In his expatriate memoir Notes from a Small Island, Bill Bryson describes what a false picture of the world’s geography you would end up with if you were to try to surmise it from British mass media. Britain, you would probably assume from the crazy amount of attention the United States gets in that country’s press, must lie somewhere just off the coast of North America, perhaps about where Cuba lies in reality. It would be the rest of Europe that is separated from Britain by a wide, daunting ocean.

The retro-gaming scene of today can give a similarly false picture of the geography of gaming’s past — one that is not so trivial to correct. Take the case of the fondly remembered studio Dynamix, a major name in gaming from 1984 until 2001. Do you know what Dynamix’s most profitable game of all was? It was not any of the ones that are still discussed today: not Arcticfox or Rise of the Dragon, not The Red Baron, not The Incredible Machine, not Betrayal at Krondor, definitely not Rama. No, it was a little something called Trophy Bass, which sold many more copies from the outdoor sections of Middle American Wal-Mart superstores than it did from computer and gaming stores. As of this writing, Trophy Bass has precisely zero reviews on the central fandom database MobyGames. And yet it was absolutely huge in its day — eclipsed, in fact, only by the unrivaled king of Wal-Mart software: Deer Hunter, the butt of a million hardcore-gamer jokes, whose publisher laughed all the way to the bank.

Indeed, Deer Hunter must be solidly in the running for the title of most profitable single computer game of the twentieth century, easily outdoing such hardcore contemporaries of the late 1990s as Quake, Diablo, and Starcraft in terms of the amount of money it cost to create versus the amount of money it brought in. Its only real challenger by this metric may be the unstoppable juggernaut that was Myst, another game that was made on a shoestring and then proceeded to sell and sell and sell some more, despite being widely scorned by the hardcore crowd. Then again, there is Barbie Fashion Designer to consider as well. Guess how many MobyGames reviews it has… Suffice to say that targeting the people who self-identify as “gamers” has seldom if ever been the best way to make a lot of money in games.

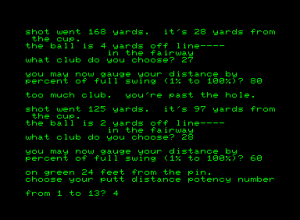

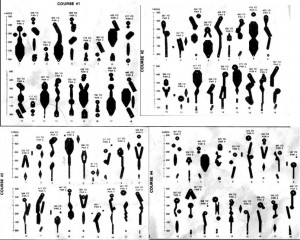

With that in mind, let me spin you a yarn about Access Software, which existed in or close to Salt Lake City, Utah, from 1983 until 1999, at which point it was acquired by that biggest whale of all in the software scene, Microsoft itself. Today, Access is remembered by retro-gamers mostly as the home of Tex Murphy, a trenchcoat-and-sneaker-clad detective of a noirish future who was played onscreen by Access’s chief financial officer Chris Jones in five installments spanning from 1989 to 1998. Yet it wasn’t Tex, whose commercial profile never exceeded the fair-to-middling range during his heyday, who convinced Microsoft that Access was an investment worth its time. That service was performed by Links, a long-running series of golf simulations that got slightly more attractive and sophisticated every year throughout the 1990s, and was rewarded by becoming a staple of another demographic that stayed far away from most computer games: the middle-aged corporate-executive set, the same people who could be seen out on the world’s real golf courses.

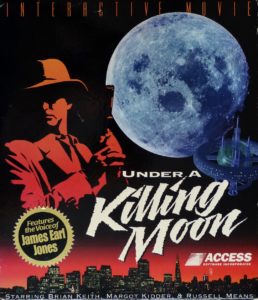

From first to last, Tex Murphy was an indulgence which Bruce Carver, the founder of Access, permitted to Chris Jones, his longest tenured and most valued employee, who had been with the company from its earliest days as a maker of Commodore 64 action games. This is not to say that Tex didn’t assemble a fan base of his own, most of them people who would never have touched a golf simulation. He really hit his stride with the third game of the series, 1994’s Under a Killing Moon, which earned its label of “interactive movie” by using live-action video clips of real actors rather than crudely digitized still photographs to carry its narrative water. This was also the point where a fellow named Aaron Conners came aboard as scriptwriter and Jones’s design partner, engendering a quantum leap forward on those fronts as well. Technologically innovative and yet thoroughly lovable in an enthusiastic community-theater sort of way, Under a Killing Moon became the most commercially successful Tex Murphy game ever, selling almost 500,000 copies. Such numbers may have paled beside those put up by Links, but they were sufficient to permit the series to continue to exist as a sideline to Access’s mainline in simulated golf.

Unfortunately, that equation got upended by 1996’s The Pandora Directive. The fourth Tex Murphy game and second full-fledged interactive movie pushed harder and farther along all the trails blazed by its immediate predecessor: its play time was longer, its plot more convoluted, and its formal storytelling ambitions more pronounced, with a welter of different endings on offer depending on how you chose to play the dubiously great detective. All that notwithstanding, once cast adrift in a changing marketplace where interactive movies were now a dime a dozen and already encountering the first worrying signs of a gamer backlash, it sold only about a third as many copies as Under a Killing Moon, not even enough to pay for its own production cost.

By all rights, that should have been that for Tex Murphy. Bruce Carver may have been an indulgent man, but he would have had to be a terrible businessman indeed to let his CFO’s passion project go on actively losing his company money. As it happened, though, Tex got thrown a lifeline from a most unexpected source. To understand the circumstances that led to his rescue, we need to take a quick look back at the history of, of all things, the storage media that were used to deliver software to consumers during the first quarter-century of the personal-computer era.

By the mid-1990s, the computer industry had already passed through two fairly earthshaking transitions in storage media: the linear medium of cassette tapes had been replaced by random-access floppy disks, which had in turn been largely superseded by CD-ROMs that could hold over 400 times as much information as what had come before. It’s interesting to note that the first and third links in this chain first came to prominence not in association with computers but as music-delivery technologies. While the application of cassette tapes to the very first personal computers of the late 1970s was a happy accident, the inventors of the CD took to heart from the start a brilliant insight of the early computing researcher and theorist Claude Shannon: that all data is ultimately just data; the difference exists only in the way you interpret it. Thus when the CD made its debut in 1983, Philips and Sony, the Dutch and Japanese electronics giants behind the new format, envisioned music delivery as only the first of a whole range of applications. For, being a digital storage medium, all a CD contained at bottom was a string of ones and zeroes, which could presumably be applied to whatever purpose you liked: computer code and data, video, you name it.

In the end, though, the proud parents’ hopes and schemes for the format were realized only partially. After an agonizingly long gestation period, CD-ROM drives for computers finally broke through to become a ubiquitous reality circa 1993. Yet the territory of home video remained resolutely unconquered by the little silver discs. In 1993, people were still buying and renting movies on VHS videotapes (and, in much smaller numbers, on laser discs, an almost equally aged storage medium despite its futuristic appearance). The principal problem holding the CD back was that of capacity. The 650 MB or so that could be stuffed onto a CD were enough to provide 75 to 80 minutes of high-fidelity music, more than enough for a symphony or even most double record albums. When it came to video, however, the numbers didn’t look so good. It just wasn’t possible to put enough decent-quality video onto a CD to compete with VHS. Not that people didn’t try: a number of initiatives sought to make up the difference through hyper-aggressive compression algorithms, but none of them were very satisfying and none of them went much of anywhere in the developed West.[1]Despite the many compromises inherent to the concept, video CDs did become quite popular in the still-developing regions of Asia and Africa, where they often took the form of bootleg discs sold at street markets and the like. On computers as well, video-centric games like Under a Killing Moon and The Pandora Directive were soon bumping into the limits of the CD; the latter shipped on no fewer than six discs, and yet the quality of its video snippets was far below what you would expect from an ordinary television broadcast.

It didn’t take a genius to see what was needed: a new optical storage medium much like the CD in form and spirit, but much more cavernous. It was so obvious, in fact, that by the end of 1994 two separate successor standards were in development, one from the old CD consortium of Philips and Sony, the other from Toshiba, each with more than half a dozen other major names in home electronics signed on as supporters. The stage seemed to be set for a repeat of the VHS-versus-Betamax format war of the early years of videotape. VHS had finally won that conflict to become the universal standard, but it hadn’t been quick, easy, or cheap. As with most wars, everyone involved would probably have been better off if it could have been avoided.

No one was more worried about the prospect of a Second Video Format War than the big players of the computer industry. They assumed that, just as they had adopted CD technology to their own use-case scenarios, they would do the same with this successor technology. Two dueling formats, however, would be a nightmare for them. They wanted — no, needed — a single standard; the alternative was too chaotic to contemplate. Apple, Compaq, Fujitsu, Hewlett Packard, IBM, Microsoft, and Sun therefore came together in April of 1995 to create a working group whose marching orders were to put pressure on the feuding parties in the adjacent home-electronics industry to join forces and come up with a single standard.

In a telling testament to the computer industry’s growing clout in this burgeoning new Internet Age, the pressure campaign was successful in relatively short order. On December 12, 1995, the basic specifications of the DVD were formally agreed upon by everyone concerned. The format inherited parts of both research projects to wind up with an optical disc capable of holding more than 8.5 GB of data, which could constitute up to four hours of crisp video and audio, compressed using the nearly lossless MPEG-2 standard — or, alternatively, the data on the disc could be used for whatever other purpose you had in mind, just as with a CD. The DVD would be slightly thicker than a CD, but would otherwise have the same form factor, such that it would even be possible to read CDs in DVD drives. Like the technology itself, the acronym was a classic product of corporate compromise. It wasn’t really an acronym at all: the parties couldn’t agree whether “DVD” stood for “Digital Video Disc” or “Digital Versatile Disc,” so they decided that a DVD would just be a DVD, full stop.

The standard’s progress from prototypes to products was almost derailed by the Hollywood film studios, who wanted a delivery medium that was, unlike VHS, secure against piracy. A variety of copy-protection mechanisms had to be implemented to placate the studios, including a system of regional locks whereby DVDs could only be played in that part of the world where they had been purchased. At last, on November 1, 1996, the very first DVD players from Matsushita and Toshiba, the honor guard for the hundreds of millions that would follow, went on sale in Tokyo’s legendary Akihabara electronics district. Americans had to wait until the following February for the first units from Panasonic and Pioneer to arrive. Within four months, 30,000 of them had been sold. From there, the numbers swelled exponentially. By the end of 1997, 340,000 standalone DVD players had already been sold in the United States alone, along with a million or more movies on disc to watch with them. It was just the beginning of what would soon be credibly labeled “the most successful consumer-electronics entertainment product of all time.”

On computers, however, the DVD’s forward march was more halting. Singapore’s Creative Labs, which had made its name and its fortune fueling the multimedia-computing revolution with sound cards and CD-ROM drives, introduced its first DVD-ROM upgrade kit in April of 1997, but it was rendered nearly unusable by a lack of driver support in Microsoft Windows. Oddly, considering how hard it had worked to ensure that the DVD standard was a standard, the computer industry seemed caught flat-footed by the actual presence of the technology it had shepherded out in the wild. It seemed not to have adequately considered the complications involved in combining DVDs with personal computers — especially when it came to using DVDs for their most obvious purpose of all, as repositories for high-quality video.

The embarrassing fact was that even most of the high-end microprocessors of the day didn’t have enough horsepower to be able to decompress the MPEG-2 video fast enough as it streamed off the disc. The only viable solution to this problem was the one used by standalone DVD players: another layer of hardware in addition to the interface between the computer and the DVD drive itself, a set of specialized circuits that could decompress the data coming off the DVD fast enough to get it to the screen in real time.

Enter Intel, the maker of most of those CPUs that weren’t quite up to the job of handling DVD video on their own. Although it hadn’t been part of the computer industry’s initial push to force a DVD standard, Intel had grown very bullish indeed on the format since then. During his keynote address at the January 1997 edition of Comdex, the industry’s biggest annual trade show, Intel’s CEO Andy Grove played snippets of Space Jam from a DVD drive connected to a computer. He and his associates envisioned a DVD player as the key component of a multimedia set-top box for the living room, sort of like a games console but also something more — an idea which never seemed to die, despite the failures of many previous entrants into this space, from Commodore to 3DO. As a first step toward this fondly imagined future, Intel set out to make a new line of upgrade kits for existing computers, to consist of a DVD drive and a new video card containing the hardware needed to get MPEG-2 video efficiently to the screen.

Strange though it may sound, these initiatives became Tex Murphy’s momentary savior.

It is a longstanding truism in computing that hardware is useless without software. Translated into the language of consumer electronics, this means that, if you want people to buy your shiny new gadget, you need to make sure they can also acquire compelling things to do with it. This was the reason that it was so important to win Hollywood’s acceptance of the DVD standard — important enough to delay the first DVD players’ release and to redesign the whole specification, just to ensure that exciting, sought-after movies arrived on store shelves alongside those first DVD players. Intel found itself in a similar bind when it considered its foray into interactive DVDs: there was currently no software out there to make use of them. What, any potential customer would ask very reasonably, am I supposed to actually do with this thing?

This was anything but a new problem for the computing and gaming industries. Luckily, it wasn’t an insoluble one either, as long as you had sufficient foresight and money. Two decades previously, Atari had solved it by having its own people make a range of fun games for the Atari VCS console before the latter ever went to market; then, when it did, Atari packed one of the best of those games — the soon-to-be-iconic Combat — right into the box with the console. A decade and a half later, third-party “pack-in” games became standard in the multimedia upgrade kits of companies like Creative, for the same reason Combat had shipped with the Atari VCS: to give people something to do with their new toy right away. When accelerator cards for 3D graphics became available a few years later, the purveyors of same paid game publishers a lot of money to make special versions of hit titles that were optimized for their particular cards. Activision, for example, programmed at least half a dozen separate versions of MechWarrior 2 for the different would-be graphics-accelerator “standards” that were floating around at the time. Such pack-ins could be of enormous importance to everyone concerned: the profits that Activision raked in from MechWarrior 2 helped to set one of gaming’s most venerable brand names back on the road to ubiquity after an ugly bankruptcy at the beginning of the decade.

Now, Intel wanted to prime the pump of interactive DVD with a showcase pack-in title that would demonstrate to everybody what the technology was capable of, and that would give customers something to do while everyone waited for a real software ecosystem to develop around the product. Somebody inside the mega-corporation was evidently a fan of Tex Murphy, thought that Chris Jones and Aaron Conners and their colleagues at Access Software were the perfect people to put interactive DVD through its paces. By no means was it an untenable deduction; no more credible stabs at interactive movies on CD existed than Under a Killing Moon and The Pandora Directive. What might Access be able to do with DVD-quality video?

Thus one day a lifeline for Tex Murphy fell out of the clear blue sky, when Intel came to Access with an offer that would have been difficult for anyone to refuse. Intel would pay all of the production costs of a third Tex Murphy interactive movie. The only requirements were that the finished game had to run from DVD and had to be given to Intel to include as a pack-in with any and all of its interactive-DVD products. Access, for its part, would be allowed to sell the game on its own in a conventional retail box, keeping whatever revenues it generated thereby; if it chose, it could also make a version that ran from CD and sell that as well. Intel wasn’t even all that worried one way or the other about how much the game would cost to make, given that, whatever the final budget wound up being, it was guaranteed to be chump change for the biggest maker of computer chips on the planet. There was just one sticking point: Intel needed the game within one year. Time, in other words, was more important than money.

Being in no position to look a gift horse like this one in the mouth, Jones and Conners accepted all these terms without a second thought. Only after they had signed the contract did they sit down to consider just what it was they had agreed to. The last two Tex Murphy games had each taken twice as long to make as the amount of time Intel was giving them to make this one. They had sketched out only a rough outline of a plot for a possible next game in the series. Their chances of turning this into a finished script and then turning that script into a finished game they could be proud of within a single year seemed nonexistent.

At this point, Chris Jones came with a suggestion. Why not remake Mean Streets, the very first game in the series from 1989? They could dust off the old design document, flesh it out here and there, and present it as the origin story of the current incarnation of Tex Murphy, Private Investigator. Aaron Conners, who had never even played Mean Streets, said it sounded fine to him.

He was less sanguine when he did try the game, an awkward melange of flight simulator and point-and-click adventure which made it abundantly clear why Jones had felt the need to find a proper writer to join him for Under a Killing Moon. The first no-brainer decision was to throw the flight simulator right out. And then, says Conners:

I went to [Chris] and I said, “We can’t redo this game. This is terrible. You’ve got more jokes from third grade in here than I’ve ever seen in a game.”

I took the basic thread of the story and rewrote everything around that. I rewrote the script from top to bottom. And so, when people say Tex Murphy: Overseer was just a redo of Mean Streets, I want to throttle them, because I worked harder on that than I did on Pandora.

Adrian Carr, who had directed the live-action video in The Pandora Directive, returned to do the same for Tex Murphy: Overseer. (The new name reflected Access’s belated realization that borrowing the title of one of Martin Scorsese’s most beloved films was a recipe for consumer confusion if not legal peril…) The casts of both of the previous games had been a blend of Salt Lake City locals with a handful of moderately recognizable film actors — people like Margot Kidder, Barry Corbin, Kevin McCarthy, Tanya Roberts; even James Earl Jones, the voice of Darth Vader, had agreed to join Under a Killing Moon as the narrator. Overseer continued this tradition, leaning perhaps a little harder than before on the Hollywood crowd at the expense of the locals. (It was, after all, being made on Intel’s dime.) The big coup this time was the highly respected veteran of stage and screen Michael York, who even as the game was in production was making a splash with a whole new generation of moviegoers thanks to his role in the hit James Bond spoof Austin Powers. Here he played the villain, albeit an unusually complex and tortured one, whose final monologue might just be the best thing Aaron Conners ever wrote.

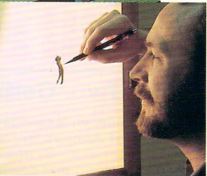

Everyone involved with Overseer speaks of it as a more regimented project than the ones before, a case of making a plan and sticking to it. With so little time to work with, there was hardly any other way to approach it. The filming in particular took on the rhythm of a conventional Hollywood shoot, with the actors cycling through like clockwork to do their scenes one after another over the course of about a month. (The only actor present throughout the shoot was the star of the production, the unlikely amateur Chris Jones.) In all facets of the project, the Access folks kept the faith and worked like dogs. And they got it done, delivering Tex Murphy: Overseer right on schedule in the first weeks of 1998.

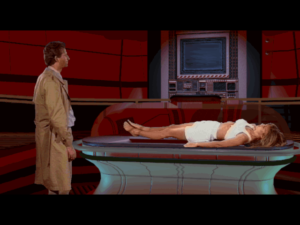

The game’s fiction stays on familiar territory. The setup is pure film noir: Tex is visited in his office by a femme fatale named Sylvia Linsky, who will, as those of us who played the other games know, eventually become his wife and then his ex-wife. Right now, though, she explains that she is suspicious about her father’s recent untimely death; he is supposed to have thrown himself off the Golden Gate Bridge in a fit of despair, despite having never displayed any signs of depression or suicidal tendencies before. Tex’s investigation leads him down the standard rabbit hole of a world-spanning and potentially world-ending conspiracy, involving secret brain implants that can be used to control the minds of millions of people. All of this may be par for the course for a Tex Murphy game, but this is by no means a bad execution of the standard formula. As usual, comedy and drama sit side by side in a way that would be awkward in most storytelling situations, but something in the Tex Murphy special sauce allows it to work far better here than it has any right to. And then, as I already mentioned, there’s some real pathos and gravitas to the villain’s arc, qualities which are elevated that much further by the performance of Michael York, one of those Shakespearean-trained British actors who would sound pretty great reading the phone book aloud.

It is true that Overseer lacks the divergent paths and multiple endings of The Pandora Directive. That said, I must also say that I’m a bit of a curmudgeon about such formal experiments in otherwise traditional adventure games anyway, rarely finding them worth the additional disc space and development time they entail. I’m perfectly happy with one satisfying story line, which is plenty hard enough to offer up. Overseer manages that feat, and that’s good enough for me.

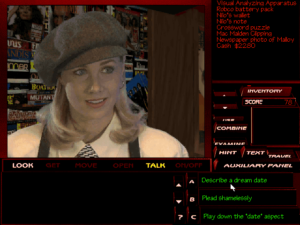

In lieu of a branching plot, there is one really interesting wrinkle in the game’s approach to its narrative. It’s explicitly framed as a story which the present-day Tex, a more jaded figure than his earlier incarnation, is telling to his current love interest Chelsee over the course of an evening out. If you screw up or get Tex killed — which are usually one and the same, come to think of it — you see a little clip of his present-day self telling Chelsee, “No, that’s not really how it happened!” In his review for Computer Gaming World magazine, Charles Ardai took exception to the approach, complaining that the existence of Tex in this later time means that “the outcome is not in doubt. Tex must prevail, or he wouldn’t be sitting here talking to Chelsee.” That’s true as far as it goes, but I must say that it doesn’t go all that far with me. Has anybody ever played any Tex Murphy game under the misapprehension that the hero might not win out in the end? Not since Infocom’s Infidel created a backlash in 1983 had anyone dared to make an adventure game with a non-telegraphed tragic ending. Personally, far from being dissatisfied with it, I only wish that Overseer leaned into its storytelling conceit a little more. It could, for example, automatically send you back to the juncture in the story where you messed up after you reach one of the bad endings, rather than dumping you back to the menu to manually load the saved state you hopefully remembered to create. This game is ultimately all about its story, so why not make it as effortless as possible for us to play with the stuff of the story?

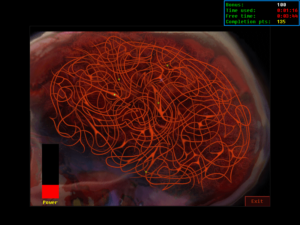

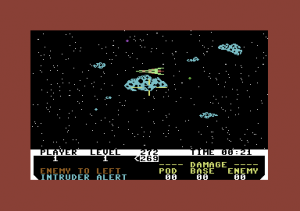

The gameplay itself is tried and true for this series. Once again, you spend most of your time either interrogating suspects via a menu of conversation topics or exploring locations and solving puzzles from a free-roaming first-person perspective — no Myst-style fixed movement nodes here! Whether you’re alternately crouching and standing on tiptoes in order to search every hidden corner of a room for clues or dodging hit men or killer robots in a surprisingly dynamic possibility space, the stuff you do when you aren’t watching canned video clips is what elevates the Tex Murphy series above almost all of its interactive-movie peers. For these are interactive movies that truly work as games — as rich, generous adventure games, with challenging but meticulously fair puzzles and even a modicum of emergent qualities when the action starts to heat up.

Although Overseer doesn’t reinvent any of its predecessors’ wheels, the evolution of computer technology has made the presentation everywhere that much sharper and crisper in comparison to what came before, especially in the video snippets — only appropriately, given that they were the whole point of the endeavor from Intel’s point of view. Indeed, I find I want to say that Overseer is actually better than its rather middling reputation within modern Tex Murphy fandom. It’s a little shorter than Under a Killing Moon or especially The Pandora Directive, but it’s not all that short in the abstract; there are still a good five to eight hours of fun to be had here.

The worst thing I can say about Overseer is that it’s just a little bit less Tex Murphy than its predecessors in senses other than length. The more conventionally professional performances and even presentation can be a double-edged sword, detracting just slightly from that giddy community-theater quality that made the earlier games so ridiculously charming. There aren’t many games or game series about which I would make such a statement — camp is most emphatically not my thing in general — but Tex Murphy has always been special in that regard, simply because there’s so darn much amateurish “we’re making an (interactive) movie!” joy to be found there, because the whole thing is so darn open-hearted and guileless. With Overseer, though, there is just a hint of ennui threatening somewhere out there on the horizon.

Still, and for all that this isn’t the place I’d recommend that anyone start with Tex Murphy — you should definitely play the classic 1990s trilogy in release order, beginning with Under a Killing Moon — Overseer remains from first to last an entertaining, well-crafted, and thoroughly enjoyable adventure game, just like its companion pieces. I’m happy to give it a place alongside them in my personal Hall of Fame. If more 1990s interactive movies had been like these ones, the world may or may not have been a better place, but adventure-game fans would for sure have had a lot more fun in it.

Michael York plays the tortured, tragic villain, the wheelchair-bound billionaire J. Saint Gideon. Aaron Conner counts York saying to him out of the blue one day that the role of Gideon was a little bit “Shakespearean” as one of the great thrills of his life.

The journeyman Australian stuntman and martial artist Richard Norton played Big Jim Slade, a more hands-on sort of heavy than Gideon. Norton was a great find, portraying Slade with a humorous panache that Conner hadn’t really written into his script. Many of his best lines were ad-libbed on the spot.

The name of Delores Lightbody, the former fiancée of Sylvia Linsky’s deceased father, is a piece of third-grade humor from Mean Streets that somehow survived into Overseer. The tired fat-shaming tropes on display here are among the few aspects of the Tex Murphy series that have aged decidedly poorly. Ah, well… to her credit, actress Micaela Nelligan attacks the role with relish. “Incredible!” said Rick Barba, who wrote the strategy guide for the game. “I found myself attracted to this big woman!” (I’m sure you’re a downright Adonis yourself, right, Rick?)

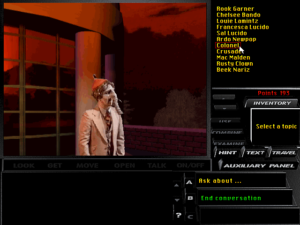

Out and about in the world. The interface is notably less clunky than in the previous two games. Now you can access your inventory on the fly just by moving the cursor to the side of the screen, instead of having to freeze the view in place and enter a separate object-manipulation mode.

In marked contrast to his hard-boiled detective heroes, Tex never fails to look painfully awkward whenever the possibility of a seduction arises. Far from being a weakness, this is a big source of the series’s goofy Mormon lovability.

When the folks from Access delivered Tex Murphy: Overseer, a game of which they felt justifiably proud, they were brought up short by an ironic turn of events that would have amused Tex himself at his most cynical. To put it bluntly, Intel didn’t want the game anymore. While Access had been beavering away at it, Intel had belatedly begun to ask itself some hard questions about where — or rather whether — its vision for interactive DVD actually fit. In reality, standard DVD was already far more interactive than the linear medium of VHS. A new era of movie watching was dawning, in which viewers could jump to favorite scenes instantaneously, could listen to directors’ commentaries and alternative soundtracks while they watched, could enjoy additional interviews and “making of” featurettes included on the same disc as the movie, could switch up languages and subtitles on the fly. Some companies were even experimenting with making the direction of the movie itself interactive, the cinematic equivalent of those old Choose Your Own Adventure books. All of this was possible using the standard DVD specification running on any everyday DVD player. Did people want to pay for additional hardware in order to run a full-fledged video-based adventure game like Overseer? Intel had a dawning suspicion that they did not. Certainly there could be no denying now that CD-based games of this style were in marked commercial decline, having been trampled by the latest crazes for 3D action and real-time strategy, not to mention the Deer Hunters and Trophy Basses of the world.

And then, for the final irony, Intel’s custom DVD technology was fast becoming irrelevant even for the purpose of watching ordinary movies on your computer. It was a case of the corporation’s right hand not being fully aware of what its left was up to: Intel’s latest Pentium II CPUs had sufficient grunt to be able to handle MPEG decoding unaided, without requiring any other specialized circuitry in an add-on video card or a set-top multimedia box.

So, Intel decided to drop its most ambitious plans for DVD and focus on the chips that had gotten it this far. With the facility that is the luxury of a giant corporation, it wrote off its multi-million-dollar investment in Tex Murphy: Overseer as just another idea that had seemed good at the time but hadn’t panned out. Access, Intel said, could do whatever it liked with the game.

At first blush, this might have sounded like unbelievably good news to Chris Jones and Aaron Conners. Thanks to Intel, they had a new Tex Murphy game which had literally cost their own company nothing to make, which they could now go out and sell without sharing any of the revenue with anyone else. When you thought about it a little harder, though, the waters were quickly muddied. Access, a company more interested in golf simulations than adventure games for the very understandable reason that the former made it lots and lots of money while the latter did not, must now try to sell Overseer all by itself in a marketplace that was growing ever more prejudiced against this kind of game. There was ample cause to wonder whether the company’s marketers would really give it their all.

Alas, such concerns were amply justified when Access shipped Tex Murphy: Overseer in March of 1998, with both the DVD version and a version on five CDs filled with grainier video in the same box. Overseer was, as far as I’ve been able to determine, the first ever computer game to be made available from its day of release on DVD. (A number of older games of the multiple-CD stripe had been or soon would be repackaged for DVD, including Wing Commander IV, Riven, and Zork: Grand Inquisitor.) But that claim to fame wasn’t enough to overcome desultory promotion and, most of all, the overwhelming sense in gaming culture that games like this one had become painfully passé. Overseer sold considerably worse than The Pandora Directive. Although the money it did bring in was almost pure profit thanks to the largess of Intel, that happy accident did nothing to undermine the business case against making another game of this type, at least in the absence of another patsy to pay for it.

In a fit of optimism, when their heads were dancing with images of Tex Murphy reaching a whole new audience on Intel’s hardware and with Intel’s marketing machine behind him, Jones and Conners had decided to end Overseer on a cliffhanger. Having just finished telling the story of his first case to Chelsee, Tex flies away into the neon night in the back of an air taxi with her at his side — and then the driver turns and appears to shoot both of them at point-blank range. Needless to say, Jones and Conners would not have ended the game that way had they known that they weren’t going to be able to return to Tex Murphy for a long, long time — not until something called Kickstarter came along to offer an alternative way of funding games.

For the time being, the last nail seemed to have been hammered into Tex Murphy’s coffin in April of 1999, when Microsoft acquired Access in a deal whose details have remained secret. This latest mega-corp to come around flashing its money was, admits Aaron Conners, “oblivious to Tex Murphy. They bought us for Links.” Chris Jones was told by his new masters every time he broached the possibility of a revival that there was no place anymore for Tex: “It’s not really an Xbox product, and it’s way too big for casual gaming. Adventure games have died off. We don’t see where you fit.” And that was that.

But while Tex Murphy shambled off into an unwanted early retirement — or perhaps a worse fate, given the ending to Overseer — the new technology to which he owed his final star turn was going from strength to strength. By the end of 1998, there were 1 million DVD players in American homes, and the format was beginning to make inroads in Europe as well. The American DVD market alone would be worth $4 billion in 2000, $8 billion in 2002, $12 billion in 2004, $16 billion in 2007. VHS would follow the opposite trajectory; the very last Hollywood film to be released on videotape was David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence in 2006.

Gaming platforms lagged behind, but not by that much. The latest generation of games, which tended to rely on 3D graphics that were rendered on the fly rather than lots of pre-rendered video, were ironically less demanding of storage space than those that had come before, making the need for an alternative to the CD seem somewhat less urgent for a while. Still, this “while” was fairly brief-lived; as 3D graphics grew in resolution and polygon count, and were supplemented by more and more ambitious soundscapes, the size of games in terms of raw data soon began to increase once again. In 2000, Sony’s decision to use a DVD instead of a CD drive in the PlayStation 2, the successor model to the most popular games console in the history of the world to that point, marked a watershed for games on DVD. Within a couple of years, the format ruled the games roost too.

The impact the shift from CD to DVD had on the nature of games was more subtle than that of the shift from floppy disk to CD; there was a difference of kind about going from 1.5 MB to 650 MB of storage space that was not present to the same degree when going from 650 MB to 8.5 GB. DVDs just helped games to become a little bit more: more aesthetically pleasing, more complex, more approachable. (No, these last two qualities are not in conflict with one another; in many cases, they go hand in hand.) It was, we might say as we strain nobly to bring this back around to Tex Murphy, the difference between Mean Streets and Under a Killing Moon versus the difference between The Pandora Directive and Tex Murphy: Overseer. The difference, that is to say, between a revolution and an evolution. Yet revolutions are often overrated, what with all the chaos and consternation they cause. Evolution can be just fine if it keeps us moving forward. And this the DVD most certainly did for gaming in general, if not for poor old Tex.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Tex Murphy: Overseer: The Official Strategy Guide by Rick Barba, DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text by Mark Parker and Deborah Parker, and DVD Demystified (second edition) by Jim Taylor. Computer Gaming World of November 1995, August 1996, January 1997, February 1997, June 1997, October 1997, and January 1998; Retro Gamer 160.

Online sources include the archive of interviews at the old Unofficial Tex Murphy Web Site and a documentary film on the Tex Murphy series that was put together as part of the Kickstarter campaign for 2014’s Tesla Effect: A Tex Murphy Adventure.

Tex Murphy: Overseer is available for digital purchase on GOG.com. Fortunately, this is the DVD version. Unfortunately, it’s temperamental on modern versions of Windows. PC Gaming Wiki offers some solutions and workarounds for common problems.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Despite the many compromises inherent to the concept, video CDs did become quite popular in the still-developing regions of Asia and Africa, where they often took the form of bootleg discs sold at street markets and the like. |

|---|