Mystery stories have been a staple of adventure gaming since 1978’s Mystery Mansion. That’s little surprise; no other form of traditional static literature so obviously sees itself as a form of game between reader and writer, and thus is so obviously amenable to adaptation into other ludic forms. Said adaptations existed well before the computer age, in such forms as the Baffle Books of the 1920s, the Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers of the 1930s, and the perennial board game Cluedo (Clue in North America) of 1949.

The early computerized mystery games had the superficial trappings of classic mystery literature but little of the substance. Games like Mystery Mansion and Mystery House were essentially standard Adventure-style treasure hunts, full of mazes and static puzzles, that happened to play out on the stage set of a mystery story. It really wasn’t possible to implement much else with, say, On-Line’s primitive Hi-Res Adventure engine.

That, of course, is why Infocom’s Deadline came as such a revelation. Unlike virtually everyone else making adventure games as of 1982, Infocom had the tools to do a mystery right, to capture the spirit and substance of classic mystery stories in addition to the window dressing. With such a proof of concept to examine (and one which proved to be a major hit at that), combined with a recent uptick in interest in the mystery genre within ludic culture in general following the republication of the old Dennis Wheatley dossiers and an elaborate new board game called Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective, other developers started diving into mysteries with similar earnestness. Some of them worked in the text-adventure form, but others branched out into other paradigms. For instance, Spinnaker’s two child-oriented Snooper Troops games and CBS Software’s two adult-oriented Mystery Master games replaced parsers and a single complex story with a more casual form of crime solving. Each contains a series of shorter cases to solve by traveling around a graphical city map, ferreting out clues at each location using a menu-driven interface. A top rating is achieved by solving the crime quickly, using a minimum of clues.

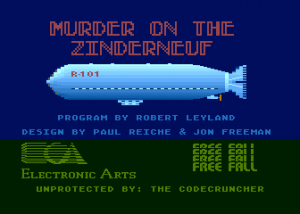

And then there was the game that would become known mostly as that other Free Fall game after the huge success of Archon: Murder on the Zinderneuf. It’s that most interesting anomaly that pops up more than you might expect, an adventure game designed by someone who didn’t much like adventure games.

Jon Freeman laid out his objections to traditional adventure games in an article in the December 1980 issue of Byte, contrasting the form and its limitations with those of the CRPG form he was then working with in crafting Automated Simulations’s DunjonQuest games. An adventure game, he says, is so static that it’s hardly a game at all. It’s “really a puzzle that, once solved, is without further interest.” The former part of this claim became increasingly less true as more dynamic, responsive game worlds like that of Deadline were developed, but the latter part… well, it’s hard to deny that point. The real question is to what extent this bothers you. One remedy to this fundamental failing is perhaps to create longer, deeper works that take as long to play once as it might take you to exhaust the interest of another type of game over many, many plays. Another, of course, is to simply say so what, to note that no one ever criticizes other forms of art, like books, for not being infinitely re-readable (not that Shakespeare doesn’t come close). But still, a re-playable adventure (or for that matter re-readable book) would, all else being held equal, be superior to a non-re-playable version of the same game. Freeman, who still lists Cluedo amongst his favorite games of all time, recycled that game’s concept on the computer, but fleshed out the suspects, the setting, the randomly generated stories behind the murders themselves, to make something more in line with the expectations of adventure gamers.

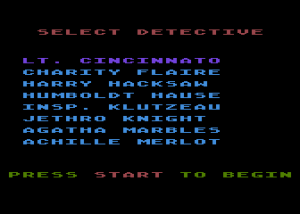

The mystery may change, but the setting and the actors, the raw materials of these little computer-generated dramas, must inevitably remain the same. Luckily, they’re pretty inspired. The game takes place in 1936, the heyday of the rigid airship, surely one of the most romantic and just plain cool methods of travel ever invented. On a trans-Atlantic voyage aboard the fictional German airship Zinderneuf, a murder has been committed. Which of the sixteen passengers was killed, and which did the killing, and why… these are the elements that are generated anew each time. As a whole genre of pulp-action tabletop RPGs have taught us, the 1930s are a wonderful period for fans of intrigue and derring-do, and Zinderneuf uses that well. Freeman and Reiche work in a lot of the era’s touchstones: old Hollywood, action serials, the Berlin Olympics, the Spanish Civil War, the mob, Amelia Earhart, spiritualism, adventurous archaeologists (Raiders of the Lost Ark was still huge while they worked on the game), and of course Communists and Nazis. It’s an effervescent, pulpy version of history. (That said, our libertarian friend Freeman just can’t restrain himself from taking a political shot at Franklin Delano Roosevelt that strikes a weird sourpuss note amongst all the fun: “Roosevelt was still offering his own version of ‘bread and circuses’ as he ‘guided’ the United States through an unprecedented four terms of depression and war.”) The Zinderneuf itself, meanwhile, proves perfect for a Murder on the Orient Express-style whodunnit. Playing as one of eight detectives drawn from literature or television — including homages to Mike Hammer, Miss Marple, Columbo, and the inevitable Sherlock Holmes among others — you have twelve hours to solve the case before the Zinderneuf touches down in New York and the suspects all scatter to the winds.

Those twelve hours translate to just 36 minutes of game time — yes, this is a real-time game. The idea here was to replace a 40-hour adventure game with a half-hour game that “can be replayed 100 times.” Also replaced are the text and parser, with a top-down graphical display and an entirely joystick-driven interface.

Each game begins by telling you who has been murdered from among the cast of characters, each of whom receives a capsule bio in the manual. And then, as Holmes would say (and the manual happily quotes), the game is afoot. You collect evidence in two ways. First, you can search the cabins of the victim and any of the other passengers to see what connections you can discover.

In the case above, I now know that the murderer of Oswald Stonemann is most likely someone with black hair; the victim is always assumed to have been killed in his cabin. This immediately narrows the suspect list down to five. A logical next step may be to search the cabins of those five suspects, to see what further connections I can turn up. Eventually, however, I will want to start questioning suspects. I can choose the approach I take to each. Various approaches are more or less favorable to different combinations of detective and suspect, something that must be deduced with play. If I choose wisely, perhaps I get a clue.

When I believe I have determined opportunity and motive (the game is oddly uninterested in the actual means of murder), I can accuse someone. A false accusation, or one based on insufficient evidence, doesn’t end the game, but does greatly affect your “detective rating” at the end, and prevents you from using that suspect as a source of information for the rest of the game. If you haven’t accused anyone by the time twelve hours (i.e., 36 minutes) have passed, you get one last chance to make an accusation, at some cost to your detective rating, before the game reveals the murderer for you.

There’s much that’s very impressive here. The randomly-generated cases go far beyond the likes of Colonel Mustard in the drawing room with the pistol. Most of the cases don’t even involve that most reliable standby of the mystery writer, love triangles. One time I discovered that Phillip Wollcraft, the archaeologist, had killed the young Natalia Berenski because he was in thrall to certain nameless be-tentacled somethings and needed a handy virgin to sacrifice. (Yes, even the H.P. Lovecraft mythos makes an appearance in this giddy pastiche of a setting, marking what may just be its first appearance in a computer game.) Another time I discovered that the beautiful pilot and all-around adventuress Stephie Hart-Winston had killed the Reverend Jeremiah Folmuth after learning he had in turn killed her beloved brother in a hit-and-run car accident years before. Other cases involve espionage (a natural given the time period), blackmail, even vampires. Most manage to tie the crime back to the period and setting and the specific persona of the characters involved with impressive grace.

But for all that, and despite its superficially easy joystick-driven interface and bright and friendly onscreen graphics that actually look much nicer (at least on the Atari) than those of Archon, Zinderneuf doesn’t quite work for me. Part of the problem derives from all of that rich background information existing only in the manual, not on the screen. The first half-dozen times you play you’re frantically flipping through the pages trying to figure out just who is who as the clock steadily ticks down, an awkward experience a million miles away from Trip Hawkins’s ethos for a new, more casual sort of consumer software. By the time you get over that hump, some of the seams in the narrative generator are already starting to show. You learn what combinations of clues generally lead where, and start to see the same motives repeat themselves. For all the game’s narrative flexibility, there are just eight master stories into which all of the other elements must be slotted. The shock of Wollcraft doing the deed diminishes considerably after you see the same story repeat itself again, with only the name of his victim changed. All of these limitations are of course easily understandable in light of the 48 K of memory the game has at its disposal. Still, things started feeling very shopworn for me long before Freeman’s ideal of a hundred plays.

I also found other elements of the design problematic. When you get down to it, there just isn’t that much to really do, and what there is is often more frustrating than it needs to be. Searching a cabin requires wandering about it trying to cover every square inch until the game beeps to inform you that you discovered a clue — or did not. And talking to suspects can be just as off-putting. Most will only answer a question or two before wandering off again; you then aren’t allowed to speak to them again without speaking to someone else first. Thus the game quickly devolves into a lot of sifting through denials and non-committals, struggling to figure out the right approach to use, while only being able to field one or two questions to your star witness (or suspect) at a time. The memory limitations so strangle the dialog that it’s impossible to pick up clues, as you might in a real conversation, about whether or why your current interrogation approach is failing, or which one might better suit. Murder on the Zinderneuf is fascinating and groundbreaking as a concept, but ultimately a game should be fun in addition to any other virtues it might possess, and here I’m just not sure how well it succeeds. Reading the manual with its cast of exaggerated characters was for me almost more entertaining than actually playing.

Zinderneuf‘s ideal of a narrative that is new every time is neat, and certainly interesting for someone like me to write about as the road almost entirely not taken in adventure games. But are there perhaps good reasons for it to be the road not taken? Maybe for someone primarily interested in games as experiential fictions a 40-hour story, crafted by a person, is more satisfying than 100 30-minute stories generated by the computer. At risk of making Freeman a straw man for my argument, it’s tempting to think again about the flaws that he believed he saw in existing adventures. I believe that designers who see games as rules systems to be carefully crafted and tweaked are often put off by adventure games, which are ultimately all about the fictional context, the lived experience of playing the protagonist in a story. Perhaps having the system itself generate the story could be seen, consciously or unconsciously, as a way to fix this perceived imbalance, to return the art of game design (as opposed to fiction-authoring) to the center of the equation. Yes, Murder on the Zinderneuf‘s narrative generator is clever, but it’s not as clever as, say, Marc Blank, the author of Deadline — and arguably not clever enough to sustain a genre whose appeal is so deeply rooted in its fiction. Zinderneuf is more interesting as a system than as a playable story, in a genre whose appeal is so rooted in story. That, anyway, is how this story lover sees it. Which isn’t to discount Zinderneuf‘s verve in trying something so new. We need our flawed experiments just as much as we do our masterpieces, for they push boundaries and give grist for future designers’ mill. (In that spirit, check out Christopher Huang’s An Act of Murder sometime, which does in text much of what Zinderneuf does in graphics, with results I find more satisfying.)

For several years after 1983, their landmark year of Archon and Murder on the Zinderneuf, Free Fall remained a prominent presence in the growing games industry. In 1984 they released Adept, a sequel to Archon that didn’t quite attract the same love or sales, but was nonetheless a solid success. Soon after they were given an early prototype of the Amiga, thanks to an arrangement Trip Hawkins, a great booster of that machine, worked out with Commodore. Their superb port of Archon became one of the first games available for the Amiga, and they followed it shortly after with a port of Adept of similar quality. Many players still consider these the definitive versions of both games.

Freeman also became a prominent voice in the emerging field of game-design theory, which was separating itself at last by the mid-1980s from the very different art of game programming. He, a defiant non-programmer who had written three books and numerous articles about the art of board-game design before founding Free Fall, was ideally suited to push that process along. Like the last designer I profiled, Dan Bunten, Freeman was given a soapbox of sorts via a column (“The Name of the Game”) in Computer Gaming World. Its ostensible purpose was to tackle tough, controversial subjects head-on. Yet there’s a thin line between delivering hard-hitting, unvarnished reality as one sees it and, well, just kind of sounding like a jerk, and I’m not sure Freeman always stays on the right side of it. His hilarious rant about the Commodore 64 proves that, whatever else he may be, he is no Nostradamus: “software developers will jump off the bandwagon even faster than they got on”; buyers “will think all computers are horrible and throw the whole idea out the window along with their 64.” The Commodore 64 has always evoked special rage from Atari 8-bit loyalists like Freeman. The Atari machines were the 64’s most obvious competitor as fellow low-cost home computers with excellent graphics and sound after weaker sisters like Texas Instruments left the market. They were also arguably the ones the 64 most damaged commercially. “There but for the 64 could have gone the Atari 8-bits,” Atari fans think when they see the 64’s huge success, and not without some justification. But Freeman’s, shall we say, strongly held opinions extended beyond the platform wars. Arcade clones are not just uncreative but morally bankrupt, “illegitimate,” “nasty little pieces of trash.” Programmers doing ports are people “who can’t come up with original subjects for games.” More generally, phrases like “colossal stupidity” and “I almost certainly know more — probably a lot more — about this than you do” creep in a bit too often.

Following the Amiga Archon ports, Free Fall worked for several years on a project that marked a return to Freeman’s roots with Automated Simulations and Temple of Apshai: Swords of Twilight, an ambitious RPG for the Amiga that finally appeared in 1989. It had the unique feature of allowing up to three players to inhabit its world at the same time, each with her own controller, adventuring cooperatively. Despite being released once again by EA, the game seemed to suffer from a dearth of distribution or promotion, and came and went largely without a trace, and without ever being ported beyond the Amiga, a relative minority platform in North America. Another five years elapsed before Free Fall released Archon Ultra, this time on the SSI label. That game was poorly received as adding little to the original, and once again sank quickly into obscurity. And, a few casual card games and the like aside, that’s largely been that from Free Fall. They are still officially a going concern, but seem to exist today largely to license their intellectual property (i.e., Archon) to interested developers. If their output after 1986 or so seems meager given the extraordinary productivity and energy of their first few years, know that my impression — and I must emphasize that this is only an impression, with little data to back it up — is that life has thrown its share of difficulties at Freeman and Westfall since their heydays as stars of Hawkins’s stable of software artists, difficulties that go beyond just some games that performed disappointingly in the marketplace.

If you’d like to try Murder on the Zinderneuf for yourself, I’ve prepared the usual care package for you, with an Atari 8-bit disk image and the (essential) manual. Next time we’ll say goodbye to EA’s Software Artists for a while and catch up with some Implementors again.

(A good interview with Freeman and Westfall can be found online at Halcyon Days, and one with Freeman alone at Now Gamer. Contemporary articles about Free Fall are in the January 1983 Softline, the November 1984 A.N.A.L.O.G., the February 1985 Family Computing, the July/August 1987 Info, and the November 1984 Compute!’s Gazette (Freeman must have been gritting his teeth through that interview, given his opinion of the Commodore 64). Freeman’s Computer Gaming World column ran from the May/June 1983 issue through the April/May 1985 issue.)

Lisa

February 26, 2013 at 8:21 pm

In this sort of genre, I was a fan of Accolade’s later “Killed Until Dead”.

Bill Loguidice

February 26, 2013 at 10:13 pm

Another excellent piece. What always amazed me about Freefall Associates was how obviously difficult it was for them to capture that special magic found in the original Archon. Even when their games bordered on the brilliant or unique, like with Swords of Twilight, it lacked that certain something to push it over the top. I’m not surprised they became disheartened with development over the years. I remember being particularly crushed by Archon Ultra myself, which seemed like the polar opposite of the original game. Luckily, after many failed attempts at recreating Archon, Archon Classic on the PC, though without their direct involvement, obviously, was finally able to capture the same atmosphere, albeit all but completely aping the original. Perhaps there’s just no way to top what Archon had achieved. At least a modern day Zinderneuf could solve many of the original game’s problems, though that’s probably less of a straightforward task all things considered…

Kroc Camen

February 26, 2013 at 11:34 pm

I just tried to play An Act of Murder that you linked to as this sounds most interesting, but there’s really no documentation — so I don’t know what verbs are available to me! It’s 2013, honestly isn’t there an obvious way to list all the verbs that the game supports? Very disappointing :( Freeman wasn’t wrong to complain about the pains of IF!

Jimmy Maher

February 27, 2013 at 10:57 am

I believe if you just type HELP at the first prompt you’ll get a menu that will give a lot of info on how to play.

Kroc Camen

February 27, 2013 at 7:51 pm

Unfortunately, the in-game help seems to be under the jurisdiction of the author (thusly completely scant — who documents the ‘obvious’?), there doesn’t seem to be generic Parchment / Z-Machine documentation and even the Parchment wiki is of no help! It’s a surprise this is so poor. Apparently your Filfre program can show the currently available verbs?

Jimmy Maher

February 27, 2013 at 11:40 pm

Filfre shows a list of common verbs, but doesn’t pull them from the actual game file. For various reasons that start with the very different story formats of different Infocom and Inform compilers, that’s just not really possible.

That said, I think the standard verbs should be about all you need for Act of Murder, long as you remember the ASK/TELL conversation format that’s described in the help. If you’re rusty on your text adventure commands (and there’s certainly no shame in that), you might want to try a beginner-oriented game like Andrew Plotkin’s The Dreamhold. My own King of Shreds and Patches is probably more than you want to bite off right now, but it might be worth starting it just for the interactive tutorial at the beginning.

ZUrlocker

February 27, 2013 at 2:05 am

I found the story of Zinderneuf as a flawed game to be fascinating. You captured the reason precisely: it’s the failed experiment that proves the value of a human-designed story over a computer-generated version. I also agree that “An Act of Murder” works very well as a somewhat computer generated story. While the replay element is not that high, it’s still a strong story with believable, hand-crafted characters.

iPadCary

February 28, 2013 at 11:50 pm

One of my favorite boxcovers ever!

Soren Johnson

September 20, 2014 at 1:30 am

Are we going to hear about Killed Until Dead? I remember enjoying that one quite a bit although my memory of C64 games is not as strong as others from that period. Dynamic mystery stories are a great topic as it SEEMS like they could work but no one really cracked the nut and mostly people have given up on it.

Jimmy Maher

September 20, 2014 at 9:44 am

I’m on the fence a bit right now about covering Killed Until Dead. While unique in other ways, its mysteries are not actually generated dynamically. There are about 20 that come with the game, and once you’ve played them that’s it.

Lisa H.

September 20, 2014 at 9:35 pm

I hope it at least gets a mention, if not anything deeper. I loved that game and played it until the disk wore out.

Jimmy Maher

September 21, 2014 at 9:47 am

My wife and I just spent a very enjoyable evening with it in response to Soren’s comment. So, yeah, I think it will get its due. Quite soon actually. ;)

Narsham

November 23, 2014 at 4:47 pm

I’m not quite sure I agree about the reasons for Zinderneuf’s failings, especially set in comparison with a game like Deadline (which requires save/load/restart sequences to beat). I find myself more taken out of the mystery by being forced to work out where I need to position my detective in order to gather clues, as if I were hacking a mystery novel instead of actually behaving like a real detective. Zinderneuf’s clue-searching these days could be a minigame or involve actual graphical searching; better graphics would allow you to see which suspects have black hair instead of consulting the manual.

This game shines only if you play a larger number of games. Invest the 10-20 hours you might in Deadline and you’ll have all the suspects’ habits and characteristics memorized, know the best way to get 2-3 responses out of each suspect questioning, and know the plots well enough to get caught by red herrings (as the game generates elements of other plots involving suspects who aren’t actually involved in the crime). Several of the detectives are bad enough at finding clues that you need to find other ways to solve cases, so there’s that element as well.

Even as a long-time player I would sometimes be caught out by the random generator. Every so often the clue left at the crime scene is ambiguous enough that it leads you to one of the sub-plots that’s happening on but unrelated (the tontaine plot can be especially troublesome in this regard), but that’s a luck of the draw thing and you need to play the game a lot to run into these difficult cases.

I would also swear that a few of the plots are deliberately set to be rarer than others and only crop up a few times across many plays. But that may just be an artifact of memory or chance.

I’d say the real problem here is that one puzzle has simply been replaced by another. Neither Zinderneuf nor Deadline can offer a single coherent story that can be unraveled in a single playthrough. But the key to a mystery you want to read more than once isn’t the puzzle, it’s the worldbuilding and characterization, and computers weren’t at the point where they could offer enough of that yet outside of the player’s imagination.

Gideon Marcus

February 7, 2017 at 2:40 am

“Yes, Murder on the Zinderneuf‘s narrative generator is clever, but it’s not as clever as, say, Marc Blank, the author of Deadline ”

Is a possessive missing?

When I first played Zinderneuf, I thought clues were hidden in specific places — I didn’t realize you could just wiggle back and forth in a room to find them. Made things more challenging and, perhaps, more engaging.

I loved this game, and I’ve played it countless times.

Thank you for this article!

Mike Taylor

March 2, 2018 at 5:17 pm

“Is a possessive missing?”

I don’t think so. The comparison is between MotZ’s generator, and Marc Blank’s mind.

Mike Taylor

March 2, 2018 at 5:10 pm

“and catch up with some Implementators again” -> “implementors”, I guess?

Jimmy Maher

March 4, 2018 at 11:53 am

Thanks!

Peter Orvetti

July 24, 2019 at 10:05 am

One of the many things I love about this blog is being reminded of games I’d forgotten all about. (My dad had a tendency to buy the New Cool Thing, play it once, then leave it to me.) I adored this game.

I can’t recall; did it make any difference which detective you chose to be?

Phil

October 29, 2020 at 5:41 am

Can you still find a copy with original manuals of the Murder on the Zinderneuf game? I don’t see anything listed online to buy?

Will Moczarski

April 3, 2021 at 7:50 pm

A wonderful article, as usual!

“All of these considerations led to the dynamic, re-playable Murder on the Zinderneuf,”

-> This sounds a bit off, as one of those considerations (the insane prices/the present reality of cheap games in app stores) would require hindsight. Also I might be wrong but weren’t AAA titles even more expensive than $30 or $40 in 1980-83?

Jimmy Maher

April 8, 2021 at 8:08 am

Good point. Thanks!

Jeff Nyman

August 8, 2021 at 7:49 am

“The former part of this claim became increasingly less true as more dynamic, responsive game worlds like that of Deadline were developed…”

Not really, though, right? I think Narsham’s comment (from back in 2014!) is very accurate. Deadline is still basically just a matter of figuring out some of those dynamic elements. There was no element of randomness or adaptation that would change things at all. Once you knew the mechanics, the puzzle was figured out.

I liken this a bit to the later “A Mind Forever Voyaging.” That was just a bigger mystery — and granted, perhaps not as “dynamic” as Deadline. But fundamentally it was really Deadline writ large. Be at certain places at certain times to see certain things.

“to note that no one ever criticizes other forms of art, like books, for not being infinitely re-readable”

Hmmm. This might be a *little* disingenuous to an extent since, obviously, games are designed to be interactive and thus the experience is different. But this also seems to miss the point that many, many reviews of books are all about: “It was okay, but I doubt I’ll ever re-read it.” Other books are ones that people routinely state they have revisited at different points in their life.

And, to be fair, the same is said of games. “Played it once, never cared to again” versus “I keep coming back to this game, even after I’ve won it.” (Said of games like Mass Effect, often.)

Thus:

“Zinderneuf‘s ideal of a narrative that is new every time is neat, and certainly interesting for someone like me to write about as the road almost entirely not taken in adventure games. But are there perhaps good reasons for it to be the road not taken?”

This, to me, is the most interesting part of this article by far and it’s actually interesting to contrast Deadline with this game. But that also leads to:

“designers who see games as rules systems to be carefully crafted and tweaked are often put off by adventure games, which are ultimately all about the fictional context, the lived experience of playing the protagonist in a story.”

Which is perhaps why story-driven, open-world RPG style games are so popular and have come to dominate in many ways. Or consider something like the game “Batman: Arkham Asylum”, which has you investigating various clues left by the riddler and having to investigate areas. I’m by no means comparing that game to Deadline or Zinderneuf, but it’s interesting to consider how some elements of the Batman game could be seen as an evolution.

You can even look at some of the elements of games like “The Witcher 3” or even “Assassins Creed: Origins” (and “Odyssey”), where you often have to figure out certain things on mini-quests that provide a smaller, localized mystery — sometimes tying into the larger narrative.