This early advertisement for Fallout makes a not-so-subtle dig at gaming’s then-current flavor of the month, the highly streamlined — or, in the view of some, dumbed-down — CRPG Diablo.

Those of you who are regular readers of these histories will surely have noticed the relative dearth of coverage of the CRPG genre over the last few years. This isn’t reflective of any big shift in editorial policy; it’s rather reflective of the fortunes of the genre itself, which were not particularly good in the mid-1990s. Let’s take a moment to review how the CRPG found itself on the outside looking in while the rest of the games industry was growing by leaps and bounds.

The early efforts of pioneers like Jon Freeman, Richard Garriott, Robert Woodhead, and Andrew Greenberg culminated in the CRPG’s commercial breakout in 1985. That year Ultima IV and The Bard’s Tale, conveying two very different but equally tempting visions of what the genre could do and be, both became major hits. CRPGs continued on a steady upward trajectory thereafter, with ever more of them being released. Another watershed was reached in 1988, when Pool of Radiance, the first full-fledged, licensed implementation of the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop rules on computers, sold over 250,000 copies to become the most successful game ever published by SSI, heretofore a modest purveyor of computerized wargames. More CRPGs came thick and fast after that.

By 1992, however, CRPGs were beginning to seem like too much of a single, fairly homogeneous thing. Dungeons & Dragons, Tunnels & Trolls, Might and Magic, The Magic Candle… even when the games were made with passion and love, which for the most part they were, they were becoming a bit difficult for even the cognoscenti to distinguish from one another. With their intense focus on statistics and their usually turn-based combat systems, these games seemed increasingly out of touch with the broader trends in gaming, whether one spoke of the flashy multimedia presentation of interactive movies or the visceral action of DOOM and its contemporaries.

The genre tried to adapt to the changing times by streamlining itself, replacing turn-based with real-time combat systems and making more use of multimedia. A couple of these “CRPG Lites” met with some success; Westwood’s Lands of Lore and Interplay’s Stonekeep both managed to sell more copies in the expanded marketplace of the mid-1990s than Pool of Radiance had at the end of the previous decade. But they were the exceptions that proved the rule. CRPGs stopped appearing regularly on the bestseller charts. As a result, most American publishers washed their hands of the genre entirely, leaving it to European importers and boutique diehards like SSI, who continued to flood the market with ever more underwhelming Dungeons & Dragons product until TSR, the maker of the tabletop game, finally took their license to do so away.

And then, just as 1996 was turning into 1997, along came a little game called Diablo, from Blizzard Entertainment. It did streamlining right; it took the traditional attributes of the CRPG, simplified them enough to make them intuitively understandable without ever cracking open a manual, polished the living hell out of every facet of their presentation and implementation, and then added the secret sauce of procedural generation to yield a game that was, in theory at least, infinitely replayable. In fact, Diablo was so streamlined that gamers have continued to argue to this day over whether it ought to qualify as a “real” CRPG at all. Yet its fast-paced accessibility and addictive nature made it a mainstream hit on a scale which no earlier CRPG could touch. In thus demonstrating to the world that there was some life yet in the old paradigm of exploring dungeons, killing monsters, collecting loot, and leveling up your character, it provided the first glimmer of a CRPG Renaissance that was lurking just over the horizon.

At the time, though, there was ample reason to wonder whether the Diablo model was all that the genre could aspire to in the future. What about the more conceptually ambitious CRPGs of yore, the ones that had striven to be about more than just loot and stats, that had often attempted — to be sure, sometimes clumsily — to present real interactive stories, set in compelling, internally consistent worlds? Those whom Diablo left still wishing for those things had their wish granted ten months later, by a more full-faceted herald of the CRPG Renaissance that went by the name of Fallout.

In 1990, Tim Cain was a graduate student at the University of California, Irvine. He was studying computer science, but his first love had long been games, both on the tabletop and on the computer. Late that year, his father passed away while still in his fifties, prompting the young man to properly confront life’s brevity and unpredictability for the first time. Determined to rededicate his own life to that which he loved most, he bought himself the latest issue of Computer Gaming World and sent his résumé out to every corporate address he could find within its pages. He wound up being called in to an interview at and then receiving an offer from Interplay Productions, which happened to be located conveniently nearby in Southern California. His first project as a programmer for Interplay was The Bard’s Tale Construction Set; his second was Rags to Riches: The Financial Market Simulation. After finishing the latter, Cain worked mainly on installers and other unglamorous utilities, whilst tinkering with game engines of his own devising, waiting for a chance to make his mark as not just a programmer but a creative voice. In early 1994, when Interplay’s founder and CEO Brian Fargo said that he was interested in licensing a tabletop RPG property for adaption into a computer game, Cain thought he saw his chance.

An avid tabletop role-player since childhood, Cain had in recent years become a devotee of a system called GURPS, owned by the Austin, Texas-based outfit Steve Jackson Games.[1]This American Steve Jackson is not the same man as the British Steve Jackson, the co-founder of Games Workshop. GURPS — the acronym stands for “Generic Universal Role-Playing System” — was a prominent member of a new guard of tabletop RPGs that aimed to be more flexible and player-empowering than Dungeons & Dragons, that hoary old standard bearer of the field. Instead of relying upon rigid class archetypes during character creation, it let players select from a menu of skills, advantages, and, most interestingly, disadvantages that made each character completely unique. For example, a disadvantage might be something as simple as an inability to tell even the smallest white lie — a disconcertingly hard quality to live with, whether in our world or any of its more fantastic counterparts that were to be found in GURPS source books. Speaking of which: you could use the basic GURPS rules for Dungeons & Dragons-style fantasy, but you could also use them for space opera, cyberpunk, Westerns, horror, mysteries… you name it, as long as you either bought the right supplements from Steve Jackson or were willing to put in the effort to roll your own rules extensions.

Tim Cain loved GURPS so much that he programmed several digital utilities to make the job of a GURPS game master easier and uploaded them to the Internet. He brought his obsession with him to Interplay and spread it among the employees there; within a year or so of his arrival, three separate GURPS campaigns were going on around the office. So, when Brian Fargo sent his memo asking for suggestions of tabletop properties to license, many more voices than Cain’s alone shouted “GURPS!” in unison. Fargo was happy enough to oblige his people. Within weeks, he had signed a contract with Steve Jackson to make a GURPS-branded computer game, with more to follow if the first was successful. The contract didn’t specify which of GURPS’s many incarnations the game in question would embrace. Initially, everyone seemed to assume it would be high fantasy, just like 90 percent of its peers in the CRPG space.

A certain fuzziness about labels and boundaries was rather endemic to Interplay during this period. The company’s ticket to the big leagues had been The Bard’s Tale back in 1985, and Fargo had rushed to follow that masterstroke up with sequels and other CRPGs later in the decade. Yet he was too ambitious a businessman to be confined to one genre. By the early 1990s, Interplay had settled firmly into the spaghetti approach to game developing and publishing: throw a little bit of everything at the wall and see what sticks. Sometimes they hit the bull’s eye — as they did with the gimmicky but fun Battle Chess, the Medieval builder Castles, their licensed Star Trek adventure games, and the frenetic shoot-em-up Descent. Fargo also scouted abroad for interesting games, signing contracts to become the American importer of standout European titles like Out of This World and Alone in the Dark. Many of Interplay’s other releases were less impressive and less successful than the aforementioned ones, but the hits sold well enough to make up for the misses.

In most respects, Fargo was as eager to chase the winds of fashion as any of his counterparts in the executives suits of other publishers. Unlike them, though, he retained a sneaking fondness for CRPGs which was grounded in something other than the hard-hearted logic of business. Thus his decision to take a flier on a GURPS game in 1994, in defiance of all of the industry’s prevailing conventional wisdom.

This is not to say that the nascent game was a major priority. Tim Cain was a talented programmer who was currently somewhat under-utilized, who knew and loved GURPS and was champing at the bit to put his creative stamp on a game that he could truly call his own; all of these factors made him a natural choice for the project. But after he was duly assigned to it, he worked all by himself for several months, tinkering with an isometric engine and implementing the GURPs rules piece by piece. In September of 1994, it had still not been decided what the game was actually to be in the most fundamental sense; most people at Interplay still assumed that it would be “generic” fantasy, as befitted the first word of the GURPS acronym.

Desperate to inject some momentum into an assignment that was starting to seem more like a purgatory, Cain decided to host a series of after-hours brainstorming sessions at a local pancake restaurant. Anyone who was interested could join him to eat a meal containing way too much sugar to be healthy, talk about his GURPS engine-in-progress, and bat around ideas for what sort of game it ought to power. Only a handful of people showed up regularly. Luckily, among them were two employees from the art department, Leonard Boyarsky and Jason Anderson, who had more than enough enthusiasm and creativity to go around. The budding power trio’s thinking soon shifted away from epic fantasy, first toward time travel, and then, when that began to seem too daunting, in the direction of a post-apocalyptic scenario. Yes, there was a GURPS source book for that as well.

Brian Fargo was immediately receptive to the idea, as they had anticipated he might be. Back in 1988, when Interplay was still known primarily for their CRPGs, they’d made one called Wasteland, set in the aftermath of a nuclear war. At the time, Interplay had been a development studio only, relying on Electronic Arts to publish their games; in fact, Wasteland had been the very last Interplay game to be published by EA. As was standard practice in the industry, the latter had been given the rights to the Wasteland name, preventing Interplay from ever doing a sequel, even though the first game had sold fairly well. With the slightly messy breakup between Interplay and EA now more than half a decade in the past, Fargo thought he might be able to convince his former publisher to give up the name. He told Cain, Boyarsky, and Anderson that he would try, at any rate. In the meantime, he said, they should get on with making their post-apocalyptic game, which could even in the worst case be marketed as a “spiritual successor” to Wasteland. Just like that, Tim Cain had two full-time colleagues to help him make his GURPS CRPG.

These events occurred in December of 1994. Early in the new year, Leonard Boyarsky came to his two teammates with a proposal whose importance to the game and the trans-media franchise it has spawned can scarcely be overstated. Instead of being present-tense or even conventionally futuristic, Boyarsky mused, what if the world of the game was “what the fifties thought the future would be like?”

In light of this stroke of genius, it was actually for the best that Brian Fargo ultimately failed to convince Electronic Arts to give him back the rights to the Wasteland name. By the time he reported his failure to the team, the new game had long since become its own thing, quite distinct from Wasteland. Ironically, it was Fargo who chose the game’s final name, from a long list of potential appellations given to him by his employees after yet another extended brainstorming session. He knew that the game simply had to be known as Fallout as soon as he saw the name. It was pithy but memorable, and perfectly evoked the game’s cheerily paranoid atmosphere of duck-and-cover drills and atomic cafés.

Every present creates its possible futures in its own image, a fact which is amply demonstrated by “The Gernsbeck Continuum,” one of my favorite William Gibson stories. In it, a 1980s photographer assigned to shoot the decrepit holdover architecture of the mid-century Art Deco era suffers something of a psychotic break. He begins to see “semiotic ghosts” of that lost America everywhere he looks, the same one that some prominent political figures still speak of so longingly today. This lost America “knew nothing of pollution, the finite bounds of fossil fuel, or foreign wars it was possible to lose”; it was all giant Tom Swift airplanes and enormous tail fins, all coruscating chrome and complacent conformity as far as the eye could see. Whether he knew this story or not, Leonard Boyarsky had a similar vision for Fallout, one which Cain and Anderson embraced wholeheartedly to turn the game into an alternate history rather than a tale of nuclear war in the world that we know.

By following the breadcrumbs embedded in the finished game and its sequels, we can deduce that their timeline diverges from ours just after the Second World War — more exactly, in 1947, in which year a team of researchers at Bell Labs failed to invent the transistor in this alternate universe. Coincidentally or relatedly, the postwar era of uninhibited Big American Government that brought such wonders as the Moon landing and the Internet even in our timeline never petered out in this one. Meanwhile the march toward miniaturization that occurred in our timeline once high-tech became the purview of corporations rather than governments failed to occur in this one: no transistor radios, no portable televisions, no personal computers, no Sony Walkmen, no smartphones. Technology continued to grow up rather than grow down, to emphasize the monumental at the expense of the personal. The lack of innovation at the scale of individuals did much to allow the stifling social conformity of the 1950s to persist. Fallout’s version of the 1960s saw no acid rock, no sexual or feminist revolutions, no civil-rights movement and no anti-war movement. Not having to deal with protestors and draft dodgers, the American military was eventually victorious in Vietnam. Nevertheless, the Cold War didn’t end in 1989, in fact went on for 130 years.

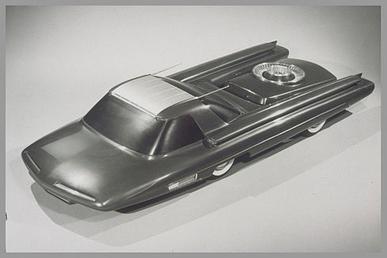

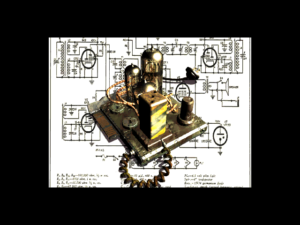

By the end of that span of time, people had nuclear reactors in their homes and cars, alongside robot assistants that were presumably equipped with something like Isaac Asimov’s “positronic brains” rather than microprocessors. The police and military had death rays straight out of Lost in Space. And yet computers were still the hulking monstrosities that one might find in an IBM product brochure from our 1960s.

Fallout’s equivalent of the Nucleon is the Corvega, a car whose trunk-sized nuclear reactor has a disconcerting habit of melting down.

In 2077, China and the West went to war. (The substitution of China for the Soviet Union as the primary antagonist is a melancholy reflection of the times in which Fallout was made, when Russia was still widely expected to join the community of rules-abiding democratic nations — and to become a significant growth market for computer games in the process.) The world was effectively destroyed in the war. The only people who escaped the horrors of radiation exposure in the United States were those who were able to take shelter in one of the hardened, self-sufficient “vaults” that had been scattered around the country for just such an eventuality.

Fallout proper begins in 2161, casting you as a resident of one of these vaults who has been tasked with venturing out into the ruined world in order to locate a chip that is needed to keep your community’s water-purifying facilities functional. Everywhere you go during the game, you encounter the shattered detritus of an era when, as David Halberstam wrote in his book about the 1950s, the good life was defined as “finding a good white-collar job with a large, benevolent company, getting married, having children, and buying a house in the suburbs.” Of course, everything is wildly exaggerated for comedic effect — who could forget Nuka-Cola, or Pip-Boy, the clunkiest handheld PDA ever? — but there’s an unnerving resonance to the setting that you won’t find in The Forgotten Realms of Dungeons & Dragons. It may not be irrelevant to mention here that Tim Cain is himself a gay man — i.e., one of the sorts of people whom 1950s society preferred to pretend did not exist at all. (At the time he made Fallout, he was still closeted, living and working as he did in a hardcore-gamer milieu that was scarcely less prejudiced against people like him than the 1950s writ large had been.)

The Fallout team had grown to thirteen people by January of 1996, with perhaps the most notable additions being Chris Taylor as lead designer and Mark O’Green as dialog writer. Cain’s official title became “producer.” He listened to everyone, but he didn’t hesitate to say no to any proposals that violated the core retro-future vision. Any technology that didn’t look like someone could have dreamed it up in the 1950s got tossed. Ditto any of the lazily anachronistic contemporary-pop-culture references that were so endemic in other games.

But Cain’s vision for this game extended well beyond the boundaries of its fiction. With the impetus of GURPS behind it, it was to be a new type of CRPG in other, even more important ways, ones that would place their stamp on a whole ecosystem of games that would come later. Every bit as much as Diablo, Fallout deserves to go down in history as the urtext of a brand-new strand of the CRPG.

When they first began attempting to transfer the tabletop-RPG experience to computers in the late 1970s and early 1980s, programmers naturally tended to emphasize the things that computers could do well and to de-emphasize those that they could do less satisfactorily. Computers were good at smoothing out all of the lumpy complexities of Dungeons & Dragons combat, with its endless die-rolling, table-consulting, and round-counting, not to mention the arguments that inevitably arose from its hundreds of pages of baroque rules. They were less good, however, at simulating conversations with the people you met, or letting you choose your destiny in any less granular sense than whether to turn right or left at the next intersection in a dungeon. So, most CRPGs spread a thin veneer of story and world-building atop game engines that were really all about combat and logistics; they became “roll-playing” rather than “role-playing” games. (Seen in this light, the bestowal of the Dungeons & Dragons license upon the wargame publisher SSI starts to make a lot more sense…) Those CRPGs that did endeavor to do more with their fictions tended not to do so with much systemic rigorousness. (Ultima VII, for example, although a brilliant game in its way, is at its best when it’s content to be a walking-and-talking simulator.)

Tim Cain and company wanted to move beyond the old dichotomies and simplifications. Wasteland had actually tried to do some of the same things that they wished to do, by using a skill-based system inspired by the tabletop RPG Mercenaries, Spies, and Private Eyes. (Non-fantasy settings did tend to drive designers in that direction, if only to find a use for character attributes like Intelligence that weren’t obviously useful in combat that didn’t involve spell-casting.) But Wasteland had been hobbled by the 8-bit computers on which it ran; in practice, it devolved into a sort of skill and attribute lottery much of the time, forcing you to guess which one might be applicable to any given situation and then to actively “use” it from a menu. The faster processors and bigger memories and hard drives at the disposal of Fallout should allow it to implement a system that touched every aspect of the player’s experience far more organically.

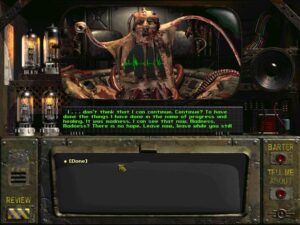

As they were designing each area of Fallout, the team kept three broad character archetypes in mind, which not coincidentally coincide with the three pre-generated starter characters you can choose from in the finished game should you not wish to build one of your own. There was the brawler, who could be expected to fight his way through the game much as one did in the CRPGs of yore; the sneaker, who would solve problems using stealth and thievery; and the diplomat, who would rely on a sharp mind and a silver tongue to bend others to his will. Another of Tim Cain’s non-negotiable requirements was that every character you might make had to have a viable path forward in every situation. Ideally, this would make the character you controlled a reflection of you the player — or at least of the type of person you felt like play-acting as that day — rather than becoming an exercise in purely tactical min-maxing. (This does not mean that plenty of Fallout players haven’t indulged in plenty of min-maxing over the years…) The approach extended right to the climax of the game, where a sufficiently clever diplomat can convince the big villain to give up his nefarious schemes and commit suicide using nothing more than words.

Every aspect of Fallout is tailored to the person you happen to be playing. For example, if you’re a smart cookie, your dialog options reflect this. Ditto if you’re not so smart; Cain decided that anyone with an Intelligence below a certain threshold should be allowed to speak only in single-syllable words. The same general principle holds true when trying to operate or repair machinery, heal your wounds, duck into the shadows… you name it. At the time, no other CRPG had ever implemented such a comprehensive set of rules, to simulate all of your possible interactions with the world.

Then, too, within the framework of affordances and limitations of the character you chose to play, the designers strove to give you maximal freedom of choice at every juncture. You can lay waste to everyone and everything you encounter and still win the game. Or you can try to do as little killing as possible. When the game is over, you’re shown a closing movie that varies on the basis of the choices you made. “I wanted the player to know, ‘We saw you do that, and the game’s going to react to you,'” says Tim Cain. It’s the same ideology that Gabe Newell instilled into the team at Valve that was making the very different game of Half-Life at the same time, an insistence that the virtual world must acknowledge the things you do and respond to them, in order to ensure that your experience is truly your own. Fallout is not especially long by CRPG standards — you can play through it in about 25 hours — but it was explicitly designed to foster replays in radically divergent styles.

Given how intimately linked Fallout was to GURPS in spirit and systems alike, a series of events in February of 1997 ought to have been deadly to its conception of itself. That month Interplay sent Steve Jackson, who hadn’t been following the game’s progression at all closely, a demo of the work-in-progress. It opened with a now-iconic cutscene, in which a soldier shoots a civilian prisoner in the head to the soothing tones of the Ink Spots singing “Maybe.” Jackson took immediate umbrage. At first glance, it’s hard to understand exactly why. While the scene certainly had its fair share of shock value, it’s not as if he was a noted objector to violence in games; one of his company’s signature products was Car Wars, an unabashedly brutal game of Mad Max-style vehicular combat. (“We’re selling a very popular fantasy,” said Jackson to one journalist. “Have you ever been driving down the road and somebody cuts in front of you or otherwise infuriates you to the point where the thought flashes through your mind, ‘Now, if this horn button was a machine gun…'”)

It might be helpful to recognize here that, for all that no one could doubt Jackson’s genuine love for games, he was a temperamental individual and an erratic businessman, whose company went through endless cycles of expansions and layoffs over the years. Tabletop designer and writer S. John Ross, who worked with Jackson often in the 1990s and knew him well, told me that he suspected that, on this occasion as on many others he was witness to, Jackson was attempting to paper over a failure to do his homework with bluster: “There’s a lot of reason to suppose that Steve was just trying to cover for dropping the ball on giving the game an honest try, by overstating his reaction to the five minutes he actually spent with it, thus buying himself time to soften his view on that and actually get a view on the game past the intro — a gambit that didn’t pay off.” If this is a correct reading of the case, it was a dramatic misreading by Jackson of the strength of his own negotiating hand, as S. John Ross alludes.

Be that as it may, on February 17, 1997, Steve Jackson turned up in a huff at Interplay’s Southern California offices, only to have Brian Fargo refuse to meet with him at all. Instead he wound up sitting on the other side of a desk from Tim Cain for several uncomfortable hours, reiterating his objections to the opening movie and to a number of other details. Most of his complaints seemed rather trivial if not nonsensical on the face of them; most prominent among them was a bizarre loathing for “Vault Boy,” the mascot of “VaultTec,” a personification of the whistling-past-the-graveyard spirit of the mid-century military-industrial complex. Cain, who quite liked the maligned movie and adored Vault Boy, stated repeatedly that he “wasn’t empowered” to make the changes Jackson demanded. The meeting ended with no resolutions having been reached, and a dissatisfied Jackson flew home. A few days later, Brian Fargo came to Tim Cain with a question: how hard would it be to de-GURPS Fallout?

If Steve Jackson remains something of a black box, it isn’t so hard to follow Fargo’s line of thinking. The buzz that seemed to have been building around GURPs in 1994 had largely dissipated by this point; with a personality as idiosyncratic as this one at its head, Steve Jackson Games seemed congenitally unequipped to be more than a niche publisher. Meanwhile Interplay now had in the works several Dungeons & Dragons-branded CRPGs. (I’ll have much more to say about them later in this series of articles.) Unlike Dungeons & Dragons, the GURPS name on a box seemed unlikely to become a driver of sales in and of itself. What was the point of bending over backward to placate a prickly niche figure like Steve Jackson?

Jackson tried to backpedal when he realized how the winds were blowing, but it was to no avail. He wasn’t inclined to accept Brian Fargo’s assurances that, just because Fallout wasn’t going to be a GURPS game, Interplay couldn’t do one in the future. “What would you do if you were me?” he asked plaintively of a journalist from Computer Gaming World. “I work on it with them for three years, and then they decide not to go with GURPS. Why would I want to go through that again?”

Setting aside the merits or lack thereof of Jackson’s attempt to cast himself as the victim, the really amazing thing about all of this is how quickly the Fallout team managed to move on from GURPS. This was to a large extent thanks to Tim Cain’s modular programming, which allowed the back-end plumbing of the game to be replaced relatively seamlessly without changing the foreground interface and world. In place of GURPS, he implemented a set of tabletop rules that Chris Taylor had been tinkering with in his spare time for more than a decade, jotting them down “on the backs of three-by-five cards, in notebooks, and on scraps of paper.” Once transplanted into Fallout, his system became known as SPECIAL, after the seven core attributes it assigned to each character: Strength, Perception, Endurance, Charisma, Intelligence, Agility, and Luck.

That’s the official story. Having conveyed it to you, I must also note that there remains much in SPECIAL that is suspiciously similar to GURPS. GURPS’s idea of allowing players to select disadvantages as well as advantages for each character as an aid to better role-playing, for example, shows up in SPECIAL in the form of “traits,” character quirks — “Fast Metabolism,” “Night Person,” “Small Framed,” “Good Natured” — that are neither unmitigatedly good nor bad. I haven’t seen the contract that was signed between Steve Jackson Games and Interplay, but I do have to suspect that, had Jackson been a more conventionally businesslike chief executive with deeper pockets, he might have been able to make a lot of trouble for his erstwhile partner in the courts. But he wasn’t, and he didn’t. In rather typical Steve Jackson fashion, he let GURPS’s last, best shot at hitting the big time walk away from him without putting up a fight.

The breakup with GURPS was only the last in a series of small crises that Fallout had to weather over the course of its three-plus-year development cycle. “Nothing against Brian [Fargo] or anybody else at Interplay,” says Leonard Boyarsky, “but at the time, no one really thought much about Fallout. Brian gave us the money and let us do whatever we wanted to do. I don’t think that was [his] intent, but that’s how it ended up.” As Boyarsky hints, this benign neglect gave the game time and space to evolve at its own pace, largely isolated from what was going on around it — when, that is, it wasn’t being actively threatened with cancellation, which happened two or three times over the course of its evolution. Only in the frenzied final few months of the project, leading up to the game’s release in October of 1997, did it become a priority at Interplay. By that time, Diablo had become a sensation among gamers, leading some there to think that there might be some serious commercial potential in a heavier CRPG as well.

Such thinking was more or less borne out by the end results. Although Fallout did not become a hit on anything like the scale of Diablo, it was heralded like the return of a prodigal son by old-timers in the gaming press. “With a compelling plot, challenging and original quests, and, most importantly, a rich emphasis on character development, Fallout is the payoff for long-suffering RPG fans who have seen the genre diluted in recent times by an endless stream of half-baked, buggy, uninspired duds,” wrote Computer Gaming World. The game sold well over 100,000 copies in its first nine months. It was only the beginning of a trend that would give fans of high-concept CRPGs as much reason to smile as Diablo fans in the years to come.

I’ve offered up quite a lot of explicit or implicit praise for Fallout to this point. Sadly, though, I do have to tell you that it also has its fair share of weaknesses in my opinion. In fact, I’m not sure I’ve ever played another game that marries aesthetic slickness and formal innovation with abject clunk to quite the same degree.

When you first fire it up, Fallout finds a way to put both its best and its worst foot forward. It bids you welcome with an opening movie that’s nothing if not striking and memorable, being the same one that Steve Jackson objected to so vehemently. This kind of clashing juxtaposition of tone and content would become a bit of a media cliché in the post-Sopranos Age of the Antihero, but it was still as jarring as it was intended to be in 1997. However you feel about it, you can’t deny that it’s brought off with astonishing deftness and confidence. We’re a long, long way from the tacky babes in chain-mail bikinis of the CRPGs that came before — and, for that matter, plenty of those that came afterward.

Thanks to Interplay’s proximity to Hollywood and the connections Brian Fargo had cultivated there, Fallout is blessed with an extraordinary cast of voice actors to go with its distinctive, self-assured visual aesthetic. Ron Perlman — the beast from Beauty and the Beast — narrates the second stage of the intro. Other voices that turn up later include that of Richard Moll, best known as the simple-minded bailiff of Night Court, and Richard Dean Anderson, who played the ever-inventive protagonist of MacGyver.

Once we click the “New Game” button, we’re dropped into a character-building system that’s visually of a piece with what has come before. Here we can choose to play one of the three pre-generated characters or make one of our own. Doing the latter is unavoidably more complicated, but the game does a pretty good job of explaining itself even to those who refuse to glance at the manual.

So far, so good. Another movie sets up the first part of the plot, telling us that the vault in which we’ve lived all our life has a failing chip in its water purifier. We must venture out into the world to find another one before the old one dies completely, which will happen in 150 days — yes, this game has a time limit, although there will still be plenty to do after we find the replacement chip, what with all the other problems we’re about to uncover on the Outside. For now, though, off we go, walking through the door to our vault for the first time in our life. Behind it we find… an anonymously dull cave system, full of rats and not much else. It’s right here that we’re first confronted with the fact that, despite the fresh new coat of paint Fallout has received, there is still much that is old-school about the game.

There’s a sort of Puritan ethic to many old CRPGs, an insistence that you have to earn the right to eventually have fun by struggling for a few hours as a glorified exterminator, clubbing pissant vermin with first-level characters who are weak as kittens. Fallout doesn’t start you out as woefully unprepared for the world you face as some CRPGs do, but it certainly doesn’t go all-out to welcome you into its world either. After killing or dodging rats in the caves outside your own vault, you travel to another, abandoned vault in in the hope of salvaging a water chip from it. There you encounter… you guessed it, a whole lot more rats. If you complain to them about this slow and dull beginning, Fallout fans will rush to tell you that the game opens up in the course of things and becomes much more interesting. By no means are they wrong about this. But why can’t it grab our interest from the start? It seems to me that games should strive to delight and intrigue us right from beginning all the way to the end. We’ve earned our fun, if that’s the way one wishes to think about it, via all the boring tasks we did earlier in the day before we finally got to sit down in front of our gaming computer.

Alas, other aspects of Fallout are annoying from the start and never really do improve. Its interface is the opposite of intuitive, seeming to be predicated on the philosophy that, if one mouse click is good, five clicks must surely be better. Everything you try to do is more awkward and fiddly than it ought to be. It’s doubly frustrating because so many of the problems could have been fixed so easily. When you try to conduct transactions with bottle caps — this post-apocalyptic world’s equivalent of coinage — you find that you’re inexplicably only allowed to move 999 of them around at a time, meaning you have to go through multiple rounds of the process just to effect a major purchase or sell off a decent-sized pile of loot. Would it have killed the team to add an extra digit or two here? When you come across a new item and rush to your inventory to see what it is and whether you want to equip it, you find that it’s been added to the end of your list of objects carried, meaning you have to rummage your way down through potentially dozens of other items to get to it. Vital messages scroll by in green text in the tiny window at the bottom left without doing anything to draw your attention to them. They’re shockingly easy to miss entirely. No one of these little sources of friction is sufficient to ruin your experience on its own, but they do begin to add up.

Fallout needed to reconcile the free-roaming real-time movement which late-1990s gamers demanded with a set of turn-based combat rules. As we’ll see in future articles in this series, most Renaissance-era CRPGs with aspirations of offering a deeper gameplay experience than Diablo had to negotiate similarly tricky terrain, for which they deployed various solutions. I have to say that I find Fallout’s one of the least satisfying. Whenever nearby enemies notice you, the game automatically switches into turn-based mode, in which every action you take costs some number of action points. When you run out of action points, there’s nothing to be done but click the (too small and weirdly obscure) “Next Turn” button, at which point everyone else gets a turn before control comes back around to you. It makes for painfully slow going in even the most trivial fights. The worst moments are when you find yourself just at the edge of the perception range of a group of enemies, and the game keeps switching spasmodically between its real-time and turn-based modes. It’s enough to convince you to put all of your skill points into Sneak, just to try to avoid the whole mess.

While I’m complaining, let me note as well that I’m not at all fond of time limits in games like this — not even of fairly generous ones, as Fallout’s admittedly is. Nobody enjoys being told that they’ll have to start over because they spent too much time dilly-dallying in a game’s world. There are other, subtler ways to inculcate a sense of drama and urgency.

Of course, all of these judgments are just that: judgment calls on the part of yours truly. You may very well find that those things I call weaknesses are strengths for you. Certainly the original Fallout still has a devoted fan base who continue to swear by it as the purest articulation of a unique vision, even after its name has gone on to spawn a series of vastly more popular, faster-paced games and, most recently, a popular television series. (Who could have imagined such things when Tim Cain first began to tinker with his GURPS CRPG? Surely not him!) As I grow older, I continue to learn over and over that one person’s great game is another’s boredom simulator. If you love Fallout, I’m very happy for you and would never presume to tell you you’re wrong to feel as you do. Please don’t hate me for having more mixed feelings about it. Believe me, no one is sadder than I am that I can’t fall head over heels in love with it.

There’s just one part of Fallout that is, I would argue, objectively broken: the companion system. In the last few months of the game’s development, when it was suddenly looking like it might have real hit potential in the wake of Diablo’s spectacular reception, a dictate came down from Brian Fargo stating that it must be possible to recruit companions to join you in your quest. So, a handful of these recruitable non-player characters were shoehorned in. Their implementation is woefully incomplete. You can’t even trade items with your friends; some players have been reduced to using their pickpocketing skill as a way to get the right equipment into the right hands. But worst of all is combat when companions are involved. Lacking the time to write custom code to control the companions’ behavior, the team employed the same routines that were already being used to control non-recruitable characters. It’s good fun when you’re fighting a bunch of thugs and one of them mows down most of his own people with his Uzi in his eagerness to put some bullets into you. It’s rather less fun when your character is the one taking friendly fire. Circular firing squads abound when playing with companions, such that the wisest policy is probably just to go through the entire game solo. But having to tiptoe through a minefield in order to have a good time, picking and choosing from the opportunities a game offers you, is pretty much the definition of “broken” in game design, not to mention the antithesis of everything Fallout purports to stand for.

Sometimes your companions will box you in in a narrow space and refuse to move. Your options at this point are to go back to an old save or just to shoot their useless asses.

In my perhaps jaundiced eyes, then, Fallout is a piebald creation, combining amazing aesthetics and world-building with game systems that are groundbreaking in the abstract but sometimes excruciating in execution. Mixed results like these are often the fate of games that dare to push in bold new directions and rejigger the matrix of the possible. The immaculate conception is the exception in game design; change more commonly comes in piecemeal, initially imperfect fashion. The CRPGs that would follow Fallout as the Renaissance gathered steam would embrace its strengths, whilst smoothing out many of its rough edges.

Next time, we’ll see how a venerable series from the previous era of CRPGs adapted its old-school approach to the changing times, and was rewarded with another solid hit which demonstrated that the CRPG’s doldrums were fast coming to an end.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: “Fallout and Yesterday’s Impossible Tomorrow” by Joseph A. November, from the book Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History. The books Beneath a Starless Sky: Pillars of Eternity and the Infinity Engine Era of RPGs by David L. Craddock, Designers & Dragons: A History of the Roleplaying Game Industry, Volume 2, by Shannon Appelcline; Burning Chrome by William Gibson; The Fifties by David Halberstam. Computer Gaming World of January 1997, May 1997, and January 1998; Retro Gamer 186; The Austin American Statesman of April 18 1988.

I also made use of the Interplay archive donated by Brian Fargo to the Strong Museum of Play and of Interplay’s 1998 SEC annual report.

My thanks to S. John Ross, who shared with me his memories of Steve Jackson Games and his impressions of its titular founder. And thank you to Felipe Pepe, Zoltan, Busca, and other commenters for pushing me to add some nuance to the discussion of the overall state of the CRPG genre that opens this article.

Most of all, this article owes a debt to Tim Cain’s YouTube channel, which is a consistent, oddly soothing delight that’s become a fixture of my lunch breaks, regardless of whether “Uncle Tim” wants to tell me about games or chocolate. (“Hi, everyone. It’s me, Tim. Today I’m going to talk about…”) I’m sorry that Fallout doesn’t completely do it for me, Tim. I hope I’ll love Arcanum when I get there.

Where to Get It: Fallout is available as a digital purchase at GOG.com.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | This American Steve Jackson is not the same man as the British Steve Jackson, the co-founder of Games Workshop. |

|---|