One day in early June of 1992, a group of executives from Electronic Arts visited Origin Systems’s headquarters in Austin, Texas. If they had come from any other company, the rank and file at Origin might not have paid them much attention. As it was, though, the visit felt a bit like Saddam Hussein dropping in at George Bush’s White House for a fireside chat. For Origin and EA, you see, had a history.

Back in August of 1985, just prior to the release of Ultima IV, the much smaller Origin had signed a contract to piggyback on EA’s distribution network as an affiliated label. Eighteen months later, when EA released an otherwise unmemorable CRPG called Deathlord whose interface hewed a little too closely to that of an Ultima, a livid Richard Garriott attempted to pull Origin out of the agreement early. EA at first seemed prepared to crush Origin utterly in retribution by pulling at the legal seams in the two companies’ contract. Origin, however, found themselves a protector: Brøderbund Software, whose size and clout at the time were comparable to that of EA. At last, EA agreed to allow Origin to go their own way, albeit probably only after the smaller company paid them a modest settlement for breaking the contract. Origin quickly signed a new distribution contract with Brøderbund, which lasted until 1989, by which point they had become big enough in their own right to take over their own distribution.

But Richard Garriott wasn’t one to forgive even a small personal slight easily, much less a full-blown threat to destroy his company. From 1987 on, EA was Public Enemy #1 at Origin, a status which Garriott marked in ways that only seemed to grow pettier as time went on. Garriott built a mausoleum for “Pirt Snikwah” — the name of Trip Hawkins, EA’s founder and chief executive, spelled backward — at his Austin mansion of Britannia Manor. Ultima V‘s parser treated the phrase “Electronic Arts” like a curse word; Ultima VI included a gang of evil pirates named after some of the more prominent members of EA’s executive staff. Time really did seem to make Garriott more rather than less bitter. Among his relatively few detail-oriented contributions to Ultima VII were a set of infernal inter-dimensional generators whose shapes together formed the EA logo. He also demanded that the two villains who went on a murder spree across Britannia in that game be named Elizabeth and Abraham. Just to drive the point home, the pair worked for a “Destroyer of Worlds” — an inversion of Origin’s longstanding tagline of “We Create Worlds.”

And yet here the destroyers were, just two months after the release of Ultima VII, chatting amiably with their hosts while they gazed upon their surroundings with what seemed to some of Origin’s employees an ominously proprietorial air. Urgent speculation ran up and down the corridors: what the hell was going on? In response to the concerned inquiries of their employees, Origin’s management rushed to say that the two companies were merely discussing “some joint ventures in Sega Genesis development,” even though “they haven’t done a lot of cooperative projects in the past.” That was certainly putting a brave face on half a decade of character assassination!

What was really going on was, as the more astute employees at Origin could all too plainly sense, something far bigger than any mere “joint venture.” The fact was, Origin was in a serious financial bind — not a unique one in their evolving industry, but one which their unique circumstances had made more severe for them than for most others. Everyone in the industry, Origin included, was looking ahead to a very near future when the enormous storage capacity of CD-ROM, combined with improving graphics and sound and exploding numbers of computers in homes, would allow computer games to join television, movies, and music as a staple of mainstream entertainment rather than a niche hobby. Products suitable for this new world order needed to go into development now in order to be on store shelves to greet it when it arrived. These next-generation products with their vastly higher audiovisual standards couldn’t be funded entirely out of the proceeds from current games. They required alternative forms of financing.

For Origin, this issue, which really was well-nigh universal among their peers, was further complicated by the realities of being a relatively small company without a lot of product diversification. A few underwhelming attempts to bring older Ultima games to the Nintendo Entertainment System aside, they had no real presence on videogame consoles, a market which dwarfed that of computer games, and had just two viable product lines even on computers: Ultima and Wing Commander. This lack of diversification left them in a decidedly risky position, where the failure of a single major release in either of those franchises could conceivably bring down the whole company.

The previous year of 1991 had been a year of Wing Commander, when the second mainline title in that franchise, combined with ongoing strong sales of the first game and a series of expansion packs for both of them, had accounted for fully 90 percent of the black ink in Origin’s books. In this year of 1992, it was supposed to have been the other franchise’s turn to carry the company while Wing Commander retooled its technology for the future. But Ultima VII: The Black Gate, while it had been far from an outright commercial failure, had garnered a more muted response than Origin had hoped and planned for, plagued as its launch had been by bugs, high system requirements, and the sheer difficulty of configuring it to run properly under the inscrutable stewardship of MS-DOS.

Even more worrisome than all of the specific issues that dogged this latest Ultima was a more diffuse sort of ennui directed toward it by gamers — a sense that the traditional approach of Ultima in general, with its hundred-hour play time, its huge amounts of text, and its emphasis on scope and player freedom rather than multimedia set-pieces, was falling out of step with the times. Richard Garriott liked to joke that he had spent his whole career making the same game over and over — just making it better and bigger and more sophisticated each time out. It was beginning to seem to some at Origin that that progression might have reached its natural end point. Before EA ever entered the picture, a sense was dawning that Ultima VIII needed to go in another direction entirely — needed to be tighter, flashier, more focused, more in step with the new types of customers who were now beginning to buy computer games. Ultima Underworld, a real-time first-person spinoff of the core series developed by the Boston studio Blue Sky Productions rather than Origin themselves, had already gone a considerable distance in that direction, and upon its near-simultaneous release with Ultima VII had threatened to overshadow its more cerebral big brother completely, garnering more enthusiastic reviews and, eventually, higher sales. Needless to say, had Ultima Underworld not turned into such a success, Origin’s financial position would have been still more critical than it already was. It seemed pretty clear that this was the direction that all of Ultima needed to go.

But making a flashier next-generation Ultima VIII — not to mention the next-generation Wing Commander — would require more money than even Ultima VII and Ultima Underworld together were currently bringing in. And yet, frustratingly, Origin couldn’t seem to drum up much in the way of financing. Their home state of Texas was in the midst of an ugly series of savings-and-loan scandals that had made all of the local banks gun-shy; the country as a whole was going through a mild recession that wasn’t helping; would-be private investors could see all too clearly the risks associated with Origin’s non-diversified business model. As the vaguely disappointing reception for Ultima VII continued to make itself felt, the crisis began to feel increasingly existential. Origin had lots of technical and creative talent and two valuable properties — Wing Commander in particular was arguably still the hottest single name in computer gaming — but had too little capital and a nonexistent credit line. They were, in other words, classic candidates for acquisition.

It seems that the rapprochement between EA and Origin began at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago at the very beginning of June of 1992, and, as evidenced by EA’s personal visit to Origin just a week or so later, proceeded rapidly from there. It would be interesting and perhaps a little amusing to learn how the rest of Origin’s management team coaxed Richard Garriott around to the idea of selling out to the company he had spent the last half-decade vilifying. But whatever tack they took, they obviously succeeded. At least a little bit of sugar was added to the bitter pill by the fact that Trip Hawkins, whom Garriott rightly or wrongly regarded as the worst of all the fiends at EA, had recently stepped down from his role in the company’s management to helm a new semi-subsidiary outfit known as 3DO. (“Had Trip still been there, there’s no way we would have gone with EA,” argues one former Origin staffer — but, then again, necessity can almost always make strange bedfellows.)

Likewise, we can only wonder what if anything EA’s negotiators saw fit to say to Origin generally and Garriott specifically about all of the personal attacks couched within the last few Ultima games. I rather suspect they said nothing; if there was one thing the supremely non-sentimental EA of this era had come to understand, it was that it seldom pays to make business personal.

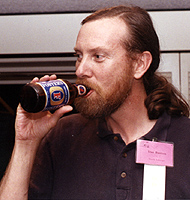

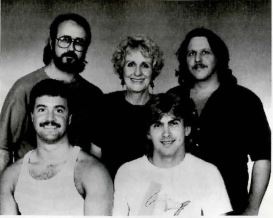

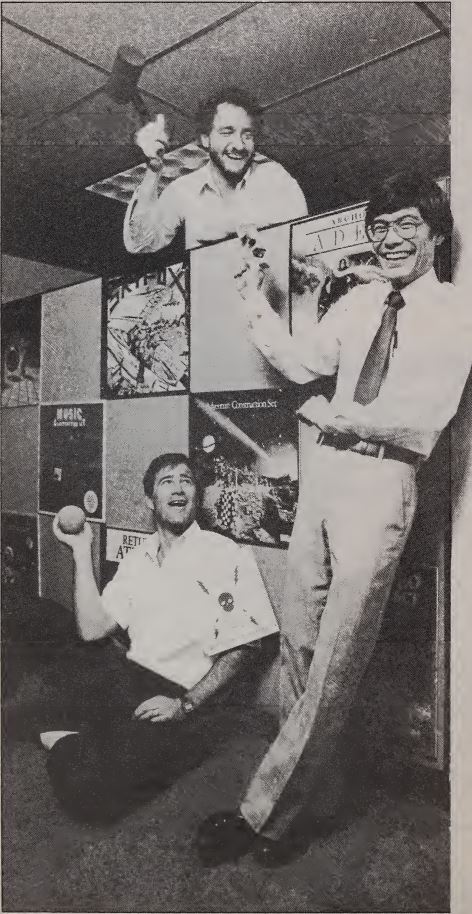

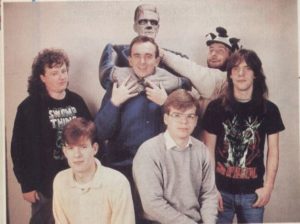

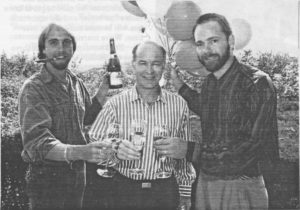

Richard and Robert Garriott flank Stan McKee, Electronic Arts’s chief financial officer, as they toast the consummation of one of the more unexpected acquisitions in gaming history at EA’s headquarters in San Mateo, California.

So, the deal was finalized at EA’s headquarters in San Mateo, California, on September 25, 1992, in the form of a stock exchange worth $35 million. Both parties were polite enough to call it a merger rather than an acquisition, but it was painfully clear which one had the upper hand; EA, who were growing so fast they had just gone through a two-for-one stock split, now had annual revenues of $200 million, while Origin could boast of only $13 million. In a decision whose consequences remain with us to this day, Richard Garriott even agreed to sign over his personal copyrights to the Ultima franchise. In return, he became an EA vice president; his brother Robert, previously the chief executive in Austin, now had to settle for the title of the new EA subsidiary’s creative director.

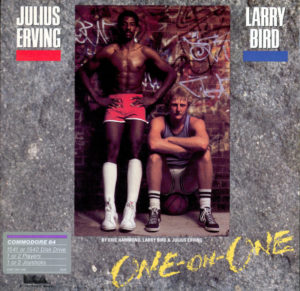

From EA’s perspective, the deal got them Ultima, a franchise which was perhaps starting to feel a little over-exposed in the wake of a veritable flood of Origin product bearing the name, but one which nevertheless represented EA’s first viable CRPG franchise since the Bard’s Tale trilogy had concluded back in 1988. Much more importantly, though, it got them Wing Commander, in many ways the progenitor of the whole contemporary craze for multimedia “interactive movies”; it was a franchise which seemed immune to over-exposure. (Origin had amply proved this point by releasing two Wing Commander mainline games and four expansion packs in the last two years, plus a “Speech Accessory Pack” for Wing Commander II, all of which had sold very well indeed.)

As you do in these situations, both management teams promised the folks in Austin that nothing much would really change. “The key word is autonomy,” Origin’s executives said in their company’s internal newsletter. “Origin is supposed to operate independently from EA and maintain profitability.” But of course things did — had to — change. There was an inescapable power imbalance here, such that, while Origin’s management had to “consult” with EA when making decisions, their counterparts suffered no such obligation. And of course what might happen if Origin didn’t “maintain profitability” remained unspoken.

Thus most of the old guard at Origin would go on to remember September 25, 1992, as, if not quite the end of the old, freewheeling Origin Systems, at least the beginning of the end. Within six months, resentments against the mother ship’s overbearing ways were already building in such employees as an anonymous letter writer who asked his managers why they were “determined to eradicate the culture that makes Origin such a fun place to work.” Within a year, another was asking even more heatedly, “What happened to being a ‘wholly owned independent subsidiary of EA?’ When did EA start telling Origin what to do and when to do it? I thought Richard said we would remain independent and that EA wouldn’t touch us?!? Did I miss something here?” Eighteen months in, an executive assistant named Michelle Caddel, the very first new employee Origin had hired upon opening their Austin office in 1987, tried to make the best of the changes: “Although some of the warmth at Origin has disappeared with the merger, it still feels like a family.” For now, at any rate.

Perhaps tellingly, the person at Origin who seemed to thrive most under the new arrangement was one of the most widely disliked: Dallas Snell, the hard-driving production manager who was the father of a hundred exhausting crunch times, who tended to regard Origin’s games as commodities quantifiable in floppy disks and megabytes. Already by the time Origin had been an EA subsidiary for a year, he had managed to install himself at a place in the org chart that was for all practical purposes above that of even Richard and Robert Garriott: he was the only person in Austin who was a “direct report” to Bing Gordon, EA’s powerful head of development.

On the other hand, becoming a part of the growing EA empire also brought its share of advantages. The new parent company’s deep pockets meant that Origin could prepare in earnest for that anticipated future when games would sell more copies but would also require more money, time, and manpower to create. Thus almost immediately after closing the deal with EA, Origin closed another one, for a much larger office space which they moved into in January of 1993. Then they set about filling up the place; over the course of the next year, Origin would double in size, going from 200 to 400 employees.

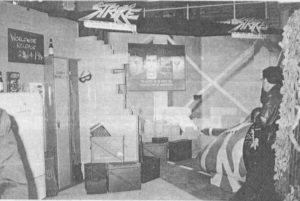

The calm before the storm: the enormous cafeteria at Origin’s new digs awaits the first onslaught of hungry employees. Hopefully someone will scrounge up some tables and chairs before the big moment arrives…

And so the work of game development went on. When EA bought Origin, the latter naturally already had a number of products, large and small, in the pipeline. The first-ever expansion pack for an existing Ultima game — an idea borrowed from Wing Commander — was about to hit stores; Ultima VII: Forge of Virtue would prove a weirdly unambitious addition to a hugely ambitious game, offering only a single dungeon to explore that was more frustrating than fun. Scheduled for release in 1993 were Wing Commander: Academy, a similarly underwhelming re-purposing of Origin’s internal development tools into a public-facing “mission builder,” and Wing Commander: Privateer, which took the core engine and moved it into a free-roaming framework rather than a tightly scripted, heavily story-driven one; it thus became a sort of updated version of the legendary Elite, and, indeed, would succeed surprisingly well on those terms. And then there was also Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds, developed like its predecessor by Blue Sky up in Boston; it would prove a less compelling experience on the whole than Ultima Underworld I, being merely a bigger game rather than a better one, but it would be reasonably well-received by customers eager for more of the same.

Those, then, were the relatively modest projects. Origin’s two most expensive and ambitious games for the coming year consisted of yet one more from the Ultima franchise and one that was connected tangentially to Wing Commander. We’ll look at them a bit more closely, taking them one at a time.

The game which would be released under the long-winded title of Ultima VII Part Two: Serpent Isle had had a complicated gestation. It was conceived as Origin’s latest solution to a problem that had long bedeviled them: that of how to leverage their latest expensive Ultima engine for more than one game without violating the letter of a promise Richard Garriott had made more than a decade before to never use the same engine for two successive mainline Ultima games. Back when Ultima VI was the latest and greatest, Origin had tried reusing its engine in a pair of spinoffs called the Worlds of Ultima, which rather awkwardly shoehorned the player’s character from the main series — the “Avatar” — into plots and settings that otherwise had nothing to do with Richard Garriott’s fantasy world of Britannia. Those two games had drawn from early 20th-century science and adventure fiction rather than Renaissance Faire fantasy, and had actually turned out quite magnificently; they’re among the best games ever to bear the Ultima name in this humble critic’s opinion. But, sadly, they had sold like the proverbial space heaters in the Sahara. It seemed that Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Rice Burroughs were a bridge too far for fans raised on J.R.R. Tolkien and Lord British.

So, Origin adjusted their approach when thinking of ways to reuse the even more expensive Ultima VII engine. They conceived two projects. One would be somewhat in the spirit of Worlds of Ultima, but would stick closer to Britannia-style fantasy: called Arthurian Legends, it would draw from, as you might assume, the legends of King Arthur, a fairly natural thematic fit for a series whose creator liked to call himself “Lord British.” The other game, the first to go into production, would be a direct sequel to Ultima VII, following the Avatar as he pursued the Guardian, that “Destroyer of Worlds” from the first game, from Britannia to a new world. This game, then, was Serpent Isle. Originally, it was to have had a pirate theme, all fantastical derring-do on an oceanic world, with a voodoo-like magic system in keeping with Earthly legends of Caribbean piracy.

This piratey Serpent Isle was first assigned to Origin writer Jeff George, but he struggled to find ways to adapt the idea to the reality of the Ultima VII engine’s affordances. Finally, after spinning his wheels for some months, he left the company entirely. Warren Spector, who had become Origin’s resident specialist in Just Getting Things Done, then took over the project and radically revised it, dropping the pirate angle and changing the setting to one that was much more Britannia-like, right down to a set of towns each dedicated to one of a set of abstract virtues. Having thus become a less excitingly original concept but a more practical one from a development perspective, Serpent Isle started to make good progress under Spector’s steady hand. Meanwhile another small team started working up a script for Arthurian Legends, which was planned as the Ultima VII engine’s last hurrah.

Yet the somewhat muted response to the first Ultima VII threw a spanner in the works. Origin’s management team was suddenly second-guessing the entire philosophy on which their company had been built: “Do we still create worlds?” Arthurian Legends was starved of resources amidst this crisis of confidence, and finally cancelled in January of 1993. Writer and designer Sheri Graner Ray, one of only two people left on the project at the end, invests its cancellation with major symbolic importance:

I truly believe that on some level we knew that this was the death knell for Origin. It was the last of the truly grass-roots games in production there… the last one that was conceived, championed, and put into development purely by the actual developers, with no support or input from the executives. It was actually, kinda, the end of an era for the game industry in general, as it was also during this time that we were all adjusting to the very recent EA buyout of Origin.

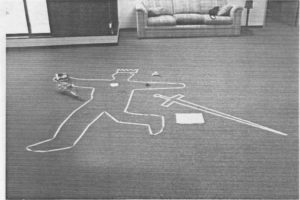

Brian Martin, one of the last two developers remaining on the Arthurian Legends project, made this odd little memorial to it with the help of his partner Sheri Graner Ray after being informed by management that the project was to be cancelled entirely. Ray herself tells the story: “Before we left that night, Brian laid down in the common area that was right outside our office and I went around his body with masking tape… like a chalk line… we added the outline of a crown and the outline of a sword. We then draped our door in black cloth and put up a sign that said, ‘The King is Dead. Long live the King.’ …. and a very odd thing happened. The next morning when we arrived, there were flowers by the outline. As the day wore on more flowers arrived.. and a candle.. and some coins were put on the eyes… and a poem arrived… it was uncanny. This went on for several days with the altar growing more and more. Finally, we were told we had to take it down, because there was a press junket coming through and they didn’t want the press seeing it.”

Serpent Isle, on the other hand, was too far along by the time the verdict was in on the first Ultima VII to make a cancellation realistic. It would instead go down in the recollection of most hardcore CRPG fans as the last “real” Ultima, the capstone to the process of evolution a young Richard Garriott had set in motion back in 1980 with a primitive BASIC game called Akalabeth. And yet the fact remains that it could have been so, so much better, had it only caught Origin at a less uncertain, more confident time.

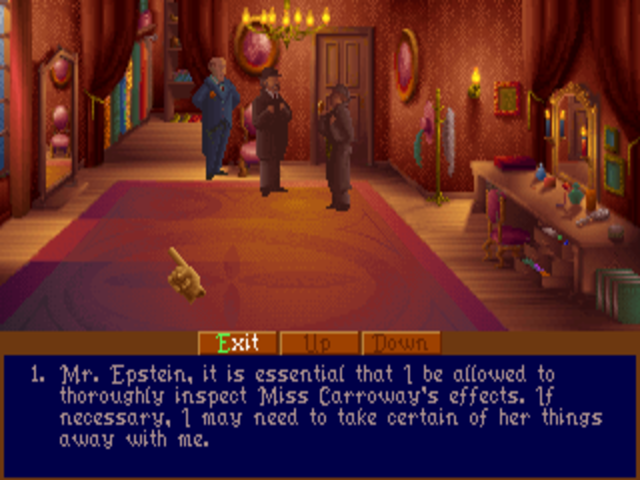

Serpent Isle lacks the refreshingly original settings of the two Worlds of Ultima games, as it does the surprisingly fine writing of the first Ultima VII; Raymond Benson, the head writer on the latter project, worked on Serpent Isle only briefly before decamping to join MicroProse Software. In compensation, though, Serpent Isle is arguably a better game than its predecessor through the first 65 percent or so of its immense length. Ultima VII: The Black Gate can at times feel like the world’s most elaborate high-fantasy walking simulator; you really do spend most of your time just walking around and talking to people, an exercise that’s made rewarding only by the superb writing. Serpent Isle, by contrast, is full to bursting with actual things to do: puzzles to solve, dungeons to explore, quests to fulfill. It stretches its engine in all sorts of unexpected and wonderfully hands-on directions. Halfway in, it seems well on its way to being one of the best Ultima games of all, as fine a sendoff as any venerable series could hope for.

In the end, though, its strengths were all undone by Origin’s crisis of faith in the traditional Ultima concept. Determined to get its sales onto the books of what had been a rather lukewarm fiscal year and to wash their hands of the past it now represented, management demanded that it go out on March 25, 1993, the last day of said year. As a result, the last third or so of Serpent Isle is painfully, obviously unfinished. Conversations become threadbare, plot lines are left to dangle, side quests disappear, and bugs start to sprout up everywhere you look. As the fiction becomes a thinner and thinner veneer pasted over the mechanical nuts and bolts of the design, solubility falls by the wayside. By the end, you’re wandering through a maze of obscure plot triggers that have no logical connection with the events they cause, making a walkthrough a virtual necessity. It’s a downright sad thing to have to witness. Had its team only been allowed another three or four months to finish the job, Serpent Isle could have been not only a great final old-school Ultima but one of the best CRPGs of any type that I’ve ever played, a surefire entrant in my personal gaming hall of fame. As it is, though, it’s a bitter failure, arguably the most heartbreaking one of Warren Spector’s storied career.

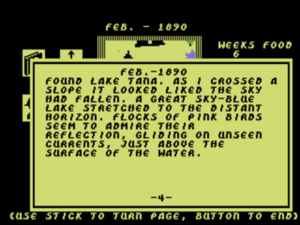

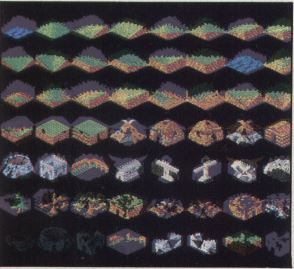

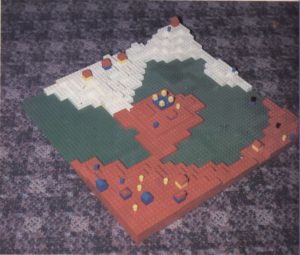

Unfashionable though such an approach was in 1993, almost all of the Serpent Isle team’s energy went into gameplay and script rather than multimedia assets; the game looks virtually identical to the first Ultima VII. An exception is the frozen northlands which you visit later in the game. Unfortunately, the change in scenery comes about the time that the design slowly begins to fall apart.

And there was to be one final note of cutting irony in all of this: Serpent Isle, which Origin released without a lot of faith in its commercial potential, garnered a surprisingly warm reception among critics and fans alike, and wound up selling almost as well as the first Ultima VII. Indeed, it performed so well that the subject of doing “more games in that vein,” in addition to or even instead of a more streamlined Ultima VIII, was briefly discussed at Origin. As things transpired, though, its success led only to an expansion pack called The Silver Seed before the end of the year; this modest effort became the true swansong for the Ultima VII engine, as well as the whole era of the 100-hour-plus, exploration-focused, free-form single-player CRPG at Origin in general. The very philosophy that had spawned the company, that had been at the core of its identity for the first decade of its existence, was fading into history. Warren Spector would later have this to say in reference to a period during which practical commercial concerns strangled the last shreds of idealism at Origin:

There’s no doubt RPGs were out of favor by the mid-90s. No doubt at all. People didn’t seem to want fantasy stories or post-apocalypse stories anymore. They certainly didn’t want isometric, 100 hour fantasy or post-apocalypse stories, that’s for sure! I couldn’t say why it happened, but it did. Everyone was jumping on the CD craze – it was all cinematic games and high-end-graphics puzzle games… That was a tough time for me – I mean, picture yourself sitting in a meeting with a bunch of execs, trying to convince them to do all sorts of cool games and being told, “Warren, you’re not allowed to say the word ‘story’ any more.” Talk about a slap in the face, a bucket of cold water, a dose of reality.

If you ask me, the reason it all happened was that we assumed our audience wanted 100 hours of play and didn’t care much about graphics. Even high-end RPGs were pretty plain-jane next to things like Myst and even our own Wing Commander series. I think we fell behind our audience in terms of the sophistication they expected and we catered too much to the hardcore fans. That can work when you’re spending hundreds of thousands of dollars – even a few million – but when games start costing many millions, you just can’t make them for a relatively small audience of fans.

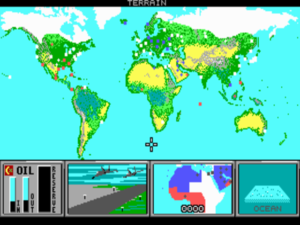

If Serpent Isle and its expansion were the last gasps of the Origin Systems that had been, the company’s other huge game of 1993 was every inch a product of the new Origin that had begun to take shape following the worldwide success of the first Wing Commander game. Chris Roberts, the father of Wing Commander, had been working on something called Strike Commander ever since late 1990, leaving Wing Commander II and all of the expansion packs and other spinoffs in the hands of other Origin staffers. The new game took the basic idea of the old — that of an action-oriented vehicular simulator with a strong story, told largely via between-mission dialog scenes — and moved it from the outer space of the far future to an Earth of a very near future, where the international order has broken down and mercenaries battle for control over the planet’s dwindling resources. You take to the skies in an F-16 as one of the mercenaries — one of the good ones, naturally.

Origin and Chris Roberts pulled out all the stops to make Strike Commander an audiovisual showcase; the game’s gestation time of two and a half years, absurdly long by the standards of the early 1990s, was a product of Roberts constantly updating his engine to take advantage of the latest cutting-edge hardware. The old Wing Commander engine was starting to look pretty long in the tooth by the end of 1992, so this new engine, which replaced its predecessor’s scaled sprites with true polygonal 3D graphics, was more than welcome. There’s no point in putting a modest face on it: Strike Commander looked downright spectacular in comparison with any other flight simulator on offer at the time. It was widely expected, both inside and outside of Origin, to become the company’s biggest game ever. In fact, it became the first Origin game to go gold in the United States — 100,000 copies sold to retail — before it had actually shipped there, thanks to the magic of pre-orders. Meanwhile European pre-orders topped 50,000, an all-time record for EA’s British subsidiary. All in all, more than 1.1 million Strike Commander floppy disks — 30 tons worth of plastic, metal, and iron oxide — were duplicated before a single unit was sold. Why not? This game was a sure thing.

The hype around Strike Commander was inescapable for months prior to its release. At the European Computer Trade Show in London, the last big event before the release, Origin put together a mock-up of an airplane hangar. Those lucky people who managed to seize control for a few minutes got to play the game from behind a nose cowl and instrument panel. What Origin didn’t tell you was that the computer hidden away underneath all the window dressing was almost certainly much, much more powerful than one you had at home.

Alas, pride goeth before a fall. Just a couple of weeks after Strike Commander‘s worldwide release on April 23, 1993, Origin had to admit to themselves in their internal newsletter that sales from retail to actual end users were “slower than expected.” Consumers clearly weren’t as enamored with the change in setting as Origin and just about everyone else in their industry had assumed they would be. Transporting the Wing Commander formula into a reasonably identifiable version of the real world somehow made the story, which hovered as usual in some liminal space between comic book and soap opera, seem rather more than less ludicrous. At the same time, the use of an F-16 in place of a made-up star fighter, combined with the game’s superficial resemblance to the hardcore flight simulators of the day, raised expectations among some players which the game had never really been designed to meet. The editors of Origin’s newsletter complained, a little petulantly, about this group of sim jockeys who were “ready for a cockpit that had every gauge, altimeter, dial, and soft-drink holder in its proper place. This is basically the group which wouldn’t be happy unless you needed the $35 million worth of training the Air Force provides just to get the thing off the ground.” There were advantages, Origin was belatedly learning, to “simulating” a vehicle that had no basis in reality, as there were to fictions similarly divorced from the real world. In hitting so much closer to home, Strike Commander lost a lot of what had made Wing Commander so appealing.

The new game’s other problem was more immediate and practical: almost no one could run the darn thing well enough to actually have the experience Chris Roberts had intended it to be. Ever since Origin had abandoned the Apple II to make MS-DOS their primary development platform at the end of the 1980s, they’d had a reputation for pushing the latest hardware to its limit. This game, though, was something else entirely even from them. The box’s claim that it would run on an 80386 was a polite fiction at best; in reality, you needed an 80486, and one of the fastest ones at that — running at least at 50 MHz or, better yet, 66 MHz — if you wished to see anything like the silky-smooth visuals that Origin had been showing off so proudly at recent trade shows. Even Origin had to admit in their newsletter that customers had been “stunned” by the hardware Strike Commander craved. Pushed along by the kid-in-a-candy-store enthusiasm of Chris Roberts, who never had a passing fancy he didn’t want to rush right out and implement, they had badly overshot the current state of computing hardware.

Of course, said state was always evolving; it was on this fact that Origin now had to pin whatever diminished hopes they still had for Strike Commander. The talk of the hardware industry at the time was Intel’s new fifth-generation microprocessor, which abandoned the “x86” nomenclature in favor of the snazzy new focus-tested name of Pentium, another sign of how personal computers were continuing their steady march from being tools of businesspeople and obsessions of nerdy hobbyists into mainstream consumer-electronics products. Origin struck a promotional deal with Compaq Computers in nearby Houston, who, following what had become something of a tradition for them, were about to release the first mass-market desktop computer to be built around this latest Intel marvel. Compaq placed the showpiece that was Strike Commander-on-a-Pentium front and center at the big PC Expo corporate trade show that summer of 1993, causing quite a stir at an event that usually scoffed at games. “The fuse has only been lit,” went Origin’s cautiously optimistic new company line on Strike Commander, “and it looks to be a long and steady burn.”

But time would prove this optimism as well to be somewhat misplaced: one of those flashy new Compaq Pentium machines cost $7000 in its most minimalist configuration that summer. By the time prices had come down enough to make a Pentium affordable for gamers without an absurd amount of disposable income, other games with even more impressive audiovisuals would be available for showing off their hardware. Near the end of the year, Origin released an expansion pack for Strike Commander that had long been in the development pipeline, but that would be that: there would be no Strike Commander II. Chris Roberts turned his attention instead to Wing Commander III, which would raise the bar on development budget and multimedia ambition to truly unprecedented heights, not only for Origin but for their industry at large. After all, Wing Commander: Academy and Privateer, both of which had had a fraction of the development budget of Strike Commander but wound up selling just as well, proved that there was still a loyal, bankable audience out there for the core series.

Origin had good reason to play it safe now in this respect and others. When the one-year anniversary of the acquisition arrived, the accountants had to reveal to EA that their new subsidiary had done no more than break even so far. By most standards, it hadn’t been a terrible year at all: Ultima Underworld II, Serpent Isle, Wing Commander: Academy, and Wing Commander: Privateer had all more or less made money, and even Strike Commander wasn’t yet so badly underwater that all hope was lost on that front. But on the other hand, none of these games had turned into a breakout hit in the fashion of the first two Wing Commander games, even as the new facilities, new employees, and new titles going into development had cost plenty. EA was already beginning to voice some skepticism about some of Origin’s recent decisions. The crew in Austin really, really needed a home run rather than more base hits if they hoped to maintain their status in the industry and get back into their overlord’s good graces. Clearly 1994, which would feature a new mainline entry in both of Origin’s core properties for the first time since Ultima VI had dropped and Wing Commander mania had begun back in 1990, would be a pivotal year. Origin’s future was riding now on Ultima VIII and Wing Commander III.

(Sources: the book Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture from Geek to Chic by Brad King and John Borland; Origin’s internal newsletter Point of Origin from March 13 1992, June 19 1992, July 31 1992, September 25 1992, October 23 1992, November 6 1992, December 4 1992, December 18 1992, January 29 1993, February 12 1993, February 26 1993, March 26 1993, April 9 1993, April 23 1993, May 7 1993, May 21 1993, June 18 1993, July 2 1993, August 27 1993, September 10 1993, October 13 1993, October 22 1993, November 8 1993, and December 1993; Questbusters of April 1986 and July 1987; Computer Gaming World of October 1992 and August 1993. Online sources include “The Conquest of Origin” at The Escapist, “The Stars His Destination: Chris Roberts from Origin to Star Citizen“ at US Gamer, Shery Graner Ray’s blog entry “20 Years and Counting — Origin Systems,” and an interview with Warren Spector at RPG Codex.

All of the Origin games mentioned in this article are available for digital purchase at GOG.com.)