Having introduced my ideas about what constitutes a ludic narrative in my last post, I’d now like to set that aside for just a little while to consider games in another way.

I define a game as a dynamic system which, in contrast to other art forms (sorry, Roger Ebert) which are “merely” consumed and appreciated, requires active input from one or more players to make it go. I realize that such a definition excludes some things often referred to as games, such as children’s free-form “games” of pure make-believe, and potentially lets in some questionable things, such as some interactive art installations. We’ll just have to use a bit of common sense in applying this definition, and where necessary fall back yet again on good old George Lakoff.

I think we can usefully divide a game into three components. First we have the system itself, the network of rules which govern play and, indeed, which largely mark the game as a game. Next we have what Noah Wardrip-Fruin calls the surface, the player’s method of getting data into and out of the underlying system. Taken at its most superficial, the surface of a given game can often be described in a few words: a poker player uses the playing cards for both input and output, for instance, while a player of a modern computer game likely uses the mouse for input and the monitor screen for output. However, I really mean for the surface component to be taken more holistically, to be used to cover not only the bare technology of interaction but also the character of that interaction and the scope of affordance (in game-designer speak, the “verbs”) that is allowed. This seems only reasonable; a first-person shooter, for example, provides its own very distinct experience at the surface level, one that is in some ways richer and in some ways more limited than, say, a point-and-click graphic adventure game. And finally, we have the fictional context of the game, the imaginary event being simulated. (Many games are, of course, based on real-life events, but even these must play out anew in the players’ imaginations.) It’s this aspect of games that is one of the keys to my idea of ludic narrative.

The first thing to note about fictional context is that its relative importance to the experience of a game can vary tremendously. In some cases context may not be present at all. Poker and most other traditional card games, for instance, exist purely as abstract systems to be manipulated. Many other games do provide some sort of context, but said context has little relation with the system of rules, being (to use some board-gamer parlance) essentially “painted on” and quickly forgotten during actual play. The board game Monopoly is a classic example of this phenomenon that virtually everyone knows. My wife and I actually play quite a lot of board games, including many examples of so-called “Euro-games” whose elaborate themes and colorful artwork almost always have nothing whatsoever to do with the actual experience of play. I don’t mean this as a criticism; I think I could play Dominion every day for the rest of my life and not tire of it. In this blog, though, I’m obviously most interested in games that have a context that is very important to the player’s experience.

We can legitimately call all such games simulations, in that their rules systems simulate events occurring in a fictional place that exists only in the imagination of the players. They can perhaps trace their oldest progenitor to ancient China, where Sun Tzu, the author of The Art of War, developed a game which simulated the maneuvering of armies in order to help his students learn strategy. It is possible that this game, which Sun Tzu named Wei-Hai, evolved into the abstract strategy game Go over the centuries. Similarly, the modern game of chess, which bears only the merest vestiges of a context in the iconography of its pieces, may have evolved from some other game meant to at least semi-realistically simulate real military strategy.

That and a handful of other historical possibilities aside, the origin of the simulation game as we know it today can really be traced to approximately 1800, when a Prussian writer named Georg Viturinus developed a game he called simply neues Kriegsspiel (“new wargame”). Played on a board of 3600 squares and with some 60 pages of rules, Viturinus’s Kriegsspiel was probably the most complex game ever developed up to that point. Unlike earlier games which dealt with military strategy in the abstract only, Kriegsspiel was relentlessly specific; its game board, for instance, consisted of an accurate map of the Franco-Prussian border, while it endeavored to accurately portray the strengths and weaknesses of the various French and Prussian army units which served as the players’ “pieces.” By 1812 a military officer named Georg Leopold von Reiswitz had refined the game and begun demonstrating it to other officers, hoping to get it adopted as a standard tool for training and strategic and tactical planning. By 1824 a standard set of rules written by von Reiswitz and his son had indeed been adopted, and presumably contributed to the Prussian military’s genius for making war with cold, surgical efficiency. And by 1875, wargames had become standard tools of militaries around the world.

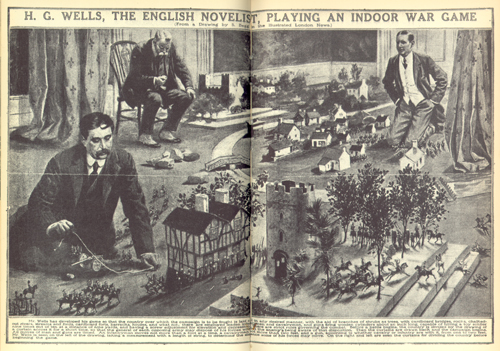

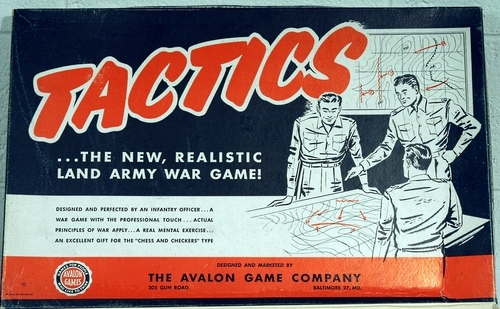

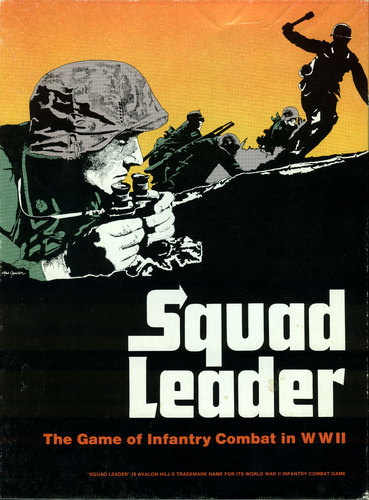

If these games had a very serious — indeed, a deadly — purpose, they were also to certain kinds of minds immensely appealing as intricate systems to be tinkered with, as engines of imagination. Some thus took up wargaming as a hobby, developing elaborate systems of rules which they often played out using carefully carved and painted miniatures representing armies or ships. H.G. Wells was so fascinated with the burgeoning hobby that he published his own set of house rules as the book Little Wars in 1913. Still, the golden age of wargaming began in earnest only in 1954, when Charles S. Roberts founded Avalon Hill to publish the game he had developed, Tactics, the first widely available wargame sold as a set of rules, boards, and pieces ready to play right out of the box. From that beginning sprang a hobbyist network that grew to considerable size, peaking right around the time that the TRS-80 and its rivals from Apple and Commodore were introduced. In fact, 1977 was the year that Avalon Hill released Squad Leader, the most successful wargame of all time with more than 200,000 copies sold. Alas, the trend for non-electronic war games from that point on was a fairly steadily downward one… but that’s a story for another time.

As befits their origin and their label, most of these games dealt with armed conflict of one stripe or another, simulating battles from Marathon to the Golan Heights, and wars from the Trojan War to (a hypothetical) World War III. Some, however, simulated other fields of endeavor, from business to politics to sports. Still others acted as simulations of events which had no real-world antecedents at all, portraying battles in space between alien empires or fantasy conflicts in which mages provided artillery fire and dragons gave air support.

In a wargame, the system of rules is absolutely subservient to the context; indeed, virtually all of the rules derive directly from the context. This is a fascinating and hugely important shift. Think of the rules of chess, so perfectly honed, so balanced and elegant that artists and scientists alike have found them almost irresistably alluring for centuries. Now consider the rules of a complex wargame like Squad Leader, a web of data charts and matrices, of fiddly rules with pages full of exceptions and special cases. Further, in the name of faithfulness to history most sessions of Squad Leader must begin with the deck literally stacked in favor of one side or the other, in terms of numbers, quality of men and material, positioning, etc. Taken as a game qua game, it’s absolutely terrible. Why would anyone want to bother with this mess in lieu of the classical elegance of chess? The answer to that question involves nothing less than a shift in the very nature and purpose of a game.

When we think of playing a game, we still even today envision by default an intellectual and/or physical struggle against one or more opponents, with the goal being to secure victory and glory for ourselves. How remarkable to consider, then, that at the height of wargaming’s glory days prolific designer James F. Dunnigan found in a survey of players that the majority played most of the time solo, moving each side in turn. He provides some reasons for this in The Complete Wargames Handbook:

The most common reasons for playing solitaire are lack of an opponent or preference to play without an opponent, so that the player may exercise his own ideas about how either side in the game should be played without interference from another player. Wargames are, to a very large extent, a means of conducting historical experiments.

The attraction of a wargame is not, as with the context-less chess, found in the system itself, nor even in the proverbial thrill of victory and agony of defeat. They are rather attractive as engines for imagination, and for the reenactment and manipulation of history. Their appeal, in other words, is rooted entirely in their context; divorced from that context, the rules of Squad Leader would be of interest only as a candidate for Worst Game Design Ever. But with it, they are, at least to a certain kind of person, a gateway to history full of infinite possibility and fascination. Wargames are the first experiential games, the first to be ultimately all about the experience of their context. We play and appreciate chess strictly as an abstract system. We do not imagine a knight slaying a pawn; drama derives from the contest of intellect and will we are engaged in with the very real opponent seated across the table. Wargamers, however, use them as a window to another realm; they see the battle playing out in their mind’s eye, and the most imaginative of them even smell the blood and cordite in the air. A popular pastime of wargamers since the dawn of the hobby has been the creation of after-action reports describing particularly exciting sessions. Some of these go far beyond mere notes of moves and countermoves to get quite elaborate indeed, chock full of unusual characters and colorfully described action.

So, are wargames narrative experiences? Well, and while trying not to fall afoul of the painfully tedious academic debate between ludologists and narratologists, it’s hard for me to consider them anything else. Certainly history, at least as it’s generally presented in popular literature, is essentially a narrative. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that in the two non-English languages I somewhat know, German and Danish, the word for history is the same as the word for story. That said, wargames obviously don’t qualify as ludic narratives as I’ve chosen to define that term, for their players manipulate their worlds from on-high, like gods looking down into their simulated worlds, rather than actually entering said worlds to play a role there. As one might expect given their origins and their style of play, they are more akin to interactive historical texts than interactive novels. While they are engines of narrative, they aren’t narratives in themselves; more on this distinction later.

I’m (slowly) getting to the point where experiential games spawned ludic narrative, but first there’s one more historical thread I have to run down. I’ll do that next time.

Jonno

July 23, 2011 at 2:59 am

Speaking of playing wargames solo, I don’t know what kind of nerd^2 this makes me, but between the ages of 12-16 I spent most of my pocket money buying RPG rule books & modules (D&D, Traveller, Runequest, GURPS, and a heap more I forget) which I never played with anyone, nor even wanted to play with anyone – I was just fascinated by the way that a complex system could be documented and (given enough study) understood.

As I write this, I realise it is probably the same instinct that has me scouring Ebay for deep technical references on obsolete computers (canonical examples being “Mapping the C64” and “Beneath Apple DOS”).

And indeed, it is the same instinct that has me reading this website :-)

matt w

July 26, 2011 at 3:20 am

myes. Me too. And I think we shouldn’t underestimate the “lack of an opponent” factor — what are the odds that you’d know someone who would take the time to learn the fat old rulebook of more than one of your games? And then how often would you find the time to get together and play them, and what were the chances that your board setup would make it to your next session without getting wiped out by the cat? So many of these games started with a half hour of stacking little bits of cardboard.

Sig

July 25, 2011 at 9:40 pm

I hesitate to guess how many RPG books I’ve bought which will never be used in play with another person.

JuntMonkey

December 5, 2012 at 10:48 pm

Your description of people filling in details with their imaginations and writing “after-action reports” strongly resembles the seasons I play in NBA Live games and my current efforts to write down the histories. Pretty much the exact same thing, just on a basketball court instead of a battlefield.

Scott M. Bruner

April 29, 2015 at 7:36 pm

This post really hit the mark with me.

Before I lost all my time to the necessities of life and work, I played Strat-O-Matic baseball and Action! PC football in exactly the same manner as these wargames – solo and not to determine who I could “beat” but as historical simulations and recreations.

In addition to the “What If?” scenarios you posit that wargamers do, I would also add that solo play of “experiential” games provides an interactive method of relating to history. The wargame gets to understand Patton’s challenges more clearly, the sports recreater (me) gets to know more about classic ballplayers – and the context they played in.

Maybe you mention this later? (I’m just catching up on some old entries I evidently missed the first time around.)

Jimmy Maher

April 30, 2015 at 7:47 am

I have an uncle who still plays tabletop war games, 90 percent of the time solo, in exactly this way. He says it gives him a much greater appreciation of military history than he could ever get from books or maps or battlefield visits (all of which he’s also done plenty of).

I haven’t touched on this so much in that I haven’t given any real space to military or sports simulations or war games so far. However, that could very well be changing soon.

Phil Strahl

February 20, 2017 at 12:57 am

Hi Jimmy, I’m reading up on all your Blog posts (as enlighting as entertaining!) and being a German native speaker, I couldn’t help but notice how you spelled “Kriegsspiel” in this article. You got it right the 3rd time, but the first two times you swapped the letters ‘e’ and ‘i’ in “…spiel” :)

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2017 at 9:59 am

My German wife would be ashamed. Thanks!

Mike Taylor

October 12, 2017 at 10:22 pm

Typo: “A popular past-time of wargamers”. Should be “pastime”.

Jimmy Maher

October 13, 2017 at 5:30 am

Thanks!

Jacob Bauer

November 2, 2017 at 1:37 pm

“its relative important to the experience” → “its relative importance to the experience”

“By 1812 a military office named” → “By 1812 a military officer named”

Jimmy Maher

November 3, 2017 at 8:05 am

Thanks!

Matt Ludwig

May 10, 2018 at 11:54 pm

Interestingly, “history” and “story” were both borrowed from the same Old French word (“estoire”) within a century or two, and were completely synonymous for a couple centuries.

Jimmy Maher

May 11, 2018 at 5:12 am

In Danish (and presumably other Scandinavian languages), this is still the case. “Historie” can mean “history” or simply “story,” depending on the context. The same is true in the case of the German “Geschichte.”

Jeff Nyman

May 1, 2019 at 4:31 pm

“That said, wargames obviously don’t qualify as ludic narratives as I’ve chosen to define that term, for their players manipulate their worlds from on-high, like gods looking down into their simulated worlds, rather than actually entering said worlds to play a role there.”

I’m not sure I would agree with this part. I agree that it might not fit your definition of ludic narrative … but only if you assume players weren’t, as you say, “entering said worlds to play a role there.”

But many such players were doing just that. Yes, you may be ultimately controlling armies. But at any given point you could imagine yourself stepping into the shoes of a tank crew. Or a pilot. Or an infrantryman. You were actually exploring many viewpoints that were taking place in the same context, which could also make you think more about the story.

A pilot who drops bombs and doesn’t see up close the results is different from the infantryman who is part of a squad supporting a tank column, for example. The general who, quite literally, can move people around on a board doesn’t have the same empathy as the sergeant who has to actually order people to carry out the general’s wishes. The generals also often have a more full picture than the grunts on the ground do.

So my only point here is that you can actually really exercise your imagination by jumping between these polarities of thought. That’s something you can’t do as easily if you are simply taking on one role (in one persona) for the duration of a game.

Phillip H

March 12, 2024 at 5:37 am

It tends to be more frustrating to discover by exploring a natural-language system that doing thing X is not allowed, than to see up front that it’s not on a menu of explicitly stated options.

That difference between genres becomes less as both move toward the same “point and click” kind of interface.

There’s been to a lesser extent a similar trend in paper and pencil games. The original D&D left a lot up to the referee’s adjudication, presenting little in the way of hard rules.

More recently, the trend has been toward siloing options so that an economy of ‘purchasing’ entitlements for a figure to perform certain actions is a more important sub-game.

There’s also a ‘narrativist’ school in which the mechanical formalism is less about determining what happens than about determining who has authorial permission to describe the outcome of an event. That flexibility is not so easily applied to an artificial ‘intelligence’.

There was a pronounced “uncanny valley” in CRPGs in the 1990s, with detailed visual rendering of discrete objects out of sync with expectations of the environment actually working in the terms that implied.

It seems that the issues involved have broadly been sorted out into a new set of widely accepted conventions as to how much symbolism (as opposed to literalism) is appropriate.

Graeme Cree

March 31, 2025 at 3:23 pm

“…the rules of Squad Leader would be of interest only as a candidate for Worst Game Design Ever”

Well, Squad Leader was quickly superseded by Advanced Squad Leader, a much better written set of rules for basically the same game system. The original Dungeons & Dragons rules were almost unplayable before being replaced by Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.

There was an SPI game called The Fall of Rome that legend had it was the worst written game of all time. I never played it, but I think “The Complete Book of Wargames” called it wargaming’s version of the 1962 Mets.