To hear him tell the story at any rate, Philippe Ulrich had always been destined to make a computer game out of Dune. On July 21, 1980, he was a starving young musician living in an attic closet in Paris without heat or electricity, having just been dropped by his tiny record label after his first album had stiffed. Threading his way through the tourists packing the Champs-Élysées that scorching summer day, he saw an odd little gadget called a Sinclair ZX80 in the window of an electronics shop. The name of the shop? Dune. His destiny was calling.

But a busy decade still lay between Ulrich and his Dune game. For now, he fell in love at first sight with the first personal computer he had ever seen. His only goal became to scrape together enough money to buy it. Through means fair or foul, he did so, and within a year he had sold his first game, a BASIC implementation of the board game Othello, to Sinclair’s French distributor. He soon partnered up with one Emmanuel Viau, a medical student eager to drop out of university and pursue his real love of programming games. The two pumped out arcade clones and educational drills to raise cash, and officially incorporated their own little software studio, ERE Informatique, on April 28, 1983.

ERE moved up from the ranks of regional developers and arcade-clone-makers to score their first big international hit thanks to one Rémi Herbulot, a financial controller at the automotive supplier Valeo who had learned BASIC to save his company money on accounting software, only to get himself hopelessly hooked on the drug that was programming to personalities like his. Without ever having seen the American Bill Budge’s landmark Pinball Construction Set, Herbulot wrote a program along the same lines: one that let you build your own pinball table from a box of interchangeable parts and then play and share it with your friends. As soon as Herbulot showed his pinball game to Ulrich, he knew that it had far more potential than anything ERE had made so far, and didn’t waste any time hiring the creator and publishing his creation. Upon its release in 1985, Macadam Bumper topped sales charts in both France and Britain, selling almost 100,000 copies in all. It was even picked up by the American publisher Accolade, who released it as Pinball Wizard and saw it get as high as number 5 on the American charts despite the competition from Pinball Construction Set. Just like that, ERE Informatique had made it onto the international stage. For a second act, Rémi Herbulot soon provided the action-adventure Crafton & Xunk — released as Get Dexter! in some places — and it too became a hit across Europe.

Yet none of the free spirits who made up ERE Informatique was much of a businessman — least of all Philippe Ulrich — and the little collective lived constantly on the ragged edge of insolvency. Hoping to secure the funding needed to make more ambitious games to suit the new 16-bit computers entering the market, Ulrich and Viau sold their company to the Lyon-based Infogrames, the largest games publisher in France, in June of 1987. The plan was for ERE to continue making their games, still under their old company name, while Infogrames quietly took care of the accounting and the publishing.

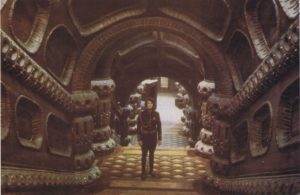

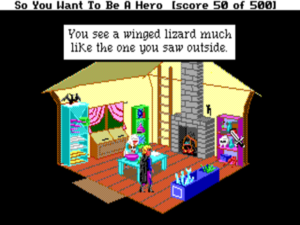

For the past year already, much of ERE’s energy had been absorbed by Captain Blood, a game designed by Ulrich himself and a newer arrival named Didier Bouchon, a student of biology, interior design, film, and painting whom Ulrich liked to describe as his company’s very own “mad scientist.” And, indeed, Captain Blood was something of a Frankenstein’s monster of a game, combining a fractal-based space-flight simulator with a conversation engine that had you talking with the aliens you met in an invented symbolic language. With its Giger-inspired tangles of onscreen organics and technology and a color palette dominated by neon blues and deep purples, it was all extremely strange stuff, looking and playing more like a conceptual-art installation than a videogame. Not least strange was the plot, which cast the player as a programmer who got sucked into an alternate dimension inside his computer, then saw his identity fractured into six by a “hyperspace accident.” Now he must scour the galaxy to find and destroy his clones and reconstitute his full identity. In a major publicity coup, Ulrich managed to convince the famous composer and keyboardist Jean-Michel Jarre to license to ERE the piece of music that became the game’s main theme. Such a collaboration matched perfectly with the company’s public persona, which depicted their games not so much as commercial entertainments as an emerging artistic movement, in line with, as Ulrich liked to say, Impressionism, Dadaism, or surrealism: “Why should it not be the same with software?”

Released for the Atari ST in France just in time for the Christmas of 1987, Captain Blood certainly was, whatever else you could say about it, a bold artistic gambit. The French gaming magazine SVM talked it up if anything even more than Ulrich himself, declaring it “a masterpiece,” “the most beautiful game in the world,” the herald of a new generation of games “where narrative sense and programming talent are at the service of a new art.” This sort of stilted grandiosity — sounding, at least when translated into English, a bit like some of the symbolic dialogs you had with the aliens in Captain Blood — would become one of the international hallmarks of a French gaming culture that was just beginning to break out beyond the country’s borders. Captain Blood became the first poster child for what Philippe Ulrich himself would later dub “the French Touch”: “Our games didn’t have the excellent gameplay of original English-language games, but graphically, their aesthetics were superior.”

It took some time to realize that, underneath its undeniable haunting beauty, Captain Blood wasn’t really much of a game. Playing it meant flying around to random planets, going through the same tedious flight-simulator bits again and again, and then — if you were lucky and the planet you’d arrived at wasn’t entirely empty — having baffling conversations with all too loquacious aliens, never knowing what was just gibberish for the sake of it and what was some sort of vital clue. As Ulrich’s own words above would indicate, he and some other French developers really did seem to believe that making beautiful and conceptually original games like Captain Blood should absolve them from the hard work of testing, tweaking, and balancing them. And perhaps he had a point, at least momentarily. What with owners of slick new 16-bit machines like the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga eager to see them put through their audiovisual paces, gameplay really could fall by the wayside with few obvious consequences. Captain Blood sold more than 100,000 copies worldwide despite its faults. For ERE Informatique, it felt like a validation of their new direction.

So, on June 12, 1988, they announced the formation of a new sub-label for artsy games like Captain Blood in an elaborate “happening” at the storied Maison de la Radio in Paris. The master of ceremonies was none other than Alejandro Jodorowsky, the Chilean filmmaker who had spent $2 million in an abortive attempt to make a Dune movie back in the 1970s. The name of the sub-label, Exxos, was derived from the Greek prefix meaning “outward.” The conceit had it that Exxos was literally the god in the machines at ERE Informatique, the real mastermind of all their games. After Jodorowsky’s introduction, Ulrich stepped up to say his piece:

Ladies and gentlemen, the decision was not easy, but still, we have agreed to reveal to you the secret of our dynamism and creativity, which makes ERE Informatique a success. If there are sensitive people in the room, I ask them to be strong. They have nothing to fear if their vibrations are positive; the telluric forces will save them.

My friends, the inspiration does not fall from the sky, genius is not by chance. The inspiration and genius which designed Macadam Bumper is not the fabulous Rémi Herbulot. The inspiration and genius which led to Captain Blood is not the unquenchable Didier Bouchon nor your servant here.

It is Him! He who has lived hidden in our offices for months. He who comes from outside the Universe. He that we reveal today to the world, because the hour has come. I name Exxos. I ask you to say after me a few magic words to remind Him of His homeland: ata ata hoglo hulu, ata ata hoglo hulu…

A group chant followed, more worthy of an occult ceremony than a business presentation.

Some months later, Rémi Herbulot’s Purple Saturn Day became the first big game to premiere on the Exxos label. It was a sort of avant-garde take on the Epyx Games sports series, if you can imagine such a thing. “O Exxos, you who showed us the path to the global success of Captain Blood, you who inspired those fabulous colorful swirls of spacetime!” prayed Philippe Ulrich before a bemused crowd of ordinary trade-show attendees. “Today it is the turn of Rémi Herbulot and Purple Saturn Day. Exxos, thank you!”

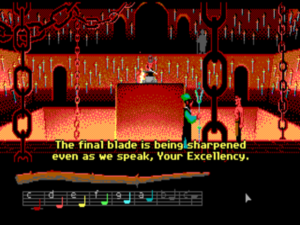

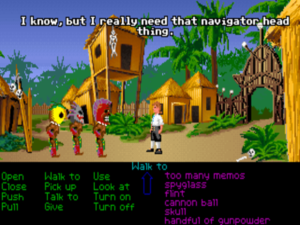

The shtick got old quickly. When ERE promoted the next Exxos game, a poorly designed point-and-click adventure called Kult, by dismembering a life-sized latex alien in the name of their god and distributing the pieces to assembled journalists, you could almost see the collective shrug that followed even in the French gaming press. Neither Purple Saturn Day nor Kult (the latter of which was published under the name of Chamber of the Sci-Mutant Priestess in North America) sold in anything like the numbers of Captain Blood.

Meanwhile Infogrames, ERE’s parent company, had gotten into serious financial trouble through over-expansion and over-investment. After a near-acquisition by the American publisher Epyx fell through at the last minute, Infogrames stopped paying the bills at ERE Informatique. Thanks no doubt to such ruthless cost-cutting, Infogrames would escape by the skin of their teeth, and in time would recover sufficient to become one of the biggest games publishers in the world. ERE, however, was finished. Philippe Ulrich and his little band of followers had been cast adrift along with their god. But never fear; their second act would prove almost as surprising as their first. For Ulrich and company were about to meet Dune.

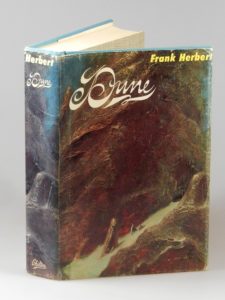

Given the enormous popularity of the novel, one might have expected a Dune computer game long before this point. Yet, thanks to the high-profile but failed Dune film, the rights had been in limbo for the past five years.

As we saw in my previous article, the Dino De Laurentiis Corporation licensed the media rights to Dune — which included game rights — from Frank Herbert in 1982. About six months prior to the film’s release in December of 1984, they made a deal with Parker Brothers — best known as the maker of such evergreen family board games as Monopoly, Clue, and Risk — for a Dune videogame. But said game never materialized; the failure of the film, coupled with a troubled American home-computer marketplace and an all but annihilated post-Great Videogame Crash console marketplace, apparently made them think better of the idea. The Dino De Laurentiis Corporation went bankrupt in 1985, and Frank Herbert died the following year. Despite the inevitable flurry of litigation which followed these events, no one seemed to be quite sure for a long time just where the game rights now resided. The person who would at last break this logjam at decade’s end was a dapper 47-year-old Briton named Martin Alper.

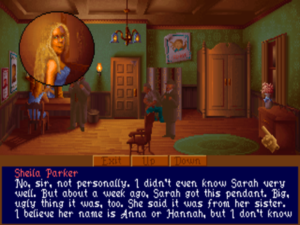

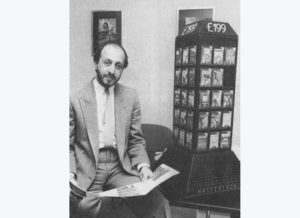

Martin Alper with a display rack of cheap games. These were to be found in all sorts of unlikely places in Britain, from corner shops to booksellers, during Mastertronic’s heyday.

Alper had gotten his start in software in 1983, when, already an established businessman and entrepreneur, he had invested in a tape-duplication facility. At this time, British computer games were distributed almost exclusively on cassette tapes. “I asked the guy how much it cost to duplicate a tape,” Alper later remembered. “He said about 30p. Then I asked him how much they sold the games for. About eight or nine pounds. I couldn’t understand the massive difference.” In his confusion he detected the scent of Opportunity. The result would be Mastertronic, the most internationally successful budget label of the 1980s.

Alper and two others launched Mastertronic in April of 1984 with several games priced at £1.99, about half the lowest price point typical in Britain at the time. The figure was no accident: a survey had revealed that £2 was the average amount of weekly pocket money given to boys of twelve years old or so by British parents. Thus, while the typical kid might have to save up for several weeks to buy a game from the competition, he could buy a new one every single weekend from Mastertronic if he was sufficiently dedicated. And dedicated the kids of Britain proved to be, to the tune of 130,000 Mastertronic games shipped in the first month.

The established powers in the British games industry, however, were less enthusiastic. Claiming that selling games at such prices would set everyone on the road to ruin, distributors flatly refused to handle Mastertronic’s products. Unfazed, Alper and his partners simply went around them, setting up their own distribution pipeline with the likes of the bookstore chain W.H. Smith and even supermarkets and convenience stores, who were advised to place the freestanding pillars of Mastertronic games, with “£1.99!” emblazoned in big digits across the top, right where parents and children passed by on their way to the cash register with their groceries. “The problem with the conventional retail outlets,” said Alper, “is [that] they don’t encourage the impulse purchase. Supermarkets are much better at that.”

Mastertronic’s simple action games weren’t great, but for the most part they weren’t as horrible as the rest of the industry liked to claim either. If they lacked the staying power of many of their higher-priced rivals, that could be rationalized away in light of the fact that a kid could buy a new one every week or two. And Alper proved hugely talented at tempting his target demographic in all sorts of ways that didn’t depend directly on the quality of the games themselves. One of Mastertronic’s biggest early hits was a knock-off of Michael Jackson’s extended “Thriller” video, renamed to Chiller. (Predictably enough, they were hauled into court by Jackson’s management company and wound up having to pay a settlement, but they still came out well-ahead financially.) Another game, Clumsy Colin Action Biker, starred the mascot from a popular brand of crisps, and was advertised right on the packages of said junk food. (“They showed us how they were made. It’s revolting. You know those little plastic chips you get in packing materials? They’re exactly the same, with added flavoring.”)

It was all pretty lowbrow stuff — about as far as you could get from the high-toned pretensions of ERE Informatique across the English Channel — but Mastertronic’s games-as-commodies business model proved very successful. Within eighteen months of their launch, Mastertronic alone owned 20 percent of the British computer-games market, was expanding aggressively across the rest of Europe, and had become the first British software house to launch a successful line in the United States. In fact, Martin Alper had already moved to California, the better to steer operations there.

But Mastertronic’s glory days of huge profits off cheap games were brief-lived. Just like Infogrames in France, they tried to do too much too soon. Losing sight of their core competencies, they funded a line of coin-operated arcade games that went nowhere and acquired the prestigious but troubled British/Australian publisher Melbourne House for way too much money. At the same time, the army of lone-wolf bedroom coders who provided their games proved ill-equipped to take full advantage of the newer 16-bit machines that began to capture many gamers’ hearts and wallets as the 1980s wore on. Already by 1987, Mastertronic’s bottom line had turned from black to red.

Meanwhile Virgin Games, one of the smaller subsidiaries of Richard Branson’s globe-spanning media empire, had been quietly releasing games in Britain since 1982. Now, though, Branson was eager to get into the games market in a more concentrated way. Mastertronic, possessed of excellent worldwide distribution and proven marketing savvy despite their current financial difficulties, seemed a great way to do that. In early 1988, Virgin bought Mastertronic.

Initially, the new subsidiary took the name of Virgin Mastertronic and simply continued on with business as usual. But as Martin Alper looked upon a changing industry, he saw those more powerful 16-bit platforms continuing to take over from the simple 8-bit machines that had fueled Mastertronic’s success, and he saw older demographics with more disposable income beginning to take an interest in more sophisticated, upmarket computer games. In short, he felt that he had already hit a ceiling with his cheap little games; what had been so right for 1984 was no longer such a great fit for 1988. And so Alper, a man of enormous charisma and energy, maneuvered himself into the leading role at Virgin Games proper, overseeing its worldwide operations from California, the entertainment capital of the world. After having fallen into exactly the decline Alper had foreseen, Virgin Mastertronic would be sold off in 1991 to the Japanese console maker Sega, with whom they had a longstanding distribution agreement.

Alper loved Dune, connecting with its mythical — mystical? — qualities on a deep-seated level: “It presents a parallel with Christianity or Judaism, including the idea of the messiah who comes to save a strange planet. Dune begs questions about other civilizations that could exist: will they have the same beliefs, worship the same supernatural beings?” He had always dreamed of publishing a Dune computer game, but had known it just wasn’t practical on a Mastertronic budget. Now, though, with the more prestigious name and deeper pockets of Virgin behind him, he started pursuing the license in earnest. Beginning in 1988, he worked through a long, fraught process of first identifying the proper holder of the media rights — as far as could be determined from all of the previous litigation and bankruptcies, they seemed to have reverted to Universal Pictures, the distributor of the film — and then of prying them away for Virgin. Alper saw a Dune game as announcing Virgin’s — and his own — arrival on the scene as a major industry player in an artistic as well as commercial sense, making games far removed from the budgetware of the Mastertronic years.

Even as Alper was trying to secure the Dune rights, Philippe Ulrich and his friends were trying to free themselves from their entanglements with Infogrames and continue making games elsewhere. They found a welcome supporter in Jean-Martial Lefranc, the head of Virgin Loisirs, Virgin Games’s French arm. Manifesting a touch of Gallic pride, he wanted to set up a homegrown studio, made up of French developers creating ambitious and innovative games which would be distributed all over the world under the Virgin label. And certainly no one could accuse Ulrich and friends of lacking either ambition or a spirit of innovation. Lefranc helped to negotiate a concrete exit agreement between the former ERE Informatique and Infogrames, and thereafter signed them up to become the basis of a new Virgin Loisirs subsidiary.

Ulrich and company named their new studio Cryo Interactive, a play on cryogenic chambers and the computer-assisted dreams people would presumably have in them in the future. They announced their existence with all the grandiosity the world had come to expect from this bunch, saying that their purpose would be to “open the way to the next generation of software designers, artists, programmers, and so on,” who would “create expanding horizons for our imagination in tomorrow’s fascinating technology world.” “Infinite travel, magic, beauty, technology, adventure, and mystery” were in the offing.

In August of 1989, Rémi Herbulot flew to California to have a more prosaic conversation with Martin Alper about potential Cryo projects that might be suitable for the international market. Alper told him then that he was trying to secure the rights to make a Dune game, a project for which he saw Cryo as the perfect development team, without elaborating as to why. “But,” he said, “there’s seems to be little chance of actually getting the rights.”

Herbulot wasn’t sure what to make of the whole exchange, but when he told his colleagues about it back in Paris, Ulrich, who loved the novel unconditionally, was convinced that the project had been ordained by fate. Not only had he bought his first computer in a shop called Dune, but the hotel in Las Vegas where they had all stayed during the last Winter Consumer Electronics Show had had the same name. And then there was his friendship with Alejandro Jodorowsky, the would-be Dune film director of yore. What another might have seen as a series of tangential coincidences, Ulrich saw as the mysterious workings of destiny. It was “obvious,” he said, that Cryo would end up making Dune into a computer game — and, indeed, he was proven correct. Three weeks after Herbulot’s return from California, Ulrich got a call at home from Jean-Martial Lefranc. Martin Alper had managed to secure the Dune license after all, said Virgin Loisir’s chief executive, and he wanted Cryo to start thinking immediately about what kind of game they could make out of it. Ulrich remembers running out of his apartment building and doing several laps around the block, feeling like he was levitating.

But his ecstasy would be short lived. Virgin assigned as Dune‘s producer David Bishop, a veteran British games journalist, designer, and executive. The language barrier and the distance separating London from Paris were just the beginning of the difficulties that ensued. In the eyes of his French charges, Bishop seemed to view himself as Dune‘s appointed designer, Cryo as the mere technical team assigned to implement his vision. Given the artistic aspirations of people like Philippe Urlich and Rémi Herbulot, who so forthrightly described themselves as the vanguard of nothing less than a new artistic movement, this was bound to cause problems. Meanwhile Bishop, for his part, was convinced that Cryo was being deliberately obtuse and oh so inscrutably Gallic just to mess with him. The cross-Channel working relationship started out strained and just kept getting more so.

Following what was, for better or for worse, becoming an accepted industry practice, Virgin told Cryo that they had to storyboard the game on paper and get that approved before they could even begin to implement anything on a computer. Cryo worked this way for months on end, abandoning their computers for pencil and paper.

Adapting a story as complex as that of Dune to another medium must be, as David Lynch among others had already learned, a daunting endeavor under any circumstances. “We reread the book several times, got hold of everything we could find on the subject, and watched the movie over and over again,” says Philippe Ulrich. “Whenever we came across somebody who had read the book, we asked them what had impressed them most and what their strongest memories were.” The centerpiece of the book and the movie, the struggle for control of Arrakis between House Atreides and House Harkonnen, must obviously be the centerpiece of the game as well. Yet Cryo didn’t want to lose all of the other textures of the story. How could they best capture the spirit of Dune? To boil it all down to yet another game of military strategy in an industry already flooded with such things didn’t seem right, but neither did a point-and-click adventure game. After much struggle, they decided to do both — to combine a strategic view of the battle for Arrakis with the embodied, first-person role of Paul Atreides.

David Bishop hated it. All of it. “The interface is too complex,” he said. “A mix of adventure and strategy is not desirable.” Others in Virgin’s British and American offices also piled on. Cryo’s design lacked “unity,” they said; it would require “fifty disks” to hold it; it had “too many cinematic sequences, at the risk of boring the player”; the time required to develop it would “exceed the average lifespan of a programmer.” One particular question was raised endlessly, if understandably in light of Cryo’s history: would this be a game that mainstream American gamers would want to play, or would it be all, well, French? And yes, it was a valid enough concern on the face of it. But equally valid was the counterpoint raised by Ulrich: if you didn’t want a French Dune, why did you hire arguably the most French of all French studios to make it? Or did Bishop feel that that decision had been a mistake? Certainly Cryo had long since begun to suspect that his real goal was to kill the project by any means necessary.

Matters came to a head in the summer of 1990. In what may very well still stand as an industry record, Dune had now been officially “in production” for almost a year without a single line of code getting written. Virgin invited the whole of Cryo to join them at their offices in London to try to hash the whole thing out. The meeting was marked by bursts of bickering over trivialities, interspersed with long, sullen silences. At last, Philippe Ulrich stood up to make a final impassioned speech. He said that Cryo was trying their level best to make a game that evoked all of the major themes of a book they loved (never mind for the moment that the license Virgin had acquired could more accurately be described as a license to the movie). The transformation of boy to messiah was in there; the all-importance of the spice was in there; even the ecological themes were in there. David Bishop just snorted in response; Virgin wanted a commercial computer game that was fun to play, he groused, not a work of fine literary art. Nothing got resolved.

Or perhaps in a way it did. On September 19, 1990, Cryo got a fax from London: “We do not believe that the Dune proposal is strong enough to publish under the Virgin Games label. Consequently, we do not wish that more work be undertaken on this title.”

And then, at this fraught juncture, a rather extraordinary thing happened. Ulrich went directly to Jean-Martial Lefranc of Virgin Loisirs to plead his case one final time, whereupon Lefranc told him to just go ahead and make his Dune his way — to forget about storyboards and David Bishop and all the rest of it. Virgin Loisirs was doing pretty well at the moment; he’d find some money in some hidden corner of his budget to keep the lights on at Cryo. If they made the Dune game a great one, he was sure he could smooth it all over with his superiors after the fact, when he had a fait accompli in the form of an amazing game that just had to be published already in his hands. And so Ulrich took a second lap or two around the block and then buckled down to work.

For some six months, Cryo beavered away at their Dune in secrecy. Then, suddenly, the jig was up. Lefranc — who, as his actions in relation to Dune would indicate, didn’t have an overly high opinion of Virgin Games’s international management — left to join the movie-making arm of the Virgin empire. His replacement, Christian Brécheteau, was a complete unknown quantity for Cryo. At about the same time, a routine global audit of the empire’s books sent word back to London about a significant sum being paid to Cryo every month for reasons that were obscure at best. Brécheteau called Ulrich: “Take the first plane to London and make your own case. I can’t do anything for you.”

As it happened, Martin Alper was in London at that time. If Ulrich hoped for a sympathetic reception from that quarter, however, he was disappointed. After pointedly leaving him to cool his heels in a barren waiting room most of the day, Alper and other executives, including Cryo’s arch-nemesis David Bishop, invited Ulrich in. The mood was decidedly chilly as he set up his presentation. “This is not a game!” scoffed Alper almost immediately, as soon as he saw the first, heavily scripted scenes. Yet as Ulrich demonstrated further he could sense the mood — even the mood of Bishop — slowly changing to one of grudging interest. Alper even pronounced some of what he saw “remarkable.”

Ulrich was ushered out of the room while the jury considered his fate. When he was called back in, Alper pronounced their judgment: “You have five weeks to send me something more polished. If that doesn’t please me, I never want to hear about it again, and you can consider yourself fired.” A more formal statement of his position was faxed to Paris the next day:

Our opinion of the game has not changed. The graphics and aesthetic presentation are impressive, but the overall design is still too confusing, especially if one takes into account the tastes of the American public. We are willing to support your work until July 15 [1991], by which date we expect to receive a playable version of the game in England and the United States. If the earlier concerns expressed by David Bishop prove unfounded, we will be happy to support your efforts to realize the finished game. However, we wish to point out that it will not under any circumstances be possible to transfer the Dune license to another publisher, and that no game of Frank Herbert’s novel will be published without our consent. [1]Virgin’s concern here was likely related to the fact that they had technically purchased the rights to the Dune movie. The question of whether separate rights to the novel existed and could be licensed had never really been resolved. They wanted to head off the nightmare scenario of Cryo/Virgin Loisirs truly going rogue by acquiring the novel rights and releasing the game under that license through another publisher.

Cryo bit their tongues and made the changes Virgin requested — changes designed to make the game more streamlined, more understandable, and more playable. On July 15, they packaged up what they had and sent it off. Three days later, they got a call from a junior executive in Virgin’s California office. His tone was completely different from that of the fax of five and a half weeks earlier: “What you have done is fantastic. Productivity has collapsed around here because people are all playing your game!”

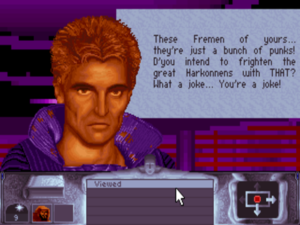

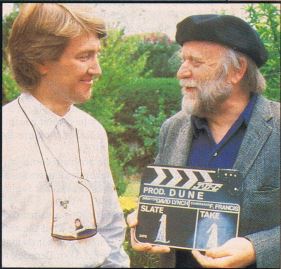

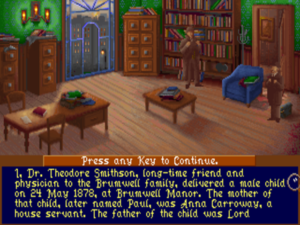

Cryo originally planned to use this picture of Sting in their Dune game, but the rock star refused permission to use his likeness.

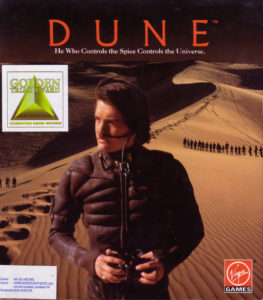

Work continued on the game for another nine months or so. Relations between Cryo and Virgin remained strained at times over that period, but cancellation was never again on the cards. At Virgin’s insistence, Cryo spent considerable time making the game look more like the movie, rather than their possibly idiosyncratic image of the book. Most of the characters, with the exception of only a few whose actors refused permission to have their likenesses reproduced — Sting and Patrick Stewart were among them — were redrawn to match the film. The media-savvy Martin Alper was well aware that Kyle MacLachlan, the star of the film, was currently starring in David Lynch’s much-talked-about television series Twin Peaks. He made sure that MacLachlan graced the front of the box as Paul Atriedes.

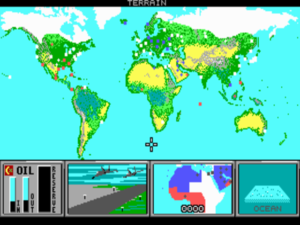

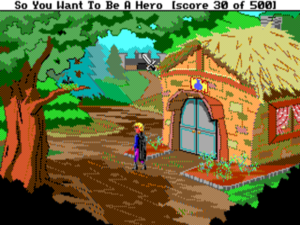

Cryo’s Dune finally shipped worldwide in May of 1992, to positive reviews and healthy sales; one report claims that it sold 20,000 copies in its first week in the United States alone, a very impressive performance for the time. It did if anything even better in Europe; Cryo had been smart enough to develop and release it simultaneously for MS-DOS, the overwhelmingly dominant computer-game platform in North America, and for the Commodore Amiga, the almost-as-popular computer-gaming platform of choice in much of Europe. The game was successful enough that Virgin funded expanded MS-DOS and Sega Genesis CD-based versions, which appeared in 1993, complete with voice acting and additional animation sequences.

And what can we say about Cryo’s Dune today? I will admit that I didn’t have high hopes coming in. As must be all too clear by now, I’m not generally a fan of this so-called French Touch in games. While I love beauty as much as the next person and love to be moved by games, I do insist that a game work first and foremost as a game. This isn’t a standard that Philippe Ulrich’s teams tended to meet very often, before or after they made Dune. The combination of Ulrich’s love of weirdness with the famously weird filmmaker David Lynch would seem a toxic brew indeed, one that could only result in a profoundly awful game. Inscrutability can work at times in the non-interactive medium of movies; in games, where the player needs to have some idea what’s expected from her, not so much.

But, rather amazingly, Cryo’s Dune defies any knee-jerk prejudices that might be engendered by knowledge of Philippe Ulrich’s earlier or later output. While it’s every bit as unique a design concept as you might expect given its place of origin, in this case the concept works. For all that they spent the better part of three years at one another’s throats more often than not, Dune nevertheless wound up being a true meeting in the middle between the passionate digital artistes of Cryo and the more practical craftsmen in Virgin’s Anglosphere offices. For once, an exemplar of the French Touch has a depth worthy of its striking surface. Dune plays like a dispatch from an alternate reality in which Cryo cared as much about making good games in a design sense as they did about making beautiful and meaningful ones in an aesthetic and thematic sense — thus proving, should anyone have doubted it, that these things need not be mutually exclusive.

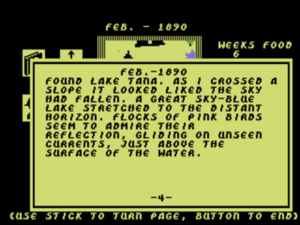

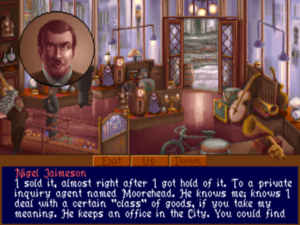

The game leads you by the nose a bit at the beginning, but it later opens up. The early stages function very well as a tutorial for the strategy game. Thanks to this fact and the simple, intuitive interface, the Dune player has little need for the manual.

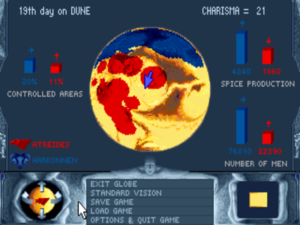

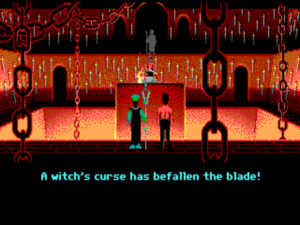

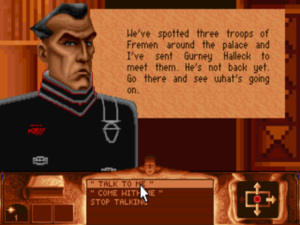

You play the game of Dune as Paul Atreides, just arrived on Arrakis with his father and mother and the rest of House Atreides. From his embodied perspective, you fly around the planet in your ornithopter, recruiting the various Fremen clans to your cause, then directing them to mine the precious spice, to train in military maneuvers, to spy on House Harkonnen, and eventually to go to war against them. As you’re doing so, another form of plot engine is also ticking along, unfolding the experiences which transform the boy Paul Atreides physically and spiritually into his new planet’s messiah. This “adventurey” side of the game is extremely assertive at first, to the point of leading you by the nose through the strategy side: go here and do this; now go there and do that. In time, however, it eases up and your goals become more abstract, giving much more scope for you to manage the war your way.

The fusion isn’t always perfect; it is possible to break the adventure side of the game if you obstinately pursue your own agenda in the strategy side. But it’s certainly one of the most interesting and successful hybrid designs I’ve ever seen. As the character you play is transformed by his experiences, so is the strategy game you’re playing; as Paul’s psychic powers grow, you no longer have to hop around the planet as much in your physical form, but can communicate with your followers over long distances using extra-sensory perception. Eventually your powers will expand enough to let you ride the fearsome sandworms into the final series of battles against the Harkonnen.

Cryo’s Dune provides other ludic adaptations from non-interactive media with a worthy benchmark to strive for; it doesn’t always fuss overly much about the details of its source material, but it really does do a superb job of capturing its spirit. As an impassioned Philippe Ulrich noted at that pivotal meeting in London, there’s no theme in the book that isn’t echoed, however faintly, in the game. Even the ecological element of the book that made it such a favorite of the environmental movement is remembered, as you reclaim mined-out desert lands to begin a “greening” of Arrakis later in the game. Ditto that wind of utter alienness that blows through the book and, now, the game. This game looks and feels and, perhaps most of all, sounds like no other; its synthesized soundtrack has passed into gaming legend as one of the very best of its breed, so good that Cryo actually released it as a standalone audio CD.

An in-game encyclopedia is available for newcomers, but in truth it’s hardly needed. The game conveys everything you really need to know almost subliminally as you play.

The game manages to be so evocative of its source material while remaining as enjoyable for those who haven’t read the novel or seen the film as those who have. It does a great job of getting newcomers up to speed, even as its dynamic, emergent strategy element ensures that it never becomes a dull exercise in walking through a plot those who have read the book already know. Its interface is an intuitive breeze, and the difficulty as well is perfectly pitched for what the game wants to be, being difficult enough to keep you on your toes but reasonable enough that you have a good chance of winning on your first try; after all, who wants to play through a story-oriented game like this twice? I love to see innovative approaches to gameplay that defy the strict boundaries of genre, and love it even more when said approaches work as well as they do here. This game still has plenty to teach the designers of today.

Sadly, though, Cryo’s Dune, despite its considerable commercial success, has gone down in history as something of a curiosity rather than a harbinger of design trends to come, a one-off that had little influence on the games that came later — not even the later games that came out of Cryo, which quite uniformly failed to approach the design standard set here. Cryo would survive for the balance of the 1990s, churning out what veteran games journalist John Walker calls, in his succinct and hilarous summing up of their legacy, “always awful but ever so sincere productions.” They would become known for, as Walker puts it, “deadpan adventure games set in wholly ludicrous reinterpretations of out-of-copyright works of literature, in which nothing made sense, and all puzzles were unfathomable guesswork.” The biggest mystery surrounding them is just how the hell they managed to stay in business for a full decade. Just who was buying all these terrible games that all of the magazines ripped to shreds and no one you talked to would ever admit to even playing, much less enjoying?

Nor did anyone else emerge to take up the torch of games that were designed to match the themes, plots, and settings of their fictions rather than to slot into some arbitrary box of ludic genre. Instead, the lines of genre would only continue to harden as time went on. Interesting hybrids like Cryo’s Dune became a more and more difficult sell to publishers, for dismaying if understandable reasons: said publishers were continuing to look on as their customers segregated themselves into discrete pools, each of which only played a certain kind of game to the exclusion of all others. And so Cryo’s Dune passed into history, just one more briefly popular, now obscure gem ripe for rediscovery…

But wait, you might be saying: I claimed at the end of the first article in this series that Dune left a “profound mark” on gaming. Well, as it happens, that is true of Dune in general — but not true of this particular Dune game. Those months during which Cryo and Virgin Loisirs took their Dune underground — months during which the rest of Virgin Games had no idea what their French arm was doing — had yet more ramifications than those I’ve already described. For, during the time when he believed the Cryo Dune to be dead, Martin Alper launched a new project to make another, very different sort of Dune game, using developers much closer to his home base in California. This other Dune would be far less inspiring than Cryo’s as an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel or even of David Lynch’s film, but its influence on the world of gaming in general would be far more pronounced.

(Sources: the book La Saga des Jeux Vidéo by Daniel Ichbiah; Home Computer of June 1984; CU Amiga of July 1991 and June 1992; Amiga Format of March 1990; Computer and Video Games of August 1985, November 1985, and April 1986; New Computer Express of February 3 1990; Amstrad Action of March 1986 and April 1986; Retro Gamer 90; The One of May 1991 and June 1992; Game Players PC Entertainment Vol. 5 No. 5; PC Review of June 1992; Aktueller Software Markt of August 1994; Home Computing Weekly of May 8 1984, July 17 1984, and September 18 1984; Popular Computing Weekly of July 19 1984; Sinclair User of January 1986; The Games Machine of October 1987; Your Computer of January 1986. Online sources include “I Kind of Miss Dreadful Adventure Developer Cryo” by John Walker on Rock Paper Shotgun and “How ‘French Touch’ Gave Early Videogames Art, Brains” by Chris Baker on Wired. Note that some of the direct quotations in this article are translated into English from the French.

Feel free to download Cryo Interactive’s Dune from right here, packaged so as to make it as easy as possible to get running using your platform’s version of DOSBox.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Virgin’s concern here was likely related to the fact that they had technically purchased the rights to the Dune movie. The question of whether separate rights to the novel existed and could be licensed had never really been resolved. They wanted to head off the nightmare scenario of Cryo/Virgin Loisirs truly going rogue by acquiring the novel rights and releasing the game under that license through another publisher. |

|---|