The early days were the best. We had successes, we had fun, and we had a good business model. As the industry changed, everything became more complicated and harder.

— Bob Bates

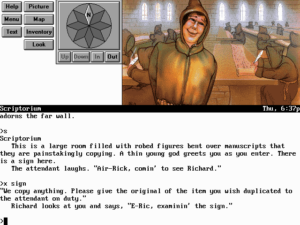

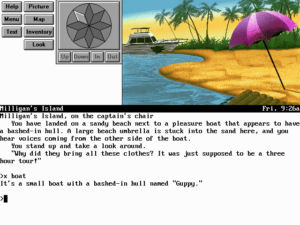

The history of Legend Entertainment can be divided into three periods. When Bob Bates and Mike Verdu first founded the company in 1989, close on the heels of Infocom’s shuttering, they explicitly envisioned it as the heir to the latter’s rich heritage. And indeed, Legend’s early games were at bottom parser-based text adventures, the last of their kind to be sold through conventional retail outlets. That said, they were a dramatic departure from the austerity of Zork: this textual lily was gilded with elaborate menus of verbs, nouns, and prepositions that made actual typing optional, along with an ever increasing quantity of illustrations, sound effects, music, eventually even cutscenes and graphical mini-games. At last, in 1993, the inevitable endpoint of all this creeping multimedia was reached. Between Gateway II: Homeworld and Companions of Xanth, the parser that had still been lurking behind it all disappeared. Thus ended the text-adventure phase of Legend’s existence and began the point-and-click-adventure phase.

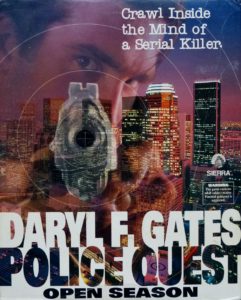

Legend continued happily down that second road for a few years. Its games in this vein weren’t as flashy or as high-profile as those of Sierra or LucasArts, but a coterie of loyal fans appreciated them for their more understated aesthetic qualities and for their commitment to good, non-frustrating design — a commitment that even LucasArts proved unable or unwilling to match as the decade wore on. Legend’s games during this period were almost universally based on licensed literary properties, which, combined with in-gaming writing that remained a cut above the norm, still allowed the company to retain some vestige of being the heir to Infocom.

By 1996, however, another endpoint seemed to be looming. One of Legend’s two games of the year before had been the biggest, most expensive production they had yet dared to undertake, as well as a rare foray into non-licensed territory. Mission Critical had been made possible by a $2.5 million investment from the book-publishing giant Random House. The game was the brainchild and the special baby of founder Mike Verdu, a space opera into which he poured his heart and soul. It filled three CDs, the first of which was mostly devoted to a bravura live-action opening movie that starred Michael Dorn, well known to legions of science-fiction fans as the Klingon Lieutenant Worf on Star Trek: The Next Generation, here taking the helm of another starship that might just as well have been the USS Enterprise. But there was more to Mission Critical than surface flash and stunt casting. It was an astonishingly ambitious production in other ways as well: from the writing and world-building (Verdu created a detailed future history for humanity to serve as the game’s backstory) to the multi-variant gameplay itself (a remarkably sophisticated real-time-strategy game is embedded into the adventure). I for one feel no hesitation in calling Mission Critical one of the best things Legend ever did.

But when it was released into a marketplace that was already glutted with superficially similar if generally inferior “Siliwood” productions, Mission Critical got lost in the shuffle. The big hit in this space in 1995 — in fact, the very last hit “interactive movie” ever — was Sierra’s Phantasmagoria, which evinced nothing like the same care for its fiction but nevertheless sold 1 million copies on the back of its seven CDs worth of canned video footage. Mission Critical, on the other hand, struggled to sell 50,000 copies, numbers which were actually slightly worse than those of Shannara, Legend’s other game of 1995, a worthy but far more modest and traditionalist adventure. The consequences to the bottom line were devastating. After hovering around the break-even point for most of its existence, Legend posted a loss for 1995 of more than $2 million, on total revenues of less than $3 million. Random House, which despite its literary veneer was perfectly capable of being as ruthless as any other titan of Corporate America, decided that it wanted out of Legend — in fact, it wanted Legend to pay it back $1 million of its investment, a demand which the fine print in the contract allowed. (Random House was certainly not making any friends in the world of nerdy media at this time; it was holding TSR, the maker of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, over another barrel.)

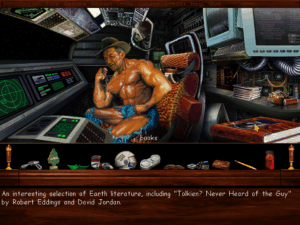

Beset by existential threats, Legend managed in 1996 to put out only one game, an even more radical departure from the norm than Mission Critical had been. Star Control 3 had the fortune or perhaps misfortune of being the sequel to 1992’s Star Control II, an unusual and much-loved amalgamation of outer-space adventure, action, and CRPG that was created by the studio Toys for Bob and published by Accolade. As it happened, Accolade also served as Legend’s distributor from 1992 to 1994. (RandomSoft, the software arm of Random House, took up that role afterward.) It was through this relationship that the Star Control 3 deal — a licensing deal of a different stripe than that to which the company had grown accustomed — came to Legend, after Toys for Bob said that they weren’t interested in making another game in the series right away. Michael Lindner, a long-serving music composer, programmer, and designer at Legend who loved Star Control II, lobbied hard with his bosses to take on Star Control 3, and was duly appointed Lead Designer once the contract was signed. Being so different from anything Legend had attempted before, the game took a good two years to complete.

Star Control 3 received good reviews from the professionals immediately after its release in September of 1996. Computer Gaming World magazine, for example, called it a “truly stellar experience” and “the ultimate space adventure,” while the website GameSpot deemed it “one of the best titles to come out this year.” It initially sold quite well on the strength of these reviews as well as its name; in fact, it became Legend’s best-selling game to date, their first to shift more than 100,000 units.

Yet once people had had some time to settle in and really play it, an ugly backlash that has never reversed itself set in. To this day, Star Control 3 remains about as popular as tuberculosis among the amazingly durable Star Control II fan base. In the eyes of many of them, it not only pales in comparison to its predecessor, but the non-involvement of the Toys for Bob crew makes it fundamentally illegitimate.

Whatever else it may be, Star Control 3 is not the purely cynical cash-grab it’s so often described as; on the contrary, it’s an earnest effort that if anything wants a little bit too badly to live up to the name on its box. And yet it’s hard to avoid the feeling when playing it that Legend has departed too much from their core competencies. The most significant addition to the Star Control II template is a new layer of colony management: you have to maintain a literal space empire in order to produce the fuel you need to send your starship out in search of the proverbial new life and new civilizations. Unfortunately, the colony game is more tedious than fun, a constant nagging distraction from what you really want to be doing. The other layers of the genre lasagna are better, but none of them is good enough to withstand a concerted comparison to Star Control II. The feel of the action-based starship combat — Legend’s first real attempt to implement a full-on action game — is subtly off, as is the interface in general. For example, a hopelessly convoluted 3D star map makes navigation ten times the chore it ought to be.

In the end, then, Star Control 3 is a case of damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Where it’s bold, it comes off as ill-considered: it represents the aliens you meet as digitized hand puppets, drawing mocking references to Sesame Street online. Where it plays it safe, it comes off as tepid: the writing — usually Legend’s greatest strength — reads like Star Control fan fiction. Still, Star Control 3 isn’t actively terrible by any means. It’s better than its rather horrendous modern reputation — but, then again, that’s not saying much, is it? There are better games out there that you could be playing, whether the date on your calendar is 1996 or 2025.

In its day, however, its strong early sales allowed Bob Bates and Mike Verdu to keep the lights on at Legend for a little while longer. A shovelware compilation of the early games called The Lost Adventures of Legend, whose name consciously echoed Activision’s surprisingly successful Lost Treasures of Infocom collections, brought in a bit more much-needed revenue for virtually no outlay.

Nevertheless, Bob Bates and Mike Verdu were by now coming to understand that securing Legend’s future in the longer term would likely require nothing less than a full-fledged reinvention of the company and its games — a far more radical overhaul than the move from a parser-based to a point-and-click interface. Everything about the games industry in the second half of the 1990s seemed to militate against a boutique studio and publisher like Legend. As the number of new games that appeared each year continued to increase, shelf space at retail was becoming ever harder to secure, even as digital distribution was at this point still a non-starter for games like those of Legend that filled hundreds of megabytes on CD. Meanwhile it was slowly becoming clear that the adventure genre had peaked in 1995 and was now sliding into a marked decline; there were no new million-selling adventure games like Phantasmagoria to be found in 1996. The games that sold best now were first-person shooters and real-time strategies, two genres that hadn’t existed back when Legend had been founded.

Mike Verdu, whose gaming palette was more diverse than that of the hardcore adventurer Bob Bates, hatched a plan to enter the 3D-shooter space. Three years on from the debut of DOOM, he sensed that John Carmack’s old formulation about the role of story in this sort of game — “Story in a game is like the story in a porn movie. It’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.” — no longer held completely true in the minds of at least some developers and players; he sensed that the world was ready for richer narratives and more coherent settings in its action games. His thinking was very much on trend: LucasArts was in the latter stages of making Jedi Knight at the time, and Valve had already embarked on Half-Life. Verdu believed that Legend might be able to apply their traditional strengths — writing, storytelling, aesthetic texture, perhaps even a smattering of adventure-style puzzle-solving — to the shooter genre with good results.

To do that, however, he and Bob Bates would need to drum up a new investor or investors, to stabilize the company’s rocky finances, pay Random House its $1 million ransom, and, last but by no means least, fund this leap into the three-dimensional unknown. As they wrote in their investor’s prospectus at this time, “Legend’s strengths in storytelling and world creation will be used to craft a unique game experience that combines combat, character interaction, exploration, and puzzle solving.” They had already secured what they thought was the perfect literary license for the experiment: the Wheel of Time novels by Robert Jordan, which were currently the best-selling epic-fantasy books in the world from an author not named J.R.R. Tolkien.

After months of beating the bushes, they found the partner they were seeking in GT Interactive, an outgrowth of a peddler of home-workout videos that had exploded onto the games industry in 1994 by publishing DOOM II exclusively to retail stores. (The original DOOM had been sold via the shareware model, with boxed distribution coming only later.) Now, GT was to be the publisher of Epic MegaGame’s Unreal, a shooter whose core technology was, so it was said, even better than id Software’s latest Quake engine. GT was able to secure the Unreal engine for Legend’s use long before the game that bore its name shipped. Even with that enormous leg-up, Legend would need every bit of their new publisher’s largess and patience; The Wheel of Time would prove a much bigger mouthful to swallow than Bob and Mike had ever anticipated, such that it wouldn’t be done until the end of 1999, more than two and a half years after the project was initiated.

As you’ve probably gathered, these events herald the beginning of the transition from the second to the third phase of Legend’s history, from Legend as a purveyor primarily of adventure games to a maker of 3D shooters that retain only scattered vestiges of the company’s past. Yet this transition wasn’t as clean or as abrupt as that from parser-driven to point-and-click adventures. While most of Legend was chasing reinvention in the last years of the 1990s, another, smaller part was sticking to what they had always done. There would come two more traditionalist adventure games before The Wheel of Time made it out the door to signal to the world that Legend Entertainment had become a very different sort of games studio.

So, we’ll save The Wheel of Time and what came after for a later article. I’d like to use the rest of this one to look at that those last two purist adventures from Legend.

Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon is one of those games that I would love to love much more than I actually do. It’s warm-hearted and well-meaning and wants nothing more than to show me a good time. Unfortunately, it mostly just bores me. In all of these respects, it has much in common with its literary source material.

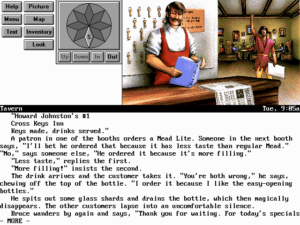

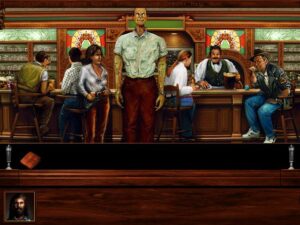

Said source is the Callahan’s series by the science-fiction journeyman Spider Robinson, the first volume of which shares its name with the game. Born in the 1970s as loosely linked short stories in the pages of Analog magazine, it’s written science fiction’s nearest equivalent to the television sitcom Cheers; the stories all revolve around a convivial bar where everybody knows your name, owned and operated by a fellow named Mike Callahan in lieu of Sam Malone. The tone is what we like to call hyggelig here in Denmark: cozy and welcoming, both for the patrons of the bar and for the reader. A sign that Mike Callahan keeps hanging on the wall behind his post says it all: “Shared pain is lessened; shared joy is increased.” The stories manage to qualify as science fiction — or maybe a better description is urban fantasy? — by including elements of the inexplicable and paranormal: aliens drop in for a drink, as do time travelers, a talking dog, and plenty of other freaks and oddities. If you read long enough, you will begin to realize that Mike Callahan himself is not quite what he appears to be. But never fear, he’s still a good guy for all that.

It’s very hard even for a curmudgeon like me to work up any active dislike for a series that so plainly just wants to make us feel good. And yet I must admit that I’ve never been able to work up the will to read beyond the first book either. Even when I first encountered Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon in the stacks of my local library at the ripe old age of twelve or so, it felt so slight and contrived that I couldn’t be bothered to finish it. When I picked the first book up again as part of my due diligence for writing this article, I wound up feeling precisely the same way, thus illustrating that I either had exceptionally good taste as a twelve-year-old or that I am a sad case of arrested development. (The child is the father to the man, as they say.)

Still, none of this need be the kiss of death for the game. I’ve played a fair number of games, from Legend and others, that are based on books that I would never choose to read on my own, and enjoyed a surprising number of them. But, as I noted at the outset, the game of Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon isn’t in this group.

Callahan’s was the second Legend adventure game to be masterminded by a former Sierra designer, after Shannara, by Corey and Lori Ann Cole of Quest for Glory fame. This time up, we have Josh Mandel, a former standup comedian who had once been a regular on the same circuit as such future stars as David Letterman, Jay Leno, and Jerry Seinfeld. His own life took a very different course when a close encounter with Leisure Suit Larry in the Land of the Lounge Lizards caused him to seek a job with the company that had made it. His design credits at Sierra included Pepper’s Adventures in Time, Freddy Pharkas: Frontier Pharmacist, and Space Quest 6: The Spinal Frontier. Having left Sierra in the middle of the Space Quest 6 project because he was unhappy with the company’s direction, he was available for Legend to sign to a design contract circa late 1995.

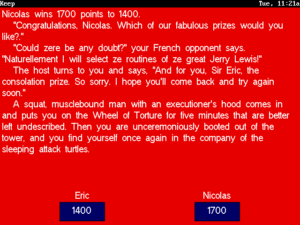

Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon is a very well-made game by any objective standard. The graphics and sound, created by a stable of out-of-house free agents to whom Legend returned again and again, are attractive and polished and perfectly in tune with the personality of the books. If the overriding standard by which you judge this game is how well it evokes its source material, it can only be counted a rousing success. Hewing to the series’ roots as a collection of short stories rather than anything so ambitious as a novel, the game uses Callahan’s Bar as a jumping-off point for half a dozen largely self-contained vignettes, which take you everywhere from Manhattan to Brazil, from outer space to Transylvania. (Yes, there is a vampire.)

The worst objective complaint to be made about it is that, if you were to hazard a guess, you might assume it to be two or three years older than it actually is. Barring the addition of a 360-degree panning system, the interface and presentation of the game aren’t very far removed at all from what we were seeing at the beginning of the point-and-click phase of Legend’s existence in 1993. For example, there’s still no audible narrator guiding the show, just lots and lots of textual descriptions of the things you click on. (The characters you speak to in the game, on the other hand, are fully voice-acted.) Its dated presentation may have represented a marketing problem when Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon made its debut in the spring of 1997, but there’s no reason for it to bother tolerant retro-gamers like us unduly today.

Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon was the last hurrah for Legend’s original adventure engine, which had been steadily improved since their very first game, 1990’s Spellcasting 101.

So much for objectivity. Subjectively, this is my least favorite point-and-click Legend adventure game, with the possible exception only of Companions of Xanth, for which my distaste is driven more by the pedophiliac overtones of the books on which it is based than by anything intrinsic to the game itself. I can’t accuse Spider Robinson of so serious an offense as that, only of a style of humor to which I just don’t respond. Alas for me, Josh Mandel chooses to ape that style of humor slavishly. This game is a hall of mirrors where every pane of glass hides a wretched pun or a groan-inducing dad joke or a pseudo-heart-warming “I feel you, man!” moment. It sets my teeth on edge.

And the thing is, you just can’t get away from it. Josh Mandel has chosen to implement every single thing you see in the scenery as a hot spot. And because this is a traditional adventure game, any one of those hot spots could hide the thing or the clue or the action you need to advance. So, you have to click them all. One by one. And it’s absolutely excruciating. The words just run on and on and on… so many words, vanishingly few of them funny or interesting, a pale imitation of a writer I don’t like very much in the first place. I get tired and fidgety just thinking about it. For me at least, Callahan’s is proof that it’s possible to over-implement an adventure game, with disastrous effects on its pacing — a problem that tended not to come up in the earlier years of the genre, when space constraints served as a natural editor.

But of course, it’s well known that comedy is notoriously subjective. You might respond very differently to this game, especially if Spider Robinson happens to be a writer you enjoy, or perhaps if the humor in Sierra’s comedy adventures is more to your taste than it is to mine. I’d be lying if I said I finished it — dear reader, there came a point when I just couldn’t take it anymore — but what I did see of it gave me no reason to doubt that it’s up to Legend’s usual standards of meticulous, scrupulous fairness.

Sadly for Legend, Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon sold like a Popsicle in the Arctic. And small wonder: whatever its intrinsic merits or demerits, it’s hard to imagine a game more out of touch with the way the industry was trending in 1997. In light of this, that could very well have been that for Legend Entertainment as a maker of adventure games. Instead, the company ponied up for one last adventure while the drawn-out Wheel of Time project was still ongoing. It was permitted only a limited budget, but it seems like a minor miracle for ever having gotten made at all. Best of all, John Saul’s Blackstone Chronicles: An Adventure in Terror is really, really good.

This project was an unusual one for Legend, in that for once the author behind the literary work that was being borrowed from showed an active, ongoing interest in the game. John Saul was riding high at this point in his career, being arguably the most popular American horror writer not named Stephen King. He was also, as he said at the time, “an old computer gamer, going back to the days of Zork when the adventure was all in text.” He first began to speak with Bob Bates about some sort of collaboration as early as 1995. The two initially discussed a book and game that would be released at the same time, to serve as companion pieces to one another. When that became too logistically challenging — a book tends to be a lot faster to create than a game — they decided that the game could come out later, to serve as a sequel to the book. Even so, Bates was already sketching out a design at the same time that Saul was writing his manuscript.

In the midst of all this, the aforementioned Stephen King tried out a unique publication strategy for his story The Green Mile: in an echo of the way the Victorians used to do these things, it appeared as six thin, cheap paperbacks, one per month over the course of half a year. The experiment was a roaring commercial success, convincing John Saul that it would serve his own burgeoning Blackstone Chronicles equally well. Thus the latter too was published in six parts over the first half of 1997 (after which the inevitable omnibus volume which you can still buy today appeared).

The Blackstone Chronicles revolves around an old, now abandoned asylum that looms physically and psychically over the New Hampshire town of Blackstone. In each of the first five installments, a resident of the town receives a mysterious gift of some sort, an object that once belonged to one of the inmates of the asylum. Strange events ensue on each occasion, until it all culminates in a showdown between a dark past and a hopefully brighter future in the sixth installment. The Blackstone Chronicles isn’t revelatory — creepy asylums in bleak New England towns aren’t exactly the height of innovation in horror fiction — but I found it to be a very effective genre piece nonetheless, one that’s wise enough to understand that shadows in the mind are always scarier than blood on the page. It was also a commercial success in its day to rival its inspiration The Green Mile, with each of the installments reportedly selling in the neighborhood of 1 million copies.

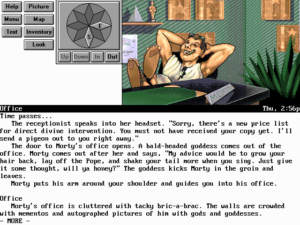

Sales figures like that do much to explain why Legend decided to continue with their game of The Blackstone Chronicles despite the headwinds blowing against the adventure genre. The project marked the first time that Bob Bates had taken on the role of Lead Designer since Eric the Unready back in 1993. Designing games was what he had started Legend in order to do, but navigating the shifting winds of the industry had come to demand all of the time he could give it and then some. Now, though, the situation was a bit more settled, thanks to GT Interactive stepping in with a long-term commitment to The Wheel of Time. Not being an FPS gamer, Bates wasn’t sure how much he could contribute there. Meanwhile his loyal friend and partner Mike Verdu felt strongly that, if Bates wanted to take a modest budget and make an adventure game with John Saul’s help, he had earned that right. The way things were going for Legend and the industry as a whole, it might very well be the last such chance he would ever get.

Bob Bates looks back on the time he spent making this game about madness, sadism, and tragedy as a thoroughly happy period in his own life. The constant stress over how Legend was to make payroll from month to month had, at least for the time being, abated, allowing him to do what he had really wanted to be doing all along: designing an adventure game that he could be proud of. It was gratifying as well to be working with such a literary partner as John Saul, who was, if far from a constant presence around the office, genuinely interested in what he was doing and always available to answer questions or serve as a sounding board. The contrast with most of the authors Legend had worked with in the past was stark.

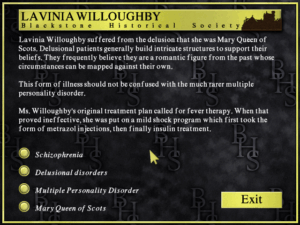

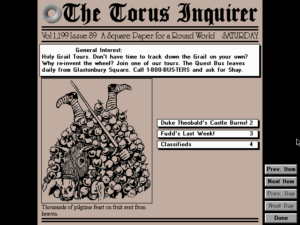

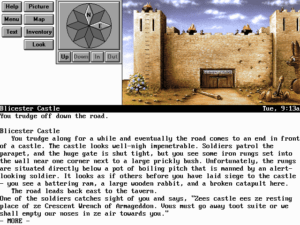

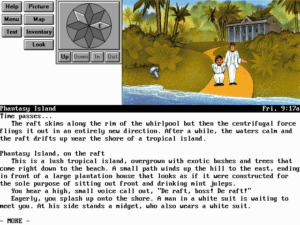

The game takes place several years after the last of John Saul’s novellas, casting you in the role of Oliver Metcalf, the son of Malcolm Metcalf, the Blackstone Asylum’s last and most infamous superintendent. With a plan to demolish the old building and erect a shopping center in its place having backfired in the books, the town council now wants to make a museum of psychiatric history out of it. Before the museum can open, however, Malcolm’s malevolent spirit kidnaps your — Oliver’s, that is to say — flesh-and-blood son and hides him somewhere in the building. You go there to rescue him, which is exactly what your father wants you to do, having hatched a special plan for your soul. It’s a classic haunted-house setup, no more original in the broad strokes than the premise of the books, but executed equally well. The museum conceit is indicative of the design’s subtle cleverness: the exhibits you find in each room fill in the backstory of what you’re seeing, making the game completely accessible and comprehensible whether you’ve read the books or not.

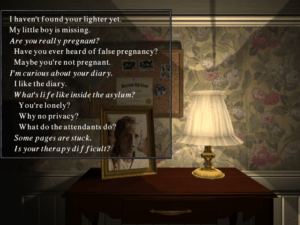

Instead of pulling out Legend’s standard third-person adventure engine for one more go-round, Bob Bates opted for a first-person perspective with node-based movement through a contiguous pre-rendered-3D space — i.e., the sturdy Myst model, which Legend had previously used only for Mission Critical. With most of the small company busy with The Wheel of Time, the majority of the graphics and much of the programming were outsourced to Presto Studios, who were just wrapping up their third and final Journeyman Project game and were all too eager for more projects to take on in these declining times for the adventure genre. The end result betrays that the budget was far from expansive, but the sense of constrained austerity winds up serving the fiction rather than detracting from it.

Indeed, the finished game is something of a masterclass in doing more with less. The digitized photographs that drift across the screen from time to time serve just as well or better than full-fledged expository movies might have. Then, too, The Blackstone Chronicles uses its sound stage as effectively as any adventure game I’ve ever played; when I think back on the experience, I remember what I heard better than what I saw. Artfully placed creaks and groans and grinds and drips keep you from ever feeling too comfortable as you roam, as does the soundtrack, all brooding minor chords that swell up from time to time into startling crescendos.

And then there are the disembodied voices you converse with as you explore the asylum, who are sometimes deeply unsettling, sometimes downright heart-wrenching. In the category of the former is an all-American boy who talks like a cast member of Leave It To Beaver, but who has found his true calling as the operator of the asylum’s basement torture chamber, where iron maidens are only the tip of a sadistic iceberg. (“When I was a teenager, I killed a few animals and skinned them. People got upset. They said something was wrong with me. I guess what tipped the balance was when I cut up my best friend and put him in my closet…”) In the category of the latter is a little boy who prefers to wear dresses. Following the theories of the real psychiatrist Henry Cotton that such “disorders” of the mind reside in an organ of the body, Malcolm Metcalf proceeded to dismantle the boy piece by piece, beginning by pulling out his teeth and proceeding on to liver, spleen, kidneys, eyes, ears, and finally limbs. Standing there in a bare little room, surrounded by the remnants of the boy in Mason jars, listening to him tell his story… well, I found it fairly shattering. I’m not scared of werewolves or vampires, but I can be scared by monsters who appear in the guise of ordinary humans.

The fact is that many of the horrors The Blackstone Chronicles unveils really did happen inside mental institutions, and not all that long ago. During Medieval and Renaissance times, convents were the places one used to hide away embarrassing or inconvenient family members — usually women. (When Hamlet tells Ophelia to “get thee to a nunnery,” it isn’t meant as a tribute to her religious devotion.) So-called “lunatic” asylums took over this role during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. When in The Blackstone Chronicles you meet the spirit of an unmarried young woman who tells you she is pregnant, you don’t know whether to believe her own words or to believe her official admission record, which says that she is suffering from an “hysterical pregnancy.” You just know that your heart goes out to her.

The puzzles you encounter as you explore the asylum and engage with its inmates and their persecutors aren’t exceptionally memorable in and of themselves, but they do their job of guiding your progress through the drama; in an echo of the books, they’re mostly object-oriented affairs, with most of the objects being intimately connected to the people who once lived here. Every once in a while, Oliver gets tossed into a situation that led to the death of an inmate: he might get locked inside the “heat chamber,” get hooked up to an ECT (“electroconvulsive therapy”) machine, or find himself strapped down underneath a swinging pendulum straight out of Edgar Allan Poe. If you don’t escape in time, you die — but never fear, the game gives you a chance to try again, as many times as you need. These sequences are as minimalist as the rest of the game, doing much with a few still frames and the usual brilliant sound design. And once again, the end result is more unnerving than a hundred blood-drenched videogame zombies.

The Blackstone Chronicles definitely isn’t for everyone; some might find it traumatizing, while others might simply prefer to play something that’s a little bit more cheerful, and that’s perfectly okay. But if it does strike a chord with you, you’ll never forget it. It’s one of only a few games I’ve played in my life that I’m prepared to call haunting — not haunting in a jump-scare sort of way, but in the way that can keep you up at night, wondering what on earth is wrong with us that we can do the things we do to one another.

If anyone had thought that being tied to such a successful series of books would make the game of The Blackstone Chronicles a hit in its own right, they were destined to be disappointed. GT Interactive saw so little commercial potential in Legend’s side project that they didn’t even want to distribute the game. Released in November of 1998 under the auspices of Red Orb Entertainment, a division of Mindscape, it performed only slightly better than Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, offering up no justification whatsoever for Legend to continue to make adventure games even as a sideline to their new direction. The future of the studio founded as the heir to Infocom lay with first-person shooters.

What was there to be said about that? Only that it had been one hell of a transformative decade for Bob and Mike’s most-excellent adventure-game company, as it had been for gaming in general.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Masters of DOOM: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture by David Kushner, Madhouse: A Tragic Tale of Megalomania and Modern Medicine by Andrew Scull, Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon by Spider Robinson, and The Blackstone Chronicles by John Saul. Computer Gaming World of August 1996, December 1996, February 1997, September 1997, January 1999, and February 1999; Retro Gamer 180; PC Gamer of December 1995. and May 1996

Online sources include GameSpot’s vintage review of Star Control 3 and an old GA Source interview with Michel Kripalani of Presto Studios.

I also made extensive use of the materials held in the Legend archive at the Strong Museum of Play.

In addition to the above, much of this article is based on a series of conversations I’ve had with Bob Bates and Mike Verdu over the last ten years or so. My thanks go to both gentlemen for taking the time out of their still busy careers to talk to me.

Where to Get Them: Star Control 3 is available for digital purchase at GOG.com. Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon and The Blackstone Chronicles can be downloaded as ready-to-run packages from The Collection Chamber; doing so is not, strictly speaking, legal, but needs must.