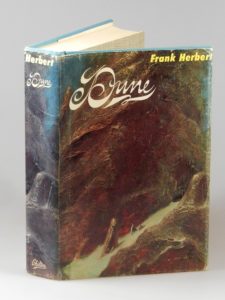

In 1965, two works changed the face of genre publishing forever. Ace Books that year came out with an unauthorized paperback edition of an obscure decade-old fantasy trilogy called The Lord of the Rings, written by a pipe-smoking old Oxford don named J.R.R. Tolkien, and promptly sold hundreds of thousands of copies of it. And the very same year, Chilton Books, a house better known for its line of auto-repair manuals than for its fiction, became the publisher of last resort for Frank Herbert’s epic science-fiction novel Dune. While Dune‘s raw sales weren’t initially quite so impressive as those of The Lord of the Rings, it was recognized immediately by science-fiction connoisseurs as the major work it was, winning its year’s Nebula and Hugo Awards for Best Novel (the latter award alongside Roger Zelazny’s This Immortal).

It may be that you can’t judge a book by its cover, but you can to a large extent judge the importance of The Lord of the Rings and Dune by their thickness. Genre novels had traditionally been slim things, coming in at well under 300 pocket-sized mass-market-paperback pages. These two novels, by contrast, were big, sprawling works. The writing on their pages as well was heavier than the typical pulpy tale of adventure. Tolkien’s and Herbert’s novels felt utterly disconnected from trends or commercial considerations, redolent of myth and legend — sometimes, as plenty of critics haven’t hesitated to point out over the years, rather ponderously so. At a stroke, they changed readers’ and publishers’ perception of what a fantasy or science-fiction novel could be, and the world of genre publishing has never looked back.

In the years since 1965, almost as much has been written of Dune as The Lord of the Rings. Still, it’s new to us. And so, given that it suddenly became a very important name in computer games circa 1992, we should take the time now to look at what it is and where it came from.

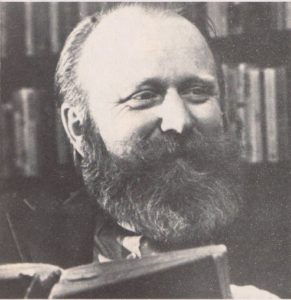

At the time of Dune‘s publication, Frank Herbert was a 45-year-old newspaperman who had been dabbling in science fiction — his previous output had included one short novel and a couple of dozen short stories — since the early 1950s. He had first been inspired to write Dune by, appropriately enough, sand dunes. Eight years before the novel’s eventual publication, the San Francisco Examiner, the newspaper for which he wrote, sent him to Florence, Oregon, to write about government efforts to control the troublesomely shifting sand dunes just outside of town. It didn’t sound like the most exciting topic in the world, and, indeed, he never managed to turn it into an acceptable article. Yet he found the dunes themselves weirdly fascinating:

I had far too much for an article and far too much for a short story. So I didn’t know really what I had—but I had an enormous amount of data and avenues shooting off at all angles to get more… I finally saw that I had something enormously interesting going for me about the ecology of deserts, and it was, for a science-fiction writer anyway, an easy step from that to think: what if I had an entire planet that was desert?

The other great spark that led to Dune wasn’t a physical environment, nor for that matter a physical anything. It was a fascination with the messiah complex that has been with us through all of human history, even though it has seldom, Herbert believed, led us to much good. Somehow this theme just seemed to fit with a desert landscape; think of the Biblical Moses and the Exodus.

I had this theory that superheroes were disastrous for humans, that even if you postulated an infallible hero, the things this hero set in motion fell eventually into the hands of fallible mortals. What better way to destroy a civilization, society, or race than to set people into the wild oscillations which follow their turning over their judgment and decision-making faculties to a superhero?

Herbert worked on the novel off and on for years. Much of his time was spent in pure world-building — or, perhaps better said in this case, galaxy-building — creating a whole far-future history of humanity among the stars that would inform and enrich any specific stories he chose to set there; in this sense once again, his work is comparable to that of J.R.R. Tolkien, that most legendary of all builders of fantastic worlds. But his actual story mostly took place on the desert planet Arrakis, also known as Dune, the source of an invaluable “spice” known as melange, which confers upon humans improved health, longer life, and even paranormal prescience, while also allowing some of them to “fold space,” thus becoming the key to interstellar travel. As the novel’s most popular and apt marketing tagline would put it, “He who controls the spice controls the universe!” The spice has made this inhospitable world, where water is so scarce that people kill one another over the merest trickle of the stuff, whose deserts are roamed by gigantic carnivorous sandworms, the most valuable piece of real estate in the galaxy.

The novel centers on a war between two great trading houses, House Atreides and House Harkonnen, for control of the planet. The politics involved, not to mention the many military and espionage stratagems they employ against one another, are far too complex to describe here, but suffice to say that Herbert’s messiah figure emerges in the form of the young Paul Atreides, who wins over the nomadic Fremen who have long lived on Arrakis and leads them to victory against the ruthless Harkonnen.

Dune draws heavily from any number of terrestrial sources — from the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, from the more mystical end of Zen Buddhism, from the history of the Ottoman Empire and the myths and cultures of the Arab world. Nevertheless, the whole novel has an almost aggressively off-putting otherness about it. Herbert writes like a native of his novel’s time and place would, throwing strange jargon around with abandon and doing little to clarify the big-picture politics of the galaxy. And he shows no interest whatsoever in explaining that foremost obsession of so many other science-fiction writers, the technology and hardware that underpin his story. Like helicopters and diving suits to a writer of novels set in our own time and place, “ornithopters” and “stillsuits,” not to mention interstellar space travel, simply are to Dune‘s narrator. Meanwhile some of the bedrock philosophical concepts that presumably — hopefully! — unite most of Dune‘s readership — such ideas as fundamental human rights and democracy — don’t seem to exist at all in Herbert’s universe.

This wind of Otherness blowing through its pages makes Dune a famously difficult book to get started with. Those first 50 or 60 pages seem determined to slough off as many readers as possible. Unless you’re much smarter than I am, you’ll need to read Dune at least twice to come to anything like a full understanding of it. All of this has made it an extremely polarizing novel. Some readers love it with a passion; some, like yours truly here, find it easier to admire than to love; some, probably the majority, wind up shrugging their shoulders and walking away.

In light of this, and in light of the way that it broke every contemporary convention of genre fiction, beginning but by no means ending with its length, it’s not surprising that Frank Herbert found Dune to be a hard sell to publishers. The tropes were familiar enough in the abstract — a galaxy-spanning empire, interstellar war, a plucky young hero — but the novel, what with its lofty, affectedly formal prose, just didn’t read like science fiction was supposed to. Whilst allowing what amounted to a rough draft of the novel to appear in the magazine Analog Science Fiction in intermittent installments between December 1963 and May 1965, Herbert struggled to find an outlet for it in book form. The manuscript was finally accepted by Chilton only after being rejected by over twenty other publishers.

Those other publishers would all come to regret their decision. Dune took some time to gain traction with readers outside science fiction’s intelligentsia; Herbert didn’t make enough money from his fiction to quit his day job until 1969. But the oil embargoes of the 1970s gave this novel that was marked by such Otherness an odd sort of social immediacy, winning it many readers outside the still fairly insular community of written science fiction, making it a trendy book to have read or at least to say you had read. For many, it now read almost like a parable; it wasn’t hard to draw parallels between Arrakis’s spice and our own planet’s oil, nor between the Fremen of Arrakis and the cultures native to our own planet’s great oil-rich deserts. As critic Gwyneth Jones puts it, Dune is, among other things, a depiction of “scarcity, and the kind of human culture that scarcity produces.” It was embraced by many in the environmentalist movement, who read it it as a cautionary tale perfect for an era in which we earthbound humans were being forced to confront the reality that our planet’s resources are not infinite.

So, Dune eventually sold a staggering 12 million copies, becoming by most accounts the best-selling work of genre science fiction in history. And so we arrive at one final parallel to The Lord of the Rings: that of a book that was anything but an easy read in the conventional sense nevertheless selling in quantities to rival any beach-and-airport time-waster ever written. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose was famously described at the height of its 1980s popularity as a book that everyone owned and almost no one had ever managed to get all the way through. Dune may very well be the closest equivalent in genre fiction.

Herbert wrote five sequels to Dune, none of which are as commonly read or as highly regarded among critics as the first novel. [1]As for the flood of more recent Dune novels, written by Frank Herbert’s son Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson, previously a prolific author of X-Files and Star Wars novels and other low-hanging fruit of the literary landscape: stay far, far away. One might say, however, that the second and third novels at least — Dune Messiah (1969) and Children of Dune (1976) — are actually necessary to appreciate Herbert’s original conception of the work in its entirety. He had always conceived of Dune as an epic tragedy in the Shakespearean sense, but reading the first book alone can obscure this fact. That book is, as the science-fiction scholar Damien Broderick puts it, typical pulp science fiction in at least one sense: it satisfies “an adolescent craving for an imaginary world in which heroes triumph by a preternatural blend of bravery, genius, and sci.” It’s only in the second and third books that Paul Atreides, the messiah figure, begins to fail, thus illustrating how a messiah can, as Herbert says, “destroy a civilization, society, or race.” That said, it would be the first novel alone with which almost all media adaptations would concern themselves, so it will also monopolize our attention in these articles.

Dune‘s success was such that it inevitably attracted the interest of the film industry. In 1972, the British producer Arthur P. Jacobs, the man behind the hugely successful Planet of the Apes films, acquired the rights to the series, but he had the misfortune to die the following year, before his plans had gotten beyond the storyboarding phase.

Yet Dune‘s trendiness only continued to grow, and interest in turning it into a film remained high among people who wouldn’t have been caught dead with any other science-fiction novel. In 1974, the rights passed from Jacob’s estate to Alejandro Jodorowsky, a transgressive Chilean director who claimed to once have raped one of his actresses in the name of his Art. Manifesting an alarming obsession with the act, he now planned to do the same to Frank Herbert:

It was my Dune. When you make a picture, you must not respect the novel. It’s like you get married, no? You go with the wife, white, the woman is white. You take the woman, if you respect the woman, you will never have child. You need to open the costume and to… to rape the bride. And then you will have your picture. I was raping Frank Herbert, raping, like this! But with love, with love.

The would-be rape victim could only look on in disbelief: “He had so many personal, emotional axes to grind. I used to kid him, ‘Well, I know what your problem is, Alejandro. There is no way to horsewhip the pope in this story.'”

Jodorowsky planned to fill the cast and crew of the film, which would bear an estimated price tag of no less than $15 million, with flotsam washed up from the more dissipated end of the celebrity pool: Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, Charlotte Rampling, Salvador Dali, Mick Jagger, Alain Delon. But, even in this heyday of Porno Chic, no one was willing to entrust such an erratic personality with such a budget, and the project fizzled out after Jodorwsky had blown through $2 million on scripts, concept art, and the drugs that were needed to fuel it all.

In the meantime, the possibilities for cinematic science fiction were being remade by a little film called Star Wars. Indeed, said film bears the clear stamp of Dune, especially in its first act, which takes place on a desert planet where water is the most precious commodity of all. And certainly the general dirty, lived-in look of Star Wars, so distinct from the antiseptic futures of most science fiction, owes much to Dune.

In the wake of Star Wars, Dino De Laurentiis, one of the great impresarios of post-war Italian cinema, acquired the rights to Dune from Jodorowsky’s would-be backers. He secured a tentative agreement with Ridley Scott, who was just finishing his breakthrough film Alien, to direct the picture. Rudy Wurlitzer, screenwriter of the classic western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, wrote three drafts of a script, but the financing necessary to begin production proved hard to secure. Thus in 1981 the cinematic rights to Dune, which Herbert had sold away for a span of nine years to Arthur P. Jacobs back in 1972, finally reverted to the author after their extended but fruitless world tour.

Yet De Laurentiis remained passionate about his Dune film — so much so that he immediately entered into negotiation with Herbert to reacquire the rights. Having watched various filmmakers come close to doing unspeakable things to his creation over the previous decade — even Wurlitzer’s recent script reportedly added an incest plot line involving Paul Atreides and his mother — Herbert insisted that he must at least be given the role of “advisor” to any future film. De Laurentiis agreed to this.

He was so eager to make a deal because Dune had suddenly looked to be back on, for real this time, just as the rights were expiring. His daughter, Raffaella De Laurentiis, had taken on the Dune film as something of a passion project of her own. She was riding high with a brand of blockbuster-oriented, action-heavy fare that was quite different from the films of her father’s generation. She was already in the midst of producing Conan the Barbarian, starring a buff if nearly inarticulate former bodybuilding champion named Arnold Schwarzenegger; it would become a major hit, launching Schwarzenegger’s career as Hollywood’s go-to action hero over the next couple of decades. But the Dune project would be a different sort of beast, a sort of synthesis of father and daughter’s priorities: a big-budget film with an art-film sensibility. For Ridley Scott had by this time moved on to other projects, and Dino and Raffaella De Laurentiis had a surprising new candidate in mind to direct their Dune.

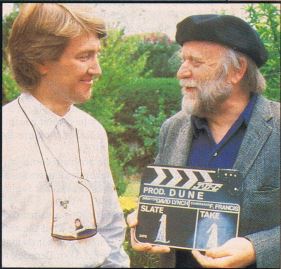

David Lynch and Frank Herbert. Interviewers were constantly surprised at how normal Lynch looked and acted in person, in contrast to his bizarre films. Starlog magazine, for example, wrote of his “sculptured hair [and] jutting boyish features,” saying he was “extremely polite and well-mannered, the antithesis of enigma. Not a hint of phobic neurosis or deep-seated sexual maladjustment.”

David Lynch was already a beloved director of the art-film circuit, although his output to date had consisted of just two low-budget black-and-white movies: Eraserhead (1977), a surrealistic riot of a horror film, and The Elephant Man (1980), a mournful tragedy of prejudice and isolation. He would seem to stand about as far removed from the family-friendly fare of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg’s new Hollywood as it was possible to get. And yet that mainstream of filmmakers saw something — something having to do with his talent for striking, kinetic visuals — in the 36-year-old director. In fact, Lucas actually asked him whether he would be interested in directing the third Star Wars film, Return of the Jedi, whereupon Lynch rather peremptorily turned the offer down, saying he wasn’t interested in making sequels to other people’s films. But when Dino De Laurentiis approached him about Dune he was more receptive. Lynch:

Dino’s office called me and asked if I had ever read Dune. I thought they said “June.” I never read either one of ’em! But once I got the book, it’s like when you hear a new word. And I started hearing it more often. Then, I began finding out that friends of mine had already read it and freaked out over it. It took me a long time to read. Actually, my wife forced me to read it. I wasn’t that keen on it at first, especially the first 60 pages. But the more I read, the more I liked. Because Dune has so many things that I like, I said, “This is a book that can be made into a film.”

Lynch joined screenwriters Eric Bergen and Christopher De Vore for a week at Frank Herbert’s country farmhouse, where they hammered out a script which ran to a hopelessly overlong 200 pages. As the locale would indicate, Herbert was involved in the creative process, but kept a certain distance from the details: “This is a translation job. I wouldn’t presume to be the person who should translate Dune from English to French; my French is execrable. It’s the same with a movie; you go to the person who speaks ‘movie.'”

The script was rewritten again and again in the months that followed, the later drafts by Lynch alone. (He would be given sole credit as the screenwriter of the finished film.) In the process, it slimmed down to a still-ambitious 135 pages. And with that, and with the De Laurentiis father and daughter having lined up a positively astronomical amount of financing from Universal Pictures, who were desperate for a big science-fiction franchise of their own to rival 20th Century Fox’s Star Wars and Paramount’s Star Trek, a real Dune film finally got well and truly underway.

Raffaella De Laurentiis and Frank Herbert with the actors Kyle MacLachlan and Francesca Annis on the set of Dune, 1983.

Rehearsals and pre-production began in the Sonora Desert outside of Mexico City in October of 1982; actual shooting started the following March, and dragged on over many more months. In the lead role of Paul Atreides, Lynch had cast a 25-year-old Shakespearean-trained stage actor named Kyle MacLachlan, who had never acted before a camera in his life. Nor, at six feet tall and 155 pounds, was he built much like an action hero. But he was trained in martial arts, and he gave it his all over a long and difficult shoot.

Joining him were a number of recognizable character actors, such as the intimidating Swede Max von Sydow, cast in the role of the Fremen leader Kynes, and the villain specialist Kenneth McMillan, all but buried under 200 pounds of fake silicone flesh as the disgustingly evil — or evilly disgusting — Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. Patrick Stewart, later to become famous in the role of Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s Captain Jean-Luc Picard, played Paul’s martial mentor Gurney Halleck. In a bit of stunt casting, Sting of the rock band the Police, deemed “biggest band in the world” by any number of contemporary critics, took the role of one of the supporting cast of villains — a role which would, naturally, be blown out of all proportion by the movie’s promoters. To a person, everyone involved with the shoot remembers it as being uncomfortable at best. “I was taxed on almost every level as a human being,” says MacLachlan. “Mexico City is not one of the most pleasant spots in the world to be.” The one thing they all mention is the food poisoning; almost everyone among cast and crew got it at one time or another, and some lived with it for the entirety of the months on end they spent in Mexico.

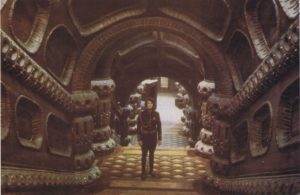

Universal Pictures had given David Lynch, this young director who was used to shooting on a shoestring budget, an effective blank check in the hope that it would yield the next George Lucas and/or the next Star Wars. Lynch didn’t hesitate to spend their money, building some eighty separate sets and shooting hundreds of hours of footage. Even in Mexico, where the peso was cheap, it added up. Universal would later claim an official budget of $40 million, but rumblings inside Hollywood had it that the real total was more like $50 million. Either figure was more than immense enough to secure Dune the title of most expensive Universal film ever. (For comparison’s sake, consider that the contemporary big-budget blockbusters Return of the Jedi and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom cost approximately $40 million and $30 million respectively.)

The shoot had been difficult enough in itself, but the film first began to show the telltale signs of a doomed production only in the editing phase, as Lynch tried to corral his reams of footage into a finished product. He clashed repeatedly with Raffaella De Laurentiis and Universal, both of whom made it clear that they expected a relatively “clean,” PG-rated film with a coherent narrative through line for their money. Such qualities weren’t, of course, what David Lynch was known for. But the director had failed to secure final-cut rights to the film, and he was repeatedly overridden. Finally, he all but removed himself from the process altogether, and Raffaella De Laurentiis herself cobbled together much of the finished film, going so far as to shoot her own last-minute bridging scenes whilst layering clumsy voice-overs and internal monologues over the top, all in a (failed) effort to make the labyrinthine plot comprehensible to a casual audience. Meanwhile Universal continued to spew forth a fountain of hype about “Star Wars for adults” and “the end of the pulp era of science-fiction movies,” whilst continuing to plaster Sting, looking fetching in his black leather, across their “Coming Attractions” posters and trailers as if he was the star. Dune was set for a fall.

And, indeed, the finished product, which arrived in theaters in December of 1984, provided a rare opportunity for every corner of movie fandom and criticism to unite in hatred. The professional critics, most of whom had never read the book, found the film, even with all the additional expository voice-overs, as incomprehensible as Raffaella De Laurentiis had always feared they would. Fans of the novel had the opposite problem, bemoaning the plot simplification and the liberties taken with the story, complaining about the way that all of the thematic texture had been lost in favor of Lynchian weirdness for weirdness’s sake. And the all-important general audience, for their part, stayed away in droves, making Dune one of the more notorious flops in cinematic history. Just like that, Universal Pictures’s dream of a Star Wars franchise of their own went up in smoke.

Seen today, free of the hype and the resultant backlash, the film isn’t as bad as many remember it; many of its scenes are striking in that inimitable Lynchian way. But it doesn’t hang together at all as a holistic experience, and its best parts are often those that have the least to do with its source material. Many over the years have suspected that there’s a good film hidden somewhere in all that footage Lynch shot, if it could only be freed from the strictures of the two-hour running time demanded by Universal; Lynch’s own first rough cut, they point out, was reportedly at least twice that long. Yet various attempts to rejigger the material — including a 1988 version for television that ballooned the running time to more than three hours — haven’t yielded results that feel all that much more holistically satisfying than the original theatrical cut. The film remains what it was from the first, a strange hybrid stranded in a no-man’s land between an art film and a conventional blockbuster, not really working as either. At bottom, the film reflects a hopeless mismatch between its director and its source material. What happens when you ask a brilliant director with very little interest in plot to film a novel famous for its intricate plot? You get a movie like David Lynch’s Dune. Perhaps the kindest thing one can say about it is that it is, unlike so many of Hollywood’s other more misbegotten projects, an interesting failure.

Lynch disowned the film almost immediately. He’s generally refused to talk about it at all in interviews since 1984, beyond dismissing it as a “sell-out” on his part. The one positive aspect of the film which even he will admit to is that it brought Kyle MacLachlan to his attention. The latter starred in Lynch’s next film as well, the low-budget psychological-horror picture Blue Velvet (1986), which rehabilitated its director’s critical reputation at a stroke at the same time that it marked the definitive end of his brief flirtation with mainstream sensibilities. MacLachlan would go on to find his most iconic role as the weirdly impassive FBI agent Dale Cooper in Lynch’s supremely weird television series Twin Peaks.

The Dino de Laurentiis Corporation had invested everything they had and then some in their Dune film. They went bankrupt in the aftermath of its failure — but, in typical corporate fashion, a phoenix known as the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group soon emerged from the ashes. Just to show there were no hard feelings, one of the reincarnated production company’s first films was David Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

Surprisingly in light of the many readers who complained so vociferously about the liberties the Dune film took with his novel, Frank Herbert himself never disowned it, speaking of it quite warmly right up until his death. But sadly, that event came much earlier than anyone had reckoned it would: he died in 1986 at age 65, the victim of a sudden blood clot in his lung that struck just after he had undergone surgery for prostate cancer.

Dune did come to television screens in 2000, in a rather workmanlike miniseries adaptation that was more comprehensible and far more faithful to the novel than Lynch’s film, but which lacked the budget, the acting talent, or the directorial flair to rival its predecessor as an artistic statement. Today, almost half a century after Arthur P. Jacobs first began to inquire about the film rights, the definitive cinematic Dune has yet to be made.

There is, however, one other sort of screen on which Dune has undeniably left a profound mark: not the movie or even the television screen, but the monitor screen. It’s in that direction that we’ll turn our attention next time.

(Sources: the books The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn and Frank Herbert by Timothy O’Reilly; Starlog of January 1983, May 1984, October 1984, November 1984, December 1984, February 1985, and June 1986; Enter of December 1984; the online articles “Jodorowsky’s Dune Didn’t Get Made for a Reason… and We Should All Be Grateful For That” and “David Lynch’s Dune is What You Get When You Build a Science Fictional World With No Interest in Science Fiction” by Emily Asher-Perrin.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | As for the flood of more recent Dune novels, written by Frank Herbert’s son Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson, previously a prolific author of X-Files and Star Wars novels and other low-hanging fruit of the literary landscape: stay far, far away. |

|---|

Lars

November 23, 2018 at 4:31 pm

Prostate, not prostrate.

Sniffnoy

November 23, 2018 at 6:54 pm

Also in typospotting: you have “flare” for “flair” near the end.

Jimmy Maher

November 24, 2018 at 4:50 am

Thanks!

Jimmy Maher

November 24, 2018 at 4:49 am

Thanks!

Mike Rubin

November 23, 2018 at 5:17 pm

Thanks so much for taking this one on! My sharpest memory of the Dune movie, when it came out in theaters, is that it was the first and only film I’ve seen where the theater actually handed out a paper “glossary” with the names and descriptions of the houses, planets, and characters in the movie, since people who hadn’t read the book were hopelessly lost in its complexity.

Brian

November 27, 2018 at 11:57 am

That’s funny, my first thought was “Oh yeah, I remember them handing out an explanation sheet!”

I enjoyed the movie but was already a sci fi nerd. I did read the books shortly thereafter, although I found them progressively unrewarding and ponderous.

Sp1ce b0b

November 23, 2018 at 5:21 pm

Great read and insights about the movie production! Can’t wait for part 2.

LOTR and Dune (an sequels) surely impressed me a tad when I read them as a teenager.

Dan Simmons’ Hyperion is right there as well, and no director dared to adapt it yet.

Ivan Toshkov

November 24, 2018 at 10:18 am

You just named some of my favorite books! Can you suggest something else as well?

For my part, I also like The Name of the Rose, but I love Foucault Pendulum! I think it’s easily the most polarizing book of the bunch. Very few of my friends managed to read it at all, and just one enjoyed it almost as much as me.

Dune was first translated and published in Bulgaria 1987 and 1988. The book was split in two, and fortunately for me, I started reading it when the second one was also published. Besides the fact that I had the whole story, the dictionary was available in each tome, so I could more easily use it.

Oliver

November 26, 2018 at 1:08 pm

Since Jimmy talks here about games, there is great game based on “The name of the Rose” for Spectrum, Amstrad and MSX, “La abadia del crimen” (The abbey of crime), a very famous Spanish title where you roam around an abbey in truly isometric glory. Sadly they didn’t get the rights for the book but the plot is the same

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Abad%C3%ADa_del_Crimen

Pedro Timóteo

November 27, 2018 at 10:03 am

There’s a free(!) remake on Steam, which looks pretty good (just search for “The Abbey of Crime Extensum”), though perhaps a bit more “cartoony” than the original (on the CPC and Spectrum), which I always thought felt pretty oppressive.

Venya058

November 23, 2018 at 7:18 pm

Footnote 1 is on point.

I admit to enjoying Lord of the Rings immensely as a a film series, and only appreciating it as a series of books, which I found pretty tedious. (This is reversed for The Hobbit.)

I found the first three Dune books utterly engrossing. I’d only read the first until university, and then a roommate’s friend lent me the rest of the series, one at a time. Maliciously, it turned out. I adored the first three, slogged through the next two, and felt some real hope that we were heading toward resolution at the end of book 6. I brought it back and asked for the next one. “Oh, there aren’t any more. Dude died.” My alleged friend had been waiting for weeks to spring that on me.

Captain Kal

November 23, 2018 at 7:32 pm

When I first watched in cinemas, I could not make head or tails out of it. I was expecting, and I dragged my friends with me, expecting to watch something like “Star Wars”. I was devastated, not to mention that my friends blamed me, for them wasting their hard earned pocket money. The music was fantastic though.

It became one of my favourites movies many years later. And I think you will find the following clip hilarious:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fb_LO7gJo-4

Benjamin Vigeant

November 23, 2018 at 8:03 pm

Perhaps because of my affinity for Lynch, I can’t bring it to myself to hate or even really dislike his Dune. It’s gorgeous and weird, and I love Kyle MacLaughlin in it.

I think he was able to do Blue Velvet entirely because of Dune – it was his reward for doing the studio “blockbuster”. He also has maintained final cut on everything since, which is why he walked off the third season of Twin Peaks for a short bit.

Keith Palmer

November 24, 2018 at 2:33 am

I’m just at the age where my first awareness of Dune came from a “storybook adaptation” of the movie (which, along with comic book adaptations and novelizations, was how I first experienced most of the totemic films of the 1980s…) A few years later, as I was going into high school, I started reading Herbert’s actual novels, if to wind up with that unfortunate sense of “diminishing returns” you alluded to (and feeling more or less lost as to what was happening in the last book or so). I have, though, read the first novel several times, the last time fairly recently. However, I still have to admit to my own uneasiness at the missing “bedrock philosophical concepts” you mentioned, although they can seem unfortunately scarce to me in a great deal of “interstellar science fiction…”

anonymous

November 24, 2018 at 4:01 am

Where you have “in the name his Art,” you’ve left out an “of.”

For my part, I loved the movie, but it’s weird as hell and I would never recommend it to anyone.

Jimmy Maher

November 24, 2018 at 4:56 am

Thanks!

Christian Studer

November 24, 2018 at 7:10 am

Ah, thanks for the article!

But now I have to go and read the book again… :-/

Christian Studer

November 24, 2018 at 2:28 pm

Oh no, I jus realized that I don’t own a physical copy of Dune.

Anybody can recommend a fancy edition? (Not the Folio Society one, that’s too fancy…)

Laertes

November 24, 2018 at 12:59 pm

It is Raffaella, not Raffealla. Great article as usual. I love Dune, I have read it several times both in spanish when my english was very limited and in english. And I played countless hours Dune II.

Jimmy Maher

November 25, 2018 at 2:44 am

Thanks!

Greg Carter

November 24, 2018 at 6:39 pm

Thanks for a fascinating article! Like many diehard Dune fans (I just finished the Audible audiobook version, and have read it on paper many times over the years), I was disappointed in the Lynch film. It was interesting to read about how it came to be the mess that it was.

As you say, “…the definitive cinematic Dune has yet to be made.”

That may be about to change! I’m pretty excited about Denis Villeneuve’s version, which is expected to get started early next year.

https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2018/07/denis-villeneuve-is-remaking-dune-and-thats-a-good-thing/

David Cornelson

November 24, 2018 at 8:05 pm

Dune was/is one of my top five favorite books of all time. I loved it the second I picked it up, embraced its complexity, politics, religion, and nuance.

Few people were more excited to sit for the Lynch movie.

I walked out steaming mad. The result was a simplistic caracture of the novel with a huge plot point replaced with a throat weapon.

There’s a new Dune in the works. One can only hope he gets it right.

I second the comment on the non-Frank Dune sequels. They are horrible and shouldn’t even be used to hold a door open.

Martin

November 24, 2018 at 11:21 pm

I’ve read all six of the originals long ago but not any of the Brian Herbert/Kevin Anderson efforts. There seems to be quite a number of them, so something must be going right with them. So what’s the consensus on what’s wrong with them? Is it the writing, the plotting or what exactly?

Alex Smith

November 25, 2018 at 12:20 am

Yes.

Eric

November 25, 2018 at 5:04 am

I’m not sure how best to describe what exactly is wrong with the Brian Herbert books – others here can probably answer that better than I can. But I can attest all the same that every single one of the non-Frank books I’ve tried to read (and I tried reading at least 5 of them) has been utterly excruciating to get through. I wanted badly to find something to like about these books because I am so fascinated and intrigued by the Dune universe, but it’s like Herbert and Anderson were given this amazing universe to work with on a silver platter and they took that platter and ran over it with a steamroller, stabbed it with a pick axe and then chucked what was left into an incinerator. Yes, they really are that bad.

whomever

November 25, 2018 at 4:10 pm

Great Article Jimmy! Really interesting, I hadn’t known any of the complicated backstory of the film, and count me as one of the people who actually like it, though I totally get it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. (I think it’s at least hit “cult classic” at this point). Patrick Stewart was already at least somewhat known as a Shakespearian actor and of course had played Sejanus in “I, Claudius” (which probably has the best single British cast in any TV before or afterwards).

Your article already goes into this, but Dune has really aged well in the context of today, with Spice being a metaphor for oil, ecology, a whole pile of other themes that or sort of recent (there’s even some hints the Fremen are descendants of Bedouin given their mention of the Hajj). A Lot of Sci-Fi from that era can’t say the same. And as I’m sure you are going to get to, it’s influence on gaming is epic.

whomever

November 25, 2018 at 4:10 pm

Of interest to this Blog, Frank Herbert also apparently wrote some books on home computers, such as https://www.amazon.com/Without-Youre-Nothing-Essential-Computers/dp/0671412876. This is especially ironic as a major part of the Dune backstory is the Butlarian Jihad, which basically banned computers. I’ve never run into a copy (could order on Amazon I supposed). I’ve also been curious about the picture. I suspect that’s an artists’s interpretation of a computer as it’s no model I recognize, but I’d be curious if it was a real machine.

[Apologies if this is published twice, I seem to be having issues]

Jimmy Maher

November 25, 2018 at 4:40 pm

I only know of one Frank Herbert book on computers, the one you link to. I’d actually written several paragraphs about this topic, but wound up cutting them; there was just nowhere to fit them elegantly into this or any of the subsequent articles.

The book is from a time when a number of prominent science-fiction writers were evangelizing for home computers, but it’s definitely the weirdest specimen of its breed I’ve ever seen. It reads as if Herbert had read the manuals for several home computers, but never actually used one. And, appropriately from an author who banned computers from his own science-fiction universe for impinging on a domain that ought to be reserved for humans alone, it treats computers more as personal and societal enemies to be subdued than tools to be harnessed. In all this, it perhaps reveals more about its author than it does its ostensible subject matter.

Saint Podkayne

November 26, 2018 at 3:29 pm

“Jodorowsky’s Dune” is a documentary absolutely worth watching. I’ve watched other documentaries about Jodorowsky, and nobody else managed to do one where Jodorowsky isn’t not only the star of the show, but also the one dictating the emotional conclusions. “Jodorowsky’s Dune” shows us exactly how charming he is, how his own messiah complex operates, lets his family speak, provides us with a narrative thread Jodorowsky himself couldn’t disapprove of… and then makes it clear we’ve just been taken in by a cult leader, same as anybody. The fact that it’s truly interesting to hear about this movie that never got made just wraps it up perfectly. It’s a truly funny yet creepy film.

Jason

November 27, 2018 at 9:32 am

“He had always conceived of Dune as an epic tragedy in the Shakespearean sense…”

Now I understand why my wife can’t seem to get through Dune Messiah after loving the first novel. “I know something terrible is going to happen,” she says, “and I don’t want to read it.”

She says she’s thinking about skipping to the third book. I guess I’ll tell her to skip them all. :)

As for me, my only experience with Dune is that great, great Adlib soundtrack which I’m sure will merit a mention next week!

Gideon Marcus

November 27, 2018 at 4:20 pm

How very timely! I just finished part 1 of Dune Planet, which came out in Analog this month (55 years ago).

It’s interesting but not very well crafted.

AguyinaRPG

November 28, 2018 at 12:05 am

I never read Dune, but being in the circles that I am, it’s shadow really cannot be escaped. Each of the major sci-fi franchises has a sort of core tenant of human experience inherit to them. Star Wars is about conflict, Star Trek is about exploration, and Dune is about resources. That makes for most of a 4X game!

I do like to joke to people that the film is the greatest ever made just to see their reaction. Personally I like it as a disconnected series of fantastic film-making moments. Never even bothered to really figure out what it was about. There’s nothing wrong in my mind for disassociating the coherent and finding the pieces memorable by themselves. Total stoner movie though.

I do hope you will be covering the Cryo game in some detail rather than just skipping to Dune II. That one is a really great artistic piece in itself. A real forgotten treasure from the early 90s Adventure era.

I would suggest you ring up Alex or I because he obtained a French book which has the Cryo side of the story about the licensing which is very different from how the Westwood people tell it. Either way, I’m looking forward to you tracing the influences and extrapolating the meaning behind their portrayals of the Dune universe.

Carl

November 29, 2018 at 10:25 pm

Nice article, Jimmy. I only read Dune a few years ago and it felt to me at least that it hasn’t aged all that well. All the Islamic and Arabic references must have felt quite exotic in the 1960s and 1970s but most westerners are much more knowledgeable about Muslim culture now. Also, I found the casual homophobia and the fetishization of Baron Harkonnen’s girth a bit off-putting (but remember this is me reading the book from a 2010-ish sensibility).

Also, small correction. When you’re talking about Harkonnen’s costume, “all but buried under 200 pounds of fake silicon flesh as the disgustingly evil “, it should be silicone, not silicon.

Jimmy Maher

November 30, 2018 at 9:24 am

Thanks!

And yeah, I can see and to some extent agree with your point of view. As I said, it’s a book I can respect, but not one I can manage to love.

Roberto

November 30, 2018 at 4:32 pm

Hi. “De Laurentis”, with just one I (There are no double vocals in any Italian word, actually).

Jimmy Maher

November 30, 2018 at 11:42 pm

It looked strange to me as well, but that’s definitely the spelling, at least in the English-speaking world: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dino_De_Laurentiis.

Roberto

December 4, 2018 at 8:14 pm

Yes, you’re right! I’ve seen his name hundreds of times on screen, yet I was convinced it was Laurentis! So, actually Italian proper names can have double vocals, I didn’t know this. Sorry for wasting your time!

Doug Orleans

December 4, 2018 at 6:53 pm

Perhaps worth a footnote is the Dune board game, created by the guys who made Cosmic Encounter and published by Avalon Hill in 1979 (with a reissue in 1984 to tie in with the movie). It’s a well-regarded strategy game: https://www.boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/121/dune

Tom

December 22, 2018 at 12:29 am

When the movie came out, I was in college and had read the 3 books twice. God Emperor of Dune came out after a gap. There was even a preview of it in Playboy along with an interview with Herbert.

That, along with the rest in the series, was all about the consequences and undoing its effects on humans.

As a fan, I’ve read all the Anderson ones (Vermillion Hells!). The 1st trilogy were crap. I though the others were ok and fleshed out some of the backstory the lead up to the books. I was surprised at how bad those 3 were. I’ve read other books by Brian Herbert and liked them well enough.

Cheshire Noir

May 3, 2019 at 5:41 am

Years ago at a small SciFi con we were discussing “worst movies” at a panel and someone mentioned Dune.

Someone in the crowd popped up with “I liked Dune! But I was on Acid at the time.”

The room split nearly perfectly down the middle into two groups, one discussing how amazing Dune was under the influence of LSD with the other half wondering exactly what they had missed out on.

Good times…

Wolfeye M.

October 24, 2019 at 3:39 am

I read the Dune books, and, well, let’s just say that the first one I’ve read many times, the rest, not so much. But, then, I’m not a fan of Shakespearean Tragedies, so that’s probably why Dune is my favorite of the bunch, while the rest of the series goes unread. Also, the quality of the writing did seem to go downhill as the series went on. But, that said, it’s sad that Frank died before he got to cap off the books, if he intended to write more after God Emperor.

As for the books written by his son and Kevin J. Anderson…well, Brian isn’t a Christopher Tolkien. I remember enjoying KJA’s Star Wars books well enough. But, their Dune books just were too dense and didn’t make much sense. I gave up after reading two of them.

I enjoyed the movie, it’s one of my favorites. I think it’s more appreciated now than it was when it first came out.

killias2

September 18, 2021 at 3:43 pm

First off, it feels oddly appropriate to arrive at this point in the chronology right before the newest attempt at a Dune movie arrives. Here’s hoping they pulled it off this time!

Second, I loved the movie as a kid, and I loved the first book as an adult. The second book… I have a bunch of issues with it. It’s a very thin and focused book, in addition to tragic, which makes it contrast sharply against the big, epic, heroism of the first. The third is quite good, but it starts to feel like its own thing. I read the fourth and.. stopped after that. The first book is the only real requirement.

The movie has all manner of issue, but, if you like it, it’s hard to find anything else quite like it.

Jeff Nyman

January 16, 2022 at 8:33 pm

I honestly thought I would get through one of these posts without finding something like this:

“As for the flood of more recent Dune novels, written by Frank Herbert’s son Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson, previously a prolific author of X-Files and Star Wars novels and other low-hanging fruit of the literary landscape: stay far, far away.”

Or, rather perhaps, read the books for yourselves and judge for yourselves. Elitist stances rarely go with historical writing. It’s objectively true to say that the focus of the newer Dune books is very different from the originals. Which is not at all to say the books are inherently bad. In fact, just as Dune had many detractors as it did supporters, the same applies to the newer works in the series.

Mean-spirited comments in articles like these detract from the content. Examples:

“…starring a buff if nearly inarticulate former bodybuilding champion named Arnold Schwarzenegger;…”

“…with flotsam washed up from the more dissipated end of the celebrity pool:”

For an objective reader, none of this sounds like clever writing.

“They went bankrupt in the aftermath of its failure…”

Dune is not what caused their bankruptcy at all, which is what this sort of implies. It was a string of failures along with a poorly thought of subsidiary/spinoff company that did them in. It wasn’t until 14 more films that the state of their financial problems became very clear. The company as a whole filed for bankruptcy on 16 August 1988. (There was the Italian studio Dinocitta, which was founded by Dino De Laurentiis, that also went bankrupt much earlier.)