Fair warning: spoilers for Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers are to be found herein!

In 1989, a twenty-something professional computer programmer and frustrated horror novelist named Jane Jensen had a close encounter with King’s Quest IV that changed her life. She was so inspired by the experience of playing her first adventure game that she decided to apply for a job with Sierra Online, the company that had made it. In fact, she badgered them relentlessly until they finally hired her as a jack-of-all-trades writer in 1990.

Two and a half years later, after working her way up from writing manuals and incidental in-game dialog to co-designing the first EcoQuest game with Gano Haine and the sixth King’s Quest game with Roberta Williams, she had proved herself sufficiently in the eyes of her managers to be given a glorious opportunity: the chance to make her very own game on her own terms. It really was a once-in-a-lifetime proposition; she was to be given carte blanche by the biggest adventure developer in the industry at the height of the genre’s popularity to make exactly the game she wanted to make. Small wonder that she would so often look back upon it wistfully in later years, after the glory days of adventure games had become a distant memory.

For her big chance, Jensen proposed making a Gothic horror game unlike anything Sierra had attempted before, with a brooding and psychologically complex hero, a detailed real-world setting, and a complicated plot dripping with the lore of the occult. Interestingly, Jensen remembers her superiors being less than thrilled with the new direction. She says that Ken Williams in particular was highly skeptical of the project’s commercial viability: “Okay, I’ll let you do it, but I wish you’d come up with something happier!”

But even if Jensen’s recollections are correct, we can safely say that Sierra’s opinion changed over the year it took to make Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers. By the time it shipped on November 24, 1993, it fit in very well with a new direction being trumpeted by Ken Williams in his editorials for the company’s newsletter: a concerted focus on more “adult,” sophisticated fictions, as exemplified not only by Sins of the Fathers but by a “gritty” new Police Quest game and another, more lurid horror game which Roberta Williams had in the works. Although the older, more lighthearted and ramshackle [this, that, and the other] Quest series which had made Sierra’s name in adventure games would continue to appear for a while longer, Williams clearly saw these newer concepts as the key to a mass market he was desperately trying to unlock. Games like these were, theoretically anyway, able to appeal to demographics outside the industry’s traditional customers — to appeal to the sort of people who had hitherto preferred an evening in front of a television to one spent in front of a monitor.

Thus Sierra put a lot of resources into Sins of the Fathers‘s presentation and promotion. For example, the box became one of the last standout packages in an industry moving inexorably toward standardization on that front; in lieu of anything so dull as a rectangle, it took the shape of two mismatched but somehow conjoined triangles. Sierra even went so far as to hire Tim Curry of Rocky Horror Picture Show fame, Mark Hamill of Star Wars, and Michael Dorn of Star Trek: The Next Generation for the CD-ROM version’s voice-acting cast.

Jane Jensen with the first Gabriel Knight project’s producer and soundtrack composer Robert Holmes, who would later become her husband, and the actor Tim Curry, who provided the voice of Gabriel using a thick faux-New Orleans accent which some players judge hammy, others charming.

In the long run, the much-discussed union of Silicon Valley and Hollywood that led studios like Sierra to cast such high-profile names at considerable expense would never come to pass. In the meantime, though, the game arrived at a more modestly propitious cultural moment. Anne Rice’s Gothic vampire novels, whose tonal similarities to Sins of the Fathers were hard to miss even before Jensen began to cite them as an inspiration in interviews, were all over the bestseller lists, and Tom Cruise was soon to star in a major motion picture drawn from the first of them. Even in the broader world of games around Sierra, the influence of Rice and Gothic horror more generally was starting to make itself felt. On the tabletop, White Wolf’s Vampire: The Masquerade was exploding in popularity just as Dungeons & Dragons was falling on comparatively hard times; the early 1990s would go down in tabletop history as the only time when a rival system seriously challenged Dungeons & Dragons‘s absolute supremacy. And then there was the world of music, where dark and slinky albums from bands like Nine Inch Nails and Massive Attack were selling in the millions.

Suffice to say, then, that “goth” culture in general was having a moment, and Sins of the Fathers was perfectly poised to capitalize on it. The times were certainly a far cry from just half a decade before, when Amy Briggs had proposed an Anne Rice-like horror game to her bosses at Infocom, only to be greeted with complete incomprehension.

Catching the zeitgeist paid off: Sins of the Fathers proved, if not quite the bridge to the Hollywood mainstream Ken Williams might have been longing for, one of Sierra’s most popular adventure games of its time. An unusual number of its fans were female, a demographic oddity it had in common with all of the other Gothic pop culture I’ve just mentioned. These female fans in particular seemed to get something from the game’s brooding bad-boy hero that they perhaps hadn’t realized they’d been missing. While games that used sex as a selling point were hardly unheard of in 1993, Sins of the Fathers stood out in a sea of Leisure Suit Larry and Spellcasting games for its orientation toward the female rather than the male gaze. In this respect as well, its arrival was perfectly timed, coming just as relatively more women and girls were beginning to use computers, thanks to the hype over multimedia computing that was fueling a boom in their sales.

But there was more to Sins of the Father‘s success than its arrival at an opportune moment. On the contrary: the game’s popularity has proved remarkably enduring over the decades since its release. It spawned two sequels later in the 1990s that are almost as adored as the first game, and still places regularly at or near the top of lists of “best adventure games of all time.” Then, too, it’s received an unusual amount of academic attention for a point-and-click graphic adventure in the traditional style (a genre which, lacking both the literary bona fides of textual interactive fiction and the innate ludological interest of more process-intensive genres, normally tends to get short shrift in such circles). You don’t have to search long in the academic literature to find painfully earnest grad-student essays contrasting the “numinous woman” Roberta Williams with the “millennium woman” Jane Jensen, or “exploring Gabriel as a particular instance of the Hero archetype.”

So, as a hit in its day and a hit still today with both the fans and the academics, Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers must be a pretty amazing game, right? Well… sure, in the eyes of some. For my own part, I see a lot of incongruities, not only in the game itself but in the ways it’s been received over the years. It strikes me as having been given the benefit of an awful lot of doubts, perhaps simply because there have been so very few games like it. Sins of the Fathers unquestionably represents a noble effort to stretch its medium. But is it truly a great game? And does its story really, as Sierra’s breathless press release put it back in the day, “rival the best film scripts?” Those are more complicated questions.

But before I begin to address them, we should have a look at what the game is all about, for those of you who haven’t yet had the pleasure of Gabriel Knights’s acquaintance.

Our titular hero, then, is a love-em-and-leave-em bachelor who looks a bit like James Dean and comes complete with a motorcycle, a leather jacket, and the requisite sensitive side concealed underneath his rough exterior. He lives in the backroom of the bookshop he owns in New Orleans, from which he churns out pulpy horror novels to supplement his paltry income. Grace Nakimura, a pert university student on her summer holidays, works at the bookshop as well, and also serves as Gabriel’s research assistant and verbal sparring partner, a role which comes complete with oodles of sexual tension.

Gabriel’s bedroom. What woman wouldn’t be excited to be brought back here?

Over the course of the game, Gabriel stumbles unto a centuries-old voodoo cult which has a special motivation to make him their latest human sacrifice. While he’s at it, he also falls into bed with the comely Malia, the somewhat reluctant leader of the cult. He learns amidst it all that not just voodoo spirits but many other things that go bump in the night — werewolves, vampires, etc. — are in fact real. And he learns that he’s inherited the mantle of Schattenjäger — “Shadow Hunter” — from his forefathers, and that his family’s legacy as battlers of evil stretches back to Medieval Germany. (The symbolism of his name is, as Jensen herself admits, not terribly subtle: “Gabriel” was the angel who battled Lucifer in Paradise Lost, while “Knight” means that he’s, well, a knight, at least in the metaphorical sense.) After ten days jam-packed with activity, which take him not only all around New Orleans but to Germany and Benin as well — Sins of the Fathers is a very generous game indeed in terms of length — Gabriel must choose between his love for Malia and his new role of Schattenjäger. Grace is around throughout: to serve as the good-girl contrast to the sultry Malia (again, the symbolism of her name isn’t subtle), to provide banter and research, and to pull Gabriel’s ass bodily out of the fire at least once. If Gabriel makes the right choice at the end of the game, the two forge a tentative partnership to continue the struggle against darkness even as they also continue to deny their true feelings for one another.

As we delve into what the game does well and poorly amidst all this, it strikes me as useful to break the whole edifice down along the classic divide of its interactivity versus its fiction. (If you’re feeling academic, you can refer to this dichotomy as its ludological versus its narratological components; if you’re feeling folksy, you can call it its crossword versus its narrative.) Even many of the game’s biggest fans will admit that the first item in the pairing has its problematic aspects. So, perhaps we should start there rather than diving straight into some really controversial areas. That said, be warned that the two things are hard to entirely separate from one another; Sins of the Fathers works best when the two are in harmony, while many of its problems come to the fore when the two begin to clash.

Let’s begin, though, with the things Sins of the Fathers gets right in terms of design. While I don’t know that it is, strictly speaking, impossible to lock yourself out of victory while still being able to play on, you certainly would have to be either quite negligent or quite determined to manage it at any stage before the endgame. This alone shows welcome progress for Sierra — shows that the design revolution wrought by LucasArts’s The Secret of Monkey Island was finally penetrating even this most stalwart redoubt of the old, bad way of making adventure games.

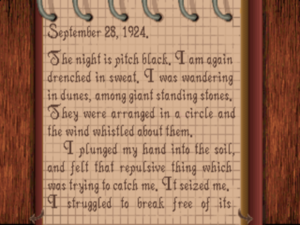

Snarking aside, we shouldn’t dismiss Jensen’s achievement here; it’s not easy to make such an intricately plot-driven game so forgiving. The best weapon in her arsenal is the use of an event-driven rather than a clock-driven timetable for advancing the plot. Each of the ten days has a set of tasks you must accomplish before the day ends, although you aren’t explicitly told what they are. You have an infinite amount of clock time to accomplish these things at your own pace. When you eventually do so — and even sometimes when you accomplish intermediate things inside each day — the plot machinery lurches forward another step or two via an expository cut scene and the interactive world around you changes to reflect it. Sins of the Fathers was by no means the first game to employ such a system; as far as I know, that honor should go to Infocom’s 1986 text adventure Ballyhoo. Yet this game uses it to better effect than just about any game that came before it. In fact, the game as a whole is really made tenable only by this technique of making the plot respond to the player’s actions rather than forcing the player to race along at the plot’s pace; the latter would be an unimaginable nightmare to grapple with in a story with this many moving parts. When it works well, which is a fair amount of the time, the plot progression feels natural and organic, like you truly are in the grip of a naturally unfolding story.

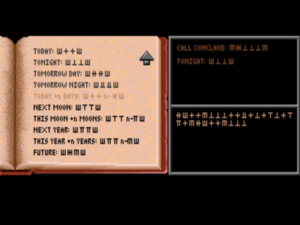

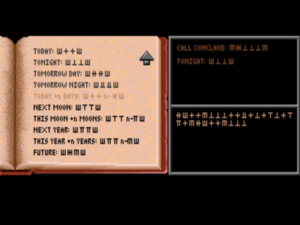

The individual puzzles that live within this framework work best when they’re in harmony with the plot and free of typical adventure-game goofiness. A good example is the multi-layered puzzle involving the Haitian rada drummers whom you keep seeing around New Orleans. Eventually, a victim of the voodoo cult tells you just before he breathes his last that the drummers are the cult’s means of communicating with one another across the city. So, you ask Grace to research the topic of rada drums. Next day, she produces a book on the subject filled with sequences encoding various words and phrases. When you “use” this book on one of the drummers, it brings up a sort of worksheet which you can use to figure out what he’s transmitting. Get it right, and you learn that a conclave is to be held that very night in a swamp outside the city.

Working out a rada-drum message.

This is an ideal puzzle: complicated but not insurmountable, immensely satisfying to solve. Best of all, solving it really does make you feel like Gabriel Knight, on the trail of a mystery which you must unravel using your own wits and whatever information you can dig up from the resources at your disposal.

Unfortunately, not all or even most of the puzzles live up to that standard. A handful are simply bad puzzles, full stop, testimonies both to the fact that every puzzle is always harder than its designer thinks it is and to Sierra’s disinterest in seeking substantive feedback on its games from actual players before releasing them. For instance, there’s the clock/lock that expects you to intuit the correct combination of rotating face and hands from a few scattered, tangential references elsewhere in the game to the number three and to dragons.

Even the rather brilliant rada-drums bit goes badly off the rails at the end of the game, when you’re suddenly expected to use a handy set of the drums to send a message of your own. This requires that you first read Jane Jensen’s mind to figure out what general message out of the dozens of possibilities she wants you to send, then read her mind again to figure out the exact grammar she wants you to use. When you get it wrong, as you inevitably will many times, the game gives you no feedback whatsoever. Are you doing the wrong thing entirely? Do you have the right idea but are sending the wrong message? Or do you just need to change up your grammar a bit? The game isn’t telling; it’s too busy killing you on every third failed attempt.

Other annoyances are the product not so much of poor puzzle as poor interface design. In contrast to contemporaneous efforts from competitors like LucasArts and Legend Entertainment, Sierra games made during this period still don’t show hot spots ripe for interaction when you mouse over a scene. So, you’re forced to click on everything indiscriminately, which most of the time leads only to the narrator intoning the same general room description over and over in her languid Caribbean patois. The scenes themselves are well-drawn, but their muted colors, combined with their relatively low resolution and the lack of a hot-spot finder, constitute something of a perfect storm for that greatest bane of the graphic adventure, the pixel hunt. One particularly egregious example of the syndrome, a snake scale you need to find at a crime scene on a beach next to Lake Pontchartrain, has become notorious as an impediment that stops absolutely every player in her tracks. It reveals the dark flip side of the game’s approach to plot chronology: that sinking feeling when the day just won’t end and you don’t know why. In this case, it’s because you missed a handful of slightly discolored pixels surrounded by a mass of similar hues — or, even if you did notice them, because you failed to click on them exactly.

You have to click right where the cursor is to learn from the narrator that “the grass has a matted appearance there.” Break out the magnifying glass!

But failings like these aren’t ultimately the most interesting to talk about, just because they were so typical and so correctable, had Sierra just instituted a set of commonsense practices that would have allowed them to make better games. Much more interesting are the places that the interactivity of Sins of the Fathers clashes jarringly with the premise of its fiction. For it’s here, we might speculate, that the game is running into more intractable problems — perhaps even running headlong into the formal limitation of the traditional graphic adventure as a storytelling medium.

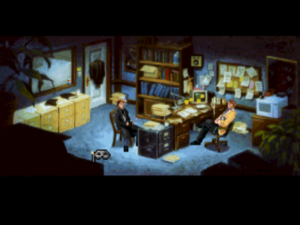

Take, for example, the point early in the game when Gabriel wants to pay a visit to Malia at her palatial mansion, but, as a mere civilian, can’t get past the butler. Luckily, he happens to have a pal at the police department — in fact, his best friend in the whole world, an old college buddy named Mosely. Does he explain his dilemma to Mosely and ask for help? Of course not! This is, after all, an adventure game. He decides instead to steal Mosely’s badge. When he pays the poor fellow a visit at his office, he sees that Mosely’s badge is pinned, as usual, to his jacket. So, Gabriel sneaks over to turn up the thermostat in the office, which causes Mosely to remove the jacket and hang it over the back of his chair. Then Gabriel asks him to fetch a cup of coffee, and completes the theft while he’s out of the room. With friends like that…

Gabriel is turned away from Malia’s door…

…but no worries, he can just figure out how to steal a badge from his best friend and get inside that way.

In strictly mechanical terms, this is actually a clever puzzle, but it illustrates the tonal and thematic inconsistencies that dog the game as a whole. Sadly, puzzles like the one involving the rada drums are the exception rather than the rule. Most of the time, you’re dealing instead with arbitrary roadblocks like this one that have nothing whatsoever to do with the mystery you’re trying to solve. It becomes painfully obvious that Jensen wrote out a static story outline suitable for a movie or novel, then went back to devise the disconnected puzzles that would make a game out of it.

But puzzles like this are not only irrelevant: they’re deeply, comprehensively silly, and this silliness flies in the face of Sins of the Fathers‘s billing as a more serious, character-driven sort of experience than anything Sierra had done to date. Really, how can anyone take a character who goes around doing stuff like this seriously? You can do so, I would submit, only by mentally bifurcating the Gabriel you control in the interactive sequences from the Gabriel of the cut scenes and conversations. That may work for some — it must, given the love that’s lavished on this game by so many adventure fans — but the end result nevertheless remains creatively compromised, two halves of a work of art actively pulling against one another.

Gabriel sneaks into the backroom of a church and starts stealing from the priests. That’s normal behavior for any moodily romantic protagonist, right? Right?

It’s at points of tension like these that Sins of the Fathers raises the most interesting and perhaps troubling questions about the graphic adventure as a genre. Many of its puzzles are, as I already noted, not bad puzzles in themselves; they’re only problematic when placed in this fictional context. If Sins of the Fathers was a comedy, they’d be a perfectly natural fit. This is what I mean when I say, as I have repeatedly in the past, that comedy exerts a strong centrifugal pull on any traditional puzzle-solving adventure game. And this is why most of Sierra’s games prior to Sins of the Fathers were more or less interactive cartoons, why LucasArts strayed afield from that comfortable approach even less often than Sierra, and, indeed, why comedies have been so dominant in the annals of adventure games in general.

The question must be, then, whether the pull of comedy can be resisted — whether compromised hybrids like this one are the necessary end result of trying to make a serious graphic adventure. In short, is the path of least resistance the only viable path for an adventure designer?

For my part, I believe the genre’s tendency to collapse into comedy can be resisted, if the designer is both knowing and careful. The Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes, released the year before Sins of the Fathers, is a less heralded game than the one I write about today, but one which works better as a whole in my opinion, largely because it sticks to its guns and remains the type of fiction it advertises itself to be, eschewing goofy roadblock puzzles in favor of letting you solve the mystery at its heart. By contrast, you don’t really solve the mystery for yourself at all in Sins of the Fathers; it solves the mystery for you while you’re jumping Gabriel through all the irrelevant hoops it sets in his path.

But let’s try to set those issues aside now and engage with Sins of the Fathers strictly in terms of the fiction that lives outside the lines of its interactivity. As many of you doubtless know, I’m normally somewhat loathe to do that; it verges on a tautology to say that interactivity is the defining feature of games, and thus it seems to me that any given game’s interactivity has to work, without any qualifiers, as a necessary precondition to its being a good game. Still, if any game might be able to sneak around that rule, it ought to be this one, so often heralded as a foremost exemplar of sophisticated storytelling in a ludic context. And, indeed, it does fare better on this front in my eyes — not quite as well as some of its biggest fans claim, but better.

The first real scene of Sins of the Fathers tells us we’re in for an unusual adventure-game experience, with unusual ambitions in terms of character and plot development alike. We meet Gabriel and Grace in medias res, as the former stumbles out of his backroom bedroom to meet the latter already at her post behind the cash register in the bookstore. Over the next couple of minutes, we learn much about them as people through their banter — and, tellingly, pretty much nothing about what the real plot of the game will come to entail. This is Bilbo holding his long-expected party, Wart going out to make hay; Jane Jensen is settling in to work the long game.

As Jensen slowly pulls back the curtain on what the game is really all about over the hours that follow, she takes Gabriel through that greatest rarity in interactive storytelling, a genuine internal character arc. The Gabriel at the end of the game, in other words, is not the one we met at the beginning, and for once the difference isn’t down to his hit points or armor class. If we can complain that we’re mostly relegated to solving goofy puzzles while said character arc plays out in the cut scenes, we can also acknowledge how remarkable it is for existing at all.

Jensen is a talented writer with a particular affinity for just the sort of snappy but revealing dialog that marks that first scene of the game. If anything, she’s better at writing these sorts of low-key “hang-out” moments than the scenes of epic confrontation. It’s refreshing to see a game with such a sense of ease about its smaller moments, given that the talents and interests of most game writers tend to run in just the opposite direction.

Then, too, Jensen has an intuitive understanding of the rhythm of effective horror. As any master of the form from Stephen King to the Duffer Brothers will happily tell you if you ask them, you can’t assault your audience with wall-to-wall terror. Good horror is rather about tension and release — the horrific crescendos fading into moments of calm and even levity, during which the audience has a chance to catch its collective breath and the knots in their stomachs have a chance to un-clench. Certainly we have to learn to know and like a story’s characters before we can feel vicarious horror at their being placed in harm’s way. Jensen understands all these things, as do the people working with her.

Indeed, the production values of Sins of the Fathers are uniformly excellent in the context of its times. The moody art perfectly complements the story Jensen has scripted, and the voice-acting cast — both the big names who head it and the smaller ones who fill out the rest of the roles — are, with only one or two exceptions, solid. The music, which was provided by the project’s producer Robert Holmes — he began dating Jensen while the game was in production, and later became her husband and constant creative partner — is catchy, memorable, and very good at setting the mood, if perhaps not hugely New Orleans in flavor. (More on that issue momentarily.)

Still, there are some significant issues with Sins of the Fathers even when it’s being judged purely as we might a work of static fiction. Many of these become apparent only gradually over time — this is definitely a game that puts its best foot forward first — but at least one of them is front and center from the very first scene. To say that much of Gabriel’s treatment of Grace hasn’t aged well hardly begins to state the case. Their scenes together often play like a public-service video from the #MeToo movement, as Gabriel sexually harasses his employee like Donald Trump with a fresh bottle of Viagra in his back pocket. Of course, Jensen really intends for Gabriel to be another instance of the archetypal charming rogue — see Solo, Han, and Jones, Indiana — and sometimes she manages to pull it off. At far too many others, though, the writing gets a little sideways, and the charming rogue veers into straight-up jerk territory. The fact that Grace is written as a smart, tough-minded young woman who can give as good as she gets doesn’t make him seem like any less of a sleazy creep, more Leisure Suit Larry than James Dean.

I’m puzzled and just a little bemused that so many academic writers who’ve taken it upon themselves to analyze the game from an explicitly feminist perspective can ignore this aspect of it entirely. I can’t help but suspect that, were Sins of the Fathers the product of a male designer, the critical dialog that surrounds it would be markedly different in some respects. I’ll leave it to you to decide whether this double standard is justified or not in light of our culture’s long history of gender inequality.

As the game continues, the writing starts to wear thin in other ways. Gabriel’s supposed torrid love affair with Malia is, to say the least, unconvincing, with none of the naturalism that marks the best of his interactions with Grace. Instead it’s in the lazy mold of too many formulaic mass-media fictions, where two attractive people fall madly in love for no discernible reason that we can identify. The writer simply tells us that they do so, by way of justifying an obligatory sex scene or two. Here, though, we don’t even get the sex scene.

Pacing also starts to become a significant problem as the game wears on. Admittedly, this is not always so much because the writer in Jane Jensen isn’t aware of its importance to effective horror as because pacing in general is just so darn difficult to control in any interactive work, especially one filled with road-blocking puzzles like this one. Even if we cut Jensen some slack on this front, however, sequences like Gabriel’s visit to Tulane University, where he’s subjected to a long non-interactive lecture that might as well be entitled “Everything Jane Jensen Learned about Voodoo but Can’t Shoehorn in Anywhere Else,” are evidence of a still fairly inexperienced writer who doesn’t have a complete handle on this essential element of storytelling and doesn’t have anyone looking over her shoulder to edit her work. She’s done her research, but hasn’t mastered the Zen-like art of letting it subtly inform her story and setting. Instead she infodumps it all over us in about the most unimaginative way you can conceive: in the form of a literal classroom lecture.

Gabriel with Professor Infodump.

The game’s depiction of New Orleans itself reveals some of the same weaknesses. Yes, Jensen gets the landmarks and the basic geography right. But I have to say, speaking as someone who loves the city dearly and has spent a fair amount of time there over the years, that the setting of the game never really feels like New Orleans. What’s missing most of all, I think, is any affinity for the music that so informs daily life in the city, giving the streets a (literal) rhythm unlike anywhere else on earth. (Robert Holmes’s soundtrack is fine and evocative in its own right; it’s just not a New Orleans soundtrack.) I was thus unsurprised to learn that Jensen never actually visited New Orleans before writing and publishing a game set there. Tellingly, her depiction has more to do with the idiosyncratic, Gothic New Orleans found in Anne Rice novels than it does with the city I know.

The plotting too gets more wobbly as time goes on. A linchpin moment comes right at the mid-point of the ten days, when Gabriel makes an ill-advised visit to one of the cult’s conclaves — in fact, the one he located via the afore-described rada-drums puzzle — and nearly gets himself killed. Somehow Grace, of all people, swoops in to rescue him; I still have no idea precisely what is supposed to have happened here, and neither, judging at least from the fan sites I’ve consulted, does anyone else. I suspect that something got cut here out of budget concerns, so perhaps it’s unfair to place this massive non sequitur at the heart of the game squarely on Jensen’s shoulders.

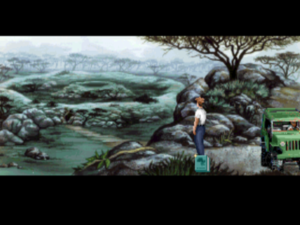

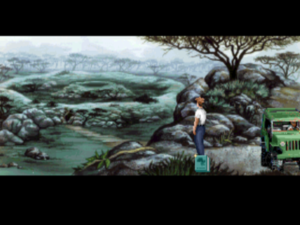

But other problems with the plotting aren’t as easy to find excuses for. There is, for example, the way that Gabriel can fly from New Orleans to Munich and still have hours of daylight at his disposal when he arrives on the same day. (I could dismiss this as a mere hole in Jensen’s research, the product of an American designer unfamiliar with international travel, if she hadn’t spent almost a year living in Germany prior to coming to Sierra.) In fact, the entirety of Gabriel’s whirlwind trip from the United States to Germany to Benin and back home again feels incomplete and a little half-baked, from its cartoonish German castle, which resembles a piece of discarded art from a King’s Quest game, to its tedious maze inside an uninteresting African burial mound that likewise could have been found in any of a thousand other adventure games. Jensen would have done better to keep the action in New Orleans rather than suddenly trying to turn the game into a globetrotting adventure at the eleventh hour, destroying its narrative cohesion in the process.

Suddenly we’re in… Africa? How the hell did that happen?

As in a lot of fictions of this nature, the mysteries at the heart of Sins of the Fathers are also most enticing in the game’s earlier stages than they have become by its end. To her credit, Jensen knows exactly what truths lie behind all of the mysteries and deceptions, and she’s willing to show them to us; Sins of the Fathers does have a payoff. Nevertheless, it’s all starting to feel a little banal by the time we arrive at the big climax inside the voodoo cult’s antiseptic high-tech headquarters. It’s easier to be scared of shadowy spirits of evil from the distant past than it is of voodoo bureaucrats flashing their key cards in a complex that smacks of a Bond villain’s secret hideaway.

The tribal art on the wall lets you know this is a voodoo cult’s headquarters. Somehow I never expected elevators and fluorescent lighting in such a place…

Many of you — especially those of you who count yourselves big fans of Sins of the Fathers — are doubtless saying by now that I’m being much, much too hard on it. And you have a point; I am holding this game’s fiction to a higher standard than I do that of most adventure games. In a sense, though, the game’s very conception of itself makes it hard for a critic to avoid doing so. It so clearly wants to be a more subtle, more narratively and thematically rich, more “adult” adventure game that I feel forced to take it at its word and hold it to that higher standard. One could say, then, that the game becomes a victim of its own towering ambitions. Certainly all my niggling criticisms shouldn’t obscure the fact that, for all that its reach does often exceed its grasp, it’s brave of the game to stretch itself so far at all.

That said, I can’t help but continue to see Sins of the Fathers more as a noble failure than a masterpiece, and I can’t keep myself from placing much of the blame at the feet of Sierra rather than Jane Jensen per se. I played it most recently with my wife, as I do many of the games I write about here. She brings a valuable perspective because she’s much, much smarter than I am but couldn’t care less about where, when, or whom the games we play came from; they’re strictly entertainments for her. At some point in the midst of playing Sins of the Fathers, she turned to me and remarked, “This would probably have been a really good game if it had been made by that other company.”

I could tell I was going to have to dig a bit to ferret out her meaning: “What other company?”

“You know, the one that made that time-travel game we played with the really nerdy guy and that twitchy girl, and the one about the dog and the bunny. I think they would have made sure everything just… worked better. You know, fixed all of the really irritating stuff, and made sure we didn’t have to look at a walkthrough all the time.”

That “other company” was, of course, LucasArts.

One part of Sins of the Fathers in particular reminds me of the differences between the two companies. There comes a point where Gabriel has to disguise himself as a priest, using a frock stolen from St. Louis Cathedral and some hair gel from his own boudoir, in order to bilk an old woman out of her knowledge of voodoo. This is, needless to say, another example of the dissonance between the game’s serious plot and goofy puzzles, but we’ve covered that ground already. What’s more relevant right now is the game’s implementation of the sequence. Every time you visit the old woman — which will likely be several times if you aren’t playing from a walkthrough — you have to laboriously prepare Gabriel’s disguise all over again. It’s tedium that exists for no good reason; you’ve solved the puzzle once, and the game ought to know you’ve solved it, so why can’t you just get on with things? I can’t imagine a LucasArts game subjecting me to this. In fact, I know it wouldn’t: there’s a similar situation in Day of the Tentacle, where, sure enough, the game whips through the necessary steps for you every time after the first.

Father Gabriel. (Sins of the fathers indeed, eh?)

This may seem a small, perhaps even petty example, but, multiplied by a hundred or a thousand, it describes why Sierra adventures — even their better, more thoughtful efforts like this one — so often wound up more grating than fun. Sins of the Fathers isn’t a bad adventure game, but it could have been so much better if Jensen had had a team around her armed with the development methodologies and testing processes that could have eliminated its pixel hunts, cleaned up its unfair and/or ill-fitting puzzles, told her when Gabriel was starting to sound more like a sexual predator than a laid-back lady’s man, and smoothed out the rough patches in its plot. None of the criticisms I’ve made of the game should be taken as a slam against Jensen, a writer with special gifts in exactly those areas where other games tend to disappoint. She just didn’t get the support she needed to reach her full potential here.

The bitter irony of it all is that LucasArts, a company that could have made Sins of the Fathers truly great, lacked the ambition to try anything like it in lieu of the cartoon comedies which they knew worked for them; meanwhile Sierra, a company with ambition in spades, lacked the necessary commitment to detail and quality. I really don’t believe, in other words, that Sins of the Father represents some limit case for the point-and-click adventure as a storytelling medium. I think merely that it represents, like all games, a grab bag of design choices, some of them more felicitous than others.

Still, if what we ended up with is the very definition of a mixed bag, it’s nevertheless one of the most interesting and important such in the history of adventure games, a game whose influence on what came later, both inside and outside of its genre, has been undeniable. I know that when I made The King of Shreds and Patches, my own attempt at a lengthy horror adventure with a serious plot, Sins of the Fathers was my most important single ludic influence, providing a bevy of useful examples both of what to do and what not to do. (For instance, I copied its trigger-driven approach to plot chronology — but I made sure to include a journal to tell the player what issues she should be working on at any given time, thereby to keep her from wandering endlessly looking for the random whatsit that would advance the time.) I know that many other designers of much more prominent games than mine have also taken much away from Sins of the Fathers.

So, should you play Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers? Absolutely. It’s a fascinating example of storytelling ambition in games, and, both in where it works and where it fails, an instructive study in design as well. A recent remake helmed by Jane Jensen herself even fixes some of the worst design flaws, although not without considerable trade-offs: the all-star cast of the original game has been replaced with less distinctive voice acting, and the new graphics, while cleaner and sharper, don’t have quite the same moody character as the old. Plague or cholera; that does seem to be the way with adventure games much of the time, doesn’t it? With this game, one might say, even more so than most of them.

The big climax. Yes, it does look a little ridiculous — but hey, they were trying.

(Sources: the book Influential Game Designers: Jane Jensen by Anastasia Salter; Sierra’s newsletter InterAction of Spring 1992, Summer 1993, and Holiday 1993; Computer Gaming World of November 1993 and March 1994. Online sources include “The Making of… The Gabriel Knight Trilogy” from Edge Online; an interview with Jane Jensen done by the old webzine The Inventory, now archived at The Gabriel Knight Pages; “Happy Birthday, Gabriel Knight“ from USgamer; Jane Jensen’s “Ask Me Anything” on Reddit. Academic pieces include “Revisiting Gabriel Knight” by Connie Veugen from The Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet Volume 7; Jane Jensen’s Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers: The Numinous Woman and the Millennium Woman” by Roberta Sabbath from The Journal of Popular Culture Volume 31 Issue 1. And, last but not least, press releases, annual reports, and other internal and external documents from the Sierra archive at the Strong Museum of Play.

Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers is available for purchase both in its original version and as an enhanced modern remake.)