While the broth of Ultima Online was slowly thickening, not one but two other publishers beat EA and Origin Systems to the punch by releasing graphical persistent virtual worlds of their own. We owe it to them and to ourselves to have a look at these other POMG pioneers before we return to the more widely lauded one that was being built down in Texas. They were known as Meridian 59 and The Realm.

Meridian 59 was inspired by Scepter of Goth,[1]The first word in the name is often spelled Sceptre as well. a rare attempt to commercialize the text-only MUD outside of the walled gardens of online services such as CompuServe and GEnie. After a long gestation period on a mainframe of the Minnesota Educational Computer Consortium, it was ported in 1983 to an IBM PC/XT, to which were cabled sixteen modems and sixteen phone lines, one for each of the players who could be online at any given time. A company called InterPlay — no, not that Interplay — franchised the software out to operators in at least seven American cities. These franchisees then charged their customers an hourly fee to roam around inside the world. The business model worked surprisingly well for a couple of years, until InterPlay’s founder was sent to prison for tax evasion and his company went down with him.

During the fairly brief window of time that Scepter of Goth remained a going concern, a pair of brothers named Andrew and Chris Kirmse fell in love with the incarnation of it that was run out of their hometown of Fairfax, Virginia. Not yet teenagers when they discovered it, they never forgot it after it disappeared. In the summer of 1994, when Andrew had just earned his bachelor’s degree from MIT and Chris had just finished his junior year at Virginia Tech, they set about bringing something similar to life, albeit this time with a top-down graphical view of the world rather than scrolling text. By the end of the year, they felt they had “the foundation of a game,” as Andrew puts it.

A very early version of the game that would evolve into Meridian 59. At this point, it was known as Blackstone.

Then, like so many other young men of their generation and disposition, they found their productivity derailed by a little game called DOOM. “I spent the early part of 1995 playing DOOM II to the exclusion of all else,” admits Andrew. As soon as he had finished all of the single-player levels, he and a friend started to make a DOOM-like engine of their own — again, just as about a million other young programmers were doing at the time. But there was a key difference in Andrew’s case: he didn’t want to make a single-player game, nor even one oriented toward the one-and-done online deathmatches that were all the rage at university campuses all over the country. He rather wanted to combine DOOM with the persistent online game which he and his brother had already begun — that is to say, to make a DOOM that took place in a persistent world.

Andrew and Chris Kirmse cleared their schedules so that they could spend the summer of 1995 in their parents’ basement, figuring out whether it was possible and practical to make the unholy union a reality. With the Internet now entering the public consciousness in a big way, it was a no-brainer to move the game there, where it would be able to welcome far more than sixteen players without requiring a warehouse worth of modems. A handful of other young dreamers joined them as partners in a would-be company called Archetype Interactive, contributing art, world designs, and even a modicum of business acumen from locations all over the country. Like Kali and for that matter DOOM itself, it was the very definition of an underground project, springing to life far from the bright lights of the major publishers, with their slick “interactive movies” and their fixed — and, it would turn out, comprehensively wrong — ideas of the direction mainstream gaming was destined to go. At first the Archetypers wanted to call their game Meridian, simply because they thought the word sounded cool. But they found that the name was already trademarked, so they stuck an arbitrary number at the end of it to wind up with Meridian 59.

By December, they had a bare-bones world with, as Andrew Kirmse says, “no character advancement, no spells, no guilds, no ranged weapons, just the novelty of seeing other people walking around in 3D and talking to them.” Nevertheless, they decided they were ready for an alpha test, several months before Ultima Online would reach the same milestone. They fired up the server late one evening and went to bed, and were thrilled to wake up the next morning and find four people — out of a maximum of 35 — poking around in their world at the same time. Andrew still calls the excitement of that moment “the high point of the entire project.” They redoubled their efforts, roping in more interested observers to provide more art and expand upon the world and its systems, pushing out major updates every few weeks.

In an testament to the endearingly ramshackle nature of the whole project, the world of Meridian 59 was built using a hacked DOOM level editor. Likewise, much of the early art was blatantly stolen from DOOM.

The world went into beta testing in April of 1996. The maximum number of concurrent players had by now been raised by an order of magnitude, but Meridian 59 had become popular enough that the Archetypers still had to kick people out when they needed to log on themselves to check out their handiwork. Among the curious tire-kickers who visited was Kevin Hester, a programmer with The 3DO Company. Founded by Trip Hawkins five years earlier with the intention of bringing a “multimedia console” — don’t call it a games console! — to living rooms everywhere, 3DO was rather at loose ends by this point, having banked on a future of digital entertainment that was badly at odds with the encroaching reality. But Hawkins’s latest instincts were sounder than those of a half-decade previous: he had now decided that online play rather than single-player multimedia extravaganzas was the future. He jumped on Meridian 59 as soon as Hester brought it to his attention, putting together in a matter of days a deal to acquire the budding virtual world and its far-flung network of creators for $5 million in 3DO stock. The Archetypers all signed on the dotted line and moved to Silicon Valley, most of them meeting one another face to face for the first time on their first day in their new office, where they were thrilled to find five servers — enough for five separate instances of their virtual world! — just waiting for them to continue with the beta test.

It had started off like a hacker fairy tale, but the shine wore off quickly enough. Inspired by the shareware example of DOOM, the Kirmse brothers had expected to offer the game client as a free download, with the necessity to pay subscription fees kicking in only after players had been given a few hours to try it out. 3DO vetoed all of this, insisting that the client be made available only as a boxed product with a $50 initial price tag, plus a $15 monthly subscription fee. And instead of being given as much time as they needed to make their new world fit for permanent habitation, as they had been promised they would, the Archetypers were now told that they had to begin welcoming paying customers into Meridian 59 in less than three months. Damion Schubert, Meridian 59‘s world-design lead, claims that “3DO was using us to learn about the business of online gaming,” seeing their very first virtual world as a stepping-stone rather than a destination unto itself. Whatever the truth of that assertion, it is a matter of record that, while the Archetypers were trying to meet 3DO’s deadline, the stock they had been given was in free fall, losing 75 percent of its value in those first three months, thereby doing that much more to convince the accountants that Meridian 59 absolutely, positively had to ship before 3DO’s next fiscal year began on October 1.

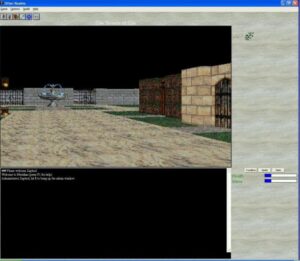

So, the game that was officially released on September 27, 1996, was not quite the one the Kirmses had envisioned when they signed the contract with 3DO. To call it little more than a massively-multiplayer DOOM deathmatch with a chat system grafted on would be unkind but not totally unfair. Its pseudo-3D engine would have looked badly outdated in 1996, the year of Quake, even if the art hadn’t been such a mismatched grab bag of aesthetics and resolutions. Meridian 59 evinced none of the simulational aspirations of Ultima Online; this was not a world in which anyone was going to pass the time baking bread or chopping lumber. For lack of much else to do, people mostly occupied themselves by killing one another. Like Ultima Online, the software permitted player-versus-player combat anywhere and everywhere; unlike Ultima Online, there were no guards patrolling any of the world’s spaces to disincentivize it. A Meridian 59 server was a purely kill-or-be-killed sort of world, host to a new war every single day. Because there was no budget to add much other content to the world, this was just as well with its creators; indeed, they soon learned to lean into it hard. Activities in the world came to revolve around the possession of guild halls, of which each server boasted ten of varying degrees of splendor for the disparate factions to fight over. If you didn’t like to fight with your fellow players more or less constantly, Meridian 59 probably wasn’t the game for you.

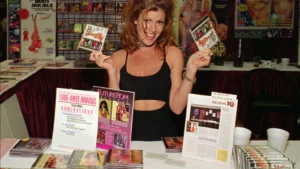

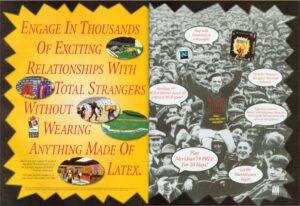

Handed the first-ever full-fledged massively-multiplayer online role-playing game, 3DO’s marketers chose to… write non-sequiters about latex. This might be the worst advertisement I’ve ever seen; I literally have no idea what joke it’s trying and failing to land. Something about condoms, I presume?

Luckily, there were plenty of gamers who really, really did like to fight, as the popularity of DOOM deathmatches illustrated. Despite its dated graphics and despite promotional efforts from 3DO that were bizarrely inept when they weren’t nonexistent, Meridian 59 managed to attract 20,000 or more subscribers and to retain them for a good while, keeping all ten of the servers that were given over to it after the beta test humming along at near capacity most of the time. 3DO even approved a couple of boxed expansion packs that added a modicum of additional content.

But then, in late 1997, 3DO all but killed the virtual world dead at a stroke. Deciding it was unjust that casual players who logged on only occasionally paid the same subscription fee as heavy users who spent many hours per day online, they rejiggered the pricing formula into a tangle of numbers that would have baffled an income-tax accountant: $2.49 per day that one logged on, capped at $9.99 per week, with total fees also capped at $29.99 per month. But never mind the details. Since the largest chunk of subscribers by far belonged to the heavy-user category, it boiled down to a doubling of the subscription price, from $15 to $30 per month. The populations on the servers cratered as a result. Meridian 59‘s best days — or at least its most populous ones — thus passed into history.

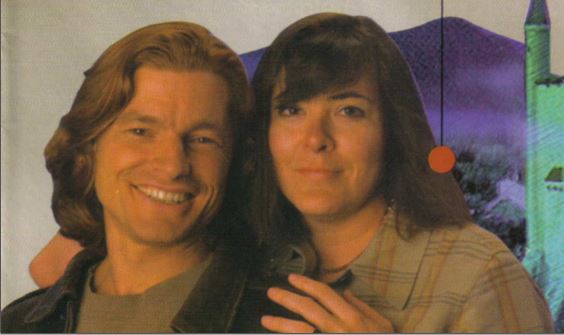

The other graphical MMORPG to beat Ultima Online to market had a very different personality. Sierra’s The Realm was the direct result of Ken Williams’s musings about what an “online adventure game” might be like, the same ones that I quoted at some length in my last article. After trying and failing to convince Roberta Williams to add a multiplayer option to King’s Quest VII, he went to a programmer named David Slayback, saying, “Wouldn’t it be cool if we could do something like our adventure games, that was Medieval themed, and allowed players to swap items with each other, buy weapons, and attack monsters?” Slayback then took the ball and ran with it; as Ken himself acknowledges, that initial conversation was “the limit of my involvement creatively.”

The original plan was for The Realm to become a part of America Online, the great survivor of the pre-Web era of commercial online services. That deal, however, fell through. Meanwhile Sierra was itself acquired by an e-commerce firm called CUC International, and The Realm seemed to fall between two stools amidst the reshuffling of deck chairs that followed. A beta test in the summer of 1996 did lead to the acceptance of the first paying subscribers in December of that year, but Sierra never did any real promotion beyond its own customer magazine, making the client software available only via mail order. Still, by all indications this virtual world attracted a number of players comparable to that of Meridian 59, perhaps not least because in its case buying the boxed client entitled the customer to a full year of free online play.

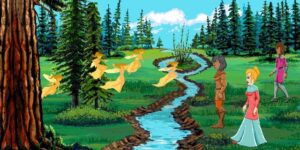

The Realm stands today as a rather fascinating artifact, being the road largely not taken in the MMORPG space. In presentation, aesthetics, and culture, it has more in common with Habitat, an amazingly early attempt by Lucasfilm Games and America Online’s direct predecessor Quantum Link to build a non-competitive graphical space for online socializing, than it does with either Meridian 59 or Ultima Online. This world was very clear about where its priorities lay: “The Realm offers you a unique environment in which to socialize with online friends (or make some new ones) and also gives you something fun to do while you’re socializing.” It was, in other words, a case of social space first, game second. As such, it might be better read as a progenitor to the likes of Second Life or The Sims Online than something like World of Warcraft.

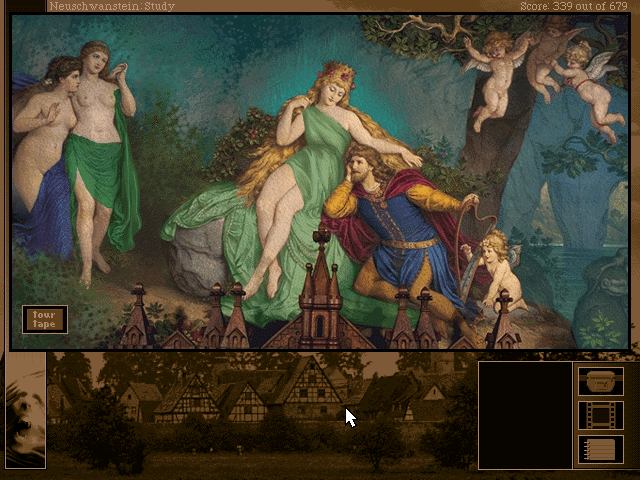

Each player started in her own house, which she had to fight neither to acquire nor to defend. The interface was set up like one of the point-and-click graphic adventures that had been Sierra’s bread and butter since the mid-1980s, with the player guiding her avatar in the third person across a map made up of “rooms” that filled exactly one screen each. The graphical style too was right out of King’s Quest. None of this is terribly surprising, given that The Realm was built using SCI, Sierra’s venerable adventure-game engine.

Although there were monsters to fight and treasure to collect, player-versus-player combat was impossible. Even profanity was expressly forbidden. (“This includes ‘masking’ by using asterisks as part of the word,” noted the FAQ carefully.) The combat was also unusual in that it was turn-based. This choice, combined with the way that The Realm off-loaded an unusual amount of work to the player’s local client, meant that Sierra didn’t have to spread it across multiple servers; uniquely for this era, there really was just one Realm.

All of this attracted a dramatically different clientele from that of Meridian 59; many more women hung out in The Realm, for one thing. Interior decoration and fashion trumped murder and theft in the typical range of pursuits. Beth Demetrescu wrote in Sierra’s magazine InterAction about her own first days there:

As with all newbies, I started in my house. I was a poor, hungry, fashion faux pas. After I got out of my house, moved about six screens, and was lost in my hometown, I encountered HorseWoman, whose biography said she was an eleven-year-old. She took me to her home, gave me decent clothes, and taught me about basic communication, navigation, and combat. This was my first experience with the warm, welcoming community of The Realm.

I soon found myself outside of the town fighting rats. There are plenty of large, ferocious beasts to fight, but for the time being, all I could handle were rats. I was really worried the first time one of these rats killed me, thinking I was going to get kicked out of the game and would have to log back on. Instead, I lost everything I was carrying, but I was found by wanderers who dragged me home to heal…

I learned of Realm weddings. BlueRose, the Justice of the Peace, often called the Lady of Love, conducts over half of the Realm weddings…

I have picked up several valuable things from the many Realmers I have encountered. Not only did I get important information on The Realm’s features and inhabitants, but I also learned from their example about The Realm’s vast, multinational community. These people are friendly and helpful.

The contrast with Meridian 59, where a bewildered newbie was more likely to be given a broadsword to the back of the neck than navigational and sartorial assistance, could hardly have been greater.

All told, then, Meridian 59 and The Realm provided the early MMORPG space with its yang and its yin: the one being a hyper-violent, hyper-competitive free-for-all where pretty much anything went, the other a friendly social space that was kept that way by tight moderation. Nevertheless, the two did have some things in common. Neither ever became more than moderately popular, for one — and that according to a pretty generous interpretation of “moderately” in a fast-expanding games industry. And yet both proved weirdly hard to kill. In fact, both are still alive to this day, abandoned decades ago by their original publishers but kept online by hook or by crook by folks who simply refuse to let them go away — certainly not now, when the aged code that makes their worlds come alive can be run for a pittance on a low-end server tucked away in some back corner of an office or data center somewhere. Their populations on any given evening may now be in the dozens rather than the hundreds or thousands, but these virtual worlds abide. In this too, they’ve set a precedent for their posterity; the Internet of today is fairly littered with online games whose heyday of press notices and mainstream popularity are well behind them, but that seem determined to soldier on until the last grizzled graybeard who cut his teeth on them in his formative years shuffles off this mortal coil. MMORPGs especially are a bit like cockroaches in this respect — with no insult to either the worlds or the insects in question intended. Suffice to say that community can be a disarmingly resilient thing.

But we return now to the story of Ultima Online, whose makers viewed the less than overwhelming commercial acceptance of Meridian 59 and The Realm with some ambivalence. On the one hand, Ultima Online had avoided having its own thunder stolen by another MMORPG sensation. On the other, these other virtual worlds’ middling trajectories gave no obvious reason to feel hugely confident in Ultima Online‘s own commercial prospects.

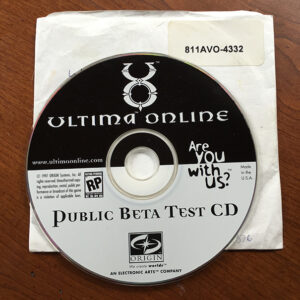

This was a problem not least because, as 1996 turned the corner into 1997, the project’s financial well had just about run dry, just as this virtual Britannia was ready to go from the alpha to the beta stage of testing, with ten to twenty times the number of participants of earlier testing rounds. It wasn’t clear how this next step could be managed under the circumstances; the client software was by now too big to ask prospective testers to download it in its entirety in this era of dial-up connections, yet there simply wasn’t sufficient money in the budget to stamp and ship 20,000 or more CDs out to them. The team decided there was only one option, cheeky though it seemed: to ask each participant in effect to pay Origin for the privilege of testing their game for them, by sending in $5 to cover the cost of the CD. The principals claim today that 50,000 people did so as soon as the test was announced online, burying Origin in incoming mail; I suspect this number may be inflated somewhat, as many of those associated with Ultima Online tend to be in the memories of those who made it. But regardless of the exact figure, the response definitely was considerable, not to mention gratifying for the little team of ex-MUDders who had been laboring in disrespected obscurity up there on a gutted fifth floor. It was the first piece of incontrovertible evidence that there were significant numbers of people out there who were really, really excited by the idea of living out an Ultima game with thousands of others.

As the creators tell the story, the massive popular reaction to the call for beta testers was solely responsible for changing the hearts and minds of their managers at EA and Origin. Realizing suddenly that Ultima Online had serious moneymaking potential, they went overnight from passive-aggressively trying to kill it to being all-in with bells on. In March of 1997, they moved the MUDders from their barren exile down to the scene of the most important action at Origin, where a much larger team had been working on Ultima IX, the latest iteration in the single-player series. Yet it was the latter project that was now to go on hiatus, not Ultima Online. This new amalgamation of developers, five or six times the size of the team of the day before, had but one mandate: get the virtual world done already. After two years of living hand to mouth, the original world-builders had merely to state their wishes in terms of resources in order to see them granted.

Most of the conceptual work of building this new online world had already been done by the time the team was so dramatically expanded. Still, we shouldn’t dismiss the importance of this sudden influx of sometimes unwilling bandwagon jumpers. For they made Ultima Online look like at least a passable imitation of a AAA prestige project, in a way that Meridian 59 and The Realm did not. A high design standard combined with a relatively high audiovisual one would prove a potent combination.

With its isometric perspective, Ultima Online most resembled Ultima VII in terms of presentation. The graphics were by no means cutting-edge — Ultima VII had come out back in 1992, after all — but they were bright and attractive, without going full-on cartoon like The Realm.

Did all of this really happen simply because the response to the call for beta testers was better than expected? I have no smoking gun either way, but I must say that I tend to doubt it. Just about everyone loves a good creatives-versus-suits story, such that we seldom question them. Yet the reasoning that went on in the executive suites prior to this turnaround in Ultima Online‘s fortunes was perhaps a little more complex than that of a pack of ravenous wolves chasing a tasty rabbit that had finally been revealed to their unimaginative minds. Whatever else one can say about them, most of the suits didn’t get where they were by being stupid. So, maybe we should try to see the situation from their perspective — try to see what Origin looked like to the outsiders at EA’s California headquarters.

Throughout the 1990s, Origin lived on two franchises: Richard Garriott’s Ultima and Chris Roberts’s Wing Commander. To be sure, there were other games here and there, some of which even turned modest profits, but it was these two series that kept the lights on. When EA acquired Origin in September of 1992, both franchises were by all indications in rude health. Wing Commander I and II and a string of mission packs for each were doing tremendous numbers. Ultima VII, the latest release in Richard Garriott’s mainline series, had put up more middling sales figures, but it had been rescued by the spinoff Ultima Underworld, which had come out of nowhere — or more specifically out of the Boston-based studio Blue Sky Productions, soon to be rebranded as Looking Glass — to become another of the year’s biggest hits.

Understandably under the circumstances, EA overlooked what a dysfunctional workplace Origin was already becoming by the time of the acquisition, divided as it was between two camps: the “Friends of Richard” and the “Friends of Chris.” Those two personifications of Origin’s split identity were equally mercurial and equally prone to unrealistic flights of fancy; one can’t help but sense that both of their perceptions of the real world and their place in it had been to one degree or another warped by their having become icons of worship for a cult of adoring gamers at an improbably young age. Small wonder that EA grew concerned that there weren’t enough grounded adults in the room down in Austin, and, after first promising a hands-off approach, showed more and more of a tendency to micro-manage as time went on — so much so that, as we learned in the last article, Garriott was soon reduced to begging for money to start his online passion project.

Wing Commander maintained its momentum for quite some time after the acquisition, even after DOOM came along to upend much of the industry’s conventional wisdom with its focus on pure action at the expense of story and world-building, the things for which both Garriott and Roberts were most known. Wing Commander III was released almost a year after DOOM in late 1994 with a cast of real actors headed by Mark Hamill of Star Wars fame, and became another huge success. Ultima, however, started to lose its way almost as soon as the ink was dry on the acquisition contract. Ultima VIII, which was also released in 1994, chased the latest trends by introducing a strong action element and simplifying most other aspects of its gameplay. This was not done, as some fan narratives wish to state, at the behest of EA’s management, but rather at that of Richard Garriott himself, who feared that his signature franchise was at risk of becoming irrelevant. That said, EA can and should largely take the blame for the game being released too early, in a woefully buggy and unpolished state. The critical and commercial response was nothing short of disastrous, leaving plenty of blame to go around. Fans complained that Ultima VIII had more in common with Super Mario Bros. than the storied Ultima games of the past, bestowing upon it the nickname Super Avatar Bros. in a backhanded homage to the series’s most hallowed incarnation, 1985’s Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, whose unabashed idealism now seemed like something from a lifetime ago in a parallel universe.

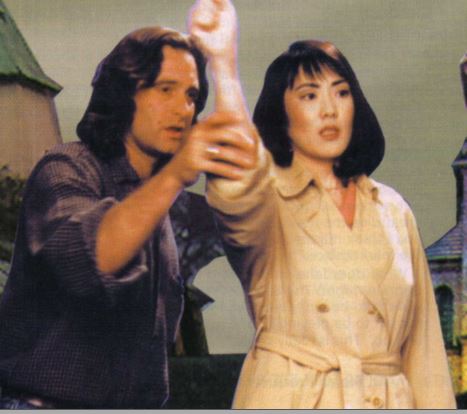

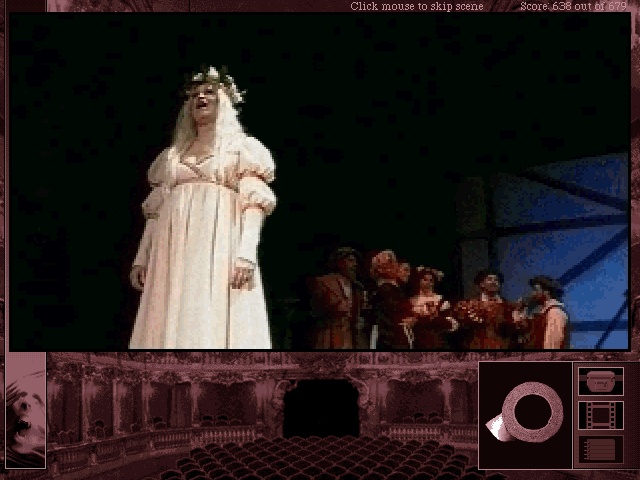

Then, in early 1996, Origin’s other franchise went squishy as well. As the studio’s own press releases breathlessly trumpeted, Wing Commander IV was the most expensive digital game ever made to that date, with a claimed production budget of $12 million. The vast majority of that money went into a real Hollywood film shoot, directed by Chris Roberts himself and starring a returning Mark Hamill among a number of other recognizable faces from the silver screen. Wing Commander IV wound up costing four times as much as its predecessor and selling half as many copies, taking months of huffing and puffing to just about reach the break-even point. The interactive-movie era had reached the phase of diminishing returns; under no circumstances was EA going to let Origin make a game like this one again.

But what kinds of games should Origin be making? That was the million-dollar question in the aftermath of Wing Commander IV. After Chris Roberts left the studio to pursue his dream of becoming the latest George Lucas in Hollywood, Origin announced that his series was to be continued on a less grandiose scale, moving some of the focus away from the cut scenes and back to the gameplay. Yet there was no reason to believe such games would make many inroads beyond the hardcore Wing Commander faithful. Meanwhile Richard Garriott had pledged to repair the damage done by Ultima VIII, by making the next single-player Ultima the biggest, best one ever. But epic CRPGs in general had been in the doldrums for years, and the Ultima IX project was already showing signs of becoming another over-hyped, over-expensive boondoggle like Wing Commander IV. Exacerbating the situation was the loss of two of the only people at Origin who had shown themselves to be capable of restraining and channeling Garriott’s flights of fancy. Origin and EA alike felt keenly the loss of the diplomatic and self-effacing designer and producer Warren Spector, the first everyday project lead on Ultima IX, who decamped to Looking Glass in 1995 when that project was still in its infancy. Ditto the production manager Dallas Snell, a less cuddly character whose talent for Just Getting Things Done — by cracking heads if necessary — was almost equally invaluable.

Of course, one can still ding EA for failing to see that Richard Garriott was onto something with Ultima Online long before they did. In their partial defense, though, Garriott tended to propose a lot of crazy stuff. As his checkered post-millennial career in game development illustrates all too clearly, he has not been a detail-oriented creator since his days of conceiving and coding the early Ultima games all by himself. This has made his ideas — even his good ones, which Ultima Online certainly was — all too easy to dismiss.

Nonetheless, the potential of persistent online multiplayer gaming was becoming impossible to deny by early 1997, what with the vibrant virtual communities being built on the likes of Kali and Battle.net, in addition to the smaller but no less dedicated ones that had sprung up in Meridian 59 and The Realm. You’d have to be a fool not to be intrigued by the potential of Ultima Online in a milieu such as this one — and, again, EA’s executives most definitely weren’t fools. They wanted to keep Origin alive and viable and relevant as badly as anyone else. Suddenly this seemed the best way to do so. Thus the mass personnel transfer from Ultima IX, which was increasingly smelling like gaming’s past, into Ultima Online, which had the distinct whiff of its future.

It was a difficult transition for everyone, made that much more difficult by the fact that most of the people involved were still in their twenties, with all of the arrogant absolutism of youth. Both the project’s old-timers and its newcomers had plenty of perfectly valid complaints to hurl at their counterparts. Raph Koster, who had been told that he was the design lead, was ignored by more experienced developers who thought they knew better. And yet he did little for his cause by, as he admits today, “sulking and being very rude” and “behaving badly and improperly” even to Richard Garriott himself. From his point of view, the newcomers showed that they fundamentally didn’t understand online games when they wasted their time on fluff that players who needed to be captured for months or years would burn through in a matter of hours, such as lengthy, single-player-Ultima-style conversation trees for the non-player characters. Yet the newcomers were right to express shock and horror when they found that, amidst all the loving attention that had been given to simulating Britannia’s ecology and the like, no one on the original team had thought up a consistent system for casting spells, a bedrock of Ultima‘s appeal since the very beginning. Even today, one Ultima IX refugee accuses the MUDders of being “focused on minutia, what I would call silly little details that really added nothing to the game.”

When the two-month-long beta test finally began after repeated delays in June of 1997, the dogged simulation-first mentality of Koster and company faced a harsh reckoning with reality. Many of the systems that had seemed wonderful in theory didn’t work in practice, or displayed side effects that they’d never anticipated. Here as in many digital games, attempting to push the simulation too far just plunged the whole thing into a sort of uncanny valley, making it feel more rather than less artificial. For instance, the MUDders had made it possible for you to learn or improve skills simply by standing in close proximity to someone who was using the skill in question at a high level, on the assumption that your character was observing and internalizing this example of a master at work. But they’d also instituted a cap on the total pool of skill points a character could possess across all disciplines, on the assumption that no Jack of all trades could be a master of them all; just as is the case for most of us in real life, in Ultima Online you could be really good at a few things, or fair at a lot of them, but not really good at a lot of them. When a character hit her skill-point cap, learning new things would cause some of her other skills to decline to stay under it. In practice, this caused players to desperately try to avoid seeing what that baker or weaver was doing, for fear of losing their ability to hunt or cast spells as a result. Problems like these hammered home again and again the fact that any digital simulation is only the crudest approximation of a lived existence; in the real world, matters are not quite so zero-sum as instantly losing the ability to catch a fish because one has learned to cook a fish.

But the most extreme case of unforeseen consequences involved the aforementioned lovingly crafted ecology of virtual Britannia. To put it bluntly, the players destroyed it — all of it, within days if not hours. The population of deer and rabbits, the food sources of apex predators like dragons, were slaughtered to extinction by players instead. This was not done out of sheer bloody-mindedness alone, although that was undoubtedly a part of the equation. The truth was that deer and rabbits had value, in the form of meat and pelts. In a sense, then, virtual Britannia was becoming a real economy, just as its creators had always hoped it would. But it was an economy without real-world limits or controls, unimpeded by consequences which were themselves only virtual, never real; no one was going to go hungry in real life for over-hunting the forests and fields of Britannia. The same went for trees and fish and a hundred other precious resources that we of the real world usually make some effort to conserve, however imperfectly. With the simulation spinning wildly out of control, Origin had to start putting its thumb on the scales, applying external remedies such as magically re-spawning rabbits and trees, lest the world degenerate into a post-apocalyptic wasteland, a deserted moonscape where roving bands of starving players were chased hither and yon by equally hungry dragons. People came to an Ultima game expecting a Renaissance Faire version of Merry Olde England, not a Harlan Ellison story.

Of course, the external corrections themselves had further knock-on consequences. By creating an endless supply of animals to hunt and trees to fell, Origin was in effect giving the economy a massive, perpetual external stimulus. The overseers were therefore always on the lookout for ways to suck gold back out of the world. Ironically, one of the best was to let players get killed a lot, since between death and resurrection they lost whatever money they’d been carrying with them. Thus Origin had a perverse incentive not to try too hard to make Britannia a safer, more friendly place.

Such collisions between idealism and reality were scarring for the MUDders. “This was a wake-up call for me,” says Raph Koster. “The limits on what we can get an audience to go along with, and how much we can affect the bottom line. A lot of people [on the development team] were emotionally hurt by the player killing. Many of the tactics we would use on MUDs just didn’t work at a large scale. Players behaved differently. They were ruder to one another.” All of which is to say that Richard Garriott’s fondly expressed wish that the persistent quality of Ultima Online would serve to put a brake on the more toxic ways of acting out on the anonymous Internet did not come to pass to anything like the extent he had imagined.

At the same time, though, it wasn’t all destruction and disillusionment during that summer of the beta test. Some players proved less interested in killing than they were in crafting, becoming armorers and blacksmiths, jewelers and merchants, chefs and bankers and real-estate agents. Players cooked food and sold it from booths in the center of the cities or earned a (virtual) living as tour guides, leading groups of people on treks to scenic but dangerous corners of the world. Enterprising wizards set up a sort of long-distance bus service, opening up magical portals to shuttle their fellow players instantly from one side of the world to another for a fee. Many of the surprises of the beta period were just the kind the MUDders had been hoping to see, emerging from the raw simulational affordances of the environment. “[Players] used the ability to dye clothing to make uniforms for their guilds,” says Raph Koster, “and they [held] weddings with coordinated bridesmaids dresses. They started holding sporting events. They founded theater troupes and taverns and police forces.” The agents of chaos may have been perpetually beating at the door, but there was a measure of civilization appearing in virtual Britannia as well.

Or rather in the virtual Britannias. One of the most frustrating compromises the creators had to make was necessitated by, as compromises usually are in game development, the practical limitations of the technology they had to hand. There was no way that any one of the servers they possessed could contain the number of players the beta test had attracted. So, there had to be two virtual Britannias rather than just one, the precursors to many more that would follow. Both Garriott and Koster have claimed to be the one who came up with the word “shards” as a name for these separate servers, each housing its own initially identical but quickly diverging version of Britannia. The name was grounded in the lore of the very early days of Ultima. In Ultima I back in 1981, the player had shattered the Gem of Immortality, the key to the power of that game’s villain, the evil wizard Mondain. It was claimed now that each of the jewel’s shards had contained a copy of the world of Britannia, and that these were the duplicate worlds inhabited by the players of Ultima Online. Rather amusingly, the word “shard” has since become a generalized term for separate but equal server instances, co-opted not only by other MMORPGs but by administrators of large de-centralized online databases of many stripes, most of which have nothing to do with games.

Each shard could host about 2500 players at once. In these days when the nation’s Internet infrastructure was still in a relatively unrefined state, such that latency tended to increase almost linearly with distance, the shards were named after their real-world locations — there was one on each coast in the beginning, named “Atlantic” and “Pacific” — and players were encouraged to choose the server closest to them if at all possible. (Such concerns would become less pressing as the years went by, but to this day Ultima Online has continued the practice of naming its virtual Britannias after the locations of the servers in the real world.)

On the last day of the beta test, there occurred one of the more famous events in the history of Ultima Online, one with the flavor of a Biblical allegory if not a premonition. Richard Garriott, playing in-character as Lord British, made a farewell tour of the shards in the final hours, to thank everyone for participating before the servers were shut down, not to be booted up again until Ultima Online went live as a paid commercial service. Among fans of the single-player Ultima games, there was a longstanding tradition of finding ways to kill Lord British, who always appeared as a character in them as well. People had transplanted the tradition into Ultima Online with a vengeance, but to no avail; acknowledging that even the most stalwart commitment to simulation must have its limits when it comes to the person who signs your paycheck, the MUDders had agreed to provide Lord British with an “invulnerability” flag. As he stood up now before a crowd on the Pacific shard to deliver his valediction, someone threw a fireball spell at him. No matter; Lord British stepped confidently right into the flames. Whereupon he fell over and died. Someone had forgotten to set the invulnerability flag.

If Lord British couldn’t be protected, decided the folks at Origin on the spur of the moment, he must be avenged; in so deciding, they demonstrated how alluring virtual violence could be even to those most dedicated to creating a virtual civilization. Garriott:

It’s amazing how quickly the cloak of civilization can disappear. The word spread verbally throughout the office: let us unleash hell! My staff summoned demons and devils and dragons and all of the nightmarish creatures of the game, and they cast spells and created dark clouds and lightning that struck and killed people. The gamemasters had special powers, and once they realized I had been killed, they were able to almost instantly resurrect Lord British. And I gleefully joined in the revelry. Kill me, will you? Be gone, mortals! It was a slaughter of thousands of players in the courtyard.

It definitely was not the noble ending we had intended.

And while some players enjoyed the spontaneity of this event, others were saddened or hurt by it. When most characters die they turn into a ghost and are transported to a distant place on the map. Then they have to go find their body. So the cost of being killed is a temporary existence as a ghost. In the last three minutes of these characters’ existence, they suddenly found themselves alone, deep in the woods, unable to speak or interact with anyone else. The net result of this mass killing in retaliation for the assassination of Lord British was that not only were all of these innocent people slaughtered, they were also cast out of the presence of the creators at the final moment. As the final seconds trickled down, they desperately tried to get back, but most often failed. The fact that all of us, the creators and the players, were able to turn the last few moments of the beta test into this completely unplanned and even unimagined chaos was proof that we had built something unique, a platform that would allow players to do pretty much whatever they pleased, and that it was about to take on a life — and many deaths — of its own.

After more than two and a half years, during which the face of the games industry around it had changed dramatically and its own importance to its parent company had been elevated incalculably, Ultima Online was about to greet the real world as a commercial product. Whether the last minutes of its existence while it was still officially an experiment boded well or ill for its future depended on your point of view. But, as Richard Garriott says, the one certain thing was uncertainty: nobody knew quite what would happen next. Would Ultima Online be another Meridian 59 or The Realm, or would this be the virtual world that finally broke through? And what would it mean for gaming — and, for that matter, for the real world beyond gaming — if it did?

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Braving Britannia: Tales of Life, Love, and Adventure in Ultima Online by Wes Locher, Postmortems: Selected Essays, Volume One by Raph Koster, Online Game Pioneers at Work by Morgan Ramsay, Through the Moongate, Part II by Andrea Contato, Explore/Create by Richard Garriott, MMOs from the Inside Out by Richard Bartle, and Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings by Ken Williams; Sierra’s customer newsletter InterAction of Spring 1996, Summer 1996, Spring 1997, Summer 1997, Fall 1997, Summer 1998, and Fall 1998; PC Powerplay of November 1996; Next Generation of March 1997.

Web sources include a 2018 Game Developers Conference talk by some of the Ultima Online principals, an Ultima Online timeline at UOGuide, “How Scepter of Goth Shaped the MMO Industry” by Justin Olivetti at Massively Overpowered, David A. Wheeler’s history of Scepter of Goth, “How the World’s Oldest 3D MMO Keeps Cheating Death” by Samuel Axon at Vice, Andrew Kirmse’s own early history of Meridian 59, Damion Schubert’s Meridian 59 postmortem and its accompanying slides from the 2012 Game Developers Conference, and Gavin Annand’s video interview with the Kirmse brothers.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The first word in the name is often spelled Sceptre as well. |

|---|