and to Mark Hamill of Star Wars fame, who, twelve years removed from his last gig as Luke Skywalker, was enjoying a modest career renaissance in cartoons and an ever-increasing number of videogames. He shows why he was so in-demand as a voice actor here, tearing into the role of the villain Ripburger with a relish that belies his oft-wooden performances as an actor in front of cameras.

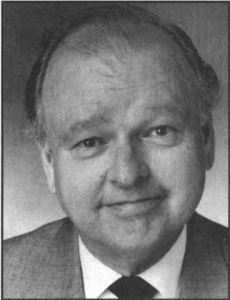

The sweetest story connected with Full Throttle is that of Roy Conrad, a mild-mannered advertising executive who decided to reconnect with his boyhood dream of becoming an actor at age 45 in 1985, and went on to secure bit parts in various television shows and movies. As you can see, he looked nothing like a leader of a motorcycle gang, but his voice was so perfect for the role of Ben that LucasArts knew they’d found their man as soon as they heard his audition tape. Conrad died in 2002.

But for all its considerable strengths, Full Throttle pales in comparison to the LucasArts games that came immediately before it. It serves as a demonstration that presentation can only get you so far in a game — that a game is meant to be played, not watched. And alas, actually playing Full Throttle is too often not much fun at all.

The heart of Full Throttle‘s problem is a mismatch between the type of game it wants to be and the type of game its technology allows it to be. To be sure, LucasArts tried mightily to adapt said technology to Tim Schafer’s rambunctious rock-and-roll vision. They grafted onto SCUMM (“Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion“), their usual adventure-game engine, a second, action-oriented engine called INSANE (“INteractive Streaming ANimation Engine”), which had been developed for 1993’s Star Wars: Rebel Assault, a 3D vehicular rail shooter. This allowed them to interrupt the staid walking-around-talking-and-solving-puzzles parts of Full Throttle with blasts of pure action. “We didn’t think it would fly if we told players they were a bad-ass biker,” says LucasArts animator Larry Ahern, “and then made them sit back and watch every time Ben did a cool motorcycle stunt, and then gave them back the cursor when it was time for him to run errands. With Full Throttle, I think the combination [of action and traditional adventure elements] made a lot of sense, but I think the implementation just didn’t live up to the idea.”

It most definitely did not: the action mini-games range from tedious to excruciating. Schafer elected to partially reverse LucasArts’s longstanding “no deaths and no dead ends” policy, sacrosanct since 1990’s The Secret of Monkey Island, by allowing the former if not the latter in Full Throttle. This decision was perhaps defensible in light of the experience he was hoping to create, but boy, can it get exhausting in practice. The second-to-worst mini-game is an interminable sequence inspired by the 1991 console hit Road Rash, in which you’re riding on your motorcycle trying to take out other bikers by using exactly the right weapon on each of them, wielded with perfect timing. Failure on either count results in having to start all over from the beginning. To be fair, the mini-game looks and sounds great, with electric guitars squealing in the background and your chopper’s straight pipes throbbing under you like a 21-gun salute every few seconds. It’s just no fun to play.

LucasArts sound man Clint Bajakian captures the sound of a straight-piped Harley. Full Throttle was the first LucasArts game, and one of the first in general, to have an “all-digital” soundtrack: i.e., all of the sound in the game, including all of the music, was sampled from the real world rather than being synthesized on the computer. This was another significant moment in the evolution of computer games.

The very worst of the action mini-games, on the other hand, is a rare moment where even Full Throttle‘s aesthetics fail it. Near the end of the game, you find yourself in a demolition derby that for my money is the worst single thing ever to appear in any LucasArts adventure. The controls, which are apparently meant to simulate slipping and sliding in the mud of a fairground arena, are indeed impossible to come to grips with. Worse, you have no idea what you’re even trying to accomplish. The whole thing is an elaborate exercise in reading the designers’ mind to set up an ultra-specific, ultra-unlikely chain of happenstance. I shudder to think how long one would have to wrestle with this thing to stumble onto the correct ordering of events. (Personally, I used a walkthrough — and it still took me quite some time even once I knew what I was trying to do.) Most bizarrely of all, the mini-game looks like a game from five or eight years prior to this one, as if someone pulled an old demo down off the shelf and just threw it on the CD. It’s a failure on every level.

The demolition derby, also known as The Worst LucasArts Thing Ever. No, really: it’s incomprehensibly, flabbergastingly bad.

All told, the action mini-games manage to accomplish the exact opposite of what they were intended to do: instead of speeding the story along and making it that much more exciting, they kill its momentum dead.

What, then, of the more traditional adventure-game sections threaded between the action mini-games and the many lengthy cut-scenes? Therein lies a somewhat more complicated tale.

Some parts of Full Throttle are competently, even cleverly designed. The afore-described opening sequence, for example, is a textbook lesson in conveying theme and expectation to the player through interactivity. It teaches her that any convoluted solutions she might conceive to the dilemmas she encounters are not likely to be the correct ones, and that this will be an unusually two-fisted style of adventure game, admitting of possibilities that its more cerebral cousins would never even consider. The first extended adventure section in the game sends you into a dead-ender town in search of a welding torch, a set of handlebars, and some gasoline, all of which you need to get your damaged bike back on the road after Ripburger’s goons have sabotaged it. The game literally tells you that you need these things and waits for you to go out and find them; it doesn’t attempt to be any trickier than that. And this is fine, being thoroughly in keeping with its ethos.

But threaded among the straightforward puzzles are a smattering that fail to live up to LucasArts’s hard-won reputation for always giving their players a fair shake. At one point in that first town, you have to trigger an event, then run and hide behind a piece of scenery. But said scenery isn’t implemented as an object that might bring it to your attention, and it’s very difficult to discover that you can walk behind it at all. In some adventure games, the ones that promise to challenge you at every turn and make you poke around to discover every single possibility, this puzzle might fit the design brief. Here, however, it’s so at odds with the rest of the game that it strikes me more as a design oversight than a product of even a mistaken design intent. Such niggles continue to crop up as you play further, and continue to pull you out of the fiction. One particularly infamous “puzzle” demands that Ben kick a wall over and over at random to discover the one tiny spot that makes something happen.

Do you see that thing shaped a bit like a gravestone just where the streetlight is pointing? It turns out you can walk behind that. Crazy world, isn’t it?

As time goes on, Full Throttle comes to rely more and more on one of my least favorite kinds of adventure puzzles: the pseudo-action sequence, where the designer has a series of death-defying action-movie events, improvisations, and coincidences in mind, and you have to muddle your way through by figuring just how he wants his bravura scene to play out. In other words, you have to fail again and again, using your failures as a way to slowly deduce what the designer has in mind. Fail-until-you-succeed gameplay can feel rewarding in some circumstances, but not when it’s just an exercise in methodically trying absolutely everything until something works, as it tends to be here. The final scene of the game, involving a gigantic cargo plane teetering on the edge of a cliff with a staggering quantity of explosives inside, becomes the worst of all of them by adding tricky timing to the equation.

It’s in places like this one that the mismatch between the available technology and the desired experience really comes to the fore. In a free-roaming 3D engine with the possibility of emergent behavior, the finale could be every bit as rousing as Schafer intended it to be. But in a point-and-click adventure engine whose world simulation goes little deeper than the contents of your inventory… not so much. Executing, say, a death-defying leap out of the teetering plane’s cargo hold on your motorcycle rather loses its thrill when said leap is the only thing the designer has planned for you to do — the only thing you’re allowed to do other than getting yourself killed. The leap in question is the designer’s exciting last-minute gambit, not yours; you’re just the stooge bumbling and stumbling to recreate it. So, you begin to wish that all of the game’s action sequences were proper action sequences — but then you remember how very bad the action-oriented mini-games that do exist actually are, and you have no idea what you want, other than to be playing a different, better game.

What happened? How did a game with such a promising pedigree turn out to be so underwhelming? There is no single answer, but rather a number of probable contributing factors.

One is simply the way that games were sold in 1995. Without its more annoying bits, Full Throttle would offer little more than two hours of entertainment. There’s room for such a game today — a game that could be sold for a small price but in big quantities through digital storefronts. In 1995, however, a game that cost this much to make could reach consumers only as a premium-priced boxed product; other methods of distribution just didn’t exist yet. And consumers who paid $30, $40, or $50 for a game had certain expectations as to how long it should occupy them, as was only reasonable. Thus the need to pad its length to make it suit the realities of the contemporary marketplace probably had more than a little something to do with Full Throttle‘s failings.

Then there’s the Star Wars factor. Many of the people who worked for LucasArts prior to 1993 have commented on what a blessing in disguise it was for George Lucas’s own games studio not to be able to make Star Wars games, a happenstance whose roots can be found in the very first contract Lucas signed to make Star Wars toys just before the release of the very first film in 1977. When another series of accidents finally brought the rights back to Lucasfilm, and by extension to LucasArts, in 1992, the latter jumped on Star Wars with a vengeance, releasing multiple games under the license every year thereafter. This was by no means an unmitigatedly bad thing; at least one of their early Star Wars games, TIE Fighter, is an unimpeachable classic, on par in its own way with any LucasArts adventure game, while many of them evince a free-spirited joie de vivre that’s rather been lost from the franchise’s current over-saturated, overly Disneyfied personification. But it did lead in time to a decline in attention to the non-Star Wars graphic adventures that had previously been the biggest part of LucasArts’s identity. So, it was probably not entirely a coincidence that the LucasArts adventure arm peaked in 1993, just as the Star Wars arm was getting off the ground. In the time between Sam and Max Hit the Road and Full Throttle, adventure games suddenly became a sideline for LucasArts, with perhaps a proportional drop-off in their motivation to make everything in a game like Full Throttle just exactly perfect.

Another factor, one which I alluded to earlier, was the general sense in the industry that the market was now demanding faster paced, more immediate and visceral experiences. And, I rush to add, games with those qualities are fine in themselves. It’s just that that set of design goals may not have been a good pairing with an engine and a genre known for a rather different set of qualities.

These generalized factors were accompanied by more specific collisions of circumstance. When studying the development history of Day of the Tentacle, one comes away with the strong impression that Tim Schafer was the creator most enamored with the jokes and the goofy fiction of the game, while his partner Dave Grossman obsessed mostly over its interactive structure and puzzle design. Perhaps we should not be surprised, then, that when Schafer struck out on his own we got a game with a sparkling fictional presentation and lousy interactive elements.

Full Throttle was not made on the cheap. Far from it: it was the first LucasArts adventure to cost over $1 million to produce. But the money that was thrown at it wasn’t accompanied by a corresponding commitment to the process of making good games. Its development was instead chaotic, improvised rather than planned; Tim Schafer personally took on the titles of Writer, Designer, and Project Leader, and seems to have been well out of his depth on at least the last of them. As a result, the game, which had originally been slated for a Christmas 1994 release, fell badly behind schedule and overran its budget, and what Larry Ahern describes as a “huge section” of it had to be cut out before all was said and done. (Another result of Full Throttle‘s protracted creation was its use of vanilla VGA graphics, which made it something of an anachronism in the spring of 1995, what with the rest of the industry’s shift to higher-resolution SVGA; fortunately, LucasArts’s artists were so talented that their work couldn’t be spoiled even by giant pixels.) During the making of Day of the Tentacle, the design team had regularly brought ordinary folks in off the street to play the latest build and give their invaluable feedback. This didn’t happen for Full Throttle. Instead there was just a mad rush to complete and release a game that nobody had ever really tried to play cold. Alas, this is an old story in the history of adventure games, and a more depressingly typical one than that of the carefully built, meticulously tested game. The only difference on this occasion was that it hadn’t used to be a story set in LucasArts’s offices.

Still, LucasArts paid little price at this time for departing from their old ethos that Design Matters. Full Throttle was greeted by glowing reviews from magazine scribes who were dazzled by its slick, hip presentation, so different from anything else on the gaming scene. For example, the usually thoughtful Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World gave it four and a half out of five stars even as he acknowledged that “its weakest point is its gameplay.” For all that this might strike us today as the very definition of judging a book by its cover, such formulations were par for the course during the madcap multimedia frenzy of the mid-1990s. Tim Schafer claims that the game sold an eventual 1 million copies, enough to make MTV seriously consider turning it into a television cartoon.

Many of those buyers remember Full Throttle fondly today, although a considerable number of naysayers with complaints similar to the ones I’ve aired in this article have also joined the discussion since the game was remastered and re-released in 2017. It seems to me that attitudes toward this game in particular tend to neatly delineate two broad categories of adventure players. There are those who aren’t overly chuffed about puzzles and other issues of design, who consider a modicum of obtuseness to be almost an intrinsic part of the genre, and who thus don’t hesitate to reach for a walkthrough at the first sign of trouble. This is fair enough in itself; as I’ve said many times, there is no wrong way to play any game as long as you’re having fun. I, however, don’t tend to have much fun playing this way. I consider a good interactive design to be a prerequisite to a good game of any stripe. And when I reach for a walkthrough, I do so knowing I’m going to be angry afterward at either myself or the game. If it turns out to be a case of the latter… well, I’d rather just watch a movie.

And indeed, that has to be my final verdict on Full Throttle for those of you who share my own adventure-game predilections: just find yourself a video playthrough to watch, thereby to enjoy its buckets of style and personality without having to wrestle with all of the annoyances. If nothing else, Full Throttle makes for a fun cartoon. Pity about the gameplay.

(Sources: the book Full Throttle: Official Player’s Guide by Jo Ashburn; Computer Gaming World of November 1994 and August 1995; LucasArts customer newsletter The Adventurer of Winter 1994/1995 and Summer 1995; Retro Gamer 62; the “director’s commentary” from the 2017 re-release of Full Throttle. Online sources include interview with Tim Schafer by Celia Pearce and Chris Suellentrop.

A “remastered” version of Full Throttle is available for digital purchase.)

Ian C

July 2, 2021 at 4:04 pm

An interesting overview of a game I didn’t know about before today – sadly, it sounds rather more like a review of a Sierra game, than of a LucasArts product.

Damiano

July 2, 2021 at 4:23 pm

I spoke with Larry Ahern recently in an interview for my website (https://genesistemple.com/interview-with-larry-ahern-lucasarts-crackpot-entertainment-part-1-of-2) and, among the things that didn’t make the cut, I expressed fair surprise that once he himself learned about the failure of the action sequences in Full Throttle, nonetheless he and Ackley decided to try them again while designing The Curse of Monkey Island. That’s why, Larry says, he insisted to make them skippable.

To be fair, they are better implemented than Full Throttle, but I think it can be argued that they’re still mostly their weakest point in an otherwise solid adventure.

John Witte

July 2, 2021 at 4:35 pm

I remember playing it when it first came out in 1995. I was vacationing at a friend’s house and played it on their computer. My memories of it were fonder than your review, Jimmy. I do remember that it was a shorter game and that it was an easier game from Lucasarts. Of the three games that Schafer directed, I always view this one as his most cinematic one, in the sense that it felt more like an interactive movie than an adventure game.

I do enjoy reading your posts and hopefully you will continue writing enough history to get around to Schafer’s magnum opus Grim Fandango.

Brent

July 2, 2021 at 6:44 pm

Love this game and Grim Fandango even though they are both gameplay disasters (I’d argue Grim Fandango even moreso).

Having started playing Sierra adventures at a very young age, by the time this game came out I had long internalized that you were supposed to get stuck in these games for months due to obscure reasons. These days I basically can’t stand adventure games of any kind!

Alan

July 2, 2021 at 6:45 pm

I hate action sequences in my adventure games, so, yeah, the action sequences weren’t great. I’m really terrible at fighting games, so I specifically loathed the bike-to-bike combat. The _idea_ of weapon progression and tradeoffs could work, ironically akin to insult sword fighting in Monkey Island, just with actual violence. But in practice: bletch.

But I ultimatly I loved the game. It’s a pleasure to just wallow in the sheer style of the thing and have an adventure game where thematically appropriate violence works.

I think part of what “killed” adventure games the first time was the idea that games needed action sequences. It’s a pattern that continued for a decade or so into multiple genres. It often works (it popularized real-time strategy games and action oriented RPGs, despite early backlashes against games like Balder’s Gate and Fallout 3), but it definitely felt forced and ill implemented a lot of the time.

An aside: I wouldn’t call Star Wars: Rebel Assault a run-and-gun game. I’d describe it as a rail shooter as you’re stuck with the path the pre-rendered camera go with sprite-based enemies rendered on top.

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2021 at 8:44 pm

That is indeed a better description. Thanks!

Sniffnoy

July 2, 2021 at 7:30 pm

Typo spotting: “cerebation” for “cerebration”; “Disnefied” for… well, I’m not sure if there’s a canonical correct spelling of this, but that one looks wrong. :P

Lisa H.

July 2, 2021 at 7:58 pm

“Disneyfied”, usually.

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2021 at 8:54 pm

Thanks!

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2021 at 8:46 pm

Thanks!

Dan Fabulich

July 2, 2021 at 8:22 pm

We talked about this a few years ago at https://www.filfre.net/2015/07/the-14-deadly-sins-of-graphic-adventure-design/ but I feel like the sense of rage you get at bad puzzles interferes with your ability to enjoy a lot of good adventure games.

But, specifically, it seems like when you give up on a puzzle, you reach for a “walkthrough” and not invisiclues/UHS or other partial/gradual hints. Is that right? Do you never use gradual hints? (Why not? Is it because you’re already so pissed off that you refuse to play the game any further?)

If I may play the role of therapist here, it’s this “all or nothing” approach that amplifies your sense of rage. I agree, once you’re reading a walkthrough, the puzzle of the game really is *ruined*. But don’t you agree that partial/gradual hints only slightly diminish the enjoyment of solving the puzzle? Wouldn’t that be, inherently, less enraging?

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2021 at 9:23 pm

UHS Hints are my first recourse, if they’re available. If I find the failure is on me, fair enough. If it’s on the game — i.e., a bad puzzle — then I turn to a walkthrough, as at that point I know I can’t trust the game.

As far as my “rage” goes… You do have to allow your patient a little bit of hyperbole, Doctor, especially when he’s a writer trying to make a point. ;) While there are things in this world that I really can get angry — perhaps even enraged — about, adventure games are not among them.

mycophobia

July 2, 2021 at 8:22 pm

“Loony Tunes” –> “Looney Tunes”

Jimmy Maher

July 3, 2021 at 1:17 pm

Thanks!

Kai

July 2, 2021 at 9:05 pm

That’s the one latter-day LucasArts adventure I skipped back then, and I don’t think I missed out. Muddy color palettes are just not my thing, and neither is the biker gang milieu. I guess I might not have minded the actual gameplay if the setting and visuals had been to my taste, though.

Leo Vellés

July 2, 2021 at 10:24 pm

I don’t know if it was that i was growing up or what, but as a teenager I always felt that from Sam & Max onwards, LucasArts games droped their quality. None of them felt like a masterpiece to me, unlike the ones that came before. Maybe it was the change from the verb UI to the icons, which I never liked. Sam & Max and Full Throttle, although I replayed them again this year after a decade or two, didn’t cause an impression on me. Although I gotta say that Curse of Monkey Island was pretty good (except the final chapter) and, to this day, I never played Grim Fandango. Shame on me.

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2021 at 10:59 pm

While I would date the start of the decline to after rather than before Sam and Max Hit the Road, I otherwise tend to agree that LucasArts’s designs got at best much more inconsistent after that point.

Arthur

July 2, 2021 at 10:32 pm

I was a LucasArts kid growing up, having played through the preceding adventures (aside from Loom, which I didn’t get around to until last year) and loved them. Full Throttle came out when I was right at the start of my teens, an age when badass dudes on motorbikes seem incredibly cool to young boys and when the somewhat edgier content of Full Throttle would have probably appealed. And I like a good swathe of Full Throttle itself…

…But Full Throttle was also the game which prompted me to stop getting new LucasArts adventures. I got around to playing their Dig-and-onwards adventures eventually, but in every case it was years after release. (Grim Fandango I didn’t play until the remastered version – which, I note, throws in point and click controls!) And it was largely the horrible action sequences that did it.

The thing is, I’d also played some action-oriented games too – I loved Dark Forces, which released the same year. And so, like most videogame-literate folk of my age, I knew full well what a good action sequence played like, and I could tell that the ones in Full Throttle were bad.

A big problem to my mind of both the Road Rash ripoff and the demolition derby is that they look like pure action sequences, but they aren’t. In both case they’re actually puzzles disguised as action sequences, and with (shoddy) action controls with which you are expected to implement the solution. (The Road Rash, sequence, is basically an inventory puzzle, except one which you can fail at if you actually have the right answer, but don’t implement it properly.)

And this means you’re in the worst of all possible worlds. Not only do you have a puzzle which you can fail at solving even when you know exactly what you need to do – bad puzzle design, I think you will agree – but you have a sequence which, because it’s disguised as an action sequence, tricks you into thinking it’s possible to solve it if you just get skilled enough at the action. But you can’t – not without also arriving at the puzzle solution. It’s not just horrible gameplay, it’s horrible communication of what the game expects out of you in the first place.

Nobody who actually played action-oriented games at the time would accept a game as janky as those action sequences, so it beggars belief in retrospect that LucasArts thought people deliberately seeking out an adventure game – some of who might enjoy action sequences, some of whom might hate them – would accept such a thing in an adventure game. My feeling at the time – and I still think my early-teens-self might have had the right instincts about this – was that someone at LucasArts assumed that the target audience for their adventure games wouldn’t be especially versed in action games, and so wouldn’t realise just how subpar the action sequences in Full Throttle were.

I really enjoyed looking over the reasons behind that in your article and I do think you are onto something when you say it’s about playing time issues. I put more of my thoughts on the game – and the LucasArts adventures that followed it – in my blog if you’re interested: https://fakegeekboy.wordpress.com/2020/09/08/gogathon-curses-grimly-market-forces-throttled-a-genre-but-it-escaped-dig-it/

Jimmy Maher

July 2, 2021 at 11:07 pm

That’s a great observation, stating the fundamental problem better than I managed to. And an ironic one, given how masterfully the game adjusts your expectations in the opening adventure sequence.

Venya

July 3, 2021 at 8:07 am

I know this one would not have aged well. I remember beating my head against it when it was new, and then again circa 2001 with the aid of walkthroughs to finally beat it. I’d utterly forgotten the horrible demolition derby minigame until I read this. I enjoyed the story, the game rather less so.

Benedict Singleton

July 3, 2021 at 2:13 pm

Well in some ways it has aged very well. I bought it for three pounds. I got value for money but agree with basically all the comments here. It was a good destruction for a couple of weeks.

Aula

July 3, 2021 at 3:30 pm

“The controls, which are apparently meant to simulate slipping and sliding in the mud of a fairground arena”

Uh, no, that’s a rather thorough misunderstanding of the controls, and actually far more charitable than the game deserves; the reality is much worse than that.

I’m going to guess that you didn’t play Full Throttle with a joystick. If you had, you would have found the controls of the demolition derby minigame pleasingly exact; push the joystick forward of its center position and your car moves forward, pull the joystick back and your car moves backward, tilt the joystick left or right and your car turns left or right, in each case the speed of movement depending on how far off center the joystick is. Of course figuring out what you need to do in order to complete the minigame still wouldn’t be a particularly good puzzle, but it wouldn’t be quite as bad as what you experienced.

So what goes wrong here? To answer that, we need to look at how SCUMM generally uses the joystick. When the joystick is in its center position, the cursor is in the center of the screen; when you move and then hold the joystick, the cursor moves and then stays in place; let go of the joystick, which snaps back to the center, and the cursor returns to screen center. Because of the way SCUMM is designed, the actual game can only read cursor position, so for the minigame to work as described, your car’s movement forward or backward is based on how far the cursor is above or below the horizontal midline of the screen, while its turning left or right is based on how far the cursor is left or right of the vertical midline of the screen. This is fine when the cursor is controlled by a joystick; however, when you use a mouse or the keyboard to move the cursor, this control scheme makes no sense whatsoever. In fact, using a mouse makes this minigame so unplayable that I can only conclude that no one even tried to play it with a mouse during development, and therefore no one ever tried to play through the entire Full Throttle with a mouse before it was released. That would be a gross failure of quality control from almost any company, but from LucasArts it’s utterly mindboggling.

Jimmy Maher

July 3, 2021 at 4:22 pm

I didn’t even know it was *possible* to play it with a joystick…

Arthur

July 3, 2021 at 4:42 pm

I can sort of understand why they might have skimped on that playtesting if they wanted to punt the game out of the door on time and in budget and didn’t mind shipping a somewhat broken game as the consequence of that. Goodness knows Sierra did that often enough.

On the other hand, the same year saw the Dig come out after a development period of six years, which for modern AAA stuff might not be too bad but by the standards of the era was totally absurd. (One could argue that more or less the entire “golden age” of LucasArts adventure came and went whilst they persistently failed to get The Dig done.)

Sure, The Dig had Spielberg’s name attached to it, so it was unlikely to ever be cancelled no matter how deep it got into the weeds. But still, if you’re going to allow a project like that to slip that much but not spend a teeny bit more time and money properly testing Full Throttle, what is wrong with you?

Leo Vellés

July 3, 2021 at 3:40 pm

One more thing about Full Throttle that I think shows why is a flawed game is the tone: it works just fine when the story is told like it’s main caracther: dry, a little bleak líke the setting. But when in it tries to be funny, it fails every single time: when Ben runs to not get caught by the dog in the junkyard, the bit with the bunnies and the land miles…for me, that examples really got me out of the atmosphere the game was building

GeoX

July 3, 2021 at 6:56 pm

I dunno–I still think “not with my box of bunnies!” and “that’s not one of meat’s many uses” are classic lines.

Joshua Barrett

July 3, 2021 at 5:30 pm

This really does seem like a reflection, or even a perfect miniature version, of every single failing that Tim Schafer would manifest in his post-Lucasarts career.

And I say that as someone who absolutely loves Double Fine’s work, but there are some pretty evident problems that have plagued the company from day 1. Every single Double Fine game, almost to a fault, was late, over-budget, and if there were any expectations placed upon it, underwhelming, with only some smaller projects avoiding the curse. Time and again, Schafer has proven himself to be a pretty good writer, an adequate game designer, and a poor manager.

Psychonauts is one of my favorite games, but it’s full of… greater or lesser flaws in its execution. If you compare it to its contemporaries in the genre, it’s less polished than almost any of the others that are fondly remembered in terms of gameplay. It’s full of weird difficulty spikes and awkward controls and occasional bad ideas. The pacing is off, the start of the game is a tutorial level that seems to just drag on, and then two more tutorial levels for good measure afterwards. The reason I and so many others forgive it this is that it’s also a wildly creative game that brings a lot of very cool gameplay ideas to the table (Lungfishopolis, The Milkman Conspiracy, Black Velvetopia, and Waterloo-o being the most famous examples) and then perfectly integrates those ideas into its story so that the mechanics actually convey story and context and feed into the writing, which is really really good. That’s partly because Tim Schafer is pretty funny, and partly because he brought in the also very funny Eric Wolpaw as a co-writer (who will likely come up if and when this blog delves into the 2000s).

All of which is to say that I feel like Full Throttle is a strong signpost of were Schafer’s career went afterwards, and a pretty solid early demonstration of his strengths and weaknesses as a creator.

Terry R

July 5, 2021 at 7:05 pm

I played this game for the first time about a month ago (was a free GoG promotion years ago). Prior to that my only other point-n-click adventure game was The Dig which had a fantastic ambience.

The biker action sequences and the airplane escape sequence felt like playing Don Bluth’s Dragon’s Lair. Simple input sequences with lots of deaths.

The experience of this game felt “thin”. I kept waiting for the “real” game to begin until I noticed the save menu said the game was 63% complete.

CD Master

July 6, 2021 at 5:58 am

Wow! These games are ancient now. Back then, in adventure games like these, we would save the game as ‘ArcadSeq – Derby’ so we could replay they action sequence.

Some space quest and Robin Hood Sierra games had 6 or more mini games! Sure, the quality differed, but it was worth a save file.

Full Throttle should have had more action sequences, that’s for sure. A motorcycle race ala Spy Hunter?

Niall

July 9, 2021 at 1:09 pm

The more I played of Full Throttle back when it first came out, the more I came to respect The Secret of Monkey Island.

In that game, when you finally met the Sword master, you fully expected it to descend into a half-arsed fencing mini-game which you’d have to suffer through for a while to progress. It was simply par-for-the-course in those days.

But instead of Hero-Quest style sword-fighting, they elected to implement battles through something that adventure games traditionally did very well: dialogue. It’s a genius piece of game design, an exemplar of how Lucasfilm planned to do things differently and it has gone on to be maybe the most beloved thing in all their games.

How Full Throttle could have used even an ounce of that kind of outside-the-box thinking and innovation. Instead, Schaefer and his team fell into every trap that an adventure game trying to convey action could. The upshot, ironically, is a game that is utterly turgid.

Thankfully, despite sporting flaws of its own, their next game, Grim Fandango, managed to transcend a poor 3D interface and a few rubbish action puzzles with charm, humour and no shortage of good ideas to offset the bad ones.

John

July 9, 2021 at 6:23 pm

Although I can’t really dispute any of the things that Mr. Maher says about Full Throttle, I nevertheless have a certain fondness for the game. The things that bothered him bothered me also, but not nearly to the same degree. It helped, I think, that I when I first played Full Throttle, I was very much not an adventure gamer. I’d played a few, but never for very long. My impression of adventure games was “the genre where you try using each thing with all of the other things until some arbitrary combination of things finally solves a puzzle”. I can’t say that Full Throttle defied my expectations, exactly. I can say, however, that I found several of its puzzle solutions–combining “my fist” and “the bartender’s face” or combining “my foot” and “the door of that jerk’s trailer”–to be delightfully intuitive and direct by the standards of the genre.

It also helped that Full Throttle came along at around the time where I first began to pay attention to voice acting credits in games and television. Mark Hamill’s Ripburger is a variation on Hamill’s standard villain voice–see also Joker (Batman) and Hobgoblin (Spider-Man)–but one that clearly reflects that Ripburger is old, tired, and fat. Other recognizable voices include Tress MacNeille, Maurice Lamarche, and Kath Soucie. Soucie, the voice of Maureen, is playing rather against type, as I believe she specializes in doing voices for child characters (e.g., the Nickolodeon cartoon Rugrats). Roy Conrad and Hamilton Camp are also good, though I regret to say that I know little about their work outside of Full Throttle.

Then there’s the music. I am one of those people who went out and bought the Gone Jackal’s Bone to Pick album after playing the game. I don’t regret it. I will note, however, that the best songs on the album are generally the ones in the game and that the band has an unfortunate tendency for really long and self-indulgent instrumental segments. The version of the song Born Bad from the game, for example, which plays during the opening credits, is a better, tighter song than the one on the album. I also note that that the band’s lyricist is only about 75% as clever as he thinks he is. Finally, for those who care about such things, I will note that some of the album’s songs are explicitly political. (Born Bad is a protest song. I’m not even kidding. Go listen to the first verse, if you can. The fact that it plays while a bunch of bikers run over a rich guy’s hover limousine is not a coincidence.) I personally don’t mind. Those aren’t quite my personal politics but the album rocks anyway.

Like Terry R above, I played Full Throttle again not too long ago when GOG gave the re-mastered version away for free. I was surprised to see how many of the puzzle solutions I still remembered. I got stuck just a couple of times. The bike-combat section is skippable in the remastered version but the demolition derby section is not. The car is difficult to control but the real problem is that it’s not clear what you’re supposed to be doing with the car in the first place. You can ram Ripburger’s goons’ car all day long and it won’t accomplish anything. The derby is, as Arthur suggested earlier, a puzzle disguised as an action sequence. Once you know the solution to the puzzle–I am not ashamed to confess that I ultimately went and looked it up–it’s not that bad. The controls are awkward, yes, but not insurmountably so. If the solution to the puzzle were more apparent from the beginning I don’t think that people would hate it quite so much. It isn’t until you’ve spent ten minutes fruitlessly trying to ram other cars that the controls become infuriating.

Hoagie

July 10, 2021 at 9:36 pm

I played Full Throttle, The Dig and Grim Fandango many years after their release and disappointed by all, I even thought I had become blasé of graphic adventures. But I quickly understood what went wrong in these games, and I agree with all the points described here: the decline of LucasArts adventures from this game (it’s exactly when they dropped the floppy disks to work exclusively on CD-ROMs, with more cutscenes and spoken dialogues, while keeping an average rhythm of one graphic adventure per year), the fact that Tim Schaffer is good when he works in a team and less good in solo (Grim Fandango has its share of flaws too), the awful “action” sequences (the ones in Indiana Jones 3 & 4 were far better, and sometimes they could be avoided!), some obtuse puzzles… I was also unimpressed by the plot and its predictable twists.

Another letdown not mentioned here is the lack of interactive dialogues. I think there are less than 20 occasions to talk to another character, the huge majority of the dialogues come from the cutscenes. I know the plot takes place in wastelands, but these interactive discussions were a part of the charm of LucasArts games and they added depth to the plot. You don’t even get to know your gangmates?!

It’s a bit of shame that magazines gave Full Throttle positive reviews just because it had LucasArts written on it. I think the only one that really bashed it was Computer Games/Strategy Plus.

Regarding the scenery puzzle, it reminds me of the goat puzzle in Broken Sword/Circle of Blood: both require to think beyond the automatic reflexes we’ve got so used to in graphic adventures, and they look logical in hindsight. But yes, it was unusual among the other puzzles, and it would have been easier to guess with direct control of the character, like in Grim Fandango.

Nate

July 15, 2021 at 12:50 am

I went on a tear through most of the LucasArts adventure catalog a year or two ago, and I recalled Full Throttle being one of the ones I liked well enough in spite of myself. I think the atmosphere and look of the thing won me over. But it’s probably got the least “game” of any of the LucasArts line-up. When it’s doing the adventure-game thing it does alright, but there just isn’t a whole lot of it there. The action parts are…not good, but I don’t recall anything in the game truly frustrating me the way some of the puzzles in Grim Fandango did.

My experiences with both this and Grim Fandango leave me inclined to think that Tim Schaffer is the Tim Burton of video games. He’s good enough to produce something really great, especially in collaboration with someone else, but he’s usually content to have a cool look and atmosphere, and forgets to do the hard work that goes into actual design.

Andrew Nenakhov

July 17, 2021 at 10:13 am

“Worse, you have no idea what you’re even trying to accomplish.” – in Demolition derby they TELL you what to do. You just need listen to what Maureen says.

Had no difficulty with this bit at all.

Sam

July 17, 2021 at 4:23 pm

I recently bought the remastered version on GOG because I remember Full Throttle as probably the best adventure I played in my early teens. But like the author, I was very underwhelmed by the experience of playing the game nowadays and I noticed so many flaws I didn’t recall it had.

I guess it’s just that, a massive change of perspective. When I was young, I had loads of time and probably didn’t mind failing countless times. I probably didn’t mind clicking around pointlessly and try out any possible combination of actions. I don’t remember the puzzles to be unfair or challenging. On the contrary, I think I knew the solution right away and found the puzzles rather easy. I loved the mini games. I remember a complex story and a captivating atmosphere. I remember discussing the game with friends.

None of that magic survived for me as an adult. It’s kind of sad…

threepwood

July 17, 2021 at 8:21 pm

Hello!

A great article as always, but this one sentence kind of bothers me:

“Experimenting with the controls, you discover that you have just three verb icons at your disposal: a skull, a raised fist, and a leather boot.”

The verbs are actually four, since the skull icon has eyes and a mouth that can be clicked. Granted, “look” may not be detrimental to gameplay, but that was a good part of what made adventure games fun to me personally.

Jimmy Maher

July 18, 2021 at 11:21 am

Fair enough. Thanks!

Wolfeye Mox

August 15, 2021 at 5:16 pm

I actually playing Full Throttle. I’m not a fan of adventure games, too much puzzle, not enough fun (for me). But, Full Throttle initially charmed me, I thought “maybe it’s different from those unfun puzzle games”. But, nope, while it had some action scenes, they weren’t fun, instead badly done, and it had puzzles. If a game isn’t fun, to it’s not worth playing, definitely not worth getting out a walkthrough. So, I stopped playing before long. Thought it was me, because I don’t enjoy adventure games, and this was just another one.

But, if you, a fan of adventure games, who enjoys them, thinks it’s gameplay was bad, maybe it wasn’t just me.

Guess that game was all flash and no substance. Shame, because the story is pretty good. Probably will end up watching it on YouTube. But, it’s a failure at being a game.

Wolfeye Mox

August 15, 2021 at 5:18 pm

*played. Really wish you had a way to edit comments. I always seem to catch typos after I posted my comment. Lol

Whybird

August 23, 2021 at 3:30 pm

“One particularly infamous “puzzle” demands that Ben kick a wall over and over at random to discover the one tiny spot that makes something happen.”

This isn’t quite fair. The NPC who’s telling you how to get past it says words to the effect of “I used to open Dad’s secret passage by going to where the crack was at eye level, waiting ’till the meters were all on black, and kicking the wall”.

The trick is remembering that she’s talking about when she was a kid. If you go straight to where the wall is about eye level for a child that age and kick it, it’ll work.

Alex

November 6, 2021 at 8:45 am

Being a fan of Lucas Arts since early childhood, Full Throttle was the last game of theirs I truly enjoyed. Neither The Dig, nor Grim Fandango or the latter Monkey Islands managed to impress me, mostly due to a mix of technical and gameplay-based reasons. Full Throttle truly hit the spot for me. Like most people, I enjoyed the banging soundtrack, but also the scenario, the charakters, the story, the puzzles and the mini-games. I had no problem with them whatsoever. Having said that, it was also the first adventure game I experienced where the presentation promised more than the game itself could keep. I paid more than a hundred bucks for a game I beat in three days. While I never regretted it it could have been so much more. I still catch myself dreaming about the cancelled sequel.

Steve Pitts

October 7, 2025 at 5:20 pm

There is one example of LucasArt’s amongst several correct LucasArts’s

Jimmy Maher

October 10, 2025 at 11:58 am

Thanks!