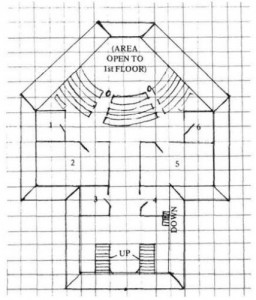

There’s a whole lot of Dungeons and Dragons in the original Adventure. Its environs may be based on Kentucky’s Colossal Cave, but the central premise of exploring and looting an underground environment filled with strange dangers and treasure has as much to do with D&D as it does with caving. Even some of the ways in which that environment is presented are strikingly similar. A typical D&D dungeon was, like Adventure‘s, divided into a series of discrete, self-contained rooms. Here’s one of the maps that accompany Temple of the Frog, the first published D&D “adventure module,” which appeared as part of the second D&D supplement, Blackmoor, in 1975:

And here’s the description of a couple of these numbered rooms:

Room 3: Is the headquarters of the traders sent out to sell the junk and is also the office of the chief of accounting. Hidden in this desk are 600 pieces of platinum that he has embezzled. (The High Priest knows about this but does not seem to care.)

Room 4: Is the office of the Commander of the palace guard where he goes to run the security arrangements in the Temple. Within are the master alarms for the palace, so that the exact location of trouble can be registered and personnel sent to counter the intrusion. From here he can communicate, via a desk communicator, with other officers and sergeants under his command. There is always an officer and two sergeants on duty in this room and only the rings worn by the High Priest Commander of the Guard or the Chief Keeper will gain admittance. (No one is aware that the latter has such a privilege, and it has not been used for many years.)

Later D&D adventures made this similarity with the IF room even more obvious by including a boxed text with every room that the DM should read to the players upon their first entering, just like the ubiquitous IF room description. At least under all but a very skilled DM, the rooms of a D&D dungeon tended to feel oddly separate from one another, each its own little self-contained universe just like in a text adventure; many was the party that fought a pitched battle with a group of monsters, then, upon finally vanquishing them, stumbled upon some more still slumbering peacefully in the next room just as the room description said they should be, undisturbed by the carnage that just took place next door. Speaking of combat, the heart of most D&D adventures, Adventure even had a modicum of that as well, in the form of the annoying little dwarfs that harried the player until they were all dispatched.

For all these similarities and for all the acknowledged influence that his experiences as a D&D player had on Crowther’s original work, though, virtually no one refers to Adventure or its many antecedents as computer RPGs. What gives? One thing we might take note of is that Crowther made no real attempt to translate the actual D&D rules into his computer game. He took inspiration from some of its themes and ideas, but then went his own way, whereas the mechanical debt that the family of games I now want to begin to cover owed to D&D was as important as the thematic debt. Just leaving it at that seems a bit unsatisfying, though. Maybe we can do a little bit better, and in the process come up with something that might be useful in a broader context.

Matt Barton says something really interesting in the first chapter of Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games:

To paint with a broad brush, we could say that the adventure gamer prioritizes deductive and qualitative thinking, whereas the CRPG fan values more inductive and quantitative reason. The adventure gamer works with definitions and syllogisms; the CRPG fan reckons with formulas and statistics. The only way for a character in a CRPG to advance is by careful inductive reasoning: if a certain strategy results in victory in six out of ten battles, it is better than another strategy that yields only three out of ten victories. This type of inductive reasoning is rare in adventure games but is plentiful in CRPGs, where almost every item has some statistical value (e.g., a longsword may do ten percent less damage than a two-handed sword, but allows the use of a shield).

These differences in thinking arise of course from very different approaches to game design and narrative on the part of the works’ creators. The typical adventure-game designer spends most of her time crafting a pre-defined experience for the player, building in a series of generally single-solution set-piece puzzles and a single (or, at most, modestly branching) narrative arc. The CRPG designer, meanwhile, pays less attention to such particulars in favor of crafting an intricate system of rules and interactions, from which the experience of play, even much of the narrative, will emerge. CRPGs, in other words, are essentially simulation games, albeit what is being simulated is an entirely fictional world.

At first blush, there perhaps doesn’t seem to be any room for debate about which approach is “better.” After all, if given a choice between jumping through hoops to progress down a single rigid path or crafting one’s own experience, writing one’s own story in the course of play, who would choose the former? In actuality, though, things aren’t so clear-cut. There are inevitable limits to any attempt to create lived experience through a computer simulation. It’s perfectly feasible to simulate a group of adventurers descending into a dungeon and engaging in combat with the monsters they find there; it’s not so easy to simulate, say, the interpersonal dynamics of a single unexceptional family. People have tried and continue to try, but so far the simulational approach to ludic narrative has dramatically limited the kinds of stories that can be interactively lived. Thus, the simulational approach can paradoxically be as straitening as it is freeing. And there’s another thing to consider. The more we foreground the simulational, the more we emphasize player freedom as our overriding goal, the further we move from the old ideal of the artist who shares his vision with the world. What we create instead may certainly be interesting, even fascinating, but whatever it ends up being it becomes more and more difficult for me to think of it as art. Which is not to say that every game design should or must aspire to be art, of course; given my general experience with games that explicitly make claims to that status, in fact, I’d just as soon have game designers just concentrate on their craft and let the rest of us make such judgments for ourselves.

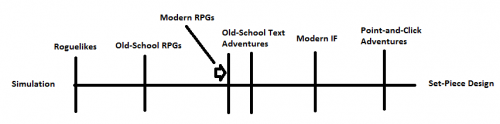

I must be sure to point out here that “emergence” and “set-piece design” do not form distinct categories of games, but rather the opposite poles of a continuum. Virtually every game has elements of both; consider the scripted dialog that appears onscreen just before the player kills the Big Foozle in a classic CRPG, or the item that a player must have in her inventory to solve the otherwise set-piece text-adventure puzzle. It’s also true that disparate games even within the same genre place their emphasis differently, and that over time trends have pulled entire genres in one direction or another. Here’s a little diagram I put together showing some of what I mean:

As the diagram shows, modern big-budget RPGs such as those from Bioware have actually tended to include much more set-piece story than their classic predecessors, in spite of the vastly more computing power they have to devote to pure simulation. (There’s some great material in Noah Wardrip-Fruin’s Expressive Processing about the odd dichotomy between the amazingly sophisticated simulational part of a game like Knights of the Old Republic and the limited multiple-choice conversation system the player is forced into whenever emphasis shifts from the hard mechanics of exploration and combat to the soft vagaries of story and interpersonal relationships.) Modern IF has also trended away from simulation, de-emphasizing the problems of geography, light sources, inventory management, sometimes even combat of old-school text adventures to deliver a more author-crafted, “literary” experience.

But I wanted to define the CRPG, didn’t I? Okay, here goes:

A computer role-playing game (CRPG) is an approach to ludic narrative that emphasizes computational simulation of the storyworld over set-piece, “canned” design and narrative elements. The CRPG generally offers the player a much wider field of choice than other approaches, albeit often at the cost of narrative depth and the scope of narrative possibility it affords to the designer.

At least for now, I think I’m going to leave it at that. Most other definitions tend to emphasize character-building and leveling elements as a prerequisite, but, while I certainly acknowledge their presence in the vast majority of CRPGs, it seems limiting to the form’s possibilities to make that a requirement. Of course, I could have also simply used the definition we used in the 1980s: in adventure games you explore and solve puzzles, in CRPGs you explore and kill monsters. But that’s just too easy, isn’t it?

So, we hopefully now have some idea of what it really is that separates a CRPG from the works of Crowther and Woods and Adams. With that in place, we can begin to look at the first examples of the form next time.

Felix Pleșoianu

August 15, 2011 at 6:45 am

I’ll argue that simulation requires *fewer* computing resources than canned storytelling, as evidenced by games such as The Oregon Trail or, well, pretty much anything in Ahl’s Basic Computer Games. In fact, I’ve been surprised to see how many of these simulation games can be implemented in a language as restrictive as Tiny BASIC. Whereas even a Scott Adams text adventure requires some room to store messages, and some string processing to put together responses.

That said, your diagram’s neat. I never thought of it this way.

Jimmy Maher

August 15, 2011 at 9:31 am

I’d say that it really depends on what kind of “computing resources” we’re discussing. The deeper the simulation, the more and more elaborate code must be run, of course, which is going to require more CPU power. On the other hand, a largely set-piece design might require more memory to store all of that text and story, while its very simplistic simulation layer is rather trivial. (See most modern point-and-click graphic adventures, which often offer little more real interactivity than a hypertext.)

Of course, in Bioware RPGs and other big modern games the vast majority of all computing resources — CPU, memory, hard drive, etc. — goes to multimedia assets, graphics, sound, music. The resources consumed by everything else are trivial in comparison.

Jason Scott

August 16, 2011 at 6:19 am

Since this is about the only weblog/site doing anything in-depth along these lines, allow me to fill in some information and take a mea culpa.

Without a doubt, Will Crowther plays a few games of D&D with some BBN folks. I contacted the DM for those games about being interviewed when I was first reaching out for potential subjects and he thought I was beyond nuts. Rightly so, but as the rest of the movie hopefully shows, I was consistently nuts. As “Willie the Thief”, Crowther definitely had tried the system out prior to when he worked on Adventure. As an additional factor, Will and Pat Crowther had spent time on a computerized map system for the Cave Research Foundation, which they spent an awful amount of time on, and which was told me informally as being one that ultimately needed enough revision to be not useful after a certain point. (Then again, the CRF is constantly re-mapping and double-checking work to ensure both a correct mapping and to accommodate fall-ins, newly discovered passages, and so on.)

So, after Will Crowther (through proxies) showed no interest in being part of this film, I decided he needed to be mentioned but not dwelled upon and I did way too good a job.

As a result, the full breadth of Crowther got really short-changed, and it was mostly to respect his wishes, when I should have gone further into it. I suspect a slight version 1.2 of GET LAMP will come out at some point, and that remixed HD version would almost definitely have this point dragged back into it, where it belongs.

So yes, D&D does come into it, and while even recent reviews or histories mention Woods bringing in all the fantasy and treasures, Crowther absolutely had them before, with Woods adding material to them. Dennis Jerz did amazing work on this.

Jimmy Maher

August 16, 2011 at 1:53 pm

For what it’s worth, in watching the film I never remotely felt like Crowther was being snubbed. I suspect that Crowther remembers Adventure merely as something he idly hacked on for a few months before moving on to something more interesting, and cannot understand why all of us younger nerds are always *bothering* him about it. I know that he did correspond at least a little bit with Dennis Jerz, which should count as something of a coup for a project that was full of them.

Michael Davis

December 8, 2014 at 4:07 pm

(The High Priest knows about this but does not see to care.)

Room 4: Is the office of the Commander of the place guard

Is that “seem to care” and “palace guard”?

Jimmy Maher

December 9, 2014 at 12:22 am

Yes, it is. Fixed. Thanks!

Michael

May 14, 2019 at 9:03 pm

It’s a lot of years later to catch a typo, but did you mean “actuality” instead of “actually” here:

* “In actually, though, things aren’t so clear-cut.”

Jimmy Maher

May 15, 2019 at 3:15 pm

Thanks!

Will Moczarski

June 13, 2019 at 3:35 am

from he works -> from the works

Although I understand that you wanted to limit your comparison to two genres, many modern FPS games would be very much on the set-piece design end of your scale because they started to implement elements of adventure games very early on (I‘d say that LucasArts’ Dark Forces is likely to be the first example). My point is that it can be used quite well to understand and describe genre hybridization in general – and seeing that most CRPGs, adventure games (and I would add: action adventures) share the same roots, the type of game emphasizing exploration above most other things possibly started out as a hybrid. Puzzles and combat are both mostly used as obstacles to slow down or halt exploration, after all. Open-world games and MMORPGs are even more concerned with the aspect of the simulation of a gameworld, accordingly.

Jimmy Maher

June 13, 2019 at 6:44 am

Thanks!

Fronzel

February 23, 2021 at 7:03 pm

“…only the rings worn by the High Priest Command of the Guard or…”

I think this is a typo or maybe two. Is it supposed to be “High Priest’s Commander of the Guard”?

Jimmy Maher

February 25, 2021 at 7:34 am

Thanks!

Chris Billows

September 5, 2021 at 1:36 pm

Your Simulation to Set-Piece diagram is excellent. It illustrates exactly the type of thinking I’ve adopted when it comes to categorizing video games. I now see groups of axis/continuums of play ingredients that are mixed together to create the video game we experience.

While your axis is high concept, we can use that model to help drill down into the layers of play that makes up a video game. How many doses of simulation style play are we adding to this layer of the game? Are we mixing in some set-piece or other ingredients? I like the concept of ingredients because it feels like a chemical process that is both precise and yet mysterious.

The book Expressive Processing’s link is now at https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/expressive-processing

Jeff Nyman

October 15, 2021 at 7:37 pm

I feel Chris’s point about the “ingredients” is a really good one.

For example, if we take that point, I think it would help frame this article a bit to realize that simulation is basically an attempt to encode real-world or hypothetical-world processes over time. Any simulation will require a model, with the model being used to represent certain aspects or characteristics of the process(es). The “simulation” part is then literally allowing that model to evolve over time via interactions with it, which is usually mediated by some system of rules.

For example, I can have a simulational context (say of a day-night world with moving fauna) and yet still have a series of set-piece interactions that tell a story in that world. Perhaps those set-pieces, in fact, have elements that rely on the day-night cycle. Thus you could argue the simulational aspect is very much foregrounded but would not necessarily move away from the idea of art or the ability to have a narrative.

The idea of text adventures that utilize inventory management or perishable light sources is also something that exists in some CRPGs. But let’s consider this in a different context. Let’s contrast, say, “Call of Duty” versus “Arma.” In the former, you can obviously take numerous bullet hits that would incapacitate, if not kill, you in real life. And healing is just a matter of getting that “health pack” (applying it as you’re dodging shrapnel, of course).

Still, though, there might be many aspects of the simulational: how tanks actually move; how enemy soldiers respond in combat, etc. What we currently mislabel “artificial intelligence” in games is more often really just simulation based on models. (Which is why it often goes so wrong in some games. Either the models are faulty, or too complex to evolve reliably, or don’t interface well with the system of rules.)

Now “Arma”, on the other hand, can be very realistic. One shot that would be fatal in real life is fatal in the game. You can have it such that shots to your leg or arm, while not fatal, do incapacitate you in terms of what you can carry, how you can shoot, or how well you can move. That game, too, has a lot of simulational aspects; certainly more than “Call of Duty.” Yet both do also feature set-piece scenarios in terms of events that happen as part of the overall narrative of their conflicts.

McTrinsic

July 29, 2022 at 11:59 am

Being aware thatcher have thread necrophilia here, I feel compelled to comment.

This year, I have played the second in the series of (c.-) role-playing games based on the Pathfinder IP which in turn is based upon a later version of Dungeons and Dragons.

Specifically, I am referring to the game „Wrath of the Righteous“.

My impression is that it totally blows away your distinguished consideration between adventure / ludic narrative and rpgs. Incredible story and impressive characters that join you during this adventure make it a notable overall experience. I’d put it on par with Ultima IV and Pool of Radiance.

Not because of the technology used, such as graphics or sound of effects or what have you. But because of your interaction with the fictional world. I have never seen a game where

people fancy so many replays because of different aspects of the story.

I’d describe it like this: where in a classical IF or adventure you enter commands into a parser, in WotR you engage in fights according to a crpg ruleset to drive the story forward.

Considering this, it leaves me to wonder where the future will take us with new possibilities.

Exciting times ahead!

Phillip H

March 12, 2024 at 4:35 am

In my experience, IF usually calls for more (not less) modeling of the world, because what the player can do in it is less arbitrarily limited than usual in a CRPG.

The main genre distinction, I think, is that the latter makes more of the numbers player facing. Most people furthermore want “leveling up” the stats to be a central element of play.

An adventure game puts more importance on role-playing in the sense of the player’s choices of behavior; a CRPG emphasizes the quantitative modeling the character.

Neither of these is intrinsically tied to a more open or more linear scenario structure.

Of course it’s easier to make a sprawling randomly generated ‘world’ when that has less depth. It’s also easier to implement combat as a series of dice tosses than to implement situations with more sophisticated permutations. Above all, it’s easier to populate the milieu with bags of hit points than with characters displaying personality.

The difficulty ramps up when, in place of a human game master able to improvise, you have a computer incapable of handling anything for which a rule has not been stipulated.

SpookyFM

June 5, 2025 at 7:19 am

I’ll have to do what all research psychologists worth their salt have to do: As soon as someone postulates a bipolar continuum, we are obliged to respond: “No, _actually_ those are two orthogonal dimensions!”

I haven’t read all your posts in order so maybe you have touched on this in later posts but, as the last few posts have touched upon, I believe that simulation and narrative set-piece design are not necessarily mutually exclusive. However, to combine the two (i.e. to reach a point on the two-dimensional plane that is high on both) _and_ is fun to play, is very hard and a _lot_ of work. But I can imagine a game (and there are some) where the decision which parts of the fixed narrative the player gets to experience is decided upon by complex systems.

Inkle’s 80 Days is a good example, I think, because the plot can vary wildly, not only because of where you go or what you have with you but also because of some stats the game keeps, some explicitly, some implicitly. It’s certainly not at the very top of the upper-right quadrant of my imagined coordinate system, but it certainly has both simulative as well as design elements.