I feel very comfortable working in a company where you can’t touch anything.

— Walter Forbes

At the beginning of 1996, Sierra On-Line was still basking in the success of the previous summer’s Phantasmagoria, the best-selling game it had ever published. With revenues of $158.1 million and profits of $16 million in 1995, the company was bigger and richer than it had ever been. In light of all this, absolutely nobody anticipated the press release that went out from Sierra’s new headquarters in Bellevue, Washington, on February 20. It announced that Sierra would soon “merge with CUC International, Inc., a technology-driven retail and membership-services company that provides access to travel, shopping, auto, dining, home-improvement, financial, and other services to 40 million consumers worldwide. Sierra stockholders will receive 1.225 shares of CUC common stock for each share of Sierra common stock. The transaction is valued at approximately $1.06 billion. The merger is subject to stockholder approval and other customary closing conditions.”

As this bombshell filtered down to the gaming sites that were popping up all over the young Web, and eventually to the laggardly print magazines, one question was first on the lips of every gamer who read about it. Just who or what was this CUC International anyway? Or, to frame the question differently: if CUC was such a big wheel, why had no one ever heard of it, and why did CUC itself seem to have such a hard time explaining what it actually did?

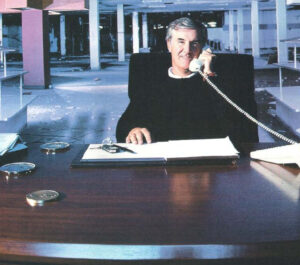

Time would show the answers to both of those questions to be more complicated and fraught than anyone could have expected. Still, it was clear from the outset that the path to understanding must pass through CUC’s CEO, a sprightly, dapper-looking man of business named Walter Forbes. This particular Forbes was not a member of the wealthy family who owned and operated Forbes magazine, one of the business and investment world’s primary journals of record. That fact notwithstanding, he had been born into decidedly privileged circumstances, and would certainly not have looked out of place with that other Forbes family at a blue-blood country club. Walter Forbes was a titan of industry straight out of Central Casting, from his artfully arranged salt-and-pepper coiffure to the gleaming Gucci loafers he donned on “casual” days. He was as convincing a figure as has ever walked into a corporate boardroom. In a milieu where looking the part of a General Patton of business was a prerequisite to joining the war for hearts, minds, and wallets, Forbes had the role down pat. With a guy like this at its head, how could CUC be anything but amazing? And how could little Sierra count itself anything but fortunate to become a part of his burgeoning empire?

As Forbes himself told the story to a wide-eyed journalist from Wired magazine in 1997, it had all begun for him back in 1973, when, having recently graduated from Harvard Business School, he was eating dinner one evening with some friends and some of his former professors. Somehow the discussion turned to the future of shopping. “Wouldn’t it be neat if we could bypass stores and send products from the manufacturer to the home, and people would use computers to shop?” Forbes recalled “someone” at the table saying. “Everyone forgot about what we talked about that night. Except me.”

Forbes envisioned a scenario in which brick-and-mortar retailers, those traditional middlemen of the chain of commerce, would be replaced by digital storefronts operated by his own company, which was founded in 1973 under the name of Comp-U-Card. According to his own testimony, he mooted various impractical schemes for priming the e-commerce pump before the technology of telecommunications finally showed signs of catching up with at least some of his aspirations circa 1979, the year that the pre-Web commercial online services The Source and CompuServe made their debut. Now favoring the acronym CUC over the “Comp-U-Card” appellation — needless to say, nobody would rush to embrace that name today; the evolution of language can be a dangerous thing for corporate branders — Forbes took his company public in 1983, with an IPO that came in at $100 million. His business plan at the time, at least as he explained it fourteen years later, rings almost eerily prescient.

Manufacturers would simply send information about their products to [Forbes’s] database company, which would aggregate the data, organize it, and then present it to consumers in an engaging way. When a shopper ordered something, the manufacturer would be notified to ship it directly to the consumer’s home. Since no retailer would be involved, the customer would simply pay the wholesale price, plus shipping charges. The database company would make almost no money on the transactions. Rather, it would make its money by charging the consumer a flat annual membership fee — typically $49 — for access to the data and the chance to buy at such low prices.

Apart from a few details here and there, this is the way that Amazon, the 800-pound gorilla of modern online retail, operates today, right down to the “buyers club” where it makes most of its real money.

But here’s where the waters surrounding Walter Forbes and CUC start to get muddy. (I do hope you packed your diving goggles, because there are a lot of such waters ahead.) For the first ten years after the IPO, CUC actually took very little in the way of concrete steps in pursuit of the proto-Amazonian dream that Forbes had supposedly been nursing since 1973. Instead it administered offline shopping clubs that were marketed via bulk-rate post and telephone cold-calling. This was a sector of the consumer economy that thrived mostly on fine print and the failure of its often elderly customers to do their due diligence, being just one step removed from timeshares on the continuum of shady business models that never turn out to deliver quite what their customers think they are getting; in fact, timeshares soon became a part of CUC’s portfolio too. CUC sold its shopping clubs and other services as turnkey packages that could be purchased and branded by other corporations, thus partially explaining why so few people had ever heard of the company even fourteen years after its IPO. It wasn’t above using guile to retain customers, such as quietly signing them up for automatic recurring billing plans — charges that, it hoped, some portion of its customers who thought they were just making a one-time payment would fail to notice on their credit-card statements. Even the fawning profile in Wired had to acknowledge how close to the ethical edge CUC was prepared to fly.

If a customer takes the trouble to call and quit, the CUC telephone operator goes into what any football fan would recognize as a prevent defense. The operator frantically starts explaining the value of the service, then often sacrifices a $20 coupon or check as a bribe to stick around. They will give up ground, but [will] do anything to keep you from reaching that goal line.

As late as the year that CUC acquired Sierra On-Line, it was the offline shopping clubs that were still the heart of its revenue stream, the subject that its annual report for the year chose to open with and to return to again and again.

CUC International is a leading technology-driven, membership-based consumer services company, providing approximately 66.3 million members with access to a variety of goods and services. The Company provides these services as individual, wholesale, or discount program memberships. These memberships include such components as shopping, travel, auto, dining, home improvement, lifestyle, vacation-exchange [i.e., timeshares], credit-card and checking-account enhancement packages, financial products and discount programs. The Company also administers insurance-package programs which are generally combined with discount shopping and travel for credit-union members, distributes welcoming packages which provide new homeowners with discounts for local merchants, and provides travelers with value-added tax refunds. The Company believes it is the leading provider of membership-based consumer services of these types in the United States.

The Company solicits members for many of its programs by direct marketing and by using a direct sales force calling on financial institutions, fund-raising charitable institutions and associations…

The Company offers Shoppers Advantage, Travelers Advantage, AutoVantage, Dinner on Us Club, PrivacyGuard, Buyers Advantage, Credit Card Guardian, and other membership services. These benefits are offered as individual memberships, as components of wholesale membership enhancement packages and insurance products, and as components of discount-program memberships. For the fiscal year ended January 31, 1997, approximately 536 million solicitation pieces were mailed, followed up by approximately 70 million telephone calls.

Walter Forbes’s digital aspirations that got Wired so hot and bothered are mentioned only in passing in the report: “Some of the Company’s individual memberships are available online to interactive computer users via major online services and the Internet’s World Wide Web.”

Forbes first became associated with Sierra in 1991, when he agreed to join the company’s board. Ken Williams, Sierra’s co-founder and CEO, considered this a major coup, a sign that his little publisher of computer games was really going places in this new decade of multimedia and cyber-everything. He was excited even though, as he admits in his recent memoir, he “never completely understood Walter’s business. To this day, I can’t completely tell you what it was. There were components of it that made sense — for instance, they owned a company called RCI that facilitated timeshare swapping. They also operated a series of discount shopping clubs, where customers would pay an annual subscription fee, allowing them to buy products at near-wholesale prices. Whatever it was, they were certainly doing something right. They had $2 billion in revenue and over $200 million in profit.”

The voice of Forbes whispering in Ken Williams’s ear was a hidden motivator behind the spate of acquisitions that the latter pursued during the first half of the 1990s, which saw the American educational-software developer Bright Star, the French adventure-games maker Coktel Visions, the British strategy house Impressions, and the American sim specialists Papyrus and subLOGIC all entering the Sierra tent. Having thus hunted down and captured so much smaller prey with Forbes at his side, Williams perhaps shouldn’t have been surprised when his trusted advisor started eying his own company with a hungry look. Nevertheless, when Forbes broached the subject with Ken’s wife Roberta Williams, the designer of Sierra’s flagship King’s Quest series as well as Phantasmagoria and many other adventure and children’s games, she at least was taken aback.

“Have you and Ken ever thought about selling Sierra?” he asked her out of the blue one day in the lobby of the Paris hotel where they happened to be attending a board-of-directors meeting. (An insatiable connoisseur of French food and wine, Forbes had had enough sway with Ken to convince him to hold the meeting at this distant and expensive location.)

“No,” Roberta answered shortly. “We’re not interested.”

“But if you ever were, what sort of price would you be looking at?”

“A lot,” Roberta replied, then walked away as quickly as decorum allowed. She had the discomfiting feeling that Forbes was a predator probing for a flock’s weak link, and she was determined that it wouldn’t be her.

But when Forbes brought the subject up in a more formal way, at another Sierra board meeting closer to home on February 2, 1996, Roberta’s husband proved far more receptive than she had been.

The only detailed insider account of what happened next and why is the one written by Ken Williams. Needless to say, this must raise automatic red flags for any historian worth his salt. And yet his memoir does appear to be about as even-handed as anyone could possibly expect under the circumstances. To his credit, he owns up to many of his own mistakes with no hesitation whatsoever. While we would be foolish to take his account as the unvarnished gospel truth, he doesn’t strike me as a completely unreliable witness by any means. I think we can afford to take much if not all of what he writes at face value as we ask ourselves what led him to the most monumental decision of his life, excepting only the decision to found Sierra in the first place all the way back in 1980.

To begin with, Williams admits forthrightly that he was quite simply tired at this juncture of his life, and that his sense of exhaustion made the prospect of selling out and taking a step back more appealing than it might have been just a few years earlier. His fatigue is eminently understandable: Sierra had consumed almost his every waking hour for over fifteen years by this point. He tells us that people had been telling him for ages that he “needed to delegate more, but it just wasn’t in my personality to do so.” More and more as the games got more expensive and the stakes for every new release higher, Williams had felt forced to play the role of the corporate heavy.

My visits to Sierra’s development teams were occasionally liked, but not very often. Left to their own devices, the teams would agonize over the games forever. Asking an artist to compromise quality in order to bring the art in on budget is not a win-win for either of us, but it’s something I had to do every day. Shutting down projects, ruining dreams, staring endlessly at spreadsheets, riding on airplanes. That was my life.

Sierra had become rather notorious these last few years for shipping games before they were ready. At the end of the day, the decision to do so was Ken Williams’s, but he often believed he had no real choice in the matter at all. For Sierra was now a publicly traded company, and he felt it couldn’t afford the hit to the stock price that would result from not having Game X on the shelves in time for some given Christmas shopping season. Now, the skeptical reader might argue that there were surely ways to improve internal processes such that games weren’t continually falling behind schedule, going over budget, and winding up caught in the “ship it now or die” trap — and such a reader would be absolutely right. But that doesn’t change the state of play on the ground from the perspective of Ken Williams, who was not a good delegater and seemed to lack the turn of mind that was required to implement more rigorous methodologies of game development. This situation being what it was, he hoped that the (apparently) deep pockets of CUC would insulate Sierra somewhat from the vagaries of stock prices and holiday seasons, would give him more leeway to grant a promising game the six more months in the oven it needed to become a great one.

In addition to all of the above, Williams leans heavily on his “fiduciary duty” to his shareholders to explain why he was so willing and even eager to embrace Forbes’s offer. As CEO, he says, he was obliged to maximize his shareholders’ return on their investment, regardless of his personal feelings: “To state it simply, the decision wasn’t mine to make. I had a responsibility to the company’s true owners.” Alas, it’s here that I do have to part ways somewhat with the idea of Ken Williams as a completely reliable witness; this statement does begin to veer into self-serving territory.

The majority of Sierra’s shareholders were of the passive stripe, who had little understanding of the company’s business and were thus very ready to listen when the CEO who had just delivered a record profit told them what he thought they ought to do. And Ken Williams made it abundantly clear to these shareholders that he thought they ought to take the deal.

Yet he did so over the objections of virtually everyone he talked to who did understand Sierra’s business reasonably well. His board of directors was unanimous in its opposition, with the exception only of the member named Walter Forbes. Mike Brochu, Sierra’s hard-nosed president and chief operating officer, who was in many ways the architect of the company’s last couple of years of solid growth and profitability, saw no reason for it to surrender its independence now, just when things were going so swimmingly for it.

Likewise, Jerry Bowerman, a former investment banker who was now vice president for product development, says today that he “pleaded” with Williams to at the very least take a longer, harder look at Forbes and his “company that sells coupons” than he had shown any interest in doing prior to this point; something about CUC, Bowerman says, “made [the] hair stand up on the back of my neck.” In particular, he saw a communist convention worth of red flags in CUC’s habit of just beating its earnings expectations on Wall Street every single quarter: “That’s categorically impossible. Does not happen.” But somehow with CUC it did. “He has a fiduciary responsibility, and the board has a fiduciary responsibility, to take the offer seriously,” acknowledges Bowerman. “What [Williams] never did do was, like, hire an investment bank to say, is this actually a fair offer?”

Even Ken’s own wife Roberta was dead-set against the acquisition: “When Walter asked me, did we ever think of selling the company, and I said no, I meant it. I always had a little bit of intuition about Walter. Not that he was a crook or anything like that. Just… take him with a grain of salt.”

Ken Williams normally listened to his wife. As lots of people knew then and will happily tell you today, Roberta was often the final arbiter of what did and didn’t happen at Sierra, in discussions that took place around the Williams family dinner table long after the lights in the boardroom and executive suites had been extinguished. In this case, however, he ignored her advice, as he did that of so many of his professional colleagues. Instead of taking Walter Forbes with a grain of salt, he took his deal — signed on the dotted line, with no questions asked, selling the company that had been his life’s work to another one whose business model and revenue streams were almost entirely opaque to him.

Doing so was without a doubt the worst decision Ken Williams ever made in his business career, but it wasn’t totally out of character for the man. There’s a theory in pop psychology that every alpha male is really looking to become the beta to an even bigger cock-of-the-walk. Be that as it may, Ken Williams — this man’s man who had the chutzpah to imagine becoming a transformative mogul of mass media, a Walt Disney-like figure — could be weirdly quick to fall under the sway of other men who seemed to embody the same qualities he cherished in himself. Sometimes that worked out okay, as when he met the furloughed police officer Jim Walls through his hairdresser and asked that man who knew nothing of computers or the games they played to join Sierra as a game designer. The three Police Quest games that resulted were… well, it’s hard to really call them good in any fundamental sense, but they were good enough for the times, whilst being fresh and unique in their subject matter when compared with all those other adventure games about dragons and spaceships. At other junctures, however, Williams’s gut instinct led him badly astray, as when he asked the police brutalist Daryl F. Gates to replace Walls as the personality behind Police Quest, a decision which appalled and outraged most of his own employees and left a stain on Sierra’s legacy that can never be fully expunged.

Just as the aforementioned two men walked and talked the part of the hard-edged, no-nonsense cop in a way that profoundly impressed Ken Williams, Walter Forbes was the very picture of the suave and sophisticated financier, making monumental deals next to a crackling fire in his elegant parlor, a glass of Chianti in hand, before rushing off to Europe in his private jet to take in an opera. For Ken, a working-class striver without any university degree to his name, much less one from Harvard, the idea that a man like this would be so interested in him and his company must have been a very alluring one indeed.

Had Ken Williams followed the advice of Jerry Bowerman and dug a little deeper into Walter Forbes and CUC, he might have learned some things to give him pause. He might have discovered, for example, that Forbes hadn’t founded CUC himself to pursue his grand vision of e-commerce, as the interview in Wired implies; he had rather bought himself a seat on an existing company’s board with a cash investment from his familial store of same, then fomented from that perch a revolt that led to the real founder being defenestrated and Forbes himself taking his place. If nothing else, this did cast Forbes’s willingness to join Sierra’s board and his early chat with Roberta Williams on the subject of an acquisition, as if he was nosing around for a weak link, in rather a different light.

Of course, there’s been an elephant in the room through all of the foregoing paragraphs, one which we can no longer continue to ignore. Once more to his credit, Ken Williams doesn’t fail to mention the elephant in his book: “Personally speaking, it would be a nice payday.”

Ken Williams had grown up with just one dream. It wasn’t to make great games or to revolutionize entertainment or even to become the next Walt Disney, although all of those things were eventually folded into it as the means to an end. It was to become rich — nothing more, nothing less. “Somewhere along the way, I developed an aggressive personality,” he writes of his boyhood and adolescence. “All that I could think about was becoming rich. Note that I said ‘rich,’ not ’employed’ or ‘successful.’ Amongst the few memories I have from that time is the constant thought of wanting to live a different life than the one I grew up in. I read books about business executives who owned yachts and jets, and who hung out with beautiful models in fancy mansions. I knew that was my future and I couldn’t wait to claim it.”

By most people’s standards, Ken and Roberta Williams were rich by the mid-1990s. But most of their wealth was illiquid, being bound up in their company — an arrangement which entailed duties and obligations that were becoming, for Ken at least, increasingly onerous. “It seemed like everyone associated with Sierra except me was having fun,” he says.

I just wrote that the decision to sell to Walter Forbes was the worst business decision Ken Williams ever made. Ironically, though, it was his best decision ever in terms of his private finances. For he sold Sierra when the “Siliwood” craze of which he had been the industry’s most outspoken and articulate proponent — that peculiar melding of computer games with Hollywood movies, complete with live actors and unabashedly cinematic audiovisual aesthetics — was at its absolute zenith; he sold when Phantasmagoria, the latest poster child for the trend, had just become Sierra’s best-selling game ever. The remainder of 1996 — a year which produced no more Siliwood hits on the scale of Phantasmagoria, from Sierra or anyone else — would show that there was only one way forward for “interactive movies” from here, and that way was down. They were doomed to be replaced by a very different vision of gaming’s future, emphasizing visceral action, emergent behavior, and player empowerment over the elaborate set-piece storytelling that had been Sierra’s bread and butter for so long.

Over the last few decades, signing Walter Forbes’s contract has allowed Ken and Roberta Williams to enjoy that enviable lifestyle that is the preserve of the ultra-wealthy alone, with multiple homes in multiple countries and a boat in which they have cruised around the world several times. Mind you, I don’t say that such a lifestyle was foremost on Ken Williams’s mind when he made the decision to sell; on the contrary, he had every expectation at the time of continuing to manage Sierra for the foreseeable future. I merely say — as if it needs to be said yet again! — that life is seldom black and white.

But we’ve belabored these points enough: Ken secured the preliminary approval of Sierra’s shareholders, signed on the dotted line on their behalf, sent out the press release, then secured their final approval to complete the transaction a few months later. On the face of it, it was indeed a great deal for them: they got to trade in their Sierra stock for 22 percent more shares in CUC, a far bigger, even faster-growing company.

Once all that was behind them, Walter Forbes and Ken Williams and all of their closest associates flew off to Paris in Forbes’s jet to celebrate the acquisition. Some members of the entourage were happier than others. At an expensive Parisian restaurant, Forbes ordered a $5000 bottle of wine, saying it was on him. “I [found] out after the fact, digging around in the accounting system, that he’d expensed it,” says Jerry Bowerman. “So he was just a liar. Just a very fat liar.”

Amazingly, Sierra On-Line wasn’t the only software publisher that Walter Forbes and CUC agreed to purchased during February of 1996. In a way, the other major acquisition turned out to be even more of a plum prize than this one. It was a publisher and distributor of educational software and games called Davidson and Associates. If that name fails to set any bells a-ringing, know that Davidson was itself the proud owner of Blizzard Entertainment, whose Warcraft 2, Diablo, and Starcraft, combined with its innovative Battle.net service for online multiplayer play, would make it the hottest brand in gaming over the course of the next few years, a veritable way of life for millions of (mostly) young men. CUC, this company nobody had ever heard of, was suddenly in possession of a gaming empire with few peers.

But for Ken Williams, the time to come would be filled with far less pleasant surprises than the meteoric ascent of Blizzard. After the acquisitions of Sierra and Davidson were finalized in June of 1996, it slowly and agonizingly dawned on him that he had made a terrible mistake. He learned that Walter Forbes had given the exact same promise of ultimate superiority in the new software arm of CUC to both him and Bob Davidson, the co-founder of Davidson and Associates. Forbes obviously couldn’t honor his promise to both men. Worse, it soon became clear that he favored Davidson whenever push came to shove. Davidson’s people took over most of the marketing and distribution of Sierra’s games, with Williams’s own people being sidelined or laid off. Williams chafed at his newfound beta status, and feuded bitterly if futilely with his de-facto superior. When Sierra failed to come up with another hit to rival Phantasmagoria’s sales in 1996 — a failure which further reduced his standing in the conglomerate as a whole, what with the numbers Blizzard was shifting — he blamed it on Davidson’s logistics and marketing.

Yet he did manage to do Sierra and CUC one great service that year, despite the constraints that were being laid upon him. Late in 1996, he agreed to hear a pitch from a new studio called Valve Corporation, founded by a couple of former Microsoft employees who had never made a game before and who were therefore having trouble gaining inroads with the other major publishers. With his background in adventure games, Williams was intrigued by Valve’s proposal for Half-Life, a first-person shooter which, so he was told, would place an unusual emphasis on its story. Even when setting that element of the equation aside, Williams knew all too well that Sierra really, really needed to become a player in the shooter space if it was to survive the popping of the Siliwood bubble. Listening to his gut, he signed Valve to a publishing contract. Well after he left Sierra, Half-Life would become by most metrics the most successful single shooter in history, by a literal order of magnitude the best-selling game that Ken Williams was ever involved with. The landscape of gaming might look vastly different today had he not made that deal; Steam, for instance, was able to come to be only thanks to Half-Life’s publication and success. Not all of Ken Williams’s gut decisions were bad ones. Far from it.

Half-Life aside, though, life under the new regime had little to offer him beyond constraints and warning signs. One of the other perks he had been promised, and that in this case was delivered, was a seat on CUC’s board. His first board meeting only reinforced his sense of the cloud of obscurity hanging around CUC’s operations. He realized that he wasn’t the only person sitting at the table who didn’t entirely understand what the company they were all supposed to be overseeing actually did. The other board members, however, didn’t much seem to care. As long as the stock price kept climbing, they were happy to leave it all in the evidently capable hands of Walter Forbes. Ken Williams:

By the end of the first hour, we had covered everyone’s golf scores and favorite wines. I was not a golfer and was left out of the discussion. I avoided the game, and was disappointed that these pillars of the business world thought it was important enough to disrupt a board meeting. We finally sat at the table, and vacations were discussed. Walter was asked at some point, “How’s business?” He answered that all was good, followed by hardly anything more. I was waiting patiently for the lights to dim and the projector to light up. It never happened. Instead we were back to conversations having nothing to do with CUC. And then the meeting ended.

Feeling out of place among the old-money scions gathered around tables such as this one, tired of having his decisions in the software space countermanded by Bob Davidson, Williams started casting about for someplace else within CUC where he could rule the roost as he had once done at Sierra. He dove deep into another recently acquired company, the e-commerce facilitator NetMarket, which had scored a prominent write-up in The New York Times two years earlier for enabling the first encrypted credit-card transaction — for a Sting CD — ever to take place on the Internet. Yet he was never quite sure of his ground there, and never felt that NetMarket was much of a priority for Forbes — a strange thing in itself, given the way the latter was always rattling on about e-commerce in interviews. Williams had become an executive without a clear role or any clearly delineated scope of authority. It was not a comfortable situation for a man of his personality and predilections.

It might therefore have seemed like good news when Bob Davidson abruptly quit in January of 1997. And yet the circumstances of his resignation were just odd enough that it was hard for even his primary internal rival to feel too sanguine about it. Davidson had had a dream job, running a software empire that had just shipped Blizzard’s Diablo to a rapturous reception. Why had he thrown it away? Williams heard through the grapevine that Davidson had come to Forbes with an ultimatum, demanding that the software arm be spun out from the CUC mother ship to become its own company as the condition of his staying on there. Why had he been so strident about this? Had he discovered something that other people hadn’t? It was almost as if he felt he had to protect the software business from whatever was coming for the rest of the company.

As it happened, Williams was never offered Davidson’s job anyway. It was given instead to one Chris McLeod, a “member of the office of the president and executive vice-president” of CUC with no background in technology, software, or gaming, although he did sport a rather impressive golf handicap.

In May of 1997, Walter Forbes announced his latest deal. CUC was to merge with another company that nobody other than Wall Street investment bankers had ever heard of, one that went by another anonymous-sounding three-letter acronym. But it turned out that HFS (“Hospitality Franchise Systems”) owned a considerable number of brands that actually were household names: Avis Rental Cars, the real-estate chains Century 21, ERA, and Coldwell Banker, and the hotel chains Days Inn, Ramada, Super 8, Howard Johnson’s, and Travelodge. The New York Times diplomatically described CUC, by contrast, as “a powerful but less known force in telemarketing, home-shopping clubs, and travel information.” HFS was far too big for CUC to gobble up like it had Sierra On-Line and Davidson and Associates. This was to be a “merger of equals.”

HFS had been founded in 1990 by an infamously ruthless, hard-charging Wall Street money man named Henry Silverman, who had grown tired of playing “second banana” to the moguls and investors he stood in between. His business plan was deceptively simple: HFS bought brands, then rented them out to others under the franchising model. Said model allowed the company to accrue most of the benefits of running a chain of real-estate firms or rental-car offices or hotels without getting bogged down in most of the responsibilities. Anyone who wished to open a branch of one of these businesses could apply to HFS for a license to use one of its brands. If approved, they would pay a lump sum up-front, followed by ongoing “subscription” fees. In return for their money, they would receive, in addition to the brand itself, guidance on best practices and access to proprietary computer systems. On the stick side of the ledger, they would also need to pass regular inspections, to assure that they didn’t dilute the cachet of the brand they leased. It would be an overstatement to claim that administering such a franchising system was trivial for HFS, but it was much less financially and logistically fraught than actually owning and running thousands of properties all over the country. The Wall Street portfolio managers who had so recently been Silverman’s colleagues ate it up. And why shouldn’t they? An investor who got in on the ground floor with HFS in 1992, when it first went public, would have gotten her money back twenty-fold by the time of the merger with CUC.

HFS was a larger company than CUC in 1997, with a more transparent and more obviously sustainable business model. Although both stock prices were overvalued by any objective measure, sporting fairly outrageous price-to-earnings ratios, you could go out into Main Street, USA, and see the sources of HFS’s revenues right there in bricks and mortar. This was not true of CUC.

Given this reality, those who knew Henry Silverman well would continue to ask themselves for years to come why he had wanted to make this deal in the first place, and why he had failed to look harder into CUC’s business before consummating it. For Silverman, unlike Ken Williams, was not in the habit of letting the gravitational pull of charm, power, and ostentatious displays of wealth trump sober-minded judgment. On the contrary, Silverman was a numbers guy to the core, a classic cold fish who seemed immune to personal charisma when he considered his potential business partners. And yet he allowed Walter Forbes to reel him in almost as easily as Ken Williams had. The player got played: “A master deal-maker bought a pig in a poke,” as Fortune magazine would be writing in the not-too-distant future.

Still, the terms of this deal quite clearly left Silverman rather than Forbes in the catbird seat. The merger agreement stipulated that Silverman would be the CEO of the conjoined venture and Forbes only the chairman of the board until January 1, 2000, after which date the two would swap roles. They would then continue to trade places, in two-year cycles, for as long as they both wanted to keep at it. That said, many of those who knew Henry Silverman best suspected that he never intended to relinquish the position of CEO, that he would find some way to freeze Forbes out when the time came to trade places. In the end, though — and as we’ll see in my next article — other developments would make all of that a moot point. In the meanwhile, Wall Street was all-in; one investment analyst said that it would take “mismanagement for this deal not to work.” She had no idea what a soothsayer she was…

Any merger as big as this one, valued at $14 billion, takes some time to effectuate. It wouldn’t go through until the very end of 1997, by which point Ken Williams would be gone from CUC and from Sierra.

In August of 1997 — “one miserable year after Sierra’s acquisition had been completed,” as he puts it — Williams decided that he had had enough. A proud man, he felt disrespected, even “humiliated,” at that month’s board meeting, where his proposals and all of his attempts to steer the conversation around to actual matters of business had not gone down well. As soon as the meeting adjourned, he sat down at the computer in his office and typed out a letter of resignation. Walter Forbes, this fellow whom Williams had once thought he shared a special bond with as a fellow dynamic man of business, accepted the letter without much comment or expression of regret. It took some time to finalize Williams’s departure with Human Resources, but it was agreed in the end that his last day would be November 1.

So, Ken Williams’s association with Sierra On-Line, the company he had founded and built from the ground up over almost eighteen years, officially ended on November 1, 1997. There was no public or private fanfare — no going-away party, no line of colleagues awaiting a last handshake. Nothing like that. “I just packed my stuff and went home,” he says. Both coincidentally and not so coincidentally, Mike Brochu and Jerry Bowerman, Williams’s right-hand men who had argued so fruitlessly against the acquisition, likewise decided they had had enough at around the same time. This left Sierra as little more than another of Henry Silverman’s brands, in the hands of people who had bought their way into it rather than growing it from the grass roots. They would deign to fund and release a few more games that played in the old Sierra’s worlds, would even employ a few of the old designers to make them. Nevertheless, one can make a compelling argument that the main story of the Sierra that is still so fondly remembered by adventure-game fans today ended on that November 1, 1997, when Ken Williams walked out of his office for the last time, with no one even bothering to tell him goodbye. What followed — and will follow, in the next two articles of this series — was merely the epilogue, or perhaps the hangover; you can pick your own metaphor.

It beggars belief that something so huge — something that touched the lives of so many people who worked for Sierra or played the many, many games of its golden years — could end so anticlimactically, with one unremarkable-looking 43-year-old office worker quietly switching off his computer and driving home. But such is life in the real world. Concluding whimpers are more common than bangs.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line by Ken Williams, Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports by Howard Schilit, Stay Awhile and Listen, Book II: Heaven, Hell, and Secret Cow Levels by David L. Craddock, and Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay. Wired of November 1997; Los Angeles Times of February 21 1996; New York Times of August 12 1994 and May 27 1997; Wall Street Journal of July 29 1998; Fortune of November 1998.

I owe a big debt to Duncan Fyfe, whose 2020 article on this subject for Vice is a goldmine of direct quotations and inside information. I also made use of CUC’s last annual report before the merger with HFS, and of the materials held in the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play.

Zack

April 4, 2025 at 5:04 pm

I have to ask, but when you say this “to the real founder being defenestrated”, do you mean this in the literal sense, or just as a turn of phrase for the founder being ousted ? Not that it’s any less grim either way…

Learning more about Sierra is always fascinating. I’ve only ever known them as the name on the Impression Games boxes, Pharaoh, Zeus, Emperor… this blog really has taught me much about them.

arcanetrivia

April 4, 2025 at 7:09 pm

I highly doubt it’s literal, but I look forward to the thrilling tale of being proved wrong in this assumption… :)

Jimmy Maher

April 4, 2025 at 7:18 pm

That’s a word I picked up from reading too much of The Economist, I think. They tend to favor it. I find it oddly delightful, what with the German root being so obvious. It’s not meant literally, no. ;)

Sniffnoy

April 4, 2025 at 7:26 pm

That’s actually a Latin root — German gets “Fenster” also from Latin (although there the borrowing is older). Meanwhile Latin may have borrowed it from Etruscan, but there the trail goes cold.

Mike Russo

April 4, 2025 at 11:29 pm

Yeah, it’s a clear Latin derivation, though it only comes into popular English usage following the Defenestration of Prague. Though one of my favorite bits of historical trivia is that the Defenestration of Prague that most* people** know about was actually the third*** Defenestration of Prague! Those Czechs and their windows.

* some

** nerds

*** or maybe actually the second, the one in 1483 was kinda lame by comparison with the earlier and later defenestrations.

PlayHistory

April 4, 2025 at 5:21 pm

Thank you for taking Ken to task over his narrative of events. Ever since I learned about this story, I felt there were contradictions which were not resolved by what he’s said in the past – even before the memoir.

I think video game fans want to believe Ken’s innocence in all this, unable to divorce themselves from a dualistic view of the “noble and pure” executive archetype and the “despicable, baby killing” CEO. Ken wasn’t (isn’t) a bad person for his failings: He was wrapped up in the throes of money and success. If he had stayed in the industry, I think he would have made more smart decisions and continued to be respected. I think you strike it right though – his fundamental mission was not changing the world. That’s fine, but he didn’t really seem to care who he left in a lurch.

I hope Roberta’s getting her due as well. There’s obviously more than one reason that Sierra was dismantled, but if they had been putting out stuff on the calibre of Diablo and Starcraft, maybe it wouldn’t have been as brutal…

Alex Smith

April 4, 2025 at 5:48 pm

Great article Jimmy that breaks down a complicated mess quite cogently. While we can never truly know the heart of a person, I feel like your analysis of Ken Williams’ motivations seems pretty spot on from what we know of the man.

One tiny nitpick: Bob Davidson should be referred to as the cofounder of Davidson and Associates since he started the business with his wife, Jan.

Jimmy Maher

April 4, 2025 at 7:24 pm

Thanks!

JB Schirtzinger

April 4, 2025 at 8:45 pm

Some people, and the influence they hold, are only felt in their absence.

Casey Nordell

April 4, 2025 at 11:01 pm

I really enjoyed this and look forward to the rest. I bought Ken’s book, but I’ve held off on reading it because I wanted to read your account of events first.

The end of Infocom was when I was exiting my tween years. And the end of Sierra and Origin was when I was exiting my teen years.

These were big events in my life, institutions coming to their endings which I couldn’t possibly comprehend at the time. I will always miss the characters, worlds, and stories that they brought us. And now I finally get to see how all three fell apart through the lens of time passed, the wisdom of older age, and of course the high quality of your research and writing.

Jogy

April 5, 2025 at 2:29 am

> He might have discovered, for example, that Forbes hadn’t founded CUC himself to pursue his grand vision of e-commerce, as the interview in Wired implies; he had rather bought himself a seat on an existing company’s board with a cash investment from his familial store of same, then fomented from that perch a revolt that led to the real founder being defenestrated and Forbes himself taking his place.

Hmm, whom does this remind me of … ?

Fascinating story, as usual!