It’s all too easy to underestimate Steve Meretzky. Viewed from on high, his career is a long series of broad science-fiction or fantasy comedies — fun enough, sure, but not exactly the most challenging fare. Meretzky, it would seem, learned what worked for him in 1983 when he wrote his first game Planetfall and then just kept on doing it. The lukewarm commercial and critical response to his one great artistic experiment, 1985’s A Mind Forever Voyaging, only hardened the template that would hold true for the remainder of his career.

Such a dismissive summary, however, is unfair in at least a couple of ways. First of all, it fails to give due credit to Meretzky’s sheer design craft. By the time he entered the second half of the 1980s with a few games under his belt, he was second to no one on the planet in his ability to craft entertaining and fair puzzles, to weave them together into a seamless whole, and to describe it all concisely and understandably. Secondly, and more subtly, his games weren’t always quite as safe as they first appeared. Merezky often if not always found ways within his established templates to challenge his players’ expectations and give critics like me something to talk about all these years later: the endearing Floyd and his shocking death in Planetfall; the political statement in the era of Ronald Reagan and the Moral Majority that sex could be fun rather than dirty — arguably more effective in its easy-going way than A Mind Forever Voyaging‘s more hectoring tone — that’s embedded within Leather Goddesses of Phobos. Nowhere are Meretzky’s talent for pure game design and his willingness to slyly subvert his wheelhouse genre more highlighted than in Stationfall, his game of 1987.

A sequel to Planetfall had been quite a long time coming. Floyd had offhandedly promised one at the end of that game, but any plans Meretzky may have had to turn it into a franchise were overwhelmed by Infocom’s need to get the next Enchanter trilogy game done, the need for a Douglas Adams collaborator, and soon enough by new ideas from Meretzky himself. After the Activision buyout, with Infocom in general becoming much more willing to mine their own past in search of that elusive, much-needed hit, he debated for some time whether to do a Planetfall sequel at last or a new Zork game. In the end Brian Moriarty took Zork, and thus the die was cast. Meretzky’s sixth and, as it would transpire, final all-text adventure game would be a sequel to his first.

Stationfall reunites you almost immediately with Floyd, the lovable robot companion who remains for most players the most memorable aspect of Planetfall. Your exploits in the first game led to a promotion from Ensign Seventh Class to Lieutenant First Class, but your actual duties aren’t much more interesting now than they were then. Instead of pushing a mop around, you now spend your days pushing paper around. Your assignment for today is to take a space truck from your ship to a nearby space station to pick up a set of “Request for Stellar Patrol Issue Regulation Black Form Binders Request Form Forms” — something of an Infocom in-joke, an extrapolation of Meretzky’s love for real-life “memo hacking”. You pick up a robot from the pool to help you on the trip, and, lo and behold, it turns out to be good old Floyd, whom you’ve seen “only occasionally since he opted for assignment in the Stellar Patrol those five long years ago.” When you and Floyd arrive at your destination, you find it deserted. Where has everyone gone? Much like in Planetfall, you will have to figure out what happened here and how to stop it from continuing to happen if you hope to escape alive.

Floyd is in as fine a form as ever. Some parts of his schtick are recycled from the first game, other parts adorably new.

>sit in pilot seat

You are now in the pilot seat. Floyd clambers into the copilot seat, his feet dangling a few centimeters short of the floor. "Let Floyd launch the spacetruck? Please? Floyd has not crashed a truck in over two weeks!"

>floyd, launch spacetruck

"Floyd changed his mind. Controls too scary-looking."

As in the first game, part of the genius of Floyd is that you never know quite what he really looks like. You hear at various times that he has legs, eyes, can cry oily tears and can smile, but you get no explicit description. This leaves each player to construct her own idealized image, whether based on kittens or puppies or children or whatever represents the ultimate Cute for her personally.

Floyd, of course, simply has to be in any game that dares to bill itself as a sequel to Planetfall. More notable is just how thoroughly Stationfall embraces the idea of being a sequel in other ways. The deserted planetside research complex has been replaced with a deserted space station, but otherwise the environments are remarkably similar. Like in Planetfall, you’re racing against a deadly disease that will kill you if you take too long. Other aspects of Stationfall are so faithful to the original as to feel downright anachronistic in an Infocom game of this late vintage. Hunger and sleep timers make their first appearance in years, and the environment is liberally sprinkled, although not quite so maddeningly as in Planetfall, with red herrings and rooms whose only purpose is to add verisimilitude. Among the latter, for example, are the ubiquitous “SanFacs,” included here just as they were in Planetfall as an answer for every kid who ever watched Star Trek and asked just where you pooped aboard the Enterprise. The returning elements are so numerous as to feel pointless to try to exhaustively catalog: the yucky but good-tasting goo that is the staple of your diet; the tape spools you use in combination with the library’s reader to ferret out clues; the magnetic key cards that are cruelly easy to corrupt and thereby lock yourself out of victory (one of my few quibbles with a mostly superb game design); the control-room monitors that helpfully break down the status of every subsystem into a simple green, yellow, or red. It’s all so similar that the differences, like the realization that your goal this time isn’t to actually repair the station, arrive as something of a shock.

Yet if Stationfall is by conscious choice a throwback, it’s also a testament to just how far Steve Meretzky had come as a designer in the four years since Planetfall. That first game he ever wrote can feel at times like it’s rambled out of its maker’s control, leaving its various bits and pieces to dangle unconnected in the breeze. Stationfall in contrast is air-tight; even its red herrings are placed with purpose. Meretzky knows exactly what he’s doing at every juncture, is in complete control of his craft; all of its bits and pieces fit together seamlessly. Particularly noticeable is just how much better of a writer Meretzky has become, the continuation of a trend that began to reach a certain fruition in 1986’s Leather Goddesses, the game for which Infocom’s unsung hero Jon Palace made a special effort to help him to “sensualize” his text. Almost entirely gone now are the off-hand, even lazy descriptions that creep into Meretzky’s early games, when he tended to tell too much and show too little in his hurry to get to the next really exciting part. I’m tempted to give you an example at this point, but, textual sensualizing or no, he still isn’t the kind of writer that dazzles you with his poetry. Stationfall‘s text is rather impressive in the cumulative. After playing for a long while, you begin to realize that its simple, sturdy diction has quietly given you a pretty darn good sense of where you are and what you’re doing.

Lest it all start to feel too dry, the robots are a constant source of amusement. I say “robots” here because early on you find another friend to join you and Floyd, a gangly, chatty metal nerd named Plato — C-3PO to Floyd’s R2-D2 — who proves almost as lovable.

"I am quite surprised to discover you here," says the robot. "I have not seen a soul for a day now, perhaps more. But look, here I am forgetting my manners again. I am known as Plato to the humans on this station, and I am most gratified to make your acquaintance."

Plato reaches the last page of his book. "Heavens! It appears to be time for another jaunt to the library. Would you care to accompany me, my boisterous friend?"

"Oh boy yessiree!" says Floyd, bounding off after Plato. "I hope they have copies of my favorite comic, THE ADVENTURES OF LANE MASTODON!"

Floyd really ought to go into advertising as a product-placement expert…

The remainder of this article will spoil the plot and ending of Stationfall (and Planetfall as well), along with a couple of the final puzzle solutions. If you want to experience Stationfall unspoiled, by all means go do so and come back later. The experience of playing with no preconceptions is well worth having.

And then, perhaps at about the point when you’re really starting to appreciate just what a well-crafted and charming traditional adventure game you’re playing, Stationfall starts to get deeply, creepily weird.

Like so much else in Stationfall, its darker shadings don’t arise completely out of the blue. Some of the same atmosphere of dread and paranoia was lurking beneath the surface goofiness in Planetfall as well; the background to that game was after all a devastating pandemic that was slowly killing you as well as you messed about with Floyd and chowed down on colored goo. Stationfall, however, slowly becomes darker and more subversive than its predecessor ever dared. To understand the difference between the games, we might begin by noting how their plots unfold. In Planetfall you can revive virtually the entire population of the planet Resida after discovering the cure for the pandemic that has struck it, effectively turning back the clock and making everything right again — including, as it turns out, the supposedly “dead” Floyd. In Stationfall, dead is dead; the crew of the space station is gone and they’re not coming back. It feels like the work of an older, more world-weary writer. Yet even that description doesn’t quite get to the heart of the tonal shift that Stationfall undergoes over the course of your playing. It becomes a comedic text adventure filtered through the sensibility of David Lynch, unsettling and just somehow off in ways that are hard to fully describe.

But describe it I must — that’s why we’re here, isn’t it? — so maybe I should start by explaining what’s actually going on on this station. In yet one more homage to Planetfall, it has indeed been infected by a deadly virus. This, however, is a virus of another stripe, computerized rather than biological. It infects any machinery with which it comes into contact, causing the gadgets that make life possible in space to gradually “turn against their creators.” This, then, is the fate that’s been suffered by the people who used to crew the station. As you wander about the station and time passes, you begin to see more and more evidence of the process that’s underway. The automatic doors, for instance, no longer whisk efficiently open and shut for you, but open “barely wide enough for you to squeeze through. As you do so, the door tries to shut, almost jamming against you!” (This progression doesn’t quite make logical sense, as the station has already killed its entire crew, but it’s so effective in context that I’m happy not to nitpick unduly.)

Creepiest of all is what begins to happen to Plato and your old buddy Floyd. The messages describing their antics begin to change, subtly at first but then unmistakably.

Floyd produces a loud burp and fails to apologize.

Floyd stomps on your foot, for no apparent reason.

Floyd meanders in. "You doing anything fun?" he asks, and then answers his own question, "Nope. Same dumb boring things." You notice that Plato has also roamed into view behind Floyd, once again absorbed in his reading.

"Let us take a stroll, Floyd," says Plato, tucking his book under one arm. "Tagging along after this simpleton human is becoming tiresome." He breezes out. Floyd hesitates, then follows.

It’s Plato who tries to kill you first, whereupon Floyd comes to your rescue one last time. But his resistance to the virus won’t last much longer. When you try to hug him to thank him for his deed, “Floyd sniffs, ‘Please leave Floyd alone for a while.'” He shows up from time to time after that, growing ever more rude and petulant. And then he’s simply gone, who knows where, doing who knows what. By now any traces of goofy comedy are long gone. Many players of Planetfall have described how much they missed Floyd after his final sacrifice for their sake, how empty and lonely the complex suddenly felt. Yet that feeling of bereavement was as nothing compared to the creeping dread you’re now feeling, waiting for Floyd to show up again, quite possibly to kill you, as everything around you continues to feel ever more subtly, dangerously wrong.

And then, if you survive long enough, you make it to the climax and you do indeed meet Floyd again, in another deeply unsettling scene that juxtaposes the old, playful companion you used to know with whatever it is he’s become: “Floyd is standing between you and the pyramid, his face so contorted by hate as to be almost unrecognizable. You also wonder where he picked up that black eye patch.” You can picture the old Floyd coming across an eye patch like that and putting it on with one of his squeals of delight. Now, though… it’s all just so wrong.

To win Stationfall you have to kill Floyd. It’s the strangest, most disturbing ending to an Infocom game this side of Trinity — far more disturbing in my eyes than that of Infidel, Mike Berlyn’s stab at an interactive tragedy, in that that game held you always at an emotional remove from the doomed persona you played, who was never depicted as anything other than a selfish jerk anyway. This, though… this is Floyd, the most beloved character Infocom ever created.

>put foil on pyramid

As you approach the pyramid, Floyd levels his stun ray at you, so you quickly back off.

Floyd fires his stun ray nonchalantly in your direction, laughing, as though taunting you. You feel part of your leg go numb.

>shoot floyd with zapgun

The bolt hits Floyd squarely in the chest. He is blown backwards, against the pedestal, and slumps to the deck.

>put foil on pyramid

The foil settles over the pyramid like a blanket, reflecting the pyramid's evil emanations right back into itself. A reverberating whine, like an electronically amplified beehive, fills the room. The whine grows louder and louder, the pyramid and its pedestal begin vibrating, and the sharp smell of ozone assaults you.

The noise and the smell and the vibration overwhelm you. As your knees buckle and you drop to the deck, the pyramid explodes in a burst of intense white light. The explosion leaves you momentarily blinded, but you can hear a mechanized voice on the P.A. system, getting slower and deeper like a stereo disc that has lost its power: "Launch aborted -- launch -- abort --"

The replica pyramids fade to darkness, and a subtle change in background sound tells you that the space station's systems and machinery are returning to their normal functions.

Still dazed, you crawl over to Floyd, lying in a smoking heap near the blackened pedestal. Damaged beyond any conceivable repairs, he half-opens his eyes and looks up at you for the last time. "Floyd sorry for the way he acted. Floyd knows...you did what you...had to do." Wincing in pain, he slowly reaches over to touch your hand. "One last game of Hider-and-Seeker? You be It. Ollie ollie..." His voice is growing weaker. "...oxen..." His eyes close. "...free..." His hand slips away from yours, and he slumps backwards, lifeless. One of his compartments falls open, and Floyd's favorite paddleball set drops to the deck.

In the long silence that follows, something Plato said echoes through your mind. "...think instead about the joy-filled times when you and your friend were together." A noise makes you turn around, and you see Oliver, the little robot that stirred such brotherly feelings in Floyd. Toddling over to you on unsteady legs, he looks uncomprehendingly at Floyd's remains, but picks up the paddleball set. Oliver looks up at you, tugs on the leg of your Patrol uniform, and asks in a quavering voice, "Play game... Play game with Oliver?"

I complained at some length in my article on Planetfall about the ending to that game, how it undercut the pathos of Floyd’s noble sacrifice by bringing him back, all repaired and shined up and good as new again. The natural first question to ask here, then, is why he’s not similarly repairable this time.

Setting aside such practical questions in the name of dramatic effect, I’m not entirely sure how to feel about this scene. Even more so than that of Floyd’s first death (itself a bit of one-upsmanship inspired by Electronic Arts’s early “Can a Computer Make You Cry?” advertisements), it feels a little manufactured. It’s as if Meretzky, having failed to stick to his dramatic guns the first time around, has decided to make up for it with interest by not only killing Floyd for good this time but by making you put him down yourself. On the other hand, the scene’s very tonal discordance feels part and parcel of the increasingly surreal journey the game as a whole has become. The appearance of a new “baby” robot that’s apparently supposed to make everything all better feels for me like the strangest element of all. It’s common in tragic literature going back to Shakespeare and well before to end an orgy of death and destruction with a glimmer of hope in the form of new life, a reminder that a new spring always follows every winter and that life in all its comedy and tragedy and joy and pain does go on for the world at large. Yet if that’s the intent here it’s handled rather clumsily. It just feels like Floyd is being replaced, and only adds to the Lynchian oddity of the whole experience. I suspect the weirdness of this final scene is due more to the tone finally starting to get away from Meretzky — aided no doubt by the fact that he was pushing right up against the limits of the 128 K Z-Machine, and didn’t have space to write more — than authorial intent. Nevertheless, effectively weird it is, the perfect ending to what’s evolved (devolved?) into a perfect horror.

One final oddity about Stationfall is how little discussion the strange, creepy, off-putting experience it morphs into has prompted. Janet Murray, the MIT and Georgia Tech professor who’s largely responsible for Planetfall‘s reputation in academia thanks to writing about it in her seminal book Hamlet on the Holodeck, appears not to even be aware of this second and final chapter to Floyd’s story. Most contemporary reviewers in the trade press likewise never hinted at the darkness that eventually envelops the game, probably because, pressed for time as always, they never got that far. Indeed, Stationfall must be the perfect test to see if reviewers have really played the game they write about. Only Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia, although most interested as usual in giving puzzle hints, noted in passing that “there is one aspect of the ending that may give some people trouble.”

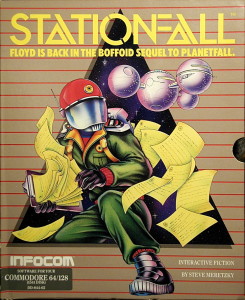

A subversive nightmare slipped into the garb of a middling fan-servicing sequel, Stationfall is in its way one of the most fascinating games Infocom ever published, evidence of a determination to keep challenging players’ expectations even as the curtain began to lower. In forcing you to kill Floyd, that most beloved personification of Infocom’s art, is Steve Meretzky making a statement about what the world was doing to Infocom through its increasing disinterest? That’s perhaps a stretch. Is the final effect Stationfall has on the player planned or accidental? That’s also difficult to know. All I can say is that it creeps me the hell out while still managing to be a superbly crafted traditional text adventure. I for one find it far more unnerving than Infocom’s ostensible first horror offering, The Lurking Horror, which was ironically released simultaneously with this game. Who would have guessed that Steve Meretzky could do scary this well? Who would have guessed from reading the box of Stationfall — “Floyd is back in the boffoid sequel to Planetfall.”; “The puzzles will challenge your intellect, the humor will keep you laughing, and Floyd will win your heart.” — that you’d end up creeping around the deserted station feeling like this? Many a horror movie starts under similarly innocuous circumstances, but the effect is lessened by the fact that the audience knows what they’ve signed up for, knows they just bought tickets to a scary movie. The question for them isn’t whether things will go south, but when. Playing Stationfall unspoiled for the first time is like walking into a Ghostbusters film that turns halfway through into the The Exorcist. A bait and switch? Perhaps, but a brilliantly effective one. Like, come to think of, much of Steve Meretzky’s career.

Duncan Stevens

September 10, 2015 at 3:00 pm

is Steve Meretzky making a statement about what the world was doing to Infocom through its increasing disinterest? That’s perhaps a stretch.

Or what he thought Activision was doing to Infocom? Probably still a stretch, but maybe less of one.

Jimmy Maher

September 11, 2015 at 5:56 am

That doesn’t quite fit with the timeline. Meretzky would have started this game in late 1986, when Jim Levy was still in control and relations were still fairly peachy. Even at the time of its release, it was just starting to become really clear to Infocom that life under Bruce Davis wasn’t going to be pleasant.

Marshal Tenner Winter

September 10, 2015 at 4:19 pm

“arguably more effective in its easy-going way than A Mind Forever Voyaging‘s more hectoringt tone” You may want to take off that superfluous T on “hectoring”.

David Welbourn

September 10, 2015 at 8:58 pm

There’s never a t-remover around when you need one.

Lisa H.

September 12, 2015 at 4:25 am

*rimshot*

Jimmy Maher

September 11, 2015 at 5:53 am

Thanks! And David — :).

_RGTech

June 29, 2024 at 5:37 pm

We’ve got another stray “t” in “Meretzkty”. It’s more subtle, therefore unidentified until now, but this can’t last forever :)

Jimmy Maher

June 30, 2024 at 8:44 am

That name will be the death of me. Thanks!

Bumvelcrow

September 10, 2015 at 7:56 pm

I’m glad it’s not just me who considers Stationfall one of the most atmospheric and disturbing games ever written! Reading this article brings back ancient memories of playing it and makes me want to shiver…

johannes_paulsen

September 12, 2015 at 12:09 am

I actually didn’t think killing Floyd was the most disturbing part of the game. That made sense — Floyd was being influenced by the pyramids, and he wasn’t in control of his decisions anymore, and if there was a way to save him, great, but I wasn’t as broken up by his death as I was in Planetfall. (It was easier to drop him since he was fighting me by that point anyway.)

No, the spookiest part was the fact that the malevolent alien presence that was just beneath the surface. The weird alien written language that involved tasting…. And those spooky pyramids. The most chilling part? The note in the bio lab that explained that the pyramids were like a “bacterioph-” For some reason, that stayed with me. I think I had to step away from the game for a little bit after reading that note!

Bob Reeves

September 13, 2015 at 1:39 pm

Since you’re the only human on the station at the end, there’s no one to repair Floyd. Plus, he’s probably suffered so much corruption from the virus that he’s past the point of no return–even if he could be repaired, he’d still be evil. I didn’t see Oliver as a replacement at all, just as an image of innocence that helps us remember Floyd as he was and can never be again. As to Meretzky being able to do scary, the 2081 sequence in AMFV gave me more nightmares than anything in Stationfall. Only the Vildroid chapter of The Space Bar is worse.

Jimmy Maher

September 14, 2015 at 5:48 am

While I’m not hugely invested in splitting hairs on this topic, I will just note neither of those explanations for Floyd’s irreversible death do it for me. Why can’t I just put him in my space truck and take him back to my ship to be repaired? And, even overlooking the fact that the old Floyd returned just before his death, why should Floyd remain evil when all of the other systems on the station, who were actually exposed to the virus for much longer, go back to normal?

Bob Reeves

September 14, 2015 at 1:09 pm

Oops. You’re right of course. I don’t think sometimes.

TsuDhoNimh

September 14, 2015 at 1:45 am

I have to admit that I played this game entirely because it was recommended here, got to the explosive series of puzzles, and got so fed up with doing that puzzle that I gave up. I think I restarted almost from the beginning three times because the explosive evaporated while I was fiddling with the timers and detonators or I’d set it up correctly but hadn’t yet figured out that the detonator was bad, which could have been clued a bit better than it was.

Not to mention the truly evil return of the demagnetized ID card “puzzle”.

Jimmy Maher

September 14, 2015 at 5:53 am

Hmm. I agree about the key card, which is an unnecessary cruel gotcha of the sort more typical of Sierra than late-era Infocom. The explosive, however, I thought to be a superb puzzle, if one that does indeed require some learning through failure. The tag on the explosive does tell you that it won’t last long in warmer temperatures — a way for Meretzky to say, “You might want to save here,” which is a kindness few other 1980s game designers would have bothered with.

TsuDhoNimh

September 15, 2015 at 6:37 pm

I suppose that one of the problems of playing old games is that I lack the patience for them that I had when I was twelve years old and the game I was playing was the only game around to play. So instead of playing a game like Stationfall all the way through, I get stuck about halfway through, give up, read the walkthrough (or Digital Antiquarian article) and I’m done.

Janice M. Eisen

September 14, 2015 at 11:11 am

I had thought that the sudden appearance of a younger-seeming robot named Oliver at the end was a reference to Cousin Oliver from The Brady Bunch, already a well-known cliche at the time. I guess only Meretzky would know for sure.

Stopin

September 19, 2015 at 1:56 pm

Stationfall won a place in my heart as the first Infocom game I finished without hints. The only other thing I remember is the steaming cup of coffee that suddenly appears in the mess hall. The whole thing was genuinely eerie and I just left it there. If I remember right, the game keeps listing it in the location description, slowly getting colder and colder.

Peter Piers

September 20, 2015 at 2:02 pm

I just picked up on something you said: “Meretzky’s sixth and, as it would transpire, final all-text adventure game”…

Are you not counting the Spellcasting 101 series on account of its graphics? Because, although they do add a lot to the experience, I think they’re more illustrative (think Scott Adams’ SAGA) than part of the actual game (think Sierra’s Illustrated Adventures). In fact, for most Legend Entertainment games (BTW, I’m really looking forward to you tackling LE!), I think you can turn off the graphics altogether.

Jimmy Maher

September 20, 2015 at 2:20 pm

By all-text I mean just that. I normally called interactive fictions with pictures illustrated text adventures to distinguish them from point-and-clickers and animated graphic adventures of the Sierra AGI style. That said, Meretzky actually did one more game for Infocom before Legend, Zork Zero, which doesn’t use graphics for illustrations so much as to help visualize certain puzzles.

Peter Piers

September 20, 2015 at 2:07 pm

(BTW, I always imagine Floyd as Bender from Futurama. *Always*. No, I have no idea why; I don’t see Bender as cute in any way, shape or form)

Scott Hughes

January 21, 2021 at 12:44 pm

That’s really funny. I played both Planetfall and Stationfall around the time Stationfall came out in the 80s, way before Bender existed. But I distinctly remember thinking when I started watching Futurama that Bender was essentially a grown-up Floyd, who turned out to be kind of a jerk. I think part of is that Bender opens up his chest and takes out booze; that reminded me of finding things stored inside Floyd.

Martin

August 23, 2016 at 1:23 am

Is it possible that you are over thinking the end of the game. Isn’t it just a rerun of Old Yeller. Maybe Floyd is undescribed but he’s (he?) really an electronic dog -as in mans best friend.

Wolfeye M.

September 19, 2019 at 11:15 am

I would have been so pissed at the end of Stationfall if I had played the game, especially after the boxart hyped it up as another fun adventure with Floyd. I hate Old Yeller type of stories.

I wonder, did Infocom get any angry letters about the ending? That was the era before Twitter, when companies and developers were just a few clicks away on social media. If someone bothered to send snail mail, they were probably genuinely upset.

Aaron

April 20, 2020 at 4:39 pm

I love these write-ups; thanks. BUT… please edit to add the spoiler alert earlier in the article before mentioning Floyd’s death!

Jimmy Maher

April 22, 2020 at 8:49 am

While I’m not insensitive to such things, Floyd’s death is so well-known by this point that it’s bit like “revealing” that everybody dies at the end of Hamlet. (Floyd’s death is easily the most celebrated and discussed single moment in the entire Infocom canon.) In any event, it’s probably good policy not to read a review of a sequel to a game if one is super-sensitive to spoilers of its predecessor; setting up the sequel kind of requires revealing at least some of what came before.

John Harris

April 30, 2022 at 4:26 pm

The note about the Infocom games being available on iOS seems almost cruel now that most of the App Store games from 2015 are unplayable now.

Ben

January 8, 2023 at 2:48 pm

others parts -> others

so maddenly so -> so maddeningly

juxtoposes -> juxtaposes

Jimmy Maher

January 10, 2023 at 8:41 am

Thanks!