If you follow the latest developments in modern gaming even casually, as I do, you know that Microsoft and Activision Blizzard recently concluded the most eye-watering transaction ever to take place in the industry: the former acquired the latter for a price higher than the gross national product of more than half of the world’s countries. I find it endlessly amusing to consider that Activision may have lived long enough to set that record only thanks to Infocom, that humble little maker of 1980s text adventures, whose annual revenues — revenues, mind you, not profits — never exceeded $10 million before Activision acquired it in 1986. And just how did this David save a Goliath? It happened like this:

After Bobby Kotick arranged a hostile takeover of a bankrupt and moribund Activision in 1991, he started rummaging through its archives, looking for something that could start bringing some money in quickly, in order to keep the creditors who were howling at his door at bay for a wee bit longer. He came upon the 35 text adventures which had been made by Infocom over the course of the previous decade, games which, for all that they were obviously archaic by the standards of the encroaching multimedia age, were still fondly remembered by many gamers as the very best of their breed. He decided to take a flier on them, throwing twenty of them onto one of those shiny new CD-ROMS that everyone was talking about — or, if that didn’t work for you, onto a pile of floppy disks that rattled around in the box like ice cubes in a pitcher of lemonade. Then he photocopied the feelies and hint books that had gone with the games, bound them all together into two thick booklets, and stuck those in the box as well. He called the finished collection, one of the first notable examples of “shovelware” in gaming, The Lost Treasures of Infocom.

It sold 100,000 or more units, at $60 or $70 a pop and with a profit margin to die for. The inevitable Lost Treasures II that followed, collecting most of the remaining games,[1]The CD-ROM version included fourteen games, missing only Leather Goddesses of Phobos, which Activision attempted to market separately on the theory that sex sells itself. The floppy version included eleven games, lacking additionally three of Infocom’s late illustrated text adventures. was somewhat less successful, but still more than justified the (minimal) effort that had gone into its curation. The two products’ combined earnings were indeed enough to give pause to those creditors who had been pushing for the bankrupt company to be liquidated rather than reorganized.

With a modicum of breathing room thus secured, Kotick scraped together every penny he could find for his Hail Mary pass, which was once again to rely upon Infocom’s legacy. William Volk, his multimedia guru in residence, oversaw the production of Return to Zork, a splashy graphical adventure with all the cutting-edge bells and whistles. In design terms, it was an awful game, riddled with nonsensical puzzles and sadistic dead ends. Yet that didn’t matter at all in the marketplace. Return to Zork rammed the zeitgeist perfectly by combining lingering nostalgia for Zork, Infocom’s best-selling series of games, with all of the spectacular audiovisual flash the new decade could offer up. Upon its release in late 1993, it sold several hundred thousand copies as a boxed retail product, and even more as a drop-in with the “multimedia upgrade kits” (a CD-ROM drive and a sound card in one convenient package!) that were all the rage at the time. It left Activision, if not quite in rude health yet, at least no longer on life support. “Zork on a brick would sell 100,000 copies,” crowed Bobby Kotick.

With an endorsement like that from the man at the top, a sequel to Return to Zork seemed sure to follow. Yet it proved surprisingly long in coming. Partly this was because William Volk left Activision just after finishing Return to Zork, and much of his team likewise scattered to the four winds. But it was also a symptom of strained resources in general, and of currents inside Activision that were pulling in two contradictory directions at once. The fact was that Activision was chasing two almost diametrically opposing visions of mainstream gaming’s future in the mid-1990s, one of which would show itself in the end to have been a blind alley, the other of which would become the real way forward.

Alas, it was the former that was exemplified by Return to Zork, with its human actors incongruously inserted over computer-generated backgrounds and its overweening determination to provide a maximally “cinematic” experience. This vision of “Siliwood” postulated that the games industry would become one with the movie and television industry, that name actors would soon be competing for plum roles in games as ferociously as they did for those in movies; it wasn’t only for the cheaper rents that Kotick had chosen to relocate his resuscitated Activision from Northern to Southern California.

The other, ultimately more sustainable vision came to cohabitate at the new Activision almost accidentally. It began when Kotick, rummaging yet again through the attic full of detritus left behind by his company’s previous incarnation, came across a still-binding contract with FASA for the digital rights to BattleTech, a popular board game of dueling robot “mechs.” After a long, troubled development cycle that consumed many of the resources that might otherwise have been put toward a Return to Zork sequel, Activision published MechWarrior 2: 31st Century Combat in the summer of 1995.

Mechwarrior 2 was everything Return to Zork wasn’t. Rather than being pieced together out of canned video clips and pre-rendered scenes, it was powered by 3D graphics that were rendered on the fly in real time. It was exciting in a viscerally immersive, action-oriented way rather than being a passive spectacle. And, best of all in the eyes of many of its hyper-competitive players, it was multiplayer-friendly. This, suffice to say, was the real future of mainstream hardcore computer gaming. MechWarrior 2′s one similarity with Return to Zork was external to the game itself: Kotick once again pulled every string he could to get it included as a pack-in extra with hardware-upgrade kits. This time, however, the upgrades in question were the new 3D-graphics accelerators that made games like this one run so much better.

In a way, the writing was on the wall for Siliwood at Activision as soon as MechWarrior 2 soared to the stratosphere, but there were already a couple of ambitious projects in the Siliwood vein in the works at that time, which together would give the alternative vision’s ongoing viability a good, solid test. One of these was Spycraft, an interactive spy movie with unusually high production values and high thematic ambitions to go along with them: it was shot on film rather than the standard videotape, from a script written with the input of William Colby and Oleg Kalugin, American and Soviet spymasters during the Cold War. The other was Zork Nemesis.

Whatever else you can say about it, you can’t accuse Zork Nemesis of merely aping its successful predecessor. Where Return to Zork is goofy, taking its cues from the cartoon comedies of Sierra and LucasArts as well as the Zork games of Infocom, Zork Nemesis is cold and austere — almost off-puttingly so, like its obvious inspiration Myst. Then, too, in place of the abstracted room-based navigation of Return to Zork, Zork Nemesis gives you more granular nodes to jump between in an embodied, coherent three-dimensional space, again just like Myst. Return to Zork is bursting with characters, such as that “Want some rye?” guy who became an early Internet meme unto himself; Zork Nemesis is almost entirely empty, its story playing out through visions, written records, and brief snatches of contact across otherwise impenetrable barriers of time and space.

Which style of adventure game you prefer is a matter of taste. In at least one sense, though, Zork Nemesis does undeniably improve upon its predecessor. Whereas Return to Zork’s puzzles seem to have been slapped together more or less at random by a team not overly concerned with the player’s sanity or enjoyment, it’s clear that Zork Nemesis was consciously designed in all the ways that the previous Zork was not; its puzzles are often hard, but they’re never blatantly unfair. Nor do they repeat Return to Zork’s worst design sin of all: they give you no way of becoming a dead adventurer walking without knowing it.

The plot here involves a ruthless alchemical mastermind, the Nemesis of the title, and his quest for a mysterious fifth element, a Quintessence that transcends the standard Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. The game is steeped in the Hermetic occultism that strongly influenced many of the figures who mark the transition from Medieval to Modern thought in our own world’s history, from Leonardo da Vinci to Isaac Newton. This is fine in itself; in fact, it’s a rather brilliant basis for an adventure game if you ask me, easily a more interesting idea in the abstract than yet another Zork game. The only problem — a problem which has been pointed out ad nauseam over the years since Zork Nemesis’s release — is that this game does purport to be a Zork game in addition to being about all that other stuff, and yet it doesn’t feel the slightest bit like Zork. While the Zork games of Infocom were by no means all comedy all the time — Zork III in particular is notably, even jarringly austere, and Spellbreaker is not that far behind it — they never had anything to do with earthly alchemy.

I developed the working theory as I played Zork Nemesis that it must have been originally conceived as simply a Myst-like adventure game, having nothing to do with Zork, until some marketing genius or other insisted that the name be grafted on to increase its sales potential. I was a little sad to be disabused of my pet notion by Laird Malamed, the game’s technical director, with whom I was able to speak recently. He told me that Zork Nemesis really was a Zork from the start, to the point of being listed as Return to Zork II in Activision’s account books before it was given its final name. Nevertheless, I did find one of his choices of words telling. He said that Cecilia Barajas, a former Los Angeles district attorney who became Zork Nemesis‘s mastermind, was no more than “familiar” with Infocom’s Zork. So, it might not be entirely unfair after all to say that the Zork label on Zork Nemesis was more of a convenient way for Barajas to make the game she wanted to make than a wellspring of passion for her. Please don’t misunderstand me; I don’t mean for any of the preceding to come across as fannish gatekeeping, something we have more than enough of already in this world. I’m merely trying to understand, just as you presumably are, why Zork Nemesis is so very different from the Activision Zork game before it (and also the one after it, about which more later).

Of course, a game doesn’t need to be a Zork to be good. And indeed, if we forget about the Zork label, we find that Nemesis (see what I did there?) is one of the best — arguably even the best — of all the 1990s “Myst clones.” It’s one of the rare old games whose critical reputation has improved over the years, now that the hype surrounding its release and the angry cries of “But it’s not a Zork!” have died away, granting us space to see it for what it is rather than what it is not. With a budget running to $3 million or more, this was no shoestring project. In fact, the ironic truth is that both Nemesis’s budget and its resultant production values dramatically exceed those of its inspiration Myst. Its principal technical innovation, very impressive at the time, is the ability to smoothly scroll through a 360-degree panorama in most of the nodes you visit, rather than being limited to an arbitrary collection of fixed views. The art direction and the music are superb, maintaining a consistently sinister, occasionally downright macabre atmosphere. And it’s a really, really big game too, far bigger than Myst, with, despite its almost equally deserted environments, far more depth to its fiction. If we scoff just a trifle because this is yet one more adventure game that requires you to piece together a backstory from journal pages rather than living a proper foreground story of your own, we also have to acknowledge that the backstory is interesting enough that you want to find and read said pages. This is a game that, although it certainly doesn’t reinvent any wheels, implements every last one of them with care.

My own objections are the same ones that I always tend to have toward this sub-genre, and that thus probably say more about me than they do about Nemesis. The oppressive atmosphere, masterfully inculcated though it is, becomes a bit much after a while; I start wishing for some sort of tonal counterpoint to this all-pervasively dominant theme, not to mention someone to actually talk to. And then the puzzles, although not unfair, are sometimes quite difficult — more difficult than I really need them to be. Nemesis is much like Riven, Myst’s official sequel, in that it wants me to work a bit harder for my fun than I have the time or energy for at this point in my life. Needless to say, though, your mileage may vary.

Venus dispenses hints if you click on her. What is the ancient Roman goddess of love, as painted by the seventeenth-century Spanish master Diego Velázquez, doing in the world of Zork? Your guess is as good as mine. Count it as just one more way in which this Zork can scarcely be bothered to try to be a Zork at all.

Released on the same day in April of 1996 as Spycraft, Activision’s other big test of the Siliwood vision’s ongoing viability, Zork Nemesis was greeted with mixed reviews. This was not surprising for a Myst clone, a sub-genre that the hardcore-gaming press never warmed to. Still, some of the naysayers waxed unusually vitriolic upon seeing such a beloved gaming icon as Zork sullied with the odor of the hated Myst. The normally reliable and always entertaining Charles Ardai of Computer Gaming World, the print journal of record for the hobby, whose reviews could still make or break a game as a marketplace proposition even in this dawning Internet age, dinged Zork Nemesis for not having much of anything to do with Infocom’s Zork, which was fair. Yet then he went on to characterize it as a creatively bankrupt, mindless multimedia cash-in, which was not: “Give ’em a gorgeous photo-realistic environment full of fantastic landscapes, some quasi-liturgical groaning on the soundtrack, and a simple puzzle every so often to keep their brains engaged, and you’re off to the bank to count your riches. Throw in some ghostly visions and a hint of the horrific and you can snag the 7th Guest crowd too.” One can only assume from this that Ardai never even bothered to try to play the game, but simply hated it on principle. I maintain that no one who has done so could possibly describe Zork Nemesis‘s puzzles as “simple,” no matter how much smarter than I am he might happen to be.

Even in the face of headwinds like these, Zork Nemesis still sold considerably better than the more positively reviewed Spycraft, seemingly demonstrating that Bobby Kotick’s faith in “Zork on a brick” might not yet be completely misplaced. Its lifetime sales probably ended up in the neighborhood of 150,000 to 200,000 copies — not a blockbuster hit by any means, and certainly a good deal less than the numbers put up by Return to Zork, but still more than the vast majority of Myst clones, enough for it to earn back the money it had cost to make plus a little extra.[2]In my last article, about Cyan’s Riven, I first wrote that Zork Nemesis sold 450,000 copies. This figure was not accurate; I was misreading one of my sources. My bad, as I think the kids are still saying these days. I’ve already made the necessary correction there. Whereas there would be no more interactive spy movies forthcoming from Activision, Zork Nemesis did just well enough that Kotick could see grounds for funding another Zork game, as long as it was made on a slightly less lavish budget, taking advantage of the engine that had been created for Nemesis. And I’m very glad he could, because the Zork game that resulted is a real gem.

With Cecilia Barajas having elected to move on to other things, Laird Malamed stepped up into her role for the next game. He was much more than just “familiar” with Zork. He had gotten a copy of the original Personal Software “barbarian Zork“ — so named because of its hilariously inappropriate cover art — soon after his parents bought him his first Apple II as a kid, and had grown up with Infocom thereafter. Years later, when he had already embarked on a career as a sound designer in Hollywood, a chance meeting with Return to Zork put Activision on his radar. He applied and was hired there, giving up one promising career for another.

He soon became known both inside and outside of Activision as the keeper of the Infocom flame, the only person in the company’s senior ranks who saw that storied legacy as more than just something to be exploited commercially. While still in the early stages of making Activision’s third graphical Zork, he put together as a replacement for the old Lost Treasures of Infocom collections a new one called Classic Text Adventure Masterpieces: 33 of the canonical 35 games on a single CD, with all of their associated documentation in digital format. (The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Shogun, Infocom’s only two licensed titles, were the only games missing, in both cases because their licensing contracts had expired). He did this more because he simply felt these games ought to be available than because he expected the collection to make a lot of money for his employer. In the same spirit, he reached out to the amateur interactive fiction community that was still authoring text adventures in the Infocom mold, and arranged to include the top six finishers from the recently concluded First Interactive Fiction Competition on the same disc. He searched through Activision’s storage rooms to find a backup of the old DEC mainframe Infocom had used to create its games. This he shared with Graham Nelson and a few other amateur-IF luminaries, whilst selecting a handful of interesting, entertaining, and non-embarrassing internal emails to include on the Masterpieces disc as well.[3]This “Infocom hard drive” eventually escaped the privileged hands into which it was entrusted, going on to cause some minor scandals and considerable interpersonal angst; suffice to say that not all of its contents were non-embarrassing. I have never had it in my possession. No, really, I haven’t. It’s been rendered somewhat moot in recent years anyway by the stellar work Jason Scott has done collecting primary sources for the Infocom story at archive.org. No one at Activision had ever engaged with the company’s Infocom inheritance in such an agenda-less, genuine way before him; nor would anyone do so after him.

He brought to the new graphical Zork game a story idea that had a surprisingly high-brow inspiration: the “Grand Inquisitor” tale-within-a-tale in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1880 novel The Brothers Karamazov, an excerpt which stands so well on its own that it’s occasionally been published that way. I can enthusiastically recommend reading it, whether you tackle the rest of the novel or not. (Laird admitted to me when we talked that he himself hadn’t yet managed to finish the entire book when he decided to use a small part of it as the inspiration for his game.) Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor is a leading figure of the Spanish Inquisition, who harangues a returned Jesus Christ for his pacifism, his humility, and his purportedly naïve rejection of necessary hierarchies of power. It is, in other words, an exercise in contrast, setting the religion of peace and love that was preached by Jesus up against what it became in the hands of the Medieval Catholic popes and other staunch insitutionalists.

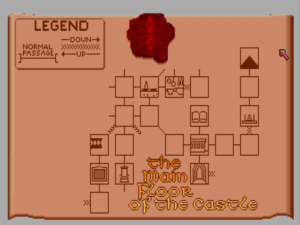

For its part, Zork: Grand Inquisitor doesn’t venture into quite such politically fraught territory as this. Its titular character is an ideological rather than religious tinpot dictator, of the sort all too prevalent in the 20th and 21st centuries on our world. He has taken over the town of Port Foozle, where he has banned all magic and closed all access to the Great Underground Empire that lies just beneath the town. You play a humble traveling salesperson who comes into possession of a magic lantern — a piece of highly illegal contraband in itself — that contains the imprisoned spirit of Dalboz of Gurth, the rightful Dungeon Master of the Empire. He encourages and helps you to make your way into his forbidden realm, to become a literal underground resistance fighter against the Grand Inquisitor.

The preceding paragraphs may have led you to think that Zork: Grand Inquisitor is another portentous, serious game. If so, rest assured that it isn’t. Not at all. Its tone and feel could hardly be more different from those of Zork Nemesis. Although there are some heavy themes lurking in the background, they’re played almost entirely for laughs in the foreground. This strikes me as no bad approach. There are, after all, few more devastating antidotes to the totalitarian absurdities of those who would dictate to others what sort of lives they should lead and what they should believe in than a dose of good old full-throated laughter. As Hannah Arendt understood, the Grand Inquisitors among us are defined by the qualities they are missing rather than any that they possess: qualities like empathy, conscience, and moral intelligence. We should not hesitate to mock them for being the sad, insecure, incompletely realized creatures they are.

Just as I once suspected that Zork Nemesis didn’t start out as a Zork game at all, I was tempted to assume that this latest whipsaw shift in atmosphere for Zork at Activision came as a direct response to the vocal criticisms of the aforementioned game’s lack of Zorkiness. Alas, Laird Malamed disabused me of that clever notion as well. Grand Inquisitor was, he told me, simply the Zork that he wanted to make, initiated well before the critics’ and fans’ verdicts on the last game started to pour in in earnest. He told me that he practically “begged” Margaret Stohl, who has since gone on to become a popular fantasy novelist in addition to continuing to work in games, to come aboard as lead designer and writer and help him to put his broad ideas into a more concrete form, for he knew that she possessed exactly the comedic sensibility he was going for.

Regardless of the original reason for the shift in tone, Laird and his team didn’t hesitate to describe Grand Inquisitor later in its development cycle as a premeditated response to the backlash about Nemesis’s Zork bona fides, or rather its lack thereof. This time, they told magazines like Computer Gaming World, they were determined to “let Zork be Zorky”: “to embrace what was wonderful about the old text adventures, a fantasy world with an undercurrent of humor.”

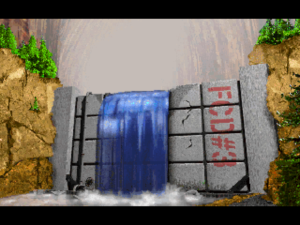

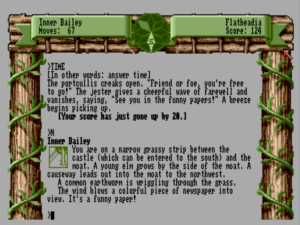

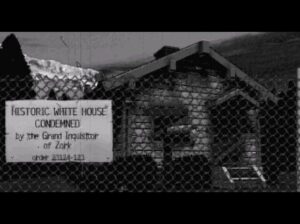

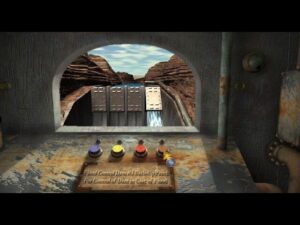

Certainly Grand Inquisitor doesn’t lack for the concrete Zorkian tropes that were also all over Return to Zork. From the white house in the forest to Flood Control Dam #3 to Dalboz’s magic lantern itself, the gang’s all here. But all of these disparate homages are integrated into a larger Zorkian tapestry in a way Activision never managed elsewhere. Return to Zork is a compromised if not cynical piece of work, its slapstick tone the result of a group of creators who saw Zork principally as a grab bag of tropes to be thrown at the wall one after another. And Nemesis, of course, has little to do with Zork at all. But Grand Inquisitor walks like a Zork, talks like a Zork, and is smart amidst its silliness in the same way as a Zork of yore. In accordance with its heritage, it’s an unabashedly self-referential game, well aware of the clichés and limitations of its genre and happy to poke fun at them. For example, the Dungeon Master here dubs you the “AFGNCAAP”: the “Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person,” making light of a longstanding debate, ancient even at the time of Grand Inquisitor’s release, over whether it must be you the player in the game or whether it’s acceptable to ask you to take control of a separate, strongly characterized protagonist.

It’s plain from first to last that this game was helmed by someone who knew Zork intimately and loved it dearly. And yet the game is never gawky in that obsessive fannish way that can be so painful to witness; it’s never so much in thrall to its inspiration that it forgets to be its own thing. This game is comfortable in its own skin, and can be enjoyed whether you’ve been steeped in the lore of Zork for decades or are coming to it completely cold. This is the way you do fan service right, folks.

Although it uses an engine made for a Myst-like game, Grand Inquisitor plays nothing like Myst. This game is no exercise in contemplative, lonely puzzle-solving; its world is alive. As you wander about, Dungeon Master Dalboz chirps up from his lantern constantly with banter, background, and subtle hints. He becomes your friend in adventure, keeping you from ever feeling too alone. In time, other disembodied spirits join you as well, until you’re wandering around with a veritable Greek chorus burbling away behind you. The voice acting is uniformly superb.

Another prominent recurring character is Antharia Jack, a poor man’s Indiana Jones who’s played onscreen as well as over the speakers by Dirk Benedict, a fellow very familiar with being a stand-in for Harrison Ford in his most iconic roles, having also played the Han Solo-wannabee Starbuck in the delightfully cheesy old television Star Wars cash-in Battlestar Galactica. Benedict, one of those actors who’s capable of portraying exactly one character but who does it pretty darn well, went on to star in The A-Team after his tenure as an outer-space fighter jockey was over. His smirking, skirt-chasing persona was thus imprinted deeply on the memories of many of the twenty-somethings whom Activision hoped to tempt into buying Grand Inquisitor. This sort of stunt-casting of actors a bit past their pop-culture prime was commonplace in productions like these, but here at least it’s hard to fault the results. Benedict leans into Antharia Jack with all of his usual gusto. You can’t help but like the guy.

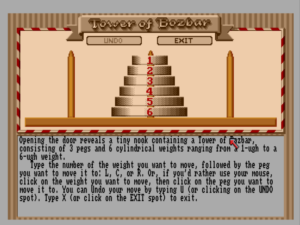

When it comes to its puzzles, Grand Inquisitor’s guiding ethic is to cut its poor, long-suffering AFGNCAAP a break. All of the puzzles here are well-clued and logical within the context of a Zorkian world, the sort of puzzles that are likely to stump you only just long enough to make you feel satisfyingly smart after you solve them. There’s a nice variety to them, with plenty of the “use object X on thing Y” variety to go along with some relatively un-taxing set-piece exercises in pushing buttons or pulling levers just right. But best of all are the puzzles that you solve by magic.

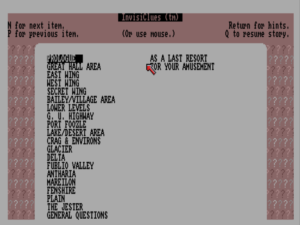

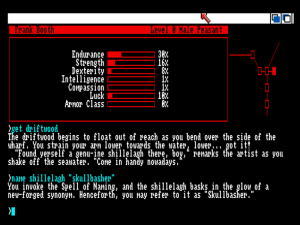

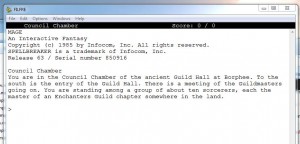

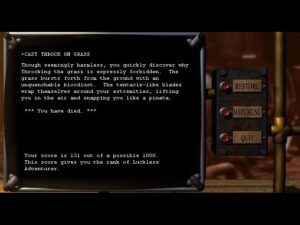

Being such a dedicated Infocom aficionado, Laird Malamed remembered something that most of his colleagues probably never knew at all: that the canon of Infocom Zork games encompassed more than just the ones that had that name on their boxes, that there was also a magic-oriented Enchanter trilogy which took place in the same universe. At the center of those games was one of the most brilliant puzzle mechanics Infocom ever invented, a system of magic that had you hunting down spell scrolls to copy into your spell book, after which they were yours to cast whenever you wished. This being Infocom, however, they were never your standard-issue Dungeons & Dragons Fireball spells, but rather ones that did weirdly specific, esoteric things, often to the point that it was hard to know what they were really good for — until, that is, you finally stumbled over that one nail for which they were the perfect hammer. Grand Inquisitor imports this mechanic wholesale. Here as well, you’re forever trying to figure out how to get your hands on that spell scroll that’s beckoning to you teasingly from the top of a tree or wherever, and then, once you’ve secured it, trying to figure out where it can actually do something useful for you. This latter is no trivial exercise when you’re stuck with spells like IGRAM (“turn purple things invisible”) and KENDALL (“simplify instructions”). Naturally, much of the fun comes from casting the spells on all kinds of random stuff, just to see what happens. Following yet again in the footsteps of Infocom, Laird’s team at Activision implemented an impressive number of such interactions, useless though they are for any purpose other than keeping the AFGNCAAP amused.

Grand Inquisitor isn’t an especially long game on any terms, and the fairly straightforward puzzles mean you’ll sail through what content there is much more quickly than you might through a game like Nemesis. All in all, it will probably give you no more than three or four evenings’ entertainment. Laird Malamed confessed to me that a significant chunk of the original design document had to be cut in the end in order to deliver the game on-time and on-budget; this was a somewhat marginal project from the get-go, not one to which Activision’s bean counters were ever going to give a lot of slack. Yet even this painful but necessary surgery was done unusually well. Knowing from the beginning that the scalpel might have to come out before all was said and done, the design team consciously used a “modular” approach, from which content could be subtracted (or added, if they should prove to be so fortunate) without undermining the structural integrity, if you will, of the game as a whole. As a result of their forethought, Grand Inquisitor doesn’t feel like a game that’s been gutted. It rather feels very complete just as it is. Back in the day, when Activision was trying to sell it for $40 or $50, its brevity was nevertheless a serious disadvantage. Today, when you can pick it up in a downloadable version for just a few bucks, it’s far less of a problem. As the old showbiz rule says, better to leave ’em wanting more than wishing you’d just get off the stage already.

“You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door.” Unfortunately, the property has been condemned by the Grand Inquisitor. “Who is the boss of you? Me! I am the boss of you!”

The “spellchecker” is a good example of Grand Inquisitor’s silly but clever humor, which always has time for puns. The machine’s purpose is, as you might have guessed, to validate spell scrolls.

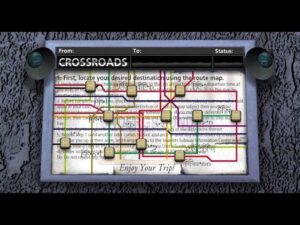

This subway map looks… complicated. Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a way to simplify it in a burst of magic? Laird told me that this puzzle was inspired by recollections of trying to make sense of a map of the London Underground as a befuddled tourist.

Nothing sums up the differences between Zork Nemesis and Zork: Grand Inquisitor quite so perfectly as the latter’s chess puzzle. In Nemesis, you’d be futzing around with this thing forever. And in Grand Inquisitor? As Scorpia wrote in her review for Computer Gaming World, “Think of what you’ve [always] felt like doing with an adventure-game chess puzzle, and act accordingly.”

There are some set-piece puzzles that can’t be dispatched quite so easily. An instruction booklet tells you to never, ever close all four sluices of Flood Control Dam Number 3 at once. So what do you try to do?

Playing Strip Grue, Fire, Water with Antharia Jack. The cigars were no mere affectation of Dirk Benedict. His costars complained repeatedly about the cloud of odoriferous smoke in which he was constantly enveloped. A true blue Hollywood eccentric of the old-school stripe, Benedict remains convinced to this day that the key to longevity is tobacco combined with a macrobiotic diet. Ah, well… given that he’s reached 79 years of age and counting as of this writing, it seems to be working out for him so far.

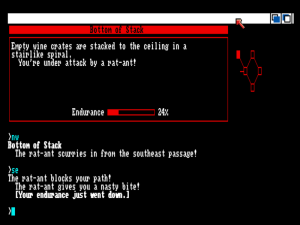

Be careful throwing around them spells, kid! Deaths in Grand Inquisitor are rendered in text. Not only is this a nice nostalgic homage to the game’s roots, it helped to maximize the limited budget by avoiding the expense of portraying all those death scenes in graphics.

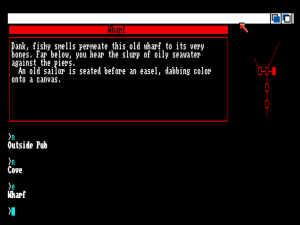

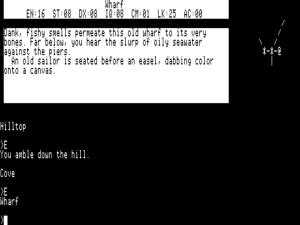

Laird Malamed had no sense during the making of Grand Inquisitor that this game would mark the end of Zork’s long run. On the contrary, he had plans to turn it into the first game of a new trilogy, the beginning of a whole new era for the venerable franchise. In keeping with his determination to bring Zork back to the grass roots who knew and loved it best, he came up with an inspired guerrilla-marketing scheme. He convinced the former Infocom Implementors Marc Blank and Mike Berlyn to write up a short text-adventure prelude to the story told in Grand Inquisitor proper. Then he got Kevin Wilson, the organizer of the same Interactive Fiction Competition whose games had featured on the Masterpieces CD, to program their design in Inform, a language that compiled to the Z-Machine, Infocom’s old virtual machine, for which interpreters had long been available on countless computing platforms, both current and archaic. Activision released the end result for free on the Internet in the summer of 1997, as both a teaser for the graphical game that was to come and a proof that Zork was re-embracing its roots. Zork: The Undiscovered Underground isn’t a major statement by any means, but it stands today, as it did then, as a funny, nostalgic final glance back to the days when Zork was nothing but words on a screen.

Unfortunately, all of Laird’s plans for Zork’s broader future went up in smoke when Grand Inquisitor was released in November of 1997 and put up sales numbers well short of those delivered by Nemesis, despite reviews that were almost universally glowing this time around. Those Infocom fans who played it mostly adored it for finally delivering on the promise of its name, even if it was a bit short. The problem was that that demographic was now moving into the busiest phase of life, when careers and children tend to fill all of the hours available and then some. There just weren’t enough of those people still buying games to deliver the sales that a mass-market-focused publisher like Activision demanded, even as the Zork name meant nothing whatsoever to the newer generation of gamers who had cut their teeth on DOOM and Warcraft. Perhaps Bobby Kotick should have just written “Zork” on a brick after all, for Grand Inquisitor didn’t sell even 100,000 units.

And so, twenty years after a group of MIT graduate students had gotten together to create a game that was even better than Will Crowther and Don Woods’s Adventure, Zork’s run came to an end, taking with it any remaining dregs of faith at Activision in the Siliwood vision. Apart from one misconceived and blessedly quickly abandoned effort to revive the franchise as a low-budget MMORPG during the period when those things were sprouting like weeds, no Zork game has appeared since. We can feel sad about this if we must, but the reality is that nothing lasts forever. Far better, it seems to me, for Zork to go out with Grand Inquisitor, one of the highest of all its highs, than to be recycled again and again on a scale of diminishing returns, as has happened to some other classic gaming franchises. Likewise, I’m kind of happy that no one who made Grand Inquisitor knew they were making the very last Zork adventure. Their ignorance caused them to just let Zork be Zork, meant they were never even tempted to turn their game into some over-baked Final Statement.

In games as in life, it’s always better to celebrate what we have than to lament what might have been. With that in mind, then, let me warmly recommend Zork: Grand Inquisitor to any fans of adventure games among you readers who have managed not to play it yet. It really doesn’t matter whether you know the rest of Zork or not; it stands just fine on its own. And that too is the way it ought to be.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Zork Nemesis: The Official Strategy Guide by Peter Spear and Zork: Grand Inquisitor: The Official Strategy Guide by Margaret Stohl; Computer Gaming World of August 1996, February 1997, and March 1998; InterActivity of May 1996; Next Generation of August 1997; Los Angeles Times of November 30 1996.

Online sources include a 1996 New Media profile of Activision and “The Trance Experience of Zork Nemesis“ at Animation World.

My thanks to Laird Malamed for taking the time from his busy schedule to talk to me about his history with Zork. Note that any opinions expressed in this article that are not explicitly attributed to him are my own.

Zork Nemesis and Zork: Grand Inquisitor are both available as digital purchases at GOG.com.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The CD-ROM version included fourteen games, missing only Leather Goddesses of Phobos, which Activision attempted to market separately on the theory that sex sells itself. The floppy version included eleven games, lacking additionally three of Infocom’s late illustrated text adventures. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In my last article, about Cyan’s Riven, I first wrote that Zork Nemesis sold 450,000 copies. This figure was not accurate; I was misreading one of my sources. My bad, as I think the kids are still saying these days. I’ve already made the necessary correction there. |

| ↑3 | This “Infocom hard drive” eventually escaped the privileged hands into which it was entrusted, going on to cause some minor scandals and considerable interpersonal angst; suffice to say that not all of its contents were non-embarrassing. I have never had it in my possession. No, really, I haven’t. It’s been rendered somewhat moot in recent years anyway by the stellar work Jason Scott has done collecting primary sources for the Infocom story at archive.org. |