In September of 1982 Infocom released their fourth and fifth games, and their second and third of that year, simultaneously. Starcross, by Dave Lebling, was an outer-space adventure in the mold of Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama. We’ll get to that shortly. But today I want to talk about Zork III: The Dungeon Master, the next installment in Infocom’s flagship series.

Although its endgame and one rather elaborate puzzle are borrowed from the PDP-10 Zork, the rest of Zork III is an original work of the indefatigable Marc Blank, a fellow whom I’m coming more and more to recognize as perhaps the key influence behind the Infocom Way. This is after all the guy who co-authored the original PDP-10 Zork, who worked tirelessly to make the parser better, who designed the Z-Machine, who expanded the very definition of an adventure game via Deadline. Zork III isn’t so obviously groundbreaking as Deadline, but it’s a better, more mature piece of work — better than anything that had come before, not only from Infocom, but from anyone. That’s not to say that it’s an easy game. No, it’s hard as nails. Yet it’s difficult for all the right reasons. Here you’ll find no mazes or useless geography, no riddles, no parser games, no hunger or light-source timers or inventory limits (that matter, anyway). No bullshit. You’ll just find a small assortment of puzzles that are more intricate and satisfying than anything we’ve seen before, couched in the most evocative of atmospheres.

As I’ve mentioned before, Zork has always had a schizophrenic personality. The series has never quite decided whether it wants to be goofy, mildly satirical comedies full of the over-the-top excesses of the Flathead clan or mournful tragedies played out amidst the faded grandeur of the erstwhile Great Underground Empire. The PDP-10 game and the first PC game vacillated wildly between both extremes, while Zork II, largely the work of Dave Lebling, played up the light comedy. Zork III is not without some well-placed Flathead jokes, but its main atmosphere is one of windy austerity, with a distinct twinge of sadness for better times gone by. It begins thus:

As in a dream, you see yourself tumbling down a great, dark staircase. All about you are shadowy images of struggles against fierce opponents and diabolical traps. These give way to another round of images: of imposing stone figures, a cool, clear lake, and, now, of an old, yet oddly youthful man. He turns toward you slowly, his long, silver hair dancing about him in a fresh breeze. "You have reached the final test, my friend! You are proved clever and powerful, but this is not yet enough! Seek me when you feel yourself worthy!" The dream dissolves around you as his last words echo through the void....

“Your old friend, the brass lantern, lies at your feet,” we are soon told, a sentence that well-nigh drips with Zork III‘s new-found world-weariness. And indeed, we’re a long way from the famous white house. If Zork I, with its points-for-treasures plot, is almost the prototypical adventure game, Zork III, just as much as the Prisoner games, is all about subverting our expectations of what makes an adventure game. Its most remarkable, peculiar achievement is to simultaneously be a damn good play within the confines of the genre it happily subverts.

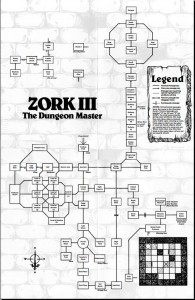

But, onward. Here’s a map of the geography, in case you’d like to follow along as I explore, or (better yet) play along. I’m going to make a real effort not to spoil Zork III as thoroughly as I traditionally have in these analyses; it’s eminently worth struggling with a bit for yourself. My nudges, plus the map and the list of objects to be discovered in each room thereon, will hopefully blunt some of the edges of difficulty while leaving the heart of the experience intact.

From the Endless Stair where we began, we move south into the Junction. Another old friend, our sword, is embedded in a stone here, but there’s no way to pull it out. This “puzzle” is not really a puzzle at all; the sword will come to us, unbidden, when the time comes.

So, we move westward. We climb down a cliff to discover just the thing for an adventurer like us: a treasure chest — albeit a locked one. As we’re fiddling with it:

At the edge of the cliff above you, a man appears. He looks down at you and speaks. "Hello, down there! You seem to have a problem. Maybe I can help you." He chuckles in an unsettling sort of way. "Perhaps if you tied that chest to the end of the rope I might be able to drag it up for you. Then, I'll be more than happy to help you up!" He laughs again.

Every instinct tells us not to trust this guy; Zork I and Zork II have taught us that pretty much everyone in the Great Underground Empire is against us. Surely this fellow just wants to make off with our loot. And what else is an adventure game about if not collecting loot? Sure enough, if we take a chance and do as he asks we learn our suspicions were correct.

The man starts to heave on the rope and within a few moments you arrive at the top of the cliff. The man removes the last few valuables from the chest and prepares to leave. "You've been a good sport! Here, take this, for whatever good it is! I can't see that I'll be needing one!" He hands you a plain wooden staff from the bottom of the chest and begins examining his valuables.

Yet — and here’s where the subversion comes in — the treasure doesn’t matter. The old staff is what we need.

By this point we’ve already noticed something else very strange about Zork III: its scoring system seems completely out of whack. There are just 7 points to be scored, not the hundreds which we’ve come to expect from the earlier games. Further, points are awarded for such innocuous actions as just wandering into a certain completely accessible room, while major breakthroughs go unremarked. It’s possible to have 6 or 7 points and still be completely at sea, nowhere close to actually, you know, solving the game. Once again it seems that Zork III is playing by new rules that we don’t quite understand.

Yet Zork III is a finely crafted adventure as well as a subversive one, the first from Infocom without any howlingly bad design choices. We see this demonstrated in a rather surprising way on the Flathead Ocean. If we stand around here for a randomly determined number of turns, a ship will show up. Then we have one turn to say “Hello, sailor” to receive a potion of invisibility. “Hello, sailor” was a running joke throughout the first two Zork games; thus its appearance here, where it’s finally good for something. For the real oldtimers, there’s also a bit of even more meta meta-humor here: there’s a trivia quiz in the endgame of the original PDP-10 Zork about Zork itself. One of the possible questions is, “In which room is ‘Hello, Sailor’ useful?” The correct answer, in that game, is “None.”

Meta-humor aside, this business on the Flathead Ocean is on the face of it a staggeringly awful puzzle. First we must magically divine that we need to wait around in an otherwise uninteresting location (shades of Catherine the Great’s hairpin from Time Zone); then we must type the One True Thing from a multitude of choices. None of which, of course, would have stopped On-Line or perhaps even an earlier incarnation of Infocom from shoving it in there and being done with it. It’s exactly the sort of puzzle early adventure implementers loved, being trivial to code yet vastly extending the playing time of the game with its sheer obtuseness. Here, however, it’s not actually necessary. The potion only provides an alternate solution to a puzzle in the endgame. Thus the puzzle stands as an Easter egg only for the hardcore who like to plumb every depth and ferret out every secret. I don’t know of a better example of Infocom’s fast-evolving design sensibility than the decision not to make solving this bad puzzle necessary to winning the game.

But there are other, positive rather than negative examples of said sensibility. West of the lake we find what may just be my favorite puzzle in the game, a puzzle which is everything the arbitrary seaside puzzle is not. A magic portal can transport us momentarily not only to another location within this game, but also to locations from Zork I and Zork II. We need to plan for the next phase of our explorations by leaving a light source at a critical location using the portal. This is, at least by some criteria, unfair, as we have to do some learning by death a little later in the game to figure out that we need to do this. Yet it’s also a complex puzzle that grows organically from the sort of intricate, believably modeled storyworld that no one other than Infocom was crafting at this time. Puzzles like this feel shockingly modern in comparison to those of Infocom’s contemporaries.

Interestingly, the portal can also transport us to a fourth Zork game, a preview/advertisement for a work that was obviously already gestating in Blank’s mind. Zork IV, of course, never appeared (at least under that title). It came to me as something of a surprise to realize that Zork on PCs was never conceived by Infocom as a neat trilogy, a reality that seems at odds with the air of doomed finality that becomes more and more prevalent as we get deeper into Zork III. But at this stage Infocom still considered Zork, their flagship series and ongoing cash cow, very much an indefinitely ongoing series. Some players must have wondered just where it was going; the scene from the planned Zork IV is one of the most violent and disturbing in the Infocom canon.

Sacrificial Altar

This is the interior of a huge temple of primitive construction. A few flickering torches cast a sallow illumination over the altar, which is still drenched with the blood of human sacrifice. Behind the altar is an enormous statue of a demon which seems to reach towards you with dripping fangs and razor-sharp talons. A low noise begins behind you, and you turn to see hundreds of hunched and hairy shapes. A guttural chant issues from their throats. Near you stands a figure draped in a robe of deepest black, brandishing a huge sword. The chant grows louder as the robed figure approaches the altar. The large figure spots you and approaches menacingly. He reaches into his cloak and pulls out a great, glowing dagger. He pulls you onto the altar, and with a murmur of approval from the throng, he slices you neatly across your abdomen.

**** You have died ****

This scene would eventually appear, violence intact, in Blank’s next game, where it would jar with the tone of the rest of the game even more dramatically than it does here. However, that game, which did indeed start life as Zork IV, would be wisely retitled Enchanter, situated as its own entity and the first of a new fantasy trilogy.

Zork III is nowhere near so dynamic a system as Deadline. In the ongoing tradition of many adventure games even today, its world is a largely empty, static one. There is, however, one exception. At a randomly determined point of approximately 100 to 150 turns in, an earthquake causes the High Arch above the Aqueduct to collapse. I mention this now because making our escape through the area south of the lake depends on this arch still being intact, as well as the aforementioned light source having been properly placed. (Relatively static it may be, but Zork III nevertheless requires almost as much planning and learning by death as Deadline.) Lest I be accused of praising too much, let me just also note that the aqueduct area contains one of the few stumbles in this otherwise elegantly written game, when Blank suddenly tells us how to feel rather than letting the scenery speak for itself: “You feel a sense of loss and sadness as you ponder this once-proud structure and the failure of the Empire which created this and other engineering marvels.”

At this point we have only one more area west of the Junction to explore: the Land of Shadow. Just as the sailor on the Flathead Ocean feels like a puzzle Blank thought better of, turning it into an Easter egg and alternate solution instead, the Land of Shadow feels like it started life as a maze. Within it we meet a strange, apparently hostile figure. The sword we last saw stuck in the stone suddenly appears in our hand, and we are treated for the last time in the Infocom canon to the randomized combat system Dave Lebling developed for the PDP-10 Zork back in the day. Subversion is still the order of the day, however, so we can’t really die. Nor do we really want to kill. Playing the situation the right way results in an unnerving scene that recalls, among other possibilities, the climactic moment of the Prisoner television series.

>get hood

You slowly remove the hood from your badly wounded opponent and recoil in horror at the sight of your own face, weary and wounded. A faint smile comes to his lips and then his face starts to change, very slowly, into that of an old, wizened man. The image fades and with it the body of your hooded opponent. His cloak remains on the ground.

What is going on here will become more clear — at least a little bit more clear — later. But we’ll wrap things up for today on that ominous note. Next time we’ll tackle the area east of the Junction, and the endgame.

Lisa

September 14, 2012 at 7:44 pm

Not sure which part of that phrase “that matter, anyway” was meant to qualify. Isn’t it possible for the lamp to run out? I leave it behind after positioning the torch with the viewing table, and the torch of course lasts quite long enough with a walkthrough, but I’ve never purposely tried to wait it out.

Scoring system as described in the Invisiclues:

How does the scoring in this game work?

The scoring is a hint as to what is important.

The points are not “earned” by solving problems or acquiring items. You receive a point when you start on a path where you have a potential for progress in the game. [i.e., when you start down a path of action that can lead to acquiring one of the items you need to become the Dungeon Master]

It is possible to have all seven points without correctly solving any of the problems.

Lisa

September 14, 2012 at 7:46 pm

See also http://www.csd.uwo.ca/Infocom/Invisiclues/zork3/chapter8/ for those interested in what actions score points.

Jimmy Maher

September 15, 2012 at 9:53 am

It was really meant to qualify light-source timers and inventory limits.

Yes, it’s possible for the lamp to run out. I believe the torch, however, is magic and thus inexhaustible. (How else could it still be burning when you discover it in a cavern that has presumably been deserted for decades if not centuries?) At any rate, I carried it around for over 600 turns without it going out or giving any sign (“The torch is growing dimmer,” etc.) that it was likely to. And since you need to get through the area that contains the torch before the earthquake that occurs 100-150 turns in or be locked out of victory, I think it’s unlikely that a dead lamp ever becomes a real issue for most players.

Similarly, there is technically an inventory limit, but you need to be carrying virtually every takeable object in the game to hit it. By that point, it’s pretty obvious that some, like the empty can of grue repellent, are useless and can be tossed away. Both of these restrictions strike me more as the legacy of older games that still existed in the standard library of code than as important parts of THIS design.

As for scoring: that makes sense in retrospect, but it’s highly unlikely that any player not playing straight from the InvisiClues would ever figure that out. From the perspective of a player who has no idea when she’s “started on a path where she has potential for progress in the game,” the scoring just seems, well, capricious or flat-out random. :)

Lisa

September 18, 2012 at 1:24 am

As I said, I’ve never tried to wait out the torch to see if it’s possible for it to burn out. I think I remember reading that the ivory torch in Zork I was inexhaustible, but as it’s a treasure I obviously wind up putting it in the trophy case and so have never really considered it.

I agree that the scoring is very obscure – just including the quote for the interest of those reading this post.

matt w

September 15, 2012 at 1:17 am

I just went through what seems like an old-school sequence with the chest, which is to say it made me want to slam my head into my desk:

> tie chest to rope

The chest is now tied to the rope.

The man above you looks pleased. “Now there’s a good friend! Thank you very much, indeed!” He pulls on the rope and the chest is lifted to the top of the cliff and out of sight. With a short laugh, he disappears. “I’ll be back in a short while!” are his last words.

[z/z/z]

A familiar voice calls down to you. “Are you still there?” he bellows with a coarse laugh. “Well, then, grab onto the rope and we’ll see what we can do.” The rope drops to within your reach.

> climb rope

Cliff Base

[which is down from the Cliff Ledge — but i wanted to climb it up!]

[wend my way back to the Cliff]

> climb rope

Cliff Ledge

…A long piece of rope is dangling down from the top of the cliff and is within your reach.

> pull rope

The man scowls. “I may help you up, but not before I have that chest.” He points to the chest near you on the ledge.

> tie chest to rope

You can’t see any chest here.

Now, I screwed up, because I ignored the relatively clear instructions that you can’t climb the rope yourself, but this still betrays a certain lack of state-tracking.

Jimmy Maher

September 15, 2012 at 9:58 am

Yeah, I actually went through a fairly similar sequence on my play. Infocom’s parser was not yet as good as it would be in another year or two –but still much, much better than any of the competition.

matt w

September 15, 2012 at 5:26 pm

Sure, absolutely. Even here, the parser isn’t really at fault — most contemporary IF games probably won’t understand things like “climb rope up” and “climb rope down,” and understanding “grab rope” goes beyond the call of duty — what would really help is “undo.” But it was surprising that they had text keyed to the man and chest when the man and chest weren’t there. Also, I wasn’t sure how to envisage the rope — if it extends down past me to the Cliff Base, why can’t I see it?

Overall, even without the mazes and the light timers, the game is a shock to my new-school sensibilities. I spent a hundred turns without encountering anything I can recognize as a puzzle, let alone solving one (the sword and Royal Puzzle seem like red herrings). Now that I know that the goal is to get the hooded figure’s cloak, that’s a bit of a puzzle, but I’m not sure how I’d have been able to do it. Also, he killed me, and when I was resurrected it seemed as though my staff had disappeared, surely a fate worse than death.

Jimmy Maher

September 16, 2012 at 8:12 am

I came to Zork III from the opposite perspective, having played tons of old, old, old-school adventures for this blog over the past year or so. It therefore struck me as really modern in feel in its complete lack of interest in so many of the old-school tropes. Many of the puzzles in Zork III would fit comfortably into, say, Curses. But then, to a modern player even that game would seem hopelessly old-school.

The sword is a red herring to the extent that pulling it out of the stone is not really a puzzle to be solved. The Royal Puzzle, which I’ll get to in the next post, is however most definitely not. :)

matt w

September 17, 2012 at 7:42 pm

I just realized that I horribly mangled a sentence in my post — what I meant was, “if [the rope] extends down past me to the Cliff Base, why can I tie something to its end?”

Lisa

September 18, 2012 at 1:28 am

Because you can grab it at the middle, where you presumably must be if the end is at Cliff Base, haul up the end and tie the chest to it?

Don’t know – I agree this sequence is a little strange because of how the game interprets commands that have suddenly become ambiguous because of multiple ways of climbing that were not available before. Just saying – it’s certainly physically possible in the scenario you’re envisioning.

matt w

September 18, 2012 at 2:03 am

It’s possible, but it’s still kind of confusing.

Actually, the more I look at the descriptions, the more I think that there’s nothing in them that indicates that the rope reaches all the way to the cliff base. Its description in the Cliff is “A rope is tied to one of the large trees here and is dangling over the side of the cliff, reaching down to the shelf below,” which sure makes it sound as though it ends at the ledge. What I think happened is that they really expect you to type “down” to get from the ledge to the base, but they programmed something like “Instead of climbing the rope: Try going down.” (Except, you know, not in Inform 7.)

Duncan Stevens

September 16, 2012 at 2:16 am

For whatever reason, when I first played this, I never fiddled long enough with the chest for the man to come along–only discovered that via the hints.

Something you’re hinting at and may be getting to: Zork III is certainly Infocom’s first attempt, and possibly anyone’s first attempt, to develop the PC into something more than the player’s avatar. I.e., the PC–theoretically the same PC who has already gathered two games’ worth of treasure–learns, over the course of this game, that treasure isn’t everything and that mercy has a place. (The prologue, with the old man saying “Seek me when you feel yourself worthy!”, hints at this–feel? what is this “feel” you speak of? there has been no “feeling” up to this point–though the subjective side of the story doesn’t get much attention.) Maybe not so exciting now, but noteworthy in 1983.

Jimmy Maher

September 16, 2012 at 8:17 am

The whole trilogy could be read as a chronicle of the evolution of adventure games. In the first game, we collect treasures just for the hell of it (or to score points and “win”). In the second, we collect treasures, but ultimately for a purpose (to give to the demon to access the next game). In the third, we’re not interested in treasures at all.

DaveK

April 10, 2015 at 6:46 pm

The trilogy was not a “chronicle” of the evolution of adventure games; it *was* the evolution of adventure games! It is the (not-) missing link between Colossal Cave and modern IF; the progress that it made is the foundation on which modern IF rests.

Vince

November 2, 2023 at 5:19 pm

“In the first game, we collect treasures just for the hell of it (or to score points and “win”). In the second, we collect treasures, but ultimately for a purpose (to give to the demon to access the next game). In the third, we’re not interested in treasures at all.”

I’m not sure there is a huge difference between 2 and 3 in this regard. You really are collecting some McGuffins you need to access the endgame, even if the process is more obfuscated in 3 and the items are usually at the end of more elaborate puzzles.

Steve

April 1, 2017 at 12:14 am

The “aqueduct destruction” puzzle was outright terrible game design. It hinges on you somehow surmising that the destruction of this particular old, decaying structure — in a world that is positively FULL of old, decaying structures — only happened in the period since you started the game.

Even if you visited the balcony before the earthquake, the game gives you NO indication that anything the aqueduct has in any way changed before & after the quake: the room description is exactly the same. So when we get to the aqueduct itself later, why would we assume the collapsed arch is a recent development? Even its water channel exit is blocked by “rubble” from the very beginning of the game, another indication that this thing has been decrepit for some time.

So did this remain un-hinted as to arbitrarily up the game’s difficulty level? Or did they just never consider it an issue? Adding a “recently-damaged” to the aqueduct description sure would have been useful in indicating that the only solution to the puzzle was to RESTART THE GAME FROM SCRATCH. Or maybe adding a lingering cloud of dust to the area (centering around the fallen arch after its collapse) if they wanted to be more subtle. Or in the opposite direction, how about an aftershock that collapses another arch while the player is in the aqueduct itself? I mean, practically ANYTHING would have been better than the way it was done.

(Also, the earthquake mechanic itself was clearly implemented as a means to limit museum access for the time travel puzzle; so its mere existence would not necessarily lead one to go looking for places it might have had an effect…)

You do seem to have a soft spot for the game, which might be why you were so willing to give this “puzzle” a pass (also, you must have known the timber was a red herring; else you would have discovered that saying the game has virtually “no inventory limit” was patently wrong!). There was also an amazing laziness in so many of the descriptions: “I see nothing interesting about the [noun].” (This might carry over from the earlier games, but is that even an excuse? You can find nothing interesting to say about a jeweled sceptre, a Crown Jewel of the Underground Empire? Really??)

The game was definitely better-implemented than the ones that came before it, but I was only inspired to comment on this one because your glowing praise (without the usual “for its time” caveats) suggested a much richer game experience than what one actually gets after playing their later games… :)

Matt Giuca

June 1, 2019 at 9:04 pm

FYI, you’re not stuck if there earthquake has already happened at this point, as long as you don’t drop down to the aqueduct. From the Key Room, Save, then head back west the way you came through the dark cave. There is a small but not insignificant chance of surviving the grues until you get back to the lake. Then you can swim back north, diving down to retrieve the items you were carrying.

Though, I agree it would have been better telegraphed so you actually realise that the aqueduct collapsed during your game, not a long time ago. I certainly assumed it was a static part of the scenery and not a dynamic event.

Sascha Wildner

March 5, 2018 at 9:11 pm

“The sword we lost saw stuck in the stone” -> “The sword we last saw stuck in the stone”?

Jimmy Maher

March 6, 2018 at 9:26 am

Thanks!

Ben

July 25, 2020 at 6:48 pm

negative example of -> negative examples of

Jimmy Maher

July 26, 2020 at 8:37 am

Thanks!

Will Moczarski

August 14, 2020 at 12:17 am

“ one of the few stumbles in this otherwise elegantly written game, when Blank suddenly tells us how to feel rather than letting the scenery speak for itself”

That always struck me as a rather bold and successful twist on Blank’s behalf but I guess that preferences may differ. The aforementioned “Enchanter” room always felt like the actual “stumble” to me, as its pulp fantasy vibe clashes with virtually everything that’s so beautiful about “Zork III.”

Also, the scene that makes you think of “The Prisoner” always seemed like a thinky veiled reference to “The Empire Strikes Back” to me. While I prefer “The Prisoner”, of course, the comparison feels like a bit of a stretch to me but of course that’s highly subjective, too.

Your posts about “Zork III” are among my favourite texts of yours – they are beautifully written analyses of a game with beauty aplenty.

Anders

June 10, 2022 at 4:37 pm

“At this point we have only more area west of the Junction to explore: the Land of Shadow.”

= At this point we have only one more area?

Jimmy Maher

June 14, 2022 at 3:27 pm

Thanks!

Vince

November 2, 2023 at 5:12 pm

I agree that this is the best Zork so far, the puzzles really elevate it over its predecessors.

The “No bullshit” statement is a bit excessive, though, there are still random deaths, timed/random events and about a million ways to get dead-ended. The score system is particularly puzzling and, as a consequence, correctly gauging progress is impossible.

Still, playing it blindly I only needed one hint to finish it (and it’s totally on me), so I would consider it “fair” by early IF standards.

arcanetrivia

November 3, 2023 at 12:11 am

I’m curious what was the one hint you needed.