One of the generation of male writers forged in the crucible of World War II, James Clavell had a much harder war of it than such peers as Norman Mailer, James Jones, Herman Wouk, Gore Vidal, J.D. Salinger, and James Michener. As a young man of barely twenty years, he found himself facing the Japanese onslaught on the Malay Peninsula at the onset of hostilities in the Pacific Theater. Following the most humiliating British defeat of the entire war, he spent the next three and a half years in prisoner-of-war camps, watching as more than nine out of every ten of his fellow soldiers succumbed to malnutrition, disease, and random acts of violence. Somehow he survived it all and made it home.

In 1953, he emigrated from his native England to Hollywood in the hope of becoming a film director, despite knowing only as much about how movies were made as his actress wife had deigned to tell him. He gradually established himself there as a director and screenwriter by dint of pluck and sheer stubbornness. Clavell claimed he learned how to write stories with mass appeal in Hollywood, developing a style that would preclude more than the merest flirtations with the sort of literary respectability enjoyed by the list of names that opened this article. To hear him tell it, that was just fine with him: “The first time you write a novel you go into ecstasy with the purple prose — how the clouds look, what the sunset is like. All bullshit. What happens? Who does what to whom? That’s all you need.”

If one James Clavell novel was going to please serious students of the literary arts, it would have to be his first, a very personal book in comparison to the epic doorstops for which he would later become known. Holding true to the old adage that everyone’s first novel is autobiographical, King Rat was a lightly fictionalized account of Clavell’s grim experience as a prisoner-of-war. Published in 1962, its success, combined with his difficulty finding sufficient screenwriting gigs, led him to gradually shift his focus from screenplays to novels. The next book he wrote, Tai-Pan (1966), was a much longer, more impersonal, wider-angle historical novel of the early years of Hong Kong. Four similar epics would follow at widely spaced intervals over the next thirty years or so, all chronicling the experiences of Westerners in the Asia of various historical epochs.

James Clavell’s fiction was in many ways no more thoughtful than the majority of the books clogging up the airport bestseller racks then and now. His were novels of adventure, excitement, and titillation, not introspection. Yet there is one aspect of his work that still stands out as surprising, even a little noble. Despite the three and a half years of torture and privation he had endured at the hands of his Japanese captors, he was genuinely fascinated by Asian and especially Japanese culture and history; one might even say he came to love it. And nowhere was that love more evident than in Clavell’s third novel, his most popular of all and the one that most of his fans agree stands as his best: 1975’s Shogun.

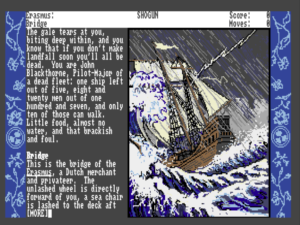

The star of Shogun is a typical Clavell hero, a Capable Man whose inner life doesn’t seem to run much deeper than loving queen and country and hating Papists. John Blackthorne is the English pilot — i.e., navigator — of the Erasmus, the first Dutch vessel to discover Japan, circa 1600. Unfortunately, the Spanish and Portuguese are already there when the Erasmus arrives, a situation from which will spring much of the drama of this very lengthy tale of 1100-plus pages. Blackthorne becomes Clavell’s reader surrogate, our window into the strangeness, wonder, mystery, and beauty of feudal Japan.

While Blackthorne’s adventures in Japan are (very) roughly based on those of an actual English adventurer named William Adams, Clavell plays up the violence and the sex for all its worth. Many a youthful reader went to bed at night dreaming fever dreams of inscrutable and lovely geishas and the boxes of toys they kept to hand: “The beads are carefully placed in the back passage and then, at the moment of the Clouds and the Rain, the beads are pulled out slowly, one by one.” Read by adults, such passages… er, extracts are still riotously entertaining in the way that only truly committed Bad Writing can be. My wife Dorte and I used Shogun as our bedtime reading recently. While it didn’t do much to encourage conjugal sexy times, it certainly did make us laugh; Dorte still thinks “pillowing,” Shogun‘s favorite Japanese euphemism for sex, is unaccountably hilarious, and is forever going on about pillowing this and pillowing that. (She also loves the notion of a “poop deck,” but I suppose I can’t blame Clavell for that.)

Unsubtle prose and dodgy euphemisms aside, the first 25 to 30 percent of Shogun is by far the most compelling. Long enough to form a novel of reasonable length in their own right, the early chapters detail the arrival of Blackthorne and his Dutch cohorts in Japan, upon whose shores they literally wash up, starving and demoralized after their long voyage across the Pacific. I’ve occasionally heard the beginning of Shogun described as one of the finest stories of first contact between two alien cultures ever written, worthy of careful study by any science-fiction author who proposes to tell of a meeting between even more far-flung cultures than those of Europe and Japan. To that suggestion I can only heartily concur. As Blackthorne and his cohorts pass from honored guests to condemned prisoners and back again, struggling all the while to figure out what these people want from them, what they want from each other, and how to communicate at all, the story is compulsively readable, the tension at times nearly unbearable. (One suspects that some of the most horrific scenes, like the ones after Blackthorne and the crew are cast into a tiny hole and left to languish there in sweltering heat and their own bodily filth, once again draw from Clavell’s own prisoner-of-war experiences.) While I admit to being far from intimately familiar with the whole of the James Clavell oeuvre, I’d be very surprised if he ever wrote anything better than this.

After Blackthorne, stalwart Capable Man that he is, manages to negotiate a reprieve for the crew and a place for himself as a trusted advisor to a powerful daimyo named Toranaga, the book takes on a different, to my mind less satisfying character. It ceases to focus so much on Blackthorne’s personal plight as a stranger in a strange land in favor of a struggle for control of the entire country, once again based loosely on actual history, that is taking place between Toranaga, very broadly speaking the good guy (or at least the one with whom our hero Blackthorne allies himself), and another daimyo named Ishido. At the same time, the Portuguese Jesuits are trying to stake out a space in the middle that will preserve their influence regardless of who wins, whilst also working righteously to find some way to do away with Blackthorne and the Dutch sailors, who if allowed to return to Europe with information on exactly where Japan lies represent an existential threat to everything they’ve built there. Plot piles on counter-plot on conspiracy on counter-conspiracy, interspersed with regular action-movie set-pieces, as all of the various factions maneuver toward the inevitable civil war that will decide the fate of all Japan for decades or centuries to come.

In the meantime, Blackthorne, apparently deciding his life isn’t already dangerous enough, is carrying on an illicit romance with the beautiful Mariko, wife of one of Toranaga’s most highly placed samurai. Their relationship was much discussed in Shogun‘s first bloom of popularity as being the key to the book’s considerable attraction for female readers; very unusually for such a two-fisted tale of war, adventure, and history, Shogun supposedly enjoyed more female readers than male. True to Clavell’s roots, however, Blackthorne and Mariko’s is a depressingly conventional Hollywood romance. We’re expected to believe that these two characters are wildly, passionately in love with one another simply because Clavell tells us they are, according to the Hollywood logic that two attractive people of the opposite sex thrown into proximity with one another must automatically fall in love — and of course lots of sex must follow.

The plot continues to grow ever more byzantine as the remaining page-count dwindles, and one goes from wondering how Clavell is ever going to wrap all this up to checking Amazon to be sure there isn’t a direct sequel. And then it all just… stops, leaving more loose threads dangling than my most raggedy tee-shirt. I’ve read many books with unsatisfying endings, but I don’t know if I’ve ever read an ending as half-baked as this one. It’s all finally come down to the war that’s been looming throughout the previous 1100-plus pages. We’re all ready for the bloody climax. Instead Clavell gives us a three-page summary of what might have happened next if he’d actually bothered to write it. It’s for all the world like Clavell, who admitted that he wrote his novels with no plan whatsoever, simply got tired of this one, decided 1100 pages was more than enough and just stopped in medias res. Shogun manages the feat, perhaps unique in the annals of anticlimax, of feeling massively bloated and half-finished at the same time. This is a Lord of the Rings that ends just as Frodo and Sam arrive in Mordor; a Tale of Two Cities that ends just as Carton is about to make his final sacrifice. I’ve never felt so duped by a book as this one.

But I must admit that I seem to be the exception here. Whether because of the masterfully taut beginning of the story, the torrid love affair, or the lurid portrayal of Japanese culture that pokes always through the tangled edifice of plot, few readers then or now seem to share my reservations. Shogun became an instant bestseller. In 1980, a television miniseries of the book was aired in five parts, filling more than nine hours sans commercials. It became the most-watched show ever aired on NBC and the second most popular in the history of American television, its numbers exceeded only by those of Roots, another miniseries event which had aired on ABC in 1977. When many people think of Blackthorne today, they still picture Richard Chamberlain, the dashing actor who played him on television. Together the book and the miniseries ignited a craze for Japanese culture in the West that, however distorted or exaggerated it may have been, did serve as a useful counterbalance to lingering resentments over World War II and, increasingly, fears that Japan’s exploding technological and industrial base was about to usurp the United States’s place at the head of the world’s economy.

At this point, at last, Shogun‘s huge popularity on page and screen brings us in our roundabout way to Infocom — or, more accurately, to their corporate masters Mediagenic. [1]Mediagenic was known as Activision until mid-1988. To avoid confusion, I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article. (If the preface to the real point of this article seemed crazily extended, I can only plead that, with Shogun the game having little identity of its own apart from the novel on which it’s based, it’s hard to discuss it through any other framework.)

Mediagenic’s absolute mania for licensed games following the accession of Bruce Davis to the CEO’s chair has been well-established in other articles by now. Infocom was able to find some excuse to head off most of the ideas in that vein that Mediagenic proposed, but Shogun was an exception. When Mediagenic came to Infocom with a signed deal already in place in late 1987 to base a game on this literary property — from Bruce Davis’s perspective, the idea was right in Infocom’s wheelhouse — their problem child of a subsidiary just wasn’t in any position to say no. Dave Lebling, having recently finished The Lurking Horror and being without an active project, drew the short straw.

Shogun the game was a misbegotten, unloved project from the start, a project for which absolutely no one in the Infocom, Mediagenic, or Clavell camps had the slightest creative passion. The deal had been done entirely by Clavell’s agent; the author seemed barely aware of the project’s existence, and seemed to care about it still less. It was a weird choice even in the terms of dollars and cents upon which Bruce Davis was always so fixated. Yes, Shogun had been massively popular on page and screen years earlier, and still generated strong catalog sales every year. It was hard to imagine, however, that there was a huge crowd of computer gamers dying to relive the adventures of John Blackthorne interactively. Why this of all licenses? Why now?

Dave Lebling was duly dispatched to visit Clavell for a few days at his chalet in the Swiss Alps to discuss ideas for the adaptation; he got barely more than a few words of greeting out of the man. His written requests for guidance were answered with the blunt reply that Clavell had written the book more than a decade ago and didn’t remember that much about it; the subtext was that he couldn’t be bothered with any of it, that to him Lebling’s game represented just another check arranged by his agent. Lebling was left entirely on his own to adapt another author’s work, with no idea of where the boundaries to his own creative empowerment might lie. In the past, Infocom had always taken care to avoid just this sort of collaboration-in-name-only. Now they’d had it imposed upon them.

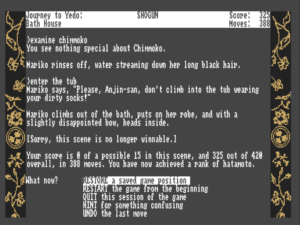

Lebling chose to structure his version of Shogun as a series of Reader’s Digest “scenes from” the novel, cutting and pasting unwieldy chunks of Clavell’s prose into the game and demanding that the player respond by doing exactly what Blackthorne did in the novel in order to advance to the next canned scene. The player who has read the novel will find little interest or challenge in pantomiming her way through a re-creation of same, while the player who hasn’t will have no idea whatsoever what’s expected of her at any given juncture. It’s peculiar to see such a threadbare design from a company as serious about the craft of interactive fiction as Infocom had always been. Everyone there, not least Lebling himself, understood all too well the problems inherent in this approach to adaptation; these very same problems were the main reason Infocom had so steadfastly avoided literary licenses that didn’t come with their authors attached in earlier years. One can only presume that Lebling, unsure of how far his creative license extended and bored to death with the whole project anyway, either couldn’t come up with anything better or just couldn’t be bothered to try.

Shogun includes one graphical puzzle reminiscent of those in Zork Zero, a maze representing the tangled alleys of Osaka.

Consider the game’s handling of an early scene from the novel: the first time Blackthorne meets Yabu and Omi, respectively the daimyo and his samurai henchman who have dominion over Anjiro, the small fishing village where the Erasmus has washed up. Also present as translator is a Portuguese priest, Blackthorne’s sworn enemy, who would like nothing better than to see him condemned and executed on the spot. In the book, Blackthorne’s observations of the priest’s interactions with the two samurai convince him that there is no love lost between him and them, that Yabu and Omi hate and mistrust the priest almost as much as Blackthorne does. Blackthorne wants to communicate that he shares their sentiment, but of course all of his words are being translated into Japanese by the priest himself — obviously a highly unreliable means of communication in this situation. Desperate to show his captors that he’s different from this other foreigner, he lunges at the priest, grabs his crucifix, and breaks it in two, a deadly sin for a Catholic but a good day’s work for a Protestant like him. Yabu and especially Omi are left curious and more than a little impressed; Blackthorne’s action quite possibly staves off his imminent execution.

In the book, this all hangs together well enough, based on what we know and what we soon learn of the personalities, histories, and cultures involved. But for the game to expect the player to come up with such a seemingly random action as lunging for the crucifix and breaking it is asking an awful lot of anyone unfamiliar with the novel. It’s not impossible to imagine the uninitiated player eventually coming up with it on her own, especially as Lebling is good enough to drop some subtle hints about the crucifix “on its long chain waving mockingly before your face,” but she’ll likely do so only by dying and restoring many times.

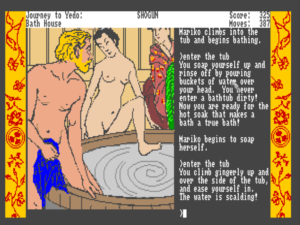

Shogun is the only Infocom game outside of Leather Goddesses of Phobos in which you have to “make love to” someone — or type another euphemism, if you like — in order to score points. (Unfortunately, you can’t use “pillow” as a verb. This Dorte finds deeply disappointing.) It’s also, needless to say, the only one with nudity. Too bad Blackthorne is covering up his manly member, whose size is a constant point of discussion in the book.

And this is far from the worst of Lebling’s “read James Clavell’s mind” moments. In their announcement of the game in their newsletter, Infocom noted that “the key to success in the interactive Shogun is the ability to act as the British pilot-major Blackthorne would.” For the player who hasn’t read the book and thus doesn’t know Blackthorne, this is quite a confusing proposition. For the player who has, the game falls into a rote pattern. Remember (or look up) what Blackthorne did in the book, figure out how and when to phrase it to the parser, and you get some points and get to live a little longer. Do anything else, and you die or get a message saying “this scene is no longer winnable” and get to try again. In between, you do a lot of waiting and examining, and lots of reading of textual cut scenes — called “interludes” by the game — that grow steadily lengthier as the story progresses and Blackthorne’s part in it becomes more and more ancillary.

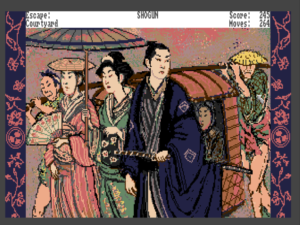

In a telling indication of how the times had changed for Infocom, by far the most impressive aspect of Shogun is its visual presentation. Promoted, like the earlier Zork Zero, as “graphical interactive fiction,” it and the simultaneously released Journey are the first Infocom games to unabashedly indulge in pictures for their own sake, abandoning Steve Meretzky’s insistence that his game’s graphics always serve a practical gameplay function. Shogun‘s pictures, drawn in the style of classical Japanese woodcuts by Donald Langosy, are lovely to look at and perfectly suit the atmosphere of the novel. The game’s one truly innovative aspect is the same pictures’ presentation onscreen. Rather than being displayed in a static window, they’re scattered around and within the scrolling text in various positions, giving the game the look of an unfurling illustrated scroll. Infocom had had their share of trouble figuring out the graphics thing, but Shogun demonstrates that, clever bunch that they were, they were learning quickly. Already Infocom’s visual palette was far more sophisticated than that of competitors like Magnetic Scrolls and Level 9 who had been doing text adventures with pictures for years. Pity they wouldn’t have much more time to experiment.

“The socks stay on, Mariko!” [2]Al and Peg

But of course, as Infocom’s vintage advertisements loved to tell us, visuals alone do not a great game make. Shogun stands today as the most unloved and unlovable of all Infocom’s games, a soulless exercise in pure commerce that didn’t make a whole lot of sense even on that basis. Released in March of 1989, its sales were, like those of all of this final run of graphical games, minuscule. In my opinion and, I would venture, that of a substantial number of others, it represents the absolute nadir of Infocom’s 35-game catalog. It is, needless to say, the merest footnote to the bestselling catalog of James Clavell, who died in 1994. And, indeed, it’s little more worthy of discussion in the context of Infocom’s history; the words I’ve devoted to it already are far more than it deserves. I have two more Infocom games to discuss in future articles, each with problems of their own, but we can take consolation in one thing: it will never, ever get as bad as this again. This, my friends, is what the bottom of the barrel looks like.

(Sources: As usual with my Infocom articles, much of this one is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Some of it is also drawn from Jason’s “Infocom Cabinet” of vintage documents. And the very last issue of Infocom’s The Status Line newsletter, from Spring 1989.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Mediagenic was known as Activision until mid-1988. To avoid confusion, I just stick with the name “Mediagenic” in this article. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Al and Peg |

Pedro Timóteo

July 7, 2016 at 4:57 pm

First, great as always. :)

Second, yes, the novel (which I have read several times, and also listened to the excellent audiobook)’s end is quite abrupt and disappointing, but I still love the book and would recommend it to anyone. The problem with writing about the war is that it would add more years to the story, and Blackthorne would be little more than an observer (which was already happening to a degree near the end of the book).

Third, a typo: “diamyo” should be “daimyo”. Look for it at least 3 times. :)

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 7:45 am

Thanks!

djogo patrao

July 7, 2016 at 5:05 pm

Great article, as always! I actually liked the book and didn’t missed a “big ending” – although by hollywood standards it should have one. For me, the overall strategy of Toranaga is the most compelling aspect of the book.

Btw , I think “diamyo” should be “daimyo”.

Thanks!

Duncan Stevens

July 7, 2016 at 5:26 pm

I read the book as a kid, a very long time ago, and I don’t recall the non-ending for some reason. (I do remember snickering at the euphemisms for sex and anatomy, though.)

I never played the game, and even if I were inclined to, it’s…rather hard to find now. (Indeed, I’m curious about how you managed to get a copy.) I hope you had fun laughing at it, even if that’s not the usual Infocom experience.

Marcus Johnson

July 7, 2016 at 7:54 pm

You can play the DOS version in your browser at the Internet Archive:

https://archive.org/details/msdos_James_Clavells_Shogun_1988

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 7:49 am

Like a lot of the stuff I play and write about, my source was not, strictly speaking, legal. ;) It’s available on lots of the abandonware archives, including even archive.org. I did make the mistake of buying Shogun for my Amiga back in the day — one of a bare handful of thousands who did so — so I figure I’m ethically covered.

Pedro Timóteo

July 8, 2016 at 9:27 am

Yes, I don’t think you can get Shogun legally these days, except perhaps buying it second-hand on eBay.

Personally, I have no qualms about “abandonwaring” a game that absolutely isn’t available for sale, but opinions may vary. :)

Matthew Heiti

July 7, 2016 at 5:30 pm

Excellent article! I remember that book looming on the shelf at home. I never did read it and opted for the equally lenghty Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa.

Might be of interest to you that there was actually another computer game released based on this book in 1986 (link to the lemon page here – http://www.lemon64.com/games/details.php?ID=2300)

I owned this Mastertronic version for the C64 growing up. It was a lovely game; a little pocket universe of tactics, alliances, betrayal and negotiation.

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 7:52 am

Yeah, I did discover that and thought about trying to work it in, but it would have ruined the article’s flow and didn’t seem all that ultimately important to the Infocom game. Thanks for mentioning it here, though! I have no personal experience with it, but it sounds like it was more interesting than the Infocom game.

Andrew Plotkin

July 7, 2016 at 5:38 pm

It’s worth talking about the availability issue, actually. HHGG and Shogun are the two Infocom parser games that completely vanished from Activision’s catalog after the LTOI era (1992). HHGG reappeared on Douglas Adams’ personal web site, and Shogun was just gone.

Because of this, we’ve always assumed that the copyrights of those games were handed over to the titular authors. (And that Adams was much happier with his game than Clavell, or Clavell’s estate, was about his.) But this has only ever been an assumption.

In your researches, have you come across anything to confirm or deny this?

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 7:55 am

I know that in the case of Douglas Adams the game reverted to him after a certain window of time, probably ten years. His estate, as you noted, later began to license it to the BBC, making it the easiest of all Infocom games for the casual player to access today. Circumstantial evidence would indicate that Shogun had the same deal, but, it being a bad game of no commercial value whatsoever, the Clavell estate may not even know they own it.

Merman

July 7, 2016 at 5:40 pm

It is also worth mentioning the other Shogun game based on the novel, created by Virgin Games.

http://www.gb64.com/game.php?id=6777&d=18&h=0

This is an arcade adventure, with the player choosing a character type and then exploring stylised areas to gain allies, fight enemies and earn enough respect to be made Shogun.

James Clavell’s Tai-Pan also inspired an 8-bit game.

Pedro Timóteo

July 8, 2016 at 9:24 am

James Clavell’s Tai-Pan also inspired an 8-bit game.

Yes. Interestingly, the closest thing to Sid Meier’s Pirates! on the Spectrum. Decent game (with great graphics and music for the time), but it had a big problem, IMO: when in town, instead of picking options from a menu, you had to walk through the maze-like streets, which mostly looked the same, and each town had a *different* map (generated from a seed, so it didn’t change from game to game). It quickly became *quite* boring, especially at the beginning of the game, where you had to walk around press-ganging drunken citizens until you filled your crew.

The mini-games were far more action-oriented than Pirates!’s (including one that was basically a Gauntlet clone), but also quite harder.

Pity the Spectrum (which I had back then) never got Pirates!. The Amstrad CPC did, but it was a very poor port of the C64 original, including automatically converted graphics, and playing much slower…

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 10:33 am

Another version of Tai-Pan was quite popular on the Apple II in the early days: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taipan!/. Given the nature of the industry at the time, I would guess it to have been unlicensed. I’ve often suspected it to have been an influence on Elite and later Pirates!, but, given I’ve never found any hard evidence to back up my suspicion, never wrote that in the articles on those games.

Pedro Timóteo

July 11, 2016 at 2:09 pm

I found out about that when, some >10 years ago, I was experimenting with an Apple II emulator and trying out its games (as, being Portuguese, I never even saw a physical Apple II in front of me, although my stepmother (a teacher) once mentioned her school having at least a single IIc). I tried out that game wondering if it was a port of the 1987 game, in fact. It wasn’t, of course.

By the way, apparently your WordPress removed the exclamation mark from the end of the URL in your comment above, so it’s now pointing to the wrong Wikipedia article.

Jimmy Maher

July 11, 2016 at 2:27 pm

Thanks! Should be fixed now.

Captain Rufus

July 7, 2016 at 7:14 pm

Oddly enough there is also a C64 action adventure game based on the book that came out roughly at the same time.

Lisa H.

July 7, 2016 at 7:36 pm

Do anything else, and you die or get a message saying “this scene is no longer winnable”

Wow. Disheartening, eh? Although I suppose I should be glad they saw fit to tell you outright, rather than leaving you to flounder.

Pedro Timóteo

July 7, 2016 at 9:16 pm

There’s a funny example in the last screenshot: don’t get in the bathtub with Mariko in time, the romance never begins… game over.

Jayle Enn

July 7, 2016 at 9:27 pm

…while the player who hasn’t will have no idea whatsoever what’s expected of her at any given juncture.

Oh god, that was me. I got through the first scene by using the hint system as a walkthrough, then… I think I got peed on by the Daimyo. Somewhere in there I realized that I was playing high-stakes mad-libs with a transcript and gave up on it. :(

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 7:59 am

For what it’s worth, you’re *supposed* to get peed on. Fail to do so (or, maybe better said, fail to have it done to you) and it’s game over again. Why? Because that’s what happened in the book, of course!

Kaitain

July 7, 2016 at 10:30 pm

Minor typo:

diamyo -> daimyo

I remember the Chamberlain series very well. It seemed very dark and violent for the time…no doubt would come across as being very tame stuff these days. Sean Connery was the producers’ first choice for the role of Blackthorne, but he wasn’t interested (or they didn’t offer enough).

Keith Palmer

July 8, 2016 at 12:03 am

Knowing we’d get to this game in time, and fully aware of the old dismissals of it (it is sort of interesting to know just how it began at last; I might have supposed Infocom was “scraping on its own for something that might be successful by that point”), I found and read an old copy of the novel not that long ago. I did muse a bit about the ambiguous fate a certain number of “best-sellers” seem to reach sooner or later (I do seem to put Herman Wouk’s roughly contemporaneous The Winds of War in the same category and might even have been a bit surprised to see him in the opening list; I suppose The Caine Mutiny could be invoked to correct me). All the same, I still seemed to plug through the pages with dispatch. (The only problem there is how often I wonder these days if I’m stuck thinking that if I don’t sweat and struggle to get through prose fiction, it must be “not worth the attention anyway…”) I certainly did wonder whether the character interaction was something that would “work” in interactive fiction; the early part of the novel, with the language barriers in place, might have seemed more interesting that way.

So far as the ending goes anyway, I suppose I was simply surprised; not seeming to recognize the name “Toranaga,” I supposed the protagonists had to be on the losing side. It took finishing the novel to realise it was a “all the characters have slightly different names from their historical inspirations” deal.

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 8:10 am

By coincidence, I’m actually reading The Caine Mutiny right now and enjoying the hell out of it. Is Herman Wouk not in literary fashion anymore? I’d never read him before. The Winds of War and War and Remembrance aren’t the sort of thing I usually go for anymore — as a kid I remember looking at them hard, but, little warmonger that I was, I wanted lots of combat action, and they seemed full of too much family/relationship stuff — but I was thinking about giving them a go at some point based on how good The Caine Mutiny is.

Michener is the most interesting figure on that list in terms of literary respectability. Once considered on a par with writers like Vidal and Mailer when his first book won the Pulitzer Prize, he pissed all his literary respectability away to start writing all those workmanlike historical doorstops. In compensation, he did sell 75 to 100 million books in his lifetime, which I’m sure helped to ease some of the pain of the critics’ sneers.

Duncan Stevens

July 8, 2016 at 4:29 pm

I haven’t read Caine Mutiny, but both Winds of War and War and Remembrance are…not bad, once you accept that members of a specific family just happen to be in so many key places over the course of the war. The prose occasionally veers toward the purple, as I recall, but only occasionally. (I read them quite a while ago, but I was old enough that I’d have put down badly-written stuff of that length.) One device I found particularly interesting in the second one is that the action is intercut with a (fictional) German general’s dissenting view on why the war played out as it did.

Keith Palmer

July 8, 2016 at 4:47 pm

Maybe that’s a fair enough summary of Winds of War/War and Remembrance. I can’t say I “disliked” them (the General’s commentary was also an interesting part of them to me), but perhaps my feeling was that as a sort of “everything in World War II fit into one fictional narrative” work, it was somehow “less profound” than a more focused novel (like The Caine Mutiny). This, though, might be a matter of “trying to present a personal reaction as a definitive judgment…”

Alexander Freeman

July 8, 2016 at 3:34 am

“James Clavell’s fiction was in many ways no more thoughtful than the majority of the books clogging up the airport bestseller racks then and now…

Read by adults, such passages… er, extracts are still riotously entertaining in the way that only truly committed Bad Writing can be.

And then it all just… stops, leaving more loose threads dangling than my most raggedy tee-shirt. I’ve read many books with unsatisfying endings, but I’ve never read an ending quite as half-assed as this one. It’s all finally come down to the war that’s been looming throughout the previous 1100-plus pages. We’re all ready for the bloody climax. Instead Clavell gives us a three-page summary of what might have happened next if he’d actually bothered to write it. It’s for all the world like Clavell, who admitted that he wrote his novels with no plan whatsoever, simply got tired of this one, decided 1100 pages was more than enough and just stopped in medias res…

His written requests for guidance were answered with the blunt reply that Clavell had written the book more than a decade ago and didn’t remember that much about it…”

Well, no wonder I’ve never heard anything about Clavell outside Shogun and Infocom! It sounds as though he was just some mediocre writer who didn’t take pride in his work.

“Shogun the game was a misbegotten, unloved project from the start, a project for which absolutely no one in the Infocom, Mediagenic, or Clavell camps had the slightest creative passion… It was hard to imagine, however, that there was a huge crowd of computer gamers dying to relive the adventures of John Blackthorne interactively. Why this of all licenses? Why now?”

That makes me wonder why Activision agreed to it.

“The game’s one truly innovative aspect is the same pictures’ presentation onscreen. Rather than being displayed in a static window, they’re scattered around and within the scrolling text in various positions, giving the game the look of an unfurling illustrated scroll.”

*Shrugs shoulders* Well, I dunno. I kind of like how a static window lets the picture remain on the screen. Maybe the “illustrated scroll” approach works better with the Japanese-style artwork here, but I don’t think it would work better with other illustrated games. The fact that Arthur took the static-window approach later makes me think Infocom thought the same way.

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 8:15 am

“Just some mediocre writer” is pretty harsh. There’s something in Clavell and especially Shogun to which a whole lot of people respond. I’m not one of those people — to me he *is* just a mediocre (at best) writer — but, hey, different strokes for different folks and all that.

Poddy

July 8, 2016 at 4:26 am

I remember Shogun fondly as one of those doorstops I lugged from class to class as an unloved teenager, and it had struck me as a really interesting First Contact story at the time.

Real question, though, are those illustrations actually considered nice by many people? I keep scrolling up to go look at naked Mariko because I am sure, deadly sure, that women’s legs don’t attach that way.

Lisa H.

July 8, 2016 at 5:40 am

*sings* “The left hip’s connected to the… right knee!”

Wait, that can’t be right…

Jimmy Maher

July 8, 2016 at 8:17 am

I think the pictures are deliberately stylized to resemble classical Japanese woodcuts. But, knowing nothing about classical Japanese woodcuts, I could be wrong.

Alexander Freeman

July 8, 2016 at 3:56 pm

There definitely supposed to look like that. In fact, this:

https://www.filfre.net/2016/07/shogun/james_clavells_shogun_r295_1988activision_001/

bears a passing resemblance to this:

http://blog.art.com/artwiki/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/hokusai-great-wave-at-kanagawa-japanese-artwork.png

Cliffy

October 7, 2016 at 6:41 pm

A few years back I saw an exhibition of that woodcut series, most of them early pressings (when printing off the woodcuts, the process would eventually damage the carving, so prints made earlier in the run have much sharper lines). Those things are no joke. If you ever get a chance to see an original print of the Great Wave at Kanagawa, **go**.

Duncan Stevens

July 8, 2016 at 4:12 pm

FYI, I’m no expert here, but a considerably better-written novel about the Dutch in Japan during the Edo period is David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet.

matt w

July 9, 2016 at 12:32 pm

It certainly is much better written, but I had problems with the idea that there was all this meticulously researched stuff and then the plot hinged on a pnaavonyvfgvp onol-zheqrevat frk fynir vzzbegnyvgl phyg (rot13 for extreme spoilage of the first degree), which as far as I can tell has no basis in fact whatsoever. Which is a problem both because it doesn’t fit well with the meticulously researched stuff and also because it comes across as pretty racist. Imagine if a similar plot were part of a historical novel about medieval Jewish communities.

Lisa H.

July 10, 2016 at 2:57 am

the plot hinged on a pnaavonyvfgvp onol-zheqrevat frk fynir vzzbegnyvgl phyg

Wow, what? Seriously?! Maybe I’m glad I haven’t played this game.

Pedro Timóteo

July 10, 2016 at 2:12 pm

Either I misunderstood something, or that had nothing to do with this game (and there’s certainly nothing like it in the Shogun novel)…

Jubal

July 11, 2016 at 12:55 am

The “frk fynir vzzbegnyvgl phyg” is in the David Mitchell novel mentioned in Duncan Stevens’ comment, not Shogun, which indeed features nothing of the sort.

Lisa H.

July 11, 2016 at 2:29 am

Ah, sorry, I did misunderstand. I subscribe to the comments feed, so I often read them out of direct context.

Duncan Stevens

July 11, 2016 at 2:04 pm

Imagine if a similar plot were part of a historical novel about medieval Jewish communities.

Then it would have set off a lot more alarms because it played to specific, tired anti-Semitic smears. The phyg in Thousand Autumns doesn’t reinforce any stereotype about Asian or Japanese people, at least not one I’d ever heard of. (And there are a lot of applicable stereotypes that the novel carefully avoids–the guy who looks like a white savior ends up not actually saving anyone, the apparently passive Asian female bails herself out of her exploitative situation, etc.) But I take your point about the strangeness of dropping a wholly invented idea into an otherwise carefully researched setting.

matt w

July 12, 2016 at 3:15 am

Isn’t Sinister Oriental Cult a pernicious stereotype about Asians?

More to the point, Mitchell can only get away with this and retain his critical respectability because of the foreignness of Japan to his audience. If he tried to write a meticulously researched book about the history of Christianity whose plot hinged on that sort of thing, the congoscenti would laugh at it the way they laughed at The Da Vinci Code.

Duncan Stevens

July 12, 2016 at 3:56 am

There are sinister cults the world over, many of them depicted in popular culture, so I’m going to go with “no.” Had Mitchell written a book about an evil exploitative cult in Texas, no one would have batted an eye.

I’m pretty sure people laugh at Dan Brown in large part because of his writing, and I think you may overstate the insistence on strict historical plausibility among literary critics. The Name of the Rose, for instance, has a fairly outlandish plot in a recognizable medieval Christian setting, but I don’t think critics scoff at it on that basis. (Yes, I know, it’s really all about semiotics, but still.)

Petter Sjölund

July 9, 2016 at 2:09 am

It’s more than twenty years since I played it, but I actually remember the beginning of the game, while you’re still on your ship, as pretty good for its time. How does it hold up?

Jimmy Maher

July 9, 2016 at 1:02 pm

The opening scene definitely is better than much of what follows. The game is more willing there to go after the spirit rather than the letter of the original story, using methods that work in an interactive context. Take, for instance, the Erasmus’s crew, whom Clavell in the novel establishes through lots of flashbacks, exposition, and dialog to be, one or two exceptions aside, a pretty craven, lazy, drunken, useless bunch. With far fewer words at his disposal, Lebling establishes the same thing by inserting a little mystery story of a puzzle involving Blackthorne’s last apple, which one of the crew has stolen. The way you wind up retrieving it does much to establish Blackthorne’s character as well as a two-fisted man of action, helping to set your expectations for what sort of actions the game is likely to consider appropriate for him. If there’d been more of that and less direct transcription of the novel’s events, Shogun would have been a much better game.

Petter Sjölund

July 9, 2016 at 11:38 pm

Yeah, that’s about what I remembered. I my memory it also has this nice atmosphere of being trapped in this ship, starving and lost at sea, that has no counterpart in the rest of the game.

On another note, some of the things you criticize this game of, such as the player pantomiming her way through a re-creation of the book, might apply to the Hitchhiker’s Guide game as well. When you think about it, large parts of the latter game are about methodically clueing you towards doing some pretty illogical things. Perhaps the difference between a terrible game and a great one sometimes only is the amount of time and polish spent on it.

Jimmy Maher

July 10, 2016 at 8:18 am

I don’t really see much comparison myself. While I suppose one could say that the first third to half of Hitchhiker’s does have you to some extent pantomiming your way through the book, that’s only in the broad strokes; it’s full of original puzzles and situations that work in the context of interactive fiction from the beginning. And then of course it diverges radically once you get to the Heart of Gold.

I wouldn’t even say that Shogun’s core problems have much to do with polish per se. Even at this late date and in this dispiriting atmosphere, Infocom’s text is still polished and copy-edited to a degree matched by no one else in the industry, and I never encountered anything that seemed like an outright bug. Shogun’s problems are down to something more fundamental than a lack of polishing.

Petter Sjölund

July 10, 2016 at 10:49 am

Well, it’s some time since I played them both, but I think there are some similarities. Hitchhiker’s doesn’t follow the book very closely, but there is a similar pattern of short, loosely connected scenes that you “win” by finding the right outlandish command to type. Sebz rawbl cbrgel naq jenc gur gbjry nebhaq zl urnq gb gnfgr qnexarff naq gnxr ab grn. Of course this is only part of Hitchhiker’s, and it has some great puzzles and writing. But it might have been something like that Lebling was aiming at.

matt w

July 11, 2016 at 10:37 am

I don’t think the last two you mentioned are even in the book, though.

Bumvelcrow

July 9, 2016 at 6:21 am

Whilst I wouldn’t argue that it’s not a great game, I do have good memories of the early parts, perhaps due to the way the graphics enhance the already tension-filled atmosphere generated by the text. After that it drifted and I lost interest but it had enough of an impact that it left me with a permanent interest in Japanese culture and even tried to learn the language. I don’t think I can say that about any other game. Well, other than Trinity – I think that helped turn me into a Physicist!

I did read the book, after the game, but remember very little of it after the early culture shock. I do tend to keep a mental list of bad endings I can repeatedly complain about, and Shogun isn’t on it so it can’t have been that bad. Or perhaps I’d just tuned out by then and was glad when it was over.

Brian Bagnall

July 10, 2016 at 4:42 pm

I have vague memories of seeing snippets of this miniseries when I was young and recall being horrified when a few crew-members were boiled alive. Then maybe 10 years ago in a fit of nostalgia revisiting miniseries like V and The Day After it got on my watch list. It was definitely good enough to hold my attention throughout the series, although Richard Chamberlain did seem a little miscast to me. Sean Connery certainly would have elevated this to new heights. I also ended up reading the book and being quite impressed with what he had created.

Game of Thrones seems to be hitting that same sweet spot for mass audiences that Shogun hit back then: a tapestry of characters spinning plots to rule the land, surprise deaths of established characters, lurid sex scenes and a world very alien from our own.

Pedro Timóteo

July 14, 2016 at 8:31 am

One more, I think:

Shouldn’t this be “ascension”?

Jimmy Maher

July 14, 2016 at 9:11 am

Either would work, but I like “accession” here. It’s usually used in relation to the coming of a king into his rightful power, and I think that kind of fits with the way Bruce Davis seemed to see himself and certainly the way that Infocom saw him. It’s a little cheeky, sure, but what the hell.

Pedro Timóteo

July 14, 2016 at 3:54 pm

Fair enough. I didn’t know this usage of “accession”, thanks. :)

Markus

July 18, 2016 at 11:08 am

Maybe tell Dorte that after reading this, I’m inspired to use “go pillow yourself” in conversation…

Cliffy

October 7, 2016 at 7:24 pm

When I learned via my purchase of Lost Treasures v. 2 in ’94 or thereabouts that Infocom had done a Shōgun adaptation after I’d lost track of them in the late ’80’s (just like everyone else), I thought it made perfect sense. While Shōgun might not have been a literary masterwork, on the basis of the miniseries it had a pedigree alongside that of Roots and Thornbirds — perhaps this wasn’t the stuff that they were talking about in university English departments, but within the popular mainstream it had an air of erudition and sophistication that seemed to me exactly the attitude Infocom had cultivated during its mid-’80’s heyday.

Of course, had I read the book, perhaps I would have recognized that this was an illusion. But most of the potential audience hadn’t read it, either — they just knew that it had been considered an important work, and the subject of plenty of water-cooler conversation, not all that long ago.

It’s too bad the circumstances of the game’s creation were so confining. But I think the idea of it was one of the few things Davis got right with the handling of Infocom. (And the artwork is lovely.)

David Lebling

May 2, 2025 at 9:17 pm

The artwork was done by Donald Langosy, and I totally agree that the artwork is lovely.

Busca

May 18, 2025 at 8:47 am

Since David ‘Dave’ Lebling apparently briefly showed up in person in the comments here now, maybe add he’s also been recently quoted with a few other comments about Shogun and its development in this article.

Through it I learned as well that Donald Langosy joined the project at the suggestion of his (Langosy’s) wife Elizabeth, a regular Infocom employee who worked on Infocomics games like the ZorkQuest series (in fact she was once mentioned by name when Jimmy briefly brought up the Infocomics games in this article about Infocom under Activision).

Aula

January 15, 2018 at 4:11 pm

What do you get if you put a shotgun in a t-remover?

Lisa H.

January 16, 2018 at 7:38 pm

*snerk* Not that there’s a shotgun in Leather Goddesses (right?), but funny.

Ben

October 26, 2023 at 9:57 pm

Mereztky -> Meretzky

Jimmy Maher

November 2, 2023 at 1:05 pm

Thanks!

Joe L

June 19, 2024 at 12:19 am

Hello from the future! The FX version of Shōgun this year is excellent and well worth a watch.

Ranakabuto

November 5, 2024 at 11:33 am

“He never actually became a director, but he did gradually establish himself by dint of pluck and sheer stubbornness as a screenwriter.”

Clavell directed a number of films, including “To Sir, with Love” and “The Last Valley”.

Jimmy Maher

November 5, 2024 at 12:15 pm

Thanks!