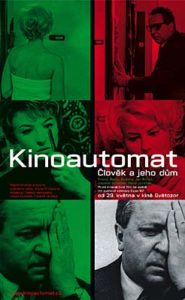

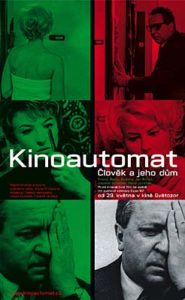

Over the course of six months in 1967, 50 million people visited Expo ’67 in Montreal, one of the most successful international exhibitions in the history of the world. Representatives from 62 nations set up pavilions there, showcasing the cutting edge in science, technology, and the arts. The Czechoslovakian pavilion was a surprisingly large one, with a “fairytale area” for children, a collection of blown Bohemian glassware, a “Symphony of Developed Industry,” and a snack bar offering “famous Pilsen beer.” But the hit of the pavilion — indeed, one of the sleeper hits of the Expo as a whole — was to be found inside a small, nondescript movie theater. It was called Kinoautomat, and it was the world’s first interactive movie.

Visitors who attended a screening found themselves ushered to seats that sported an unusual accessory: large green and red buttons mounted to the seat backs in front of them. The star of the film, a well-known Czech character actor named Miroslav Horníček, trotted onto the tiny stage in front of the screen to explain that the movie the visitors were about to see was unlike any they had ever seen before. From time to time, the action would stop and he would pop up again to let the audience decide what his character did next onscreen. Each audience member would register which of the two choices she preferred by pressing the appropriate button, the results would be tallied, and simple majority rule would decide the issue.

As a film, Kinoautomat is a slightly risqué but otherwise harmless farce. The protagonist, a Mr. Novak, has just bought some flowers to give to his wife — it’s her birthday today — and is waiting at home for her to return to their apartment when his neighbor’s wife, an attractive young blonde, accidentally locks herself out of her own apartment with only a towel on. She frantically bangs on Mr. Novak’s door, putting him in an awkward position and presenting the audience with their first choice. Should he let her in and try to explain the presence of a naked woman in their apartment to his wife when she arrives, or should he refuse the poor girl, leaving her to shiver in the altogether in the hallway? After this first choice is made, another hour or so of escalating misunderstanding and mass confusion ensues, during which the audience is given another seven or so opportunities to vote on what happens next.

Kinoautomat played to packed houses throughout the Expo’s run, garnering heaps of press attention in the process. Radúz Činčera, the film’s director and the entire project’s mastermind, was lauded for creating what was called by some critics one of the boldest innovations in the history of cinema. After the Expo was over, Činčera’s interactive movie theater was set up several more times in several other cities, always with a positive response, and Hollywood tried to open a discussion about licensing the technology behind it. But the interest and exposure gradually dissipated, perhaps partly due to a crackdown on “decadent” art by Czechoslovakia’s ruling Communist Party, but almost certainly due in the largest part to the logistical challenges involved in setting up the interactive movie theaters that were needed to show it. It was last shown at Expo ’74 in Spokane, Washington, after which it disappeared from screens and memories for more than two decades, to be rescued from obscurity only well into the 1990s, after the Iron Curtain had been thrown open, when it was stumbled upon once again by some of the first academics to study seriously the nature of interactivity in digital mediums.

Had Činčera’s experiment been better remembered at the beginning of the 1990s, it might have saved a lot of time for those game developers dreaming of making interactive movies on personal computers and CD-ROM-based set-top boxes. Sure, the technology Činčera had to work with was immeasurably more primitive; his branching narrative was accomplished by the simple expedient of setting up two film projectors at the back of the theater and having an attendant place a lens cap over whichever held the non-applicable reel. Yet the more fundamental issues he wrestled with — those of how to create a meaningfully interactive experience by splicing together chunks of non-interactive filmed content — remained unchanged more than two decades later.

The dirty little secret about Kinoautomat was that the interactivity in this first interactive film was a lie. Each branch the story took contrived only to give lip service to the audience’s choice, after which it found a way to loop back onto the film’s fixed narrative through-line. Whether the audience was full of conscientious empathizers endeavoring to make the wisest choices for Mr. Novak or crazed anarchists trying to incite as much chaos as possible — the latter approach, for what it’s worth, was by far the more common — the end result would be the same: poor Mr. Novak’s entire apartment complex would always wind up burning to the ground in the final scenes, thanks to a long chain of happenstance that began with that naked girl knocking on his door. Činčera had been able to get away with this trick thanks to the novelty of the experience and, most of all, thanks to the fact that his audience, unless they made the effort to come back more than once or to compare detailed notes with those who had attended other screenings, was never confronted with how meaningless their choices actually were.

While it had worked out okay for Kinoautomat, this sort of fake interactivity wasn’t, needless to say, a sustainable path for building the whole new interactive-movie industry — a union of Silicon Valley and Hollywood — which some of the most prominent names in the games industry were talking of circa 1990. At the same time, though, the hard reality was that to create an interactive movie out of filmed, real-world content that did offer genuinely meaningful, story-altering branches seemed for all practical purposes impossible. The conventional computer graphics that had heretofore been used in games, generated by the computer and drawn on the screen programmatically, were a completely different animal than the canned snippets of video which so many were now claiming would mark the proverbial Great Leap Forward. Conventional computer graphics could be instantly, subtly, and comprehensively responsive to the player’s actions. The snippets in what the industry would soon come to call a “full-motion-video” game could be mixed and matched and juggled, but only in comparatively enormous static chunks.

This might not sound like an impossible barrier in and of itself. Indeed, the medium of textual interactive fiction had already been confronted with seemingly similar contrasts in granularity between two disparate approaches which had both proved equally viable. As I’ve had occasion to discuss in an earlier article, a hypertext narrative built out of discrete hard branches is much more limiting in some ways than a parser-driven text adventure with its multitudinous options available at every turn — but, importantly, the opposite is also true. A parser-driven game that’s forever fussing over what room the player is standing in and what she’s carrying with her at any given instant is ill-suited to convey large sweeps of time and plot. Each approach, in other words, is best suited for a different kind of experience. A hypertext narrative can become a wide-angle exploration of life-changing choices and their consequences, while the zoomed-in perspective of the text adventure is better suited to puzzle-solving and geographical exploration — that is, to the exploration of a physical space rather than a story space.

And yet if we do attempt to extend a similar comparison to a full-motion-video adventure game versus one built out of conventional computer graphics, it may hold up in the abstract, but quickly falls apart in the realm of the practical and the specific. Although the projects exploring full-motion-video applications were among the most expensive the games industry of 1990 had ever funded, their budgets paled next to those of even a cheap Hollywood production. To produce full-motion-video games with meaningfully branching narratives would require their developers to stretch their already meager budgets far enough to shoot many, many non-interactive movies in order to create a single interactive movie, accepting that the player would see only a small percentage of all those hours of footage on any given play-through. And even assuming that the budget could somehow be stretched to allow such a thing, there were other practical concerns to reckon with; after all, even the wondrous new storage medium of CD-ROM had its limits in terms of capacity.

Faced with these issues, would-be designers of full-motion-video games did what all game designers do: they worked to find approaches that — since there was no way to bash through the barriers imposed on them — skirted around the problem.

They did have at least one example to follow or reject — one that, unlike Kinoautomat, virtually every working game designer knew well. Dragon’s Lair, the biggest arcade hit of 1983, had been built out of a chopped-up cartoon which un-spooled from a laser disc housed inside the machine. It replaced all of the complications of branching plots with a simple do-or-die approach. The player needed to guide the joystick through just the right pattern of rote movements — a pattern identifiable only through extensive trial and error — in time with the video playing on the screen. Failure meant death, success meant the cartoon continued to the next scene — no muss, no fuss. But, as the many arcade games that had tried to duplicate Dragon’s Lair‘s short-lived success had proved, it was hardly a recipe for a satisfying game once the novelty wore off.

Another option was to use full-motion video for cut scenes rather than as the real basis of a game, interspersing static video sequences used for purposes of exposition in between interactive sequences powered by conventional computer graphics. In time, this would become something of a default approach to the problem of full-motion video, showing up in games as diverse as the Wing Commander series of space-combat simulators, the Command & Conquer real-time strategy series, and even first-person shooters like Realms of the Haunting. But such juxtapositions would always be doomed to look a little jarring, the ludic equivalent of an animated film which from time to time switches to live action for no aesthetically valid reason. As such, this would largely become the industry’s fallback position, the way full-motion video wound up being deployed as a last resort after designers had failed to hit upon a less jarring formula. Certainly in the early days of full-motion video — the period we’re interested in right now — there still remained the hope that some better approach to the melding of computer game and film might be discovered.

The most promising approaches — the ones, that is, that came closest to working — often used full-motion video in the context of a computerized mystery. In itself, this is hardly surprising. Despite the well-known preference of gamers and game designers for science-fiction and fantasy scenarios, the genre of traditional fiction most obviously suited for ludic adaptation is in fact the classic mystery novel, the only literary genre that actively casts itself as a sort of game between writer and reader. A mystery novel, one might say, is really two stories woven together. One is that of the crime itself, which is committed before the book proper really gets going. The other is that of the detective’s unraveling of the crime; it’s here, of course, that the ludic element comes in, as the reader too is challenged to assemble the clues alongside the detective and try to deduce the perpetrator, method, and motive before they are revealed to her.

For a game designer wrestling with the challenges inherent in working with full-motion video, the advantages of this structure count double. The crime itself is that most blessed of things for a designer cast adrift on a sea of interactivity: a fixed story, an unchanging piece of solid narrative ground. In the realm of interactivity, then, the designer is only forced to deal with the investigation, a relatively circumscribed story space that isn’t so much about making a story as uncovering one that already exists. The player/detective juggles pieces of that already extant story, trying to slot them together to make the full picture. In that context, the limitations of full-motion video — all those static chunks of film footage that must be mixed and matched — suddenly don’t sound quite so limiting. Full-motion video, an ill-fitting solution that has to be pounded into place with a sledgehammer in most interactive applications, suddenly starts seeming like an almost elegant fit.

The origin story of the most prominent of the early full-motion-video mysteries, a product at the bleeding edge of technology at the time it was introduced, ironically stretches back to a time before computers were even invented. In 1935, J.G. Links, a prominent London furrier, came up with an idea to take the game-like elements of the traditional mystery novel to the next level. What if a crime could be presented to the reader not as a story about its uncovering but in a more unprocessed form, as a “dossier” of clues, evidence, and suspects? The reader would be challenged to assemble this jigsaw into a coherent description of who, what, when, and where. Then, when she thought she was ready, she could open a sealed envelope containing the solution to find out if she had been correct. Links pitched the idea to a friend of his who was well-positioned to see it through with him: Dennis Wheatley, a very popular writer of crime and adventure novels. Together Links and Wheatley created four “Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers,” which enjoyed considerable success before the undertaking was stopped short by the outbreak of World War II. After the war, mysteries in game form drifted into the less verisimilitudinous but far more replayable likes of Cluedo, while non-digital interactive narratives moved into the medium of experiential wargames, which in turn led, in time, to the great tabletop-gaming revolution that was Dungeons & Dragons.

And that could very well have been the end of the story, leaving the Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers as merely a road not taken in game history, works ahead of their time that wound up getting stranded there. But in 1979 Mayflower Books began republishing the dossiers, a complicated undertaking that involved recreating the various bits of “physical evidence” — including pills, fabric samples, cigarette butts, and even locks of hair — that had accompanied them. There is little indication that their efforts were rewarded with major sales. Yet, coming as they did at a fraught historical moment for interactive storytelling in general — the first Choose Your Own Adventure book was published that same year; the game Adventure had hit computers a couple of years before; Dungeons & Dragons was breaking into the mainstream media — the reprinted dossiers’ influence would prove surprisingly pervasive with innovators in the burgeoning field. They would, for instance, provide Marc Blank with the idea of making a sort of crime dossier of his own to accompany Infocom’s 1982 computerized mystery Deadline, thereby establishing the Infocom tradition of scene-setting “feelies” and elaborate packaging in general. And another important game whose existence is hard to imagine without the example provided by the Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers appeared a year before Deadline.

Prior to the Mayflower reprints, the closest available alternative to the Crime Dossiers had been a 1975 Sherlock Holmes-starring board game called 221B Baker Street: The Master Detective Game. It plays like a more coherent version of Cluedo, thanks to its utilization of pre-crafted mysteries that are included in the box rather than a reliance on random combinations of suspects, locations, and weapons. Otherwise, however, the experience isn’t all that markedly different, with players rolling dice and moving their tokens around the game board, trying to complete their “solution checklists” before their rivals. The competitive element introduces a bit of cognitive dissonance that is never really resolved: this game of Sherlock Holmes actually features several versions of Holmes, all racing around London trying to solve each mystery before the others can. But more importantly, playing it still feels more like solving a crossword puzzle than solving a mystery.

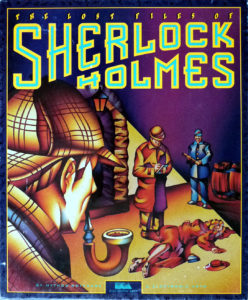

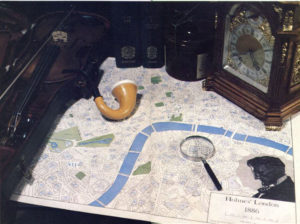

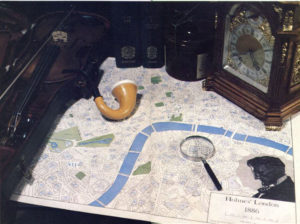

Two of those frustrated by the limitations of 221B Baker Street were Gary Grady and Suzanne Goldberg, amateur scholars of Sherlock Holmes living in San Francisco. “A game like 221B Baker Street doesn’t give a player a choice,” Grady noted. “You have no control over the clue you’re going to get and there’s no relationship of the clues to the process of play. We wanted the idea of solving a mystery rather than a puzzle.” In 1979, with the negative example of 221B Baker Street and the positive example of the Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers to light the way, the two started work on a mammoth undertaking that would come to be known as Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective upon its publication two years later. Packaged and sold as a board game, it in truth had much less in common with the likes of Cluedo or 221B Baker Street than it did with the Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers. Grady and Goldberg provided rules for playing competitively if you insisted, and a scoring system that challenged you to solve a case after collecting the least amount of evidence possible, but just about everyone who has played it agrees that the real joy of the game is simply in solving the ten labyrinthine cases, each worthy of an Arthur Conan Doyle story of its own, that are included in the box.

Each case is housed in a booklet of its own, whose first page or two sets up the mystery to be solved in rich prose that might indeed have been lifted right out of a vintage Holmes story. The rest of the booklet consists of more paragraphs to be read as you visit various locations around London, following the evidence trail wherever it leads. When you choose to visit someplace (or somebody), you look it up in the London directory that is included, which will give you a coded reference. If that code is included in the case’s booklet, eureka, you may just have stumbled upon more information to guide your investigation; at the very least, you’ve found something new to read. In addition to the case books, you have lovingly crafted editions of the London Times from the day of each case to scour for more clues; cleverly, the newspapers used for early cases can contain clues for later cases as well, meaning the haystack you’re searching for needles gets steadily bigger as you progress from case to case. You also have a map of London, which can become unexpectedly useful for tracing the movements of suspects. Indeed, each case forces you to apply a whole range of approaches and modes of thought to its solution. When you think you’re ready, you turn to the “quiz book” and answer the questions about the case therein, then turn the page to find out if you were correct.

If Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective presents a daunting challenge to its player, the same must go ten times over for its designers. The amount of effort that must have gone into creating, collating, intertwining, and typesetting such an intricate web of information fairly boggles the mind. The game is effectively ten Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers in one box, all cross-referencing one another, looping back on one another. That Grady and Goldberg, working in an era before computerized word processing was widespread, managed it at all is stunning.

Unable to interest any of the established makers of board games in such an odd product, the two published it themselves, forming a little company called Sleuth Publications for the purpose. A niche product if ever there was one, it did manage to attract a champion in Games magazine, who called it “the most ingenious and realistic detective game ever devised.” The same magazine did much to raise its profile when they added it to their mail-order store in 1983. A German translation won the hugely prestigious Spiel des Jahres in 1985, a very unusual selection for a competition that typically favored spare board games of abstract logic. Over the years, Sleuth published a number of additional case packs, along with another boxed game in the same style: Gumshoe, a noirish experience rooted in Raymond Chandler rather than Arthur Conan Doyle which was less successful, both creatively and commercially, than its predecessor.

And then these elaborate analog productions, almost defiantly old-fashioned in their reliance on paper and text and imagination, became the unlikely source material for the most high-profile computerized mysteries of the early CD-ROM era.

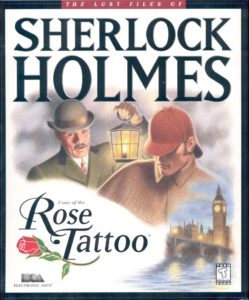

The transformation would be wrought by ICOM Simulations, a small developer who had always focused their efforts on emerging technology. They had first made their name with the release of Déjà Vu on the Macintosh in 1985, one of the first adventure games to replace the parser with a practical point-and-click interface; in its day, it was quite the technological marvel. Three more games built using the same engine had followed, along with ports to many, many platforms. But by the time Déjà Vu II hit the scene in 1988, the interface was starting to look a little clunky and dated next to the efforts of companies like Lucasfilm Games, and ICOM decided it was time to make a change — time to jump into the unexplored waters of CD-ROM and full-motion video. They had always been technophiles first, game designers second, as was demonstrated by the somewhat iffy designs of most of their extant games. It therefore made a degree of sense to adapt someone else’s work to CD-ROM. They decided that Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, that most coolly intellectual of mystery-solving board games, would counter-intuitively adapt very well to a medium that was supposed to allow hotter, more immersive computerized experiences than ever before.

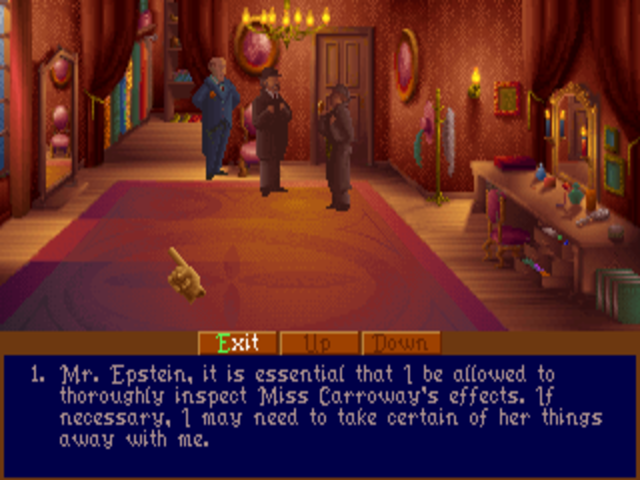

As we’ve already seen, the limitations of working with chunks of static text are actually very similar in some ways to those of working with chunks of static video. ICOM thus decided that the board game’s methods for working around those limitations should work very well for the computer game as well. The little textual vignettes which filled the case booklets, to be read as the player moved about London trying to solve the case, could be recreated by live actors. There would be no complicated branching narrative, just a player moving about London, being fed video clips of her interviews with suspects. Because the tabletop game included no mechanism for tracking where the player had already been and what she had done, the text in the case booklets had been carefully written to make no such presumptions. Again, this was perfect for a full-motion-video adaptation.

Gary Grady and Suzanne Goldberg were happy to license their work; after laboring all these years on such a complicated niche product, the day on which ICOM knocked on their door must have been a big one indeed. Ken Tarolla, the man who took charge of the project for ICOM, chose three of the ten cases from the original Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective to serve as the basis of the computer game. He now had to reckon with the challenges of going from programming games to filming them. Undaunted, he had the vignettes from the case booklets turned into scripts by a professional screenwriter, hired 35 actors to cast in the 50 speaking parts, and rented a sound stage in Minneapolis — far from ICOM’s Chicago offices, but needs must — for the shoot. The production wound up requiring 70 costumes along with 25 separate sets, a huge investment for a small developer like ICOM. In spite of their small size, they evinced a commitment to production values few of their peers could match. Notably, they didn’t take the money-saving shortcut of replacing physical sets with computer-generated graphics spliced in behind the actors. For this reason, their work holds up much better today than that of most of their peers.

Indeed, as befits a developer of ICOM’s established technical excellence — even if they were working in an entirely new medium — the video sequences are surprisingly good, the acting and set design about up to the standard of a typical daytime-television soap opera. If that seems like damning with faint praise, know that the majority of similar productions come off far, far worse. Peter Farley, the actor hired to play Holmes, may not be a Basil Rathbone, Jeremy Brett, or Benedict Cumberbatch, but neither does he embarrass himself. The interface is decent, and the game opens with a video tutorial narrated by Holmes himself — a clear sign of how hard Consulting Detective is straining to be the more mainstream, more casual form of interactive entertainment that the CD-ROM was supposed to precipitate.

First announced in 1990 and planned as a cross-platform product from the beginning, spanning the many rival CD-ROM initiatives on personal computers, set-top boxes, and game consoles, ICOM’s various versions of Consulting Detective were all delayed for long stretches by a problem which dogged every developer working in the same space: the struggle to find a way of getting video from CD-ROM to the screen at a reasonable resolution, frame rate, and number of colors. The game debuted in mid-1991 on the NEC TurboGrafx-16, an also-ran in the console wars which happened to be the first such device to offer a CD-ROM drive as an accessory. In early 1992, it made its way to the Commodore CDTV, thanks to a code library for video playback devised by Carl Sassenrath, long a pivotal figure in Amiga circles. Then, and most importantly in commercial terms, the slow advance of computing hardware finally made it possible to port the game to Macintosh and MS-DOS desktop computers equipped with CD-ROM drives later in the same year.

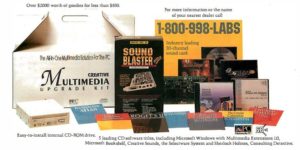

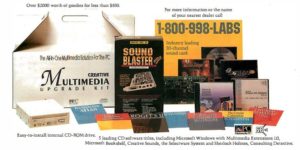

Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective became a common sight in “multimedia upgrade kits” like this one from Creative Labs.

As one of the first and most audiovisually impressive products of its kind, Consulting Detective existed in an uneasy space somewhere between game and tech demo. It was hard for anyone who had never seen actual video featuring actual actors playing on a computer before to focus on much else when the game was shown to them. It was therefore frequently bundled with the “multimedia upgrade kits,” consisting of a sound card and CD-ROM drive, that were sold by companies like Creative Labs beginning in 1992. Thanks to these pack-in deals, it shipped in huge numbers by conventional games-industry terms. Thus encouraged, ICOM went back to the well for a Consulting Detective Volume II and Volume III, each with another three cases from the original board game. These releases, however, did predictably less well without the advantages of novelty and of being a common pack-in item.

As I’ve noted already, Consulting Detective looks surprisingly good on the surface even today, while at the time of its release it was nothing short of astonishing. Yet it doesn’t take much playing time before the flaws start to show through. Oddly given the great care that so clearly went into its surface production, many of its problems feel like failures of ambition. As I’ve also already noted, no real state whatsoever is tracked by the game; you just march around London watching videos until you think you’ve assembled a complete picture of the case, then march off to trial, which takes the form of a quiz on who did what and why. If you go back to a place you’ve already been, the game doesn’t remember it: the same video clip merely plays again. This statelessness turns out to be deeply damaging to the experience. I can perhaps best explain by taking as an example the first case in the first volume of the series. (Minor spoilers do follow in the next several paragraphs. Skip down to the penultimate paragraph — beginning with “To be fair…” — to avoid them entirely.)

“The Mummy’s Curse” concerns the murder on separate occasions of all three of the archaeologists who have recently led a high-profile expedition to Egypt. One of the murders took place aboard the ship on which the expedition was returning to London, laden with treasures taken — today, we would say “looted” — from a newly discovered tomb. We can presume that one of the other passengers most likely did the deed. So, we acquire the passenger manifest for the ship and proceed to visit each of the suspects in turn. Among them are Mr. and Mrs. Fenwick, two eccentric members of the leisured class. Each of them claims not to have seen, heard, or otherwise had anything to do with the murder. But Louise Fenwick has a little dog, a Yorkshire terrier of whom she is inordinately fond and who traveled with the couple on their voyage. (Don’t judge the game too harshly from the excerpt below; it features some of the hammiest acting of all, with a Mrs. Fenwick who seems to be channeling Miss Piggy — a Miss Piggy, that is, with a fake English accent as horrid as only an American can make it.)

The existence of Mrs. Fenwick’s dog is very interesting in that the Scotland Yard criminologist who handled the case found some dog hair on the victim’s body. Our next natural instinct would be to find out whether the hair could indeed have come from a Yorkshire terrier — but revisiting Scotland Yard will only cause the video from there which we’ve already seen to play again. Thus stymied on that front, we probe further into Mrs. Fenwick’s background. We learn that the victim once gave a lecture before the Royal Society where he talked about dissecting his own Yorkshire terrier after its death, provoking the ire of the Anti-Vivisection League, of which Louise Fenwick is a member. And it gets still better: she personally harassed the victim, threatening to dissect him herself. Now, it’s very possible that this is all coincidence and red herrings, but it’s certainly something worth following up on. So we visit the Fenwicks again to ask her about it — and get to watch the video we already saw play again. Stymied once more.

This example hopefully begins to illustrate how Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective breaks its promise to let you be the detective and solve the crime yourself in the way aficionados of mystery novels had been dreaming of doing for a century. Because the game never knows what you know, and because it only lets you decide where you go, nothing about what you do after you get there, playing it actually becomes much more difficult than being a “real” detective. You’re constantly being hobbled by all these artificial constraints. Again and again, you find yourself seething because you can’t ask the question Holmes would most certainly be asking in your situation. It’s a form of fake difficulty, caused by the constraints of the game engine rather than the nature of the case.

Consider once more, then, how this plays out in practice in “The Mummy’s Curse.” We pick up this potentially case-cracking clue about Mrs. Fenwick’s previous relations with the victim. If we’ve ever read a mystery novel or watched a crime drama, we know immediately what to do. Caught up in the fiction, we rush back to the Fenwicks without even thinking about it. We get there, and of course it doesn’t work; we just get the same old spiel. It’s a thoroughly deflating experience. This isn’t just a sin against mimesis; it’s wholesale mimesis genocide.

It is true that the board-game version of Consulting Detective suffers from the exact same flaws born of its own statelessness. By presenting a case strictly as a collection of extant clues to be put together rather than asking you to ferret them out for yourself — by in effect eliminating from the equation both the story of the crime and the story of the investigation which turned up the clues — the Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers avoid most of these frustrations, at the expense of feeling like drier, more static endeavors. I will say that the infelicities of Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective in general feel more egregious in the computer version — perhaps because the hotter medium of video promotes a depth of immersion in the fiction that makes it feel like even more of a betrayal when the immersion breaks down; or, more prosaically, simply because we feel that the computer ought to be capable of doing a better job of things than it is, while we’re more forgiving of the obvious constraints of a purely analog design.

Of course, it was this very same statelessness that made the design such an attractive one for adaptation to full-motion video in the first place. In other words, the problems with the format which Kinoautomat highlighted in 1967 aren’t quite as easy to dodge around as ICOM perhaps thought. It does feel like ICOM could have done a little better on this front, even within the limitations of full-motion video. Would it have killed them to provide a few clips instead of just one for some of the key scenes, with the one that plays dependent on what the player has already learned? Yes, I’m aware that that has the potential to become a very slippery slope indeed. But still… work with us just a bit, ICOM.

While I don’t want to spend too much more time pillorying this pioneering but flawed game, I do have to point out one more issue: setting aside the problems that arise from the nature of the engine, the cases themselves often have serious problems. They’ve all been shortened and simplified in comparison to the board game, which gives rise to some of the issues. That said, though, it must also be said that not everything in the board game itself is unimpeachable. Holmes’s own narratives of the cases’ solutions, which follow after you complete them by answering all of the questions in the trial phases correctly, are often rife with questionable assumptions and intuitive leaps that would never hold up on an episode of Perry Mason, much less a real trial. At the conclusion of “The Mummy’s Curse,” for instance, he tells us there was “no reason to assume” that the three archaeologists weren’t all killed by the same person. Fair enough — but there is also no reason to assume the opposite, no reason to assume we aren’t dealing with a copycat killer or killers, given that all of the details surrounding the first of the murders were published on the front page of the London Times. And yet Holmes’s entire solution to the case follows from exactly that questionable assumption. It serves, for example, as his logic for eliminating Mrs. Fenwick as a suspect, since she had neither motive nor opportunity to kill the other two archaeologists.

To be fair to Gary Grady and Suzanne Goldberg, this case is regarded by fans of the original board game as the weakest of all ten (it actually shows up as the sixth case there). Why ICOM chose to lead with this of all cases is the greatest mystery of all. Most of the ones that follow are better — but rarely, it must be said, as airtight as our cocky friend Holmes would have them be. But then, in this sense ICOM is perhaps only being true to the Sherlock Holmes canon. For all Holmes’s purported devotion to rigorous logic, Arthur Conan Doyle’s tales never play fair with readers hoping to solve the mysteries for themselves, hinging always on similar logical fallacies and superhuman intuitive leaps. If one chooses to read the classic Sherlock Holmes stories — and many of them certainly are well worth reading — it shouldn’t be in the hope of solving their mysteries before he does.

The three volumes of Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective would, along with a couple of other not-quite-satisfying full-motion-video games, mark the end of the line for ICOM. Faced with the mounting budgets that made it harder and harder for a small developer to survive, they left the gaming scene quietly in the mid-1990s. The catalog of games they left behind is a fairly small one, but includes in Déjà Vu and Consulting Detective two of the most technically significant works of their times. The Consulting Detective games were by no means the only interactive mysteries of the early full-motion-video era; a company called Tiger Media also released a couple of mysteries on CD-ROM, with a similar set of frustrating limitations, and the British publisher Domark even announced but never released a CD-ROM take on one of the old Dennis Wheatley Crime Dossiers. The ICOM mysteries were, however, the most prominent and popular. Flawed though they are, they remain fascinating historical artifacts with much to teach us: about the nature of those days when seeing an actual video clip playing on a monitor screen was akin to magic; about the perils and perhaps some of the hidden potential of building games out of real-world video; about game design in general. In that spirit, we’ll be exploring more experiments with full-motion video in articles to come, looking at how they circumvented — or failed to circumvent — the issues that dogged Kinoautomat, Dragon’s Lair, and Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective alike.

(Sources: the book Media and Participation by Nico Carpentier; Byte of May 1992; Amazing Computing of May 1991, July 1991, March 1992, and May 1992; Amiga Format of March 1991; Amiga Computing of October 1992; CD-ROM Today of July 1993; Computer Gaming World of January 1991, August 1991, June 1992, and March 1993; Family Computing of February 1984; Softline of September 1982; Questbusters of July 1991 and September 1991; CU Amiga of October 1992. Online sources include Joe Pranevich’s interview with Dave Marsh on The Adventure Gamer; the home page of Kinoautomat today; Expo ’67 in Montreal; and Brian Moriarty’s annotated excerpt from Kinoautomat, taken from his lecture “I Sing the Story Electric.”

Some of the folks who once were ICOM Simulations have remastered the three cases from the first volume of the series and now sell them on Steam. The Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective tabletop line is in print again. While I don’t love it quite as much as some do due to some of the issues mentioned in this article, it’s still a unique experience today that’s well worth checking out.)