MicroProse had just published Master of Magic, the second grand-strategy game from the Austin, Texas-based studio SimTex, when SimCity 2000 made the world safe for numbered strategy sequels. After a quick palate cleanser in the form of a computerized version of the Avalon Hill board game 1830: Railroads & Robber Barons, Steve Barcia and the rest of the SimTex crew turned their attention to a sequel to Master of Orion, their 1993 space opera that was already widely revered as one of the finest ever examples of its breed.

Originally announced as a product for the Christmas of 1995, it took the sequel one full year longer than that to actually appear. And this was, it must be said, all for the better. Master of Magic had been a rather brilliant piece of game design whose commercial prospects had been all but destroyed by its premature release in a woefully buggy state. To their credit, SimTex patched it, patched it, and then patched it some more in the months that followed, until it had realized most of its immense potential as a game. But by then the damage had been done, and what might have been an era-defining strategy game like Civilization — or, indeed, the first Master of Orion — had been consigned to the status of a cult classic. On the bright side, MicroProse did at least learn a lesson from this debacle: Master of Orion II: Battle at Antares was given the time it needed to become its best self. The game that shipped just in time for the Christmas of 1996 was polished on a surface level, whilst being relatively well-balanced and mostly bug-free under the hood.

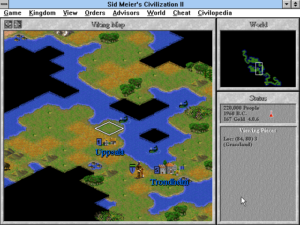

Gamers’ expectations had changed in some very significant ways in the three years since its predecessor’s release, and not generally to said predecessor’s benefit. The industry had now completed the transition from VGA graphics, usually running at a resolution of 320 X 200, to SVGA, with its resolutions of 640 X 480 or even more. The qualitative difference belies the quantitative one. Seen from the perspective of today, the jump to SVGA strikes me as the moment when game graphics stop looking undeniably old, when they can, in the best cases at any rate, look perfectly attractive and even contemporary. Unfortunately, Master of Orion I was caught on the wrong side of this dividing line; a 1993 game like it tended to look far uglier in 1996 than, say, a 1996 game would in 1999.

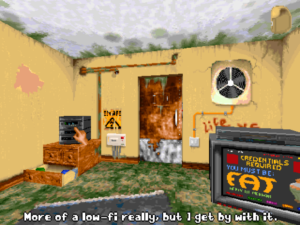

So, the first and most obvious upgrade in Master of Orion II was a thoroughgoing SVGA facelift. The contrast is truly night and day when you stand the two games up side by side; the older one looks painfully pixelated and blurry, the newer one crisp and sharp, so much so that it’s hard to believe that only three years separate them. But the differences at the interface level are more than just cosmetic. Master of Orion II‘s presentation also reflects the faster processor and larger memory of the typical 1996 computer, as well as an emerging belief in this post-Windows 95 era that the interface of even a complex strategy game aimed at the hardcore ought to be welcoming, intuitive, and to whatever extent possible self-explanatory. The one we see here is a little marvel, perfectly laid out, with everything in what one intuitively feels to be its right place, with a helpful explanation never any farther away than a right click on whatever you have a question about. It takes advantage of all of the types of manipulation that are possible with a mouse — in particular, it sports some of the cleverest use of drag-and-drop yet seen in a game to this point. In short, everything just works the way you think it ought to work, which is just about the finest compliment you can give to a user interface. Master of Orion I, for all that it did the best it could with the tools at its disposal in 1993, feels slow, jerky, and clumsy by comparison — not to mention ugly.

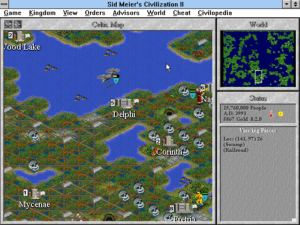

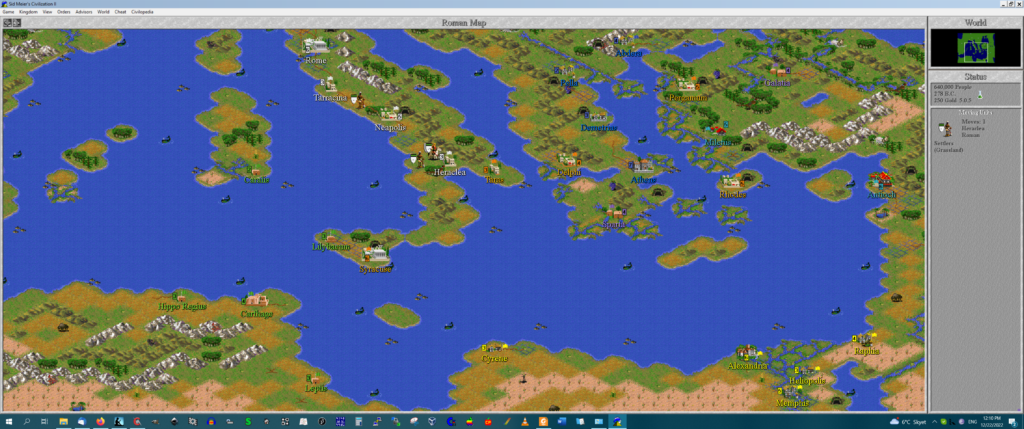

…and its equivalent in Master of Orion II. One of the many benefits of a higher resolution is that even the “Huge” galaxy I’ve chosen to play in here now fits onto a single screen.

If Master of Orion II had attempted to be nothing other than a more attractive, playable version of its antecedent, plenty of the original game’s fans would doubtless have welcomed it on that basis alone. In fact, one is initially tempted to believe that this is where its ambitions end. When we go to set up a new game, what we find is pretty much what we would imagine seeing in just such a workmanlike upgrade. Once again, we’re off to conquer a procedurally generated galaxy of whatever size we like, from Small to Huge, while anywhere from two to eight other alien races are attempting to do the same. Sure, there are a few more races to play as or against this time, a new option to play as a custom race with strengths and weaknesses of our own choosing, and a few other new wrinkles here and there, but nothing really astonishing. For example, we do have the option of playing against other real people over a network now, but that was becoming par for the course in this post-DOOM era, when just about every game was expected to offer some sort of networked multiplayer support, and could expect to be dinged by the critics if it didn’t. So, we feel ourselves to be in thoroughly familiar territory when the game proper begins, greeting us with that familiar field of stars, representing yet another galaxy waiting to be explored and conquered.

Master of Orion II‘s complete disconnection from the real world can be an advantage: it can stereotype like crazy when it comes to the different races, thereby making each of them very distinct and memorable. None of us have to feel guilty for hating the Darlocks for the gang of low-down, backstabbing, spying blackguards they are. If Civilization tried to paint its nationalities with such a broad brush, it would be… problematic.

But when we click on our home star, we get our first shock: we see that each star now has multiple planets instead of the single one we’re used to being presented with in the name of abstraction and simplicity. Then we realize that the simple slider bars governing each planetary colony’s output have been replaced by a much more elaborate management screen, where we decide what proportion of our population will work on food production (a commodity we never even had to worry about before), on industrial production, and on research. And we soon learn that now we have to construct each individual upgrade we wish our colony to take advantage of by slotting it into a build queue that owes more to Master of Magic — and by extension to that game’s strong influence Civilization — than it does to Master of Orion I.

By the middle and late game, your options for building stuff can begin to overwhelm; by now you’re managing dozens (or more) of individual colonies, each with its own screen like this. The game does offer an “auto-build” option, but it rarely makes smart choices; you can kiss your chances of winning goodbye if you use it on any but the easiest couple of difficulty levels. It would be wonderful if you could set up default build queues of your own and drag and drop them onto colonies, but the game’s interest in automation doesn’t extend this far.

This theme of superficial similarities obscuring much greater complexity will remain the dominant one. The mechanics of Master of Orion II are actually derived as much from Master of Magic and Civilization as from Master of Orion I. It is, that is to say, nowhere near such a straightforward extension of its forerunner as Civilization II is. It’s rather a whole new game, with whole new approaches in several places. Whereas the original Master of Orion was completely comfortable with high-level abstraction, the sequel’s natural instinct is to drill down into the details of everything it can. Does this make it better? Let’s table that question for just a moment, and look at some of the other ways in which the game has changed and stayed the same.

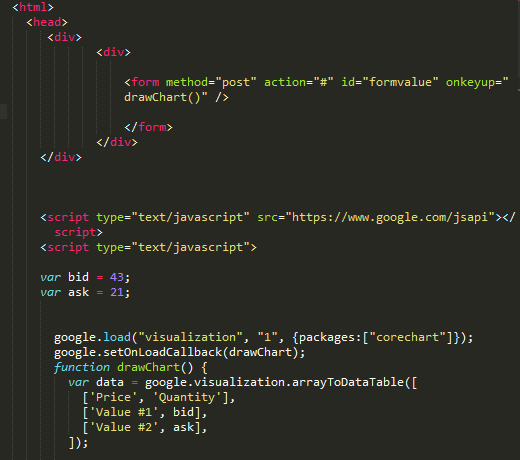

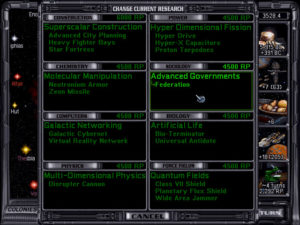

The old research system, which allowed you to make progress in six different fields at once by manipulating a set of proportional sliders, has been replaced by one where you can research just one technology at a time, like in Civilization. It’s one of the few places where the second game is less self-consciously “realistic” than the first; the scientific establishment of most real space-faring societies will presumably be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. But, in harking back so clearly to Civilization rather than to its own predecessor, it says much about where Steve Barcia’s head was at as he was putting this game together.

Master of Orion I injected some entropy into its systems by giving you the opportunity to research only a randomized subset of the full technology tree, forcing you to think on your feet and play the hand you were given. The sequel divides the full ladder of Progress into groupings of one to three technologies that are always the same, and lets you choose one of them from each group — and only one of them — for yourself rather than choosing for you. You still can’t research everything, in other words, but now it’s you who decides what does get researched. (This assumes that you aren’t playing a race with the “Creative” ability, which lets you gain access to all available technologies each step of the way, badly unbalancing the game in the process.)

The research screen in a game that’s pretty far along. We can choose to research in just one of the eight categories at a time, and must choose just one technology within that category. The others are lost to us, unless we can trade for or steal them from another race.

We’re on more familiar ground when it comes to our spaceships and all that involves them. Once again, we can design our own ships using all of the fancy technologies our scientists have recently invented, and once again we can command them ourselves in tactical battles that don’t depart all that much from what we saw in the first game. That said, even here there are some fresh complications. There’s a new “command point” system that makes the number of fleets we can field dependent on the communications infrastructure we’ve built in our empire, while now we also need to build “freighters” to move food from our bread-basket planets to those focused more on industry or research. Another new wrinkle here is the addition of “leaders,” individuals who come along to offer us their services from time to time. They’re the equivalent of Master of Magic‘s heroes, to the extent that they even level up CRPG-style over time, although they wind up being vastly less consequential and memorable than they were in that game.

Leaders for hire show up from time to time, but you never develop the bonds with them that you do with Master of Magic‘s heroes. That’s a pity; done differently, leaders might have added some emotional interest to a game that can feel a bit dry.

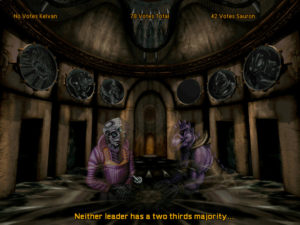

The last major facet of the game after colony, research, and ship management is your relationship with the other aliens you eventually encounter. Here again, we’re on fairly familiar ground, with trade treaties, declarations of war and peace and alliance, and spying for purposes of information theft or sabotage all being possible and, on the more advanced difficulty levels, necessary. We have three ways of winning the game, which is one more than in Master of Orion I. As before, we can simply exterminate all of the other empires, or we can win enough of them over through friendship or intimidation that they vote to make us the supreme leader of a Galactic Council. But we can now also travel to a different dimension and defeat a mysterious alien race called the Antarans that live there, whereupon all of the races back in our home dimension will recognize us as the superior beings we’ve just proved ourselves to be. Here there are more echoes of Master of Magic — specifically, of that game’s two planes of Arcanus and Myrror and the dimensional gates that link them together.

What to make of this motley blend, which I would call approximately 50 percent Master of Orion I, 25 percent Civilization, and 25 percent Master of Magic? First, let me tell you what most fans of grand strategy think. Then, I’ll give you my own contrarian take on it..

The verdict of the masses is clear: Master of Orion II is one of the most beloved and influential strategy games of all time. As popular in the latter 1990s as any grand-strategy game not called Civilization, it’s still widely played today — much more so, I would reckon, than the likes of its contemporary Civilization II. (Certainly Master of Orion II looks far less dated today by virtue of not running under Windows and using the Windows 3 widgets — to say nothing of those oh-so-1990s live-action video clips Civilization II featured.) It’s often described as the archetypal strategic space opera, the Platonic ideal which every new space-based grand-strategy game must either imitate or kick against (or a little of both). And why not? Having received several patches back in the day to correct the few issues in its first release, it’s finely balanced (that “Creative” ability aside — and even it has been made more expensive than it used to be), rich in content, and reasonably attractive to look at even today. And on top of all that there’s a gob-smackingly good interface that hardly seems dated at all. What’s not to like?

Well… a few things, in this humble writer’s opinion. For me, the acid test for additional complexity in a game is partially whether it leads to more “interesting choices,” as Sid Meier would put it, but even more whether it makes the fiction come more alive. (I am, after all, very much an experiential player, very much in tune with Meier’s description of the ideal game of Civilization as “an epic story.”) Without one or preferably both of these qualities, added complexity just leads to added tedium in my book. In the beginning, when I’m developing only one or two planets, I can make a solid case for Master of Orion II‘s hands-on approach to colony management using these criteria. But when one or two colonies become one or two dozen, then eventually one or two hundred, the negatives rather outweigh the positives for me. Any benefits you get out of dragging all those little colonists around manually live only at the margins, as it were. For the reality is that you’ll quickly come up with a standard, rote approach to building up each new planet, and see it through as thoughtlessly as you put your shirt on each morning. At most, you might have just a few default approaches, depending on whether you want the colony to focus on agriculture, industry, or research. Only in a rare crisis, or maybe in the rare case of a truly exceptional planet, will you mix it up all that much.

Master of Orion II strikes me as emblematic of a very specific era in strategy gaming, when advances in computing hardware weren’t redounding entirely to the benefit of game design. During the 1980s and early 1990s, designs were brutally constrained by slow processors and small memories; games like the first Master of Orion (as well as such earlier space operas as the 1983 SSG classic Reach for the Stars) were forced by their circumstance to boil things down to their essentials. By 1996, however, with processor speeds starting to be measured in the hundreds of megahertz and memory in the tens of megabytes, there was much more space for bells, whistles, and finicky knob-twiddling. We can see this in Civilization II, and we can see it even more in Master of Orion II. The problem, I want to say, was that computing technology had fallen into a sort of uncanny valley: the latest hardware could support a lot more mechanical, quantitative complexity, but wasn’t yet sufficient to implement more fundamental, qualitative changes, such as automation that allows the human player to intervene only where and when she will and improved artificial intelligence for the computer players. Tellingly, this last is the place where Master of Orion II has changed least. You still have the same tiny set of rudimentary diplomatic options, and the computer players remain as simple-minded and manipulable as ever. As with so many games of this era, the higher difficulty levels don’t make the computer players smarter; they only let them cheat more egregiously, giving them ever greater bonuses to all of the relevant numbers.

There are tantalizing hints that Steve Barcia had more revolutionary ambitions for Master of Orion II at one point in time. Alan Emrich, the Computer Gaming World scribe who coined the term “4X” (“Explore, Expand, Exploit, Exterminate”) for the first game and did so much to shape it as an early play-tester that a co-designer credit might not have been out of order, was still in touch with SimTex while they worked on the second. He states that Barcia originally “envisioned a ‘layered’ design approach so that people could focus on what they wanted to play. Unfortunately, that goal wasn’t reached.” Perhaps the team fell back on what was relatively easy to do when these ambitions proved too hard to realize, or perhaps at least part of the explanation lies in another event: fairly early in the game’s development, Barcia sold his studio to his publisher MicroProse, and accepted a more hands-off executive role at the parent company. From then on, the day-to-day design work on Master of Orion II largely fell to one Ken Burd, previously the lead programmer.

For whatever reason, Master of Orion II not only fails to advance the conceptual state of the art in grand strategy, but actually backpedals on some of the important innovations of its predecessor, which had already addressed some of the gameplay problems of the then-nascent 4X genre. I lament most of all the replacement of the first game’s unique approach to research with something much more typical of the genre. By giving you the possibility of researching only a limited subset of technologies, and not allowing you to dictate what that subset consists of, Master of Orion I forced you to improvise, to build your strategy around what your scientific establishment happened to be good at. (No beam-weapon technologies? Better learn to use missiles! Weak on spaceship-range-extending technologies to colonize faraway star systems? Better wring every last bit of potential out of those closer to home!) In doing so, it ensured that every single game you played was different. Master of Orion II, by contrast, strikes me as too amenable to rote, static strategizing that can be written up almost like an adventure-game walkthrough: set up your race like this, research this, this, and this, and then you have this, which will let you do this… every single time. Once you’ve come up with a set of standard operating procedures that works for you, you’ve done so forever. After that point, “it’s hard to lose Master of Orion II,” as the well-known game critic Tom Chick admitted in an otherwise glowing 2000 retrospective.

In the end, then, the sequel is a peculiar mix of craft and complacency. By no means can one call it just a re-skinning; it does depart significantly from its antecedent. And yet it does so in ways that actually make it stand out less rather than more from other grand-strategy games of its era, thanks to the anxiety of influence.

For influence, you see, can be a funny thing. Most creative pursuits should be and are a sort of dialog. Games especially have always built upon one another, with each worthy innovation — grandly conceptual or strictly granular, it really doesn’t matter — finding its way into other games that follow, quite possibly in a more evolved form; much of what I’ve written on this very site over the past decade and change constitutes an extended attempt to illustrate that process in action. Yet influence can prove a double-edged sword when it hardens into a stultifying conventional wisdom about how games ought to be. Back in 1973, the literary critic Harold Bloom coined the term “anxiety of influence” in reference to the gravitational pull that the great works of the past can exert on later writers, convincing them to cast aside their precious idiosyncrasies out of a perceived need to conform to the way things ought to be done in the world of letters. I would argue that Civilization‘s set of approaches have cast a similar pall over grand-strategy-game design. The first Master of Orion escaped its long shadow, having been well along already by the time Sid Meier’s own landmark game was released. But it’s just about the last grand-strategy game about which that can be said. Master of Orion II reverts to what had by 1996 become the mean: a predictable set of bits and bobs for the player to busy herself with, arranged in a comfortably predictable way.

When I think back to games of Master of Orion I, I remember the big events, the lightning invasions and deft diplomatic coups and unexpected discoveries. When I think back to games of Master of Orion II, I just picture a sea of data. When there are too many decisions, it’s hard to call any of them interesting. Then again, maybe it’s just me. I know that there are players who love complexity for its own sake, who see games as big, fascinating systems to tweak and fiddle with — the more complicated the better. My problem, if problem it be, is that I tend to see games as experiences — as stories.

Ah, well. Horses for courses. If you’re one of those who love Master of Orion II — and I’m sure that category includes many of you reading this — rest assured that there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. As for me, all this time spent with the sequel has only given me the itch to fire up the first one again…

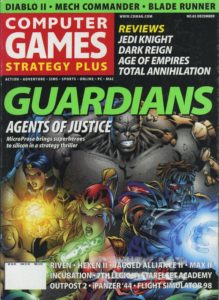

Although I’ve never seen any hard sales numbers, all indications are that Master of Orion II was about as commercially successful as a game this time-consuming, slow-paced, and cerebral — and not named Civilization — could possibly be, most likely selling well into the hundreds of thousands of units. Yet its success didn’t lead to an especially bright future for SimTex — or MicroProse Austin, as it had now become known. In fact, the studio never managed to finish another game after it. Its last years were consumed by an expensive boondoggle known as Guardians: Agents of Justice, another brainchild of Steve Barcia, an “X-COM in tights,” with superheroes and supervillains instead of soldiers and aliens. That sounds like a pretty fantastic idea to me. But sadly, a turn-based tactical-combat game was at odds with all of the prevailing trends in an industry increasingly dominated by first-person shooters and real-time strategy; one frustrated MicroProse executive complained loudly that Barcia’s game was “slow as a pig.” It was accordingly forced through redesign after redesign, without ever arriving at anything that both satisfied the real or perceived needs of the marketers and was still fun to play. At last, in mid-1998, MicroProse pulled the plug on the project, shutting down the entirety of its brief-lived Austin-based subsidiary at the same time. And so that was that for SimTex; Master of Orion III, when it came, would be the work of a completely different group of people.

Guardians: Agents of Justice was widely hyped over the years. MicroProse plugged it enthusiastically at each of the first four E3 trade shows, and a preview was the cover story of Computer Games Strategy Plus‘s December 1997 issue. “At least Agents never graced a CGW cover,” joshed Terry Coleman of the rival Computer Gaming World just after Guardians‘s definitive cancellation.

Steve Barcia never took up the design reins of another game after conceiving Guardians of Justice, focusing instead on his new career in management, which took him to the very different milieu of the Nintendo-exclusive action-games house Retro Studios after his tenure at MicroProse ended. Some might consider this an odd, perchance even vaguely tragic fate for the designer of three of the most respected and beloved grand-strategy games of all time. On the other hand, maybe he’d just said all he had to say in game design, and saw no need to risk tarnishing his stellar reputation. Either way, his creative legacy is more than secure.

(Sources: the book The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry by Harold Bloom; Computer Gaming World of October 1995, December 1996, March 1997, June 1997, July 1997, and October 1998; Computer Games Strategy Plus of December 1997. Online sources include Alan Emrich’s retrospective on the old Master of Orion III site and Tom Chick’s piece on Master of Orion II for IGN.

Master of Orion I and II are available as a package from GOG.com. So, you can compare and contrast, and decide for yourself whether I’m justified in favoring the original.)