At the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in June of 1989, Origin Systems and Brøderbund Software announced that they wouldn’t be renewing the distribution contract the former had signed with the latter two years before. It was about as amicable a divorce as has ever been seen in the history of business; in this respect, it could hardly have stood in greater contrast to the dust-up that had ended Origin’s relationship with Electronic Arts, their previous distributor, in 1987. Each company was full of rosy praise and warm wishes for the other at a special “graduation party” Brøderbund threw for Origin at the show. “Brøderbund has been one of the few affiliated-label programs that truly helps a small company grow to a size where it can stand on its own and enter the real world,” said Origin’s Robert Garriott, making oblique reference to the more predatory approach of Electronic Arts. In response, Brøderbund’s Gary Carlston toasted that “it’s been rewarding to have helped Origin pursue its growth, and it’s exciting to see the company take this step,” confirming yet one more time Brøderbund’s well-earned reputation as the nice guys of their industry who somehow kept managing to finish first. And so, with a last slap on the rump and a final chorus of “Kumbaya,” Brøderbund sent Origin off to face the scary “world of full-service software publishing” alone.

It was a bold step for Origin, especially given that they still hadn’t solved a serious problem that had dogged them since their founding in the Garriott brothers’ family garage six years earlier. The first two games released by the young company back in 1983 had been Ultima III, the latest installment in Richard Garriott’s genre-defining CRPG series, and Caverns of Callisto, an action game written by Richard’s high-school buddy Chuck Bueche. Setting the frustrating pattern for what was to come, Ultima III soared up the bestseller charts, while Caverns of Callisto disappeared without a trace. In the years that followed, Origin released some non-Ultima games that were moderately successful, but never came close to managing a full-on hit outside of their signature franchise. This failure left them entirely dependent for their survival on Richard Garriott coming up with a new and groundbreaking Ultima game every couple of years, and on that game then proceeding to sell over 200,000 copies. Robert Garriott, as shrewd a businessman as any in his industry, knew that staking his company’s entire future on a single game every two years was at best a risky way to run things. Yet, try as he might, he couldn’t seem to break the pattern.

Origin had a number of factors working against them in their efforts to diversify, but the first and most ironic among them must be the very outsize success of Ultima itself. The company had become so identified with Ultima that many gamers barely realized that they did anything else. As for other folks working in the industry, they had long jokingly referred to Origin Systems as “Ultima Systems.” Everyone knew that the creator of Ultima was also the co-founder of Origin, and the brother of the man who directed its day-to-day operations. In such a situation, there must be a real question of whether any other game project, even a potentially great one, could avoid being overshadowed by the signature franchise, could find enough oxygen to thrive. Added to these concerns, which would be applicable to any company in such a situation, must be the unique nature of the cast of characters at Origin. Richard Garriott’s habit of marching around trade-show floors in full Lord British regalia, his entourage in tow, didn’t always endear him to the rest of the industry. There were, it sometimes seemed, grounds to question whether Richard himself knew that he wasn’t actually a monarch, just a talented kid from suburban Houston with nary a drop of royal blood coursing through his veins. At times, Origin Systems could feel perilously close to a cult of personality. Throw in the company’s out-of-the-way location in Austin, Texas, and attracting really top-flight projects became quite a challenge for them.

So, when it came to games that weren’t Ultima Origin had had to content themselves with projects one notch down from the top tier — projects which, whether because they weren’t flashy enough or were just too nichey, weren’t of huge interest to the bigger publishers. Those brought in enough revenue to justify their existence but not much more, and thus Robert Garriott continued to bet the company every two years on his brother’s latest Ultima. It was a nerve-wracking way to live.

And then, in 1990, all that changed practically overnight. This article and the one that follows will tell the story of how the house that Ultima built found itself with an even bigger franchise on its hands.

By the end of the 1980s, the North American and European computer-game industries, which had heretofore existed in almost total isolation from one another, were becoming slowly but steadily more interconnected. The major American publishers were setting up distribution arms in Europe, and the smaller ones were often distributing their wares through the British importer U.S. Gold. Likewise, the British Firebird and Rainbird labels had set up offices in the United States, and American publishers like Cinemaware were doing good business importing British games for American owners of the Commodore Amiga, a platform that was a bit neglected by domestic developers. But despite these changes, the industry as a whole remained a stubbornly bifurcated place. European developers remained European, American developers remained American, and the days of a truly globalized games industry remained far in the future. The exceptions to these rules stand out all the more thanks to their rarity. And one of these notable exceptions was Chris Roberts, the young man who would change Origin Systems forever.

With a British father and an American mother, Chris Roberts had been a trans-Atlantic sort of fellow right from the start. His father, a sociologist at the University of Manchester, went with his wife to Guatemala to do research shortly after marrying, and it was there that Chris was conceived in 1967. The mother-to-be elected to give birth near her family in Silicon Valley. (From the first, it seems, computers were in the baby’s blood.) After returning for a time to Guatemala, where Chris’s father was finishing his research, the little Roberts clan settled back in Manchester, England. A second son arrived to round out the family in 1970.

His first international adventure behind him, Chris Roberts grew up as a native son of Manchester, developing the distinct Mancunian intonation he retains to this day along with his love of Manchester United football. When first exposed to computers thanks to his father’s position at Manchester University, the boy was immediately smitten. In 1982, when Chris was 14, his father signed him up for his first class in BASIC programming and bought a BBC Micro for him to practice on at home. As it happened, the teacher of that first programming class became a founding editor of the new magazine BBC Micro User. Hungry for content, the magazine bought two of young Chris’s first simple BASIC games to publish as type-in listings. Just like that, he was a published game developer.

Britain at the time was going absolutely crazy for computers and computer games, and many of the new industry’s rising stars were as young or younger than Roberts. It thus wasn’t overly difficult for him to make the leap to designing and coding boxed games to be sold in stores. Imagine Software published his first such, a platformer called Wizadore, in 1985; Superior Software published a second, a side-scrolling shooter called Stryker’s Run, in 1986. But the commercial success these titles could hope to enjoy was limited by the fact that they ran on the BBC Micro, a platform which was virtually unknown outside of Britain and even inside of its home country was much less popular than the Sinclair Spectrum as a gaming machine. Being amply possessed of the contempt most BBC Micro owners felt toward the cheap and toy-like “Speccy,” Roberts decided to shift his attention instead to the Commodore 64, the most popular gaming platform in the world at the time. This decision, combined with another major decision made by his parents, set him on his unlikely collision course with Origin Systems in far-off Austin, Texas.

In early 1986, Roberts’s father got an offer he couldn’t refuse in the form of a tenured professorship at the University of Texas. After finishing the spring semester that year, he, his wife, and his younger son thus traded the gray skies of Manchester for the sunnier climes of Austin. Chris was just finishing his A-Levels at the time. Proud Mancunian that he was, he declared that he had no intention of leaving England — and certainly not for a hick town in the middle of Texas. But he had been planning all along to take a year off before starting at the University of Manchester, and his parents convinced him to at least join the rest of the family in Austin for the summer. He agreed, figuring that it would give him a chance to work free of distractions on a new action/adventure game he had planned as his first project for the Commodore 64. Yet what he actually found in Austin was lots of distractions — eye-opening distractions to warm any young man’s heart. Roberts:

The weather was a little nicer in Austin. The American girls seemed to like the English accent, which wasn’t bad, and there was definitely a lot… everything seemed like it was cheaper and there was more of it, especially back then. Now, the world’s become more homogenized so there’s not things you can only get in America that you don’t get in England as well. Back then it was like, the big American movies would come out in America and then they would come out in England a year later and stuff. So I came over and was like, “Ah, you know, this is pretty cool.”

There were also the American computers to consider; these tended to be much more advanced than their British counterparts, sporting disk drives as universal standard equipment at a time when most British games — including both of Roberts’s previous games — were still published on cassette tapes. In light of all these attractions, it seems doubtful whether Roberts would have kept his resolution to return to Manchester in any circumstances. But there soon came along the craziest of coincidences to seal the deal.

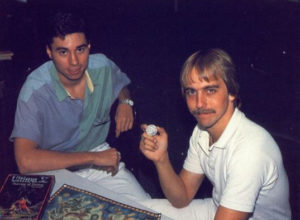

Roberts had decided that he really needed to find an artist to help him with his Commodore 64 game-in-progress. Entering an Austin tabletop-gaming shop one day, he saw a beautiful picture of a gladiator hanging on the wall. The owner of the shop told him the picture had been drawn by a local artist, and offered to call the artist for him right then and there if Roberts was really interested in working with him. Roberts said yes, please do. The artist in question was none other than Denis Loubet, whose professional association with Richard Garriott stretched back to well before Origin Systems had existed, to when he’d drawn the box art for the California Pacific release of Akalabeth in 1980.

After years of working as a contractor, Loubet was just about to be hired as Origin’s first regular in-house artist. Nevertheless, he liked Roberts and thought his game had potential, and agreed to do the art for it as a moonlighting venture. Loubet soon showed what he was working on to Richard Garriott and Dallas Snell, the latter of whom tended to serve as a sort of liaison between the business side of the company, in the person of Robert Garriott, and the creative side, in the person of Richard. All three parties were as impressed by the work-in-progress as Loubet had been, and they invited Chris to Origin’s offices to ask if he’d be interested in publishing it through them. Prior to this point, Roberts had never even heard of Origin Systems or the Ultima series; he’d grown up immersed in the British gaming scene, where neither had any presence whatsoever. But he liked the people at Origin, liked the atmosphere around the place, and perhaps wasn’t aware enough of what the company represented to be leery of it in the way of other developers who were peddling promising projects around the industry. “After my experiences in England, which is like swimming in a big pool of sharks,” he remembers, “I felt comfortable dealing with Origin.”

All thoughts of returning to England had now disappeared. Working from Origin’s offices, albeit still as a contracted outside developer rather than an employee, Roberts finished his game, which came to be called Times of Lore. In the course of its development, the game grew considerably in scope and ambition, and, as seemed only appropriate given the company that was to publish it, took on some light CRPG elements as well. In much of this, Roberts was inspired by David Joiner’s 1987 action-CRPG The Faery Tale Adventure. American influences aside, though, Times of Lore still fit best of all into the grand British tradition of free-scrolling, free-roaming 8-bit action/adventures, a sub-genre that verged on completely unknown to American computer gamers. Roberts made sure the whole game could fit into the Commodore 64’s memory at once to facilitate a cassette-based version for the European market.

Unfortunately, his game got to enjoy only a middling level of sales success in return for all his efforts. As if determined to confirm the conventional wisdom that had caused so many developers to steer clear of them, Origin released Times of Lore almost simultaneously with the Commodore 64 port of Ultima V in 1988, leaving Roberts’s game overshadowed by Lord British’s latest. And in addition to all the baggage that came with the Origin logo in the United States, Times of Lore suffered all the disadvantages of being a pioneer of sorts in Europe, the first Origin title to be pushed aggressively there via a new European distribution contract with MicroProse. While that market would undoubtedly have understood the game much better had they given it a chance, no one there yet knew what to make of the company whose logo was on the box. Despite its strengths, Times of Lore thus failed to break the pattern that had held true for Origin for so long. It turned into yet another non-Ultima that was also a non-hit.

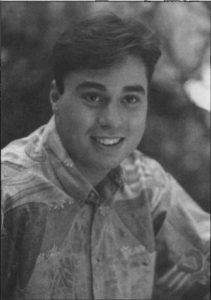

But whatever the relative disappointments, Times of Lore at least wasn’t a flop, and Chris Roberts stayed around as a valued member of the little Origin family. Part of the reason the Origin people wanted to keep him around was simply because they liked him so much. He nursed the same passions for fantasy and science fiction as most of them, with just enough of a skew provided by his British upbringing to make him interesting. And he positively radiated energy and enthusiasm. He’s never hard to find in Origin group shots of the time. His face stands out like that of a nerdy cherub — he had never lost his facial baby fat, making him look pudgier in pictures than he was in real life — as he beams his thousand-kilowatt smile at all and sundry. Still, it was hardly his personality alone that made him such a valued colleague; the folks at Origin also came to have a healthy respect for his abilities. Indeed, and as we’ve already seen in an earlier article, the interface of Times of Lore had a huge influence on that of no less vital an Origin game than Ultima VI.

Alas, Roberts’s own next game for Origin would be far less influential. After flirting for a while with the idea of doing a straightforward sequel to Times of Lore, he decided to adapt the engine to an even more action-oriented post-apocalyptic scenario. Roberts’s first game for MS-DOS, Bad Blood was created in desultory fits and starts, one of those projects that limps to completion more out of inertia than passion. Released at last in 1990, it was an ugly flop on both sides of the Atlantic. Roberts blames marketplace confusion at least partially for its failure: “People who liked arcade-style games didn’t buy it because they thought Bad Blood would be another fantasy-role-play-style game. It was the worst of both worlds, a combination of factors that contributed to its lack of success.” In reality, though, the most telling factor of said combination was just that Bad Blood wasn’t very good, evincing little of the care that so obviously went into Times of Lore. Reviewers roundly panned it, and buyers gave it a wide berth. Thankfully for Chris Roberts’s future in the industry, the game that would make his name was already well along at Origin by the time Bad Blood finally trickled out the door.

Had it come to fruition in its original form, Roberts’s third game for Origin would have marked even more of a departure for him than the actual end result would wind up being. Perhaps trying to fit in better with Origin’s established image, he had the idea of doing, as he puts it, “a space-conquest game where you take over star systems, move battleships around, and invade planets. It was going to be more strategic than my earlier games.” But Roberts always craved a little more adrenaline in his designs than such a description would imply, and it didn’t take him long to start tinkering with the formula. The game moved gradually from strategic battles between slow-moving dreadnoughts in space to manic dogfights between fighter planes in space. In other words, to frame the shift the way the science-fiction-obsessed Roberts might well have chosen, his inspiration for his space battles changed from Star Trek to Star Wars. He decided “it would be more fun flying around in a fighter than moving battleships around the screen”; note the (unconscious?) shift in this statement from the player as a disembodied hand “moving” battleships around to the player as an embodied direct participant “flying around” herself in fighters. Roberts took to calling his work-in-progress Squadron.

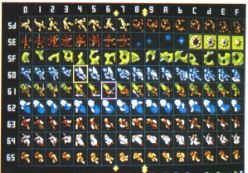

To bring off his idea for an embodied space-combat experience, Roberts would have to abandon the overhead views used by all his games to date in favor of a first-person out-the-cockpit view, like that used by a game he and every other BBC Micro veteran knew well, Ian Bell and David Braben’s Elite. “It was the first space game in which I piloted a ship in combat,” says Roberts of Elite, “and it opened my eyes to the possibilities of where it could go.” On the plus side, Roberts knew that this and any other prospective future games he might make for Origin would be developed on an MS-DOS machine with many times the processing power of the little BBC Micro (or, for that matter, the Commodore 64). On the negative side, Roberts wasn’t a veritable mathematics genius like Ian Bell, the mastermind behind Elite‘s 3D graphics. Nor could he get away in the current marketplace with the wire-frame graphics of Elite. So, he decided to cheat a bit, both to simplify his life and to up the graphics ante. Inspired by the graphics of the Lucasfilm Games flight simulator Battlehawks 1942, he used pre-rendered bitmap images showing ships from several different sides and angles, which could then be scaled to suit the player’s out-the-cockpit view, rather than making a proper, mathematically rigorous 3D engine built out of polygons. As becomes clear all too quickly to anyone who plays the finished game, the results could be a little wonky, with views of the ships suddenly popping into place rather than smoothly rotating. Nevertheless, the ships themselves looked far better than anything Roberts could possibly have hoped to achieve on the technology of the time using a more honest 3D engine.

Denis Loubet, Roberts’s old partner in crime from the early days of Times of Lore, agreed to draw a cockpit as part of what must become yet another moonlighting gig for both of them; Roberts was officially still supposed to be spending his days at Origin on Bad Blood, while Loubet was up to his eyebrows in Ultima VI. Even at this stage, they were incorporating little visceral touches into Squadron, like the pilot’s hand moving the joystick around in time with what the player was doing with her own joystick in front of the computer screen. As the player’s ship got shot up, the damage was depicted visually there in the cockpit. Like the sparks and smoke that used to burst from the bridge controls on the old Star Trek episodes, it might not have made much logical sense — haven’t any of these space-faring societies invented fuses? — but it served the purpose of creating an embodied, visceral experience. Roberts:

It really comes from wanting to put the player in the game. I don’t want you to think you’re playing a simulation, I want you to think you’re really in that cockpit. When I visualized what it would be like to sit in a cockpit, those are the things I thought of.

I took the approach that I didn’t want to sacrifice that reality due to the game dynamics. If you would see wires hanging down after an explosion, then I wanted to include it, even if it would make it harder to figure out how to include all the instruments and readouts. I want what’s taking place inside the cockpit to be as real as what I’m trying to show outside it, in space. I’d rather show you damage as if you were there than just display something like “damage = 20 percent.” That’s abstract. I want to see it.

Squadron, then, was already becoming an unusually cinematic space-combat “simulation.” Because every action-movie hero needs a sidekick, Roberts added a wingman to the game, another pilot who would fly and fight at the player’s side. The player could communicate with the wingman in the midst of battle, passing him orders, and the wingman in turn would communicate back, showing his own personality; he might even refuse to obey orders on occasion.

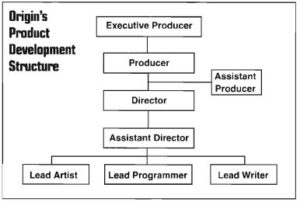

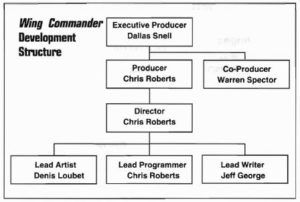

As a cinematic experience, Squadron felt very much in tune with the way things in general were trending at Origin, to such an extent that one might well ask who was influencing whom. Like so many publishers in this era in which CD-ROM and full-motion video hovered alluringly just out of view on the horizon, Origin had begun thinking of themselves more and more in the terms of Hollywood. The official “product development structure” that was put in place around this time by Dallas Snell demanded an executive producer, a producer, an assistant producer, a director, an assistant director, and a lead writer for every game; of all the positions on the upper rungs of the chart, only that of lead artist and lead programmer wouldn’t have been listed in the credits of a typical Hollywood film. Meanwhile Origin’s recent hire Warren Spector, who came to them with a Masters in film studies, brought his own ideas about games as interactive dramas that were less literal than Snell’s, but that would if anything prove even more of an influence on his colleagues’ developing views of just what it was Origin Systems really ought to be about. Just the previous year, Origin had released a game called Space Rogue, another of that long line of non-Ultima middling sellers, that had preceded Squadron in attempting to do Elite one better. A free-form player-directed game of space combat and trading, Space Rogue was in some ways much more ambitious than the more railroaded experience Roberts was now proposing. Yet there was little question of which game fit better with the current zeitgeist at Origin.

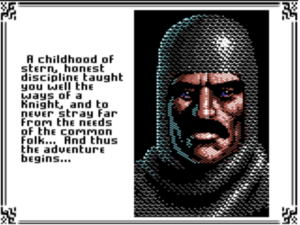

All of which does much to explain the warm reception accorded to Squadron when Chris Roberts, with Bad Blood finally off his plate, pitched it to Origin’s management formally in very early 1990. Thanks to all those moonlighting hours — as well as, one suspects, more than a few regular working hours — Roberts already had a 3D space-combat game that looked and played pretty great. A year or two earlier, that likely would have been that; Origin would have simply polished it up a little and shipped it. But now Roberts had the vision of building a movie around the game. Between flying a series of scripted missions, you would get to know your fellow pilots and follow the progress of a larger war between humanity and the Kilrathi, a race of savage cats in space.

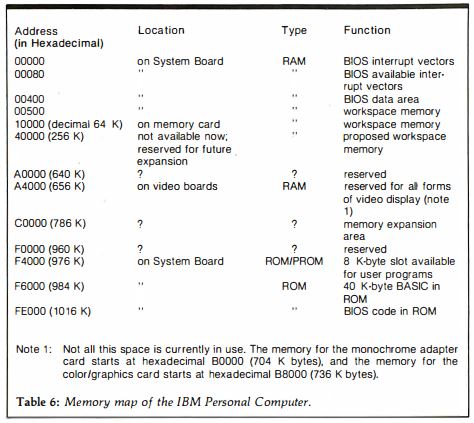

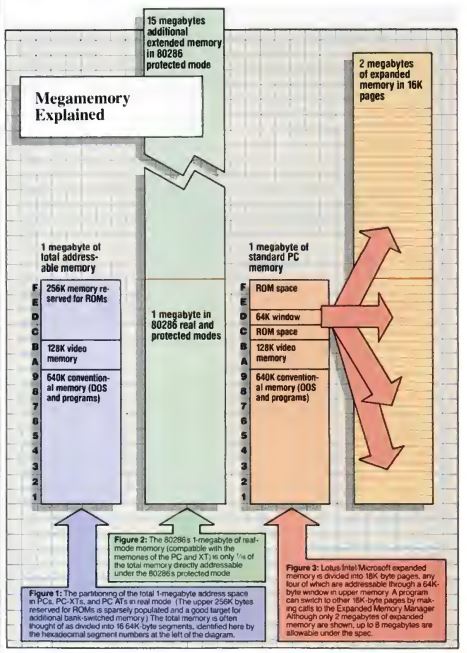

Having finally made the hard decision to abandon the 8-bit market at the beginning of 1989, Origin was now pushing aggressively in the opposite direction from their old technological conservatism, being determined to create games that showed what the very latest MS-DOS machines could really do. Like Sierra before them, they had decided that if the only way to advance the technological state of the art among ordinary consumers was to release games whose hardware requirements were ahead of the curve — a reversal of the usual approach among game publishers, who had heretofore almost universally gone where the largest existing user base already was — then that’s what they would do. Squadron could become the first full expression of this new philosophy, being unapologetically designed to run well only on a cutting-edge 80386-based machine. In what would be a first for the industry, Chris Roberts even proposed demanding expanded memory beyond the traditional 640 K for the full audiovisual experience. For Roberts, stepping up from a Commodore 64, it was a major philosophical shift indeed. “Sod this, trying to make it work for the lowest common denominator—I’m just going to try and push it,” he said, and Origin was happy to hear it.

Ultima VI had just been completed, freeing personnel for another major project. Suspecting that Squadron might be the marketplace game changer he had sought for so long for Origin, Robert Garriott ordered a full-court press in March of 1990. He wanted his people to help Chris Roberts build his movie around his game, and he wanted them to do it in less than three months. They should have a preview ready to go for the Summer Consumer Electronics Show at the beginning of June, with the final product to ship very shortly thereafter.

Responsibility for the movie’s script was handed to Jeff George, one of the first of a number of fellow alumni of the Austin tabletop-game publisher Steve Jackson Games who followed Warren Spector to Origin. George was the first Origin employee hired explicitly to fill the role of “writer.” This development, also attributable largely to the influence of Spector, would have a major impact on Origin’s future games.

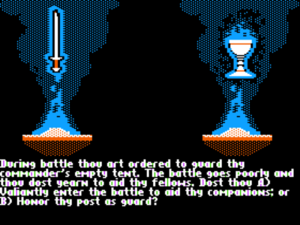

Obviously inspired by the ethical quandaries the Ultima series had become so known for over its last few installments, Chris Roberts had imagined a similarly gray-shaded world for his game, with scenarios that would cause the player to question whether the human empire she was fighting for was really any better than that of the Kilrathi. But George, to once again frame the issue in terms Roberts would have appreciated, pushed the game’s fiction toward the clear-cut good guys and bad guys of Star Wars, away from the more complicated moral universe of Star Trek. All talk of a human “empire,” for one thing, would have to go; everyone at Origin knew what their players thought of first when they thought of empires in space. Jeff George:

In the context of a space opera, empire had a bad connotation that would make people think they were fighting for the bad guys. The biggest influence I had on the story was to make it a little more black and white, where Chris had envisioned something grittier, with more shades of gray. I didn’t want people to worry about moral dilemmas while they were flying missions. That’s part of why it worked so well. You knew what you were doing, and knew why you were doing it. The good guys were really good, the bad guys were really bad.

The decision to simplify the political situation and sand away the thorny moral dilemmas demonstrates, paradoxical though it may first seem, a more sophisticated approach to narrative rather than the opposite. Some interactive narratives, like some non-interactive ones, are suited to exploring moral ambiguity. In others, though, the player just wants to fight the bad guys. While one can certainly argue that gaming has historically had far too many of the latter type and far too few of the former, there nevertheless remains an art to deciding which games are best suited for which.

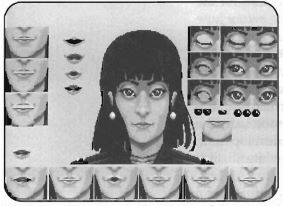

Five more programmers and four more artists would eventually join what had been Chris Roberts and Denis Loubet’s little two-man band. With the timetable so tight, the artists were left to improvise large chunks of the narrative along with the game’s visuals. By imagining and drawing the “talking head” portraits of the various other pilots with which the player would interact, artist Glen Johnson wound up playing almost as big a role as Jeff George in crafting the fictional context for the game’s dogfights in space. Johnson:

I worked on paper first, producing eleven black-and-white illustrations. In most games, I would work from a written description of the character’s likes, dislikes, and personality. In this case, I just came up with the characters out of thin air, although I realized they wanted a mixture of men and women pilots. I assigned a call sign to each portrait.

Despite the lack of time at their disposal, the artists were determined to fit the movements of the characters’ mouths to the words of dialog that appeared on the screen, using techniques dating back to classic Disney animation. Said techniques demanded that all dialog be translated into its phonetic equivalent, something that could only be done by hand. Soon seemingly half the company was doing these translations during snatches of free time. Given that many or most players never even noticed the synchronized speech in the finished game, whether it was all worth it is perhaps a valid question, but the determination to go that extra mile in this regard does say much about the project’s priorities.

The music wound up being farmed out to a tiny studio specializing in videogame audio, one of vanishingly few of its kind at the time, which was run by a garrulous fellow named George Sanger, better known as “The Fat Man.” (No, he wasn’t terribly corpulent; that was sort of the joke.) Ever true to his influences, Chris Roberts’s brief to Sanger was to deliver something “between Star Wars and Star Trek: The Motion Picture.” Sanger and his deputy Dave Govett delivered in spades. Hugely derivative of John Williams’s work though the soundtrack was — at times it threatens to segue right into Williams’s famous Star Wars theme — it contributed hugely to the cinematic feel of the game. Origin was particularly proud of the music that played in the background when the player was actually flying in space; the various themes ebbed and swelled dynamically in response to the events taking place on the computer screen. It wasn’t quite the first time anyone had done something like this in a game, but no one had ever managed to do it in quite this sophisticated a way.

The guiding theme of the project remained the determination to create an embodied experience for the player. Chris Roberts cites the interactive movies of Cinemaware, which could be seen as the prototypes for the sort of game he was now trying to perfect, as huge influences in this respect as in many others. Roberts:

I didn’t want anything that made you sort of… pulled you out of being in this world. I didn’t want that typical game UI, or “Here’s how many lives you’ve got, here’s what high score you’ve got.” I always felt that broke the immersion. If you wanted to save the game you’d go to the barracks and you’d click on the bunk. If you wanted to exit, you’d click on the airlock. It was all meant to be in that world and so that was what the drive was. I love story and narrative and I think you can use that story and narrative to tie your action together and that will give your action meaning and context in a game. That was my idea and that was what really drove what I was doing.

The approach extended to the game’s manual. Harking back to the beloved scene-setting packaging of Infocom, the manual, which was written by freelancer Aaron Allston, took the form of Claw Marks, “The Onboard Magazine of TCS Tiger’s Claw” — the Tiger’s Claw being the name of the spaceborne aircraft carrier from which the player would be flying all of the missions. Like the artists, Allston would wind up almost inadvertently creating vital pieces of the game as a byproduct of the compressed schedule. “I couldn’t really determine everything at that point in development,” he remembers, “so, in some cases, specifically for the tactics information, we made some of it up and then retrofitted it and adjusted the code in the game to make it work.”

Once again in the spirit of creating a cohesive, embodied experience for the player, Roberts wanted to get away from the save-and-restore dance that was so typical of ludic narratives of the era. Therefore, instead of structuring the game’s 40 missions as a win-or-go-home linear stream, he created a branching mission tree in which the player’s course through the narrative would be dictated by her own performance. There would, in other words, be no way to definitively lose other than by getting killed. Roberts would always beg players to play the game “honestly,” beg them not to reload and replay each mission until they flew it perfectly. Only in this way would they get the experience he had intended for them to have.

As the man responsible for tying all of the elements together to create the final experience, Roberts bore the titles of director and producer under Origin’s new cinematic nomenclature. He worked under the watchful eye of Squadron‘s co-producer Warren Spector, who, being older and in certain respects wiser, was equipped to handle the day-to-day administrative tasks that Roberts wasn’t. Spector:

When I came on as producer, Chris was really focused on the direction he wanted to take with the game. He knew exactly where he was going, and it would have been hard to deflect him from that course. It would have been crazy to even want to, so Chris and I co-produced the game. Where his talent dropped out, mine started, and vice versa. We did a task breakdown, and I ended up updating, adjusting, and tracking scheduling and preparing all the documentation. He handled the creative and qualitative issues. We both juggled the resources.

In implying that his own talent “dropped out” when it came to creative issues, Spector is selling himself about a million dollars short. He was a whirling dervish of creative energy throughout the seven years he spent with Origin, if anything even more responsible than Richard Garriott for the work that came out of the company under the Ultima label during this, the franchise’s most prolific period. But another of the virtues which allowed him to leave such a mark on the company was an ability to back off, to defer to the creative visions of others when it was appropriate. Recognizing that no one knew Chris Roberts’s vision like Chris Roberts, he was content in the case of Squadron to act strictly as the facilitator of that vision. In other words, he wasn’t too proud to just play the role of organizer when it was appropriate.

Still, it became clear early on that no combination of good organization and long hours would allow Squadron to ship in June. The timetable slipped to an end-of-September ship date, perfect to capitalize on the Christmas rush.

Although Squadron wouldn’t ship in June, the Summer Consumer Electronics Show loomed with as much importance as ever as a chance to show off the game-to-be and to drum up excitement that might finally end the sniggering about Ultima Systems. Just before the big show, Origin’s lawyers delivered the sad news that calling the game Squadron would be a bad idea thanks to some existing trademarks on the name. After several meetings, Wingleader emerged as the consensus choice for a new name, narrowly beating out Wing Commander. It was thus under the former title that the world at large got its first glimpse of what would turn into one of computer gaming’s most iconic franchises. Martin Davies, Origin’s Vice President of Sales:

I kicked hard to have a demo completed for the show. It was just a gut reaction, but I knew I needed to flood retail and distribution channels with the demo. Before the release of the game, I wanted the excitement to grow so that the confidence level would be extremely high. If we could get consumers beating a path in and out of the door, asking whether the game was out, distribution would respond.

With Wingleader still just a bunch of art and sound assets not yet wired up to the core game they were meant to complement, an interactive demo was impossible. Instead Chris Roberts put together a demo on videotape, alternating clips of the battles in space with clips of whatever other audiovisual elements he could assemble from what the artists and composers had managed to complete. Origin brought a big screen and a booming sound system out to Chicago for the show; the latter prompted constant complaints from other exhibitors. The noise pollution was perfect for showing the world that there was now more to Origin Systems than intricate quests and ethical dilemmas — that they could do aesthetic maximalism as well as anyone in their industry, pushing all of the latest hardware to its absolute limit in the process. It was a remarkable transformation for a company that just eighteen months before had been doing all development on the humble little 8-bit Apple II and Commodore 64. Cobbled together though it was, the Wingleader demo created a sensation at CES.

Indeed, one can hardly imagine a better demonstration of how the computer-game industry as a whole was changing than the game that had once been known as Squadron, was now known as Wingleader, and would soon go onto fame as Wing Commander. In my next article, I’ll tell the story of how the game would come to be finished and sold, along with the even more important story of what it would mean for the future of digital entertainment.

(Sources: the books Wing Commander I and II: The Ultimate Strategy Guide by Mike Harrison and Game Design Theory and Practice by Richard Rouse III; Retro Gamer 59 and 123; Questbusters of July 1989, August 1990, and April 1991; Computer Gaming World of September 1989 and November 1992; Amiga Computing of December 1988. Online sources include documents hosted at the Wing Commander Combat Information Center, US Gamer‘s profile of Chris Roberts, The Escapist‘s history of Wing Commander, Paul Dean’s interview with Chris Roberts, and Matt Barton’s interview with George “The Fat Man” Sanger. Last but far from least, my thanks to John Miles for corresponding with me via email about his time at Origin, and my thanks to Casey Muratori for putting me in touch with him.

Wing Commander I and II can be purchased in a package together with all of their expansion packs from GOG.com.)