Mosaic Communications was founded on $13 million in venture capital, a pittance by the standards of today but an impressive sum by those of 1994. Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark’s business plan, if you can call it that, would prove as emblematic of the era of American business history they were inaugurating as anything they ever did. “I don’t know how in hell we’re going to make money,” mused Clark, “but I’ll put money behind it, and we’ll figure out a way. A market growing as quickly as that [one] is going to have money to be made in it.” This naïve faith that nebulous user “engagement” must inevitably be transformed into dollars in the end by some mysterious alchemical process would be all over Silicon Valley throughout the dot-com boom — and, indeed, has never entirely left it even after the bust.

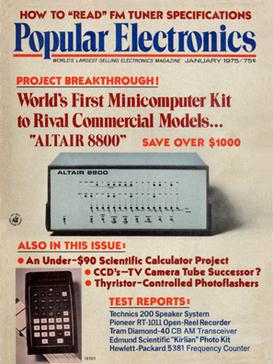

Andreessen and Clark’s first concrete action after the founding was to contact everyone at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications who had helped out with the old Mosaic browser, asking them to come to Silicon Valley and help make the new one. Most of their targets were easily tempted away from the staid nonprofit by the glamor of the most intensely watched tech startup of the year, not to mention the stock options that were dangled before them. The poaching of talent from NCSA secured for the new company some of the most seasoned browser developers in the world. And, almost as importantly, it also served to cut NCSA’s browser — the new one’s most obvious competition — off at the knees. For without these folks, how was NCSA to keep improving its browser?

The partners were playing a very dangerous game here. The Mosaic browser and all of its source code were owned by NCSA as an organization. Not only had Andreessen and Clark made the cheeky move of naming their company after a browser they didn’t own, but they had now stolen away from NCSA those people with the most intimate knowledge of how said browser actually worked. Fortunately, Clark was a grizzled enough veteran of business to put some safeguards in place. He was careful to ensure that no one brought so much as a line of code from the old browser with them to Mosaic Communications. The new one would be entirely original in terms of its code if not in terms of the end-user experience; it would be what the Valley calls a “clean-room implementation.”

Andreessen and Clark were keenly aware that the window of opportunity to create the accepted successor to NCSA Mosaic must be short. They made it clearer with every move they made that they saw the World Wide Web as a zero-sum game. They consciously copied the take-no-prisoners approach of Bill Gates, CEO of Microsoft, which had by now replaced IBM as the most powerful and arguably the most hated company in the computer industry. Marc Andreessen:

We knew that the key to success for the whole thing was getting ubiquity on the [browser] side. That was the way to get the company jump-started because that gives you essentially a broad platform to build off of. It’s basically a Microsoft lesson, right? If you get ubiquity, you have a lot of options, a lot of ways to benefit from that. You can get paid by the product that you are ubiquitous on, but you can also get paid on products that benefit as a result. One of the fundamental lessons is that market share now equals revenue later, and if you don’t have the market share now, you are not going to have revenue later. Another fundamental lesson is that whoever gets the volume does win in the end. Just plain wins. There has to be just one single winner in a market like this.

The founders pushed their programmers hard, insisting that the company simply had to get the browser out by the fall of 1994, which gave them a bare handful of months to create it from scratch. To spur their employees on, they devised a semi-friendly competition. They divided the programmers into three teams, one working on a browser for Unix, one on the Macintosh version, and one on the Microsoft Windows version. The teams raced one another from milestone to milestone, and compared their browsers’ rendering speeds down to the millisecond, all for weekly bragging rights and names on walls of fame and/or shame. One mid-level manager remembers how “a lot of times, people were there 48 hours straight, just coding. I’ve never seen anything like it, in terms of honest-to-God, no BS, human endurance.” Inside the office, the stakes seemed almost literally life or death. He recalls an attitude that “we were fighting some war and that we could win.”

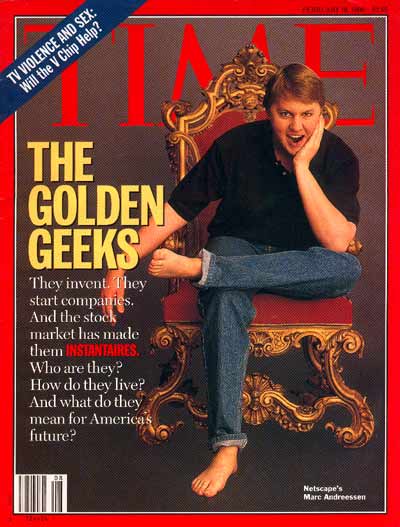

In the meantime, Jim Clark was doing some more poaching. He hired away from his old company Silicon Graphics an ace PR woman named Rosanne Siino. She became the mass-media architect of the dot-com founder as genius, visionary, and all-around rock star. “We had this 22-year-old kid who was pretty damn interesting, and I thought, ‘There’s a story here,'” she says. She proceeded to pitch that story to anyone who would take her calls.

Andreeseen, for his part, slipped into his role fluidly enough after just a bit of coaching. “If you get more visible,” he reasoned, “it counts as advertising, and it doesn’t cost anything.” By the mid-summer of 1994, he was doing multiple interviews most days. Tall and athletically built, well-dressed and glib — certainly no one’s stereotype of a pasty computer nerd — he was perfect fodder for tech journals, mainstream newspapers, and supermarket tabloids alike. “He’s young, he’s hot, and he’s here!” trumpeted one of the last above a glamor shot of the wunderkind.

The establishment business media found the rest of the company to be almost as interesting if not quite as sexy, from its other, older founder who was trying to make lightning strike a second time to the fanatical young believers who filled the cubicles; stories of crunch time were more novel then than they would soon become. Journalists fixated on the programmers’ whimsical mascot, a huge green and purple lizard named Mozilla who loomed over the office from his perch on one wall. Some were even privileged to learn that his name was a portmanteau of “Mosaic” and “Godzilla,” symbolizing the company’s intention to annihilate the NCSA browser as thoroughly as the movie monster had leveled Tokyo. On the strength of sparkling anecdotes like this, Forbes magazine named Mosaic Communications one of its “25 Cool Companies” — all well before it had any products whatsoever.

Mozilla, the unofficial mascot of Mosaic (later Netscape) Communications. He would prove to be far longer-lived than the company he first represented. Today he still lends his name to the Mozilla Foundation, which maintains an open-source browser and fights for open standards on the Web — somewhat ironically, given that the foundation’s origins lie in the first company to be widely perceived as a threat to those standards.

The most obvious obstacle to annihilating the NCSA browser was the latter’s price: it was, after all, free. Just how was a for-profit business supposed to compete with that price point? Andreeseen and Clark settled on a paid model that nevertheless came complete with a nudge and a wink. The browser they called Mosaic Netscape would technically be free only to students and educators. But others would be asked to pay the $39 licensing fee only after a 90-day trial period — and, importantly, no mechanism would be implemented to coerce them into doing so even after the trial expired. Mosaic Communications would thus make the cornerstone of its business strategy Andreessen’s sanguine conviction that “market share now equals revenue later.”

Mosaic Netscape went live on the Internet on October 13, 1994. And in terms of Andreessen’s holy grail of market share at least, it was an immediate, thumping success. Within weeks, Mosaic Netscape had replaced NCSA Mosaic as the dominant browser on the Web. In truth, it had much to recommend it. It was blazing fast on all three of the platforms on which it ran, a tribute to the fierce competition between the teams who had built its different versions. And it sported some useful new HTML tags, such as “<center>” for centering text and “<blink>” for making it do just that. (Granted, the latter was rather less essential than the former, but that wouldn’t prevent thousands of websites from hastening to make use of it; as is typically the case with such things, the evolution of Web aesthetics would happen more slowly than that of Web technology.) Most notably of all, Netscape added the possibility of secure encryption to the Web, via the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). The company rightly considered SSL to be an essential prerequisite to online commerce; no one in their right mind was going to send credit-card numbers in the clear.

But, valuable though these additions (mostly) were, they raised the ire of many of those who had shepherded the Web through its early years, not least among them Tim Berners-Lee. Although they weren’t patented and thus weren’t proprietary in a legal sense — anyone was free to implement them if they could figure out how they worked — Mosaic Communications had rolled them out without talking to anyone about what they were doing, leaving everyone else to play catch-up in a race of their making.

Still, such concerns carried little weight with most users. They were just happy to have a better browser.

More pressing for Andreessen and Clark were the legal threats that were soon issuing from NCSA and the University of Illinois, demanding up to 50 percent of the revenue from Mosaic Netscape, which they alleged was by rights at least half theirs. These continued even after Jim Clark produced a report from a forensic software expert which stated that, for all that they might look and feel the same, NCSA Mosaic and Mosaic Netscape shared no code at all. Accepting at last that naming their company after the rival browser whose code they insisted they were not stealing had been terrible optics, Andreessen and Clark rechristened Mosaic Communications as Netscape Communications on November 14, 1994; its browser now became known as Netscape Navigator. Seeking a compromise to make the legal questions go away once and for all, Clark offered NCSA a substantial amount of stock in Netscape, only to be turned down flat. In the end, he agreed to a cash settlement instead; industry rumor placed it in the neighborhood of $2 million. NCSA and the university with which it was affiliated may have have felt validated by the settlement, but time would show that it had not been an especially wise decision to reject Clark’s first overture: ten months later, the stock NCSA had been offered was worth $17 million.

For all its exciting growth, the World Wide Web had made relatively few inroads with everyday Americans to this point. But all of that changed in 1995, the year when the Web broke through in earnest. There was now enough content there to make it an interesting place for the ordinary Joe or Jane to visit, as well as a slick, user-friendly browser for him or her to use in Netscape Navigator.

Just as importantly, there were for the first time enough computers in daily use in American homes to make something like the Web a viable proposition. With the more approachable Microsoft Windows having replaced the cryptic, command-line-driven MS-DOS as the typical face of consumer computing, with new graphics card, sound cards, and CD-ROM drives providing a reasonably pleasing audiovisual experience, with the latest word processors and spreadsheets being more powerful and easier to use than ever before, and with the latest microprocessors and hard drives allowing it all to happen at a reasonably brisk pace, personal computers had crossed a Rubicon in the last half-decade or so, to become gadgets that people who didn’t find computers themselves intrinsically fascinating might nonetheless want to own and use. Netscape Navigator was fortunate enough to hit the scene just as these new buyers were reaching a critical mass. They served to prime the pump. And then, once just about everyone with a computer seemed to be talking about the Web, the whole thing became a self-reinforcing virtuous circle, with computer owners streaming onto the Web and the Web in turn driving computer sales. By the summer of 1995, Netscape Navigator had been installed on at least 10 million computers.

Virtually every major corporation in the country that didn’t have a homepage already set one up during 1995. Many were little more than a page or two of text and a few corporate logos at this point, but a few did go further, becoming in the process harbingers of the digital future. Pizza Hut, for example, began offering an online ordering service in select markets, and Federal Express made it possible for customers to track the progress of their packages around the country and the world from right there in their browsers. Meanwhile Silicon Valley and other tech centers played host to startup after startup, including plenty of names we still know well today: the online bookstore (and later anything-store) Amazon, the online auction house eBay, and the online dating service Match.com among others were all founded this year.

Recognizing an existential threat when they saw one, the old guard of circumscribed online services such as CompuServe, who had pioneered much of the social and commercial interaction that was now moving onto the open Web, rushed to devise hybrid business models that mixed their traditional proprietary content with Internet access. Alas, it would avail most of them nothing in the end; the vast majority of these dinosaurs would shuffle off to extinction before the decade was out. Only an upstart service known as America Online, a comparative latecomer on the scene, would successfully weather the initial storm, thanks mostly to astute marketing that positioned it as the gentler, friendlier, more secure alternative to the vanilla Web for the non-tech-savvy consumer. Its public image as a sort of World Wide Web with training wheels would rake in big profits even as it made the service and its subscribers objects of derision for Internet sophisticates. But even America Online would not be able to maintain its stranglehold on Middle America forever. By shortly after the turn of the millennium — and shortly after an ill-advised high-profile merger with the titan of old media Time Warner — it too would be in free fall.

One question stood foremost in the minds of many of these millions who were flocking onto the Web for the first time: how the heck were they supposed to find anything here? It was, to be sure, an ironic question to be asking, given that Tim Berners-Lee had invented his World Wide Web for the express purpose of making the notoriously confounding pre-Web Internet easier to navigate. Yet as websites bred and spawned like rabbits in a Viagra factory, it became a relevant one once again.

The idea of a network of associative links was as valid as ever — but just where were you to start when you knew that you wanted to, say, find out the latest rumors about your favorite band Oasis? (This was the mid-1990s, after all.) Once you were inside the Oasis ecosystem, as it were, it was easy enough to jump from site to site through the power of association. But how were you to find your way inside in the first place when you first fired up your browser and were greeted with a blank page and a blank text field waiting for you to type in a Web address you didn’t know?

One solution to this conundrum was weirdly old-fashioned: brick-and-mortar bookstore shelves were soon filling up with printed directories that cataloged the Web’s contents. But this was a manifestly inadequate solution as well as a retrograde one; what with the pace of change on the Web, such books were out of date before they were even sold. What people really needed was a jumping-off point on the Web itself, a home base from which to start each journey down the rabbit hole of their particular interests, offering a list of places to go that could grow and change as fast as the Web itself. Luckily, two young men with too much time on their hands had created just such a thing.

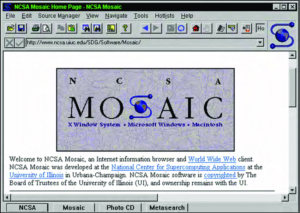

Jerry Yang and David Filo were rather unenthusiastic Stanford graduate students in computer science during the early 1990s. Being best friends, they discovered the Web together shortly after the arrival of the NCSA Mosaic browser. Already at this early date, finding the needles in the digital haystack was becoming difficult. Therefore they set up a list of links they found interesting, calling it “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web.” This was not unique in itself; thousands of others were putting up similar lists of “cool links.” Yang and Filo were unique, however, in how much energy they devoted to the endeavor.

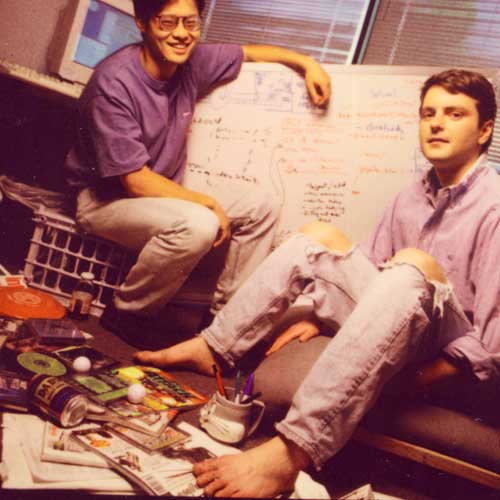

Jerry Yang and David Filo. Bare feet were something of a staple of Silicon Valley glamor shots, serving as a delightful shorthand for informal eccentricity in the eyes of the mass media.

They were among the first wave of people to discover the peculiar, dubiously healthy dopamine-release mechanism that is online attention, whether measured in page views, as in those days, or likes or retweets, as today. The more traffic that came their way, the more additional traffic they wanted. Instead of catering merely to their personal interests, they gradually turned their site into a comprehensive directory of the Web — all of it, in the ideal at least. They surfed tirelessly day after day, neglecting girlfriends, family, and personal hygiene, not to mention their coursework, trying to keep up with the Sisyphean task of cataloging every new site of note that went up on the Web, then slotting it into a branching hierarchy of hundreds of categories and sub-categories.

In April of 1994, they decided that their site needed a catchier name. Their initial thought was to combine their last names in some ingenious way, but they couldn’t find one that worked. So, they focused on the name of Yang, by nature the more voluble and outgoing of the pair. They were steeped enough in hacker culture to think of a popular piece of software called YACC; it stood for “Yet Another Compiler Compiler,” but was pronounced like the Himalayan beast of burden. That name was obviously taken, but perhaps they could come up with something else along those lines. They looked in a dictionary for words starting with “ya”: “yawn,” “yawp,” “yaw,” “y-axis”… “yahoo.” The good book told them that “yahoo” derived from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, where it referred to “any of a race of brutish, degraded creatures having the form and all of the vices of man.” Whatever — they just liked the sound of the word. They racked their brains until they had turned it into an acronym: “Yet Another Hierarchical Officious Oracle.” Whatever. It would do. A few months later, they stuck an exclamation point at the end as a finishing touch. And so Yahoo! came to be.

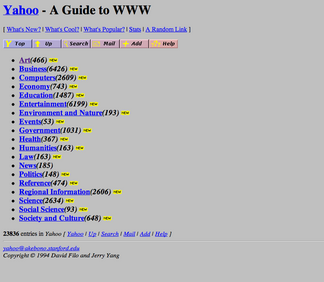

Yahoo! very shortly after it received its name, but before it received its final flourish of an exclamation point.

For quite some time after that, not much changed on the surface. Yang and Filo had by now appropriated a neglected camping trailer on one of Stanford’s back parking lots, which they turned into their squalid headquarters. They tried to keep up with the flood of new content coming onto the Web every day by living in the trailer, trading four-hour shifts with one another around the clock, working like demons for that sweet fix of ever-increasing page-view numbers. “There was nothing else in the world like it,” says Yang. “There was such camaraderie, it was like driving off a cliff.”

But there came a point, not long after the start of that pivotal Web year of 1995, when Yang and Filo had to recognize that they were losing their battle with new content. So, they set off in search of the funding they would need to turn what had already become in the minds of many the Web’s de-facto “front page” into a real business, complete with employees they could pay to do what they had been doing for free. They seriously considered joining America Online, then came even closer to signing on with Netscape, a company which had already done much for their popularity by placing their site behind a button displayed prominently by the Navigator browser. In the end, though, they opted to remain independent. In April of 1995, they secured $4 million in financing, thanks to a far-sighted venture capitalist named Mike Moritz, who made the deal in the face of enormous skepticism from his colleagues. “The venture community [had never] invested in anything that gave a product away for free,” he remembers.

Or had they? It all depended on how you looked at it. Yang and Filo noted that television broadcasters had been giving their product away for free for decades as far as the individual viewer was concerned, making their money instead by selling access to their captive audience to third-party advertisers. Why couldn’t the same thing work on the Web? The demographic that visited Yahoo! regularly was, after all, an advertiser’s dream, being largely comprised of young adults with disposable income, attracted to novelty and with enough leisure time to indulge that attraction.

So, advertising started appearing on Yahoo! very shortly after it became a real business. Adherents to the old, non-commercial Web ideal grumbled, and some of them left in a huff, but their numbers were dwarfed by the continuing flood of new Netizens, who tended to perceive the Web as just another form of commercial media and were thus unfazed when they were greeted with advertising there. With the help of a groundbreaking Web analytics firm known as I/PRO, Yahoo! came up with ways to target its advertisements ever more precisely to each individual user’s interests, which she revealed to the company whether she wanted to or not through the links she clicked. The Web, Yang and Filo were at pains to point out, was the most effective advertising environment ever to appear. Business journalist Robert H. Reid, who profiled Netscape, Yahoo!, I/PRO, and much of the rest of the early dot-com startup scene for a book published in 1997, summed up the advantages of online advertising thusly:

There is a limit to how targeted advertising can be in traditional media. [This is] because any audience that is larger than one, even a fairly small and targeted [audience], will inevitably have its diversity elements (certain readers of the [Wall Street] Journal’s C section surely do not care about new bond issues, while certain readers of Field and Stream surely do). The Web has the potential to let marketers overcome this because, as an interactive medium, it can enable them to target their messages with surgical precision. Database technology can allow entirely unique webpages to be generated and served in moments based upon what is known about a viewer’s background, interests, and prior trajectory through a site. A site with a diverse audience can therefore direct one set of messages to high-school boys and a wholly different one to retired women. Or it could go further than this — after all, not all retired women are interested in precisely the same things — and present each visitor with an entirely unique message or experience.

Then, too, on the Web advertisers could do more than try to lodge an impression in a viewer’s mind and hope she followed up on it later, as was the case with television. They could rather present an advertisement as a clickable link that would take her instantly to their own site, which she could browse to learn far more about their products than she ever could from a one-minute commercial, which she might even be able to use to buy their products then and there — instant gratification for everyone involved.

Unlike so many Web firms before and after it, Yahoo! became profitable right away on the strength of reasoning like that. Even when Netscape pulled the site from Navigator at the end of 1995, replacing it with another one that was willing to pay dearly for the privilege — another sign of the changing times — it only briefly affected Yahoo!’s overall trajectory. As far as the mainstream media was concerned, Yang and Filo — these two scruffy graduate students who had built their company in a camping trailer — were the best business story since the rise of Netscape. If anything, Jerry Yang’s personal history made Yahoo! an even more compelling exemplar of the American Dream: he had come to the United States from Taiwan at the age of ten, when the only word of English he knew was “shoe.” When Yang showed that he could be every bit as charming as Marc Andreessen, that only made the story that much better.

Declaring that Yahoo! was a media rather than a technology company, Yang displayed a flair for branding one would never expect from a lifelong student: “It’s an article of culture. This differentiates Yahoo!, makes it cool, and gives it a market premium.” Somewhat ironically given its pitch that online advertising was intrinsically better than television advertising, Yahoo! became the first of the dot-com startups to air television commercials, all of which concluded with a Gene Autry -soundalike yodeling the name, an unavoidable ear worm for anyone who heard it. A survey conducted in 1996 revealed that half of all Americans already knew the brand name — a far larger percentage than that which had actually ventured online by that point. It seems safe to say that Yahoo! was the most recognizable of all the early Web brands, more so even than Netscape.

Trailblazing though Yahoo!’s business model was in many ways, its approach to its core competency seems disarmingly quaint today. Yahoo! wasn’t quite a search engine in the way we think of such things; it was rather a collection of sanctioned links, hand-curated and methodically organized by a small army of real human beings. Well before television commercials like the one above had begun to air, the dozens of “surfers” it employed — many of them with degrees in library science — had been relieved of the burden of needing to go out and find new sites for themselves by their own site’s ubiquity. Owners of sites which wished to be listed were expected to fill out a form, then wait patiently for a few days or weeks for someone to get to their request and, if it passed muster, slot it into Yahoo!’s ever-blossoming hierarchy.

Yahoo! as it looked in October of 1996. A search field has recently been added, but it searches only Yahoo!’s hand-curated database of sites rather than the Web itself.

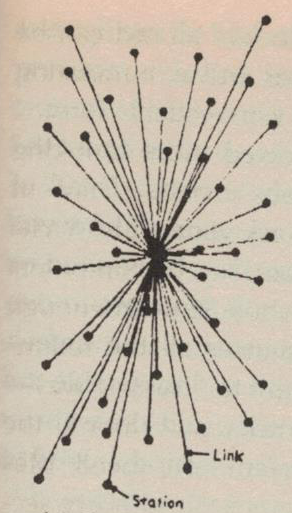

The alternative approach, which was common among Yahoo!’s competitors even at the time, is to send out automated “web crawlers,” programs that jump from link to link, in order to index all of the content on the Web into a searchable database. But as far as many Netizens were concerned in the mid-1990s, that approach just didn’t work all that well. A search for “Oasis” on one of these sites was likely to show you hundreds of pages dealing with desert ecosystems, all jumbled together with those dealing with your favorite rock band. It would be some time before search engines would be developed that could divine what you were really looking for based on context, that could infer from your search for “Oasis band” that you really, really didn’t want to read about deserts at that particular moment. Search engines like the one around which Google would later build its empire require a form of artificial intelligence — still not the computer consciousness of the old “giant brain” model of computing, but a more limited, context-specific form of machine learning — that would not be quick or easy to develop. In the meantime, there was Yahoo! and its army of human librarians.

And there were also the first Internet IPOs. As ever, Netscape rode the crest of the Web wave, the standard bearer for all to follow. On the eve of its IPO of August 9, 1995, it was decided to price the shares at $28 each, giving a total value to the company of over $1 billion, even though its total revenues to date amounted to $17 million and its bottom line to date tallied a loss of $13 million. Nevertheless, when trading opened the share price immediately soared to $74.75. “It took General Dynamics 43 years to become a corporation worth today’s $2.7 billion,” wrote The Wall Street Journal. “It took Netscape Communications about a minute.”

Yahoo!’s turn came on April 12, 1996. Its shares were priced at $13 when the day’s trading opened, and peaked at $43 over the course of that first day, giving the company an implied value of $850 million.

It was the beginning of an era of almost incomprehensible wealth generated by the so-called “Internet stocks,” often for reasons that were hard for ordinary people to understand, given how opaque the revenue models of so many Web giants could be. Even many of the beneficiaries of the stock-buying frenzy struggled to wrap their heads around it all. “Take, say, a Chinese worker,” said Lou Montulli, a talented but also ridiculously lucky programmer at Netscape. “I’m probably worth a million times the average Chinese worker, or something like that. It’s difficult to rationalize the value there. I worked hard, but did I really work that hard? I mean, can anyone work that hard? Is it possible? Is anyone worth that much?” Four of the ten richest people in the world today according to Forbes magazine — including the two richest of all — can trace the origins of their fortunes directly to the dot-com boom of the 1990s. Three more were already in the computer industry before the boom, and saw their wealth exponentially magnified by it. (The founders I’ve profiled in this article are actually comparatively small fish today. Their rankings on the worldwide list of billionaires as of this writing range from 792 in the case of David Filo to 1717 for Marc Andreessen.)

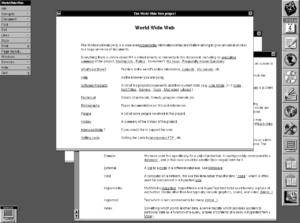

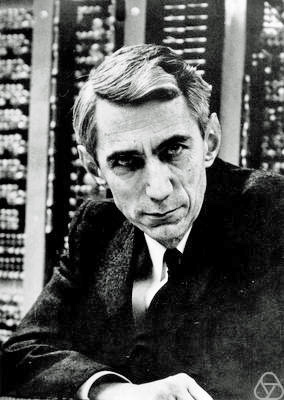

And what was Tim Berners-Lee doing as people began to get rich from his creation? He did not, as some might have expected, decamp to Silicon Valley to start a company of his own. Nor did he accept any of the “special advisor” roles that were his for the taking at a multitude of companies eager to capitalize on the cachet of his name. He did leave CERN, but made it only as far as Boston, where he founded a non-profit World Wide Web Consortium in partnership with MIT and others. The W3C, as it would soon become known, was created to lead the defense of open standards against those corporate and governmental forces which were already demonstrating a desire to monopolize and balkanize the Web. At times, there would be reason to question who was really leading whom; the W3C would, for example, be forced to write into its HTML standard many of the innovations which Netscape had already unilaterally introduced into its industry-leading browser. Yet the organization has undoubtedly played a vital role in keeping the original ideal of the Web from giving way completely to the temptations of filthy lucre. Tim Berners-Lee remains to this day the only director the W3C has ever known.

So, while Marc Andreessen and Jerry Yang and their ilk were becoming the darlings of the business pages, were buying sports cars and attending the most exclusive parties, Tim Berners-Lee was riding a bus to work every day in Boston, just another anonymous commuter in a gray suit. It was fall when he first arrived in his new home, and so, as he says, “the bus ride gave me time to revel in New England’s autumnal colours.” Many over the years have found it hard to believe he wasn’t bitter that his name had become barely a footnote in the reckoning of the business-page pundits who were declaring the Web — correctly, it must be said — the most important development in mass media in their lifetimes. But he himself insists — believably, it must be said — that he was not and is not resentful over the way things played out.

People sometimes ask me whether I am upset that I have not made a lot of money from the Web. In fact, I made some quite conscious decisions about which way to take in life. Those I would not change. What does distress me, though, is how important a question it seems to be for some. This happens mostly in America, not Europe. What is maddening is the terrible notion that a person’s value depends on how important and financially successful they are, and that that is measured in terms of money. This suggests disrespect for the researchers across the globe developing ideas for the next leaps in science and technology. Core in my upbringing was a value system that put monetary gain well in its place, behind things like doing what I really want to do. To use net worth as a criterion by which to judge people is to set our children’s sights on cash rather than on things that will actually make them happy.

It can be occasionally frustrating to think about the things my family could have done with a lot of money. But in general I’m fairly happy to let other people be in the Royal Family role…

Perhaps Tim Berners-Lee is the luckiest of all the people whose names we still recognize from that go-go decade of the 1990s, being the one who succeeded in keeping his humanity most intact by never stepping onto the treadmill of wealth and attention and “disruption” and Forbes rankings. Heaven help those among us who are no longer able to feel the joy of watching nature change her colors around them.

In 1997, Robert H. Reid wrote that “the inevitable time will come when the Web’s dawning years will seem as remote as the pioneering days of film seem today. Today’s best and most lavishly funded websites will then look as naïve and primitive as the earliest silent movies.” Exactly this has indeed come to pass. And yet if we peer beneath the surface of the early Web’s garish aesthetics, most of what we find there is eerily familiar.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the explosion of the Web into the collective commercial and cultural consciousness is just how quickly it occurred. In the three and one quarter years between the initial release of the NCSA Mosaic browser and the Yahoo! IPO, a new digital society sprang into being, seemingly from nothing and nowhere. It brought with it all of the possibilities and problems we still wrestle with today. For example, the folks at Netscape, Yahoo!, and other startups were the first to confront the tension between free speech and hate speech online. (Straining to be fair to everyone, Yahoo! reluctantly decided to classify the Ku Klux Klan under the heading of “White Power” rather than “Fascism,” much less booting it off their site completely.) As we’ve seen, the Internet advertising business emerged from whole cloth during this time, along with all of the privacy concerns raised by its determination to track every single Netizen’s voyages in the name of better ad targeting. (It’s difficult to properly tell the story of this little-loved but enormously profitable branch of business in greater depth because it has always been shrouded in so much deliberate secrecy.) Worries about Web-based pornography and the millions of children and adolescents who were soon viewing it regularly took center stage in the mass media, both illuminating and obscuring a huge range of questions — largely still unanswered today — about what effect this had on their psychology. (“Something has to be done,” said one IBM executive who had been charged with installing computers in classrooms, “or children won’t be given access to the Web.”) And of course the tension between open standards and competitive advantage remains of potentially existential importance to the Web as we know it, even if the browser that threatens to swallow the open Web whole is now Google Chrome instead of Netscape Navigator.

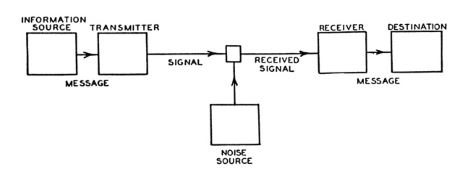

All told, the period from 1993 to 1996 was the very definition of a formative one. And yet, as we’ve seen, the Web — this enormous tree of possibility that seemed to so many to sprout fully formed out of nothing — had roots stretching back centuries. If we have learned anything over the course of the last eleven articles, it has hopefully been that no technology lives in a vacuum. The World Wide Web is nothing more nor less than the latest realization of a dream of instantaneous worldwide communication that coursed through the verse of Aeschylus, that passed through Claude Chappe and Samuel Morse and Cyrus Field and Alexander Graham Bell among so many others. Tellingly, almost all of those people who accessed the Web from their homes during the 1990s did so by dialing into it, using modems attached to ordinary telephone lines — a validation not only of Claude Shannon’s truism that information is information but of all of the efforts that led to such a flexible and sophisticated telephone system in the first place. Like every great invention since at least the end of prehistory, the World Wide Web stands on the shoulders of those which came before it.

Was it all worth it? Did all the bright sparks we’ve met in these articles really succeed in, to borrow one of the more odious clichés to come out of Silicon Valley jargon, “making the world a better place?” Clichés aside, I think it was, and I think they did. For all that the telegraph, the telephone, the Internet, and the World Wide Web have plainly not succeeded in creating the worldwide utopia that was sometimes promised by their most committed evangelists, I think that communication among people and nations is always preferable to the lack of same.

And with that said, it is now time to end this extended detour into the distant past — to end it here, with J.C.R. Licklider’s dream of an Intergalactic Computer Network a reality, and right on the schedule he proposed. But of course what I’ve written in this article isn’t really an end; it’s barely the beginning of what the Web came to mean to the world. As we step back into the flow of things and return to talking about digital culture and interactive entertainment on a more granular, year-by-year basis, the Web will remain an inescapable presence for us, being the place where virtually all digital culture lived after 1995 or so. I look forward to seeing it continue to evolve in real time, and to grappling alongside all of you with the countless Big Questions it will continue to pose for us.

(Sources: the books A Brief History of the Future: The Origins of the Internet by John Naughton, Communication Networks: A Concise Introduction by Jean Walrand and Shyam Parekh, Weaving the Web by Tim Berners-Lee, and Architects of the Web by Robert H. Reid. Online sources include the Pew Research Center’s “World Wide Web Timeline” and Forbes‘s up-to-the-minute billionaires scoreboard.)