My one big regret was the PlayStation version [of Broken Sword]. No one thought it would sell, so we kept it like the PC version. In hindsight, I think if we had introduced direct control in this game, it would have been enormous.

— Charles Cecil of Revolution Software, speaking from the Department of Be Careful What You Wish For

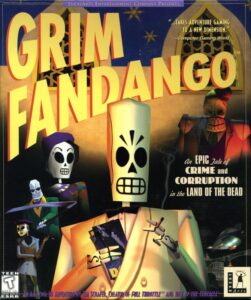

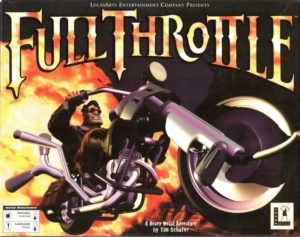

One day in June of 1995, Tim Schafer came to work at LucasArts and realized that, for the first time in a long time, he didn’t have anything pressing to do. Full Throttle, his biker movie of an adventure game, had been released several weeks before. Now, all of the initial crush of interviews and marketing logistics was behind him. A mountain had been climbed. So, as game designers do, he started to think about what his next Everest should be.

Schafer has told in some detail how he came up with the core ideas behind Grim Fandango over the course of that summer of 1995.

The truth is, I had part of the Fandango idea before I did Full Throttle. I wanted to do a game that would feature those little papier-mâché folk-art skeletons from Mexico. I was looking at their simple shapes and how the bones were just painted on the outside, and I thought, “Texture maps! 3D! The bones will be on the outside! It’ll look cool!”

But then I was stuck. I had these skeletons walking around the Land of the Dead. So what? What did they do? Where were they going? What did they want? Who’s the main character? Who’s the villain? The mythology said that the dead walk the dark plane of the underworld known as Mictlān for four years, after which their souls arrive at the ninth plane, the land of eternal rest. Sounds pretty “questy” to me. There you have it: a game.

“Not cool enough,” said Peter Tscale, my lead artist. “A guy walking in a supernatural world? What’s he doing? Supernatural things? It just sounds boring to me.”

So, I revamped the story. Adventure games are all fantasies really, so I had to ask myself, “Who would people want to be in a game? What would people want to do?” And in the Land of the Dead, who would people rather be than Death himself? Being the Grim Reaper is just as cool as being a biker, I decided. And what does the Grim Reaper do? He picks up people who have died and carts them over from the other world. Just like a driver of a taxi or limo.

Okay, so that’s Manny Calavera, our main character. But who’s the bad guy? What’s the plot? I had just seen Chinatown, and I really liked the whole water-supply/real-estate scam that Noah Cross had going there, so of course I tried to rip that off and have Manny be a real-estate salesman who got caught up in a real-estate scandal. Then he was just like the guys in Glengarry Glen Ross, always looking for the good leads. But why would Hector Lemans, my villain, want real estate? Why would anyone? They’re dead! They’re only souls. What do souls in the Land of the Dead want?

They want to get out! They want safe passage out, just like in Casablanca! The Land of the Dead is a transitory place, and everybody’s waiting around for their travel papers. So Manny is a travel agent, selling tickets on the big train out of town, and Hector’s stealing the tickets…

The missing link between Full Throttle and Grim Fandango is Manny’s chauffeur and mechanic Glottis, a literal speed demon.

This, then, became the elevator pitch for Grim Fandango. Begin with the rich folklore surrounding Mexico’s Day of the Dead, a holiday celebrated each year just after Halloween, which combines European Christian myths about death and the afterlife with the older, indigenous ones that still haunt the Aztec ruins of Teopanzolco. Then combine it with classic film noir to wind up with Raymond Chandler in a Latino afterlife. It was nothing if not a strikingly original idea for an adventure game. But there was also one more, almost equally original part of it: to do it in 3D.

To hear Tim Schafer tell the story, the move away from LucasArts’s traditional pixel art and into the realm of points, polygons, and textures was motivated by his desire to deliver a more cinematic experience. By no means does this claim lack credibility; as you can gather by reading what he wrote above, Schafer was and is a passionate film buff, who tends to resort to talking in movie titles when other forms of communication fail him. The environments in previous LucasArts adventure games — even the self-consciously cinematic Full Throttle — could be shown only from the angle the pixel artists had chosen to draw them from. In this sense, they were like a theatrical play, or a really old movie, from the time before Orson Welles emancipated his camera and let it begin to roam freely through his sets in Citizen Kane. By using 3D, Schafer could become the Orson Welles of adventure games; he would be able to deliver dramatic angles and closeups as the player’s avatar moved about, would be able to put the player in his world rather than forever forcing her to look down on it from on-high. This is the story he still tells today, and there’s no reason to believe it isn’t true enough, as far as it goes.

Nevertheless, it’s only half of the full story. The other half is a messier, less idealistic tale of process and practical economics.

Reckoned in their cost of production per hour of play time delivered, adventure games stood apart from any other genre in their industry, and not in a good way. Building games entirely out of bespoke, single-use puzzles and assets was expensive in contrast to the more process-intensive genres. As time went on and gamers demanded ever bigger, prettier adventures, in higher resolutions with more colors, this became more and more of a problem. Already in 1995, when adventure games were still selling very well, the production costs that were seemingly inherent to the genre were a cause for concern. And the following year, when the genre failed to produce a single million-plus-selling breakout hit for the first time in half a decade, they began to look like an existential threat. At that point, LucasArts’s decision to address the issue proactively in Grim Fandango by switching from pixel art to 3D suddenly seemed a very wise move indeed. For a handful of Silicon Graphics workstations running 3D-modelling software could churn out images far more quickly than an army of pixel artists, at a fraction of the cost per image. If the graphics that resulted lacked some of the quirky, hand-drawn, cartoon-like personality that had marked LucasArts’s earlier adventure games, they made up for that by virtue of their flexibility: a scene could be shown from a different angle just by changing a few parameters instead of having to redraw it from scratch. This really did raise the prospect of making the more immersive games that Tim Schafer desired. But from a bean counter’s point of view, the best thing about it was the cost savings.

And there was one more advantage as well, one that began to seem ever more important as time went on and the market for adventure games running on personal computers continued to soften. Immersive 3D was more or less the default setting of the Sony PlayStation, which had come roaring out of Japan in 1995 to seize the title of the most successful games console of the twentieth century just before the curtain fell on that epoch. In addition to its 3D hardware, the PlayStation sported a CD drive, memory cards for saving state, and a slightly older typical user than the likes of Nintendo and Sega. And yet, although a number of publishers ported their 2D computer-born adventure games to the PlayStation, they never felt entirely at home there, having been designed for a mouse rather than a game controller.[1]A mouse was available as an accessory for the PlayStation, but it was never very popular. A 3D adventure game with a controller-friendly interface might be a very different proposition. If it played its cards right, it would open the door to an installed base of customers five to ten times the size of the extant market for games on personal computers.

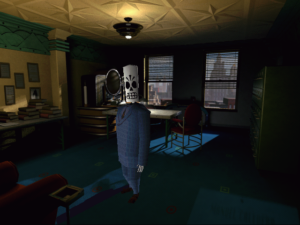

Working with 3D graphics in the late 1990s required some clever sleight of hand if they weren’t to end up looking terrible. Grim Fandango’s masterstroke was to make all of its characters — like the protagonist Manny Calavera, whom you see above — mere skeletons, whose faces are literally painted onto their skulls. (The characters are shown to speak by manipulating the texture maps that represent their faces, not by manipulating the underlying 3D models themselves.) This approach gave the game a look reminiscent of another of its cinematic inspirations, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, whilst conveniently avoiding all of the complications of trying to render pliant flesh. A win-win, as they say. Or, as Tim Schafer said: “Instead of fighting the tech limitations of 3D, you have to embrace them and turn them into a style.”

But I’m afraid I’ve gotten slightly ahead of myself. This constellation of ideas, affordances, problems, and solutions was still in a nascent form in November of 1995, when LucasArts hired a young programmer fresh out of university by the name of Bret Mogilefsky. Mogilefsky was a known quantity already, having worked at LucasArts as a tester on and off while he was earning his high-school and university diplomas. Now, he was entrusted with the far more high-profile task of making SCUMM, LucasArts’s venerable adventure engine, safe for 3D.

After struggling for a few months, he concluded that this latest paradigm shift was just too extreme for an engine that had been created on a Commodore 64 circa 1986 and ported and patched from there. He would have to tear SCUMM down so far in order to add 3D functionality that it would be easier and cleaner simply to make a new engine from scratch. He told his superiors this, and they gave him permission to do so — albeit suspecting all the while, Mogilefsky is convinced, that he would eventually realize that game engines are easier envisioned than implemented and come crawling back to SCUMM. By no means was he the first bright spark at LucasArts who thought he could reinvent the adventuring wheel.

But he did prove the first one to call his bosses’ bluff. The engine that he called GrimE (“Grim Engine,” but pronounced like the synonym for “dirt”) used a mixture of pre-rendered and real-time-rendered 3D. The sets in which Manny and his friends and enemies played out their dramas would be the former; the aforementioned actors themselves would be the latter. GrimE was a piebald beast in another sense as well: that of cheerfully appropriating whatever useful code Mogilefsky happened to find lying around the house at LucasArts, most notably from the first-person shooter Jedi Knight.

Like SCUMM before it, GrimE provided relatively non-technical designers like Tim Schafer with a high-level scripting language that they could use themselves to code all of the mechanics of plot and puzzles. Mogilefsky adapted for this task Lua, a new, still fairly obscure programming language out of Brazil. It was an inspired choice. Elegant, learnable, and yet infinitely and easily extendible, Lua has gone on to become a staple language of modern game development, to be found today in such places as the wildly popular Roblox platform.

The most frustrating aspects of GrimE from a development perspective all clustered around the spots where its two approaches to 3D graphics rubbed against one another, producing a good deal of friction in the process. If, for example, Manny was to drink a glass of whiskey, the pre-rendered version of the glass that was part of the background set had to be artfully swapped with its real-time-rendered incarnation as soon as Manny began to interact with it. Getting such actions to look seamless absorbed vastly more time and energy than anyone had expected it to.

In fact, if the bean counters had been asked to pass judgment, they would have had a hard time labeling GrimE a success at all under their metrics. Grim Fandango was in active development for almost three full years, and may have ended up costing as much as $3 million. This was at least two and a half times as much as Full Throttle had cost, and placed it in the same ballpark as The Curse of Monkey Island, LucasArts’s last and most audiovisually lavish SCUMM adventure, which was released a year before Grim Fandango. Further, despite employing a distinctly console-like control scheme in lieu of pointing and clicking with the mouse, Grim Fandango would never make it to the PlayStation; GrimE ended up being just too demanding to be made to work on such limited hardware.[2]Escape from Monkey Island, the only other game ever made using GrimE, was ported to the more capable PlayStation 2 in 2001.

All that aside, though, the new engine remained an impressive technical feat, and did succeed in realizing most of Tim Schafer’s aesthetic goals for it. Even the cost savings it apparently failed to deliver come with some mitigating factors. Making the first game with a new engine is always more expensive than making the ones that follow; there was no reason to conclude that GrimE couldn’t deliver real cost savings on LucasArts’s next adventure game. Then, too, for all that Grim Fandango wound up costing two and a half times as much as Full Throttle, it was also well over two and a half times as long as that game.

“Game production schedules are like flying jumbo jets,” says Tim Schafer. “It’s very intense at the takeoff and landing, but in the middle there’s this long lull.” The landing is the time of crunch, of course, and the crunch on Grim Fandango was protracted and brutal even by the industry’s usual standards, stretching out for months and months of sixteen- and eighteen-hour days. For by the beginning of 1998, the game was way behind schedule and way over budget, facing a marketplace that was growing more and more unkind to the adventure genre in general. This was not a combination to instill patience in the LucasArts executive suite. Schafer’s team did get the game done by the autumn of 1998, as they had been ordered to do in no uncertain terms, but only at a huge cost to their psychological and even physical health.

Bret Mogilefsky remembers coming to Schafer at one point to tell him that he just didn’t think he could go on like this, that he simply had to have a break. He was met with no sympathy whatsoever. To be fair, he probably shouldn’t have expected any. Crunch was considered par for the course in the industry during this era, and LucasArts was among the worst of its practitioners. Long hours spent toiling for ridiculously low wages — Mogilefsky was hired to be the key technical cog in this multi-million-dollar project for a salary of about $30,000 per year — were considered the price you paid for the privilege of working at The Star Wars Company.

Even setting aside the personal toll it took on the people who worked there, crunch did nothing positive for the games themselves. As we’ll see, Grim Fandango shows the scars of crunch most obviously in its dodgy puzzle design. Good puzzles result from a methodical, iterative process of testing and carefully considering the resulting feedback. Grim Fandango did not benefit from such a process, and this lack is all too plainly evident.

But before I continue making some of you very, very mad at me, let me take some time to note the strengths of Grim Fandango, which are every bit as real as its weaknesses. Indeed, if I squint just right, so that my eyes only take in its strengths, I have no problem understanding why it’s to be found on so many lists of “The Best Adventure Games Ever,” sometimes even at the very top.

There’s no denying the stuff that Grim Fandango does well. Its visual aesthetic, which I can best describe as 1930s Art Deco meets Mexican folk art meets 1940s gangster flick, is unforgettable. And it’s married to a script that positively crackles with wit and pathos. Our hero Manny is the rare adventure-game character who can be said to go through an actual character arc, who grows and evolves over the course of his story. The driving force behind the plot is his love for a woman named Meche. But his love isn’t the puppy love that Guybrush Threepwood has for Elaine in the Monkey Island games; the relationship is more nuanced, more adult, more complicated, and its ultimate resolution is all the more moving for that.

How do you create real stakes in a story where everyone is already dead? The Land of the Death’s equivalent of death is “sprouting,” in which a character is turned into a bunch of flowers and forced to live another life in that form. Why shouldn’t the dead fear life as much as the living fear death?

Tim Schafer did not grow up with the Latino traditions that are such an inextricable part of Grim Fandango. Yet the game never feels like the exercise in clueless or condescending cultural tourism it might easily have become. On the contrary, the setting feels full-bodied, lived-in, natural. The cause is greatly aided by a stellar cast of voice actors with just the right accents. The Hollywood veteran Tony Plana, who plays Manny, is particularly good, teasing out exactly the right blend of world-weary cynicism and tarnished romanticism. And Maria Canalas, who plays Meche, is equally perfect in her role. The non-verbal soundtrack by Peter McConnell is likewise superb, a mixture of mariachi music and cool jazz that shouldn’t work but does. Sometimes it soars to the forefront, but more often it tinkles away in the background, setting the mood. You’d only notice it if it was gone — but trust me, then you would really notice.

This is a big game as well as a striking and stylish one — in fact, by most reckonings the biggest adventure that LucasArts ever made. Each of its four acts, which neatly correspond to the four years that the average soul must spend wandering the underworld before going to his or her final rest, is almost big enough to be a self-contained game in its own right. Over the course of Grim Fandango, Manny goes from being a down-on-his-luck Grim Reaper cum travel agent to a nightlife impresario, from the captain of an ocean liner to a prisoner laboring in an underwater mine. The story does arguably peak too early; the second act, an extended homage to Casablanca with Manny in the role of Humphrey Bogart, is so beautifully realized that much of what follows is slightly diminished by the comparison. Be that as it may, though, it doesn’t mean any of what follows is bad.

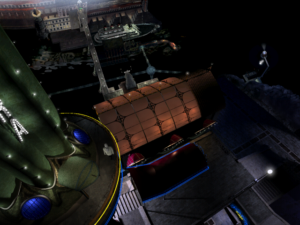

The jump cut to Manny’s new life as a bar owner in the port city of Rubacava at the beginning of the second act is to my mind the most breathtaking moment of the game, the one where you first realize how expansive its scope and ambition really are.

All told, then, I have no real beef with anyone who chooses to label Grim Fandango an aesthetic masterpiece. If there was an annual award for style in adventure games, this game would have won it easily in 1998, just as Tim Schafer’s Full Throttle would have taken the prize for 1995. Sadly, though, it seems to me that the weaknesses of both games are also the same. In both of their cases, once I move beyond the aesthetics and the storytelling and turn to the gameplay, some of the air starts to leak out of the balloon.

The interactive aspects of Grim Fandango — you know, all that stuff that actually makes it a game — are dogged by two overarching sets of problems. The first is all too typical for the adventure genre: overly convoluted, often nonsensical puzzle design. Tim Schafer was always more intrinsically interested in the worlds, characters, and stories he dreamed up than he was in puzzles. This is fair enough on the face of it; he is very, very good at those things, after all. But it does mean that he needs a capable support network to ensure that his games play as well as they look and read. He had that support for 1993’s Day of the Tentacle, largely in the person of his co-designer Dave Grossman; the result was one of the best adventure games LucasArts ever made, a perfect combination of inspired fiction with an equally inspired puzzle framework. Unfortunately, he was left to make Full Throttle on his own, and it showed. Ditto Grim Fandango. For all that he loved movies, the auteur model was not a great fit for Tim Schafer the game designer.

Grim Fandango seldom gives you a clear idea of what it is you’re even trying to accomplish. Compare this with The Curse of Monkey Island, the LucasArts adventure just before this one, a game which seemed at the time to herald a renaissance in the studio’s puzzle designs. There, you’re always provided with an explicit set of goals, usually in the form of a literal shopping list. Thus even when the mechanics of the puzzles themselves push the boundaries of real-world logic, you at least have a pretty good sense of where you should be focusing your efforts. Here, you’re mostly left to guess what Tim Schafer would like to have happen to Manny next. You stumble around trying to shake something loose, trying to figure out what you can do and then doing it just because you can. By no means is it lost on me that this sense of confusion arises to a large extent because Grim Fandango is such a character-driven story, one which eschews the mechanistic tic-tac-toe of other adventure-game plots. But recognizing this irony doesn’t make it any less frustrating when you’re wandering around with no clue what the story wants from you.

Compounding the frustrations of the puzzles are the frustrations of the interface. You don’t use the mouse at all; everything is done with the numeric keypad, or, if you’re lucky enough to have one, a console-style controller. (At the time Grim Fandango was released, virtually no one playing games on computers did.) Grim Fandango’s mode of navigation is most reminiscent of the console-based JRPGs of its era, such as the hugely popular Final Fantasy VII, which sold over 10 million copies on the PlayStation during the late 1990s. Yet in practice it’s far more irritating, because you have to interact with the environment here on a much more granular level. LucasArts themselves referred to their method of steering Manny about as a “tank” interface, a descriptor which turns out to be all too descriptive. It really does feel like you’re driving a bulky, none too agile vehicle through an obstacle course of scenery.

Make no mistake: the 3D engine makes possible some truly striking views. But too often the designers prioritize visual aesthetics over playability.

In the final reckoning, then, an approach that is fine in a JRPG makes just about every aspect of an old-school, puzzle-solving adventure game — which is what Grim Fandango remains in form and spirit when you strip all of the details of its implementation away — more awkward and less fun. Instead of having hotspots in the environment that light up when you pass a mouse cursor over them, as you do in a SCUMM adventure, you have to watch Manny’s head carefully as you drive him around; when it turns to look in a certain direction, that means there’s something he can interact with there. Needless to say, it’s all too easy to miss a turn of his head, and thereby to miss something vital to your progress through the game.

The inventory system is also fairly excruciating. Instead of being able to bring up a screen showing all of the items Manny is carrying, you have to cycle through them one by one by punching a key or controller button over and over, listening to him drone out their descriptions over and over as you do so. This approach precludes using one inventory object on another one, cutting off a whole avenue of puzzle design.

Now, the apologists among you — and this game does have an inordinate number of them — might respond to these complaints of mine by making reference to the old cliché that, for every door that is closed in life (and presumably in games as well), another one is opened. And in theory, the new engine really does open a door to new types of puzzles that are more tactile and embodied, that make you feel more a part of the game’s world. To Tim Schafer’s credit, he does try to include these sorts of puzzles in quite a few places. To our detriment, though, they turn out to be the worst puzzles in the game, relying on finicky positioning and timing and giving no useful feedback when you get those things slightly wrong.

But even when Grim Fandango presents puzzles that could easily have been implemented in SCUMM, they’re made way more annoying than they ought to be by the engine and interface. When you’re reduced to that final adventurer’s gambit of just trying everything on everything, as you most assuredly will be from time to time here, the exercise takes many times longer than it would using SCUMM, what with having to laboriously drive Manny about from place to place.

Taken as a game rather than the movie it often seems more interested in being, Grim Fandango boils down to a lumpy stew of overthought and thoughtlessness. In the former category, there’s an unpleasant ideological quality to its approach, with its prioritization of some hazy ethic of 3D-powered “immersion” and its insistence that no visible interface elements whatsoever can appear onscreen, even when these choices actively damage the player’s experience. This is where Sid Meier can helpfully step in to remind us that it is the player who is meant to be having the fun in a game, not the designer.

The thoughtlessness comes in the lack of consideration of what kind of game Grim Fandango is meant to be. Like all big-tent gaming genres, the adventure genre subsumes a lot of different styles of game with different priorities. Some adventures are primarily about exploration and puzzle solving. And that’s fine, although one does hope that those games execute their puzzles better than this one does. But Grim Fandango is not primarily about its puzzles; it wants to take you on a ride, to sweep you along on the wings of a compelling story. And boy, does it have a compelling story to share with you. For this reason, it would be best served by streamlined puzzles that don’t get too much in the way of your progress. The ones we have, however, are not only frustrating in themselves but murder on the story’s pacing, undermining what ought to be Grim Fandango’s greatest strengths. A game like this one that is best enjoyed with a walkthrough open on the desk beside it is, in this critic’s view at least, a broken game by definition.

As with so many near-miss games, the really frustrating thing about Grim Fandango is that the worst of its problems could so easily have been fixed with just a bit more testing, a bit more time, and a few more people who were empowered to push back against Tim Schafer’s more dogmatic tendencies. For the 2015 remastered version of the game, Schafer did grudgingly agree to include an alternative point-and-click interface that is more like that of a SCUMM adventure. The results verge on the transformational. By no means does the addition of a mouse cursor remedy all of the infelicities of the puzzle design, but it does make battering your way through them considerably less painful. If my less-than-systematic investigations on YouTube are anything to go by, this so-old-it’s-new-again interface has become by far the most common way to play the game today.

The Grim Fandango remaster. Note the mouse cursor. The new interface is reportedly implemented entirely in in-engine Lua scripts rather than requiring any re-programming of the GrimE engine itself. This means that it would have been perfectly possible to include as an option in the original release.

In other places, the fixes could have been even simpler than revamping the interface. A shocking number of puzzles could have been converted from infuriating to delightful by nothing more than an extra line or two of dialog from Manny or one of the other characters. As it is, too many of the verbal nudges that do exist are too obscure by half and are given only once in passing, as part of conversations that can never be repeated. Hints for Part Four are to be found only in Part One; I defy even an elephant to remember them when the time comes to apply them. All told, Grim Fandango has the distinct odor of a game that no one other than those who were too close to it to see it clearly ever really tried to play before it was put in a box and shoved out the door. There was a time when seeking the feedback of outsiders was a standard part of LucasArts’s adventure-development loop. Alas, that era was long past by the time of Grim Fandango.

Nonetheless, Grim Fandango was accorded a fairly rapturous reception in the gaming press when it was released in the last week of October in 1998, just in time for Halloween and the Mexican Day of the Dead which follows it on November 1. Its story, characters, and setting were justifiably praised, while the deficiencies of its interface and puzzle design were more often than not relegated to a paragraph or two near the end of the review. This is surprising, but not inexplicable. There was a certain sadness in the trade press — almost a collective guilt — about the diminished prospects of the adventure game in these latter years of the decade. Meanwhile LucasArts was still the beneficiary of a tremendous amount of goodwill, thanks to the many classics they had served up during those earlier, better years for the genre as a whole. Grim Fandango was held up as a sort of standard bearer for the embattled graphic adventure, the ideal mix of tradition and innovation to serve as proof that the genre was still relevant in a post-Quake, post-Starcraft world.

For many years, the standard narrative had it that the unwashed masses of gamers utterly failed to respond to the magazines’ evangelism, that Grim Fandango became an abject failure in the marketplace. In more recent years, Tim Schafer has muddied those waters somewhat by claiming that the game actually sold close to half a million copies. I rather suspect that the truth is somewhere between these two extremes. Sales of a quarter of a million certainly don’t strike me as unreasonable once foreign markets are factored into the equation. Such a figure would have been enough to keep Grim Fandango from losing much if any money, but would have provided LucasArts with little motivation to make any more such boldly original adventure games. And indeed, LucasArts would release only one more adventure game of any stripe in their history. It would use the GrimE engine, but it would otherwise play it about as safe as it possibly could, by being yet another sequel to the venerable but beloved Secret of Monkey Island.

As I was at pains to note earlier, I do see what causes some people to rate Grim Fandango so highly, and I definitely don’t think any less of them for doing so. For my part, though, I’m something of a stickler on some points. To my mind, interactivity is the very quality that separates games from other forms of media, making it hard for me to pronounce a game “good” that botches it. I’ve learned to be deeply suspicious of games whose most committed fans want to talk about everything other than that which you the player actually do in them. The same applies when a game’s creators display the same tendency. Listening to the developers’ commentary tracks in the remastered edition of Grim Fandango (who would have imagined in 1998 that games would someday come with commentary tracks?), I was shocked by how little talk there was about the gameplay. It was all lighting and dialog beats and soundtrack stabs and Z-buffers instead — all of which is really, really important in its place, but none of which can yield a great game on its own. Tellingly, when the subject of puzzle design did come up, it always seemed to be in an off-hand, borderline dismissive way. “I don’t know how players are supposed to figure out this puzzle,” says Tim Schafer outright at one point. Such a statement from your lead designer is never a good sign.

But I won’t belabor the issue any further. Suffice to say that Grim Fandango is doomed to remain a promising might-have-been rather than a classic in my book. As a story and a world, it’s kind of amazing. It’s just a shame that the gameplay part of this game isn’t equally inspired.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Grim Fandango: Prima’s Official Strategy Guide by Jo Ashburn. Retro Gamer 31 and 92; Computer Gaming World of November 1997, May 1998, and February 1999; Ultimate PC of August 1998. Plus the commentary track from the 2015 Grim Fandango remaster.

Online sources include The International House of Mojo’s pages on the game, the self-explanatory Grim Fandango Network, Gamespot’s vintage review of the game, and Daniel Albu’s YouTube conversation with Bret Mogilefsky.

And a special thank-you to reader Matt Campbell, who shared with me the audio of a talk that Bret Mogilefsky gave at the 2005 Lua Workshop, during which he explained how he used that language in GrimE.

Where to Get It: A modestly remastered version of Grim Fandango is available for digital purchase at GOG.com.