When a starry-eyed youngster heads off to Hollywood to chase her dreams, one of two fates awaits her: she might become one of the small minority that makes it and becomes a star, or she might end up lumped in with the vast majority that struggle and wait tables (seemingly every waiter in Los Angeles is an aspiring actor) for years to no avail. It’s either “Hooray for Hollywood” or “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” writ large. That’s the conventional wisdom anyway. But there’s actually a third possibility: the life of the working character actor, who picks up work where she can find it in the form of whatever small roles are available that don’t need a star to fill them. Just as every kid who picks up a guitar dreams of playing to stadiums full of screaming fans (and don’t let any indie-rock snob tell you different), it’s probably safe to say that no actor sets out to be such an anonymous cog in the Hollywood system. Yet it’s not a bad way to earn a living in the craft you love if stardom eludes you. I’ve long been fascinated by these folks whose names usually appear in the credits only as the audience is filing out of the theater, these working professionals who earn a solid living under the radar of the Dream Factory by learning their lines, showing up on time, and doing whatever’s asked of them and doing it well. This other side of the acting life is the subject of The Dangerous Animals Club, written by one of these bit players, Stephen Tobolowsky. It makes for a great read.

Other forms of media have their own equivalents to Tobolowsky. The publishing industry, for example, has always had people like Jim Lawrence.

Born in 1918, Lawrence began his writing career in 1941 when he was hired by the Jam Handy Organization as a scriptwriter for military training films. From then until the end of his life in 1994 he wrote for seemingly anyone who would pay him. Lawrence himself would be the last person to claim to be a great writer, but he always churned out copy that was, within the scope of the genres within which he worked, solidly crafted and eminently professional. When the project allowed, he even showed a considerable flair for imagination.

Lawrence wrote a staggering variety of stuff over his more than five decades as a working writer, but his specialty and greatest love was always fast-paced action-adventure stories for the young. In that genre, he wrote for old-time radio dramas like The Green Hornet; wrote Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew mysteries; wrote a James Bond comic strip for the newspapers; wrote a variety of Marvel comics. His oeuvre includes more than 60 novels alone, virtually none of which bore his own name anywhere in its pages. His most bizarre and disreputable assignment was a series of books about Peter Lance, an alien from the planet Tharb who has come to Earth to study this curious human phenomenon of sex — which he does enthusiastically and at considerable length, thanks to his superhuman stamina and a staggering variety of nubile young women eager to assist him in his research. But the place where Lawrence left his most obvious mark was a series of books about a young scientist/inventor/adventurer named Tom Swift, Jr.

The original Tom Swift was created by publishing pioneer Edward Stratemeyer, founder in the very early twentieth century of the so-called Stratemeyer Syndicate and its accompanying model of children’s book publication — a model that still persists to this day, and one whose echoes we can see in other media from superhero comics to Scooby Doo cartoons. His influence on publishing for adults and young adults was also profound; all those shelves full of Star Trek and Star Wars novels as well as Harlequin romances are, for better or for worse, thoroughly in the tradition of Edward Stratemeyer. His principal innovation was to deemphasize — indeed, to effectively do away with — the importance of the author in favor of the franchise. He published no standalone books, only series based around the recurring adventures of one or more juvenile heroes. All books in a series were allegedly written by the same author, whose name was carefully chosen by Stratemeyer to suit the tone of the series. In actuality, the books were written by teams of publishing B-listers like Jim Lawrence, who must at first usually work from plot outlines provided by Stratemeyer himself. Later, once they had proven themselves a bit, they were often trusted to create their own original stories, as long as they kept well within a detailed set of rules for what the books should and should not include. The best remembered series from Stratemeyer’s heyday today are The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, but many others sold in huge quantities during the first half of the twentieth century.

Among them were the original Tom Swift stories, which reached 40 books and sold over 30 million copies. Swift was the aspirational product of his era, a time when people like Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and Henry Ford were amongst the most admired in the country. Thus Swift was a teenage genius inventor who solved crimes and stymied his jealous rivals repeatedly using his various gadgets and vehicles. For all their pulpiness, the books included a surprising amount of real science and engineering. Amongst the technologies predicted in their pages were television, fax machines, and handheld movie cameras. Just as many flip-open mobile phones bear a suspicious resemblance to the old communicators from Star Trek, Tom Swift also wound up inspiring some technologies instead of just predicting them. Most famously, tasers were inspired by a Tom Swift story; the name is actually a loose acronym for “Tom Swift’s Electric Rifle.”

The series petered to a close in 1941, by which time Swift had grown up and gotten married. The resulting drop-off in popularity prompted a couple of new rules for the Stratemeyer Syndicate’s other series: heroes should not age and should be kept free of romantic entanglements. The Tom Swift, Jr. stories, which began in 1954, were an attempt to right that mistake and turn back the clock by moving the focus to Tom Swift’s son, the spitting image of his father as a boy. The new series ran for 33 books between 1954 and 1971. The inventions got a bit more outlandish, reflecting the era’s obsession with rocketry and space exploration; the second series’s record of prediction is nowhere near as good as that of the first. The new series also never quite matched the first’s popularity or cultural ubiquity during its heyday. Still, it had its famous fans; Steve Wozniak in particular has mentioned the Tom Swift, Jr. books as inspiring him to become an inventor and engineer. Tom Swift Jr. was allegedly written by one Victor Appleton II, presumed son of the Victor Appleton who wrote the first series. However, most of them were actually written by Jim Lawrence.

Lawrence had long since moved on to other series when one day during his morning coffee he read the first significant article about Infocom to appear in the mainstream media: Edward Rothstein’s piece on Deadline and other “participatory novels” which appeared in the New York Times Book Review of May 8, 1983. Although he had never written for the series, he had followed the birth of the Choose Your Own Adventure line of children’s fiction with more than professional curiosity. But now what Infocom was apparently doing just sounded so much better. Lawrence, whose previous career proved if nothing else that he’d try just about anything once, was intrigued by the possibilities despite knowing nothing of computers or computer games. He called Infocom’s offices and arranged to drive up to Cambridge for a visit from his home in New Jersey.

The 65-year-old Lawrence looked in Stu Galley’s words “like Santa Claus,” and had the same enthusiastic twinkle in his eye when he talked about storytelling. This wise old veteran was certainly a different sort of presence in an office filled with ambitious go-getters in their twenties and early thirties, many of whom had grown up reading the various series to which he had contributed. Infocom, who counted it as a corporate goal to get “real” writers involved with their stories (thus the presence of Mike Berlyn, already working on his second game at the time), were thrilled to sign him to a contract.

Infocom was also, of course, eager to branch out into new genres, and here Lawrence’s particular expertise again seemed perfect. They concocted the idea of a new line of “junior” adventures aimed at a new generation of the same children’s readership that had once devoured the Tom Swift books — and who were currently being introduced to the idea of ludic narrative through the Choose Your Own Adventure books and the many other titles being churned out by the booming gamebook industry. If kids thought Choose Your Own Adventure was cool, wait until they saw an Infocom game! The new line could presumably also serve as a gentle introduction to Infocom for adults, an alternative to being thrown in at the deep end via the likes of Zork. Infocom made their first attempt ever to license an existing property, approaching the Stratemeyer Syndicate about licensing Tom Swift or his son for a series of interactive books for a new generation. The Syndicate was happy to do so — for far more money than Infocom was willing or able to pay.

Thus the decision was made to make the game that would become known as Seastalker a Tom Swift adventure in everything but name. In place of Tom, it asks you the player for your first and last name at the beginning. The full name which then appears on the screen becomes (for example) Seastalker: Jimmy Maher and the Ultramarine Bioceptor, a deliberate echo of the old Tom Swift books, which were invariably named Tom Swift and His (Flying Lab, Jetmarine, Rocket Ship, etc.) — only with you inserted, Choose Your Own Adventure-style, as the hero. The game closely echoes Tom Swift in many other ways beyond the bare fact of your being a genius boy inventor. Tom Swift’s hometown of Shopton, for example, becomes Frobton (one of very few overt references to Zorkian lore), and sidekick Bud is replaced with a doppelganger named Tip.

For all of his flair for storytelling, there was no way that the thoroughly un-technical Lawrence was going to be able to learn to program in ZIL. Infocom thus decided to assign him Stu Galley as a partner. Lawrence would craft the story and write most of the text, while Galley would program it and find ways to make it work as an interactive experience. It seemed a perfect assignment for Galley, one of the best pure programmers in a company full of brilliant technical minds but one who tended to have a bit of trouble coming up with original story ideas. (His first game The Witness, you may remember, had been created from an outline provided him by Marc Blank and Dave Lebling.) This use of development pairs was somewhat uncharted territory for Infocom as Seastalker was begun, but a model they would find themselves using for no fewer than three of the five games they would release in 1984.

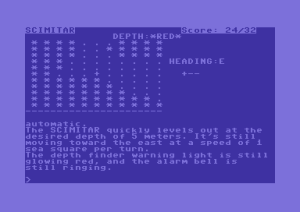

Work on Seastalker commenced with a lengthy meeting between Lawrence and Galley at Infocom’s offices, during which they hashed out the basic plot: a genetically engineered sea monster is attacking your friends at the Aquadome undersea research station. Only you and sidekick Tip can save them, using the Scimitar, the experimental two-man research submarine you’ve just designed and built. Lawrence then went back home to New Jersey, and development progressed largely through paper mail and telephone calls, with just a few more in-person meetings to mark milestones. Working this way inevitably slowed the process — at more than nine months, Seastalker would have the longest active gestation of any Infocom game to date — but Galley generally found the project to be, like his gently unflappable collaborator, a delight.

There was a time when we got to the last act of the story, where you, the brilliant young inventor, know what the threat is, know what you have to work with (your own inventions and whatever else is available), know the other characters. How do we devise a game strategy that’s interesting but not too difficult to get you to the end? Jim and I worked on this a whole day in Cambridge. I told him, “I feel like we have a big job in front of us because we’ve set up all this elaborate storyline without really knowing how it’s going to end.” Jim said, “Don’t worry, Stu, I’ve gotten heroes out of much tougher situations than this.”

Unlike many established traditional authors who tried to make the leap to interactivity, Lawrence didn’t struggle hugely with his loss of control over every aspect of plotting and timing. Galley theorizes that he may have been aided by his experience writing for comic strips and comic books, for which he had to start putting stories down on paper long before he could foresee what their endings might be or even which writers for hire might end up writing them.

As one might expect given its pedigree, Seastalker absolutely nails the tone of its inspiration. Its gee-whiz world is full of adventure and excitement, one where no problem cannot be solved with a bit of science and a dollop of all-American bravery and ingenuity. It’s never afraid of going over the top; the package includes a letter from the President congratulating you on your latest invention. As fiction, Seastalker makes for a nice, nostalgic place to return to for some of us dealing with the vagaries of adult life. Yet as a system it’s also amongst the most complex things Infocom had yet attempted. Playing Seastalker really does feel, for the first time in an Infocom game and arguably in an adventure game, like taking the leading role in an adventure novel. Events tumble down around you one after another as the plot comes thick and fast, leaving you constantly scrambling to keep up, to save these people who make it clear they’re depending on you. Seastalker is all about its plot that just keeps pushing you along like a bulldozer. There’s little here that feels like a traditional adventure-game puzzle, little time for such cerebral exercises. Even that staple of adventure gaming, mapping, goes out the window thanks to the blueprints of the Scimitar and the maps of both undersea complexes you’ll be visiting included in the package, a first for Infocom. While Deadline and The Witness have a dynamism of their own, their characters go about their business oddly oblivious to you; your job is essentially to observe their behavior, to come to an understanding of their patterns, and then to force yourself into the plot to redirect it at crucial junctures. No forcing is required in Seastalker; you truly are the hero, the cog around which everything and everybody revolves.

One of the most impressive parts of Seastalker is its implementation of the Scimitar. You have to guide it around Frobton Bay yourself, using your sonar display and a depth map included in the package. Later, the climax of the story is an underwater battle involving the Scimitar, the sea monster, and the jealous rival behind all the chaos that is a genuine tactical struggle rather than an exercise in set-piece puzzle solving. For these sequences Infocom devised the first significant extension to the Z-Machine since its inception more than four years before: the ability to split the screen on certain computers, which Seastalker uses to display a non-scrolling upper window that shows your sonar screen as a simple textual rendering. (The member of the Micro Group responsible for moving this enhancement into the interpreters was the newly hired Brian Moriarty, a name we’ll soon be hearing a lot more of.)

Seastalker‘s feelies are, as you might have gathered given the wealth of maps and blueprints I’ve already described, unusually many and varied even for Infocom. There’s a clever set of “InfoCards” with hints printed in a special ink that can only be seen with the aid of an included InfoCard reader — just the sort of little gadget young Tom Swifts are likely to love. But Seastalker‘s packaging is most interesting today in that it serves as a sort of test run for much of what would follow just a month or two later, when Infocom converted their entire existing line of games into a new standardized packaging format, the classic and beloved “grey box.” We have a sample transcript showing how to interact with the game, an invaluable bit of teaching by example that would be included in every grey box to come. And the front of the box calls the game “Junior Interactive Fiction from Infocom.”

Infocom, despite a generally finely honed promotional instinct, had struggled for years to find a good label for what their games really were, wallowing around in unsatisfying pseudo-compounds like “InterLogic” and plebeian descriptives like “prose games.” Some of the Imps had at last begun to casually refer to their games as “interactive fiction” in interviews during the latter half of 1983, notably in a feature article in the September/October 1983 Softline which dwelt at length on Floyd’s death scene from Planetfall. Seastalker, however, marks its first deployment as part of Infocom’s official rhetoric — appropriately enough, given that Seastalker is more worthy of the label than anything that came before. Infocom wasn’t the first to use the term “interactive fiction” in a computerized context; that honor belongs to Robert Lafore, who created a set of simple branching stories to which he gave that label back in 1979. Yet it was perfect for Infocom’s games, the last piece of the rhetorical puzzle they had been assembling with the able assistance of their mates at G/R Copy for a few years now. With the arrival of the grey boxes, all of Infocom’s games would officially be interactive fiction, the name the whole field of literary games in the Infocom tradition continues to go by to this day.

Released in June of 1984, Seastalker initially sold very well: more than 30,000 units in its first six months. But sales tailed off rather quickly after that; its lifetime figure is in the vicinity of 40,000. It may very well have been a victim of Infocom marketing’s conflation of a game for kids with an introductory game for adults. Certainly Seastalker is very short. Any adult at all experienced with adventure games can easily finish it in an evening, any adult totally inexperienced at least within two. One suspects that the arrival in 1985 of Wishbringer, a much better introductory game for adults, ate into Seastalker‘s sales in a big way.

But then Seastalker wasn’t really designed for adults. Children, who read more slowly and have the patience to relive something over and over (and over…) will likely get considerably more out of it, especially since there are a fair number of alternate paths to follow and even the possibility to finish without the full score; if you screw the pooch, one of your heretofore helpless friends will often stop hand-wringing long enough to jump in at the last minute and save the day for you. Still, it’s debatable how many parents would have been willing to spend $30 or $40 on the game when they could pick up a Choose Your Own Adventure book for $2.

All of which leaves Seastalker feeling like a bit of a missed opportunity in spite of its perfectly reasonable commercial performance. Stu Galley recalls that Infocom demonstrated Seastalker for a group of schoolteachers at the 1984 Summer CES show to the rapturous response that this sort of thing was “just what they needed” to get their kids reading more. One wishes that Infocom could have found some way to reduce the price and/or work aggressively with schools to get the game into more children’s hands. As it was, they dropped the idea of “Interactive Fiction Junior” and of trying to compete with the Choose Your Own Adventure juggernaut within a year, relabeling Seastalker rather incongruously as an introductory-level game for adults like the aforementioned Wishbringer. Even Lawrence and Galley’s second collaboration, Moonmist, was largely marketed as just another adult mystery game despite being at heart a Nancy Drew story in the same way that Seastalker was a Tom Swift.

If you have a child in that sweet spot of about eight to ten years in your life, you can begin to remedy that missed opportunity by giving her Seastalker and seeing what she makes of it. Like so much of Infocom’s work, it’s aged very little. For the rest of us, it’s a great piece of innocently cheesy fun that’s also quite technically and even formally impressive in its way. Infocom never made another game quite like it, which is alone more than reason enough to play it.

(As always, thanks to Jason Scott for sharing his materials from the Get Lamp project.)

ZUrlocker

September 3, 2013 at 4:35 pm

Great story! I had no idea Jim Lawrence had written so much serial fiction.

matt w

September 3, 2013 at 6:23 pm

Wow, this sounds great! And even for us grownups whose children aren’t old enough yet, lots of those flaws aren’t flaws anymore; now that it’s not $20-30 a game anymore, being able to finish in a day or two seems like a good thing.

Gilles Duchesne

September 3, 2013 at 9:05 pm

“His ouevre”

That’s spelled “oeuvre”.

Jimmy Maher

September 4, 2013 at 6:07 am

Thanks!

Keith Palmer

September 5, 2013 at 1:25 am

I was just the age you suggest for “the sweet spot” when Seastalker was first released, and I was playing adventure games then (if hardly ever managing to win them)… except that I didn’t get to play the game until The Lost Treasures of Infocom 2 came out, at which point it might not have made that much of an impact on me beyond the sonar display, perhaps. Still, the “introductory” adventures Moonmist, Seastalker, and Wishbringer are the only Infocom games I have an impression of finishing without turning to hints. Your description does make me think I could well enjoy it more now; for some reason, it’s pleasant to hear one of its authors really had written the old juvenile series fiction I’d only thought it was “modelled on” (as much as that sort of thought seems to tempt people into too-quick dismissals…)

Scott M. Bruner

September 19, 2013 at 2:45 am

I remember vividly playing Seastalker when we moved from California to Nebraska when I was…11 or 12? The house was empty as we waited for the movers to catch up and we didn’t even have a desk for the Apple //c, but it sat on my lap as I worked my way through it.

In my memory, it took about 5 days to complete, and I was pretty proud of myself – the other Infocom games, notable Suspect, always seemed a little difficult to fully grasp.

Peter Piers

April 9, 2016 at 9:25 am

I’ve just played it… and it may be the one Infocom game I haven’t played to completion.

At one point, I couldn’t really ask NPCs about important things. Asking Tip about his idea or asking crew members about the Snark once I’m ready to go at it brings up the “Use the clue sheet if you need help” – and nothing else, no reply from the NPCs. I don’t know whether this is an issue or just copy-protection. Anyway, I’m playing it without access to the clue sheets, so…

And then there’s the confusion when you get to the Aquadome, after you’ve sorted the oxygen thing. Things keep happening, you’re being asked questions and you quickly realise that if you answer YES you move the story along and if you answer NO you don’t, so I was saying “Yes, Tip, Bly told me about the troublemakers” even though she’d done no such thing… I’m swept along, then I’m asked whether I’m ready to go on, I answer YES in a daze mostly because I’m afraid I’ll break something if I say no, then I worry about all the things I may have done to lock me out of victory later.

I suppose the clue sheets are an integral part of the experience, and meant to be used, given the target audience. Well, I had a hard time getting motivated to play this game (I’d tried it years before on a different mobile interpreter, which wasn’t as good as the one I’m using now), and after I’d identified and trapped the traitor I’d pretty much had enough…

Jimmy, what was your experience with all the prompting for the clue sheets? Did they, in your playthrough, also totally replace NPCs’ critical dialog responses?

Jimmy Maher

April 10, 2016 at 7:13 am

As I recall, I regarded the clue sheets as just that, clue sheets, and didn’t use them either. I don’t recall any missing dialog. Maybe your game somehow went down the wrong track…

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 8:12 am

Maybe. Testing will be required. Thanks for the input.

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 8:26 am

Hmmm, the same thing happens in my Windows terp.

“”First, do you think someone tampered with it?” >y

“Does Marv suspect you’ve discovered signs of tampering?” >n

“Then I have an idea how to trap Marv and find out if he’s the traitor!”

>ask tip about idea

(If you want a clue, find Infocard #1 in your SEASTALKER package. Read hidden clue #3 and put “Marv Siegel” in the blank space.)”

…and later the same thing happened when, apparently, I should have asked the crew about the snark’s location

What’s more, the walkthrogh I was now running does say:

“Tip will

appear around this point to ask a series of questions.

Answer his questions however you like and he will say that he may have an idea

how to trap Marv if he is the traitor. “Ask about idea”, and Tip will say to

put the black box where Zoe found it.”

Weird! The version I’m playing is “Revision number 16 / Serial number 850603”, that’s the latest one, innit?

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 8:30 am

I just re-downloaded this version from an abandonware site, played back the playback file I’d recorded, and got the same result. Sheesh.

Jimmy Maher

April 10, 2016 at 8:39 am

I think the parser is simply not understanding you, rather than trying to direct you to a specific “clue” containing vital information. I’d try “ask about” or “question tip” — the latter is the syntax given in the manual — rather than “ask tip about.” If I’m right, it’s obviously not ideal that the parser doesn’t understand “ask tip about.” In Seastalker’s defense, that construction wasn’t very common in 1984; it’s since of course become second nature to most IFers. So some of your problem may be anachronistic.

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 9:02 am

Interesting thought, although I wouldn’t have expected it to be that because the walkthrough I was now following did say “ask about”.

Anyway, it didn’t work, I’m afraid.

“>question tip

“Ask me about something in particular, First.”

>question tip about idea

(If you want a clue, find Infocard #1 in your SEASTALKER package. Read hidden clue #3 and put “Marv Siegel” in the blank space.)

>ask about idea

(If you want a clue, find Infocard #1 in your SEASTALKER package. Read hidden clue #3 and put “Marv Siegel” in the blank space.)”

I didn’t expect it to be this because, up until now, it had been handling ASK ABOUT as gracefully as though it HAD been the intended syntax all along…

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 9:20 am

Slight correction – no, the walkthrough did not tell me to “ask tip about idea”. Sometimes words just run together and get overlooked, sorry. :) But the output I provided is clear enough anyway, and does include “ask about idea”.

Jimmy Maher

April 10, 2016 at 10:08 am

Okay, I see the same thing in my old transcript. I think the “idea” Tip has must be intended as extra information — i.e., a hint — rather than something essential. I’m sure I never used the InfoCards, and nevertheless won the game quite easily. The game could certainly have handled this more gracefully, however.

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 10:38 am

Oh, I completely ignored this and accidently found the traitor another way very easily. That’s also why I thought it was just a clue. Maybe the walkthrough conflated things a bit, too.

Ah well, at least I know it wasn’t just me. You know, for some reason this game really, really got on my nerves. I fought it more than I fought any other Infocom game. Strange, huh?

Jimmy Maher

April 10, 2016 at 10:43 am

Probably just a mismatch of expectations. It’s very much written for children, and that can easily come off as grating and condescending to an adult. It’s not a particularly beloved Infocom game, although I think it’s a very interesting and significant one for the reasons described in the article.

Peter Piers

April 10, 2016 at 10:42 am

I think it was the hand-handling. I hate it when games expect you to follow their lead sometimes and go off on your own othertimes. Cutthroats did that, as you know, in the bit where you can easily fail to identify the traitor. In the Aquadome I was being led so obviously, and so clearly expected to answer in a certain way, that I was in a daze most of the time.

Vince

January 28, 2024 at 6:00 pm

I had the same experience as Peter (of course, playing for the first time as an adult).

I thought the game was jarring in the way it often interrupts the player and too insisting on using the clues when it could have just given the information as expected. Of course, probably a kid would welcome the assistance and would consider using the sheets fun, rather than looking at hints.

The sub parts were excellent though, definitely more entertaining than the more complex ones in Codename: Iceman years later.

Joe W

January 2, 2017 at 7:44 am

I just finished Seastalker tonight for the first time. Missed it as a kid.

*Spoilers follow*

However, I think I encountered a strange bug. I know that if you take too many turns getting to the Aquadome, the monster will destroy it. By “waiting” I noticed that this happens sometime after turn 400 or so.

However, on my first attempt, I made it to the Aquadome around turn 315. I went inside, and at turn 323, the monster attacked, and destroyed the dome. Nothing I could do prevented that. When I restarted, I waited in the ocean deliberately until after turn 323, and went in the dome at turn 384, and there was no attack. I restarted again and made it to the dome on turn 100. Again, no attack. I could not figure out what was causing the attack to happen inescapably at turn 323 in that one save file, and not in any other attempt. Someone at the IF fansite indicated that it was related to the black box that supposedly caused the monster to attack the dome, but as near as I could tell, that part of the story is not variable and always happens the same way. Weird.

Lisa H.

January 2, 2017 at 9:32 pm

I think it’s probably not a bug, but that the turn the attack will happen on is picked randomly within a certain range of turn numbers at the start of the game. Compare the earthquake in Zork III, for instance. (I haven’t decompiled code to know for sure; I’m only guessing because of the observed behavior.) I haven’t played Seastalker in quite a while so I’m not sure what you mean about “related to the black box”, but if it’s a thing that can direct you to different sets of coordinates on different playthroughs (similar to how there are different wrecks you can visit in Cutthroats) then perhaps the range of turns the attack can occur on would be different in the different storylines.

Tom Swift

March 20, 2024 at 4:48 am

Precisely the same thing is happening to me. Monster appears at 323, then a couple turns later you’re dead and can do nothing about it. Very annoying.

DZ-Jay

February 21, 2017 at 11:49 am

Great write up! I don’t recall playing this game as a kid, but I will run out and play it now. It sounds fascinating. :)

One thing… I cringed when I read “if you screw the pooch.” Eek! Please try not to use such boorish slang in you otherwise perfectly eloquent prose.

-dZ.

Joe Pranevich

December 30, 2017 at 2:32 am

I know you looked at this years ago, but I am trying to pull together a complete list of books by Jim Lawrence. Thus far, I have identified 62 books, three radio series that he did scripts for, plus five newspaper comics. You can see what I have found here: https://kniggit.net/2017/11/07/jim-lawrences-bibliography/

I do not know if you stumbled on any other books in your research, or if any of your readers may know more. For such an (at times) amazing writer, it seems a shame that we do not have a complete list of his works. (I do not know his personal life and I hope I do not discover that he’s a serial racist or something while researching him. That would be disappointing.)

I have only read one Tom Swift but I recognized the style immediately when playing Seastalker. It seems so close that I’m half-surprised that Infocom didn’t get sued over the similarities.

Jimmy Maher

December 30, 2017 at 8:58 am

Have you been in contact with his son? I’m not even sure of his name off the top of my head, but he’s apparently very interested in preserving his father’s legacy. He speaks at conferences about his work, etc. Jason Scott has mentioned that he considered interviewing him for the Get Lamp documentary, but didn’t have time in the end.

Joe Pranevich

December 30, 2017 at 11:19 pm

I have found interviews with his son, but no contact information. I will reach out to Jason to see if he has it.

Joe Pranevich

March 19, 2018 at 5:39 am

Just to close on this thread, Jason did not have that contact information and the few other threads that I pulled on this have gone nowhere. I hope I’ll be able to find him before I research Moonmist, but I have a few months at least for that.

Mike Taylor

March 8, 2018 at 4:29 pm

Even that staple of adventure gaming, mapping, goes out the window thanks to the blueprints of the Scimitar and the maps of both undersea complexes you’ll be visiting included in the package, a first for Infocom.

What about Suspended?

Jimmy Maher

March 9, 2018 at 8:37 am

It’s a debatable point, but I tend to see the Suspended “map” as a qualitatively different sort of thing. Oddly given that it appeared so early in the chronology, Suspended was one of Infocom’s most formally experimental games, really more of a strategy game implemented in text than a text adventure. The map included in the original packaging was actually a game board with tokens for keeping track of the locations of the robots, a way of overcoming the limitation of the text-only presentation.

Wolfeye M.

September 2, 2019 at 12:26 am

Wow, another bit from my childhood pops up in your blog. My dad had a bunch of Tom Swift Jr. books he got while he was growing up, which he then gave to me. I still have them, in a box somewhere. They’re some of the first books I ever read, and were some of my favorites. I didn’t know they were ghost written. I owe Jim Lawrence for many hours of enjoyable reading. I’ll have to check out the game he wrote.

Allan Holland

March 11, 2020 at 2:28 am

I’m a huge fan of Steve’s Infocom work. And the 101 series. To be called “the most creative person he’s ever met” by Mike Dornbrook is the highest praise, the kind of character trait of which I can only dream about possessing. Mike, as founder of the Z.U.G., has probably met his fair share of creative people.

Jonathan O

December 29, 2020 at 10:30 am

Late typo report:

“as well as Harelquin romances” -> “as well as Harlequin romances”

Jimmy Maher

December 29, 2020 at 4:22 pm

Thanks!

Ben

April 17, 2021 at 9:24 pm

Chose Your Own Adventure -> Choose Your Own Adventure

closely echos -> closely echoes

finds ways -> find ways

(You may have missed https://www.filfre.net/2013/08/from-automated-simulations-to-epyx/#comment-580679 )

Jimmy Maher

April 18, 2021 at 10:35 am

Thanks! (Also for the nudge on your previous corrections; got them too now.)

Steve Pitts

June 2, 2021 at 4:14 pm

“Its is a gee-whiz world” -> “It is a…” or “It’s a…”

Jimmy Maher

June 4, 2021 at 4:17 pm

Thanks, but as intended actually. ;)

Steve Pitts

June 5, 2021 at 6:18 pm

OK. I’ve re-read it until the sentence makes sense but I certainly didn’t read it that way to start with. Sorry to bother you :)

Lisa H.

June 7, 2021 at 6:38 pm

For what it’s worth, I found it kind of confusing too – sort of a “garden path” sentence where the end isn’t what you expected from the beginning and you have to go back and re-read it. I might have phrased it as “Its world is a gee-whiz one full of adventure…”

Jimmy Maher

June 8, 2021 at 2:28 pm

Fair enough. Thanks!

Peter Olausson

June 30, 2021 at 10:13 am

Comment (correction?) long overdue: Regarding the title of the book, “Thomas A. Swift and his Electric Rifle”, that eventually turned into TASER. Are you sure about this? I find the “Thomas A.”-form frequently mentioned, but no book with any other title than just “Tom Swift and …” – I think Jack Cover, who invented and named the taser, took the abbreviation TSER and added an “a” on his own.

Jimmy Maher

July 1, 2021 at 11:07 am

I’m not sure I completely understand your objection. But, if it isn’t something more granular you’re getting at, there are a couple of UK newspaper articles which describe this etymology at https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/jack-cover-inventor-taser-stun-gun-1635270.html and https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/30/history-of-word-taser-comes-from-century-old-racist-science-fiction-novel.

Peter Olausson

July 1, 2021 at 6:52 pm

I agree completely with the etymology. What I refer to is “Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle.” The title of the book is “Tom Swift and His Electric Rifle.” The “Thomas A.”-phrase seems to be made up.

Very, very tiny nitpicking in an excellent article. I went so far as to read some of the book in question. Great writing it ain’t! But is certainly has a certain something.

Jimmy Maher

July 1, 2021 at 8:42 pm

Ah, okay. I suppose if he *said* it was an acronym for “Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle,” then it was, whether the phrase in question is actually drawn from the book or not. But I made an edit to eliminate any confusion. Thanks!

whomever

July 2, 2021 at 1:18 pm

I mean…TASAR is a lot more pronounceable then TSAR. May even be a backronym!

Lava Ghost

July 30, 2021 at 9:16 am

Hi Jimmy,

Regarding “For the first time we see in Seastalker a sample transcript showing how to interact with the game, an invaluable bit of teaching by example that would be included in every grey box to come.”

I think this is incorrect. I was looking at the folio release of Sorcerer on MoCAGH the other day and there does appear to be a sample transcript in its verion of the “Popular Enchanting” magazine. For what it’s worth I looked and I can’t find any sample transcripts before that.

Jimmy Maher

August 3, 2021 at 1:27 pm

Good catch. Thanks!

Doug Hudson

August 8, 2021 at 3:01 am

I had Seastalker for the Apple when I was about 10… I remember getting fairly far along in it without clues although I can’t remember for sure. I did buy the clue book at one point. I think I at least did the “fix the oxygen” puzzle on my own… I know there was a point where I wasn’t sure how to continue, I’m not sure if it was trapping the traitor or finding the poisom needle in the Scimitar.

I think the red/blue clue cards were lost but I still have the main game “folder” and manual…

…and, of course, my Discovery Squad sticker, which is attached to an old plastic box used for holding 5.25 floppies.

Jeff Nyman

October 4, 2021 at 6:29 pm

“…and who were currently being introduced to the idea of ludic narrative through the Choose Your Own Adventure books and the many other titles being churned out by the booming gamebook industry.”

This is something that I have always wondered if Infocom had missed a particular boat on. Or, rather, an avenue they chose not to explore in any depth that might have done more to get Infocom games in schools, similar to what “The Oregon Trail” did.

Understood that the Syndicate may have been a tough customer in terms of what they wanted for compensation, but it’s not like gamebooks were having any trouble coming up with themes and ideas.

This article echoes a bit later:

“One wishes that Infocom could have found some way to reduce the price and/or work aggressively with schools to get the game into more children’s hands.”

Even if not just this game, more the idea of leveraging the school system to introduce their concepts to a much wider audience than it possibly would have been exposed to otherwise. Who knows if it would have worked but it’s quite possible it would have opened up more avenues. Or maybe they did think about this and rejected it for a variety of reasons, which would also be interesting to learn.

Jeff Nyman

October 4, 2021 at 6:30 pm

“Lawrence didn’t struggle hugely with his loss of control over every aspect of plotting and timing.”

Yep, one of the more fascinating aspects of the story. The history of interactive fiction seems to suggest that actually having established writers at the helm was a very mixed bag, at best. This is another area where I think Infocom fell prey to very limited thinking. “We’re writing interactive fiction! So it’s like a book but just … interactive.” Yet, as was shown historically, that really never actually worked. As this post so adequately states:

“Playing Seastalker really does feel, for the first time in an Infocom game and arguably in an adventure game, like taking the leading role in an adventure novel.”

Yep! Unfortunately, Infocom entirely failed to realize this and try to expand on it.

Even more adequately said:

“While Deadline and The Witness have a dynamism of their own, their characters go about their business oddly oblivious to you; your job is essentially to observe their behavior, to come to an understanding of their patterns, and then to force yourself into the plot to redirect it at crucial junctures. No forcing is required in Seastalker; you truly are the hero, the cog around which everything and everybody revolves.”

YES! So much this! All of the text adventures that truly tried for any sort of dynamism fell prey to exactly this. You felt like you were living someone else’s story and you had these limited interaction points at which you could guide the story.

“Like so much of Infocom’s work, it’s aged very little.”

I personally think most of Infocom’s work has aged terribly. And I speak as someone who has used interactive fiction in the context of classroom studies with children as well as in groups of writers, often with certain Infocom games as examples. But I do agree that Seastalker is actually one of the very, very few games that actually does hold up, when you allow for its context and its intended audience.