One could make a strong argument for the manned Moon landing and the Internet as the two greatest technological achievements of the second half of the twentieth century. Remarkably, the roots of both reach back to the same event — in fact, to the very same American government agency, hastily created in response to that event.

At dawn on October 5, 1957, a rocket blasted off from southern Kazakhstan. Just under half an hour later, at an altitude of about 140 miles, it detached its payload: a silver sphere the size of a soccer ball, from which four antennas extended in vaguely insectoid fashion. Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite, began to send out a regular beep soon thereafter.

It became the beep heard round the world, exciting a consternation in the West such as hadn’t been in evidence since the first Soviet test of an atomic bomb eight years earlier. In many ways, this panic was even worse than that one. The nuclear test of 1949 had served notice that the Soviet Union had just about caught up with the West, prompting a redoubled effort on the part of the United States to develop the hydrogen bomb, the last word in apocalyptic weaponry. This effort had succeeded in 1952, restoring a measure of peace of mind. But now, with Sputnik, the Soviet Union had done more than catch up to the Western state of the art; it had surpassed it. The implications were dire. Amateur radio enthusiasts listened with morbid fascination to the telltale beep passing overhead, while newspaper columnists imagined the Soviets colonizing space in the name of communism and dropping bombs from there on the heads of those terrestrial nations who refused to submit to tyranny.

The Soviets themselves proved adept at playing to such fears. Just one month after Sputnik 1, they launched Sputnik 2. This satellite had a living passenger: a bewildered mongrel dog named Laika who had been scooped off the streets of Moscow. We now know that the poor creature was boiled alive in her tin can by the unshielded heat of the Sun within a few hours of reaching orbit, but it was reported to the world at the time that she lived fully six days in space before being euthanized by lethal injection. Clearly the Soviets’ plans for space involved more than beeping soccer balls.

These events prompted a predictable scramble inside the American government, a circular firing squad of politicians, bureaucrats, and military brass casting aspersions upon one another as everyone tried to figure out how the United States could have been upstaged so badly. President Dwight D. Eisenhower delivered a major address just four days after Laika had become the first living Earthling to reach space (and to die there). He would remedy the crisis of confidence in American science and technology, he said, by forming a new agency that would report directly to the Secretary of Defense. It would be called the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA. Naturally, its foremost responsibility would be the space race against the Soviets.

But this mission statement for ARPA didn’t last very long. Many believed that to treat the space race as a purely military endeavor would be unwise; far better to present it to the world as a peaceful, almost utopian initiative, driven by pure science and the eternal human urge to explore. These cooler heads eventually prevailed, and as a result almost the entirety of ARPA’s initial raison d’être was taken away from it in the weeks after its formal creation in February of 1958. A brand new, civilian space agency called the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was formed to carry out the utopian mission of space exploration — albeit more quickly than the Soviets, if you please. ARPA was suddenly an agency without any obvious reason to exist. But the bills to create it had all been signed and office space in the Pentagon allocated, and so it was allowed to shamble on toward destinations that were uncertain at best. It became just another acronym floating about in the alphabet soup of government bureaucracy.

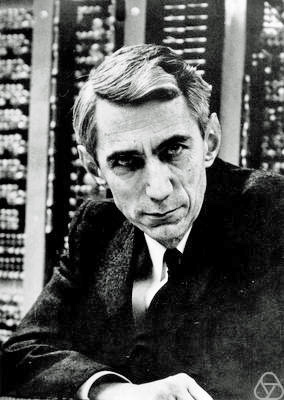

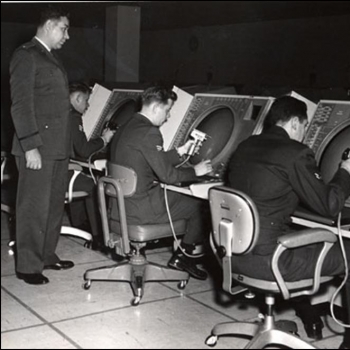

Big government having an inertia all its own, it remained that way for quite some time. While NASA captured headlines with the recruitment of its first seven human astronauts and the inauguration of a Project Mercury to put one of them into space, ARPA, the agency originally slated to have all that glory, toiled away in obscurity with esoteric projects that attracted little attention outside the Pentagon. ARPA had nothing whatsoever to do with computing until mid-1961. At that point — as the nation was smarting over the Soviets stealing its thunder once again, this time by putting a man into space before NASA could — ARPA was given four huge IBM mainframes, leftovers from the SAGE project which nobody knew what to do with, for their hardware design had been tailored for the needs of SAGE alone. The head of ARPA then was a man named Jack Ruina, who just happened to be an electrical engineer, and one who was at least somewhat familiar with the latest developments in computing. Rather than looking a gift horse — or a white elephant — in the mouth, he decided to take his inherited computers as a sign that this was a field where ARPA could do some good. He asked for and was given $10 million per year to study computer-assisted command-and-control systems — basically, for a continuation of the sort of work that the SAGE project had begun. Then he started looking around for someone to run the new sub-agency. He found the man he felt to be the ideal candidate in one J.C.R. Licklider.

Lick was probably the most gifted intuitive genius I have ever known. When I would finally come to Lick with the proof of some mathematical relation, I’d discover that he already knew it. He hadn’t worked it out in detail. He just… knew it. He could somehow envision the way information flowed, and see relations that people who just manipulated the mathematical symbols could not see. It was so astounding that he became a figure of mystery to the rest of us. How the hell does Lick do it? How does he see these things? Talking with Lick about a problem amplified my own intelligence about 30 IQ points.

— William J. McGill, colleague of J.C.R. Licklider at MIT

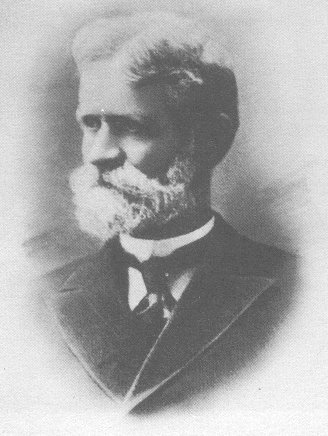

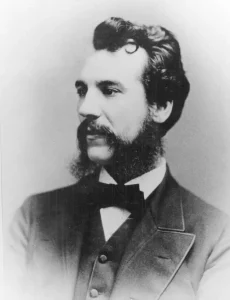

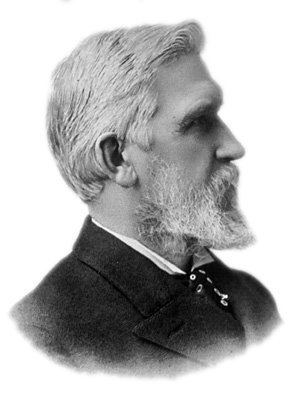

Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider is one of history’s greatest rarities, a man who changed the world without ever making any enemies. Almost to a person, no one who worked with him had or has a bad word to say about him — not even those who stridently disagreed with him about the approach to computing which his very name came to signify. They prefer to wax rhapsodic about his incisive intellect, his endless good humor, his incomparable ability to inspire and motivate, and perhaps most of all his down-to-earth human kindness — not exactly the quality for which computer brainiacs are most known. He was the kind of guy who, when he’d visit the office soda machine, would always come back with enough Cokes for everyone. When he’d go to sharpen a pencil, he’d ask if anyone else needed theirs sharpened as well. “He could strike up a conversation with anybody,” remembered a woman named Louise Carpenter Thomas who worked with him early in his career. “Waitresses, bellhops, janitors, gardeners… it was a facility I marveled at.”

“I can’t figure it out,” she once told a friend. “He’s too… nice.” She soon decided he wasn’t too good to be true after all; she became his wife.

“Lick,” as he was universally known, wasn’t a hacker in the conventional sense. He was rather the epitome of a big-picture guy. Uninterested in the details of administration of the agencies he ostensibly led and not much more interested in those of programming or engineering at the nitty-gritty level, he excelled at creating an atmosphere that allowed other people to become their best selves and then setting a direction they could all pull toward. One might be tempted to call him a prototype of the modern Silicon Valley “disruptor,” except that he lacked the toxic narcissism of that breed of Steve Jobs wannabees. In fact, Lick was terminally modest. “If someone stole an idea from him,” said his wife Louise, “I’d pound the table and say it’s not fair, and he’d say, ‘It doesn’t matter who gets the credit. It matters that it gets done.'”

His unwillingness to blow his own horn is undoubtedly one of the contributing factors to Lick’s being one of the most under-recognized of computing’s pioneers. He published relatively little, both because he hated to write and because he genuinely loved to see one of his protegees recognized for fleshing out and popularizing one of his ideas. Yet the fact remains that his vision of computing’s necessary immediate future was actually far more prescient than that of many of his more celebrated peers.

To understand that vision and the ways in which it contrasted with that of some of his colleagues, we should begin with Lick’s background. Born in 1915 in St. Louis, Missouri, the son of a Baptist minister, he grew up a boy who was good at just about everything, from sports to mathematics to auto mechanics, but already had a knack for never making anyone feel jealous about it. After much tortured debate and a few abrupt changes of course at university, he finally settled on studying psychology, and was awarded his master’s degree in the field from St. Louis’s Washington University in 1938. According to his biographer M. Mitchell Waldrop, the choice of majors made all the difference in what he would go on to do.

Considering all that happened later, Lick’s youthful passion for psychology might seem like an aberration, a sideline, a long diversion from his ultimate career in computers. But in fact, his grounding in psychology would prove central to his very conception of computers. Virtually all the other computer pioneers of his generation would come to the field in the 1940s and 1950s with backgrounds in mathematics, physics, or electrical engineering, technological orientations that led them to focus on gadgetry — on making the machines bigger, faster, and more reliable. Lick was unique in bringing to the field a deep appreciation for human beings: our capacity to perceive, to adapt, to make choices, and to devise completely new ways of tackling apparently intricate problems. As an experimental psychologist, he found these abilities every bit as subtle and as worthy of respect as a computer’s ability to execute an algorithm. And that was why to him, the real challenge would always lie in adapting computers to the humans who used them, thereby exploiting the strengths of each.

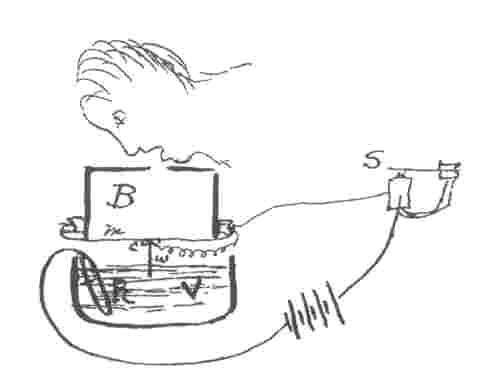

Still, Lick might very well have remained a “pure” psychologist if the Second World War hadn’t intervened. His pre-war research focus had been the psychological processes of human hearing. After the war began, this led him to Harvard University’s Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory, where he devised technologies to allow bomber crews to better communicate with one another inside their noisy airplanes. Thus he found the focus that would mark the rest of his career: the interaction between humans and technology. After moving to MIT in 1950, he joined the SAGE project, where he helped to design the user interface — not that the term yet existed! — which allowed the SAGE ground controllers to interact with the display screens in front of them; among his achievements here was the invention of the light pen. Having thus been bitten by the computing bug, he moved on in 1957 to Bolt Beranek and Newman, a computing laboratory and think tank with close ties to MIT.

He was still there in 1960, when he published perhaps the most important of all his rare papers, a piece entitled “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” in the journal Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics. In order to appreciate what a revolutionary paper it was, we should first step back to look at the view of computing to which it was responding.

The most typical way of describing computers in the mass media of the time was as “giant brains,” little different in qualitative terms from those of humans. This conception of computing would soon be all over pop culture — for example, in the rogue computers that Captain Kirk destroyed on almost a monthly basis on Star Trek, or in the computer HAL 9000, the villain of 2001: A Space Odyssey. A large number of computer researchers who probably ought to have known better subscribed to a more positive take on essentially the same view. Their understanding was that, if artificial intelligence wasn’t yet up to human snuff, it was only a matter of time. These proponents of “strong AI,” such as Stanford University’s John McCarthy and MIT’s own Marvin Minsky, were already declaring by the end of the 1950s that true computer consciousness was just twenty years away. (This would eventually lead to a longstanding joke in hacker culture, that strong AI is always exactly two decades away…) Even such an undeniable genius as Alan Turing, who had been dead six years already when Lick published his paper, had spent much effort devising a “Turing test” that could serve as a determiner of true artificial intelligence, and had attempted to teach a computer to play chess as a sort of opening proof of concept.

Lick, on the other hand, well recognized that to use the completely deterministic and algorithm-friendly game of chess for that purpose was not quite honest; a far better demonstration of artificial intelligence would be a computer that could win at poker, what with all of the intuition and social empathy that game required. But rather than chase such chimeras at all, why not let computers do the things they already do well and let humans do likewise, and teach them both to work together to accomplish things neither could on their own? Many of computing’s leading theorists, Lick implied, had developed delusions of grandeur, moving with inordinate speed from computers as giant calculators for crunching numbers to computers as sentient beings in their own right. They didn’t have to become the latter, Lick understood, to become one of the most important tools humanity had ever invented for itself; there was a sweet spot in between the two extremes. He chose to open his paper with a metaphor from the natural world, describing how fig trees are pollinated by the wasps which feed upon their fruit. “The tree and the insect are thus heavily interdependent,” he wrote. “The tree cannot reproduce without the insect; the insect cannot eat without the tree; they constitute not only a viable but a productive and thriving partnership.” A symbiosis, in other words.

A similar symbiosis could and should become the norm in human-computer interactions, with the humans always in the cat-bird seat as the final deciders — no Star Trek doomsday scenarios here.

[Humans] will set the goals and supply the motivations. They will formulate hypotheses. They will ask questions. They will think of mechanisms, procedures, and models. They will define criteria and serve as evaluators, judging the contributions of the equipment and guiding the general line of thought. The information-processing equipment, for its part, will convert hypotheses into testable models and then test the models against the data. The equipment will answer questions. It will simulate the mechanisms and models, carry out the procedures, and display the results to the operator. It will transform data, plot graphs. [It] will interpolate, extrapolate, and transform. It will convert static equations or logical statements into dynamic models so that the human operator can examine their behavior. In general, it will carry out the routinizable, clerical operations that fill the intervals between decisions.

Perchance in a bid not to offend his more grandiose colleagues, Lick did hedge his bets on the long-term prospects for strong artificial intelligence. It might very well arrive at some point, he said, although he couldn’t say whether that would take ten years or 500 years. Regardless, the years before its arrival “should be intellectually and creatively the most exciting in the history of mankind.”

In the end, however, even Lick’s diplomatic skills would prove insufficient to smooth out the differences between two competing visions of computing. By the end of the 1960s, the argument would literally split MIT’s computer-science research in two. One part would become the AI Lab, dedicated to artificial intelligence in its most expansive form; the other, known as the Dynamic Modeling Group, would take its mission statement as well as its name almost verbatim from Lick’s 1960 paper. For all that some folks still love to talk excitedly and/or worriedly of a “Singularity” after which computer intelligence will truly exceed human intelligence in all its facets, the way we actually use computers today is far more reflective of J.C.R. Licklider’s vision than that of Marvin Minsky or John McCarthy.

But all of that lay well in the future at the dawn of the 1960s. Viewing matters strictly through the lens of that time, we can now begin to see why Jack Ruina at ARPA found J.C.R. Licklider and the philosophy of computing he represented so appealing. Most of the generals and admirals Ruina talked to were much like the general public; they still thought of computers as giant brains that would crunch a bunch of data and then unfold for them the secrets of the universe — or at least of the Soviets. “The idea was that you take this powerful computer and feed it all this qualitative information, such as ‘the air-force chief drank two martinis’ or ‘Khrushchev isn’t reading Pravda on Mondays,'” laughed Ruina later. “And the computer would play Sherlock Holmes and reveal that the Russians must be building an MX-72 missile or something like that.” Such hopes were, as Lick put it to Ruina at their first meeting, “asinine.”

SAGE existed already as a shining example of Lick’s take on computers — computers as aids to rather than replacements for human intelligence. Ruina was well aware that command-and-control was one of the most difficult problems in warfare; throughout history, it has often been the principal reason that wars are won or lost. Just imagine what SAGE-like real-time information spaces could do for the country’s overall level of preparedness if spread throughout the military chain of command…

On October 1, 1962, following a long courtship on the part of Ruina, Lick officially took up his new duties in a small office in the Pentagon. Like Lick himself, Ruina wasn’t much for micromanagement; he believed in hiring smart people and stepping back to let them do their thing. Thus he turned over his $10 million per year to Lick with basically no strings attached. Just find a way to make interactive computing better, he told him, preferably in ways useful to the military. For his part, Lick made it clear that “I wasn’t doing battle planning,” as he later remembered. “I was doing the technical substrate that would one day support battle planning.” Ruina said that was just fine with him. Lick had free rein.

Ironically, he never did do much of anything with the leftover SAGE computers that had gotten the whole ball rolling; they were just too old, too specialized, too big. Instead he set about recruiting the smartest people he knew of to do research on the government’s dime, using the equipment found at their own local institutions.

If I tried to describe everything these folks got up to here, I would get hopelessly sidetracked. So, we’ll move directly to ARPA’s most famous computing project of all. A Licklider memo dated April 25, 1963, is surely one of the most important of its type in all of modern history. For it was here that Lick first made his case for a far-flung general-purpose computer network. The memo was addressed to “members and affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network,” which serves as an example of Lick’s tendency to attempt to avoid sounding too highfalutin by making the ideas about which he felt most strongly sound a bit ridiculous instead. Strictly speaking, the phrase “Intergalactic Computer Network” didn’t apply to the thing Lick was proposing; the network in question here was rather the human network of researchers that Lick was busily assembling. Nevertheless, a computer network was the topic of the memo, and its salutation and its topic would quickly become conflated. Before it became the Internet, even before it became the ARPANET, everyone would call it the Intergalactic Network.

In the memo, Lick notes that ARPA is already funding a diverse variety of computing projects at an almost equally diverse variety of locations. In the interest of not duplicating the wheel, it would make sense if the researchers involved could share programs and data and correspond with one another easily, so that every researcher could benefit from the efforts of the others whenever possible. Therefore he proposes that all of their computers be tied together on a single network, such that any machine can communicate at any time with any other machine.

Lick was careful to couch his argument in the immediate practical benefits it would afford to the projects under his charge. Yet it arose from more abstract discussions that had been swirling around MIT for years. Lick’s idea of a large-scale computer network was in fact inextricably bound up with his humanist vision for computing writ large. In a stunningly prescient article published in the May 1964 issue of Atlantic Monthly, Martin Greenberger, a professor with MIT’s Sloan School of Management, made the case for a computer-based “information utility” — essentially, for the modern Internet, which he imagined arriving at more or less exactly the moment it really did become an inescapable part of our day-to-day lives. In doing all of this, he often seemed to be parroting Lick’s ideology of better living through human-computer symbiosis, to the point of employing many of the same idiosyncratic word choices.

The range of application of the information utility includes medical-information systems for hospitals and clinics, centralized traffic controls for cities and highways, catalogue shopping from a convenient terminal at home, automatic libraries linked to home and office, integrated management-control systems for companies and factories, teaching consoles in the classroom, research consoles in the laboratory, design consoles in the engineering firm, editing consoles in the publishing office, [and] computerized communities.

Barring unforeseen obstacles, an online interactive computer service, provided commercially by an information utility, may be as commonplace by 2000 AD as a telephone service is today. By 2000 AD, man should have a much better comprehension of himself and his system, not because he will be innately any smarter than he is today, but because he will have learned to use imaginatively the most powerful amplifier of intelligence yet devised.

In 1964, the idea of shopping and socializing through a home computer “sounded a bit like working a nuclear reactor in your home,” as M. Mitchell Waldrop writes. Still, there it was — and Greenberger’s uncannily accurate predictions almost certainly originated with Lick.

Lick himself, however, was about to step back and entrust his dream to others. In September of 1964, he resigned from his post in the Pentagon to accept a job with IBM. There were likely quite a number of factors behind this decision, which struck many of his colleagues at the time as perplexing as it strikes us today. As we’ve seen, he was not a hardcore techie, and he may have genuinely believed that a different sort of mind would do a better job of managing the projects he had set in motion at ARPA. Meanwhile his family wasn’t overly thrilled at life in their cramped Washington apartment, the best accommodations his government salary could pay for. IBM, on the other hand, compensated its senior employees very generously — no small consideration for a man with two children close to university age. After decades of non-profit service, he may have seen this, reasonably enough, as his chance to finally cash in. Lastly and perhaps most importantly, he probably truly believed that he could do a lot of good for the world at IBM, by convincing this most powerful force in commercial computing to fully embrace his humanistic vision of computing’s potential. That wouldn’t happen in the end; his tenure there would prove short and disappointing. He would find the notoriously conservative culture of IBM impervious to his charms, a thoroughly novel experience for him. But of course he couldn’t know that prior to the fact.

Lick’s successor at ARPA was Ivan Sutherland, a young man of just 26 years who had recently created a sensation at MIT with his PhD project, a program called Sketchpad that let a user draw arbitrary pictures on a computer screen using one of the light pens that Lick had helped to invent for SAGE. But Sutherland proved no more interested in the details of administration than Lick had been, even as he demonstrated why a more typical hacker type might not have been the best choice for the position after all, being too fixated on his own experiments with computer graphics to have much time to inspire and guide others. Lick’s idea for a large-scale computer network lay moribund during his tenure. It remained so for almost two full years in all, until Sutherland too left what really was a rather thankless job. His replacement was one Robert Taylor. Critically, this latest administrator came complete with Lick’s passion for networking, along with something of his genius for interpersonal relations.

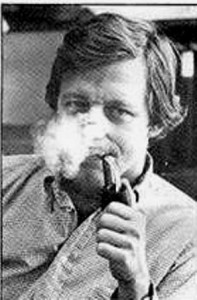

Robert Taylor, as photographed by Annie Leibowitz in 1972 for a Rolling Stone feature article on Xerox PARC, his destination after leaving ARPA.

Coming on as a veritable stereotype of a laid-back country boy, right down to his laconic Texan accent, Robert Taylor was a disarmingly easy man to underestimate. He was born seventeen years after Lick, but there were some uncanny similarities in their backgrounds. Taylor too grew up far from the intellectual capitals of the nation as the son of a minister. Like Lick, he gradually lost his faith in the course of trying to decide what to do with his life, and like Lick he finally settled on psychology. More or less, anyway; he graduated from the University of Texas at age 25 in 1957 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and minors in mathematics, philosophy, English, and religion. He was working at Martin Marietta in a “stopgap” job in the spring of 1960, when he stumbled across Lick’s article on human-computer symbiosis. It changed his life. “Lick’s paper opened the door for me,” he says. “Over time, I became less and less interested in brain research, and more and more heartily subscribed to the Licklider vision of interactive computing.” The interest led him to NASA the following year, where he helped to design the displays used by ground controllers on the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo manned-spaceflight programs. In early 1965, he moved to ARPA as Sutherland’s deputy, then took over Sutherland’s job following his departure in June of 1966.

In the course of it all, Taylor got to talk with Lick himself on many occasions. Unsurprisingly given the similarities in their backgrounds and to some extent in their demeanors, the two men hit it off famously. Soon Taylor felt the same zeal that his mentor did for a new, unprecedentedly large and flexible computer network. And once he found himself in charge of ARPA’s computer-research budget, he was in a position to do something about it. He was determined to make Lick’s Intergalactic Network a reality.

Alas, instilling the same determination in the researchers working with ARPA would not be easy. Many of them would later be loath to admit their reluctance, given that the Intergalactic Network would prove to be one of the most important projects in the entire history of computing, but it was there nonetheless. Severo Ornstein, who was working at Lick’s old employer of Bolt Beranek and Newman at this time, confesses to a typical reaction: “Who would want such a thing?” Computer cycles were a precious resource in those days, a commodity which researchers coveted for their personal use as much as Scrooge coveted his shillings. Almost no one was eager to share their computers with people in other cities and states. The strong AI contingent under Minsky and McCarthy, whose experiments not coincidentally tended to be especially taxing on a computer’s resources, were among the loudest objectors. It didn’t help matters that Taylor suffered from something of a respect deficit. Unlike Lick and Sutherland before him, he wasn’t quite of this group of brainy and often arrogant cats which he was attempting to herd, having never made a name for himself through research at one of their universities — indeed, lacking even the all-important suffix “PhD” behind his name.

But Bob Taylor shared one more similarity with J.C.R. Licklider: he was all about making good things happen, not about taking credit for them. If the nation’s computer researchers refused to take him seriously, he would find someone else whom they couldn’t ignore. He settled on Larry Roberts, an MIT veteran who had helped Sutherland with Sketchpad and done much groundbreaking work of his own in the field of computer graphics, such as laying the foundation for the compressed file formats that are used to shuffle billions of images around the Internet today. Roberts had been converted by Lick to the networking religion in November of 1964, when the two were hanging out in a bar after a conference. Roberts:

The conversation was, what was the future? And Lick, of course, was talking about his concept of an Intergalactic Network.

At that time, Ivan [Sutherland] and I had gone farther than anyone else in graphics. But I had begun to realize that everything I did was useless to the rest of the world because it was on the TX-2, and that was a unique machine. The TX-2, [the] CTSS, and so forth — they were all incompatible, which made it almost impossible to move data. So everything we did was almost in isolation. The only thing we could do to get the stuff out into the world was to produce written technical papers, which was a very slow process.

It seemed to me that civilization would change if we could move all this [over a network]. It would be a whole new way of sharing knowledge.

The only problem was that Roberts had no interest in becoming a government bureaucrat. So Taylor, whose drawl masked a steely resolve when push came to shove, did what he had to in order to get his man. He went to the administrators of MIT and Lincoln Lab, which were heavily dependent on government funding, and strongly hinted that said funding might be contingent on one member of their staff stepping away from his academic responsibilities for a couple of years. Before 1966 was out, Larry Roberts reported for duty at the Pentagon, to serve as the technical lead of what was about to become known as the ARPANET.

In March of 1967, as the nation’s adults were reeling from the fiery deaths of three Apollo astronauts on the launchpad and its youth were ushering in the Age of Aquarius, Taylor and Roberts brought together 25 or so of the most brilliant minds in computing in a University of Michigan classroom in the hope of fomenting a different sort of revolution. Despite the addition of Roberts to the networking cause, most of them still didn’t want to be there, thought this ARPANET business a waste of time. They arrived all too ready to voice objections and obstacles to the scheme, of which there were no shortage.

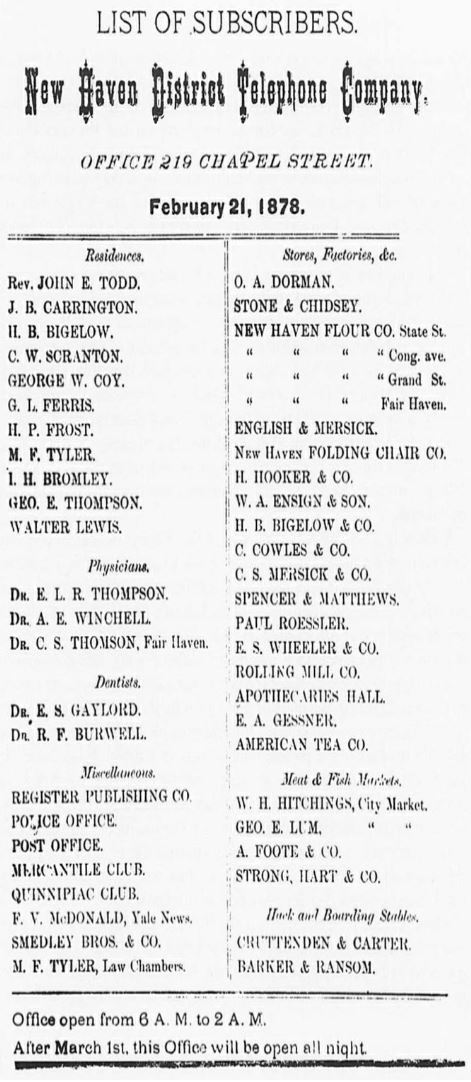

The computers that Taylor and Roberts proposed to link together were a motley crew by any standard, ranging from the latest hulking IBM mainframes to mid-sized machines from companies like DEC to bespoke hand-built jobs. The problem of teaching computers from different manufacturers — or even different models of computer from the same manufacturer — to share data with one another had only recently been taken up in earnest. Even moving text from one machine to another could be a challenge; it had been just half a decade since a body called the American Standards Association had approved a standard way of encoding alphanumeric characters as binary numbers, constituting the computer world’s would-be equivalent to Morse Code. Known as the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, or ASCII, it was far from universally accepted, with IBM in particular clinging obstinately to an alternative, in-house-developed system known as the Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code, or EBCDIC. Uploading a text file generated on a computer that used one standard to a computer that used the other would result in gibberish. How were such computers to talk to one another?

The ARPANET would run on ASCII, Taylor and Roberts replied. Those computers that used something else would just have to implement a translation layer for communicating with the outside world.

Fair enough. But then, how was the physical cabling to work? ARPA couldn’t afford to string its own wires all over the country, and the ones that already existed were designed for telephones, not computers.

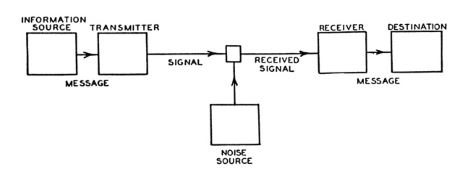

No problem, came the reply. ARPA would be able to lease high-capacity lines from AT&T, and Claude Shannon had long since taught them all that information was information. Naturally, there would be some degree of noise on the lines, but error-checking protocols were by now commonplace. Tests had shown that one could push information down one of AT&T’s best lines at a rate of up to 56,000 baud before the number of corrupted packets reached a point of diminishing returns. So, this was the speed at which the ARPANET would run.

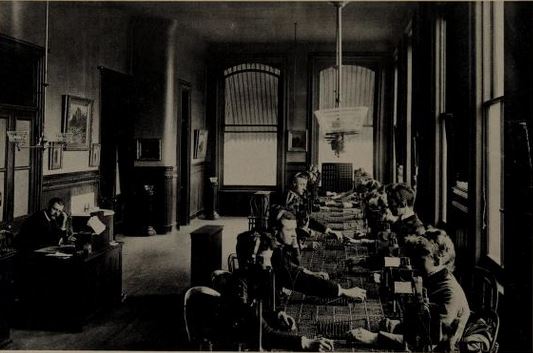

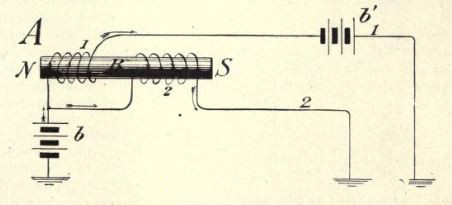

The next objection was the gnarliest. At the core of the whole ARPANET idea lay the stipulation that any computer on the network must be able to talk to any other, just like any telephone was able to ring up any other. But existing wide-area computer networks, such as the ones behind SAGE and Sabre, all operated on the railroad model of the old telegraph networks: each line led to exactly one place. To use the same approach as existing telephone networks, with individual computers constantly dialing up one another through electro-mechanical switches, would be way too inefficient and inflexible for a high-speed data network such as this one. Therefore Taylor and Roberts had another approach in mind.

We learned in the last article about R.W. Hamming’s system of error correction, which worked by sending information down a line as a series of packets, each followed by a checksum. In 1964, in a book entitled simply Communication Nets, an MIT researcher named Leonard Kleinrock extended the concept. There was no reason, he noted, that a packet couldn’t contain additional meta-information beyond the checksum. It could, for example, contain the destination it was trying to reach on a network. This meta-information could be used to pass it from hand to hand through the network in the same way that the postal system used the address on the envelope of a paper letter to guide it to its intended destination. This approach to data transfer over a network would soon become known as “packet switching,” and would prove of incalculable importance to the world’s digital future.[1]As Kleinrock himself would hasten to point out, he was not the sole originator of the concept, which has a long and somewhat convoluted history as a theory. His book was, however, the way that many or most of the folks behind the ARPANET first encountered packet switching.

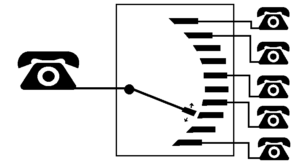

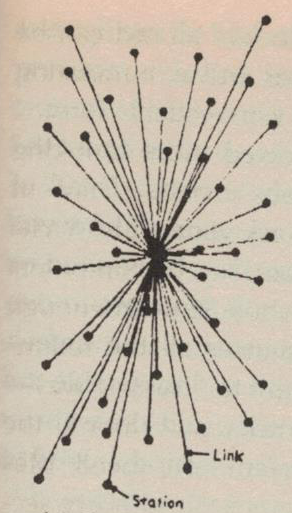

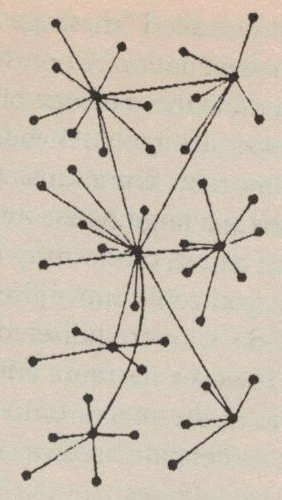

A “star” network topology, in which every computer communicates with every other by passing packets through a single “Grand Central Station.”

How exactly might packet switching work on the ARPANET? At first, Taylor and Roberts had contemplated using a single computer as a sort of central postal exchange. Every other computer on the ARPANET would be wired into this machine, whose sole duty would be to read the desired destination of each incoming packet and send it there. But the approach came complete with a glaring problem: if the central hub went down for any reason, it would take the whole ARPANET down with it.

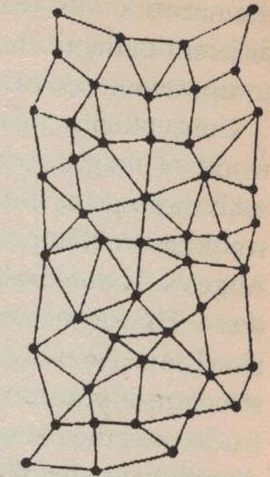

A “distributed” network topology in which all of the computers work together to move messages through the system. It lacks a single point of failure, but is much more complicated to implement from a technical perspective.

Instead Taylor and Roberts settled on a radically de-centralized approach. Each computer would be directly connected to no more than a handful of other machines. When it received a packet from one of them, it would check the address. If it was not the intended final destination, it would consult a logical map of the network and send the packet along to the peer computer able to get it there most efficiently; then it would forget all about it and go about its own business again. The advantage of the approach was that, if any given computer went down, the others could route their way around it until it came online again. Thus there would be no easy way to “break” the ARPANET, since there would be no single point of failure. This quality of being de-centralized and self-correcting remains the most important of all the design priorities of the modern Internet.

Everyone at the meeting could agree that all of this was quite clever, but they still weren’t won over. The naysayers’ arguments still hinged on how precious computing horsepower was. Every nanosecond a computer spent acting as an electronic postal sorter was a nanosecond that computer couldn’t spend doing other sorts of more useful work. For once, Taylor and Roberts had no real riposte for this concern, beyond vague promises to invest ARPA funds into more and better computers for those who had need of them. Then, just as the meeting was breaking up, with skepticism still hanging palpably in the air, a fellow named Wesley Clark passed a note to Larry Roberts, saying he thought he had a solution to the problem.

It seemed to him, he elaborated to Taylor and Roberts after the meeting, that running the ARPANET straight through all of its constituent machines was rather like running an interstate highway system right through the center of every small town in the country. Why not make the network its own, largely self-contained thing, connected to each computer it served only by a single convenient off- and on-ramp? Instead of asking the computer end-users of the ARPANET to also direct its flow of traffic, one could use dedicated machines as the traffic wardens on the highway itself. These “Interface Message Processors,” or IMPs, would be able to move packets through the system quickly, without taxing the other computers. And they too could allow for a non-centralized, fail-safe network if they were set up the right way. Today IMPs are known as routers, but the principle of their operation remains the same.

A network that uses the IMPs proposed by Wesley Clark. Each IMP sits at the center of a cluster of computers, and is also able to communicate with its peers to send messages to computers on other clusters. A failed IMP actually can take a substantial chunk of the network offline under the arrangement shown here, but redundant IMPs and connections between them all could and eventually would be built into the design.

When Wesley Clark spoke, people listened; his had been an important voice in hacker circles since the days of MIT’s Project Whirlwind. Taylor and Roberts immediately saw the wisdom in his scheme.

The advocacy of the highly respected Clark, combined with the promise that ARPANET need not cost them computer cycles if it used his approach, was enough to finally bring most of the rest of the research community around. Over the months that followed, while Taylor and Roberts worked out a project plan and budget, skepticism gradually morphed into real enthusiasm. J.C.R. Licklider had by now left IBM and returned to the friendlier confines of MIT, whence he continued to push the ARPANET behind the scenes. Especially the younger generation that was coming up behind the old guard tended to be less enamored with the “giant brain” model of computing and more receptive to Lick’s vision, and thus to the nascent ARPANET. “We found ourselves imagining all kinds of possibilities [for the ARPANET],” remembers one Steve Crocker, a UCLA graduate student at the time. “Interactive graphics, cooperating processes, automatic database query, electronic mail…”

In the midst of the building buzz, Lick and Bob Taylor co-authored an article which appeared in the April 1968 issue of the journal Science and Technology. Appropriately entitled “The Computer as a Communications Device,” it included Lick’s most audacious and uncannily accurate prognostications yet, particularly when it came to the sociology, if you will, of its universal computer network of the future.

What will online interactive communities be like? They will consist of geographically separated members. They will be communities not of common location but of common interest [emphasis original]…

Each secretary’s typewriter, each data-gathering instrument, conceivably each Dictaphone microphone, will feed into the network…

You will not send a letter or a telegram; you will simply identify the people whose files should be linked to yours — and perhaps specify a coefficient of urgency. You will seldom make a telephone call; you will ask the network to link your consoles together…

You will seldom make a purely business trip because linking consoles will be so much more efficient. You will spend much more time in computer-facilitated teleconferences and much less en route to meetings…

Available within the network will be functions and services to which you subscribe on a regular basis and others that you call for when you need them. In the former group will be investment guidance, tax counseling, selective dissemination of information in your field of specialization, announcement of cultural, sport, and entertainment events that fit your interests, etc. In the latter group will be dictionaries, encyclopedias, indexes, catalogues, editing programs, teaching programs, testing programs, programming systems, databases, and — most important — communication, display, and modeling programs…

When people do their informational work “at the console” and “through the network,” telecommunication will be as natural an extension of individual work as face-to-face communication is now. The impact of that fact, and of the marked facilitation of the communicative process, will be very great — both on the individual and on society…

Life will be happier for the online individual because the people with whom one interacts most strongly will be selected more by commonality of interests and goals than by accidents of proximity. There will be plenty of opportunity for everyone (who can afford a console) to find his calling, for the whole world of information, with all its fields and disciplines, will be open to him…

For the society, the impact will be good or bad, depending mainly on the question: Will “to be online” be a privilege or a right? If only a favored segment of the population gets to enjoy the advantage of “intelligence amplification,” the network may exaggerate the discontinuity in the spectrum of intellectual opportunity…

On the other hand, if the network idea should prove to do for education what a few have envisioned in hope, if not in concrete detailed plan, and if all minds should prove to be responsive, surely the boon to humankind would be beyond measure…

The dream of a nationwide, perhaps eventually a worldwide web of computers fostering a new age of human interaction was thus laid out in black and white. The funding to embark on at least the first stage of that grand adventure was also there, thanks to the largess of the Cold War military-industrial complex. And solutions had been proposed for the thorniest technical problems involved in the project. Now it was time to turn theory into practice. It was time to actually build the Intergalactic Computer Network.

(Sources: the books A Brief History of the Future: The Origins of the Internet by John Naughton; Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet by Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution by Steven Levy, From Gutenberg to the Internet: A Sourcebook on the History of Information Technology edited by Jeremy M. Norman, The Dream Machine by M. Mitchell Waldrop, A History of Modern Computing (2nd ed.) by Paul E. Ceruzzi, Communication Networks: A Concise Introduction by Jean Walrand and Shyam Parekh, Communication Nets by Leonard Kleinrock, and Computing in the Middle Ages by Severo M. Ornstein. Online sources include the companion website to Where Wizards Stay Up Late and “The Computers of Tomorrow” by Martin Greenberger on The Atlantic Online.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | As Kleinrock himself would hasten to point out, he was not the sole originator of the concept, which has a long and somewhat convoluted history as a theory. His book was, however, the way that many or most of the folks behind the ARPANET first encountered packet switching. |

|---|