From the 1980s until well into the 1990s, the CRPG genre was typically dumped into the same broad bucket as the adventure game by the gaming press. Indeed, as late as the turn of the millennium, Computer Gaming World magazine had an “Adventure/RPG” department, complete with regular columnists whose beat encompassed both genres. Looking back, this lack of distinction might strike us as odd: CRPGs, which are to a greater or lesser extent simulations of an imaginary world with a considerable degree of emergent behavior, are far more procedurally intensive than traditional adventure games and provide a very different experience.

Back in the day, however, no one blinked an eye. For the one thing the genres did plainly have in common was sufficient to set them apart from all other sorts of games: their engagement with narrative. Whatever else they might happen to be, both an adventure game and a CRPG were a story that you engaged with much as you might a book — that is to say, you played through it once to completion, then set it aside. Contrast this with other kinds of games, which provided shorter-form experiences that you could repeat again and again.

As you are well aware if you’ve been reading my more recent articles, the adventure game suffered its own commercial slump in the 1990s. Said slump began a couple of years after the CRPG slid into the doldrums, but it proved vastly more sustained — so sustained, in fact, that the genre has been more or less consigned to niche status ever since. It’s frequently been argued that the adventure game didn’t so much die on the vine as get eaten alive by other gaming genres. Already at the very dawn of the 1990s, games like Wing Commander started to appropriate the adventure’s interest in telling a relatively complex story and to insert it into new gameplay contexts. That left set-piece puzzle-solving as the adventure’s only remaining unique attribute, and it soon turned out that most people had never been all that keen on that gameplay paradigm in the first place. Of course, this is a hopeless oversimplification of the adventure genre’s fall from grace — bad design and a more generalized drift toward more action-oriented forms of gameplay surely played major roles as well — but that doesn’t mean there isn’t something to the argument.

I bring all of this up here because I think that we can see a variation of the Wing Commander syndrome afflicting the CRPG as well during its own years in the wilderness. That is to say that, even as the profile of games that explicitly called themselves CRPGs was waning during the mid-1990s, games of other types were starting to betray the genre’s unmistakable influence, via the rise of what we’ve come to call “RPG elements.” We see these especially in the strategy games of the era.

In MicroProse’s 1994 classic XCOM,[1]The game was known as UFO: Enemy Unknown in its British homeland and elsewhere in Europe. you guide squads of soldiers who each have their own distinctive strengths, weaknesses, and personality traits, who can “level up” and improve their skills and equipment as they fight battles against alien invaders. Many players have described the tight bond they form with their soldiers as being at the heart of their love for the game as a whole, described feeling real bereavement and even guilt when one of their stalwart veterans gets killed in action after following their orders.

The same year as XCOM, SSI celebrated their impending loss of the Dungeons & Dragons license by releasing Panzer General, a “beer and pretzels” wargame which casts you in the role of a Wehrmacht general during the Second World War, passing through campaigns and battles drawn from real and alternate history, bringing your most loyal units along with you and watching proudly as they too grow in effectiveness — and perhaps crying when your well-intentioned orders get them blown to Kingdom Come.

These trends have persisted down to today, when RPG elements are found in such far-flung genres as sports games that let you guide an athlete through a “career mode” and language-learning apps that deal in experience points and “daily quests.” The point of contrast between the adventure and CRPG genres in all of this lies in the fact that the latter has fully returned from its brush with death and retaken its old place as a recognized part of the mainstream gaming landscape. In the heyday of XCOM and Panzer General, however, it was by no means obvious that the CRPG was not destined to be looted for whatever ideas other genres found of use and then left high and dry, just as the adventure would shortly be.

If we’re looking for a poster child for the trend, it would be hard to find a better one than New World Computing, a studio and publisher that was located not that far from Interplay in Southern California. New World’s equivalent of Brian Fargo was one Jon Van Caneghem, who built his company on the back of a CRPG franchise known as Might and Magic, producing five installments of same between 1986 and 1993. Might and Magic’s commercial fortunes paralleled those of the genre writ large. Plotted on a grid, they would yield an almost perfectly symmetrical bell curve, rising to a peak with Might and Magic III in 1991 and then declining markedly again with the next two games.

By 1994, then, Van Caneghem had to face up to the reality that it might be time to take a break from the genre that had gotten New World this far. So, instead of jumping right into a Might and Magic VI, he came up with a simple fantasy strategy game that used CRPG-style character-building as its special sauce. Hoping to capitalize on the residual goodwill toward New World’s flagship series, he called it Heroes of Might and Magic, even though it had nothing to do with those games in terms of either its gameplay or its fiction, beyond their mutual use of the broadest archetypes of epic fantasy. In all honesty, the choice of a name for the new game probably didn’t make that much difference one way or the other. What did matter was that Heroes served up tons of accessible fun, being one of those rare gaming specimens that is equally appealing to both the hardcore and the more casual crowd. Upon its release in late 1995, it sold better than any of the CRPGs of which it had been positioned as a spinoff. Understandably enough under the circumstances, Van Caneghem and company left the mother series on the shelf for a while longer, concentrating instead on getting a Heroes of Might and Magic II ready to go in time for the following Christmas. Some might have called this another sign of the CRPG’s declining fortunes; Van Caneghem just called it a smart business decision.

In still another sign of the changing times in gaming, Van Caneghem began looking for a buyer for New World in early 1996, waving the success of Heroes around as his banner while he did so. The decision to surrender his independence wasn’t an easy one, but he felt compelled to make it nevertheless. As the gaming marketplace continued to expand in scope and revenues, it was getting harder and harder for boutique publishers like New World to secure space for themselves on the shelves of big-box retailers. They had managed to score a hit despite the headwinds with Heroes I, but Van Caneghem knew that he would need to harness his games to a bigger engine if he wanted the good times to keep on rolling. On July 10, 1996, New World was acquired by The 3DO Company, just in time for the latter to place the forthcoming Heroes II in more stores than ever that Christmas.

3DO had been spun out of Electronic Arts five years earlier, with EA’s own iconoclastic founder Trip Hawkins at its head. His vision at the time was to build a different kind of games console — different in at least two ways from Nintendo and Sega, who dominated that space during the first half of the 1990s. Rather than being a single chunk of hardware that was manufactured and sold from a single source, the 3DO console was to be a set of specifications that any hardware maker could license. On a similarly empowering note, 3DO would treat those who wished to make software for the platform like partners rather than hostages or supplicants, charging them significantly lower fees than Nintendo or Sega and encouraging more diverse content. Speaking of which: the 3DO was envisioned as much as a multimedia set-top box for the living room as it was a conventional games console. In addition to games, you’d be able to buy interactive encyclopedias, interactive road atlases, interactive documentaries. Even when it came to entertainment, “interactive movies” starring real actors would ideally predominate over the likes of Super Mario. All of this was expected to drive the age of the average 3DO user dramatically upward; it was to be the first console made for and widely adopted by adults.

Alas, none of it panned out as Trip Hawkins had hoped, for a variety of reasons. When the first units finally began to arrive in stores in late 1993, they were expensive in comparison to the competition from Nintendo and Sega. The consoles never gathered the halo of prestige that might have made their higher price survivable; despite Hawkins’s best efforts to talk up the multimedia revolution, most of the adults he had hoped to reach persisted in seeing the 3DO box as just another games console for the kiddies. When judged by this standard, the interactive movies and other highfalutin titles it boasted didn’t make it very appealing.

Thus the 3DO consoles were already under-performing expectations in late 1995, when Sony came along with the PlayStation. Sony did some of what Hawkins had tried to do, fostering a better relationship with developers and offering content that could appeal to a slightly older demographic than that of Nintendo and Sega. Yet they did it in a more judicious way, without completely abandoning the walled-garden approach that had dominated in the console space since the mid-1980s and without venturing too far afield from videogames as they were conventionally understood. Most importantly, they combined their blended approach with better hardware than 3DO had to offer, sold at a far cheaper price. 3DO’s attempt to remake the living-room console as a more open and diverse platform had been a noble experiment in its way, but after the PlayStation hit the scene it became abundantly clear that it had failed.

This failure left The 3DO Company with no obvious reason to exist. Yet the rump of Trip Hawkin’s original grand vision was still fairly flush with venture capital, and nobody there was prepared to just turn out the lights and go home. With his revolutionary agenda having failed him, Hawkins decided to pivot into conventional game publishing — in effect, to return to the business model of Electronic Arts, the very company he had walked away from to found 3DO. But much to his disappointment, he couldn’t make lightning strike twice in this way either; suffice to say that 3DO’s early software portfolio was nothing like the list of early games from EA, which included such future icons of the medium as M.U.L.E., Archon, Murder on the Zinderneuf, and Pinball Construction Set. The one clear exception to a general rule of derivative also-rans from 3DO was Meridian 59, a graphical MMORPG which beat the more celebrated Ultima Online to market by a year, only to be left to slowly die of neglect.

Against such underwhelming competition, the acquisition of New World stands out all the more as the wisest move ever made by 3DO as a publisher. For this deal would yield almost all of the other games to appear with the 3DO logo that have a legitimate claim to being remembered today.

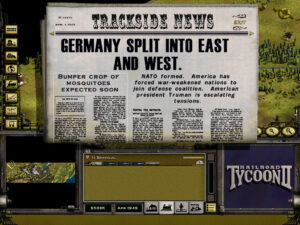

In the beginning, the deal seemed equally beneficial to New World. Jon Van Caneghem was thrilled to be able to turn most of the details of finance and logistics over to 3DO and concentrate on the reason he had founded his company in the first place: to make great games. “I think we started to do our best work after I sold the company to 3DO,” he says, “because I could focus 100 percent on the game development.” The partnership hit the ground running with Heroes of Might and Magic II, which not only refined and expanded upon the gameplay template of its predecessor but added a slew of cutscenes and other audiovisual bells and whistles that were made possible only by the sudden injection of 3DO’s cash. Buoyed by the latter’s extensive distribution network, a happy outcome of ties to Electronic Arts that had still not been completely severed, Heroes II became an even bigger hit than the original.

3DO’s money made it possible for New World to take on multiple high-profile projects at one time. Thus before Heroes II was even released, Van Caneghem had already set some of his staff to work on Might and Magic VI: The Mandate of Heaven, his return to the core series of CRPGs. This might have seemed a risky decision on the face of it, given the current moribund state of the CRPG genre, but the relationship between Van Caneghem and 3DO was strong enough that his new bosses were willing to trust his instincts. Just as 1996 expired, those instincts seemed to be at least partially vindicated, when Blizzard’s Diablo appeared and promptly blew up to massive popularity.

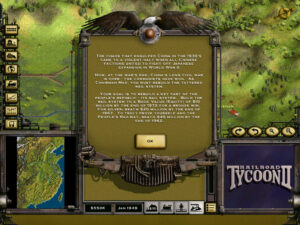

Might and Magic VI has nothing to do with the history of imperial China. The phrase “Mandate of Heaven” is used as its subtitle just because someone at New World thought it sounded cool. Pretty much everything else to be found in the game has the same justification.

Indeed, of all the games and series I’ll be discussing in these articles, the Might and Magic series was in some ways the closest in spirit to Diablo. This isn’t to say that the two were peas in a pod: just to begin the list of differences, those first five Might and Magic games were all turn-based rather than real-time, first-person rather than third-person, with hand-crafted rather than procedurally-generated dungeons and with far more complex and demanding systems to master, whilst quite possibly requiring an order of magnitude more hours for the average player to finish a single time. For all that, though, they did share with Diablo a strident ethic of fun as the final adjudicator. They had no interest in elaborate world-building or statement-making in the way of, say, the Ultima series. At heart, a Might and Magic game was a giant toy box, overflowing with challenges and affordances that could be engaged with in a nearly endless number of ways. Although a Might and Magic CRPG might not represent much of an argument for games as refined storytelling vehicles, much less as art, you were generally too busy messing with all the stuff you found inside it to care.

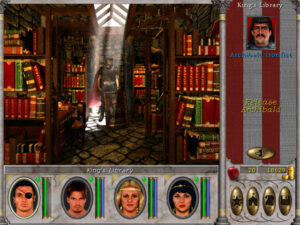

Do you remember me telling you that Fallout raised the bar of sophistication in CRPG aesthetics? You won’t catch me saying that today. Might and Magic VI’s aesthetic principles are pure, unadulterated teenage Dungeon Master.

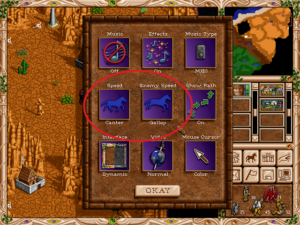

Being himself not a particularly artsy guy, Jon Van Caneghem saw no reason to alter this philosophy for Might and Magic VI. Still, he was keenly aware that some things would have to change if the new game was to fit comfortably into a post-DOOM, post-Quake world. Like its predecessors, Might and Magic VI would be a first-person “blobber”: an entire party of characters under your control would be “blobbed” together into a sort of lethal octopus, with you the player staring out from the center of the writhing mass. The big difference with the sixth installment would be that the amalgamation would move about freely — i.e., DOOM (or Ultima Underworld) style — rather than over a step-wise grid of possible locations on the map.

That said, the engine used for Might and Magic VI was not anything to leave shooter fans of its era overly impressed. New World decided not to require or even support the new breed of 3D-graphics cards that were taking gaming by storm just as work on it was beginning. In retrospect, this decision was perhaps a questionable one. For it left Might and Magic VI’s visuals lagging miles behind the state of the art by the time of its eventual release in the spring of 1998; comparisons with Unreal, the latest shooter wunderkind on the block, did not redound to its benefit.

This is not to say that the graphics aren’t endearing. A willingness to be goofy was always intrinsic to the series’s personality. The pixelated environments and the monsters that sometimes look like cut-out dolls that have been pasted on top of a picture of their surroundings are part and parcel of that. If it looked more refined, it wouldn’t look like Might and Magic.

Was anything ever more late 1990s than these digitized character portraits? Xena: Warrior Princess called, asking for Lucy Lawless back.

As I mentioned when discussing Fallout, one of the hidden stumbling blocks for those who dreamed of resuscitating the CRPG was reconciling free-scrolling, real-time movement with the genre’s tradition of relatively complex, usually turn-based combat. I found Fallout’s approach more frustrating than satisfying; I’m therefore happy to say that I like what Might and Magic VI does much better. As with Fallout, there is a turn-based mode here that the game can slip in and out of. But there are two key differences. One is that you choose when to enter and exit the turn-based mode, by hitting — appropriately enough — the enter key. The other is that you can also fight in real-time mode if you like. In a lot of situations, doing so tends to get you killed in a hurry, but there are places, especially once you’ve built up your characters a bit, where you can run and gun almost as if you’re playing a first-person shooter. In turn-based mode, on the other hand, the game plays much like the Might and Magics of yore, except that your party is frozen in place; adjusting your position requires a quick trip in and out of real-time mode. It may sound a little wonky, but it all hangs together surprisingly well in practice. I find Might and Magic VI’s combat to be good fun, which is more than I can say for Fallout.

And it’s fortunate that I feel that way, because fighting monsters, preparing to fight monsters, and traveling to where monsters are waiting to be fought are what you spend most of your time doing. Might and Magic VI has none of Fallout’s ambitions to reinvent the CRPG as a more holistic sort of interactive narrative. It gives you a collection of blatantly artificial stage sets rather than a lived-in world, filled with non-player characters who function strictly as antagonists to slay, as irrelevant blank slates, or as quest-giving slot machines. Sure, there’s a story — in fact, a story that follows directly on from the main campaign in Heroes of Might and Magic II, representing an effort to integrate the two series in some other sense than their names, their bright and colorful visual aesthetics, and their epic-fantasy trappings. Evil forces are about to destroy the world of Enroth, and Archibald, the villain from Heroes II, is mixed up with them, but not in the way that you might think, and… You know what? I really can’t remember, even though I didn’t finish the game all that long ago. No, wait… I do remember that aliens turn out to be behind it all. This gives you the opportunity to run around shooting robots with lasers before all is said and done. As I mentioned, Might and Magic VI is never afraid to be goofy.

It’s weirdly freeing to play a game that so plainly answers only to the dictates of fun. Might and Magic VI is a monument to excess sufficient to make a Saudi prince blanch. Whenever I think about it, I remember Gary Gygax’s stern admonition against just this sort of thing in the first-edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide, that staple work of literature of my generation’s nerdy youth.

Many campaigns are little more than a joke, something that better Dungeon Masters jape at and ridicule — rightly so on the surface — because of the foolishness of player characters with astronomically high levels of experience and no real playing skill. These godlike characters boast and strut about with retinues of ultra-powerful servants and scores of mighty magic items, artifacts, [and] relics adorning them as if they were Christmas trees decked out with tinsel and ornaments. Not only are such “Monty Haul” games a crashing bore for most participants, they are a headache for their Dungeon Masters as well…

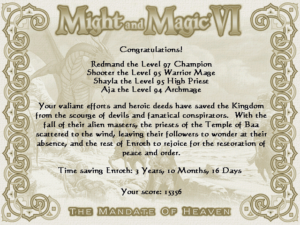

Might and Magic VI is the perfect riposte for old Gary’s po-faced pronouncements. It lets you advance your characters to level 90 and beyond, by which time they pretty much are gods, able to teleport instantly from one side of a continent to the other and to cover shorter distances by flying high above the mountaintops, raining fiery death from the heavens upon any poor earthbound creatures who happen to be visible below. And you know what? It’s not boring at all. It’s actually kind of awesome. Like Diablo, Might and Magic VI zeroes in relentlessly on the lizard-brain appeal of its genre. We all like to watch the numbers associated with our characters go up and then go up some more, like to know that we’re more formidable today than we were yesterday. (If only real life worked like that…)

Is this really a good idea? Ah, don’t worry about it. This isn’t the sort of game that goes in for moral dilemmas. If it feels good, do it.

The world in which this progress narrative takes place may not be terribly believable even as fantasy goes, but it’s appropriately sprawling. The lovely, throwback cloth map that came in the original box contains no fewer than fifteen discrete regions that you can visit, each of them dauntingly large, full of towns and castles and roaming creatures and hidden and not-so-hidden curiosities, among them the entrances to multiple dungeons that are sometimes shockingly huge in themselves. Although I’m sure some of our modern DLC-fueled monstrosities have far surpassed it in size by now, Might and Magic VI might just be the biggest single CRPG that yours truly has ever played from start to finish.

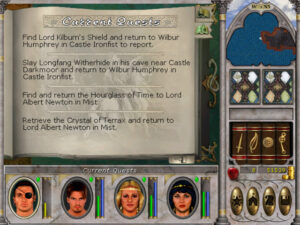

The game was able to hold my interest for the 100 hours or more I spent with it by giving me so darn much to do. Every town has at least a few quests to see through. Sometimes these are related to the main story line, but more often they’re standalone,. Each of the character classes can evolve into two more advanced incarnations of itself; an archer, for example, can become a “battle mage” and then a “warrior mage.” Doing so entails hunting down the necessary trainer and completing a quest for him or her. Your characters’ more granular skills, which encompass the expected schools of magic and types of weaponry alongside miscellaneous talents ranging from “Bodybuilding” to “Repair Item,” also require trainers in order to be advanced to “Expert” and then “Master” status. There’s always something to do, some goal to pursue, whether it’s provided by the game or one you made up for yourself: collect every single spell; pray at every shrine during the one month of the year when you get something out of it. Because there’s no complex plot whose own needs have to act as a check on your wanderings, it’s always you rather than the game who gets to decide what you do next. This world is truly your oyster — as long as you’re tough enough to take on the many and varied monsters that infest every corner of it that you enter, that is.

The toy-box quality of Might and Magic VI lets it get away with things that less sanguine, more self-serious peers would get dinged for. The jank in the engine — and make no mistake, there’s a lot of jank here — feels more like a feature than a bug when, say, you find just the right angle to stand in a doorway, the one that lets you whale away on a group of monsters while they for some reason can’t hit you. Fairly early in my play-through, I found myself in a sewer filled with living oozes that were impervious to weaponry and shot blobs of slime that were corrosive to armor. The sensible thing to do would have been to go away and come back later. Instead of being sensible, I found a stairway from whose top I could throw my one effective spell at the oozes while they were unable to hit me at all. I spent several evenings luring oozes from all over the sewer back to that killing floor, harvesting huge quantities of experience points from them. Sure, it was kind of tedious, but it was kind of great at the same time. Finding exploits like this — exploits that would undermine a less gonzo, more finely calibrated game — is just another part of the fun of Might and Magic VI. Everyone who’s ever played it seems to come away with her own list of favorite ways to break it.

I’m not even all that bothered that the game feels a little bit unfinished. As you play, you’ll probably find yourself exploring Enroth in an eastward to westward direction, which is all too clearly also the direction in which New World built their world. The last couple of regions you’re likely to visit, along the western edge of the map, are deserts filled with hordes of deadly dragons and not much else. It’s plain as day that New World was running out of gas by the time they got this far. But, in light of all they had already put into their world by this point, it’s hard to begrudge them the threadbare westerly regions too much. I’m well aware that I’m not usually so kind toward such failures to stick the landing; this is the place where I usually start muttering about the need for a work to be complete in an “Aristotelian sense” and all the rest. Never fear; we’ll doubtless return to such pretensions in future articles. But in the case of a joyously goofy, loosey-goosey epic like Might and Magic VI… well, how much more of it do you really want? It’s just not a game to which Aristotelian symmetries apply.

The game is old-school more in spirit than in execution. Among its welcome conveniences is a quest log that’s more reliably to-the-point than the one found in Fallout or even the later Baldur’s Gate. Its interface too is clean and easy to come to grips with, even today. Again, the same can’t be said of Fallout…

Might and Magic VI was released on April 30, 1998. This places it at almost the exact midpoint between Fallout, that first exemplar of a new breed of CRPGs in the offing, and the CRPGS that Interplay would publish near the end of 1998, which would serve to cement and consolidate Fallout’s innovations. For its part, Might and Magic VI can be seen as a bridge between the old ways and the new. In spirit, it’s defiantly old-school. Yet there are enough new features and conveniences — including not just the free-scrolling movement and optional real-time combat, but also such niceties as a quest log, a superb auto-map, and a raft of other information-management functions — to mark it out as a product of 1998 rather than 1988 or even 1993. It sold 125,000 copies in the United States alone, enough to justify Jon Van Caneghem’s risky decision to take a chance on it in the midst of the driest period of the CRPG drought. And its success was well deserved. Few latter-day installments of any series have done as good a job of ratcheting up their accessibility whilst retaining the essence of what made their predecessors popular.

For all their vast differences in form and spirit, aesthetics and gameplay, Diablo, Fallout, and Might and Magic VI together left gamers more excited about the CRPG genre in general than they had been in years. Interplay was now preparing to seize that opportunity. Ten years after the much-celebrated Pool of Radiance, Brian Fargo and company, working in concert with a card-game publisher called Wizards of the Coast, were preparing Dungeons & Dragons for a brand-new star turn. The first mover of the RPG was about to get its mojo back.

I played Might and Magic VI for 100 hours, and all I got was this lousy certificate. Am I proud of my achievement? Maybe just a little…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play by Morgan Ramsay and Advanced D&D: Dungeon Master’s Guide by Gary Gygax. Computer Gaming World of October 1997, June 1998, August 1998, and April 2004; Retro Gamer 49; XRDS: The ACM Magazine for Students of Summer 2017.

Online sources include Matt Barton’s interview with Jon Van Caneghem, the RPG Codex interview with Jon Van Caneghem, the Arcade Attack interview with Trip Hawkins, and “Trip’s Big Interactive Reset” by Ernie Smith at Tedium.

Where to Get It: The first six Might and Magic CRPGs are available as a single digital purchase from GOG.com. What a deal!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The game was known as UFO: Enemy Unknown in its British homeland and elsewhere in Europe. |

|---|