The Voyage of Magellan, Chapter 26: Homeward Bound

The CRPG Renaissance, Part 5: Fallout 2 and Baldur’s Gate

As we learned in the earlier articles in this series, Interplay celebrated the Christmas of 1997 with two new CRPGs. One of them, the striking post-apocalyptic exercise called Fallout, was greeted with largely rave reviews. The other, of course, was the far less well-received licensed Dungeons & Dragons game called Descent to Undermountain. The company intended to repeat the pattern in 1998, with another Fallout and another Dungeons & Dragons game. This time, however, the public’s reception of the two efforts would be nearly the polar opposite of last time.

It’s perhaps indicative of the muddled nature of the project that Interplay couldn’t come up with any plot-relevant subtitle for Fallout 2. It’s just another “Post-Nuclear Role-Playing Game.”

Tim Cain claims that he never gave much of a thought to any sequels to Fallout during the three and a half years he spent working on the first game. Brian Fargo, on the other hand, started to think “franchise” as soon as he woke up to Fallout’s commercial potential circa the summer of 1997. Fallout 2 was added to Interplay’s list of active projects a couple of months before the original game even shipped.

Interplay’s sorry shape as a business made the idea of a quick sequel even more appealing than it might otherwise have been. For it should be possible to do it relatively cheaply; the engine and the core rules were already built. It would just be a matter of generating a new story and design, ones that would reuse as many audiovisual assets as possible.

Yet Fargo was not pleased by the initial design proposals that reached his desk. So, just days after Fallout 1 had shipped, he asked Tim Cain to get together with his principal partners Leonard Boyarsky and Jason Anderson and come up with a proposal of their own for the sequel. The three were dismayed by this request; exhausted as they were by months of crunch on Fallout 1, they had anticipated enjoying a relaxing holiday season, not jumping right back into the fray on Fallout 2. Their proposal reflected their mental exhaustion. It spring-boarded off of a joking aside in the original game’s manual, a satirical advertisement which Jason Anderson had drawn up in an afternoon when he was told by Interplay’s printer that there would be an unsightly blank page in the booklet as matters currently stood. The result was the “Garden of Eden Creation Kit”: “When all clear sounds on your radio, you don’t want to be caught without one!” Elaborating on this thin shred of a premise, the sequel would cast you as a descendant of the star of the first game, sent out into the dangerous wastelands to recover one of these Garden of Eden Kits in lieu of a water chip. This apple did not fall far from the tree.

But as it turned out, that suited Brian Fargo just fine. Within a month of Fallout 1′s release, Cain, Boyarsky, and Anderson had been officially assigned to the Fallout 2 project. None of them was terribly happy about it; what all three of them really wanted were a break, a bonus check, and the chance to work on something else, roughly in that order of priority. In January of 1998, feeling under-appreciated and physically incapable of withstanding the solid ten months of crunch that he knew lay before him, Cain turned in his resignation. Boyarsky and Anderson quit the same day in a show of solidarity. (The three would go on to found Troika Studios, whose games we will be meeting in future articles on this site, God willing and the creek don’t rise.)

Following their exodus, Fallout 2 fell to Feargus Urquhart and the rest of his new Black Isle CRPG division to turn into a finished product. Actually, to use the word “division” is to badly overstate Black Isle’s degree of separation from the rest of Interplay. Black Isle was more a marketing label and a polite fiction than a lived reality; the boundaries between it and the mother ship were, shall we say, rather porous. Employees tended to drift back and forth across the border without anyone much noticing.

This was certainly the case for most of those who worked on Fallout 2, a group which came to encompass about a third of the company at one time or another. Returning to the development approach that had yielded Wasteland a decade earlier, Fargo and Urquhart parceled the game out to whoever they thought might have the time to contribute a piece of it. Designer and writer Chris Avellone, who was drafted onto the Fallout 2 team for a few months while he was supposed to be working on another forthcoming CRPG called Planescape: Torment, has little positive to say about the experience: “I do feel like the heart of the team had gone. And all that was left were a bunch of developers working on different aspects of the game like a big patchwork beast. But there wasn’t a good spine or heart to the game. We were just making content as fast as we could. Fallout 2 was a slapdash product without a lot of oversight.”

Still, the programmers did fix some of what annoyed me about Fallout 1, by cleaning up some of the countless little niggles in the interface. Companions were reworked, such that they now behave more or less as you’d expect: they’re no longer so likely to shoot you in the back, are happy to trade items with you, and don’t force you to kill them just to get around them in narrow spaces. Although the game as a whole still strikes me as more clunky and cumbersome than it needs to be — the turn-based combat system is as molasses-slow as ever — the developers clearly did make an effort to unkink as many bottlenecks as they could in the time they had.

But sadly, Fallout 2 is a case of one step forward, one step back: although it’s a modestly smoother-playing game, it lacks its predecessor’s thematic clarity and unified aesthetic vision. Its world is one of disparate parts, slapped together with no rhyme, reason, or editorial oversight. It wants to be funny — always the last resort of a game that lacks the courage of its fictional convictions — but it doesn’t have any surfeit of true wit to hand. It tries to make up for the deficit the same way as many a game of this era, by transgressing boundaries of taste and throwing out lazy references to other pop culture as a substitute for making up its own jokes. This game is very nerdy male, very adolescent-to-twenty-something, and very late 1990s — so much so that anyone who didn’t live through that period as part of the same clique will have trouble figuring out what it’s on about much of the time. I do understand most of the spaghetti it throws at the walls — lucky me! — but that doesn’t keep me from finding it fairly insufferable.

Fallout 2 shipped in October of 1998, just when it was supposed to. But its reception in the gaming press was noticeably more muted than that of its predecessor. Reviewers found it hard to overlook the bugs and glitches that were everywhere, the inevitable result of its rushed and chaotic development cycle, even as the more discerning among them made note of the jarring change in tone and the lack of overall cohesion to the story and design. The game under-performed expectations commercially as well, spending only one week in the American top ten. In the aftermath, Brian Fargo’s would-be CRPG franchise looked like it had already run its course; no serious plans for a Fallout 3 would be mooted at Interplay for quite some time to come.

Yet Fallout 2 did do Interplay’s other big CRPG for that Christmas an ironic service. When BioWare told Fargo that they would like a couple of extra months to finish Baldur’s Gate up properly, the prospect of another Interplay CRPG on store shelves that October made it easier for him to grant their request. So, instead of taking full advantage of the Christmas buying season, Baldur’s Gate didn’t finally ship until a scant four days before the holiday. Never mind: the decision not to ship it before its time paid dividends that some quantity of ephemeral Christmas sales could never have matched. Plenty of gamers proved ready to hand over their holiday cash and gift cards in the days right after Christmas for the most hotly anticipated Dungeons & Dragons computer game since Pool of Radiance. Baldur’s Gate sold 175,000 units before 1998 was over. (Just to put that figure in perspective, this was more copies than Fallout 1 had sold in fifteen months.) Its sales figures would go on to top 1 million units in less than a year, making it the bestselling CRPG to date that wasn’t named Diablo. The cover provided by Fallout 2 helped to ensure that Dr. Muzyka and Dr. Zeschuk would never have to see another patient again.

I’m not someone who places a great deal of sentimental value on physical things. But despite my lack of pack-rattery, some bits of flotsam from my early years have managed to follow me through countless changes of address on both sides of a very big ocean. Playing Baldur’s Gate prompted me to rummage around in the storage room until I came up with one of them. It goes by the name of In Search of Adventure. This rather generically titled little book is, as it says on the front cover, a “campaign adventure” for tabletop Dungeons & Dragons. Note the absence of the “Advanced” prefix; this adventure is for the non-advanced version of the game, the one that was sold in those iconic red and blue boxes that conquered the cafeteria lunch tables of Middle America during the first few years of the 1980s, when TSR dared to dream that their flagship game might become the next Monopoly. If we’re being honest, I always preferred to play this version of the game even after its heyday passed away. It seemed to me more easy-going, more fun-focused, less stuffily, pedantically Gygaxian.

Anyway, the campaign adventure in question came out in 1987, well after my preferred version of Dungeons & Dragons had become the weak sister to its advanced, hardcore sibling — unsurprisingly so, given that pretty much the only people still playing the game by that point were hardcore by definition.

In Search of Adventure is actually a compilation of nine earlier adventure modules that TSR published for beginning-level characters, crammed together into one book with a new stub of a plot to serve as a connecting tissue. I dug it out of storage and have proceeded to talk about it here because it reminds me inordinately of Baldur’s Gate, which works on exactly the same set of principles. There’s an overarching story to it, sure, but it too is mostly just a big grab bag of geography to explore and monsters to fight, in whatever order you prefer. In this sense and many others, it’s defiantly traditionalist. It has more to do with Dungeons & Dragons as it was played around those aforementioned school lunch tables than it does with the avant-garde posturings of TSR’s latter days. As I noted in my last article, the Forgotten Realms in which Baldur’s Gate is set — and in which In Search of Adventure might as well be set, for all that it matters — is so appealing to players precisely because it’s so uninterested in challenging them. The Forgotten Realms is the archetypal place to play Dungeons & Dragons. Likewise, Baldur’s Gate is an archetypal Dungeons & Dragons computer game, the essence of the “a group of adventurers meet in a bar…” school of role-playing. (You really do meet some of your most important companions in Baldur’s Gate in a bar…)

Luke Kristjanson, the BioWare writer responsible for most of the dialog in Baldur’s Gate, says that he never saw the computer game as “a simulation of a fully-realized Medieval world”: “It was a simulation of playing [tabletop] Dungeons & Dragons.” This statement is, I think, the key to understanding where BioWare was coming from and what still makes their game so appealing today, more than a quarter-century on.

Opening with a Nietzsche quote leads one to fear that Baldur’s Gate is going to try to punch way, way above its weight. Thankfully, it gets the pretentiousness out of its system early and settles down to meat-and-potatoes fare. BioWare’s intention was never, says Luke Kristjanson, to make “a serious fantasy for serious people.” Thank God for that!

But here’s the brilliant twist: in order to conjure up the spirit of those cafeteria gatherings of yore, Baldur’s Gate uses every affordance of late-1990s computer technology that it can lay its hands on. It wants to give you that 1980s vibe, but it wants to do it better — more painlessly, more intuitively, more prettily — than any computer of that decade could possibly have managed. Call it neoclassical digital Dungeons & Dragons.

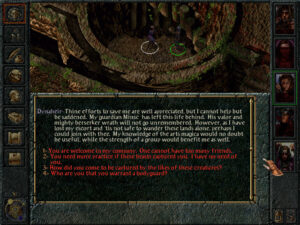

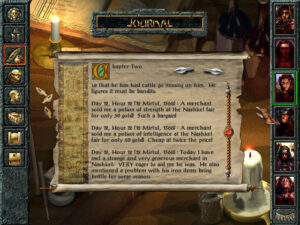

The game begins in a walled cloister known as Candlekeep, which has a bit of a Name of the Rose vibe, being full of monks who have dedicated their lives to gathering and preserving the world’s knowledge. The character you play is an orphan who has grown up in Candlekeep as the ward of a kindly mage named Gorion. This bucolic opening act gives you the opportunity to learn the ropes, via a tutorial and a few simple, low-stakes quests. But soon enough, a fearsome figure in armor shatters the peace of the cloister, killing Gorion and forcing you to take to the road in search of adventure (to coin a phrase). The game does suggest at the outset that you visit a certain tavern where you might find some useful companions, but it never insists that you do this or anything else. Instead you’re allowed to go wherever you want and to do exactly that thing which pleases you most once you get there. When you do achieve milestones in the main plot, whether deliberately or inadvertently, they’re heralded with onscreen chapter breaks which demonstrate that the story is progressing, because of or despite your antics. In this way, the game tries to create a balance between player freedom and the equally bracing sense of being caught up in an epic plot, one in which you will come to play the pivotal role — being, as you eventually learn, the “Chosen One” who has been marked by destiny. Have I mentioned that Baldur’s Gate is not a game that shirks from fantasy clichés?

Of course, there’s an unavoidable tension between the set-piece plot of the chapter-based structure and the open-world aspect of the game — a tension which we’ve encountered in other games I’ve written about. The main plot is constantly urging you forward, insisting that the fate of the world is at stake and time is of the essence. Meanwhile the many side quests are asking you to rescue a lost housecat or collect wolf pelts for a merchant. If you take the game at its word and rush forward with a sense of urgency, you’ll not only come to the climax under-leveled but will have missed most of the fun. All of which is to say that Baldur’s Gate is best approached like that In Search of Adventure module: just start walking around. Go see what is to be found in those parts of your map that are still blank. Sooner or later, you’ll trigger the next chunk of the main plot anyway.

It’s amazing how enduring some of what is to be found in those blank spaces has proved. My wife likes to read graphic novels. I was surprised recently to see that she’d started on a Dungeons & Dragons-branded one called Days of Endless Adventure, with a copyright date of 2021. I was even more surprised when I flipped it open idly and came face to face with the simple-minded ranger Minsc and his precious pet hamster Boo, both of whom were introduced to the world in Baldur’s Gate.

A congenital visual blurriness dogs this game, the result of a little bit too much detail being crammed into a relatively low resolution of 640 X 480, combined with a subdued, brown- and gray-heavy color palette. My middle-aged eyes weren’t always so happy about it, especially when I played on a television in the living room.

As it happened, I had had quite a time with Minsc when I played the game. He joined my party fairly early on, on the condition that we would try to rescue his friend, a magic user named Dynaheir who was being imprisoned in a gnoll stronghold. Unfortunately, I applied the same logic to his principal desire that I did to the main quest line; I’d get to it when I got to it. I maintained this attitude even as he nagged me about it with increasing urgency. One day the dude just flipped out on me, went nuts and started to attack me and my other companions. What’s a person to do in such a situation? Reader, I killed him and his pet hamster.

I was playing a ranger myself, so I didn’t think losing his services would be any big problem. I didn’t notice until days later that killing him — even though, I rush to stipulate again, he attacked me first — had turned me into a “fallen ranger.” I’m told by people who know about such things that this is far from ideal, because it means that you’ve essentially been reduced to the status of a vanilla fighter, albeit one who craves a lot more experience points than usual to advance a level. Oh, well. I didn’t feel like going back so many hours, and I was in more of a “roll with the punches” than a “try and try again” frame of mind anyway. (I’m also told that there will be a way to reverse my fallen condition when I get around to playing Baldur’s Gate II with the same party. So that’s something to look forward to, I guess.) By way of completing the black comedy, I later did rescue Dynaheir and took her into my party. But I was careful not to mention that I had ever met her mysteriously vanished friend…

Any given play-through of Baldur’s Gate is guaranteed to generate dozens of such anecdotes, which combine to make its story your story, even if the text of the chapter breaks is the same for everyone. You don’t have to walk on eggshells, afraid that you’re going to break some necessary piece of plot machinery. Again, it’s you who gets to choose where you go, what you do there, and who travels with you on your quest. Any mistake you make along the way that doesn’t get you and all your friends killed can generally be recovered from or at least lived with, as I did my fallen-ranger status. Tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, says Luke Kristjanson, is about “[being with] your friends [and] doing something fun. And occasionally one’s a jackass and does something weird and you roll with it.” It does seem to me that rolling with it is the only good way to play this second-order simulation of that social experience.

The first companion to join you will probably be Imoen, a spunky female thief. The personalities of your companions are all firmly archetypal, but most of them are likeable enough that it’s hard to complain. Sometimes fantasy comfort food goes down just fine.

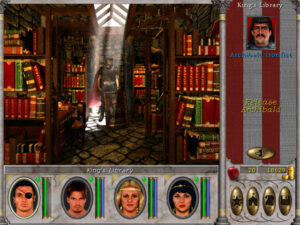

Baldur’s Gate’s specific methods of presenting its world of freedom and opportunity have proved as influential as the design philosophies that undergird it. The Infinity Engine provided the presentational blueprint for a whole school of CRPGs that are still with us to this day. You look down on the environment and the characters in it from a free-scrolling isometric point of view. You can move the “camera” anywhere you like in the current area, independent of the locations of your characters. That said, a fog-of-war is implemented: places your characters have not yet seen are completely blacked out, and you can’t know what other people or monsters are getting up to if they’re out of your characters’ line of sight.

The interface proper surrounds this view on three sides. Portraits of the members of your party — up to five of them, in addition to the character you create and embody from the outset — run down the right side of the screen. Command icons — some pertaining to the individual party members and some to the group as a whole or to the computer on which you’re running the game — stretch across the left side and bottom of the screen. An area just above the bottom line of icons can expand to display text, of which there is an awful lot in this game, mostly in the form of menu-driven conversations. (In 1998, we were still far from the era when it would be practical and cost-effective to have full voice-acting in a game with this much yammering. Instead just the occasional line of dialog is voiced, to establish personalities and set tones.) The interface is perhaps a bit more obscure and initially daunting than it might be in a modern game, but the contrast with the old keyboard-driven SSI Gold Box games could hardly be more stark. And thankfully, unlike Fallout’s, Baldur’s Gate’s interface doesn’t make the mistake of prioritizing aesthetics over utility.

In short, Baldur’s Gate tries really, really hard to be approachable in the way that modern players have come to expect, even if it doesn’t always make it all the way there. Take, for instance, its journal, an exhaustive chronicle of the personal story that you are generating as you play. That’s great. But what’s less great is that it can be inordinately difficult to sift through the huge mass of text to find the details of a quest you’re pretty sure you accepted sometime last week. Most of us would love to have a simple bullet list of quests to go along with the verbose diary, however much that may cause the hardcore immersion-seekers to howl in protest at the gameyness of it all. Later Infinity Engine games corrected oversights like this one.

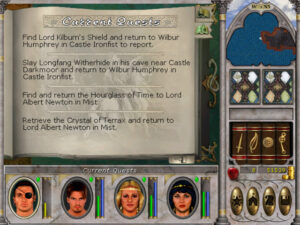

The most oft-discussed and controversial aspect of the Infinity Engine, back in the day and to some extent even today, is its implementation of combat. As we’ve learned, makers of CRPGs in the late 1990s faced a real conundrum when it came to combat. They wanted to preserve a measure of tactical complexity, but they also had to reckon with the reality of a marketplace that showed a clear preference for fast-paced, fluid gameplay over turn-based models. Fallout tried to square that circle by running in real-time until a fight began, at which point it forced you back into a turn-based framework; Might and Magic VI did a little better in my opinion by letting you decide when you wanted to go turn-based. In a way, BioWare was even more constrained than the designers of either of those two games, because they were explicitly making a digital implementation of a turn-based set of tabletop rules.

Their solution to the conundrum was real-time-with-pause, in which the computer automatically acts out the combat, adhering to the rules of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons but, critically, without advertising the breaks between rounds and turns. The player can assert her will at any point in the proceedings by tapping the space bar to pause the action, issuing new commands to her charges, and then tapping it again to let the battle resume.

Clever though the scheme is, not everyone loves it. And, to be sure, there are valid complaints to levy against it. Big fights can all too quickly degenerate into a blob of intersecting sprites, with spells going off everywhere and everyone screaming at once; it’s like watching twenty Tasmanian Devils — the Looney Tunes version, that is — in a fur-flying free-for-all. Yet there are ways to alleviate the confusion by making judicious use of the option to “auto-pause,” a hugely important capability that is mentioned only in oblique passing in the game’s 160-page manual, presumably because that document was sent to the printing press before the software it described had been finalized. Auto-pause will let you stop the action automatically whenever certain conditions of your choice are met — or even at the end of every single action taken by every single member of your party, if you choose to go that far. Doing so lets you effectively turn Baldur’s Gate into a purely turn-based game, if that’s your preference. Or you can go fully turn-based only for the really big fights that you know will require careful micro-management. This is what I do. The rest of the time, I just use a few judicious break points — a character is critically wounded, a spell caster has finished casting a spell, etc. — and otherwise rely on the good old space bar.

Another option — the best one for those most determined to turn the game into a simulation of playing tabletop Dungeons & Dragons with your mates — is to turn on artificial intelligence for every member of your party but the one you created. Then you just let them all do their things while you do yours. You may find yourself less enamored with this approach, however, after you become part of the collateral damage of one of Dynaheir’s Fireball spells for the first time. (Shades of the stone-stupid and deadly companions in Fallout…)

Baldur’s Gate’s combat definitely isn’t perfect, but in its day it was a good-faith attempt to deliver an experience that was recognizably Dungeons & Dragons while also catering to the demands of the contemporary marketplace. I think it holds up okay today, especially when placed in the context of the rest of the game that houses it, which has ambitions for its world and its fiction that transcend the tactical-combat simulations that the latter-day Gold Box games especially lapsed into. It is true that your companions’ artificial intelligence could be better, as it is true that it’s sometimes harder than it ought to be to figure out what’s really going on, a byproduct of graphics that are somewhat muddy even at the best of times and of having way too many character sprites in way too small a space. But your fighters, who don’t usually require too much micro-management, are the most affected by this latter problem, while your spell casters ought to be standing well back from the fray anyway, if they know what’s good for them. Another not-terrible approach, then, is to control your spell casters yourself, since they’re the ones who can most easily ruin their companions’ day, and leave your fighters to their own devices. But you’ll doubtless figure out what works best for you within the first few hours.

Indeed, Baldur’s Gate feels disarmingly modern in the way that it bends over backward to adjust itself to your preferred style of play. This encompasses not only the myriad of auto-pause and artificial-intelligence options but an adjustable global difficulty slider for combat. All of this allows you to breeze through the fights with minimal effort or hunker down for a long series of intricate tactical struggles, just as you choose. Giving your player as many ways to play as possible is seldom a bad choice in commercial game design. Not everyone had yet figured that out in the late 1990s.

If you want the ultimate simulation of playing tabletop Dungeons & Dragons with your friends, you can turn on an option to watch the actual die rolls scrolling past during combat.

BioWare and Interplay released an expansion pack to Baldur’s Gate called Tales of the Sword Coast just six months after the base game. Rather than serving as a sequel to the main plot, it’s content merely to add some new ancillary areas to explore betwixt and between fulfilling your destiny as The Chosen One. Given that I definitely don’t consider the main plot the most interesting part of Baldur’s Gate, I have no problem with this approach in theory. Nevertheless, the expansion pack strikes me as underwhelming and kind of superfluous — like a collection of all the leftover bits that failed to make the cut the first time around, which I suspect is exactly what it is. The biggest addition is an elaborate dungeon known as Durlag’s Tower, created to partially address one of the principal ironies of the base game: the fact that it contains surprisingly little in the way of dungeons and no dragons whatsoever. The latter failing would have to wait for the proper sequel to be corrected, but BioWare did try to shore up the former aspect by presenting an old-school, tactically complex dungeon crawl of the sort that Gary Gygax would have loved, a maze rife not only with tough monsters but with secret doors, illusions, traps, and all manner of other subtle trickery. Personally, I tend to find this sort of thing more tedious than exciting at this stage of my life, at least when it’s implemented in this particular game engine. I decided pretty quickly after venturing inside to let old Durlag keep his tower, since he seemed to be having a much better time there than I was.

Durlag’s Tower. The Infinity Engine doesn’t do so well in such narrow, trap-filled spaces. It’s hard to keep your characters from blundering into places that they shouldn’t.

While your reaction to the über-dungeon may be a matter of taste, a more objective ground for concern is all of the new sources of experience points the expansion adds, whilst raising the experience and level caps on your characters only modestly. As a result, it becomes that much easier to max out your characters before you finish the game, a state of affairs which is no fun at all. In my eyes, then, Baldur’s Gate is a better, tighter game without the expansion. For better or for worse, though, Tales of the Sword Coast has become impossible to extricate from the base game, being automatically incorporated into all of the modern downloadable editions. So, I’ll content myself with telling you to feel free to skip Durlag’s Tower and/or any of the other additional content if it’s not your thing. There’s nothing essential to the rest of the game to be found there.

Whatever its infelicities and niggles, it’s almost impossible to overstate the importance and influence of Baldur’s Gate in the broader context of gaming history. Forget the comparisons I’ve been making again and again in these articles to Pool of Radiance: one can actually make a case for Baldur’s Gate as the most important single-player CRPG released between 1981, the landmark year of the first Wizardry and Ultima, and the date of this very article that you’re reading.

Baldur’s Gate’s unprecedented level of commercial success transformed the intersection between tabletop Dungeons & Dragons and its digital incarnations from a one-way avenue into a two-way street; all of the future editions of the tabletop rules that would emerge under Wizards of the Coast’s watch would be explicitly crafted with an eye to what worked on the computer as well. At the same time, Baldur’s Gate cemented one of the more enduring abstract design templates in digital gaming history; witness the extraordinary success of 2023’s belated Baldur’s Gate 3. The CRPGs that more immediately followed Baldur’s Gate I, both those that were powered by the Infinity Engine and those that only borrowed some of its ideas, found ways to improve on the template in countless granular details, but they were all equally the heirs to this very first Infinity Engine game. Yes, Fallout got there first, and in some respects did it even better, with a less clichéd, more striking setting and an even deeper-seated commitment to acknowledging and responding to its player’s choices. And there’s more than a little something to be said for the role played by the goofy, janky, uninhibited Monty Haul fun of Might and Magic VI in the rehabilitation of the CRPG genre as well. Yet the fact remains that it was Baldur’s Gate that truly led the big, meaty CRPG out of the wilderness and back into the mainstream.

Then again, gaming history is not a zero-sum game. The note on which I’d prefer to end this series of articles is simply that the CRPG genre was back by 1999. Increasingly, it would be the computer games that drove sales of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons rather than the other way around. Meanwhile a whole lot of other CRPGs, including some of the most interesting ones of all, would be given permission to blaze their own trails without benefit of a license. I look forward to visiting or revisiting some of them with you in the years to come, as we explore this genre’s second golden age.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: For Baldur’s Gate, see my last article, with the addition of the book BioWare: Stories and Secrets from 25 Years of Game Development, which commenter Infinitron was kind enough to tell me about.

For Fallout 2: the book Beneath a Starless Sky: Pillars of Eternity and the Infinity Engine Era of RPGs by David L. Craddock. Computer Gaming World of February 1999; Retro Gamer 72 and 188. Also Chris Avellone’s appearance on Soren Johnson’s Designer Notes podcast and Tim Cain’s YouTube channel.

Where to Get Them: Fallout 2 and Baldur’s Gate are both available as digital purchases at GOG.com, the latter in an “enhanced edition” that sports some welcome quality-of-life improvements alongside some additional characters and quests that don’t sit as well with everyone. Note that it buying it does give you access to the original game as well.

The CRPG Renaissance, Part 4: …Long Live Dungeons & Dragons!

In December of 1997, Interplay Entertainment released Descent to Undermountain, the latest licensed Dungeons & Dragons computer game. It’s remembered today, to whatever extent it’s remembered at all, as one of the more infamous turkeys of an era with more than its share of over-hyped and half-baked creations, a fiasco almost on par with Battlecruiser 3000AD or Daikatana. The game was predicated on the dodgy premise that Dungeons & Dragons would make a good fit with the engine from Descent, Interplay’s last world-beating hit — and also a hit that was, rather distressingly for Brian Fargo and his colleagues, more than two years in the past by this point.

Simply put, Undermountain was a mess, the kind of career-killing disaster that no self-respecting game developer wants on his CV. The graphics, which had been crudely up-scaled from the absurdly low resolution of 320 X 240 to a slightly more respectable 640 X 480 at the last minute, still didn’t look notably better than those of the five-year-old Ultima Underworld. The physics were weirdly floaty and disembodied, perhaps because the engine had been designed without any innate notion of gravity; rats could occasionally fly, while the corpses of bats continued to hover in midair long after shaking off their mortal coil. In design terms as well, Undermountain was trite and rote, just another dungeon crawl in the decade-old tradition of Dungeon Master, albeit not executed nearly so well as that venerable classic.

Computer Gaming World, hot on the heels of giving a demo of Undermountain a splashy, breathless write-up (“This game looks like a winner…”), couldn’t even muster up the heart to print a proper review of the underwhelming finished product. The six-sentence blurb the magazine did deign to publish said little more than that “the search for a good Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game continues, because Descent to Undermountain is certainly not it.” The website GameSpot was less inclined to pull its punches: after running through a damning litany of the game’s problems, it told its readers bluntly that “if you buy Descent to Undermountain after reading this, you get what you deserve.” The critical consensus has not changed over the decades since. On the clearinghouse site MobyGames, Undermountain ranks today as the thirteenth worst digital RPG ever released, out of 9085 candidates in all. Back in 1997, reviewers and gamers alike marveled that Interplay, the same company that had released the groundbreaking and aesthetically striking Fallout just weeks earlier, could follow it up so quickly with something so awful.

In its way, then, Descent to Undermountain‘s name was accidentally appropriate. For it represented the absolute nadir of Dungeons & Dragons on computers, the depth of ignominy to which all of the cookie-cutter products from SSI and others had been inexorably descending over the last five years.

Then again, as a wise person once said, there does come a point where there’s nowhere left to go but up. Less than one year after Undermountain was so roundly scorned wherever it wasn’t ignored, another Dungeons & Dragons CRPG was released amidst an atmosphere of excitement and expectation that put even the reception of Pool of Radiance to shame. Almost as surprisingly, it too bore on its box the name of Interplay, a publisher whose highs and lows in the CRPG genre were equally without parallel. So, our goal for today is to understand how Interplay went from Descent to Undermountain to Baldur’s Gate. It’s an unlikely tale in the extreme, not least in the place and manner in which it begins.

Edmonton, Alberta, is no one’s idea of a high-tech incubator. “The Gateway to the North,” as the city styles itself, was built on oil and farming. These two things have remained core to its identity, alongside its beloved Edmonton Oilers hockey team and its somewhat less beloved but stoically tolerated sub-zero winter temperatures. The frontier ethic has never entirely left Edmonton; it has more in common with Billings, Montana, than it does with coastal Canadian cities like Montreal and Vancouver.

Into this milieu, insert three young men who were neither roughnecks nor farmers. Ray Muzyka, Greg Zeschuk, and Augustine Yip didn’t know one another when they were growing up in different quarters of Edmonton in the 1980s, but they were already possessed of some noteworthy similarities. Although all three had computers in their homes and enjoyed experimenting with the machines and the games they could play from an early age — Muzyka has recorded his first two games ever as Pirate Adventure and Wizardry on the Apple II — they directed their main energies toward getting into medical school and becoming doctors. “We never conceived of the possibility that you could have a career in videogames,” says Zeschuk. “You know, we’re from Edmonton, Canada. There were no companies that did that. There were some in Vancouver, but they were just starting out, like the Distinctive Software guys who would join Electronic Arts.”

The three men finally met in medical school — more specifically, at the University of Alberta during the late 1980s. Even here, though, they didn’t become fast friends right away. Only gradually did they come to realize that they had a set of shared interests that were anything but commonplace among their classmates: all three continued to play computer games avidly whenever the pressure of their studies allowed it. Witnessing the rapid evolution of personal computers, each began to ask himself whether he might be able to combine medicine with the technology in some satisfying and potentially profitable way. Then they began to have these conversations with each other. It seemed to them that there were huge opportunities in software for educating doctors. Already in 1990, a couple of years before they graduated from medical school, they started looking for technology projects as moonlighting gigs.

They kept at it after they graduated and became family practitioners. The projects got more complex, and they hired contractors to help them out. Their two most ambitious software creations were an “Acid-Base Simulator,” which they finished in 1994, and a “Gastroenterology Patient Simulator,” which they finished the following year. As their titles will attest, these products were a long, long way from a mainstream computer game, but the good doctors would cover the intervening distance with astonishing speed.

Wanting to set themselves on a firmer professional footing in software, Muzyka, Zeschuk, and Yip founded a proper corporation on February 1, 1995. They called it BioWare, a name that reflected a certain amount of bets-hedging. On the one hand, “BioWare” sounded fine as a name for a maker of medical software like the gastroenterology simulator they were still finishing up. On the other, they thought it was just catchy and all-purpose enough to let them branch out into other sorts of products, if doing so should prove feasible. In particular, they had become very interested in testing the waters of mainstream game development. “I liked medicine a lot,” says Muzyka. “I really liked it. I’m glad I was able to help people’s lives for the years that I did practice. I did a lot of emergency medicine in under-served areas in rural Alberta. It was really hard work, but really fun, really engaging, really exciting. [But] I love videogames.”

Their medical degrees were a safety net of a sort that most first-time entrepreneurs could only wish they had; they knew they could always go back to doctoring full-time if BioWare didn’t work out. “We maxed out our debt and our credit cards,” Muzyka says. “We just kind of went for it. It was like, whatever it took, this is what we’re doing. It never occurred to us [that] there would be risk in that. For me, it was a fun hobby at that point.”

Yet some differences soon became apparent between Muzyka and Zeschuk and their third partner Augustine Yip. Although the first two were willing and able to practice medicine only on the side while they devoted more and more time and energy to BioWare, the last had moved into another stage of life. He already had children to support, and didn’t feel he could scale back his medical career to the same degree for this other, far chancier venture. Muzyka and Zeschuk would wind up buying out his share of BioWare in mid-1996.

Well before this event, in the spring of 1995, Activision’s MechWarrior 2: 31st Century Combat hit the gaming world with all the force of the giant killer robot on its box. Thanks not least to Activision’s work in creating bespoke versions of MechWarrior 2 for the many incompatible 3D-accelerator cards that appeared that year, it became by many metrics the game of 1995. Suddenly every publisher wanted a giant-mech game of their own. Muzyka and Zeschuk saw the craze as their most surefire on-ramp to the industry as a new, unproven studio without even an office to their name. They paid a few contractors to help them make a demo, sent it to ten publishers, and started cold-calling them one after another. Their secret weapon, says Muzyka, was “sheer stubbornness and persistence. We just kept calling.” Amazingly, they were eventually offered a development deal by nine out of the ten publishers; suffice to say that mechs were very much in favor that year. Interplay came with the most favorable terms, so the partners signed with them. Just like that, BioWare was a real games studio. Now they had to deliver a real game.

They found themselves some cut-price office space not far from the University of Alberta. Ray Muzyka:

There were only four plugs on the wall. We had a power-up sequence for the computers in the office so that we didn’t blow the circuit breaker for the whole building. Everybody would be like, “I’m on. I’m on. I’m on.” We had found by trial and error that if you turned them on in a certain order, it wouldn’t create a power overload. If you turned on the computers in the wrong order, for sure, it would just flip the switch and you had to run downstairs, get the key, and open up the electrical box. It was an interesting space.

During the first year or so, about a dozen employees worked in the office in addition to the founders. Half of these were the folks who had helped to put together the demo that had won BioWare the contract with Interplay. The other half were a group of friends who had until recently hung out together at a comic-book and tabletop-gaming shop in Grande Prairie, Alberta, some 300 miles northwest of Edmonton; one of their number, a fellow named James Ohlen, actually owned the store. This group had vague dreams of making a CRPG; they tinkered around with designs and code there in the basement. Unfortunately, the shop wasn’t doing very well. Even in the heyday of Magic: The Gathering, it was difficult to keep such a niche boutique solvent in a prairie town of just 30,000 people. Having heard about BioWare through a friend of a friend, the basement gang all applied for jobs there, and Muzyka and Zeschuk hired them en masse. So, they all came down to Edmonton, adopting various shared living arrangements in the cheap student-friendly housing that surrounded the university. Although they would have to make the mech game first, they were promised that there was nothing precluding Bioware from making the CRPG of their dreams at some point down the road if this initial project went well.

Shattered Steel, BioWare’s first and most atypical game ever, was published by Interplay in October of 1996. It was not greeted as a sign that any major new talent had entered the industry. It wasn’t terrible; it just wasn’t all that good. Damning it with faint praise, Computer Gaming World called it “a decent first effort. But if Interplay wants to provide serious competition for the MechWarrior series, the company needs to provide more freedom and variety.” Sales hovered in the low tens of thousands of units. That wasn’t nothing, but BioWare’s next game would need to do considerably better if they were to stay in business. Luckily, they already had something in the offing that seemed to have a lot of potential.

A BioWare programmer named Scott Greig had been tinkering lately with a third-person, isometric, real-time graphics engine of his own devising. He called it the Infinity Engine. Muzyka and Zeschuk had an idea about what they might use it for.

A low background hum was just beginning to build about the possibilities for a whole new sort of CRPG, where hundreds or thousands of people could play together in a shared persistent world, thanks to the magic of the Internet. 3DO’s Meridian 59, the first of the new breed, was officially open for business already, even as Sierra’s The Realm was in beta and Origin’s Ultima Online, the most ambitious of the shared virtual worlds by far, was gearing up for its first large-scale public test. Muzyka and Zeschuk, who prided themselves on keeping up with the latest trends in gaming, saw an opportunity here. Even before Shattered Steel shipped, it had been fairly clear to them that they had jumped on the MechWarrior train just a little bit too late. Perhaps they could do better with this nascent genre-in-the-offing, which looked likely to be more enduring than a passing fancy for giant robots.

They decided to show the Infinity Engine to their friends at Interplay, accompanied by the suggestion that it might be well-suited for powering an Ultima Online competitor. They booked a meeting with one Feargus Urquhart, who had started at Interplay six years earlier as a humble tester and moved up through the ranks with alacrity to become a producer while still in his mid-twenties. Urquhart was skeptical of these massively-multiplayer schemes, which struck him as a bit too far out in front of the state of the nation’s telecommunications infrastructure. When he saw the Infinity Engine, he thought it would make a great fit for a more traditional style of CRPG. Further, he knew well that the Dungeons & Dragons brand was currently selling at a discount. Muzyka and Zeschuk, who were looking for any way at all to get their studio established well enough that they could stop taking weekend shifts at local clinics, were happy to let Urquhart pitch the Infinity Engine to his colleagues in this other context.

Said colleagues were for the most part less enthused than Urquhart was; as we’ve learned all too well by now, the single-player CRPG wasn’t exactly thriving circa 1996. Nor was the Dungeons & Dragons name on a computer game any guarantee of better sales than the norm in these latter days of TSR. Yet Urquhart felt strongly that the brand was less worthless than mismanaged. There had been a lot of Dungeons & Dragons computer games in recent years — way too many of them from any intelligent marketer’s point of view — but they had almost all presumed that what their potential buyers wanted was novelty: novel approaches, novel mechanics, novel settings. As they had pursued those goals, they had drifted further and further from the core appeal of the tabletop game.

Despite TSR’s fire hose of strikingly original, sometimes borderline avant-garde boxed settings, the most popular world by far in which to actually play tabletop Dungeons & Dragons remained the Forgotten Realms, an unchallenging mishmash of classic epic-fantasy tropes. The Forgotten Realms was widely and stridently criticized by the leading edge of the hobby for being fantasy-by-the-numbers, and such criticisms were amply justified in the abstract. But those making them failed to reckon with the reality that, for most of the people who still played tabletop Dungeons & Dragons, it wasn’t so much a vehicle for improvisational thespians to explore the farthest realms of the imagination as it was a cozy exercise in dungeon delving and monster bashing among friends; the essence of the game was right there in its name. For better or for worse, most people still preferred good old orcs and kobolds to the mind-bending extra-dimensional inhabitants of a setting like Planescape or the weird Buck Rogers vibe of something like Spelljammer. The Forgotten Realms were gaming comfort food, a heaping dish of tropey, predictable fun. And the people who played there wouldn’t have had it any other way.

And yet fewer and fewer Dungeons & Dragons computer games had been set in the Forgotten Realms since the end of the Gold Box line. (Descent to Undermountain would be set there, but it had too many other problems for that to do it much good.) SSI and their successors had also showed less and less fidelity to the actual rules of Dungeons & Dragons over the years. The name had become nothing more than a brand, to be applied willy-nilly to whatever struck a publisher’s fancy: action games, real-time-strategy games, you name it. In no real sense were you playing TSR’s game of Dungeons & Dragons when you played one of these computer games; their designers had made no attempt to implement the actual rules found in the Player’s Handbook and Dungeons Master’s Guide. It wasn’t clear anymore what the brand was even meant to stand for. It had been diluted to the verge of meaninglessness.

But Feargus Urquhart was convinced that it was not yet beyond salvation. In fact, he believed that the market was ready for a neoclassical Dungeons & Dragons CRPG, if you will: a digital game that earnestly strove to implement the rules and to recreate the experience of playing its tabletop inspiration, in the same way that the Gold Box line had done. Naturally, such a game would need to take place in the tried-and-true Forgotten Realms. This was not the time to try to push gamers out of their comfort zone.

At the same time, though, Urquhart recognized that it wouldn’t do to simply re-implement the Gold Box engine and call it a day. Computer gaming had moved on from the late 1980s; people expected a certain level of audiovisual razzle-dazzle, wanted intuitive and transparent interfaces that didn’t require reading a manual to learn how to use, and generally preferred the fast-paced immediacy of real-time to turn-based models. If it was to avoid seeming like a relic from another age, the new CRPG would have to walk a thin line, remaining conservative in spirit but embracing innovation with gusto in all of its granular approaches. The ultimate goal would not be to recreate the Gold Box experience. It must rather be to recreate the same tabletop Dungeons & Dragons experience that the Gold Box games had pursued, but to embrace all of the affordances of late-1990s computers in order to do it even better — more accurately, more enjoyably, with far less friction. Enter the Infinity Engine.

But Urquhart’s gut feeling was about more than just a cool piece of technology. He had served as the producer on Shattered Steel, in which role he had visited BioWare several times and spent a fair amount of time with the people there. Thus he knew there were people in that Edmonton office who still played tabletop Dungeons & Dragons regularly, who had forged their friendships in the basement of a tabletop-gaming shop. He thought that a traditionalist CRPG like the one he had in mind might be more in their wheelhouse than any giant-robot action game or cutting-edge shared virtual world.

He felt this so strongly that he arranged a meeting with Brian Fargo, the Big Boss himself, whose soft spot for the genre that had put Interplay on the map a decade earlier was well known. When he was shown the Infinity Engine, Fargo’s reaction was everything Urquhart had hoped it would be. What sprang to his mind first was The Faery Tale Adventure, an old Amiga game whose aesthetics he had always admired. “It didn’t look like a bunch of building blocks,” says Fargo today of the engine that Urquhart showed him in 1996. “It looked like somebody had free-hand-drawn every single screen.”

As Urquhart had anticipated would be the case, it wasn’t hard for Fargo to secure a license from the drowning TSR to make yet another computer game with the name of Dungeons & Dragons on it. The bean counters on his staff were not excited at the prospect; they didn’t hesitate to point out that Interplay already had Fallout and Descent to Undermountain in development. Just how many titles did they need in such a moribund genre? They needed at least one more, insisted Fargo.

BioWare’s employees were astonished and overjoyed when they were informed that a chance to work on a Dungeons & Dragons CRPG had fallen into their laps out of the clear blue sky. James Ohlen and his little gang from Grande Prairie could scarcely have imagined a project more congenial to their sensibilities. Ohlen had been running tabletop Dungeons & Dragons campaigns for his friends since he was barely ten years old. Now he was to be given the chance to invent one on the computer, one that could be enjoyed by the whole world. It was as obvious to Urquhart as it was to everyone at BioWare that the title of Lead Designer must be his. He called his initial design document The Iron Throne. When a cascade of toilet jokes rained down on his head in response, Urquhart suggested the more distinctive name of Baldur’s Gate, after the city in the Forgotten Realms where its plot line would come to a climax.

The staff of BioWare, circa 1997. (Note the Edmonton Oilers jersey at front and center.) “It’s 38 kids I barely recognize, myself included,” says Lukas Kristjanson, who along with James Ohlen wrote most of the text in the game. “I look at that face and think, ‘Man, you did not know what you were doing.'”

BioWare eagerly embraced Urquhart’s philosophy of being traditionalist in spirit but modern in execution. The poster child for the ethic must surely be Baldur’s Gate’s approach to combat. BioWare faithfully implemented almost every detail of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules, complete with all of the less intuitive legacies of Gary Gygax, such as the armor-class statistic that goes down rather than up as it gets better. But, knowing that a purely turn-based system would be a very hard sell in the current market, they adopted a method of implementing them that became known as “real-time-with-pause.” Like much in Baldur’s Gate, it was borrowed from another game, a relatively obscure 1992 CRPG called Darklands, which was unique for being set in Medieval Germany rather than a made-up fantasy world.

Real-time-with-pause means that, although the usual tabletop rounds and turns are going on in the background, along with the expected initiative rolls and to-hit rolls and all the rest, it all takes place seamlessly on the computer — that’s to say, without pausing between turns, unless and until the player stops the action manually to issue new orders to her party. James Ohlen:

Ray [Muzyka] was a big fan of turn-based games, the Gold Box games, and my favorite genre was real-time strategy; I played Warcraft and Starcraft more than you can imagine. So, [real-time-with-pause] came from having to have a real-time game that satisfied fans of that genre, but also satisfied turn-based fans. Maybe I shouldn’t say it, but I was never a fan of Fallout. I liked the story and the world, but the fact it paused and took turns for moving, I never liked that. RPGs are about immersing you in their world, so the closer you get to the feeling of real the better.

The project was still in its earliest stages when Diablo dropped. “I remember when Diablo came out, the whole office shut down for a week,” says James Ohlen. Needless to say, many another games studio could tell the same tale.

The popularity of Blizzard Entertainment’s game was the first really positive sign for the CRPG genre as a whole in several years. In this sense, it was a validation for Baldur’s Gate, but it was also a risk. On a superficial level, the Diablo engine didn’t look that different from the Infinity Engine; both displayed free-scrolling, real-time environments from an isometric point of view. Blizzard’s game, however, was so simplified and streamlined that it prompted endless screaming rows on the Internet over whether it ought to qualify as a “real” CRPG at all. There was certainly no real-time-with-pause compromise in evidence here; Diablo was real-time, full stop. Given its massive success, someone at Interplay or BioWare — or more likely both — must surely have mused about dropping most of the old-school complexity from Baldur’s Gate and adopting Diablo as the new paradigm; the Infinity Engine would have been perfectly capable of bringing that off. But, rather remarkably on the face of it, no serious pressure was ever brought to bear in that direction. Baldur’s Gate would hew faithfully to its heavier, more traditionalist vision of itself, even as the people who were making it were happily blowing off steam in Diablo. The one place where Diablo did clearly influence Baldur’s Gate was a networked multiplayer mode that was added quite late in the development cycle, allowing up to six people to play the game together. Although BioWare deserves some kudos for managing to make that work at all, it remains an awkward fit with such a text- and exposition-heavy game as this one.

As James Ohlen mentions above, the BioWare folks were playing a lot of Blizzard’s Warcraft II as well, and borrowing freely from it whenever it seemed appropriate. Anyone who has played a real-time-strategy game from the era will see many traces of that genre in Baldur’s Gate: the isometric graphics, the icons running around the edges of the main display, your ability to scroll the view independently of the characters you control, even the way that active characters are highlighted with colored circles. The Infinity Engine could probably have powered a fine RTS game as well, if BioWare had chosen to go that route.

Even more so than most games, then, Baldur’s Gate was an amalgamation of influences, borrowing equally from James Ohlen’s long-running tabletop Dungeons & Dragons campaign and the latest hit computer games, along with older CRPGs ranging from Pool of Radiance to Darklands. I hate to use the critic’s cliché of “more than the sum of its parts,” but in this case it may be unavoidable. “If you’re a Dungeons & Dragons fan, you feel like you’re playing Dungeons & Dragons, but at the same time it felt like a modern game,” says James Ohlen. “It was comparable to Warcraft and Diablo in terms of the smoothness of the interface, the responsiveness.”

Baldur’s Gate started to receive significant press coverage well over a year before its eventual release in December of 1998. Right from the first previews, there was a sense that this Dungeons & Dragons computer game was different from all of the others of recent years; there was a sense that this game mattered, that it was an event. The feeling was in keeping with — and to some extent fed off of — the buzz around Wizards of the Coast’s acquisition of TSR, which held out the prospect of a rebirth for a style of play that tabletop gamers may not have fully recognized how much they’d missed. Magic: The Gathering was all well and good, but at some point its zero-sum duels must begin to wear a little thin. A portion of tabletop gamers were feeling the first inklings of a desire to return to shared adventures over a long afternoon or evening, adventures in which everyone got to win or lose together and nobody had to go home feeling angry or disappointed.

A similar sentiment was perhaps taking hold among some digital gamers: a feeling that, for all that Diablo could be hella fun when you didn’t feel like thinking too much, a CRPG with a bit more meat on its bones might not go amiss. Witness the relative success of Fallout in late 1997 and early 1998; it wasn’t a hit on the order of Diablo, no, but it was a solid seller just the same. Even the miserable fiasco that was Descent to Undermountain wasn’t enough to quell the swelling enthusiasm around Baldur’s Gate. Partially to ensure that nothing like Undermountain could happen again, Brian Fargo set up a new division at Interplay to specialize in CRPGs. He placed it in the care of Feargus Urquhart, who named the division and the label Black Isle, after the Black Isle Peninsula in his homeland of Scotland.

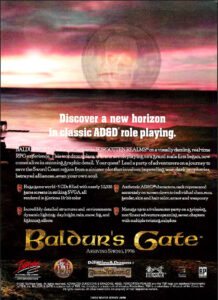

Interplay was already running full-page advertisements like this one in the major magazines before 1997 was out. Note the emphasis on “true role-playing on a grand scale” — i.e., not like that other game everyone was playing, the one called Diablo.

The buzz around Baldur’s Gate continued to build through 1998, even as a planned spring release was pushed back to the very end of the year. A game whose initial sales projections had been on the order of 100,000 units at the outside was taking on more and more importance inside the executive suites at Interplay. For the fact was that Interplay as a whole wasn’t doing very well — not doing very well at all. Brian Fargo’s strategy of scatter-bombing the market with wildly diverse products, hoping to hit the zeitgeist in its sweet spot with at least a few of them, was no longer paying off for him. As I mentioned at the opening of this article, Interplay’s last real hit at this stage had been Descent in 1995. Not coincidentally, that had also been their last profitable year. The river of red ink for 1998 would add up to almost $30 million, a figure one-quarter the size of the company’s total annual revenues. In October of 1998, Fargo cut about 10 percent of Interplay’s staff, amounting to some 50 people. (Most of them had been working on Star Trek: The Secret of Vulcan Fury, a modernized follow-up to the company’s classic Star Trek: 25th Anniversary and Judgment Rites adventure games. Its demise is still lamented in some corners of Star Trek and gaming fandom.)

Fargo was increasingly seeing Baldur’s Gate as his Hail Mary. If the game did as well as the buzz said it might, it would not be able to rescue his sinking ship on its own, but it would serve as much-needed evidence that Interplay hadn’t completely lost its mojo as its chief executive pursued his only real hope of getting out of his fix: finding someone willing to buy the company. The parallels with the sinking ship that had so recently been TSR doubtless went unremarked by Fargo, but are nonetheless ironically notable.

BioWare’s future as well was riding on what was destined to be just their second finished game. The studio in the hinterlands had grown from 15 to 50 people over Baldur’s Gate’s two-year development cycle, leaving behind as it did so its electrically-challenged hovel of an office for bigger, modestly more respectable-looking digs. Yet appearances can be deceiving; BioWare was still an unproven, unprofitable studio that needed its second game to be a hit if it was ever to make a third one. It was make-or-break-time for everyone, not least Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk. If Baldur’s Gate was a hit, they might never have to take up their stethoscopes again. And if it wasn’t… well, they supposed it would be back to the clinic for them, with nothing to show for their foray into game development beyond a really strange story to tell their grandchildren.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Beneath a Starless Sky: Pillars of Eternity and the Infinity Engine Era of RPGs by David L. Craddock, Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay, and Online Game Pioneers at Work by Morgan Ramsay. Computer Gaming World of December 1996, January 1997, October 1997, January 1998, April 1998, January 1999, and June 1999; Retro Gamer 110 and 188; PC Zone of December 1998.

Online sources include BioWare’s current home page, “How Bioware revolutionised the CRPG” by Graeme Mason at EuroGamer, “IGN Presents the History of BioWare” by Travis Fahs, “The long, strange journey of BioWare’s doctor, developer, beer enthusiast” by Brian Crecente at Polygon, Jeremy Peel’s interview with James Ohlen for Rock Paper Shotgun, and GameSpot’s vintage review of Descent to Undermountain.

I also made use of the Interplay archive donated by Brian Fargo to the Strong Museum of Play.

The CRPG Renaissance, Part 3: TSR is Dead…

“How do you make a small fortune in tabletop gaming?” runs an old joke.

The punchline, of course, is that you come to that market with a large one.

The tabletop truly is a brutally challenging place to try to earn money, one which you have to be either wildly deluded or unbelievably passionate to even contemplate entering. Nevertheless, people have been making a go of it there for quite some decades by now. We’ll give them the benefit of the doubt and assume that love rather than mental illness is the motivating force. For, whatever else you can say about these folks, nobody is more passionate about their hobby than old-school tabletoppers.

If you do dare to dream of making real money on the tabletop, there are two ways you might envision doing so. One is to strike gold with a once-in-a-blue-moon mass-market perennial of the sort that eventually winds up in every other family’s closet: a Monopoly, a Scrabble, a Clue, a Trivial Pursuit. Under this model, you sell that one game to tens if not hundreds of millions of people, the majority of whom might not buy another board game for five or ten years after buying yours.

The other pathway to profit — or at least to long-term survival — is to score a hit in the hobbyist market. Here your sales ceiling is much lower. But, because you’re selling to people who see tabletop gaming as a lifestyle rather than a gambit to divert the kids on a rainy afternoon, you can potentially keep selling them additions to the same basic game for years and years, turning it into not so much a single product as a whole ecosystem of same. It’s a tougher row to hoe in that it requires an ongoing effort on your part to come up with a steady stream of new content that appeals to your customers, but it’s marginally more achievable than winning the lottery that is the mass market.

That said, any given game need not be exclusively of the one sort or the other. Crossover hits are possible and even increasingly common. In recent decades, several hobbyist games — among them titles such as Catan, Carcassonne, and Ticket to Ride — have proved to possess the necessary blend of relatability, simplicity, and fun to be sold in supermarkets and greeting-card shops in addition to the scruffy hobbyist boutiques.

Way back in the early 1980s, Dungeons & Dragons was successful enough that its maker, the Lake Geneva, Wisconsin-based TSR, dared to wonder whether that game might be able to make the leap to the mainstream, however strange it may have seemed to imagine that an exercise in elaborate make-believe and tactical monster-fighting might have the same sort of legs as Monopoly. After all, despite its complexity and subject matter, Dungeons & Dragons was already far more culturally visible than Monopoly, a fixture of school cafeterias and anti-Satanic evangelical sermons alike.

Alas, it was not to be. The Dungeons & Dragons wave crested in 1982, after which the bandwagon jumpers began to jump off the wagon again. True mass-market success was probably never in the cards for a company whose acronym stood for “Tactical Studies Rules.” Luckily for TSR, they retained a core group of loyalists who were willing to splash out considerable sums of money on their hobby. Indeed, for a goodly while it seemed like they would snatch up as much new Dungeons & Dragons product as TSR cared to throw at them.

A new era of Dungeons & Dragons merchandising dawned in 1984, when TSR rolled out a trans-media property known as Dragonlance: twelve individual adventure modules, plus two source books and even a strategic board game, all meant to allow a group of players to interactively experience an epic tale of fantasy war that could also be read about in a trilogy of thick conventional novels, the first of their kind that TSR had ever published. It was a brilliant conception in its way, and it became hugely popular with the fan base, heralding a slow shift in TSR’s rhetoric around Dungeons & Dragons. In the past, it had been promoted as a game of free-flowing imagination, primarily a system for making up your own worlds and stories. In the future, the core rules would be marketed as a foundation that you built upon not so much with your own creativity as with other, more targeted TSR products: settings to inhabit, adventures to go through in those settings, new rule books to make a complicated game still more complicated.

The transaction was not so cynical as I might have made it sound. The products themselves were often excellent, thanks to TSR’s dedicated and imaginative staff, and many or most fans felt they got fair value for their ongoing investment. Yet the fact remained that this was also TSR’s only viable way of remaining solvent after the mainstream culture had dismissed Dungeons & Dragons as a weird, kitschy fad or a shorthand for abject nerdiness.

As it was, though, TSR coasted along fairly comfortably on these terms for quite some years. The Dungeons & Dragons supplements continued to sell, even after there were so many of them that it was difficult to see how even the most committed zealot could possibly find the time to get more than a tiny percentage of them to the table. (TSR doubtless benefited from the fact that a lot of fans could get pleasure out of the source books without ever using them for their intended purpose: a surprising number of people over the years have told me that they liked to read such books just to appreciate the meticulous world-building.) The release of a modestly revised “Second Edition” of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons in 1989 sent the fans scrambling to re-buy a game they already owned, if for no other reason than to stay compatible with that fire hose of adventures and supplements. Meanwhile TSR found an unexpectedly rich new revenue stream in the many Dungeons & Dragons novels that followed in the wake of that first Dragonlance trilogy; the sales of virtually any of these dwarfed the unit sales of the typical gaming product, while the most popular of all among them, such as R.A. Salvatore’s tales of the dark-elf ranger Drizzt, climbed high on the New York Times bestseller charts. Add to this a deal with SSI to make Dungeons & Dragons-branded computer games, five of which sold more than 100,000 copies from 1988 to 1991. Between the novels and the computer games, Dungeons & Dragons had become as much an abstract lifestyle brand as a concrete tabletop game by the beginning of the 1990s.

It was at about this time that it all started to go wrong — subtly wrong at first, then obviously, and then disastrously. The root of the rot is hard to pinpoint precisely, as these things always are.

Some people point as far back as 1985, when Lorraine Williams, a wealthy heiress who owed her fortune primarily to the Buck Rogers character of comic-book, movie-serial, and television fame, ousted Gary Gygax and took over the company in a palace coup. She is not, to say the least, a highly regarded figure among old-school Dungeons & Dragons fandom. For our part, we need to tread cautiously here; there’s an ugly undertone of gatekeeping and/or misogyny that clings to many fan narratives about Williams’s tenure at the head of TSR. Nonetheless, it is true that she had little intrinsic interest in Dungeons & Dragons; in fact, she sometimes seemed to regard the game’s fans with something perilously close to contempt. In the beginning, TSR was in a strong enough position to overcome her estrangement from the market she served. Later on, this would no longer be the case.

Other people prefer to point to 1991, when a new publisher called White Wolf released a tabletop RPG called Vampire: The Masquerade, which portrayed its titular monsters not as blood-sucking horrors but as sexy lovers of the night straight out of an Anne Rice novel. That, combined with its rules-light approach, attracted a whole new demographic who wouldn’t have been caught dead battling hobgoblins in a fantasy dungeon: too-cool-for-school Goths, who gave free rein to their inner fiends around the gaming table in between Cure concerts. Even in its allegedly streamlined second edition, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons looked stodgy and pedantic to the eyes of many gamers when compared with its younger, slicker competition. For arguably the only time in the entire history of the tabletop RPG, there was real reason to question whether Dungeons & Dragons would continue to be the unrivaled giant of the field going forward. Sales of TSR’s rules and supplements fell off gradually, while sales on the digital front fairly fell off a cliff: no other Dungeons & Dragons computer game from SSI would come anywhere close to sales of 100,000 units after Eye of the Beholder in 1991.

Then, just when it looked like Dungeons & Dragons was at risk of losing its position at the top of the tabletop-RPG pile, another sort of game entirely came along to kick the whole stack right out from under all of them. In August of 1993, a little card game called Magic: The Gathering, designed by a graduate student in combinatorics named Richard Garfield and bearing the logo of a heretofore unsuccessful publisher of tabletop-RPG material named Wizards of the Coast, was debuted at the Gen Con trade show in Wisconsin — a show which had been started by Gary Gygax all the way back in 1968, and which was still put on every year by TSR. At this 26th installment of Gen Con, however, the talk was all about Magic rather than Dungeons & Dragons. Allen Varney later wrote in TSR’s own house magazine Dragon how

people clustered three deep around the Wizards of the Coast table, craning to see the ongoing demonstrations of this game. Everywhere I went I saw someone playing it. In discussing it, some players showed reserved admiration, others enthusiasm, but body language told more than words. Everyone hunched forward intently, the way you do in deep discussions of politics or religion. Onlookers and devoted fans alike felt compelled to grapple with the idea of this game. It achieved more than just a commercial hit; it redefined gamers’ perspectives on their hobby.

The scenes that Varney witnessed were a microcosm of what was about to happen to hobbyist gaming in general, as tabletop fantasy, for so many years a relatively stable market, was hit by this new, profoundly destabilizing force.

We can point to any number of grounds for Magic’s enormous appeal. Many of them boil down to convenience: it was quick to set up and could be played in twenty minutes or so by just two people, without either of them having to read much in the way of rules beyond what was printed on the cards themselves. (Compare this with needing to assemble at least four or five friends to play Dungeons & Dragons, as well as with that game’s hundreds of pages of rules, the crushing weight of preparation and responsibility it put on the Dungeon Master who guided the session, and its equally extreme demands of time; many a Dungeons & Dragons party hadn’t yet decided what equipment to carry into the dungeon by the time twenty minutes had elapsed.) Then, too, the Magic cards were beautifully illustrated, such that collecting them could become an end unto itself. Finally, add to all of this a feeling that had been setting in even before that pivotal Gen Con: that Dungeons & Dragons had become old hat, an artifact of the last two decades rather than this one. A new generation of gamers craved something fresh. For better or for worse, it seemed that Magic was that thing.

Magic became an unprecedented phenomenon in tabletop gaming, its astounding growth curve eclipsing by a veritable order of magnitude even the early days of Dungeons & Dragons. More than TSR ever had, Wizards of the Coast had well and truly mastered the art of making money in hobbyist gaming by selling the same group of people an infinite stream of content for the same basic game. They had mastered it so well, in fact, that there wasn’t much room left for TSR; a gamer who spent all of his allowance or paycheck on new Magic decks simply didn’t have any money left to give to Dungeons & Dragons.

Like many other shell-shocked publishers in the tabletop-RPG space, TSR tried to fight back by quite literally playing Wizards of the Coast’s own game. Already in 1994, they released a collectible card game of their own called Spellfire. It’s doubtful whether it would have been able to overcome Magic’s first-mover advantage even if its use of recycled, clashing artwork from previous eras of Dungeons & Dragons hadn’t made it look so much like the rushed knockoff product it was. TSR mustered a modicum more creativity for 1995’s Dragon Dice, which replaced collectible cards with — you guessed it — collectible dice. But it too failed to attract the critical mass of players it needed in order to become self-sustaining. Collectible anything games writ large were a zero-sum game, one in which all of the cards seemed to belong to Wizards and Magic.