As we saw in my previous article, Jeff Tunnell walked away from Dynamix’s experiments with “interactive movies” feeling rather disillusioned by the whole concept. How ironic, then, that in at least one sense comparisons with Hollywood continued to ring true even after he thought he’d consigned such things to his past. When he stepped down from his post at the head of Dynamix in order to found Jeff Tunnell Productions and make smaller but more innovative games, he was making the sort of bargain with commercial realities that many a film director had made before him. In the world of movies, and now increasingly in that of games as well, smaller, cheaper projects were usually the only ones allowed to take major thematic, formal, and aesthetic risks. If Tunnell hoped to innovate, he had come to believe, he would have to return to the guerrilla model of game development that had held sway during the 1980s, deliberately rejecting the studio-production culture that was coming to dominate the industry of the 1990s. So, he recruited Kevin Ryan, a programmer who had worked at Dynamix almost from the beginning, and set up shop in the office next door with just a few other support personnel.

Tunnell knew exactly what small but innovative game he wanted to make first. It was, appropriately enough, an idea that dated back to those wild-and-free 1980s. In fact, he and Damon Slye had batted it around when first forming Dynamix all the way back in 1983. At that time, Electronic Arts’s Pinball Construction Set, which gave you a box of (virtual) interchangeable parts to use in making playable pinball tables of your own, was taking the industry by storm, ushering in a brief heyday of similar computerized erector sets; Electronics Arts alone would soon be offering the likes of an Adventure Construction Set, a Music Construction Set, and a Racing Destruction Set. Tunnell and Slye’s idea was for a sort of machine construction set: a system for cobbling together functioning virtual mechanisms of many types out of interchangeable parts. But they never could sell the vaguely defined idea to a publisher, thus going to show that even the games industry of the 1980s maybe wasn’t quite so wild and free as nostalgia might suggest. [1]That, anyway, is the story which both Jeff Tunnell and Kevin Ryan tell in interviews today, which also happened to be the only one told in an earlier version of this article. But this blog’s friend Jim Leonard has since pointed out the existence of a rather obscure children’s game from the heyday of computerized erector sets called Creative Contraptions, published by the brief-lived software division of Bantam Books and created by a team of developers who called themselves Looking Glass Software (no relation to the later, much more famous Looking Glass Studios). It’s a machine construction set in its own right, one which is strikingly similar to the game which is the main subject of this article, even including some of the very same component parts, although it is more limited in many ways than Tunnell and Ryan’s creation, with simpler mechanisms to build out of fewer parts and less flexible controls that are forced to rely on keystrokes rather than the much more intuitive affordances of the mouse. One must assume that Tunnell and Ryan either reinvented much of Creative Contraptions or expanded on a brilliant concept beautifully in the course of taking full advantage of the additional hardware at their disposal. If the latter, there’s certainly no shame in that.

Still, the machine-construction-set idea never left Tunnell, and, after founding Jeff Tunnell Productions in early 1992, he was convinced that now was finally the right time to see it through. At its heart, the game, which he would name The Incredible Machine, must be a physics simulator. Luckily, all those years Kevin Ryan had spent building all those vehicular simulators for Dynamix provided him with much of the coding expertise and even actual code that he would need to make it. Ryan had the basic engine working within a handful of months, whereupon Tunnell and anyone else who was interested could start pitching in to make the many puzzles that would be needed to turn a game engine into a game.

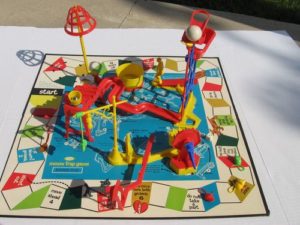

If Pinball Construction Set and those other early “creativity games” were one part of the influences that would result in The Incredible Machine, the others are equally easy to spot. One need only glance at a screenshot to be reminded of the old children’s board game cum toy Mouse Trap, a simplistic exercise in roll-and-move whose real appeal is the elaborate, Rube Goldberg-style mechanism that the players slowly assemble out of plastic parts in order to trap one another’s pieces — if, that is, the dodgy contraption, made out of plastic and rubber bands, doesn’t collapse on itself instead. But sadly, there’s only one way to put the mousetrap’s pieces together, making the board game’s appeal for any but the youngest children short-lived. The Incredible Machine, on the other hand, would offer the opportunity to build a nearly infinite number of virtual mousetraps.

In contrast to such venerable inspirations, the other game that clearly left its mark on The Incredible Machine was one of the hottest current hits in the industry at the time the latter was being made. Lemmings, the work of a small team out of Scotland called DMA Design, was huge in every corner of the world where computer games were played — a rarity during what was still a fairly fragmented era of gaming culture. A level-oriented puzzle game of ridiculous charm, Lemmings made almost anyone who saw it want to pick up the mouse and start playing it, and yet managed to combine this casual accessibility with surprising depth and variety over the course of 120 levels that started out trivial and escalated to infuriating and beyond. Its strong influence can be seen in The Incredible Machine‘s similar structure, consisting of 87 machines to build, beginning with some tutorial puzzles to gently introduce the concepts and parts and ending with some fiendishly complex problems indeed. For that matter, Lemmings‘s commercial success, which proved that there was a real market for accessible games with a different aesthetic sensibility than the hardcore norm, did much to make Sierra, Dynamix’s new owner and publisher, enthusiastic about the project.

Like Lemmings, the heart of The Incredible Machine is its robust, hugely flexible engine. Yet that potential would have been for naught had not Tunnell, Ryan, and their other associates delivered a progression of intriguing puzzles that build upon one another in logical ways as you learn more and more about the engine’s possibilities. One might say that, if the wonderful engine is the heart of the game, the superb puzzle design is the soul of the experience — just as is the case, yet again, with Lemmings. In training you how to play interactively and then slowly ramping up the challenge, Lemmings and The Incredible Machine both embraced the accepted best practices of modern game design well before they had become such. They provide you the wonderful rush of feeling smart, over and over again as you master the ever more complex dilemmas they present to you.

To understand how The Incredible Machine actually works in practice, let’s have a look at a couple of its individual puzzles. We’ll begin with the very first of them, an admittedly trivial exercise for anyone with any experience in the game.

Each puzzle begins with three things: with a goal; with an incomplete machine already on the main board, consisting of some selection of immovable parts; and with some additional parts waiting off on the right side of the screen, to be dragged onto the board where we will. In this case, we need to send the basketball through the “hoop” — which is, given that there is no “net” graphic in the game’s minimalist visual toolkit, the vaguely hole-shaped arrangement of pieces below and to the right of where the basketball stands right now. Looking to the parts area at the far right, we see that we have three belts, three hamster wheels, and three ramp pieces to help us accomplish our goal. The score tallies at the bottom of the screen have something or other to do with time and number of puzzles already completed, but feel free to do like most players and ignore them; the joy of this game is in making machines that work, not in chalking up high scores. Click on the image above to see what happens when we start our fragment of a machine in its initial state.

Not much, right? The bowling ball that begins suspended in mid-air simply falls into the ether. Let’s begin to make something more interesting happen by putting a hamster cage below the falling ball. When the ball drops on top of it, the little fellow will get spooked and start to run.

His scurrying doesn’t accomplish anything as long as his wheel isn’t connected to any other parts. So, let’s stretch a belt from the hamster wheel to the conveyor belt just above and to its right.

Now we’re getting somewhere! If we put a second hamster wheel in the path of the second bowling ball, and connect it to the second conveyor belt, we can get the third bowling ball rolling.

And then, as you’ve probably surmised, the same trick can be used to send the basketball through the hoop.

Note that we never made use of the three ramp pieces at our disposal. This is not unusual. Because each puzzle really is a dynamic physics simulation rather than a problem with a hard-coded solution, many of them have multiple solutions, some of which may never have been thought of by the designers. In this quality as well The Incredible Machine is, yet once more, similar to Lemmings.

The game includes many more parts than we had available to us in the first puzzle; there are some 45 of them in all, far more than any single puzzle could ever use. Even the physical environment itself eventually becomes a variable, as the later puzzles begin to mess with gravity and atmospheric pressure.

We won’t look at anything that daunting today, but we should have a look at a somewhat more complicated puzzle from a little later in the game, one that will give us more of a hint of the engine’s real potential.

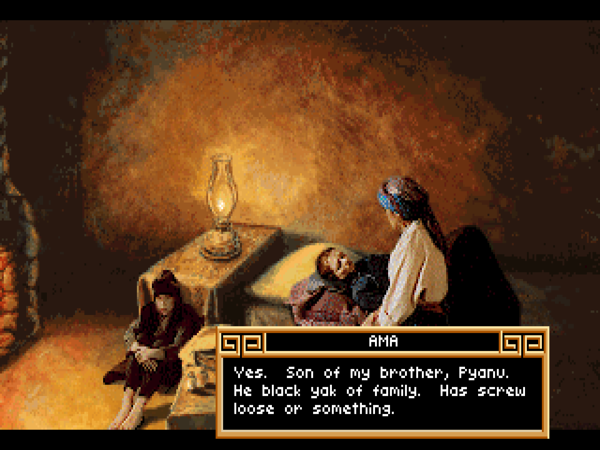

In tribute to Mouse Trap (and because your humble correspondent here just really likes cats), this one will be a literal game of cat and mouse, as shown above. We need to move Mort the Mouse from the top right corner of the screen to the vaguely basket-like enclosure at bottom left, and we’ll have to use Pokey the Cat to accomplish part of that goal. We have more parts to work with this time than will fit in the parts window to the right. (We can scroll through the pages of parts by clicking on the arrows just above.) So, in addition to the two belts, one gear, one electric motor, two electric fans, and one generator shown in the screenshot below, know that we also have three ramp pieces at our disposal.

Already with the starting setup, a baseball flips on a household power outlet, albeit one to which nothing is initially connected.

We can connect one of the fans to the power outlet to blow Mort toward the left. Unfortunately, he gets stuck on the scenery rather than falling all the way down to the next level.

So, we need to alter the mouse’s trajectory by using one of our ramp pieces; note that these, like many parts, can be flipped horizontally and stretched to suit our needs. Our first attempt at placing the ramp does cause Mort to fall down to the next level, and he then starts running away from Pokey toward the right, as we want. But he’s not fast enough to get to the end of the pipe on which he’s running before Pokey catches him. This is good for Pokey, but not so good for us — and, needless to say, least good of all for Mort. (At least the game politely spares us the carnage that ensues after he’s caught by making him simply disappear.)

A little more experimentation and we find a placement of the ramp that works better.

Now we just have to move the mouse back to the left and into the basket. The most logical approach would seem to be to use the second fan to blow him there. Simple enough, right? Getting it running, however, will be a more complicated affair, considering that we don’t have a handy mains-power outlet already provided down here and that our fan’s cord won’t stretch anywhere near as far as we need it to in order to utilize the outlet above. So, we begin by instead plugging our electric motor into the second socket of the outlet we do have, and belting it up to the gear that’s already fixed in place.

So far, so good. Now we mesh the gear from our box of parts to the one that’s already on the board, and belt it up to our generator, which provides us with another handy power outlet right where we need it.

Now we place our second fan just right, and… voila! We’ve solved the puzzle with two ramp pieces to spare.

The experience of working through the stages of a solution, getting a little closer each time, is almost indescribably satisfying for anyone with the slightest hint of a tinkering spirit. The Incredible Machine wasn’t explicitly pitched as an educational product, but, like a lot of Sierra’s releases during this period, it nevertheless had something of an educational — or at least edutational — aura, what with its bright, friendly visual style and nonviolent premise (the occasional devoured mouse excepted!). There’s much to be learned from it — not least that even the most gnarly problems, in a computer game or in real life, can usually be tackled by breaking them down into a series of less daunting sub-problems. Later on, when the puzzles get really complex, one may question where to even start. The answer, of course, is just to put some parts on the board and connect some things together, to start seeing what’s possible and how things react with one another. Rolling up the old sleeves and trying things is better than sitting around paralyzed by a puzzle’s — or by life’s — complexity. For the pure tinkerers among us, meanwhile, the game offers a free-form mode where you can see what sort of outlandish contraption you can come up with, just for the heck of it. It thus manages to succeed as both a goal-oriented game in the mode of Lemmings and as a software toy in the mode of its 1980s inspirations.

As we’ve already seen, Jeff Tunnell Productions had been formed with the intention of making smaller, more formally innovative games than those typically created inside the main offices of Dynamix. It was tacitly understood that games of this stripe carried with them more risk and perhaps less top-end sales potential than the likes of Damon Slye’s big military flight simulators; these drawbacks would be compensated for only by their vastly lower production costs. It’s thus a little ironic to note that The Incredible Machine upon its release on December 1, 1992, became a major, immediate hit by the standard of any budget. Were it not for another of those aforementioned Damon Slye simulations, a big World War II-themed extravaganza called Aces of the Pacific that had been released just days before it, it would actually have become Dynamix’s single best-selling game to date. As it was, Aces of the Pacific sold a few more absolute units, but in terms of profitability there was no comparison; The Incredible Machine had cost peanuts to make by the standards of an industry obsessed with big, multimedia-rich games.

The size comparisons are indeed telling. Aces of the Pacific had shipped on three disks, while Tunnell’s previous project, the interactive cartoon The Adventures of Willy Beamish, had required six. The Incredible Machine, by contrast, fit comfortably on a single humble floppy, a rarity among games from Dynamix’s parent company Sierra especially, from whose boxes sometimes burst forth as many as a dozen disks, who looked forward with desperate urgency to the arrival of CD-ROMs and their 650 MB of storage. The Incredible Machine needed less than 1 MB of space in all, and its cost of production had been almost as out of proportion with the Sierra norm as its byte count. It thus didn’t take Dynamix long to ask Jeff Tunnell Productions to merge back into their main fold. With the profits The Incredible Machine was generating, it would be best to make sure its developers remained in the Dynamix/Sierra club.

There was much to learn from The Incredible Machine‘s success for any student of the evolving games industry who bothered to pay attention. Along with Tetris and Lemmings before it, it provided the perfect template for “casual” gaming, a category the industry hadn’t yet bothered to label. It could be used as a five-minute palate-cleanser between tasks on the office computer as easily as it could become a weekend-filling obsession on the home computer. It was a low-investment game, quick and easy to get into and get out of, its premise and controls obvious from the merest glance at the screen, yet managed to conceal beneath its shallow surface oceans of depth. At the same time, though, that depth was of such a nature that you could set it aside for weeks or months when life got in the way, then pick it up and continue with the next puzzle as if nothing had happened. This sort of thing, much more so than elaborate interactive movies filmed with real actors on real sound stages — or, for that matter, hardcore flight simulators that demanded hours and hours of practice just to rise to the level of competent — would prove to be the real future of digital games as mass-market entertainments. The founding ethos of the short-lived entity known as Jeff Tunnell Productions — to focus on small games that did one thing really, really well — could stand in for that of countless independent game studios working in the mobile and casual spaces today.

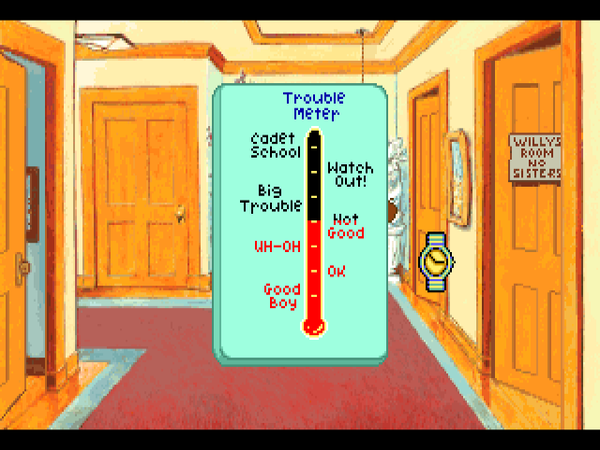

Still, it would be a long time before The Incredible Machine and games like it became more than occasional anomalies in an industry obsessed with cutting-edge technology and size, both in megabytes and in player time commitment. In the meantime, developers who did realize that not every gamer was thirsting to spend dozens of hours immersed in an interactive Star Wars movie or Lord of the Rings novel could do very well for themselves. The Incredible Machine was the sort of game that lent itself to almost infinite sequels once the core engine had been created. With the latter to hand, all that remained for Tunnell and company was to churn out more puzzles. Thus the next several years brought The Even More! Incredible Machine, a re-packaging of the original game with an additional 73 puzzles; Sid & Al’s Incredible Toons, which moved the gameplay into more forthrightly cartoon territory via its titular Tom & Jerry ripoffs; and The Incredible Machine 2 and The Incredible Toon Machine, which were just what they sounded like they would be. Being the very definition of “more of the same,” these aren’t the sort of games that lend themselves to extended criticism, but certainly players who had enjoyed the original game found plenty more to enjoy in the sequels. Along the way, the series proved quietly but significantly influential as more than just one of the pioneers of casual games in the abstract: it became the urtext of the entire genre of so-called “physics simulators.” There’s much of The Incredible Machine‘s influence to be found in more than one facet of such a modern casual mega-hit as the Angry Birds franchise.

For his part, Jeff Tunnell took away from The Incredible Machine‘s success the lesson that his beloved small games were more than commercially viable. He spent most of the balance of the 1990s working similar territory. In the process, he delivered two games that sold even better than The Incredible Machine franchise — in fact, they became the two best-selling games Dynamix would ever release. Trophy Bass and 3-D Ultra Pinball are far from the best-remembered or best-loved Dynamix-related titles among hardcore gamers today, but they sold and sold and sold to an audience that doesn’t tend to read blogs like this one. While neither is a brilliantly innovative design like The Incredible Machine, their huge success hammers home the valuable lesson, still too often forgotten, that many different kinds of people play many different kinds of games for many different reasons, and that none of these people, games, or reasons is a wrong one.

(Sources: Sierra’s InterAction news magazine of Fall 1992 and Winter 1992; Computer Gaming World of March 1992 and April 1993; Commodore Microcomputers of November/December 1986; Matt Barton’s interviews with Jeff Tunnell in Matt Chat 200 and 201; press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play.

All of the Incredible Machine games are available for purchase in one “mega pack” from GOG.com.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | That, anyway, is the story which both Jeff Tunnell and Kevin Ryan tell in interviews today, which also happened to be the only one told in an earlier version of this article. But this blog’s friend Jim Leonard has since pointed out the existence of a rather obscure children’s game from the heyday of computerized erector sets called Creative Contraptions, published by the brief-lived software division of Bantam Books and created by a team of developers who called themselves Looking Glass Software (no relation to the later, much more famous Looking Glass Studios). It’s a machine construction set in its own right, one which is strikingly similar to the game which is the main subject of this article, even including some of the very same component parts, although it is more limited in many ways than Tunnell and Ryan’s creation, with simpler mechanisms to build out of fewer parts and less flexible controls that are forced to rely on keystrokes rather than the much more intuitive affordances of the mouse. One must assume that Tunnell and Ryan either reinvented much of Creative Contraptions or expanded on a brilliant concept beautifully in the course of taking full advantage of the additional hardware at their disposal. If the latter, there’s certainly no shame in that. |

|---|