No one at Origin had much time to bask in the rapturous reception accorded to Wingleader at the 1990 Summer Consumer Electronics Show. Their end-of-September deadline for shipping the game was now barely three months away, and there remained a daunting amount of work to be done.

At the beginning of July, executive producer Dallas Snell called the troops together to tell them that crunch time was beginning in earnest; everyone would need to work at least 55 hours per week from now on. Most of the people on the project only smiled bemusedly at the alleged news flash. They were already working those kinds of hours, and knew all too well that a 55-hour work week would probably seem like a part-timer’s schedule before all was said and done.

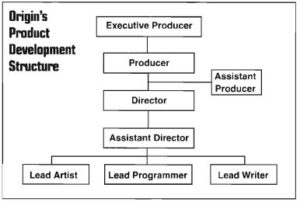

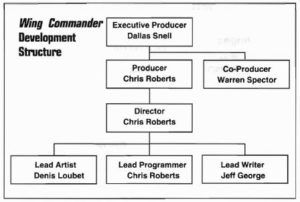

At the beginning of August, Snell unceremoniously booted Chris Roberts, the project’s founder, from his role as co-producer, leaving him with only the title of director. Manifesting a tendency anyone familiar with his more recent projects will immediately recognize, Roberts had been causing chaos on the team by approving seemingly every suggested addition or enhancement that crossed his desk. Snell, the brutal pragmatist in this company full of dreamers, appointed himself as Warren Spector’s new co-producer. His first action was to place a freeze on new features in favor of getting the game that currently existed finished and out the door. Snell:

The individuals in Product Development are an extremely passionate group of people, and I love that. Everyone is here because, for the most part, they love what they’re doing. This is what they want to do with their lives, and they’re very intense about it and very sensitive to your messing around with what they’re trying to accomplish. They don’t live for getting it done on time or having it make money. They live to see this effect or that effect, their visions, accomplished.

It’s always a continual antagonistic relationship between the executive producer and the development teams. I’m always the ice man, the ogre, or something. It’s not fun, but it gets the products done and out. I guess that’s why I have the room with the view. Anyway, at the end of the project, all of Product Development asked me not to get that involved again.

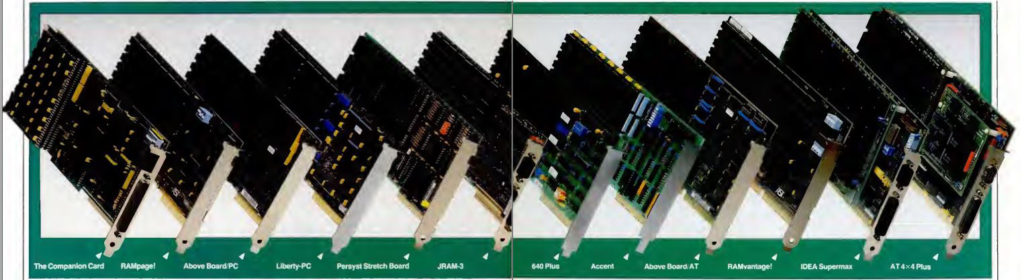

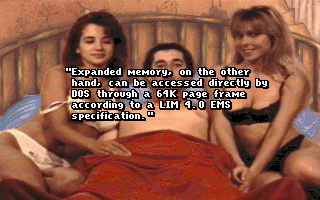

One problem complicating Origin’s life enormously was the open architecture of MS-DOS, this brave new world they’d leaped into the previous year. Back in the Apple II days, they’d been able to write their games for a relatively static set of hardware requirements, give or take an Apple IIGS running in fast mode or a Mockingboard sound card. The world of MS-DOS, by contrast, encompassed a bewildering array of potential hardware configurations: different processors, different graphics and sound cards, different mice and game controllers, different amounts and types of memory, different floppy-disk formats, different hard-disk capacities. For a game like Wingleader, surfing the bleeding edge of all this technology but trying at the same time to offer at least a modicum of playability on older setups, all of this variance was the stuff of nightmares. Origin’s testing department was working 80-hour weeks by the end, and, as we’ll soon see, the final result would still leave plenty to be desired from a quality-control perspective.

As the clock was ticking down toward release, Origin’s legal team delivered the news that it probably wouldn’t be a good idea after all to call the game Wingleader — already the company’s second choice for a name — thanks to a number of existing trademarks on the similar “Wingman.” With little time to devote to yet another naming debate, Origin went with their consensus third choice of Wing Commander, which had lost only narrowly to Wingleader in the last vote. This name finally stuck. Indeed, today it’s hard to imagine Wing Commander under any other name.

The game was finished in a mad frenzy that stretched right up to the end; the “installation guide” telling how to get it running was written and typeset from scratch in literally the last five hours before the whole project had to be packed into a box and shipped off for duplication. That accomplished, everyone donned their new Wing Commander baseball caps and headed out to the front lawn for Origin’s traditional ship-day beer bash. There Robert Garriott climbed onto a picnic table to announce that all of Chris Roberts’s efforts in creating by far the most elaborate multimedia production Origin had ever released had been enough to secure him, at long last, an actual fast job at the company. “As of 5 P.M. this afternoon,” said Garriott, “Chris is Origin’s Director of New Technologies. Congratulations, Chris, and welcome to the Origin team.” The welcome was, everyone had to agree, more than a little belated.

We’ll turn back to Roberts’s later career at Origin in future articles. At this point, though, this history of the original Wing Commander must become the story of the people who played it rather than that of the people who created it. And, make no mistake, play it the people did. Gamers rushed to embrace what had ever since that Summer CES show been the most anticipated title in the industry. Roberts has claimed that Wing Commander sold 100,000 copies in its first month, a figure that would stand as ridiculous if applied to just about any other computer game of the era, but which might just be ridiculous enough to be true in the case of Wing Commander. While hard sales figures for the game or the franchise it would spawn have never to my knowledge been made public, I can feel confident enough in saying that sales of the first Wing Commander soared into the many, many hundreds of thousands of units. The curse of Ultima was broken; Origin now had a game which had not just become a hit in spite of Ultima‘s long shadow, they had a game which threatened to do the unthinkable — to overshadow Ultima in their product catalog. Certainly all indications are that Wing Commander massively outsold Ultima VI, possibly by a factor of two to one or more. It would take a few years, until the release of Doom in 1993, for any other name to begin to challenge that of Wing Commander as the most consistent money spinner in American computer gaming.

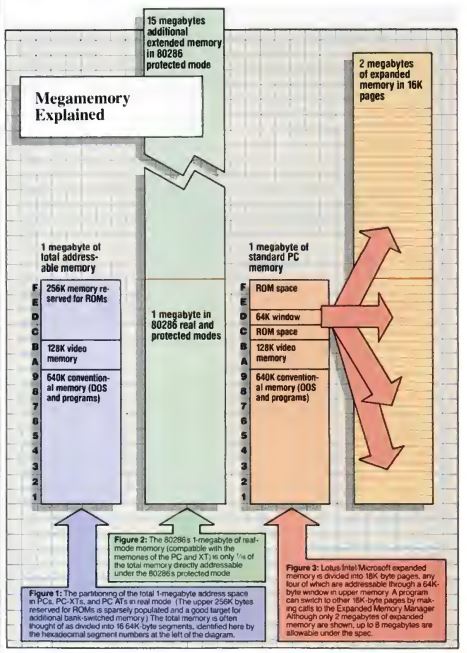

But why should that have been? Why should this particular game of all others have become such a sensation? Part of the reason must be serendipitous timing. During the 1990s as in no decade before or since, the latest developments in hardware would drive sales of games that could show them off to best effect, and Wing Commander set the stage for this trend. Released at a time when 80386-based machines with expanded memory, sound cards, and VGA graphics were just beginning to enter American homes in numbers, Wing Commander took advantage of all those things like no other game on the market. It benefited enormously from this singularity among those who already owned the latest hardware setups, while causing yet many more jealous gamers who hadn’t heretofore seen a need to upgrade to invest in hot machines of their own — the kind of virtuous circle to warm any capitalist’s heart.

Yet there was also something more going on with Wing Commander than just a cool-looking game for showing off the latest hardware, else it would have suffered the fate of the slightly later bestseller Myst: that of being widely purchased, but very rarely actually, seriously played. Unlike the coolly cerebral Myst, Wing Commander was a crowd-pleaser from top to bottom, with huge appeal, even beyond its spectacular audiovisuals, to anyone who had ever thrilled to the likes of a Star Wars film. It was, in other words, computerized entertainment for the mainstream rather than for a select cognoscenti. Just as all but the most incorrigible snobs could have a good time at a Star Wars showing, few gamers of any stripe could resist the call of Wing Commander. In an era when the lines of genre were being drawn more and more indelibly, one of the most remarkable aspects of Wing Commander‘s reception is the number of genre lines it was able to cross. Whether they normally preferred strategy games or flight simulators, CRPGs or adventures, everybody wanted to play Wing Commander.

At a glance, Chris Roberts’s gung-ho action movie of a game would seem to be rather unsuited for the readership of Computer Gaming World, a magazine that had been born out of the ashes of the tabletop-wargaming culture of the 1970s and was still beholden most of all to computer games in the old slow-paced, strategic grognard tradition. Yet the magazine and its readers loved Wing Commander. In fact, they loved Wing Commander as they had never loved any other game before. After reaching the number-one position in Computer Gaming World‘s readers’ poll in February of 1991, it remained there for an unprecedented eleven straight months, attaining already in its second month on top the highest aggregate score ever recorded for a game. When it was finally replaced at number one in January of 1992, the replacement was none other than the new Wing Commander II. Wing Commander I then remained planted right there behind its successor at number two until April, when the magazine’s editors, needing to make room for other games, felt compelled to “retire” it to their Hall of Fame.

In other places, the huge genre-blurring success of Wing Commander prompted an identity crisis. Shay Addams, adventure-game solver extraordinaire, publisher of the Questbusters newsletter and the Quest for Clues series of books, received so many requests to cover Wing Commander that he reported he had been “on the verge of scheduling a brief look” at it. But in the end, he had decided a little petulantly, it “is just a shoot-em-up-in-space game in which the skills necessary are vastly different from those required for completing a quest. (Then again, there is always the possibility of publishing Simulationbusters.)” The parenthetical may have sounded like a joke, but Addams apparently meant it seriously – or, at least, came to mean it seriously. The following year, he started publishing a sister newsletter to Questbusters called Simulations!. It’s hard to imagine him making such a decision absent the phenomenon that was Wing Commander.

So, there was obviously much more to Wing Commander than a glorified tech demo. If we hope to understand what its secret sauce might have been, we need to look at the game itself again, this time from the perspective of a player rather than a developer.

One possibility can be excised immediately. The “space combat simulation” part of the game — i.e., the game part of the game — is fun today and was graphically spectacular back in 1990, but it’s possessed of neither huge complexity nor the sort of tactical or strategic interest that would seem to be required of a title that hoped to spend eleven months at the top of the Computer Gaming World readers’ charts. Better graphics and embodied approach aside, it’s a fairly commonsense evolution of Elite‘s combat engine, complete with inertia and sounds in the vacuum of space and all the other space-fantasy trappings of Star Wars. If we hope to find the real heart of the game’s appeal, it isn’t here that we should look, but rather to the game’s fiction — to the movie Origin Systems built around Chris Roberts’s little shoot-em-up-in-space game.

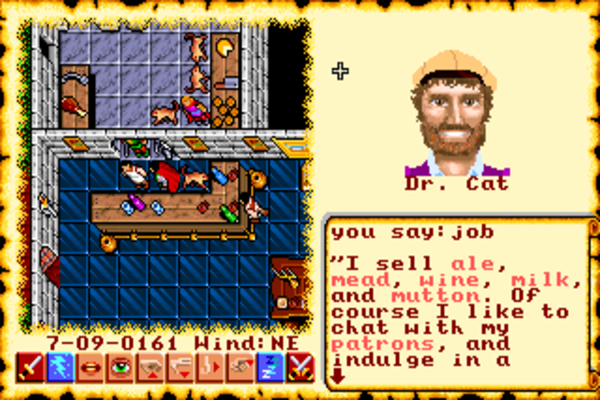

Wing Commander casts you as an unnamed young pilot, square-jawed and patriotic, who has just been assigned to the strike carrier Tiger’s Claw, out on the front lines of humanity’s war against the vicious Kilrathi, a race of space-faring felines. (Cat lovers should approach this game with caution!) Over the course of the game, you fly a variety of missions in a variety of star systems, affecting the course of the wider war as you do so in very simple, hard-branching ways. Each mission is introduced via a briefing scene, and concluded, if you make it back alive, with a debriefing. (If you don’t make it back alive, you at least get the rare pleasure of watching your own funeral.) Between missions, you can chat with your fellow pilots and a friendly bartender in the Tiger’s Claw‘s officers lounge, play on a simulator in the lounge that serves as the game’s training mode, and keep track of your kill count along with that of the other pilots on the squadron blackboard. As you fly missions and your kill count piles up, you rise through the Tiger’s Claw‘s hierarchy from an untested rookie to the steely-eyed veteran on which everyone else in your squadron depends. You also get the chance to fly several models of space-borne fighters, each with its own flight characteristics and weapons loadouts.

The inspirations for Wing Commander as a piece of fiction aren’t hard to find in either the game itself or the many interviews Chris Roberts has given about it over the years. Leaving aside the obvious influence of Star Wars on the game’s cinematic visuals, Wing Commander fits most comfortably into the largely book-bound sub-genre of so-called “military science fiction.” A tradition which has Robert Heinlein’s 1959 novel Starship Troopers as its arguable urtext, military science fiction is less interested in the exploration of strange new worlds, etc., than it is in the exploration of possible futures of warfare in space.

Because worldbuilding is hard and extrapolating the nitty-gritty details of future modes of warfare is even harder, much military science fiction is built out of thinly veiled stand-ins for the military and political history of our own little planet. So, for example, David Weber’s long-running Honor Harrington series transports the Napoleonic Wars into space, while Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War — probably the sub-genre’s best claim to a work of real, lasting literary merit — is based largely on the author’s own experiences in Vietnam. Hewing to this tradition, Wing Commander presents a space-borne version of the grand carrier battles which took place in the Pacific during World War II — entirely unique events in the history of human warfare and, as this author can well attest, sheer catnip to any young fellow with a love of ships and airplanes and heroic deeds and things that go boom. Wing Commander shares this historical inspiration with another of its obvious fictional inspirations, the fun if terminally cheesy 1978 television series Battlestar Galactica. (Come to think of it, much the same description can be applied to Wing Commander.)

Wing Commander is also like Battlestar Galactica in another respect: it’s not so much interested in constructing a detailed technological and tactical framework for its vision of futuristic warfare — leave that stuff to the books! — as it is in choosing whatever thing seems coolest at any given juncture. We know nothing really about how or why any of the stuff in the game works, just that’s it’s our job to go out and blow stuff up with it. Nowhere is that failing, if failing it be, more evident than in the very name of the game. “Wing Commander” is a rank in the Royal Air Force and those of Commonwealth nations denoting an officer in charge of several squadrons of aircraft. It’s certainly not an appropriate designation for the role you play here, that of a rookie fighter pilot who commands only a single wingman. This Wing Commander is called Wing Commander strictly because it sounds cool.

In time, Origin’s decision to start hiring people to serve specifically in the role of writer would have a profound effect on the company’s games, but few would accuse this game, one of Origin’s first with an actual, dedicated “lead writer,” of being deathless fiction. To be fair to David George, it does appear that he spent the majority of his time drawing up the game’s 40 missions, serving in a role that would probably be dubbed “scenario designer” or “level designer” today rather than “writer.” And it’s not as if Chris Roberts’s original brief gave him a whole lot to work with. This is, after all, a game where you’re going to war against a bunch of anthropomorphic house cats. (Our cat told me she thought about conquering the galaxy once or twice, but she wasn’t sure she could fit it into the three hours per day she spends awake.) The Kilrathi are kind of… well, there’s just no getting around it, is there? The whole Kilrathi thing is pretty stupid, although it does allow your fellow pilots to pile on epithets like “fur balls,” “fleabags,” and, my personal favorite, “Killie-cats.”

Said fellow pilots are themselves a collection of ethnic stereotypes so over-the-top as to verge on the offensive if it wasn’t so obvious that Origin just didn’t have a clue. Spirit is Japanese, so of course she suffixes every name with “-san” or “-sama” even when speaking English, right? And Angel is French, so of course she says “bonjour” a lot, right? Right?

My second favorite Wing Commander picture comes from the manual rather than the game proper. Our cat would look precisely this bitchy if I shoved her into a spacesuit.

Despite Chris Roberts’s obvious and oft-stated desire to put you into an interactive movie, there’s little coherent narrative arc to Wing Commander, even by action-movie standards. Every two to four missions, the Tiger’s Claw jumps to some other star system and some vague allusion is made to the latest offensive or defensive operation, but there’s nothing to really hang your hat on in terms of a clear unfolding narrative of the war. A couple of cut scenes do show good or bad events taking place elsewhere, based on your performance in battle — who knew one fighter pilot could have so much effect on the course of a war? — but, again, there’s just not enough detail to give a sense of the strategic situation. One has to suspect that Origin didn’t know what was really going on any better than the rest of us.

My favorite Wing Commander pictures, bar none. What I love best about these and the picture above is the ears on the helmets. And what I love best about the ears on the helmets is that there’s no apparent attempt to be cheeky or funny in placing them there. (One thing this game is totally devoid of is deliberate humor. Luckily, there’s plenty of non-deliberate humor to enjoy.) Someone at Origin said, “Well, they’re cats, so they have to have space in their helmets for their ears, right?” and everyone just nodded solemnly and went with it. If you ask me, nothing illustrates Wing Commander‘s charming naivete better than this.

In its day, Wing Commander was hugely impressive as a technological tour de force, but it’s not hard to spot the places where it really suffered from the compressed development schedule. There’s at least one place, for example, where your fellow pilots talk about an event that hasn’t actually happened yet, presumably due to last minute juggling of the mission order. More serious are the many and varied glitches that occur during combat, from sound drop-outs to the occasional complete lock-up. Most bizarrely of all to our modern sensibilities, Origin didn’t take the time to account for the speed of the computer running the game. Wing Commander simply runs flat-out all the time, as fast as the hosting computer can manage. This delivered a speed that was just about perfect on a top-of-the-line 80386-based machine of 1990, but that made it effectively unplayable on the next generation of 80486-based machines that started becoming popular just a couple of years later; this game was definitely not built with any eye to posterity. Wing Commander would wind up driving the development of so-called “slowdown” programs that throttled back later hardware to keep games like this one playable.

Still, even today Wing Commander remains a weirdly hard nut to crack in this respect. For some reason, presumably involving subtle differences between real and emulated hardware, it’s impossible to find an entirely satisfactory speed setting for the game in the DOSBox emulator. A setting which seems perfect when flying in open space slows down to a crawl in a dogfight; a setting which delivers a good frame rate in a dogfight is absurdly fast when fewer other ships surround you. The only apparent solution to the problem is to adjust the DOSBox speed settings on the fly as you’re trying not to get shot out of space by the Kilrathi — or, perhaps more practically, to just find something close to a happy medium and live with it. One quickly notices when reading about Wing Commander the wide variety of opinions about its overall difficulty, from those who say it’s too easy to those who say it’s way too hard to those who say it’s just right. I wonder whether this disparity is down to the fact that, thanks to the lack of built-in throttling, everyone is playing a slightly different version of the game.

The only thing worse than being a cat lover in this game is being a pacifist. And everyone knows cats don’t like water, Shotglass… sheesh.

It becomes clear pretty quickly that the missions are only of a few broad types, encompassing patrols, seek-and-destroy missions, and escort missions (the worst!), but the context provided by the briefings keeps things more interesting than they might otherwise be, as do the variety of spacecraft you get to fly and fight against. The mission design is pretty good, although the difficulty does ebb and spike a bit more than it ideally might. In particular, one mission found right in the middle of the game — the second Kurosawa mission, for those who know the game already — is notorious for being all but impossible. Chris Roberts has bragged that the missions in the finished game “were exactly the ones that Jeff George designed on paper — we didn’t need to do any balancing at all!” In truth, I’m not sure the lack of balancing isn’t a bug rather than a feature.

Roberts’s decision to allow you to take your lumps and go on even when you fail at a mission was groundbreaking at the time. Yet, having made this very progressive decision, he then proceeded to implement it in the most regressive way imaginable. When you fail in Wing Commander, the war as a whole goes badly, thanks again to that outsize effect you have upon it, and you get punished by being forced to fly against even more overwhelming odds in inferior fighters. Imagine, then, what it’s like to play Wing Commander honestly, without recourse to save games, as a brand new player. Still trying to get your bearings as a rookie pilot, you don’t perform terribly well in the first two or three missions. In response, your commanding officer delivers a constant drumbeat of negative feedback, while the missions just keep getting harder and harder at what feels like an almost exponential pace, ensuring that you continue to suck every time you fly. By the time you’ve failed at 30 missions and your ineptitude has led to the Tiger’s Claw being chased out of the sector with its (striped?) tail between its legs, you might just need therapy to recover from the experience.

What ought to happen, of course, is that failing at the early missions should see you assigned to easier rather than harder ones — no matter the excuse; Origin could make something up on the fly, as they so obviously did so much of the game’s fiction — that give you a chance to practice your skills. Experienced, hardcore players could still have their fun by trying to complete the game in as few missions as possible, while newcomers wouldn’t have to feel like battered spouses. Or, if such an elegant solution wasn’t possible, Origin could at least have given us player-selectable difficulty levels.

As it is, the only practical way to play as a newcomer is to ignore all of Origin’s exhortations to play honestly and just keep reloading until you successfully complete each mission; only in this way can you keep the escalating difficulty manageable. (The one place where I would recommend that you take your lumps and continue is in the aforementioned second Kurosawa mission. Losing here will throw you briefly off-track, but the missions that follow aren’t too difficult, and it’s easier to play your way to victory through them than to try to beat Mission Impossible.) This approach, it should be noted, drove Chris Roberts crazy; he considered it nothing less than a betrayal of the entire premise around which he’d designed his game. Yet he had only himself to blame. Like much in Wing Commander, the discrepancy between the game Roberts wants to have designed and the one he’s actually designed speaks to the lack of time to play it extensively before its release, and thereby to shake all these problems out.

And yet. And yet…

Having complained at such length about Wing Commander, I find myself at something of an impasse, in that my overall verdict on the game is nowhere near as negative as these complaints would imply. It’s not even a case of Wing Commander being, like, say, most of the Ultima games, a groundbreaking work in its day that’s a hard sell today. No, Wing Commander is a game I continue to genuinely enjoy despite all its obvious problems.

In writing about all these old games over the years, I’ve noticed that those titles I’d broadly brand as classics and gladly recommend to contemporary players tend to fall into two categories. There are games like, say, The Secret of Monkey Island that know exactly what they’re trying to do and proceed to do it all almost perfectly, making all the right choices; it’s hard to imagine how to improve these games in any but the tiniest of ways within the context of the technology available to their developers. And then there are games like Wing Commander that are riddled with flaws, yet still manage to be hugely engaging, hugely fun, almost in spite of themselves. Who knows, perhaps trying to correct all the problems I’ve spent so many words detailing would kill something ineffably important in the game. Certainly the many sequels and spinoffs to the original Wing Commander correct many of the failings I’ve described in this article, yet I’m not sure any of them manage to be a comprehensively better game. Like so many creative endeavors, game design isn’t a zero-sum game. Much as I loathe the lazy critic’s cliché “more than the sum of its parts,” it feels hard to avoid it here.

It’s true that many of my specific criticisms have an upside to serve as a counterpoint. The fiction may be giddy and ridiculous, but it winds up being fun precisely because it’s so giddy and ridiculous. This isn’t a self-conscious homage to comic-book storytelling of the sort we see so often in more recent games from this Age of Irony of ours. No, this game really does think this stuff it’s got to share with you is the coolest stuff in the world, and it can’t wait to get on with it; it lacks any form of guile just as much as it does any self-awareness. In this as in so many other senses, Wing Commander exudes the personality of its creator, helps you to understand why it was that everyone at Origin Systems so liked to have this high-strung, enthusiastic kid around them. There’s an innocence about the game that leaves one feeling happy that Chris Roberts was steered away from his original plans for a “gritty” story full of moral ambivalence; one senses that he wouldn’t have been able to do that anywhere near as well as he does this. Even the Kilrathi enemies, silly as they are, take some of the sting out of war; speciesist though the sentiment may be, at least it isn’t people you’re killing out there. Darned if the fiction doesn’t win me over in the end with its sheer exuberance, all bright primary emotions to match the bright primary colors of the VGA palette. Sometimes you’re cheering along with it, sometimes you’re laughing at it, but you’re always having a good time. The whole thing is just too gosh-darned earnest to annoy me like most bad writing does.

Even the rogue’s gallery of ethnic stereotypes that is your fellow pilots doesn’t grate as much as it might. Indeed, Origin’s decision to include lots of strong, capable women and people of color among the pilots should be applauded. Whatever else you can say about Wing Commander, its heart is almost always in the right place.

Winning a Golden Sun for “surviving the destruction of my ship.” I’m not sure, though, that “sacrificing my vessel” was really an act of bravery, under the circumstances. Oh, well, I’ll take whatever hardware they care to give me.

One thing Wing Commander understands very well is the value of positive reinforcement — the importance of, as Sid Meier puts it, making sure the player is always the star of the show. In that spirit, the kill count of even the most average player will always advance much faster on the squadron’s leader board than that of anyone else in the squadron. As you play through the missions, you’re given promotions and occasionally medals, the latter delivered amidst the deafening applause of your peers in a scene lifted straight from the end of the first Star Wars film (which was in turn aping the Nuremberg Rally shown in Triumph of the Will, but no need to think too much about that in this giddy context). You know at some level that you’re being manipulated, just as you know the story is ridiculous, but you don’t really care. Isn’t this feeling of achievement a substantial part of the reason that we play games?

Another thing Wing Commander understands — or perhaps stumbled into accidentally thanks to the compressed development schedule — is the value of brevity. Thanks to the tree structure that makes it impossible to play all 40 missions on any given run-through, a typical Wing Commander career spans no more than 25 or 30 missions, most of which can be completed in half an hour or so, especially if you use the handy auto-pilot function to skip past all the point-to-point flying and just get to the places where the shooting starts. (Personally, I prefer the more organic feel of doing all the flying myself, but I suspect I’m a weirdo in this as in so many other respects.) The relative shortness of the campaign means that the game never threatens to run into the ground the flight engine’s rather limited box of tricks. It winds up leaving you wanting more rather than trying your patience. For all these reasons, and even with all its obvious problems technical and otherwise, Wing Commander remains good fun today.

Which doesn’t of course mean that any self-respecting digital antiquarian can afford to neglect its importance to gaming history. The first blockbuster of the 1990s and the most commercially dominant franchise in computer gaming until the arrival of Doom in 1993 shook everything up yet again, Wing Commander can be read as cause or symptom of the changing times. There was a sense even in 1990 that Wing Commander‘s arrival, coming so appropriately at the beginning of a new decade, marked a watershed moment, and time has only strengthened that impression. Chris Crawford, this medium’s eternal curmudgeon — every creative field needs one of them to serve as a corrective to the hype-merchants — has accused Wing Commander of nothing less than ruining the culture of gaming for all time. By raising the bar so high on ludic audiovisuals, runs his argument, Wing Commander dramatically raised the financial investment necessary to produce a competitive game. This in turn made publishers, reluctant to risk all that capital on anything but a sure bet, more conservative in the sorts of projects they were willing to approve, causing more experimental games with only niche appeal to disappear from the market. “It became a hit-driven industry,” Crawford says. “The whole marketing strategy, economics, and everything changed, in my opinion, much for the worse.”

There’s some truth to this assertion, but it’s also true that publishers had been growing more conservative and budgets had been creeping upward for years before Wing Commander. By 1990, Infocom’s literary peak was years in the past, as were Activison’s experimental period and Electronic Arts’s speculations on whether computers could make you cry. In this sense, then, Wing Commander can be seen as just one more point on a trend line, not the dramatic break which Crawford would claim it to be. Had it not come along when it did to raise the audiovisual bar, something else would have.

Where Wing Commander does feel like a cleaner break with the past is in its popularizing of the use of narrative in a traditionally non-narrative-driven genre. This, I would assert, is the real source of the game’s appeal, then and now. The shock and awe of seeing the graphics and hearing the sound and music for the first time inevitably faded even back in the day, and today of course the whole thing looks garish and a little kitschy with those absurdly big pixels. And certainly the space-combat game alone wasn’t enough to sustain obsessive devotion back in the day, while today the speed issues can at times make it more than a little exasperating to actually play Wing Commander at all. But the appeal of, to borrow from Infocom’s old catch-phrase, waking up inside a story — waking up inside a Star Wars movie, if you like — and being swept along on a rollicking, semi-interactive ride is, it would seem, eternal. It may not have been the reason most people bought Wing Commander in the early 1990s — that had everything to do with those aforementioned spectacular audiovisuals — but it was the reason they kept playing it, the reason it remained the best single computer game in the country according to Computer Gaming World‘s readers for all those months. Come for the graphics and sound, stay for the story. The ironic aspect of all this is that, as I’ve already noted, Wing Commander‘s story barely qualified as a story at all by the standards of conventional fiction. Yet, underwhelming though it was on its own merits, it worked more than well enough in providing structure and motivation for the individual missions.

The clearest historical antecedent to Wing Commander must be the interactive movies of Cinemaware, which had struggled to combine cinematic storytelling with modes of play that departed from traditional adventure-game norms throughout the second half of the 1980s, albeit with somewhat mixed success. John Cutter, a designer at Cinemaware, has described how Bob Jacob, the company’s founder and president, reacted to his first glimpse of Wing Commander: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen him look so sad.” With his company beginning to fall apart around him, Jacob had good reason to feel sad. He least of all would have imagined Origin Systems — they of the aesthetically indifferent CRPG epics — as the company that would carry the flag of cinematic computer gaming forward into the new decade, but the proof was right there on the screen in front of him.

There are two accounts, both of them true in their way, to explain how the adventure game, a genre that in the early 1990s was perhaps the most vibrant and popular in computer gaming, ended the decade an irrelevancy to gamers and publishers alike. One explanation, which I’ve gone into a number of times already on this blog, focuses on a lack of innovation and, most of all, a lack of good design practices among far too many adventures developers; these lacks left the genre identified primarily with unfun pixel hunts and illogical puzzles in the minds of far too many players. But another, more positive take on the subject says that adventure games never really went away at all: their best attributes were rather merged into other genres. Did adventure games disappear or did they take over the world? As in so many cases, the answer depends on your perspective. If you focus on the traditional mechanics of adventure games — exploring landscapes and solving puzzles, usually non-violently — as their defining attributes, the genre did indeed go from thriving to all but dying in the course of about five years. If, on the other hand, you choose to see adventure games more broadly as games where you wake up inside a story, it can sometimes seem like almost every game out there today has become, whatever else it is, an adventure game.

Wing Commander was the first great proof that many more players than just adventure-game fans love story. Players love the way a story can make them feel a part of something bigger as they play, and, more prosaically but no less importantly, they love the structure it can give to their play. One of the dominant themes of games in the 1990s would be the injection of story into genres which had never had much use for it before: the unfolding narrative of discovery built into the grand-strategy game X-COM, the campaign modes of the real-time-strategy pioneers Warcraft and Starcraft, the plot that gave meaning to all the shooting in Half-Life. All of these are among the most beloved titles of the decade, spawning franchises that remain more than viable to this day. One has to assume this isn’t a coincidence. “The games I made were always about narrative because I felt that was missing for me,” says Chris Roberts. “I wanted that sense of story and progression. I felt like I wasn’t getting that in games. That was one of my bigger drives when I was making games, was to get that, that I felt like I really wanted and liked from other media.” Clearly many others agreed.

(Sources: the books Wing Commander I and II: The Ultimate Strategy Guide by Mike Harrison and Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; Retro Gamer 59 and 123; Questbusters of July 1989, August 1990, and April 1991; Computer Gaming World of September 1989 and November 1992; Amiga Computing of December 1988. Online sources include documents hosted at the Wing Commander Combat Information Center, US Gamer‘s profile of Chris Roberts, The Escapist‘s history of Wing Commander, Paul Dean’s interview with Chris Roberts, and Matt Barton’s interview with George “The Fat Man” Sanger. Last but far from least, my thanks to John Miles for corresponding with me via email about his time at Origin, and my thanks to Casey Muratori for putting me in touch with him.

Wing Commander I and II can be purchased in a package together with all of their expansion packs from GOG.com.)