It’s widely known by those who are interested in the history of gaming that the videogame industry was hauled into a United States Senate hearing on December 9, 1993, to address concerns about the violence and sex to be found in its products. Yet the specifics of what was said on that occasion have been less widely disseminated. This, then, is my attempt to remedy that lack. What follows is a transcript of the hearing in question. It’s been rather heavily edited by me with an eye toward grammar, clarity, and concision, but always in good faith, making every effort to preserve the meaning behind the mangled dictions and pregnant pauses that are such an inevitable part of extemporaneous speech.

Being a snapshot of a very particular moment in time, the transcript below needs to be understood in the context of that time. I hope that my previous article has provided much of that context, and that the links, footnotes, and occasional in-line comments in the transcript itself will provide the rest. I cannot emphasize enough, however, the importance of the fact that the hearing took place during a major spate of violent crime. Many of the other “murder panics” of American history had little relationship to the true statistical levels of violent crime, having been drummed up by disingenuous leaders and accepted by their credulous followers for reasons of emotion and prejudice. But there was some justification for this one: 1993 was marked by just a shade under one murder or non-negligent manslaughter for every 10,000 American citizens, the culmination of more than a decade of steadily increasing violence. No one assembled at the hearing could know that violent crime would begin a precipitous plunge the following year, the start of a decline that has lasted almost all the way through to our present year of 2021.

For all that the hearing is of its time in this and countless other respects, there’s also a disappointing timelessness about the affair. Many of the arguments deployed for and against the idea of hyper-violent videogames as a negative social force are little changed from the ones we hear today. Even more dismayingly, the psychological research into the matter is hardly more clear-cut today than it was in 1993, being shot through with the same researcher biases and methodological weaknesses. Much has changed over the past-quarter century, but it seems we’ve made very little progress at all in our understanding of this issue.

But enough of my editorializing. Here’s the transcript so that you can decide for yourself.

As one of the two instigators of the proceedings, Senator Herbert Kohl delivered the opening remarks. A moderate Democrat from Wisconsin, he had made a fortune founding and running a chain of grocery stores and department stores that bore his name, and was currently the owner of the Milwaukee Bucks basketball team. He was nearing the end of his first term in the Senate, facing an election the following November.

Senator Herbert Kohl: Today is the first day of Hanukkah, and we have already begun the Christmas season. It is a time when we think about peace on earth and goodwill toward all people, and about giving gifts to our friends and loved ones, but it is also a time when we need to take a close, hard look at just what it is we are actually buying for our kids. That is why we are holding this hearing on violent videogames at this time.

Senator Joseph Lieberman, a Democrat from Connecticut, had a more conventional political background than his colleague. A lawyer by education, he had first been elected to his state’s Senate in 1970, then gone on to to serve as its attorney general for six years in the 1980s. Like Kohl, he belonged to the more moderate — i.e., conservative — wing of his party, and like him was facing his first reelection campaign as a United States Senator the following November.

Senator Joseph Lieberman: Thank you very much, Senator Kohl. It’s a privilege to co-chair this joint hearing with you. You’ve been out front protecting our children, and occasionally protecting the rest of us from them, in terms of their ability to obtain guns.[1]Kohl was a noted proponent of commonsense gun control, especially among minors.

Every day, the news brings more images of random violence, torture, and sexual aggression right into our living rooms. Just this week, we heard the dreadful story of a young girl abducted from a slumber party in her own home and then found dead. A man on a commuter train begins coldly and methodically to fire away at innocents on their way home, killing five people and injuring many others.

Violent images permeate more and more aspects of our lives, and I think it’s time to draw the line with violence in videogames. The new generation of videogames contains the most horrible depictions of graphic violence and sex, including particularly violence against women. Like the Grinch who stole Christmas, these violent videogames threaten to rob this holiday season of its spirit of goodwill. Instead of enriching a child’s mind, these games teach a child to enjoy torture. For those who have not seen these so-called “games” before, I want to show you what we’re talking about. What you’re about to see are scenes from two of the most violent videogames.

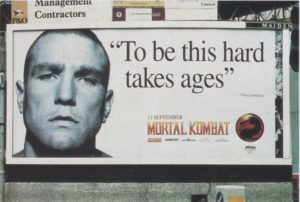

First we have Mortal Kombat, which is a martial-arts contest involving digitized characters. When a player wins in the Sega version of the game, the so-called “death” sequence begins. The game narrator instructs the player to “finish” — I quote, “finish” — his opponent. The player may then choose a method of murder, ranging from ripping the heart out to pulling off the head of the opponent with spinal cord attached. A version made by Nintendo leaves out the blood and decapitation, but it is still a violent game.

First, the Sega version.

And this is a brief sequence from the Nintendo version.

This version does not have the death sequences, and instead of red blood spurting out there’s… well, there’s some other liquid.

The second game is Night Trap, a game set in a sorority house. The object is to keep hooded men from hanging young women from a hook or drilling their necks with a tool designed to drain their blood. Night Trap uses actual actors and attains an unprecedented level of realism. It contains graphic depictions of violence against women, with strong overtones of sexual violence. I find this game deeply offensive and believe that it simply should be taken off the market now.

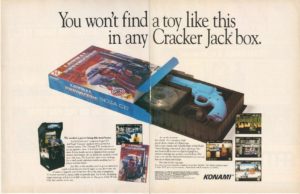

But these games are just the beginning. Last Wednesday in fact, as we were announcing our intention to hold this hearing, a videogame maker was announcing the release of a brutal videogame called Lethal Enforcers.[2]Konami’s Lethal Enforcers, a light-gun-based shooting-gallery game, was, like Mortal Kombat, one of the big arcade hits of 1992, and was likewise now coming home on consoles and computers.

This gun, called the “Justifier,” is the handheld implement with which you play the game by shooting at the screen. The more successful you are, the more powerful the gun becomes.

CD technology is also making sexually explicit videogames available. We have no way of keeping these games out of the hands of kids. Next on the horizon are videogames which are going to come to our TV screens over cable channels.[3]The dream of streaming videogame content in the same way that one streams television programs was an old one already by this point, dating back at least to the beginning of the previous decade. Despite many bold predictions and more scattershot attempts at actual implementation, it’s never quite come to pass in the comprehensive way that seemed so well-nigh inevitable in 1993.

Just a short while ago, some members of the videogame industry announced their intention to create a voluntary rating or warning-label system.[4]Sega had actually rolled out its own content-rating system just before the release of Mortal Kombat in September of 1993. Shortly thereafter, Sega and Nintendo, feeling the heat not only from Washington but from such powerful entities as California’s attorney general, did indeed agree to work together on a joint rating system — an unusual step for two companies whose relationship had heretofore been defined by their mutual loathing. On the very morning of this hearing, most of the rest of the video- and computer-game industry signed on to the initiative. I am pleased that the videogame industry recognizes there is a problem here. A credible rating system will help parents determine which videogames are appropriate for children of different ages. But I must say here that creating a rating system is, in my opinion, the very least the videogame industry can do, not the best they can do. It would be far better if the industry simply kept the worst violence and sex out of their games.

I have three major concerns as the industry develops a rating system. First, there are questions about the system itself. Who will do the rating? Will all manufacturers participate? How many age-specific ratings will there be? Will the industry spend money to inform parents about the meanings of the ratings? Second, a rating system must not be perverted into a cynical marketing ploy to attract children to more violent games. We must not allow the industry to trumpet a violent rating as a selling point. Third, the industry must work to enforce whatever rating system it creates. It should consider licensing agreements and contracts which specify that ratings will be clearly visible in any advertising and understandable by parents and consumers. Distributors, including video-rental stores and toy stores, should face some kind of penalty from manufacturers if they sell or rent to children below the minimum ages in the ratings.

Even if all of these concerns with a rating system are addressed, the videogame industry in my opinion will not have done as much as it should do to avoid creating more violence in our already too violent society. The rating system must not become a fig leaf for the industry to hide behind. They must also accept their responsibility to control themselves and simply stop producing the worst of this junk. The videogame industry has not lived up to their responsibility to America’s parents and children. I hope they will do so in the coming months, at worst by developing a credible and enforceable rating system, and at best by taking the worst games or the worst parts of those games off the market. If the violence and sex don’t come out of the games, parents should be able to keep the games out of their homes.

Senator Kohl: Thank you very much for that, Senator Lieberman. I’d like to briefly outline the major issues as I see them.

First, I believe the announcement by most of the videogame industry that they are committed to a rating system indicates that we’ve already changed the terms of the debate. Simply put, we are no longer asking whether violent videogames may cause harm to our children. Clearly they can, or the industry would not be willing to rate its own games so that young kids cannot obtain them.[5]The body of psychological research on the subject was — and is — nowhere near as clear-cut as this formulation implies. And the industry was, of course, motivated to implement a voluntary rating system by fear of government action rather than a sudden conviction that its products could indeed be harmful to children. The question now is just what restrictions we need to put in place and who should do it. In a sense, then, this hearing represents a window of opportunity for the videogame industry. I’ve spent the bulk of my adult life in business, and I know that if Nintendo and Sega, who together control 90 percent of the market, make the development and enforcement of a meaningful rating system a top priority, it will happen — quickly, voluntarily, and without chilling any First Amendment rights.

Second, let me say that I share Senator Lieberman’s outrage at the excerpts that we have just viewed. Mortal Kombat and Night Trap are not the kind of gifts that responsible parents give. Night Trap, which adds a new dimension of violence specifically targeted against women, is especially repugnant. It ought to be taken off the market entirely, or at the very least its most objectionable scenes should be removed.

But those games are only two examples. Senator Lieberman mentioned another videogame called Lethal Enforcers, which comes with an oversized handgun called the “Justifier.” This game teaches our kids that a gun can solve any problem with lethal force. Sometimes the player hits innocent bystanders. In that case, blood splatters to the ground, but what the heck, bystanders need to learn to get out of the way. Make no mistake: Lethal Enforcers is aimed at young kids. The lede of the ad says, “You won’t find a toy like this in any Cracker Jack box!” Well, I hope not.

What a cynical, irresponsible way to market a product. I find its glorification of guns to kids to be highly offensive, coming on the heels of our long battle to enact the Brady Bill and less than a month after Senator Lieberman and I passed a bill to take handguns away from minors.[6]Passed on November 30, 1993, the Brady Bill was a landmark piece of gun-control legislation which mandated that all prospective purchasers of a gun must first pass a background check and then wait five days to take delivery of their weapon. At the very least, this game sends a tremendously reckless message, and turns any effort to discourage youth violence completely on its head.

We all know that there are many causes of the violence that plagues our cities and increasingly our suburbs and small towns: broken families, poor education, easy access to firearms, drugs, the lists goes on and on. Certainly violent videogames and TV violence have become a significant part. We cannot become paralyzed by the multiplicity of causes or the magnitude of the challenge. We need to make every effort to reduce this culture of carnage, and we need to make that effort now — because these games are going to become even more sophisticated and persuasive. Experts can debate whether entertainment violence causes brutality in society or merely reflects it, but there should be no dispute that the pervasive images of murder and mayhem encourage our kids to view violent activity as a normal part of life, and that interactive videogame violence desensitizes children to the real thing. Our children should not be told that to be a winner you need to be a killer. That subtle but menacing message pollutes our society.

I’d like to call now upon my esteemed colleague Senator Dorgan.

Senator Byron Dorgan, Democrat from North Dakota, worked briefly in the aerospace industry before becoming tax commissioner of his state in 1968 at the age of just 26. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1980, going on to serve six terms there before being elected to the Senate in November of 1992.

Senator Byron Dorgan: I wanted very much to be here because I think this is a very important issue. It has been quite a leap from Pac-Man to Night Trap. Violence in videogames is a close cousin to violence on television. I know there are critics of these hearings; these critics are similar in my judgment to those who are still saying there’s no evidence that cigarettes cause cancer. There’s no evidence, they say, that violence in videogames affects our children. Have they lost all common sense? Of course it affects our children, and it affects our kids in a very negative way.

About two months ago, I saw the videogame Night Trap for the first time. It is a sick, disgusting videogame in my judgment. It’s an effort to trap and kill women.[7]The player’s objective in Night Trap, of course, is not to trap and kill women but rather to protect them from others who seek to do so. Shame on the people who produce that trash. It’s child abuse in my judgment.

I know some people will say we are trying to become the thought police. That is not my intention, but we have to take some basic responsibility in this country to protect children. Those who have children understand that they deserve protection. Certain things are appropriate for them and certain things are not. An author once said that 100 years from now it won’t really matter how big your income was or how big your house was, but the world might be a different place because you were important in the life of a child. Maybe our efforts will be important in the lives of children, and will make improvements in this world. I hope so.

Senator Kohl: We’d like to call our first panel now, composed of representatives from academia and education, and also concerned citizens. You may each give a statement.

Parker Page was the head of the Children’s Television Resource and Education Center, an advocacy group whose concerns about violent content on children’s television had recently spread to videogames.

Parker Page: Parents and educators tell us that they are increasingly worried about the effects of violent videogames on children. But do their worries merit national attention? In a country which is grappling with an epidemic of real-life violence, should we bother ourselves with kids’ leisure-time activities like playing videogames? We think the answer is yes.

For, while the impact of violent videogames is still open to debate, early studies as well as decades of television research warn us of possible consequences, especially for young children. The TV research is conclusive: violent screen images have their own special effects. Children who watch a steady diet of violent programming increase their chances of becoming more aggressive toward other children, less cooperative and altruistic, more tolerant of real-life violence, and more afraid of the world outside their homes. The case against videogame violence is not nearly so clear-cut for one simple reason: there hasn’t been enough research.

In the last ten years, only a handful of published reports have explored the effects of videogames. Moreover, the few experimental studies that have been conducted relied on crude cartoon-like videogames produced in the early 1980s, archaic by today’s standards of technological wizardry. Even so, several of the initial videogames studies suggest that there is a link between violent videogames and children’s aggression. For example, research studies have shown that, at least in the short term, children who play violent videogames are significantly more aggressive afterward than children who play less violent videogames. All this research is limited and it’s dated. The overall trends, however, must give us cause for concern as we approach virtual reality.

Mortal Kombat is the latest in a new generation of videogames that allow software designers to combine high levels of violence with fully digitized human beings. While these lifelike characters may make the videogame more thrilling, TV research sends us a warning that the more realistic the images of violence, the more likely they are to influence young children’s behavior and attitudes. Unfortunately, there is no timeout for millions of American children who are daily immersed in videogame violence and bombarded by videogame advertising. Therefore we recommend the following:

We recommend that the federal government fund independent research projects and disseminate their findings in order to shed additional light on the effects of videogames and other emerging interactive media. We recommend that the videogame industry provide parents with more accurate and detailed product information than is currently available, make a commitment to advertising strategies and marketing that reinforce the rating system rather than undercut it, and pursue an industry-wide agreement to put a cap on violence. Videogames that allow young players to participate in heinous acts of cruelty and inhumanity should not exist, regardless of profits.

Having made these recommendations, it’s important to underscore that parents must still shoulder the major responsibility for guiding their children’s entertainment activities. We recommend strongly that parents become actively involved in helping their children make videogame choices that reflect each family’s values, that they take seriously the videogame warning labels and content descriptions that are available, and that they make videogame playing truly interactive by setting up time limits, by substituting less violent games, and by making game-playing a social rather than an isolating activity.

In conclusion, I believe that this national attention on videogame violence affords us a rare opportunity to avoid the enormous time lag between the TV-violence research findings and public awareness. We have a chance to lower the impact of videogame violence on children’s lives sooner rather than later. I hope that all of us will seize the moment.

Eugene Provenzo was (and is) a professor of pedagogy at the University of Miami. He had recently published the book Video Kids: Making Sense of Nintendo.

Eugene Provenzo: Most adults pay relatively little attention to videogames. Although I’ve been studying toys, games, and the culture of childhood for nearly twenty years, it wasn’t until a neighbor came up to me three years ago and asked me what I thought of videogames that I began to consider their implications. What I found shocked me.

During the past decade, the videogame industry has developed games whose social content has been overwhelmingly violent, sexist, and racist, issues that I’ve addressed extensively in my research. For example, in Video Kids I explored the 47 most popular videogames in America. I found that 40 had violence as their main theme, and thirteen included scenarios in which women were kidnapped and had to be rescued — i.e., the idea of women as victims. Although men were often rescued in games too, they were never rescued by women. Videogames have a marked tradition of extreme violence which is also combined with gender discrimination.

Some of my more recent research suggests that videogames are evolving into a new type of interactive medium — participatory or interactive television is what I’m calling it. This new CD-ROM-based videogame technology represents a major evolutionary step beyond the simple graphics of the classic Space Invaders arcade games so popular fifteen or twenty years ago, or even the tiny animated cartoon figures that we see in the Nintendo system. When you combine CD-ROM-based technology, which allows you to have digitized films in the computer, with virtual-reality technologies like Sega’s Activator, which allows you to literally have your movements sensed — punching, hitting, kicking, all translated into the computer — you have something remarkable — a remarkably new and different type of thing. I want to make it very clear that we are dealing with something different, a new type of television.

I believe that the remaining years of this decade will see the emergence and definition of this media form in the same way that the 1940s and 1950s saw television emerge as a powerful social and cultural force. If the videogame industry is going to provide the foundation for the development of interactive television, I think that citizens, parents, educators, and legislators have cause for considerable concern and alarm.

We are at the threshold of a new generation of interactive television. While I believe as an educator that this technology has wonderful potential, I’m also convinced that if we continue using it without addressing the full ramifications and significance of the social content of videogames, we’ll be doing a serious disservice to both our children and our culture.

Dr. Robert Chase was the vice-president of the National Education Association, the largest labor union in the United States; its ranks included more than 2 million schoolteachers and other education professionals.

Robert Chase: I join Senator Lieberman in calling for the producers of electronic games to live up to their responsibilities in helping to raise a generation of children free from violence. It is disheartening that there is even a demand for games that are explicitly violent and graphically sexual.

The first line of defense against the wide distribution of such games remains the family. All parents must assume for themselves the responsibility to raise their children with values of respect and decency and a sense of limits about what is appropriate behavior. I don’t wish anyone to dictate to me what is appropriate for my daughters to see or to say or to do, any more than I would presume to tell you what is appropriate for your sons and daughters. However, I hope we share a commitment to providing parents with appropriate tools to make reasonable judgments for our children.

Electronic games, because they are active rather than passive, can do more than desensitize impressionable children to violence; they can actually encourage violence as the solution of first resort by rewarding participants for killing one’s opponents in the most grisly ways imaginable. The guidelines that now exist for films should be extended to electronic games. We can and must establish a system of parental notification about the graphic sexual or violent materials contained in some videogames.

Marilyn Droz represented the National Coalition on Television Violence.

Marilyn Droz: I’ve been a parent for sixteen years, a wife for twenty years, a teacher for 23 years, and a woman since the day I was born. Let me tell you, in all of the hats I wear, I find the games we’ve seen today extremely offensive, and the only words I can say to the manufacturers and shareholders of the companies are, “Shame on you!” I think they really should stop and think about what they’re doing. I mean, how would you like to have a teenage daughter go out on a date with someone who’s just played three hours of one of those games?

The word “toy” comes from a Scandinavian word meaning “little tools.”[8]This is, at best, an extremely dubious etymology. The Danish word “tøj,” which is pronounced like the English “toy,” actually means clothing. While “værktøjer” means tools, there is no single word for “little tools”: one would need to say “små værktøjer” to get that concept across. The Danish word for toy, on the other hand, is “legetøj.” If the English word descends from the Scandinavian languages at all, it is almost certainly an abbreviated version of this word. Even this, however, is by no means a firmly established etymology. That’s very appropriate because play is the work of children; it’s what prepares them for the future. The technology of today is phenomenal, and it’s going to have the power to prepare our children for a future that we are not able to understand ourselves, a future that’s well worth looking for — if we can get the videogame industry to change some of their values.

When computers first came out, videogames were played equally among boys and girls in the classroom; there was equal time.[9]I have seen no evidence in my own research that there was ever a time when videogames were as popular among girls as boys. Now, it seems boys are comfortable with the technology. Videogames are geared to boys. Fifty percent of our children are losing the value of interactive technology. We are losing a generation of women. Our research indicates that girls are very offended by the lack of games for them. They feel inferior. It’s very easy to determine which are the girl games and which the boy games; girl games are the ones with the fluffy little bunnies. Playing videogames has become a boy thing. Girls are being trained to dress Barbie dolls, while boys are being trained in technology. This has to change. As a mother, as a parent, as a woman, and as an American citizen, I am stating that this needs to change.

Games have confused children’s desire for action with violence. Children want action, they want excitement; they do not need to see the insides of people splattered against the wall. We all work so hard to raise our children well, and our efforts are undermined by videogames, which teach them that the only way to solve problems — the quickest, most efficient way — is to kill ’em off. There are very few women characters with any control or power. Videogames tell our girls that they can be either sex objects or victims; that’s their choice. The very few women who have any kind of power are built with iron body parts, or they can blow a kiss of death. Once again, we’ve got sex and violence. This has to stop.

Almost everything we purchase nowadays has regulations. We have regulations saying that physical toys cannot contain parts that are easy to swallow. Well, I’m finding this violence difficult to swallow. Thank you for bringing this issue before the public.

Eugene Provenzo: I think another thing to point out here is that the psychological studies of the effects of videogames are all from the early 1980s. They’re based on arcade games like Space Invaders, which are highly depersonalized. There are four generations of videogames. There’s Pong, there’s Space Invaders, there’s Nintendo with its cartoon figures, and we’re into the next stage right now, which is Night Trap-type games. And there’s a new stage after this, which is the combining of this with virtual-reality devices. We’re beginning to move into that, where kids can physically participate in the violence. We need to do more studies; we don’t know yet what the results of playing a game like Night Trap are. But we can make some guesses.

Parker Page: Yes, there needs to be a body of upwards of 100 studies before the research on videogames will be as definitive as the research on television. However, given the similarities with television watching, I would be amazed if we don’t find either similar or stronger effects.

Eugene Provenzo: There’s a parallel issue that I think is relevant here in terms of violence against women. There is a new field emerging called cybersex; that’s not a joke. What it amounts to is pornography on CD-ROM. You can dial up what you want — a blonde, a redhead, a brunette, male or female — then do what you want to them. Imagine that getting into the hands of a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old who’s had no sexual experience. And they play these games for three or four years, then they finally meet a real woman on a date. That’s very scary. Look at the portrayal of the women in Night Trap. There are obvious sexual overtones there.

Parker Page: There are some folks who believe that violent videogames can drain away aggression — that they can have a cathartic effect, making kids less violent. That’s a great theory, but it makes for very lousy research. The research in the area of TV violence points in the exact opposite direction.

Senator Lieberman: Dr. Provenzo, you state in your book that videogames are not only violent and sexist but also racist. Can you give a few examples?

Eugene Provenzo: Sure. In interviews with children, they talked about the ninjas as being bad. And then you ask them who the ninjas are, and they said, “The Japs and the Chinese.” It turns out that they perceive Asians as being extremely violent, as being dangerous, as being evil. There is homophobia operating, in terms of how certain types of women are portrayed. It’s subtle and hard to get at sometimes, but I think it presents a relatively disturbing world.

I interviewed large numbers of girls. They said, “I don’t like videogames. I don’t like computers. I think I would like them, but I don’t like what they’re about.” The industry people often argue that videogames are children’s introduction into the culture of computing. We’re discriminating against girls by providing them with these consistent negative images. They get turned off of computers. We’re driving them away from these tools of the 21st century that they need to master. I think that’s very objectionable.

Senator Dorgan: Sega states in five mitigating points responding to the controversy over Night Trap that it was meant to be a satire of vampire films, and that the controversial scene we’ve just seen is displayed only when the player loses. Does that make you feel any better?

Marilyn Droz: Oh, it makes me feel a lot better that if you’re a loser you’re dead.

Eugene Provenzo: At the beginning of Night Trap, your commander looks you straight in the eye and says, “If you don’t have the brains or guts for this mission, then give control to someone who does.” A fascist military type looks at you and essentially says, “If you’re not man enough to do this, forget it! You don’t deserve to play this game!”

I’d like to make a suggestion that I don’t think is that difficult to implement: I’d like to see violence portrayed accurately. I would like to see a videogame where, if you punch someone viciously, they don’t get up and take another punch. Children don’t understand what guns and hitting do. They don’t get that communicated to them. They think that guns aren’t that serious. They don’t understand that when a bullet goes through your leg, you may not walk again, you may lose your leg.

Senator Lieberman: We thank all of you for coming. Let me now call the second panel.

Howard Lincoln is a legendary figure in the history of videogames. Along with Minoru Arakawa, he is widely and justly recognized for resurrecting the videogame console in North America in the form of the Nintendo Entertainment System. At the time of this hearing, he had the title of senior vice president of Nintendo of America, but he effectively ran the multi-billion-dollar branch as a co-equal with Arakawa, its official founder and president. Famous or infamous, depending on one’s point of view, for his take-no-prisoners approach to business, his fingerprints were on every aspect of Nintendo’s American strategy.

Howard Lincoln: Nintendo is just as concerned about the issue of violence in videogames as anyone in this room. Of course, every entertainment executive tells Congress that. But Nintendo can back it up.

In the mid-1980s, when Nintendo entered the videogame business in this country, the issue of violence in videogames was not in the public’s eye. But just like today, there was a computer-software industry selling videogames, and some of these games contained excessive violence and pornographic material. We didn’t want Nintendo’s name associated with this kind of product. Even then, we were concerned about game content. So in 1985, when we launched our first Nintendo home-videogame system, we make a conscious decision not to allow excessively violent, sexually explicit, or otherwise offensive games on it. We incorporated a patented security chip in all Nintendo hardware and software; this enabled us to review and approve the content of all videogames played on Nintendo’s hardware, whether made directly by Nintendo or by one of our approximately 70 third-party licensees.[10]This chip also allowed Nintendo to assure that they collected a royalty from each and every game that was sold for their console — something Atari wouldn’t or couldn’t do during the first videogame craze. Nintendo has guidelines which control game content, and we’ve applied these to every one of the more than 1200 games released to the marketplace by Nintendo and its licensees. These guidelines prohibit sexually suggestive or explicit content; random, gratuitous, or excessive violence; graphic illustration of death; excessive force in sports games; ethnic, racial, national, or sexual stereotypes; profanity or obscenity; and the use of illegal drugs. Over the last eight years, these guidelines have kept an enormous amount of offensive material out of American homes.

Of course, our guidelines are not perfect, and may not answer everyone’s concerns. After all, videogames are a form of entertainment covering everything from education to the martial arts. But I must say that we have made a good-faith effort to keep offensive material off our game systems, and we intend to continue applying our game guidelines in the future.

In the past year, some very violent and offensive games have reached the market. Of course, I’m speaking about Mortal Kombat and Night Trap. Let me state for the record that Night Trap will never appear on a Nintendo system.[11]It wouldn’t have been technically feasible to release a Nintendo version of Night Trap because the company had no CD drive in its product catalog. A game which promotes violence against women simply has no place in our society.

Let me turn to Mortal Kombat. To meet our game guidelines, we insisted that one of our largest licensees, Acclaim Entertainment, remove the blood and death sequences present in the arcade version before we would approve this game. We did this knowing that our competitor would leave these scenes in, and with full knowledge that we would make more money if we included the offensive material. We knew that we would lose money by sanitizing Mortal Kombat, but sanitize it we did. We have been criticized by thousands of young players for insisting that the death sequences be removed from this game.

Senator Lieberman: So, people actually complain that they can’t have the more violent game on the Nintendo system?

Howard Lincoln: That’s correct. Letters and phone calls say, “Leave in the violence! You’re censoring!”

We share the public’s growing concern with violence. Nintendo will do everything it can to develop a workable game-rating system. But a rating system is no substitute for corporate responsibility. Rating games will not make them less violent. Only manufacturers can do that by keeping outrageous games like Night Trap off the market.

Bill White was a vice-president of marketing and communications at Sega of America. He had left Nintendo to join what everyone there regarded as the enemy camp less than six months before. The bad blood between Lincoln and White — a proxy for the bad blood between the arch-rival corporate entities they represented — was palpable throughout the hearing.

Bill White: I want to address three key points. First, the fallacy that Sega and the rest of the digital interactive-media industry only sell games to children. In fact, our consumer base is much broader. Second, the efforts which Sega has already made to provide parents with the information they need to distinguish between interactive-media products which are appropriate for young people and those which are not. And third, the efforts which Sega is currently making to gain the cooperation of all interactive-media companies to develop an industry-wide rating system.

In recent days, the glare of the media spotlight on this issue has resulted in a number of distorted and inaccurate claims. The most damaging of these in my view is the notion that Sega and the rest of the digital-interactive industry are only in the business of selling games to children. This is not the case. Yes, many of Sega’s interactive-video titles are intended and purchased for young children. Many other Sega titles, however, are intended for and purchased by adults for their personal entertainment and education. The average Sega CD user is almost 22 years old, and only 5 percent are under the age of thirteen. The average Sega Genesis user is almost nineteen years old, and fewer than 30 percent are under the age of thirteen. There truly is something for everyone in our software catalog, and the variety of available software is multiplying each day. Interactive media should be treated no differently than the television, motion-picture, recorded-music, or publishing industries. Attempts to relegate digital interactive software to a media backwater are outdated and inappropriate. It makes no more sense to conclude today that digital interactive media is only for children than it would have, when the Gutenberg press was in its infancy, to conclude that the printed word was only for Bible readers.

Digital interactive media communicates increasingly diverse information to an increasingly diverse audience. Looking at our most recent data for 1993, action-adventure titles such as Sonic Spinball and Jurassic Park account for 40 percent of the revenue from our library. Sports titles such as NBA Action ’94, World Series Baseball, and Joe Montana Football account for 35 percent of our revenues. Fighting games such as X-Men and Eternal Champions comprise 13 percent of our revenues. Titles in the children-entertainment category such as Barney’s Hide and Seek, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, and Fun ‘N Games produce 5 percent of our revenues. Role-playing games such as Landstalker make up 5 percent of revenues. And strategy and puzzle games such as Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine constitute 2 percent of revenues.

As you can see, evolving interactive technology reaches a huge market that goes well beyond the child-oriented titles that gave the industry its start. Anything Congress might do on this front would affect a large, diverse group of consumers, young and old, in a volatile industry still in its infancy. Information, not regulation, is the appropriate policy.

Last September, Sega completed its implementation of a comprehensive guidance program which we began developing over a year and a half ago. It is a three-pronged approach designed to help parents determine the age-appropriateness of different interactive-video software. It includes a rating system, a toll-free hotline, and an informational brochure. Building on the motion-picture industry’s model, the Sega rating system applies one of three classifications to each interactive program released by Sega: GA for general audiences, MA-13 for mature audiences age thirteen and over, and MA-17 for titles not suitable for those under age seventeen. A Videogame Rating Council, created by Sega and consisting of independent experts in the areas of child psychology, sociology, cinema, and education, is responsible for evaluating each game and giving it the appropriate rating classification. I want to emphasize that this is an independent council. Even though it takes considerable time to evaluate each product, individual council members are paid only a small honorarium for each game they rate.

And now we and others in this industry are prepared to take the next step. This morning, a number of interactive-video companies and some of the nation’s leading retailers announced their plan for creating an industry-wide rating system. The coalition committed to this effort includes Atari, 3DO, Wal-Mart, Sears, Toys ‘R’ Us, Blockbuster Video, and videogame publishers representing over 90 percent of the market. The goal is to develop and implement a rating system that enjoys widespread support and voluntary participation throughout the industry.

There is every reason to be optimistic about the industry’s ability to voluntarily provide parental guidance, but we ask that you treat digital interactive media as you have treated other media such as the motion-picture industry: give parents the power to choose what’s right for their kids, but don’t tell adults what’s right for them.

Ileen Rosenthal was the general counsel of the Software Publishers Association. Formed in 1984, when videogame consoles seemed to most to be a fad of the past and personal computers the exclusive future of interactive entertainment, the traditionally computer-focused SPA was not an overly prominent voice in the world of Nintendo and Sega, although the latter was a member. Indeed, their biggest concern for years was a problem that effectively didn’t exist on the consoles, thanks to the latter’s use of cartridge-based, read-only media: software piracy, which the SPA opposed with a long-running media campaign whose tagline was “Don’t Copy That Floppy!” The presence of a representative of the SPA at this landmark hearing is often overlooked — as, for that matter, Rosenthal’s presence apparently was to some extent by the people who called the hearing; in marked contrast to the sustained grilling delivered to Howard Lincoln and especially Bill White, she would receive just one perfunctory yes/no question from the senators after making her opening statement.

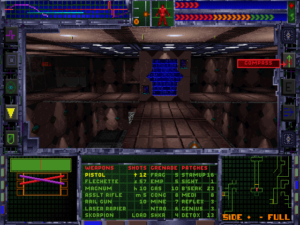

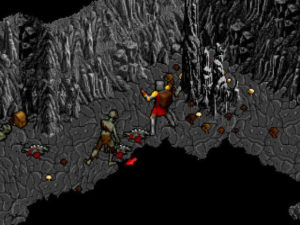

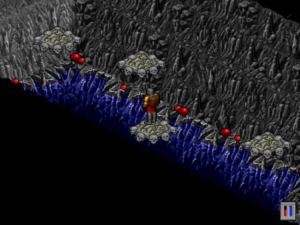

While they made up only about 10 percent of the digital-gaming market in 1993, computer games were hotbeds of innovation, being in many cases more complex and aesthetically ambitious than their console counterparts, with a customer demographic that skewed older even than that of Sega. The people holding the hearing would doubtless have found plenty on personal computers to be outraged about, had they only looked: CD-ROM-based “interactive movies” like Voyeur were far more sexually suggestive than the likes of Night Trap, while action games like id Software’s Wolfenstein 3D, which were now regularly bubbling up from the rough-and-ready shareware underground, were at least as violent as Mortal Kombat. But, thanks to their smaller and older player base — and doubtless thanks to the fact that personal computers tended to be installed in private bedrooms and offices rather than public living rooms — the content of computer games would largely escape serious mainstream scrutiny for years to come. Not until the Columbine High School Massacre of 1999 was carried out by a pair of rabid DOOM fans would computer games find themselves the focal point of a controversy over violent media. (In one of those delicious concordances which history delivers from time to time, id Software would upload the first episode of DOOM to the shareware servers that were to host it about eight hours after this hearing wrapped up.)

Ileen Rosenthal: As the videogame industry has grown, we are finding that some products have begun to incorporate violent and explicit themes. It is inevitable that some of these products will find their way into the hands of children. However, in our attempt to protect our children from those games which contain violent and mature themes, we must not lose sight of the fact that the vast majority of games are appropriate for children, and have the potential to develop many important and socially desirable skills. For example, it is a fact that children who are considered to have short attention spans can focus for hours on a videogame, discovering rules and patterns by an active and interactive process of trial and error. Surely the potential of this medium for bettering our children’s thinking skills is enormous. Even in the literature of Dr. Page’s organization, it asks, “Is there anything good about playing videogames?” The answer: “Sure there is. Like puzzles, board games, and other forms of interactive entertainment, playing videogames can help kids relax, learn new strategies, develop concentration skills, and achieve goals. If they are playing with others, it can also be a great time for socialization.”

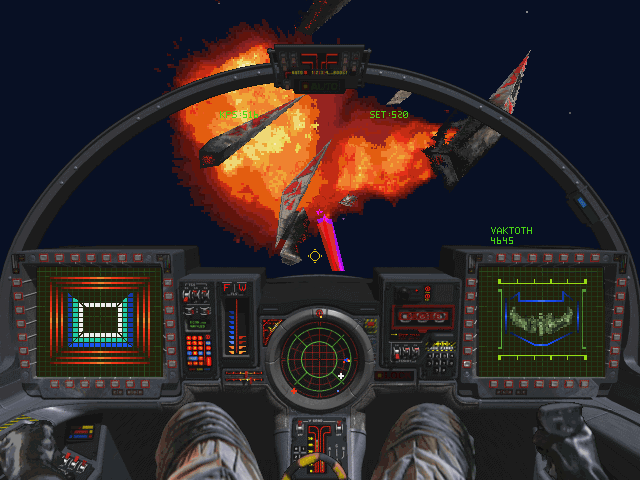

Each month, SPA puts out a list of the top-selling software. In September of 1993, most of the games on it had nothing to do with violence: Microsoft Flight Simulator; Wing Commander: Privateer, an outer-space role-playing game; Front Page Sports: Football; X-Wing; Lands of Lore, a fantasy role-playing game; SimCity.[12]Rosenthal doesn’t make it clear here that, in keeping with the computer focus of the SPA, this list includes only games for computers, not consoles. Further, only games that were sold as boxed products in retail stores are included; the list misses entirely the vibrant shareware scene, where games like id’s Wolfenstein 3D were already pushing the envelope on gore and violence at least as much as Sega. Thus it provides a somewhat distorted view of the overall state of gaming even on computers. I want to point out that computer-based games have traditionally been targeted to an older audience than the original videogames.

Dawn Wiener, president of the Video Software Dealers Association, and Craig Johnson, a past president of the Amusement and Music Operators Association, also delivered prepared statements. But they largely echoed Bill White’s statement that the industry ought to be allowed to regulate itself — it’s clear that a degree of message coordination went on prior to the hearing — and they did so in fairly milquetoast fashion at that. So, I’ve chosen to omit their statements here.

Senator Lieberman: Mr. White, let me go right to the heart of the matter with you. Mr. Lincoln just said that Night Trap has no place in our society. Why don’t you agree? Why don’t you pull Night Trap off the market?

Bill White: The interactive-media industry has grown tremendously, and children represent only a portion of the audience that we serve. Night Trap was developed for an adult audience. Sega’s independent rating council labeled it MA-17: “not appropriate for children.”

Senator Lieberman: But do you think that stuff is appropriate even for an adult audience? A provocatively dressed woman is brutally attacked. A lot of the products your company produces are great. Why do you need to produce this stuff, whether for adults or kids?

Bill White: If you saw only the violent or gory scenes from Roots or Gone with the Wind out of context, you might conclude that they’re horrible films. In reality, they aren’t. You’ve picked out a particular segment of the game. A winning effort in Night Trap saves the women. Your job as the player is to identify the villains and to trap them. This game is appropriate for adults who choose to entertain themselves with it.

Senator Lieberman: And if you’re a bad player?

Bill White: If you’re a bad player, you will see that scene.

Senator Lieberman: You have a long way to go to convince me that you’re raising anyone’s values or reducing their aggression, particularly toward women.

Bill White: We agree with much of what the earlier panel said. We believe that more research is necessary to conclude what effect games can have on both adults and children.

Senator Lieberman: Then why don’t you wait until the research is done?

Bill White: Because we believe that adults can make the choice for themselves of whether that game is right or wrong for them.

Senator Lieberman: I have here a recent Sega brochure. You’ve got Night Trap alongside Joe Montana Football and Spider-Man Versus Kingpin and Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective. Is this responsible advertising?

Bill White: We’ve taken the first step toward an industry-wide rating system. Just as the motion-picture industry produces films for adults as well as children, the interactive-entertainment industry will continue to produce products that are appropriate for both. We would like to see better enforcement at retail. We would like to see the ratings prominently displayed in advertising.

Senator Lieberman: You agree, then, that this brochure is irresponsible?

Bill White: That was developed prior to our full implementation of our rating system.

Senator Lieberman: If you’ve updated your rating system, I hope that you’ll also update your promotional system.

I want to show an advertisement for Mortal Kombat for Sega. This game is rated MA-13, not suitable for children under thirteen. But just watch this advertisement, and tell me whether it doesn’t encourage children under thirteen to buy Mortal Kombat.

The nerd that became a hero by buying Mortal Kombat looks to me to be under thirteen. What can you do to prevent boys under thirteen from seeing this ad and deciding that their masculinity and freedom from bullies will be determined by whether they can play this game?

Bill White: That advertisement is directed to teens, not to children. I can’t comment on the age of the cast because I just don’t know. The intent of our rating system is to take a first step. We’re proud of that step. We don’t believe it’s perfect, but we do believe that more information is the answer, not government regulation, and certainly not censorship.

Senator Lieberman: I agree with you. The rating system is only a first step. And it’s a fig leaf to cover a lot of transgressions if you don’t enforce it better and, I hope, apply a little bit of self-control to yourselves. Is that ad placed on children’s shows?

Bill White: No, that ad would not be placed on a children’s show. We buy television time directed toward teenagers and time directed toward children. That ad was not approved for children’s television.

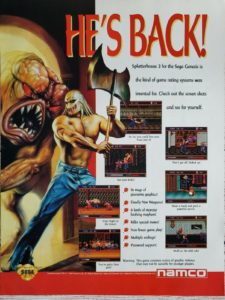

Senator Lieberman: I have an ad here from GamePro magazine. At the top it says, “He’s back! Splatterhouse 3 is the kind of game ratings systems were invented for!” At the bottom, it says that it “includes deadly new weapons, six levels of monster-bashing mayhem, and killer special moves!” Doesn’t that kind of advertisement make a mockery of your rating system?

Bill White: I haven’t seen this advertisement. We have no control over what an independent publisher says about our rating system, any more than the motion-picture industry can control what an individual studio says about its rating system.

Senator Lieberman: But wouldn’t you agree, having seen it now, that that makes a mockery of your rating system? I can’t believe that’s what you want.

Bill White: We want to take the next step. That’s why we’ve worked around the clock for the past two weeks to establish an industry coalition that will develop an industry-wide rating system.

Senator Lieberman: Well, there’s a lot of work to do, to put it mildly.

Mr. Lincoln, I appreciate that you’ve been self-regulating to some degree, and I also appreciate that you’ve accepted the idea of a rating system. Even though your games are less violent and less graphically sexual, there is violence in them. Dr. Provenzo feels that there is a lot of violence in the Nintendo products. Can assure us that everyone involved with Nintendo is committed to the rating system?

Howard Lincoln: I can certainly do that. But the point I’m making is that a rating system just doesn’t go far enough. We have to get our hands on the game content. We’ve been doing that, although, like anything, it’s not perfect.

I can’t sit here and allow you to be told that somehow the videogame market has been transformed from children to adults. It hasn’t been — and Mr. White, who is a former Nintendo employee, knows the demographics as well as I do. Further, I can’t let you be subject to this nonsense that this Sega Night Trap game is only meant for adults. There was no rating on this game at all when it was introduced. Small children bought it as Toys “R” Us, and he knows that as well as I do. They adopted the rating system when they started getting heat about this game. But today, as sure as I’m sitting here, a child can go into a Toys “R” Us and buy this product, and no one will challenge him.

I agree that everything Nintendo has done hasn’t been perfect. As a matter of fact, when I came into this hearing this morning, I saw that you have an advertisement for one of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System games. It says, “They’ve got a bullet with your name on it!” I phoned our head office and found out that licensee put out that advertisement without our consent, without our review, and without our permission. If that advertisement is not withdrawn, that company is in breach of its license agreement. We do have the ability and the right to control advertising by our licensees, and we take that seriously. I’d like to apologize to this committee for the fact that we slipped up. But let me tell you, when I get back to Seattle, I will call that licensee.

Senator Lieberman: Thank you for your forthrightness. Thank you for taking responsibility. You’ve shown some leadership here. You’re not perfect, as you’ve said, but you’ve been a damn sight better than the competition.

Bill White: Senator, it’s all well and good for Nintendo to say it has content guidelines. Sega has content guidelines as well. I had the opportunity to meet with your staff and show them some Nintendo games, and to compare their level of violence to the same games on the Sega platform. I’d like to show some of that comparison in order to illustrate that the guidelines Mr. Lincoln speaks of continue to allow excessive violence — without the benefit of a rating system, without the benefit of packaging that clearly states this is for mature audiences.

Senator Lieberman: Mr. White, let me just say this to you. Today, Mr. Lincoln has accepted the idea of a rating system. Nintendo had previously been self-regulating more than you. They chose not to produce Night Trap, and they have a less violent version of Mortal Kombat. You have a rating system, but I still haven’t heard you accept responsibility for regulating the content of your games. That is what’s at issue, notwithstanding the tape you’ve just shown us, which doesn’t compare in my opinion to Mortal Kombat and Night Trap.

Senator Kohl: I’d like to ask both Mr. Lincoln and Mr. White the following question. As you expand your business into the adult market, can you guarantee that children won’t see this adult product?

Howard Lincoln: No.

Senator Kohl: Mr. White?

Bill White: No, we can’t, Senator. All we can do is work with the mechanisms that are available to us.

Senator Kohl: So, there’s no way we can feel comfortable that material which some of us might feel doesn’t belong on the market at all won’t get onto the market and then be viewed by children?

Bill White: There’s an interesting difference between Sega and Nintendo here, in that we’ve moved ahead with CD technology, while Nintendo has not. They continue to focus on children. We have recognized that the interactive-entertainment market is far larger. We would like to have a rating system that will allow us to develop games for that broad array of players.

Howard Lincoln: I didn’t realize the hearing was focused on market share. I thought we were talking about regulation and violence. My colleague must think differently. Certainly the industry is moving into new territory with new technology. Nintendo, for example, will soon be coming out with a 64-bit system. Graphics are going to become much better. Unless we can get everyone in the industry to put a stop to the kind of things you’re seeing in Night Trap, we’re just deceiving ourselves.

Senator Kohl: I think it’s encouraging that you find so much to disagree with each other about. It indicates that you’re not here in a lockstep way. You’re really concerned about what the others are doing, and are worried perhaps that you’re going to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. I hope you walk away with one thought: if you don’t do something about it, we will. Senator Dorgan?

Senator Dorgan: Does anybody here have any notion how many babies will be born this year out of wedlock? No? Over 1 million, 800,000 of whom will never learn the identity of their father during their lifetime. Children are growing up without supervision, without the parents you so blithely say should supervise them. I agree that parents ought to be involved in their children’s viewing habits and so on, but the fact is, in many cases there are no parents! What do you do about those kids?

I understand that Night Trap was not rated when it was first released, and then it was rated at the MA-13 level. Is that correct?

Bill White: Once it was rated, it was rated MA-17, Senator.

Senator Dorgan: Do you consider those over the age of thirteen to be mature?

Bill White: MA-13 is appropriate for teenagers and older.

Senator Dorgan: Isn’t the word “mature” attached to that rating?

Bill White: Yes.

Senator Dorgan: So, the presumption is that those over thirteen years of age are mature?

Bill White: Yes, with parental discretion.

Senator Dorgan: Are you kidding me? What kind of rating system identifies kids of thirteen as mature?

Bill White: It’s similar to the motion-picture rating of PG-13.

Senator Dorgan: We have some responsibility to protect children. We protect them from access to alcohol. We protect them in a whole range of areas. With respect to a videogame in which a woman is grabbed by the neck with a hook, drilled in the neck with a tool, or someone grabs the heart out of a character… we ought to have just as much concern about protecting our children from that sort of trash.

Mr. White, I’ve read your written statement, and I honestly think you don’t understand what we’re talking about here. In your final point about Night Trap, you write this: “Finally, there is some research indicating a short-term, momentary increase in playful aggressive behavior after playing videogames or watching violent television programming. But there is no research indicating this has any lasting impact. In fact, quite the opposite is true.” My sense is that you just don’t get what this hearing is about. You say, “This is not for kids. This is adult entertainment.” But you and I both know that kids will have wide access to it. We need to exercise responsibility and protect those children. Profiting at the expense of America’s kids is not moral profit.

Senator Lieberman: Mr. White, in your rating system you have a category of “non-approved.” The latest version of your guidelines reads: “As always, Sega will not approve products which include material that encourages criminality of any kind.” Isn’t a game that requires kids to point a gun at the television set encouraging criminality? We’re all aware of the incredible outbreak of gun violence in this country.

Bill White: We rely on the independent rating council to make those decisions because we in corporate management are not psychologists or sociologists. They have rated that product MA-17: only appropriate for adults.

I’d also like to point out that Nintendo produces a “rapid-fire machine gun” that uses the same technology. They have no rating on that product to suggest it is for adults.

Senator Lieberman: Mr. Lincoln, what game is that for?

Howard Lincoln: This is something that can be purchased for the Super NES. It’s called the “Super Scope.” Sega’s gun is called the “Justifier.” Our gun is for target-shooting. [There is laughter in the room after Lincoln makes this statement, although it was apparently not intended in jest.]

Lethal Enforcer, the game you’re speaking of, was initially rejected by Nintendo. We told the licensee that they would have to remove the name “Justifier” and we wouldn’t approve their packaging. Because of this, that game is not yet out on Nintendo.

Senator Lieberman: I hope you’ll think again before it goes onto the market because this is about more than the name “Justifier.” That is a handgun, pure and simple. No matter what name is on it, putting it in the hands of kids gives them the wrong idea. And I must say that your Super Scope also looks like an assault weapon to me.

Pursuant to your commitment to have a rating system, would you commit to do everything in your power to ensure that the ratings are not only visible on your products but visible in their advertising?

Bill White: Yes. The ratings should be prominent in advertising. You have our commitment to that. I don’t believe that same commitment has been made by Nintendo.

Howard Lincoln: I don’t know what he’s talking about there. As you well know, we have made a commitment to the rating system. But we are concerned that a rating system by itself might just lead to an open season on more violent games. The commitment I’ll make is that we’ll be the first ones back here if what we see is just business as usual. If we’re going to have a rating system, let’s put some meat into it and enforce it.

Senator Lieberman: Ms. Rosenthal, will you make the same commitment?

Ileen Rosenthal: Absolutely. The software industry is sincerely interested in the well-being of children.

Senator Lieberman: A final question for Mr. White. In your guidelines, you say you won’t publish products which denigrate any ethnic, racial, sexual, or religious group. Obviously I think that Night Trap denigrates a sexual group, namely women. But there’s a Konami ad which talks about “fighting ninjas in Chinatown.” Obviously that’s culturally inaccurate since ninja are in the folklore of Japan, not China. But do you agree that that’s in violation of the spirit of your own guidelines?

Bill White: Senator, those guidelines refer to the games themselves, not to their advertising. And that’s not our advertisement.

Senator Lieberman: Would you include that kind of language — “fighting Ninjas in Chinatown” — in your own advertising?

Bill White: No. We strongly discourage that kind of language.

Senator Lieberman: Okay.

Senator Kohl and I are very serious about this, and intend to stay with it. I hope you’re able as an industry to come up with a rating system that addresses everyone’s concerns, but I think the best guarantee of that is for us to stick to the course we’ve set. I know there’s a tremendous market incentive here, but the best thing you can do — not only for the country but for yourselves — is to self-regulate. It will be important for the ultimate credibility and success of your business. And it’s important to the maintenance of our Constitutional freedoms. Because unless people start to self-regulate, the sense that we’re out of control is going to lead to genuine threats to our freedom. We’ve come a ways today, but we’ve got a long ways to go yet. I hope you’ll become the leaders in this, so we don’t have to worry about it anymore.

Senator Kohl: We have an awful lot of freedom in America. But there’s always that tendency to use the system down to the last inch to maximize profit. We can push it too far, and do great damage to our country. We all hope very much that you take a step back and consider our common responsibilities as citizens. Thank you.

(The full hearing is available for viewing in the C-SPAN archives.)

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Kohl was a noted proponent of commonsense gun control, especially among minors. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Konami’s Lethal Enforcers, a light-gun-based shooting-gallery game, was, like Mortal Kombat, one of the big arcade hits of 1992, and was likewise now coming home on consoles and computers. |

| ↑3 | The dream of streaming videogame content in the same way that one streams television programs was an old one already by this point, dating back at least to the beginning of the previous decade. Despite many bold predictions and more scattershot attempts at actual implementation, it’s never quite come to pass in the comprehensive way that seemed so well-nigh inevitable in 1993. |

| ↑4 | Sega had actually rolled out its own content-rating system just before the release of Mortal Kombat in September of 1993. Shortly thereafter, Sega and Nintendo, feeling the heat not only from Washington but from such powerful entities as California’s attorney general, did indeed agree to work together on a joint rating system — an unusual step for two companies whose relationship had heretofore been defined by their mutual loathing. On the very morning of this hearing, most of the rest of the video- and computer-game industry signed on to the initiative. |

| ↑5 | The body of psychological research on the subject was — and is — nowhere near as clear-cut as this formulation implies. And the industry was, of course, motivated to implement a voluntary rating system by fear of government action rather than a sudden conviction that its products could indeed be harmful to children. |

| ↑6 | Passed on November 30, 1993, the Brady Bill was a landmark piece of gun-control legislation which mandated that all prospective purchasers of a gun must first pass a background check and then wait five days to take delivery of their weapon. |

| ↑7 | The player’s objective in Night Trap, of course, is not to trap and kill women but rather to protect them from others who seek to do so. |

| ↑8 | This is, at best, an extremely dubious etymology. The Danish word “tøj,” which is pronounced like the English “toy,” actually means clothing. While “værktøjer” means tools, there is no single word for “little tools”: one would need to say “små værktøjer” to get that concept across. The Danish word for toy, on the other hand, is “legetøj.” If the English word descends from the Scandinavian languages at all, it is almost certainly an abbreviated version of this word. Even this, however, is by no means a firmly established etymology. |

| ↑9 | I have seen no evidence in my own research that there was ever a time when videogames were as popular among girls as boys. |

| ↑10 | This chip also allowed Nintendo to assure that they collected a royalty from each and every game that was sold for their console — something Atari wouldn’t or couldn’t do during the first videogame craze. |

| ↑11 | It wouldn’t have been technically feasible to release a Nintendo version of Night Trap because the company had no CD drive in its product catalog. |

| ↑12 | Rosenthal doesn’t make it clear here that, in keeping with the computer focus of the SPA, this list includes only games for computers, not consoles. Further, only games that were sold as boxed products in retail stores are included; the list misses entirely the vibrant shareware scene, where games like id’s Wolfenstein 3D were already pushing the envelope on gore and violence at least as much as Sega. Thus it provides a somewhat distorted view of the overall state of gaming even on computers. |