Where should we mark the beginning of the full-motion-video era, that most extended of blind alleys in the history of the American games industry? The day in the spring of 1990 that Ken Williams, founder and president of Sierra On-Line, wrote his latest editorial for his company’s seasonal newsletter might be as good a point as any. In his editorial, Williams coined the term “talkies” in reference to an upcoming generation of games which would have “real character voices and no text.” The term was, of course, a callback to the Hollywood of circa 1930, when sound began to come to the heretofore silent medium of film. Computer games, Williams said, stood on the verge of a leap that would be every bit as transformative, in terms not only of creativity but of profitability: “How big would the film industry be today if not for this step?”

According to Williams, the voice-acted, CD-based version of Sierra’s King’s Quest V was to become the games industry’s The Jazz Singer. But voice acting wasn’t the only form of acting which the games of the next few years had in store. A second transformative leap, comparable to that made by Hollywood when film went from black and white to color, was also waiting in the wings to burst onto the stage just a little bit later than the first talkies. Soon, game players would be able to watch real, human actors right there on their monitor screens.

As regular readers of this site probably know already, the games industry’s Hollywood obsession goes back a long way. In 1982, Sierra was already advertising their text adventure Time Zone with what looked like a classic “coming attractions” poster; in 1986, Cinemaware was founded with the explicit goal of making “interactive movies.” Still, the conventional wisdom inside the industry by the early 1990s had shifted subtly away from such earlier attempts to make games that merely played like movies. The idea was now that the two forms of media would truly become one — that games and movies would literally merge. “Sierra is part of the entertainment industry — not the computer industry,” wrote Williams in his editorial. “I always think of books, records, films, and then interactive films.” These categories defined a continuum of increasingly “hot,” increasingly immersive forms of media. The last listed there, the most immersive medium of all, was now on the cusp of realization. How many people would choose to watch a non-interactive film when they had the opportunity to steer the course of the plot for themselves? Probably about as many as still preferred books to movies.

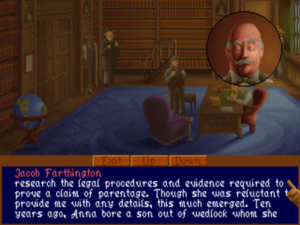

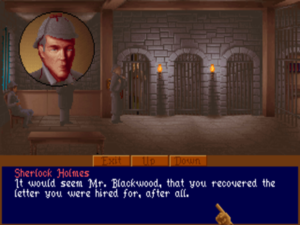

Not all that long after Williams’s editorial, the era of the full-motion-video game began in earnest. The first really prominent exemplar of the species was ICOM Simulations’s Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective series in 1992, which sent you wandering around Victorian London collecting clues to a mystery from the video snippets that played every time you visited a relevant location. The first volume of this series alone would eventually sell 1 million copies as an early CD-ROM showcase title. The following year brought Return to Zork, The 7th Guest, and Myst as three of the five biggest games of the year; all three of these used full-motion video to a greater or lesser extent. (Myst used it considerably less than the other two, and, perhaps not coincidentally, is the member of the trio that holds up by far the best today.) With success stories like those to look to, the floodgates truly opened in 1994. Suddenly every game-development project — by no means only adventure games — was looking for ways to shoehorn live actors into the proceedings.

But only a few of the full-motion-video games that followed would post anything like the numbers of the aforementioned four games. That hard fact, combined with a technological counter-revolution in the form of 3D graphics, would finally force a reckoning with the cognitive dissonance of trying to build a satisfying interactive experience by mixing and matching snippets of nonmalleable video. By 1997, the full-motion-video era was all but over. Today, few things date a game more instantly to a certain window of time than grainy video of terrible actors flickering over a background of computer-generated graphics. What on earth were people thinking?

Most full-motion-video games are indeed dire, but they’re going to be with us for quite some time to come as we continue to work our way through this history. I wish I could say that Activision’s Return to Zork, my real topic for today, was one of the exceptions to the rule of direness. Sadly, though, it isn’t.

In fact, let me be clear right now: Return to Zork is a terrible adventure game. Under no circumstances should you play it, unless to satisfy historical curiosity or as a source of ironic amusement in the grand tradition of Ed Wood. And even in these special cases, you should take care to play it with a walkthrough in hand. To do anything else is sheer masochism; you’re almost guaranteed to lock yourself out of victory within the first ten minutes, and almost guaranteed not to realize it until many hours later. There’s really no point in mincing words here: Return to Zork is one of the absolute worst adventure-game designs I’ve ever seen — and, believe me, I’ve seen quite a few bad ones.

Its one saving grace, however, is that it’s terrible in a somewhat different way from the majority of terrible full-motion-video adventure games. Most of them are utterly bereft of ideas beyond the questionable one at their core: that of somehow making a game out of static video snippets. You can almost see the wheels turning desperately in the designers’ heads as they’re suddenly confronted with the realization that, in addition to playing videos, they have to give the player something to actually do. Return to Zork, on the other hand, is chock full of ideas for improving upon the standard graphic-adventure interface in ways that, on the surface at any rate, allow more rather than less flexibility and interactivity. Likewise, even the trendy use of full-motion video, which dates it so indelibly to the mid-1990s, is much more calculated than the norm among its contemporaries.

Unfortunately, all of its ideas are undone by a complete disinterest in the fundamentals of game design on the part of the novelty-seeking technologists who created it. And so here we are, stuck with a terrible game in spite of it all. If I can’t quite call Return to Zork a noble failure — as we’ll see, one of its creators’ stated reasons for making it so callously unfair is anything but noble — I can at least convince myself to call it an interesting one.

When Activision decided to make their follow-up to the quickie cash-in Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2 a more earnest, better funded stab at a sequel to a beloved Infocom game, it seemed logical to find themselves a real Infocom Implementor to design the thing. They thus asked Steve Meretzky, whom they had just worked with on Leather Goddesses 2, if he’d like to design a new Zork game for them as well. But Meretzky hadn’t overly enjoyed trying to corral Activision’s opinionated in-house developers from a continent away last time around; this time, he turned them down flat.

Meretzky’s rejection left Activision without a lot of options to choose from when it came to former Imps. A number of them had left the games industry upon Infocom’s shuttering three years before, while, of those that remained, Marc Blank, Mike Berlyn, Brian Moriarty, and Bob Bates were all employed by one of Activison’s direct competitors. Activision therefore turned to Doug Barnett, a freelance artist and designer who had been active in the industry for the better part of a decade; his most high-profile design gig to date had been Cinemaware’s Lords of the Rising Sun. But he had never designed a traditional puzzle-oriented adventure game, as one can perhaps see all too well in the game that would result from his partnership with Activision. He also didn’t seem to have a great deal of natural affinity for Zork. In the lengthy set of notes and correspondence relating to the game’s development which has been put online by The Zork Library, a constant early theme on Activision’s part is the design’s lack of “Zorkiness.” “As it stands, the design constitutes more of a separate and unrelated story, rather than a sequel to the Zork series,” they wrote at one point. “It was noted that ‘Zork’ is the name of a vast ancient underground empire, yet Return to Zork takes place in a mostly above-ground environment.”

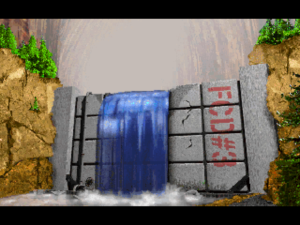

In fairness to Barnett, Zork had always been more of a state of mind than a coherent place. With the notable exception of Steve Meretzky, everyone at Infocom had been wary of overthinking a milieu that had originally been plucked out of the air more or less at random. In comparison to other shared worlds — even other early computer-game worlds, such as the Britannia of Richard Garriott’s Ultima series — there was surprisingly little there there when it came Zork: no well-established geography, no well-established history which everybody knew — and, most significantly of all, no really iconic characters which simply had to be included. At bottom, Zork boiled down to little more than a modest grab bag of tropes which lived largely in the eye of the beholder: the white house with a mailbox, grues, Flood Control Dam #3, Dimwit Flathead, the Great Underground Empire itself. And even most of these had their origin stories in the practical needs of an adventure game rather than any higher world-building purpose. (The Great Underground Empire, for example, was first conceived as an abandoned place not for any literary effect but because living characters are hard to implement in an adventure game, while the detritus they leave behind is relatively easy.)

That said, there was a distinct tone to Zork, which was easier to spot than it was to describe or to capture. Barnett’s design missed this tone, even as it began with the gleefully anachronistic, seemingly thoroughly Zorkian premise of casting the player as a sweepstakes winner on an all-expenses-paid trip to the idyllic Valley of the Sparrows, only to discover it has turned into the Valley of the Vultures under the influence of some pernicious, magical evil. Barnett and Activision would continue to labor mightily to make Return to Zork feel like Zork, but would never quite get there.

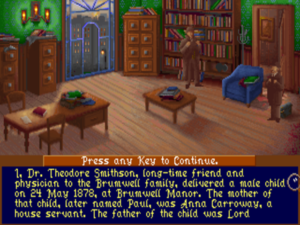

By the summer of 1992, Barnett’s design document had already gone through several revisions without entirely meeting Activision’s expectations. At this point, they hired one Eddie Dombrower to take personal charge of the project in the role of producer. Like Barnett, Dombrower had been working in the industry for quite some time, but had never worked on an adventure game; he was best known for World Series Major League Baseball on the old Intellivision console and Earl Weaver Baseball on computers. Dombrower gave the events of Return to Zork an explicit place in Zorkian history — some 700 years after Infocom’s Beyond Zork — and moved a big chunk of the game underground to remedy one of his boss’s most oft-repeated objections to the existing design.

More ominously, he also made a comprehensive effort to complicate Barnett’s puzzles, based on feedback from players and reviewers of Leather Goddesses 2, who were decidedly unimpressed with that game’s simple-almost-to-the-point-of-nonexistence puzzles. The result would be the mother of all over-corrections — a topic we’ll return to later.

Unlike Leather Goddesses 2, whose multimedia ambitions had led it to fill a well-nigh absurd 17 floppy disks, Return to Zork had been planned almost from its inception as a product for CD-ROM, a technology which, after years of false promises and setbacks, finally seemed to be moving toward a critical mass of consumer uptake. In 1992, full-motion video, CD-ROM, and multimedia computing in general were all but inseparable concepts in the industry’s collective mind. Activision thus became one of the first studios to hire a director and actors and rent time on a sound stage; the business of making computer games had now come to involve making movies as well. They even hired a professional Hollywood screenwriter to punch up the dialog and make it more “cinematic.”

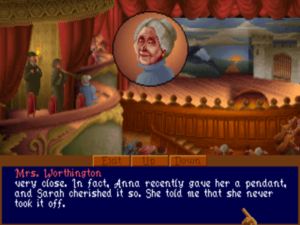

In general, though, while the computer-games industry was eager to pursue a merger with Hollywood, the latter was proving far more skeptical. There was still little money in computer games in comparison with movies, and there was very little prestige — rather the opposite, most would say — in “starring” in a game. The actors whom games could manage to attract were therefore B-listers at best. Return to Zork actually collected a more accomplished — or at least more high-profile — cast than most. Among them were Ernie Lively, a veteran supporting player from television shows such as The Dukes of Hazzard; his daughter Robyn Lively, fresh off a six-episode stint as a minor character on David Lynch’s prestigious critics’ darling Twin Peaks; Jason Hervey, who was still playing older brother Wayne on the long-running coming-of-age sitcom The Wonder Years; and Sam Jones, whose big shot at leading-man status had come with the film Flash Gordon back in 1980 and gone with its mixed reception.

If the end result would prove less than Oscar-worthy, it’s for the most part not cringe-worthy either. After all, the cast did consist entirely of acting professionals, which is more than one can say for many productions of this ilk — and certainly more than one can say for the truly dreadful voice acting in Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2, Activision’s previous attempt at a multimedia adventure game. While they were hampered by the sheer unfamiliarity of talking directly “to” the invisible player of the game — as Ernie Lively put it, “there’s no one to act off of” — they did a decent job with the slight material they had to work with.

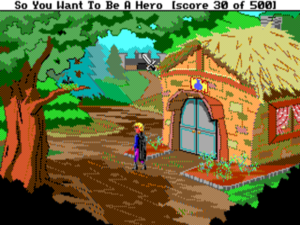

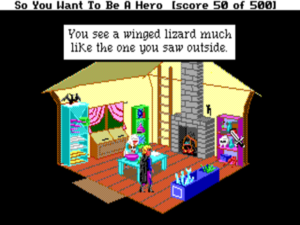

The fact that they were talking to the player rather than acting out scenes with one another actually speaks to a degree of judiciousness in the use of full-motion video on Activision’s part. Rather than attempting to make an interactive movie in the most literal sense — by having a bunch of actors, one of them representing the protagonist, act out each of the player’s choices — Activision went for a more thoughtful mixed-media approach that could, theoretically anyway, eliminate most of the weaknesses of the typical full-motion-video adventure game. For the most part, only conversations involved the use of full-motion video; everything else was rendered by Activision’s pixel artists and 3D modelers in conventional computer graphics. The protagonist wasn’t shown at all: at a time when the third-person view was the all but universal norm in adventure games, Activision opted for a first-person view.

The debate over whether an adventure-game protagonist ought to be a blank slate which the player can fill with her own personality or an established character which the player merely guides and empathizes with was a longstanding one even at the time when Return to Zork was being made. Certainly Infocom had held rousing internal debates on the subject, and had experimented fairly extensively with pre-established protagonists in some of their games. (These experiments sometimes led to rousing external debates among their fans, most notably in the case of the extensively characterized and tragically flawed protagonist of Infidel, who meets a nasty if richly deserved end no matter what the player does.) The Zork series, however, stemmed from an earlier, simpler time in adventure games than the rest of the Infocom catalog, and the “nameless, faceless adventurer,” functioning as a stand-in for the player herself, had always been its star. Thus Activision’s decision not to show the player’s character in Return to Zork, or indeed to characterize her in any way whatsoever, is a considered one, in keeping with everything that came before.

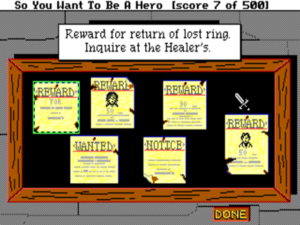

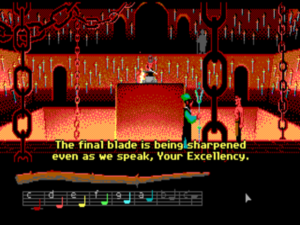

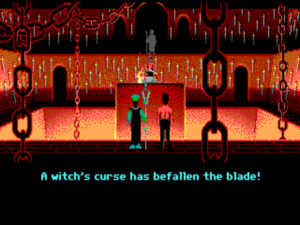

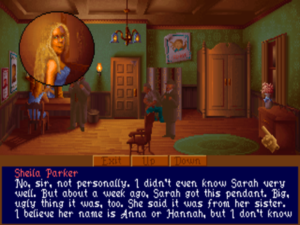

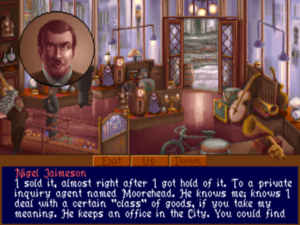

In fact, the protagonist of Return to Zork never actually says anything. To get around the need, Activision came up with a unique attitude-based conversation engine. As you “talk” to other characters, you choose from three stances — threatening, interested, or bored — and listen only to your interlocutors’ reactions. Not only does your own dialog go unvoiced, but you don’t even see the exact words you use; the game instead lets you imagine your own words. Specific questions you might wish to ask are cleverly turned into concrete physical interactions, something games do much better than abstract conversations. As you explore, you have a camera with which to take pictures of points of interest. During conversations, you can show the entries from your photo album to your interlocutor, perhaps prompting a reaction. You can do the same with objects in your inventory, locations on the auto-map you always carry with you, or even the tape recordings you automatically make of each interaction with each character.

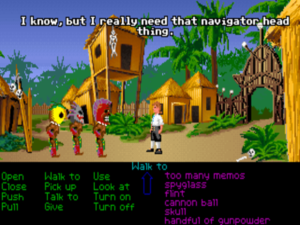

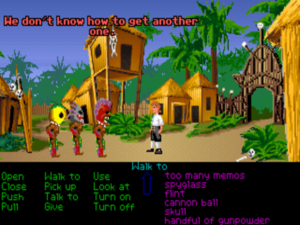

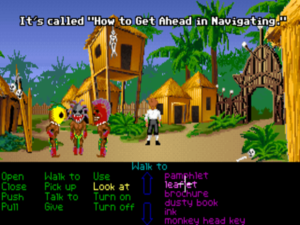

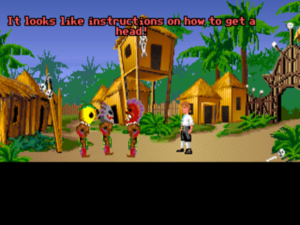

So, whatever else you can say about it, Return to Zork is hardly bereft of ideas. William Volk, the technical leader of the project, was well up on the latest research into interface design being conducted inside universities like MIT and at companies like Apple. Many such studies had concluded that, in place of static onscreen menus and buttons, the interface should ideally pop into existence just where and when the user needed it. The result of such thinking in Return to Zork is a screen with no static interface at all; it instead pops up when you click on an object with which you can interact. Since it doesn’t need the onscreen menu of “verbs” typical of contemporaneous Sierra and LucasArts adventure games, Return to Zork can give over the entirety of the screen to its graphical portrayal of the world.

In addition to being a method of recapturing screen real estate, the interface was conceived as a way to recapture some of the sense of boundless freedom which is such a characteristic of parser-driven text adventures — a sense which can all too easily become lost amidst the more constrained interfaces of their graphical equivalent. William Volk liked to call Return to Zork‘s interface a “reverse parser”: clicking on a “noun” in the environment or in your inventory yields a pop-up menu of “verbs” that pertain to it. Taking an object in your “hand” and clicking it on another one yields still more options, the equivalent of commands to a parser involving indirect as well as direct objects. In the first screen of the game, for example, clicking the knife on a vulture gives options to “show knife to vulture,” “throw knife at vulture,” “stab vulture with knife,” or “hit vulture with knife.” There are limits to the sense of possibility: every action had to be anticipated and hand-coded by the development team, and most of them are the wrong approach to whatever you’re trying to accomplish. In fact, in the case of the example just mentioned as well as many others, most of the available options will get you killed; Return to Zork loves instant deaths even more than the average Sierra game. And there are many cases of that well-known adventure-game syndrome where a perfectly reasonable solution to a problem isn’t implemented, forcing you to devise some absurdly convoluted solution that is implemented in its stead. Still, in a world where adventure games were getting steadily less rather than more ambitious in their scope of interactive possibility — to a large extent due to the limitations of full-motion video — Return to Zork was a welcome departure from the norm, a graphic adventure that at least tried to recapture the sense of open-ended possibility of an Infocom game.

Indeed, there are enough good ideas in Return to Zork that one really, really wishes they all could have been tied to a better game. But sadly, I have to stop praising Return to Zork now and start condemning it.

The most obvious if perhaps most forgivable of its sins is that, as already noted, it never really manages to feel like Zork — not, at least, like the classic Zork of the original trilogy. (Steve Meretzky’s Zork Zero, Infocom’s final release to bear the name, actually does share some of the slapstick qualities of Return to Zork, but likewise rather misses the feel of the original.) The most effective homage comes at the very beginning, when the iconic opening text of Zork I appears onscreen and morphs into the new game’s splashy opening credits. It’s hard to imagine a better depiction circa 1993 of where computer gaming had been and where it was going — which was, of course, exactly the effect the designers intended.

Once the game proper gets under way, however, modernity begins to feel much less friendly to the Zorkian aesthetic of old. Most of Zork‘s limited selection of physical icons do show up here, from grues to Flood Control Dam #3, but none of it feels all that convincingly Zork-like. The dam is a particular disappointment; what was described in terms perfect for inspiring awed flights of the imagination in Zork I looks dull and underwhelming when portrayed in the cruder medium of graphics. Meanwhile the jokey, sitcom-style dialog that confronts you at every turn feels even less like the original trilogy’s slyer, subtler humor.

This isn’t to say that Return to Zork‘s humor doesn’t connect on occasion. It’s just… different from that of Dave Lebling and Marc Blank. By far the most memorable character, whose catchphrase has lived on to this day as a minor Internet meme, is the drunken miller named Boos Miller. (Again, subtlety isn’t this game’s trademark.) He plies you endlessly with whiskey, whilst repeating, “Want some rye? Course you do!” over and over and over in his cornpone accent. It’s completely stupid — but, I must admit, it’s also pretty darn funny; Boos Miller is the one thing everyone who ever played the game still seems to remember about Return to Zork. But, funny though he is, he would be unimaginable in any previous Zork.

Of course, a lack of sufficient Zorkiness need not have been the kiss of death for Return to Zork as an adventure game in the abstract. What really does it in is its thoroughly unfair puzzle design. This game plays like the fever dream of a person who hates and fears adventure games. It’s hard to know where to even start (or end) with this cornucopia of bad puzzles, but I’ll describe a few of them, ranked roughly in order of their objectionability.

The Questionable: At one point, you find yourself needing to milk a cow, but she won’t let you do so with cold hands. Do you need to do something sensible, like, say, find some gloves or wrap your hands in a blanket? Of course not! The solution is to light some of the hay that’s scattered all over the wooden barn on fire and warm your hands that way. For some reason, the whole place doesn’t go up in smoke. This solution is made still more difficult to discover by the way that the game usually kills you every time you look at it wrong. Why on earth would it not kill you for a monumentally stupid act like this one? To further complicate matters, for reasons that are obscure at best you can only light the hay on fire if you first pick it up and then drop it again. Thus even many players who are consciously attempting the correct solution will still get stuck here.

The Absurd: At another point, you find a bra. You have to throw it into an incinerator in order to get a wire out of it whose existence you were never aware of in the first place. How does the game expect you to guess that you should take such an action? Apparently some tenuous linkage with the 1960s tradition of bra burning and, as a justification after the fact, the verb “to hot-wire.” Needless to say, throwing anything else into the incinerator just destroys the object and, more likely than not, locks you out of victory.

The Incomprehensible: There’s a water wheel out back of Boos’s house with a chock holding it still. If you’ve taken the chock and thus the wheel is spinning, and you’ve solved another puzzle that involves drinking Boos under the table (see the video above), a trapdoor is revealed in the floor. But if the chock is in place, the trapdoor can’t be seen. Why? I have absolutely no idea.

The Brutal: In a way, everything you really need to know about Return to Zork can be summed up by its most infamous single puzzle. On the very first screen of the game, there’s a “bonding plant” growing. If you simply pull up the plant and take it with you, everything seems fine — until many hours later, when you finally find a use for the plant you’ve been carting around all this time. Great!, you think. But it turns out that you need a living version of it; you were supposed to have used a knife to dig up the plant rather than pulling or cutting it. Technically speaking, you can fix the damage you’ve done, but the method of doing so is crazy obscure; you have to eat the plant, then return to the site where you first found it, where you’ll discover that another has grown in its place. I maintain that almost nobody will figure that out without the help of a walkthrough or strategy guide.

All of the puzzles just described, and the many equally bad ones, are made still more complicated by the game’s general determination to be a right bastard to you every chance it gets. If, as Robb Sherwin once put it, the original Zork games hate their players, this game has found some existential realm beyond mere hatred. It will let you try to do many things to solve each puzzle, but, of those actions that don’t outright kill you, a fair percentage lock you out of victory in one way or another. Sometimes, as in the case of its most infamous puzzle, it lets you think you’ve solved them, only to pull the rug out from under you much later.

So, you’re perpetually on edge as you tiptoe through this minefield of instant deaths and unwinnable states; you’ll have a form of adventure-game post-traumatic-stress syndrome by the time you’re done, even if you’re largely playing from a walkthrough. The instant deaths are annoying, but nowhere near as bad as the unwinnable states; the problem there is that you never know whether you’ve already locked yourself out of victory, never know whether you can’t solve the puzzle in front of you because of something you did or didn’t do a long time ago.

It all combines to make Return to Zork one of the worst adventure games I’ve ever played. We’ve sunk to Time Zone levels of awful with this one. No human not willing to mount a methodical months-long assault on this game, trying every possibility everywhere, could possibly solve it unaided. Even the groundbreaking interface is made boring and annoying by the need to show everything to everyone and try every conversation stance on everyone, always with the lingering fear that the wrong stance could spoil your game. Adventure games are built on trust between player and designer, but you can’t trust Return to Zork any farther than you can throw it. Amidst all the hand-wringing at Activision over whether Return to Zork was or was not sufficiently Zorky, they forgot the most important single piece of the Infocom legacy: their thoroughgoing commitment to design, and the fundamental respect that commitment demonstrated to the players who spent their hard-earned money on Infocom games. “Looking back at the classics might be a good idea for today’s game designers,” wrote Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia at the conclusion of her mixed review of Return to Zork. “Good puzzle construction, logical development, and creative inspiration are in rich supply on those dusty disks.” None of these, alas, is in correspondingly good supply in Return to Zork.

The next logical question, then, is just how Return to Zork‘s puzzles wound up being so awful. After all, this game wasn’t the quickie cash grab that Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2 had been. The development team put serious thought and effort into the interface, and there were clearly a lot of people involved with this game who cared about it a great deal — among them Activision’s CEO Bobby Kotick, who was willing to invest almost $1 million to bring the whole project to fruition at a time when cash was desperately short and his creditors had him on a short leash indeed.

The answer to our question apparently comes down to the poor reception of Leather Goddesses 2, which had stung Activision badly. In an interview given shortly before Return to Zork‘s release, Eddie Dombrower said that, “based on feedback that the puzzles in Leather Goddesses of Phobos [2] were too simple,” the development team had “made the puzzles increasingly difficult just by reworking what Doug had already laid out for us.” That sounds innocent enough on the face of it. But, speaking to me recently, William Volk delivered a considerably darker variation on the same theme. “People hated Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2 — panned it,” he told me. “So, we decided to wreak revenge on the entire industry by making Return to Zork completely unfair. Everyone bitches about that title. There’s 4000 videos devoted to Return to Zork on YouTube, most of which are complaining because the title is so blatantly unfair. But, there you go. Something to pin my hat on. I made the most unfair game in history.”

For all that I appreciate Volk sharing his memories with me, I must confess that my initial reaction to this boast was shock, soon to be followed by genuine anger at the lack of empathy it demonstrates. Return to Zork didn’t “wreak revenge” on its industry, which really couldn’t have cared less. It rather wreaked “revenge,” if that’s the appropriate word, on the ordinary gamers who bought it in good faith at a substantial price, most of whom had neither bought nor commented on Leather Goddesses 2. I sincerely hope that Volk’s justification is merely a case of hyperbole after the fact. If not… well, I really don’t know what else to say about such juvenile pettiness, so symptomatic of the entitled tunnel vision of so many who are fortunate enough to work in technology, other than that it managed to leave me disliking Return to Zork even more. Some games are made out of an openhearted desire to bring people enjoyment. Others, like this one, are not.

I’d like to be able to say that Activision got their comeuppance for making Return to Zork such a bad game, demonstrating such contempt for their paying customers, and so soiling the storied Infocom name in the process. But exactly the opposite is the case. Released in late 1993, Return to Zork became one of the breakthrough titles that finally made the CD-ROM revolution a reality, whilst also carrying Activision a few more steps back from the abyss into which they’d been staring for the last few years. It reportedly sold 1 million copies in its first year — albeit the majority of them as a bundled title, included with CD-ROM drives and multimedia upgrade kits, rather than as a boxed standalone product. “Zork on a brick would sell 100,000 copies,” crowed Bobby Kotick in the aftermath.

Perhaps. But more likely not. Even within the established journals of computer gaming, whose readership probably didn’t constitute the majority of Return to Zork‘s purchasers, reviews of the game were driven more by enthusiasm for its graphics and sound, which really were impressive in their day, than by Zork nostalgia. Discussed in the euphoria following its release as the beginning of a full-blown Infocom revival, Return to Zork would instead go down in history as a vaguely embarrassing anticlimax to the real Infocom story. A sequel to Planetfall, planned as the next stage in the revival, would linger in Development Hell for years and ultimately never get finished. By the end of the 1990s, Zork as well would be a dead property in commercial terms.

Rather than having all that much to do with its Infocom heritage, Return to Zork‘s enormous commercial success came down to its catching the technological zeitgeist at just the right instant, joining Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, The 7th Guest, and Myst as the perfect flashy showpieces for CD-ROM. Its success conveyed all the wrong messages to game publishers like Activision: that multimedia glitz was everything, and that design really didn’t matter at all.

If it stings a bit that this of all games, arguably the worst one ever to bear the Infocom logo, should have sold better than any of the rest of them, we can comfort ourselves with the knowledge that Quality does have a way of winning out in the end. Today, Return to Zork is a musty relic of its time, remembered if at all only for that “want some rye?” guy. The classic Infocom text adventures, on the other hand, remain just that — widely recognized as timeless classics, their clean text-only presentations ironically much less dated than all of Return to Zork‘s oh-so-1993 multimedia flash. Justice does have a way of being served in the long run.

(Sources: the book Return to Zork Adventurer’s Guide by Steve Schwartz; Computer Gaming World of February 1993, July 1993, November 1993, and January 1994; Questbusters of December 1993; Sierra News Magazine of Spring 1990; Electronic Games of January 1994; New Media of June 24 1994. Online sources include The Zork Library‘s archive of Return to Zork design documents and correspondence, Retro Games Master‘s interview with Doug Barnett, and Matt Barton’s interview with William Volk. Some of this article is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Finally, my huge thanks to William Volk for sharing his memories and impressions with me in a personal interview.)