This sign, executed in throwback 1980s Ultima iconography, hung on the wall outside the elevator on the fifth floor of Origin Systems’s office building, pointing the way to the Multima team. If you neglected to follow the sign’s advice and turned left instead of right here, you would plunge five stories to your doom.

To carry our story forward into the next phase of persistent online multiplayer gaming, we first need to go backward again — all the way back to the days when tabletop Dungeons & Dragons was new on the scene and people were first beginning to imagine how computers might make it more accessible. Some dreamed of eliminating the pesky need for other humans to play with entirely; others wondered whether it might be possible to use networked computers in place of the tabletop, so that you could get together and play with your friends without all of the logistical complications of meeting up in person. Still others dreamed bigger, dreamed of things that would never be possible even with a tabletop big enough to make King Arthur blush. What if you could use computers to make a living virtual world with thousands of human inhabitants? In a column in a 1983 issue of Starlog magazine, Lenny Kaye mused about just such a thing.

When played among groups of people, [tabletop] RPGs foster a sense of cooperation toward a common goal, something videogames have hardly approached.

But with the computer’s aid, the idea of the game network can expand outward, interfacing with all sorts of societal drifts. The technology for both video[games] and RPGs is still in its infancy — one with graphics and memory far from ideal, the other still attached to its boards and figurines — and yet, it’s not hard to imagine a nationwide game, in which all citizens play their part. Perhaps it becomes an arena in which to exercise and exorcise ourselves, releasing our animal instincts through the power of the mind, understanding the uses and misuses of our humanity.

While they waited for the technology which could make that dream a reality to appear, people did what they could with what they had. The ones who came closest to the ideal of a “nationwide game” were those running MUDs, those “multi-user dungeons” that allowed up to 100 players to interact with one another by typing commands into a textual parser, with teletype-style streaming text as their eyes and ears into the world they all shared.

Island of Kesmai did soon come along on the big online service CompuServe, with an interface that looked more like Rogue than the original game of Adventure. But again, only 100 people could play together simultaneously there, about the same number as on the biggest MUDs. And in this case, each of them had to pay by the minute for the privilege. For all that it was amazing that it could exist at all in its time and place, Island of Kesmai was more like a wealthy gated village than a teeming virtual world.

Still, it must be acknowledged that the sellers of traditional boxed computer games were even farther away from that aspiration, being content to offer up single-player CRPGs where combat — that being the aspect of tabletop RPGs that was easiest to implement on a computer — tended to overwhelm everything else. The one obvious exception to this norm was Origin Systems of Austin, Texas. Especially after 1985’s landmark Ultima IV, Origin’s Ultima series became not only the commercial standard bearer for CRPGs but the best argument for the genre’s potential to be about something more than statistics and combat tactics. These games were rather about world-building and about the Virtues of the (player’s) Avatar, daring to introduce an ethical philosophy that was applicable to the real world — and then, in later installments, to muddy the waters by mercilessly probing the practical limitations and blind spots inherent in any such rigid ethical code.

Richard Garriott — “Lord British” to his legion of fans, the creator of Ultima and co-founder of Origin — had first conceived of the games as a re-creation of the tabletop Dungeons & Dragons sessions that had made him a minor celebrity in his Houston neighborhood well before he got his hands on his first Apple II. The setting of computerized Ultima was the world of Britannia, the same one he had invented for his high-school friends. The idea of adventuring together with others through the medium of the computer thus made a lot of sense to him. Throughout the 1980s and beyond, he repeatedly brought up the hypothetical game that he called Multima, a multiplayer version of Ultima. In 1987, an Origin programmer was actually assigned to work on it for a while. Garriott, from a contemporary interview:

James Van Artsdalen, who does our IBM and Macintosh translations, is working on a program that lets several people participate in the game. Two people can do this with different computers directly connected via modems, or even more can play via a system with multiple modems. We don’t know if we’ll be able to support packet networks like CompuServe because they may be too slow for this application. We’ll do it if we can.

What you’ll buy in the store will be a package containing all the core graphics routines and the game-development stuff (all the commands and so on), which you could even plug into your computer and play as a standalone. But with a modem you could tie a friend into the game, or up to somewhere between eight and sixteen other players, all within the same game.

We will most likely run a game of this out of our office. Basically, we can almost gamemaster it. There could be a similar setup in each town, and anybody could run one. Our intention is to let anyone capable of having multiple modems on their system have the network software. Anybody can be a node: two people can play if they each own a package, just by calling each other. But to be a base, a multiplayer node, you’ve got to have multiple modems and may need additional software. If the additional software is needed, we’ll let anyone who wants it have it, since we’re just supporting sales of our own products anyway.

Should be a lot of fun, we think. We hope to have it out by next summer [the summer of 1988], and it should cost between $30 and $60. This will be able to tie different kinds of computers together, since the information being sent back and forth doesn’t include any graphics. I could play on my Apple while you’re on your IBM, for instance. The graphics will be full state-of-the-art Ultima graphics, but they’ll already be on your computer.

Alas, this Multima was quietly abandoned soon after the interview, having been judged just too uncertain a project to invest significant resources into when there was guaranteed money to be made from each new single-player Ultima. As we’ll soon see, it was not the last time that argument was made against a Multima.

Circa 1990, Multima was revived for a time, this time as a three-way partnership among Origin, the commercial online service GEnie, and Kesmai, the maker of Island of Kesmai. The last would be given the source code to Ultima VI, the latest iteration of the single-player series, and would adapt it for online play, after which GEnie would deploy it on its central mainframe. As it happened, a similar deal was already taking SSI’s Gold Box engine for licensed Dungeons & Dragons CRPGs through the same process of transformation. It would result in something called Neverwinter Nights[1]Not the same game as the 2002 Bioware CRPG of the same name. going up on America Online in 1991 with an initial capacity of 100 simultaneous players, eventually to be raised by popular demand to 500, making it the most massively multiplayer online game of the early 1990s. But Multima was not so lucky; the deal fell through before it had gotten beyond the planning stages, perchance having proved a simple case of too many cooks in the kitchen.

Richard Garriott had largely ceased to involve himself in the day-to-day work of making new Ultima games by this point, but he continued to set the overall trajectory of the franchise. And as he did so, he never forgot those old hopes for a Multima. Not long after Electronic Arts (EA) purchased Origin Systems in 1992, he thought he saw the stars aligning at long last. For 1993 brought with it NCSA Mosaic, the first broadly popular multimedia Web browser, the harbinger of the home Internet boom. This newly accessible public Internet could replace fragile peer-to-peer modems connections as easily as it could the bespoke private networks of CompuServe and GEnie, making the likes of Multima seem far more practical, both to implement and to offer to customers at an affordable price.

For better or for worse, though, Origin was now a part of EA, who had the final say on which projects got funded. Garriott tried repeatedly over a period of a year and a half or more to interest EA’s CEO Larry Probst in his Multima schemes, without success. As he tells the story, he and a couple of other true believers from Origin resorted to guerrilla tactics at the third formal pitch meeting.

We literally just refused to give up the floor. They said, “No. Get out.” And we stomped our feet and held our breath. “We are not leaving until you guys get a clue. As a developer, we go over-budget by 25 to 50 percent every year. We’re only asking for $250,000 to build a prototype.” I already had a piece of paper prepared: “You approve of us going $250,000 over-budget to prove that this can work.” And finally, after heated yelling and screaming, they signed the piece of paper and kicked us in the ass as we left the room.

It must be said here that Garriott is generally not one to let an overly fussy allegiance to pedantic truth get in the way of a good story. Thus I suspect that the decision to green-light a Multima prototype may not have been arrived at in quite so dramatic a fashion as the tale above. (Garriott has in fact told a number of versions of the story over the years; in another of them, he’s alone in Larry Probst’s office, hectoring him one-and-one into signing the note granting him $250,000 to investigate the possibility.) Most important for our purposes, however, is that the decision was definitely made by early 1995.

The answer to another question is even more murky: that of just when the change was made from an Ultima that you could play online with a few of your buddies — a feature that would be seen well before the end of the 1990s in a number of otherwise more conceptually conventional CRPGs, such as Diablo and Baldur’s Gate — to a persistent virtual Britannia inhabited by dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of other players. The acronym by which we refer to such worlds today would be coined by Richard Garriott in 1997: the “massively multiplayer online role-playing game,” or MMORPG. (And you thought POMG was a mouthful!) Yet it appears that Multima may not have become an MMORPG in the minds of its creators until after Garriott secured his funding, and that that hugely important conceptual shift may not have originated with Garriott himself. One alternative candidate is the man to whom Garriott turned to become the nuts-and-bolts administrator of the project: Starr Long, a quality-assurance lead who had been one of his few Multima allies inside the company for quite some time. (“The original idea,” Long said in a 1996 interview — i.e., close to the events in question — “was to take an Ultima and just make it so you could have a party of people travel together.”) A third candidate is Rick Delashmit, the first and for a long time the only programmer assigned to the project, who unlike Garriott and Long had deep connections to the MUD scene, gaming’s closest extant equivalent to what Multima would become. In fact, Delashmit had actually co-founded a MUD of his own: LegendMUD, which was still running on a single 80486-based personal computer humming away under a desk in an Austin data center.

Regardless of who decided to do what, Long and Delashmit soon had cause to wonder whether signing onto Multima had been their worst career move ever. “We were kind of the bastard stepchild,” Long says. “No one got it and no one was really interested, because everyone wanted to build the next [single-player] Ultima or Wing Commander. Those were the sexy projects.” They found themselves relegated to the fifth floor of Origin’s Austin, Texas, headquarters, jammed into one corner of a space that was mostly being leased out to an unaffiliated advertising agency.

Making the best of it, Long and Delashmit hacked together a sort of prototype of a prototype. Stealing a trick and possibly some code from the last attempt at a Multima, they started with the now-archaic Ultima VI engine. “All you could do was run around and pick up a single object off of the ground,” says Long. “And then if another player ran into you, you would drop it. We had a scavenger hunt, where we hid a few objects around the map and then let the whole company loose to find them. Whoever was still holding them after an hour won.”

It was a start, but it still left a million questions unanswered. A game like this one — or rather a virtual world — must have a fundamentally different structure than a single-player Ultima, even for that matter than the tabletop RPG sessions that had inspired Richard Garriott’s most famous creations. Those games had all been predicated on you — or at most on you and a few of your best mates — being the unchallenged heroes of the piece, the sun around which everything else orbited. But you couldn’t fill an entire world with such heroes; somebody had to accept supporting roles. Some might even have to play evil rather than virtuous characters, upending the core message of Ultima since Ultima IV.

Garriott, Long, and Delashmit weren’t the only ones pondering these questions. In a 1993 issue of Sierra On-Line’s newsletter InterAction, that company’s head Ken Williams — a man who bore some surface similarities to Garriott, being another industry old-timer who had given up the details of game development for the big-picture view by this point in his career — asked how massively multi-player adventuring could possibly be made to function. He had good reason to ask: his own company’s Sierra Network was doing pioneering work in multiplayer gaming at the time, albeit as a closed dial-up service rather than on the open Internet.

I think a multiplayer adventure game is the next major step. Imagine a version of Police Quest, looking like it does now, except that your partner in the patrol car and the people in the street around you are real people. I think this would be cool.

For three months, Roberta [Williams, Ken’s wife], Chris [Williams, the couple’s son], and I have been arguing over how this would work. The problem is that most adventure games have some central quest story. Generally speaking, once you’ve solved the quest the game is over. You are there as the central character, and all of the other characters are there primarily to help move you towards completing your quest (or to get in your way).

A multiplayer adventure game would be a completely different animal. If 500 people were playing multiplayer King’s Quest at the same time, would there have to be 500 separate quests? There are also problems having to do with the fact that people aren’t always connected to the network. If my goal is to save you from an evil wizard, what do I do if neither you nor the evil wizard happen to sign on?

Here’s the thoughts we’ve had so far. What if we create a world that just contains nothing but forest as far as you can see? When you enter the game, you can do things like explore, or even build yourself a house. There’ll be stores where you can buy supplies. Soon, cities will form. People may want to build walls around their cities. Cities may want to bargain with each other for food. Or, for protection against common enemies. There needs to be some sense of purpose to the game. What if, after some amount of time in the land, the game “promotes” you to some status where your goals become to create the problems which affect the city, such as plagues, war, rampaging dragons, etc. In other words, some of the players are solving quests while others are creating them. Sooner or later, it becomes your turn to complicate the lives of others.

Either this is a remarkable case of parallel invention or someone was whispering in Ken Williams’s ear about MUDs. For the last paragraph above is an uncannily accurate description of how many of the latter were run, right down to dedicated and accomplished players being elevated to “wizard” status, with powers over the very nature of the virtual world itself. The general MUD design philosophy, which had been thoroughly tested and proven solid over the years, held that the creators of multiplayer worlds didn’t have to worry overmuch about the stories and quests and goals that were needed for compelling single-player games. It was enough simply to put a bunch of people together in an environment that contained the raw building blocks of such things. They’d do the rest for themselves; they’d find their own ways to have fun.

In our next article, we’ll see what resulted from Ken Williams’s ideas about massively-multiplayer adventure. For now, though, let us return to our friends at Origin Systems and find out how they attempted to resolve the quandary of what people should actually be doing in their virtual world.

In the immediate aftermath of that first online scavenger hunt, nobody there knew precisely what they ought to do next. It was at this point that Rick Delashmit offered up the best idea anyone had yet had. Multima would share many commonalities with textual MUDs, he said. So why not hire some more folks who knew those virtual worlds really, really well to help the Origin folks make theirs? He had two friends in mind in particular: a young couple named Raph and Kristen Koster, who had taken over the running of LegendMUD after he had stepped down.

The Kosters were graduate students in Alabama, meaning that much of the negotiation had to be conducted by telephone and computer. Raph was finishing up his program in poetry at the University of Alabama, while Kristen studied economics — a perfect pair of perspectives from which to tackle the art and science of building a new virtual world, as it happened. Raph Koster:

We started to get interview questions remotely as they worked to figure out whether we were qualified. All of the questions came from what was very much a single-player slant. We were sent examples of code and asked if we could write code like that and find the bugs that had been intentionally inserted into the code. It was something like a misplaced closing brace.

Finally, we were asked for a sample quest. I sent them the entire code and text of my quest for the Beowulf zone in LegendMUD, but then also said, “But we wouldn’t do quests this way at all now.” Kristen and I had been working on a simulation system based on artificial life and economic theory. We basically sent in a description of our design work on that. It was a system that was supposed to simulate the behavior of creatures and NPCs [non-player characters] using a simplistic version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, with abstract properties behind everything.

The Kosters were hired already in the spring of 1995, but couldn’t start on a full-time basis until September 1. Over the course of several drives between Tuscaloosa and Austin and back in the interim, they hashed out their vision for Multima.

They wanted to lean heavily into simulation, trusting that, if they did it right, quests and all the rest would arise organically from the state of the world rather than needing to be hard-coded. Objects in the world would be bundles of abstract qualities which interacted with one another in pre-defined ways; take an object with the quality of “wood” and touch it to one with the quality of “fire,” and exactly what you expected to happen would occur. This reliance on qualities would make it quick and easy for people — designers or just ordinary players — to create new objects on the fly and have them act believably.

But the system could go much further. The non-player creatures which populated the world would have different sorts of qualities attached, derived, as Raph Koster notes above, from Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Each creature would have its own types of Food and Shelter that it sought to attain and retain, alongside a more elevated set of Desires to pursue and Aversions to avoid once it had served for its most basic needs.

An early preview of the game, written by Paul Schuytema for Computer Gaming World magazine, describes how the system would ideally work in action, how it would obviate the need for a human designer to generate thousands of set-piece quests to keep players busy.

Designing a dynamic world is a tricky business. How do you create enough quests to interest 2000 people? Origin’s solution: don’t. Create a world with enough logical conditions that it will generate its own quests. For example, consider a cave in the virtual world. Any self-respecting cave needs a monster, so you assign the cave a “need for monster” request of the game-world engine. Poof! A monster, let’s say a dragon, is then spontaneously created in the cave. Dragons are big eaters, so the dragon sends out a “need for meat” request. Meat, in the form of deer, roams the forest outside the cave, so the dragon’s life consists of leaving the cave to consume deer. If something happens that lowers the deer population (bad weather, over-hunting, or a game administrator strategically killing off deer), the dragon will have to widen its search for meat, which might lead it to the sheep pastures outside town.

At this point, NPCs can be useful to tell real players about a ravenous dragon roaming the countryside. NPCs can also sweeten the pot by offering rewards to anyone who can slay it. But what are they going to say?

“All of the [NPCs’] conversations come from a dynamic conversation pool which is linked to the world state,” explains Long. This means that if you, as a player, were to walk into this town, any one of the villagers will say something like, “Hey, we need your help. This dragon is eating all our sheep.” Thus, the “Kill the Dragon” quest is underway — succeed, and the villagers will handsomely reward you.

If you put it all together correctly, you would end up with a living world, to an extent that even the most ambitious textual MUDs had barely approached to that point. Everything that was needed to make it a game as well as a virtual space would come about of its own accord once you let real humans start to run around in it and interfere with the lives of the algorithmically guided dragons and guards and shopkeepers. It would be all the more fun for being true to itself, a complex dynamic system responding to itself as well as to thousands of human inputs that were all happening at once, a far cry from the typical single-player Ultima where nothing much happened unless you made it happen. Incidentally but not insignificantly, it would also be a sociologist’s dream, a fascinating study in mass human psychology, perhaps even a laboratory for insights into the evolution of real-world human civilizations.

When they arrived for their first day on the job, the Kosters were rather shocked to find that their new colleagues had already begun to implement the concepts which the couple had informally shared with them during the interview process and afterward. It was disconcerting on the one hand — “It freaked us out because we had assumed there was already a game design,” says Raph — but bracing on the other. This pair of unproven industry neophytes, with little on their résumés in games beyond hobbyist experimentation in the obscure culture of MUDs, was in a position to decide exactly what Multima would become. It would take a year or more for Raph Koster to be given the official title of “Creative Lead”; when he arrived, that title belonged to one Andrew Morris, a veteran of Ultima VII and VIII who had recently been transferred to the project, where he would struggle, like so many others at Origin, to wrap his head around the paradigm shift from single-player to multiplayer gaming. But for all intents and purposes, Raph and Kristen Koster filled that role from the start. Each was paid $25,000 per year for building this brave new world. They wouldn’t have traded it for a job that paid ten times the salary. At their urging, Origin hired several other MUDders to work with them on what was now to be called Ultima On-Line; the game would soon loose the hyphen to arrive at its final name.

I can’t emphasize enough what a leap into uncharted territory this was for Origin, as indeed it would have been for any other games studio of the time. To put matters in perspective, consider that Origin began working on Ultima Online before it even had a static website up on the Internet. The company had always been in the business of making packaged goods, games on disc that were sold once for a one-time price. Barring a patch or two in the worst cases, these games’ developers could wash their hands of them and move on once they were finished. But Ultima Online was to be something entirely different, a “game” — if that word even still applied — that was run as a service. How should people pay for the privilege of playing it? (Origin had no experience with billing its customers monthly.) And how much should they pay? (While everyone on the team could agree that Ultima Online needed to be appreciably cheaper than the games on CompuServe and its ilk, no one could say for sure where the sweet spot lay.) In short, the practical logistics of Ultima Online would have been a major challenge even if the core team of less than a dozen mostly green youngsters — median age about 22 — hadn’t also been trying to create a new world out of whole cloth, with only partially applicable precedents.

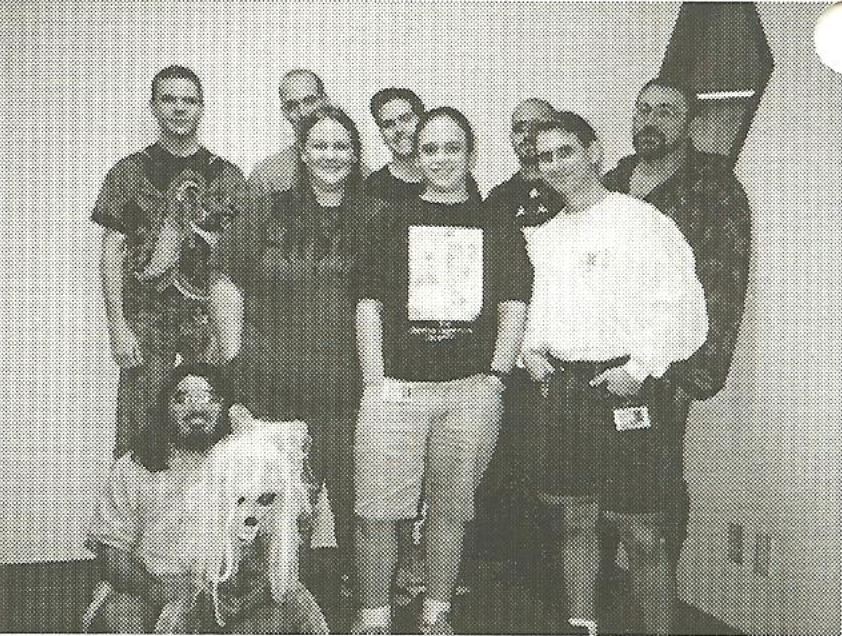

The early Multima team, or the “MUDders of Invention,” as they sometimes liked to call themselves. Clockwise from top left: Rick Delashmit, Edmond Mainfelder, Clay Hoffman, Starr Long, Micael Priest, Andrew Morris, Scott Phillips, Kristen Koster, and Raph Koster.

When the advertising agency that had been the team’s neighbor moved out, Origin decided to gut the now almost empty fifth floor where the latter was still ensconced. “They literally knocked out all the walls and the windows,” says Raph Koster. “So, the elevator surfaced to bare concrete. If you turned right, you went to see our team in a converted hallway, the only part left standing. If you turned left, you fell five floors to your death.” It was freezing cold up there in the winter, and the dust was thick in the air all year round, such that they learned to wrap their computers in plastic when they left for the day. “This team was given the least possible support you can imagine,” says Richard Garriott.

Undaunted, the little group did what the best game developers have always done when cast onto uncharted waters: they made something to start with, then tested it, then iterated, then tested some more, ad nauseum. Garriott came by “once a month or so,” in the recollection of Raph Koster, to observe and comment on their progress. Otherwise, their ostensible colleagues at Origin seemed hardly to know that they existed. “We were punk kids doing stuff in the attic,” says Raph, “and our parents had no idea what we were up to.”

In January of 1996, they put a message up on the Origin Systems website (yes, one had been built by this point): “Ultima Online (working title, subject to change) is now taking applications from people interested in play-testing a pre-alpha version, starting on March 1, 1996.” Almost 1500 people asked to take part in a test which only had space for a few dozen.

The test began a month behind schedule, but it proved that the core technology could work when it was finally run from April 1 until April 8. “This will be damn awesome when it comes!” enthused one breathless participant over chat. Richard Garriott thrilled the group by appearing in the world as his alter ego one evening. “We ran into LB! The REAL THING!” crowed a starstruck tester. “So what? I went adventuring with him to kill monsters!” scoffed another.

A more ambitious alpha test began about a month later, with participants logging in from as far away as Brazil and Taiwan. The developers waited with bated breath to see what they would do in this latest, far more feature-complete version of the virtual world. What they actually did do was an eye-opener, an early warning about some of the problems that would continue to dog the game and eventually, in the estimation of Raph Koster, cost it half its user base. Koster:

On the very first day of the alpha, players appeared in the tavern in Britain [the capital city of Ultima’s world of Britannia]. They waited for other newbies to walk out the doors, then they stood at the windows and shot arrows at them until they died. The newbies couldn’t shoot back because the archers were hidden behind the wall inside the building. This is, of course, exactly what archery slits were invented for, but it made for a truly lousy first impression of the game.

That was the first time that players took something inherent in the simulation and turned it against their fellow players. Not long after, someone spelled out “fuck” on the main bridge into Britain using fish. Not long after that, players figured out that explosive potions detonated other potions. It was illegal to kill someone in town; it would get you instantly killed by the guards. But if you ran a chain of potions a long distance, like a fuse, you could avoid that.

Chalk it up as another lesson, one to which the team perhaps should have paid more attention. The hope was always that the community would learn to police itself much like those of the real world, that the risks and the stigma of being a troublemaker would come to outweigh the gains and the jollies for all but the most hardened members of the criminal element. Richard Garriott seems to have been in an unusually candid mood when he expressed the hope in a contemporary interview:

One of the unfortunate side effects of computer gaming is that we have a whole generation of kids who have no social graces whatsoever. And this is exemplified in my mind by how much I hate going online for discussions I am invited to do once a month or so. And I truly abhor going to do that for a variety of reasons, one because it’s such a slow experience, but also because everyone has a level of anonymity behind their online persona, [and] they lose their normal and proper etiquette. So you have people screaming over each other to get their questions in, people screaming expletives, people popping in a chat room and making some dumb comment and then popping out again — the kind of behavior that you would never get away with in the real world. So one of the things that I’m really keen to introduce with Ultima Online is making people responsible for their actions, and this will happen as people are recognized by their online persona within the game. They won’t be so anonymous anymore.

This hope would be imperfectly realized at best. “I used to think that you could reform bad apples and argue with hard cases,” says an older and presumably wiser Raph Koster. “I’m more cynical these days.”

So, the alpha testers ran around breaking stuff and making stuff, while the gods of the new fantasy world watched closely from their perch on a gutted floor of an anonymous-looking office building in flesh-and-blood late-twentieth-century Texas to see what it was they had wrought. A bug in the game caused killed characters to respawn naked. (No, not even these simulation-committed developers were cruel enough to make death permanent…) Some players decided they liked it that way, leading to much of Britannia looking like a nudist colony. The guards in the cities had to be instructed to crack down on these victimless criminals as well as thieves and murderers.

But the most important finding was that most of the players loved it. All of it. “We had people who literally did not log off for a week,” says Starr Long. “Groups of players formed tribes, and at the end of the test there was a huge battle between the two largest tribes. None of that we set up. We gave them the world to play in, and human nature took over.” From one of the first substantial previews of the work-in-progress, published in Next Generation magazine:

In a very real sense, the world is what you make of it. One of the more interesting results of Ultima’s alpha testing is that when you have several hundred people in one place at one time, they tend to form their own micro-societies. There are already some two dozen player-created “guilds.” For example, when Richard Garriott signed on as his alter-ego Lord British, two groups sprang up: the Dragon Liberation Front, which pledged itself to destroying him, and the aptly named Protectors of Virtue & Lord British. Threats were made, battles were joined, and a fine time was had by all.

Just as gratifyingly, reports of the alpha test, in the form of previews like the above in many of the glossy gaming magazines, were received very positively by ordinary gamers who hadn’t known that a massively multiplayer Ultima was in the offing prior to this point. Some went so far as to form and run guilds through email, so that they would be ready to go when the day came that they could actually log in. There was still much work to be done before Ultima Online would be ready to welcome the unwashed masses inside, but the MUDders who were making it believed that all of the arrows were pointing in the right direction.

Until, that is, September 27, 1996, when it suddenly seemed that its thunder might have been well and truly stolen. On that date, The 3DO Company published something called Meridian 59, which purported to already be what Ultima Online intended to be: a massively-multiplayer persistent virtual fantasy world. Its box copy trumpeted that hundreds of people would be able to adventure together at the same time, killing monsters and occasionally each other, whilst also chatting and socializing. It sounded great — or terrible, if you happened to be working on Ultima Online.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: the books Braving Britannia: Tales of Life, Love, and Adventure in Ultima Online by Wes Locher, Postmortems: Selected Essays, Volume One by Raph Koster, Online Game Pioneers at Work by Morgan Ramsay, Through the Moongate, Part II by Andrea Contato, Explore/Create by Richard Garriott, and MMOs from the Inside Out by Richard Bartle; Questbusters of July 1987; Sierra’s customer newsletter InterAction of Summer 1993; Computer Gaming World of October 1995 and October 1996; Starlog of December 1983; PC Powerplay of November 1996; Next Generation of June 1996, September 1996, and March 1997; Origin’s internal newsletter Point of Origin of November 3 1995, January 12 1996, and April 5 1996.

Web sources include a 2018 Game Developers Conference talk by some of the Ultima Online principals, an Ultima Online timeline at UOGuide, and some details about LegendMUD, the winner of MUD Connector‘s coveted “MUD of the Month” prize for October 1995.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Not the same game as the 2002 Bioware CRPG of the same name. |

|---|

Sniffnoy

February 2, 2024 at 6:34 pm

Typospotting: You have “baited breath” for “bated breath”.

Jimmy Maher

February 2, 2024 at 6:46 pm

Thanks!

Jason Lefkowitz

February 2, 2024 at 7:27 pm

It’s Raph (short for “Raphael”) Koster, not Ralph.

https://www.raphkoster.com/about-raph/cv/press-kit/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raph_Koster

Jimmy Maher

February 2, 2024 at 7:33 pm

Ouch. I kept double-checking the spelling of Kristen Koster’s name, and overlooked this. Thanks!

VV

February 3, 2024 at 9:21 am

“uses and minuses”?

Also thanks for great article (as always).

Jimmy Maher

February 3, 2024 at 9:25 am

Misuses, not minuses. ;)

Manyleeks

February 3, 2024 at 7:01 pm

Fascinating article as always. It’s difficult to put in context now, in a post World of Warcraft world, how utterly unprecedented UO was at the time – I am looking forward to the next article!

I used to play MUDs in the late 90s / early 00s, although by that stage they were already well past their glory days and it was unusual to see more than 10-15 people at a time on even the larger MUDs. Griefing was definitely a problem at that time, even in the relatively limited textual environment and with a smaller playerbase. It’s quaint that Garriott thought at the time that having persistent characters would resolve the issue…

IJMC

February 4, 2024 at 12:09 am

The effort to model all creatures’ needs to design a self-fulfilling, self-interacting worlds reminds me of an earlier effort we heard about over a decade ago:

https://www.filfre.net/2012/11/the-hobbit/

I look forward to learning whether UO came closer to realizing their ambitions!

Hadean

February 4, 2024 at 5:28 am

I was a big fan of MUDs (and especially MOOs), AND Ultima, so when Ultima Online asked for alpha and beta testers, I couldn’t resist. Loved every second of it, though I never actually bought the game or played the commercial version. I knew, during the beta in particular, that an addiction was lurking around the corner. Considering what happened to friends playing UO, and especially World of Warcraft, I think I might have saved myself a world of hurt.

(I also beta tested for Microsoft Windows 95/98/ME, and man those two pieces of software did not get along).

In any case, reading the history behind all of it is absolutely wonderful – thanks!

Jimmy Maher

February 4, 2024 at 9:20 am

Yes, that’s the other side of this, isn’t it? Virtual worlds are fascinating to look into from outside, but are they really good for the people who spend dozens of hours per week in them?

Ross

February 5, 2024 at 1:47 pm

Concerns about the health, safety, and morality of virtual worlds for the people who spend time in them hardly ever start out from a point of honest comparison with the health, safety, and morality of the real world for the people who spend time in it.

(That is, all too often, moral panic over virtual worlds meanders close to “The actual problem is that it is letting losers get some joy out of life, rather than letting the crushing misery of the real world, I dunno, I guess inspire them to become more socially acceptable? Except we don’t actually care about that; we’re just mad that they found a way to escape the system”)

Jimmy Maher

February 5, 2024 at 2:36 pm

I’m sorry, my friend, but gaming addiction is a significant social problem, which negatively affects the mental and physical health, real-world relationships, finances, and educational and employment prospects of millions of people. It just is. I’ll give you concerns over violence in games as a “moral panic,” since the evidence there is inconclusive at best. But the evidence about general gaming addiction is overwhelming.

Obviously, the majority of people who have played Ultima Online, Everquest, World of Warcraft, or any of the other MMORPGs have been able to enjoy them strictly as free-time entertainments. But some number of players — probably higher than the numbers associated with other types of gaming — have gone to an unhealthy extreme. And this is part of the MMORPG story as well. It’s certainly not the main thrust of this series, but it’s worth mentioning at some point, I think.

Ross

February 6, 2024 at 7:11 pm

I certainly didn’t mean to imply that gaming addiction wasn’t real; only that the public response, like the response to most forms of addiction, is hopelessly entangled with a kind of puritanism, and that in particular, any public discourse even when claiming to focus on health concerns, more often blatantly ignore the health aspects in favor of the common moralizing meme that anything out-groups do to comfort themselves is immoral, because misery is their lot (See also drugs, homelessness, immigration, or go back to the ninteenth century and look at the moral panic against the 40-hour work week)

Captain Rufus

February 4, 2024 at 10:12 am

Good old UO. A game where I got player killed within minutes of my first login. Before I had even discovered how to move.

Ultima? More like Grand Theft Sosaria really. Open pvp basically killed the game’s long term appeal and the world simulation system made things utterly miserable until 2nd Age came out.

Then it was interesting because OMG ONLINE ULTIMA.

Then Renaissance made all the wolves have to hunt each other and they stopped having fun since now they had to fight people who could and were prepared to fight back, many realizing they in fact were just bullies looking for safe targets to harass. This was probably the best time for UO but by then EverQuest with its built in pvp flag and 3d graphics had won out in spite of mechanically being worse than UO and Asherons Call. Except it was also the most traditional RPG Fantasy that is the bane of every tabletop gamer not wanting generic fantasy Murderhobo.

Thus EQ won the war until WoW had better graphics gameplay and was far less abusive to players. Kind of like the Ultima to EQs Wizardry. (There would be a Wizardry MMO. It’s difficulty and abusiveness killed it very quickly at least in the Western world.)

Though I was already on the back foot just getting UO as game stores were already beginning even in 1997 with the pre order nonsense.

I quite remember calling one of the mall game stores, Electronics Boutique I believe. I asked the person picking up if they had the game in. They asked if I had pre ordered. I responded no. She replied “Then we don’t have any” and hung up on me.

Yeah. Yeah.

Sniffnoy

February 4, 2024 at 6:41 pm

Btw, did anyone else initially think the part about the 5-story drop was a joke about the design of old adventure games? :P

Feldspar

February 6, 2024 at 5:08 am

Origin comes off like a pretty hazardous working environment between that and the metal plate that fell and almost killed Lord British.

James Henderson

February 16, 2024 at 4:33 am

Not to mention all the dust that was in the air, evidently. I can’t say we’d have MMO’s today if it were up to me to work in those conditions. One of the many reasons I’m not cut out for game design, I suppose…

Ralph Unger

February 4, 2024 at 7:38 pm

Roberta [Williams, Ken’s wife] Parenthesis oops.

Ralph Unger

February 4, 2024 at 7:42 pm

Oops, I see that it is a quote. :-)

Alex

February 5, 2024 at 11:56 am

@ Jimmy Maher: I spend some time reading up on Internet/Multiplayer addiction out of personal interest a few years ago. What I found was so depressing, both on players and on developers site that I had to stop. It’s a top that can be really hard to stomach.

Adolfo Tognetti

February 7, 2024 at 6:25 pm

I think “Meridan 59” should be “Meridian 59”.

Really good article as always!

Jimmy Maher

February 7, 2024 at 6:35 pm

Thanks!