Like a lot of boys, I grew up loving trains. And like a lot of men, I retain my fascination for them today.

Once upon a time, I could happily spend hours and hours with my Lionel locomotives. They were, back in that era at least, satisfyingly heavy, made out of the same good solid iron as the full-sized models they imitated; they even smoked the same as the real things when you dropped a bit of “smoke fluid” down the stack. I whiled away many an afternoon driving my trains around and around in circles, learning through trial and error just how fast I could take those corners before disaster struck. But for better or for worse, after I was given a Commodore 64 for Christmas in 1984, model railroading fell by the wayside pretty quickly. (How’s that for a parable of the modern homo digitalis?)

Nevertheless, and much to the chagrin of my long-suffering wife, I’m always chomping at the bit to visit any train museum that happens to be within range, whether I’m in Dallas or Nuremberg, Odense or London. I look upon any opportunity to actually ride the rails even more favorably; I love me a vintage tourist railroad, no matter how cheesy. Heck, I still get a little thrill from boarding a train that serves merely as everyday public transportation, something that’s a lot more common here in Europe than it is back in the States. Speaking of which: back in the 1990s, when I was still living in my country of birth, I took a break from my usual backpacker holidays to foreign climes in order to ride the trains of the perpetually underfunded underdog Amtrak all the way from one side of the United States to the other. In marked contrast to most people who have dared such a journey, I’d do it again in a heartbeat. Ditto the trip I once took from Vladivostok to Moscow on the Trans-Siberian Railroad (if and when Russia comes to its senses and stops being a geopolitical Doctor Evil, of course).

Just what is the appeal of trains? I could prattle on here about how they’re a far more environmentally friendly way to travel than planes or cars, but that’s not what causes them to tickle my romantic fancies. The range of feelings that trains evoke in me and in countless others is as rich as it is diverse. Small wonder that they’ve been such a staple of folk and pop music practically since Robert Stephenson’s Rocket first puffed down a track in 1829. The rock and roll of a train became the rhythm of twentieth-century music. A train can carry you away to a better life, or it can carry your baby away to a life without you. A train can be as life-affirming as a heartbeat or as mysterious as a nightmare.

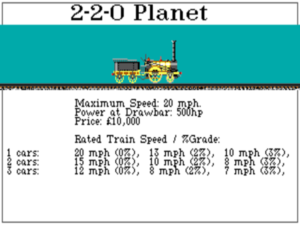

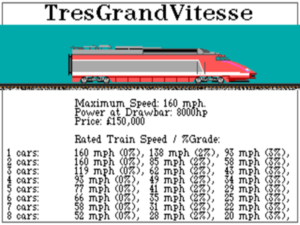

But trains are more than just a set of all-purpose metaphors. They’re also feats of engineering that continue to entrance the little boy in me. The biggest locomotives from the Age of Steam are nothing short of awe-inspiring in their sheer size, artifacts of a lost epoch when high technology meant building on an ever more gigantic rather than an ever more miniaturized scale, when a single piston could be several times the size of a person and a single wheel taller than a willow tree. The newest railroading wonders may not have quite the same nostalgic allure as their coal-fired ancestors, but they too live at the ragged edge of technological feasibility, traveling at more than 300 miles per hour on the magnetic cushions that serve them in lieu of wheels.

Then, too, the historian in me marvels at trains as the wellspring of the modern world. As the first form of fast, efficient mechanized transportation, they produced first-order and knock-on effects that touched every aspect of people’s lives. The very concept of the nation-state as we know it today is largely a tribute to railroads, those steel ties that bind a multiplicity of localities together in a web of travel and trade. The clocks that regulate so much of our lives owe their existence to the emergence of “railroad time,” to which everyone had to learn to synchronize their activities in place of the older, less precise practice of reckoning time by the position of the Sun in the sky. Wide-angle corporate capitalism as we know it today was invented by the great railroad trusts and the oligarchy of so-called “robber barons” who ran them, ruthlessly enough to make Jeff Bezos blush.

Indeed, the facts and figures and lore and legends of railroading are so bottomless that some people get obsessed with the subject almost to the exclusion of all else. Personally, I missed my chance at becoming a hardcore trainspotter as soon as I got my hands on that childhood Commodore 64. That said, the old flame still burns brightly enough that any computer game which focuses on trains is likely to get a little bit of extra attention from me.

I don’t want the game to be too dry or technical; it has to bring the culture of the rails to life, has to make me feel something. Do that, and chances are I’ll be all over your game. Sid Meier’s Railroad Tycoon is one game that did it, marrying an aesthetic presentation that is executed as perfectly as was possible with the computers of 1990 — the theme song that plays over the opening credits is one of the few pieces of game music I occasionally find myself humming at random while I’m doing something else — with a rich and compelling layer of strategic possibility; for my money, it’s rivaled only by Pirates! for the title of Meier’s very best game, beating out even the storied Civilization. I like Railroad Tycoon’s spiritual successor, Chris Sawyer’s Transport Tycoon, a lot as well, even though its focus on trains is somewhat diluted by all the trucks, planes, and ships it throws in. And on a very different note, Jordan Mechner’s adventure game The Last Express uses the last voyage of the Oriental Express from Paris to Constantinople as a metaphor for the passing away of the entire Belle Époque in Europe during the fateful summer of 1914; I find playing it to be an experience of almost unbearable poignancy, filling me with nostalgia for a lost past of dinner jackets, evening gowns, and refined drawing-room conversation that I never actually knew.

Needless to say, then, I wanted to like Railroad Tycoon II even more than I do the typical game that I play for these histories. That always produces a certain trepidation of its own. I’m therefore thrilled to be able to say that — spoiler alert! — it lived up to the high expectations I had for it, enough so as to become the fourth train game to find a place in my intensely idiosyncratic Hall of Fame.

The story of Railroad Tycoon II begins with a young Missourian named Phil Steinmeyer, who in 1994 sold to the Los Angeles-based studio and publisher New World Computing a light wargame called Iron Cross that he had designed and programmed all by himself during evenings and weekends. In some ways, Iron Cross was quite forward-looking, doing a lot of what SSI’s Panzer General did to major commercial success that same year: it personalized the experience of war, by having you create a character, CRPG-style, and lead him through a dozen scenarios, with the possibility of promotion or demotion looming at the end of each of them. Sadly, though, it didn’t fully live up to its concept, failing to find the sweet spot between simplicity and interesting choices that Panzer General had nailed, coming off more like a prototype than a finished product. It was not an injustice that Panzer General revitalized its publisher and spawned a long-running series of similar games, while Iron Cross came and went from store shelves in a scant few months.

Still, it was good enough to become Steinmeyer’s entrée to the games industry. Impressed by his enthusiasm, work ethic, and programming talent, New World’s founder Jon Van Caneghem asked him to stick around as a regular contractor, working remotely — a rarity at that time — from his Midwestern home. Steinmeyer’s next project for New World was another strategy game with CRPG flavorings, one whose legacy would prove far more enduring than that of Iron Cross: he became the main programmer on Van Caneghem’s own Heroes of Might and Magic, which was released in late 1995 to strong sales. He moved even further up in the pecking order with the sequel. On Heroes of Might and Magic II, which was released barely one year after its predecessor, he was credited not only as the lead programmer but as the co-designer, alongside Van Caneghem.

Steinmeyer and New World parted ways just after Heroes II was finished, for reasons that are a little obscure. In a 2000 magazine column, Steinmeyer claimed that “my publisher [i.e., New World] was experiencing financial troubles, and abruptly cut relations with all third-party developers, including me.” I’m actually not aware of any serious financial problems at the company around this time, although it had just been acquired by 3DO, which may have led to a change in policy regarding contractors. In later years, there was significant bad blood between Van Caneghem and Steinmeyer. I don’t know whether it stemmed from the circumstances of the latter’s departure from New World or from subsequent events. (See my postscript below for more on these matters.)

At any rate, Steinmeyer decided to turn PopTop Software, the little one-man company under whose auspices he had been developing games for New World, into a real studio with real employees and a real office, located in St. Louis, Missouri. For the re-imagined PopTop’s first project, he wanted to create another colorful, accessible strategy game, yet one very different from Heroes of Might and Magic in theme and mechanics. He had decided that, with the capabilities of computers having come such a long way since 1990, the time was ripe to build upon the template of legendary designer Sid Meier’s Railroad Tycoon, one of his favorite games of all time. He hired a staff of half a dozen or so others — mostly industry neophytes who were willing to work cheap — to chase the dream alongside him.

His timing was propitious: MicroProse Software, the publisher of the original Railroad Tycoon, wasn’t doing very well and was desperate to raise cash. Having moved on to Transport Tycoon, they saw little commercial potential in returning to a railroad-only strategy game. In fact, they had already rejected Bruce Shelley, Sid Meier’s co-designer on Railroad Tycoon, when he came to them inquiring about the possibility of a direct sequel. Steinmeyer was amazed when MicroProse answered his own initial query not by offering to publish the sequel but by offering to sell him the rights to the name outright. Steinmeyer would later call clinching that deal his most “awesome” single moment during the development of the game.

But it did leave PopTop still in need of a publisher. In early 1998, Steinmeyer signed on with an upstart consortium known as Gathering of Developers — or, to use the acronym that they positively reveled in, G.O.D.

G.O.D. could only have come to exist during the late 1990s, a heady time in gaming, when people like John Carmack and John Romero of DOOM and Quake fame were treated as rock stars by their adoring fans. Scatter-bombing rhetoric that smacked more of a political revolution than a business startup, G.O.D. trumpeted their plan to upend the traditional order in gaming and give control and money to the creatives at the studios instead of the suits at the major publishers. The full story of G.O.D., an incongruous cocktail of naked greed and misplaced idealism, will have to wait for another day. For now, suffice to say that G.O.D. never succeeded in becoming the revolutionary collective its founders wanted it to be, not least because the only people willing and able to pony up the seed capital they needed were the folks at Take Two Interactive, one of the very same traditional publishers that they so loudly professed to despise. For PopTop, however, Take Two’s involvement was ultimately all to the good, as it gave them access to a mature international distribution network of which Railroad Tycoon II would take full advantage.

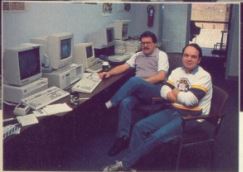

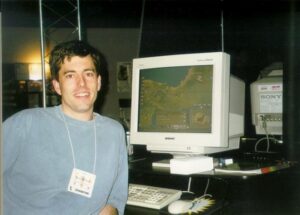

Phil Steinmeyer shows off an early build of Railroad Tycoon II at the 1998 E3 trade show. PopTop’s little booth was all but blotted out and drowned out by a colossus next door devoted to Space Bunnies Must Die!, a schlocky and deafening melange of everything trendy in gaming at the time. In the end, though, Railroad Tycoon II won “Best Strategy Game” at the show and has aged like fine wine, while Space Bunnies has aged like milk.

First released in North America in November of 1998, Railroad Tycoon II was later translated into German, French, Spanish, and Portuguese for the European market, and, even more far-sightedly, into Chinese, Japanese, and Korean to cover the fast-growing consumer economies of East Asia. Combined with a Mac port, a Linux port(!), and reasonably credible ports to the Sony PlayStation and Sega Dreamcast consoles, all of this outreach delivered worldwide sales that may have exceeded 1.5 million copies.

In light of this, it’s remarkable how under-remembered and under-sung Railroad Tycoon II is today. To be sure, you can still buy a “Platinum edition” of the game at the usual digital storefronts. Yet it keeps a weirdly low profile for a title that at the turn of the millennium was the third most successful “builder”-style game ever, trailing only the perennially popular SimCity and Rollercoaster Tycoon, a game by Chris Sawyer of Transport Tycoon fame that was released five months after Railroad Tycoon II.

In this reviewer’s opinion, Railroad Tycoon II was a sparkling creative success as well as a commercial one, making it all the more deserving of remembrance. We’ve seen a fair number of train games built on similar premises in the years since 1998, but I don’t know that we’ve ever seen a comprehensively better one.

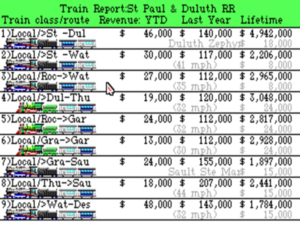

If you haven’t played a “traffic simulator” like this before, the first thing to understand about Railroad Tycoon II is that it’s an extremely abstract simulation, where each trip you see on the screen stands in for hundreds if not thousands of ones that you don’t see. In the opening scenario of the campaign, which begins at the dawn of American railroading in 1830, it will take your little engine that could more than a year to drag two wagons full of passengers from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. The real first locomotives were slow, but they weren’t that slow.

From a purely technical perspective, the most amazing thing about Railroad Tycoon II is its pseudo-3D graphics engine, which lets you rotate the camera to peer around mountains and to zoom way in or way out, depending on whether you need to fuss with the details of track and station placement or take in the big picture of your transport empire. Here we’ve zoomed out far enough to see a goodly chunk of eastern Canada in the late nineteenth century.

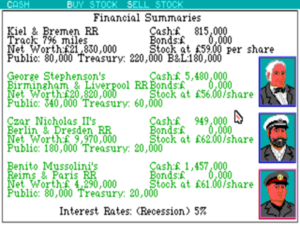

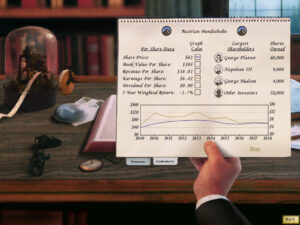

Surrounded by other robber barons as you are, you can’t afford to neglect the financial angle in the more complicated scenarios, where buying and selling stock cleverly can be more important than laying down the most efficient routes.

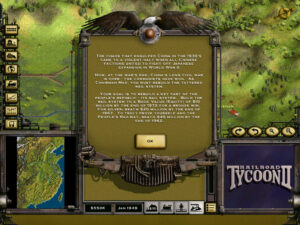

Almost every new scenario in the campaign sent me off to learn more about the real history behind it. Here I’m on the verge of rewriting history by fulfilling the quixotic imperialist dream of the British mining magnate Cecil Rhodes: that of building a single railway line that stretches across the length of Africa, from Cape Town to Cairo.

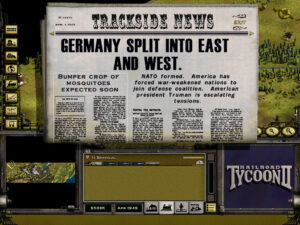

The generic, randomized newspaper messages of the first Railroad Tycoon have been partially replaced by headlines ripped from real history.

With its globalized commercial ambitions, Railroad Tycoon II is careful to steer clear of touchy politics. For example, the era of Chairman Mao’s “Great Leap Forward” for China, which killed twice as many people as the First World War and six times as many as the Holocaust and set Chinese agriculture back by two decades through a combination of malice and incompetence, is presented strictly as an engineering problem.

A comparison of Railroad Tycoon I and II provides a good education in just how much gaming changed during the eight years that separate them. The first game relies heavily on procedural generation to add variety to its handful of maps. There are only a few ways to customize your experience, and no broader framework of progression beyond the “New Game” button.

Railroad Tycoon II, on the other hand, has two 18-scenario campaigns to offer if you include its Second Century expansion pack, plus plenty more singleton hand-crafted scenarios, each with its own historical context, starting and stopping dates, and victory conditions. But if you don’t want to mess with most of that — if you just want to set up a bunch of trains and watch them run — you can do that too by playing in sandbox mode. If, by contrast, you want maximally cut-throat competition, you can play in networked multiplayer mode with some of your mates, engaging in epic business conflicts that can become, as Bob Proctor wrote in his review for Computer Gaming World, “as vicious as any Starcraft game.” In short, Railroad Tycoon II does everything it can to let you turn it into exactly the kind of train game that you most want to play. In my case, that means playing through the campaigns, which I absolutely adore.

The first campaign — the one found in the base game — is divided into thirds: six scenarios taking place in North America, six in Europe, six in the rest of the world. It gives you the sense of living through a huge swath of railroad history, even as it gradually teaches you the ins and outs of what proves to be a deceptively complex game, slowly ramping up the difficulty as it does so. Its scenarios challenge you in a wide variety of different ways, guaranteeing that, by the time you finish all of them, you’ll have engaged with if not completely mastered all of the game’s facets. Some of the scenarios are all about logistics: get a line built from City A to City B before time runs out. Some make you think about your larger role in the economy, by demanding that you adequately service a range of industries. And still others force you to engage with the nitty-gritties of the financial game, by insisting that you acquire a certain corporate or personal net worth by a certain date.

Indeed, in some of the most difficult scenarios, the efficient operation of your railroad provides no more than the seed capital for the real key to victory, your shenanigans on the stock market. If you want to win gold on every scenario — the gold, silver, and bronze victory levels are another way the game lets you set your own goals for yourself — you’ll need to learn to wheel and deal as shrewdly as Cornelius Vanderbilt and as heartlessly as Jay Gould. I recall struggling futilely for days with the thirteenth scenario, which expected me not only to connect Delhi, Calcutta, and Kabul between the years 1850 and 1880 but to be the only surviving railroad left on the Indian subcontinent at the end of that time period if I wanted the gold medal. Then one day I figured out that I could pump and then dump all of my starting company’s stock, leaving it as nothing more than a one-station rump on the map, and use my windfall to buy up a controlling interest in the most dangerous of my two rivals. After that bit of skullduggery, it was smooth sailing. Guile never felt so good.

The Second Century campaign is even more audacious and creative, if a bit shakier in its granular implementation. As the name would imply, it focuses on the later period of railroading that gets somewhat short shrift in the original campaign, beginning during the Great Depression and winding up in a surprisingly dystopic middle 21st century, when global warming and nuclear war have led to civilizational regression on a global scale and you’re now forced to work with old-time steam locomotives once again. Whether this sobering vision will prove prescient remains to be seen, but, in the meanwhile, I can’t say enough admiring things about PopTop’s determination to continue bending and twisting their core game in intriguing new directions. Some of the Second Century scenarios are essentially new games unto themselves, like the one where you have to keep Britain connected and functional during the Blitz, or the one where you have to bring up sufficient troops from the eastern hinterlands of the Soviet Union to resist the Nazi invaders pouring in from the west. Sometimes the scenarios play radically with scale, as in the one that wants you to build a subway system to service a city instead of a railroad network to serve a country or a continent.

Even when giving due consideration to the premise that this is a campaign for veterans, most of the Second Century scenarios are really, really hard — a little bit too hard in my opinion. Less subjectively, there’s a general lack of polish to the second campaign in comparison to the first, with more bugs and glitches on display. In too many of these scenarios, your chances of winning gold are heavily dependent on luck, on the economy turning just the way you need it to just when you need it to. All of this would seem to indicate that the second campaign got a lot less testing than the first, such that PopTop may not have even fully realized how difficult it really was. It’s still worth playing if you finish the first campaign and want more, mind you. I just wouldn’t get too stressed about trying to win gold on every single scenario; I had a lot more fun with it once I accepted that silver or even bronze was good enough and stopped save-scumming and putting myself through all manner of other contortions to bring home the gold.

Inside the scenarios, Phil Steinmeyer made an unusual and refreshing choice in strategy-game sequels, electing not to build upon the blueprint of Railroad Tycoon I by heedlessly piling on additional layers of complexity. In some ways, this sequel is actually simpler than the original, despite the gulf of eight years of fairly frenetic technological development in computing that lies between them. There’s generally less emphasis placed on the mechanics of running your railroad. You must still choose between single or double tracks, and must learn when one or the other is more desirable from a cost-benefit standpoint, but you don’t have to futz around with signals. Two trains running in opposite directions on the same piece of track don’t ram into one another; the one just pulls politely over to a siding that magically appears and waits for the other one to pass by. Likewise, your options for manipulating cargoes and consists[1]In railroad speak, a “consist” — the noun is pronounced with the accent on the first syllable, not on the second as in the verb — is the particular collection of wagons that a given locomotive pulls. at stations are reduced. Most strikingly, tunnels don’t exist at all in Railroad Tycoon II; your only option for getting to the other side of a mountain range is to go around it, to go over it — very slowly! — or to try to find a natural pass through it.

Any way you slice it, the absence of tunnels is kind of weird. Otherwise, though, if you haven’t played the first Railroad Tycoon, you’ll probably never notice the things that Railroad Tycoon II is missing. If you have, you will, and you might even be a bit put out — there’s real joy to be found in getting a complicated network of signals functioning like the proverbial smoothly running machine — but you’ll soon get over it. For Railroad Tycoon II makes up for its simplifications in traffic and cargo management with a lot of meaty sophistication in other areas. The stock market and the management and investment of your corporate and personal wealth are, as I already noted, as vital and rewarding as ensuring that your trains run on time. Meanwhile the specificity of the scenarios turns the game into a form of living history that the more generic, semi-randomized maps found in the original are unable to match. The same tool that PopTop used to build all of the campaign scenarios is included with the game, for those who want to roll their own. There was once a thriving community of scenario builders on the Internet. This is no longer the case, but their leavings can still be found and downloaded. Or, if you buy the Platinum edition of Railroad Tycoon II, you’ll find that a curated selection of 40 of the very best fan-made scenarios is already included.

Last but not least, I have to pay due tribute to the masterful aesthetics of Railroad Tycoon II. There are some contrary old grognards out there who will tell you that audiovisuals don’t matter in strategy games. That’s an opinion that I’ve never shared. Whatever else they may be, computer games are a form of mediated entertainment, and good mediation goes a long way toward making our time spent with them enjoyable and memorable.

Railroad Tycoon II is a fine case in point. Even today, it’s a lovely game just to see and hear, with audiovisuals that immerse you deeply in its subject matter. Every control you manipulate is presented onscreen as a mechanical switch, which, when you click on it, clunks with the same satisfying metallic solidity that I appreciated so much in my Lionel trains as a kid. The video clips that play before the campaign scenarios, mostly sourced from old public-domain newsreel footage, have a graininess that only adds to the period flavor. Playing in the background as you watch your trains puff along is an old-timey blues soundtrack recorded on real acoustic instruments, all wailing harmonicas and resonator guitars, fit to accompany Robert Johnson down to the crossroads for his meeting with the Devil. Each scenario in the campaign is introduced by the game’s one and only voice actor, a crusty geezer who likes to use words like “whippersnapper.”

Now, you could say that all of this is best suited to the Age of Steam, that it’s becoming more than a little anachronistic by the time you’re driving sleek, high-speed electric locomotives through the Chunnel, and you’d be absolutely right. But those sentiments must be tempered by the understanding that Railroad Tycoon II was developed on a shoestring by barely half a dozen people. Phil Steinmeyer used a variety of techniques to compensate for the large team of artists he lacked, such as photographing model trains and importing them instead of trying to draw each locomotive from scratch. He also compensated through the technology of the game engine itself. “Railroad Tycoon II had 3D terrain, good shadows and lighting, and, perhaps most importantly, a higher standard resolution (1024 x 768) than any competing game,” he notes. Back in the day, it pulled off the neat trick of looking like it had had a far bigger development budget than was actually the case.

Today, the combination of clean and evocative audiovisuals, progressive design approaches, and a slick and elegant interface all add up a game that subjectively feels like it’s considerably younger than it really is. The few places where it does show its age — like the lack of an undo function when laying track, which forces you to do the save-and-restore dance if you don’t want to waste tons of money tearing out your mislaid lines — only serve to highlight the general rule of modern elegance. You don’t need to be wearing any nostalgia goggles to appreciate this one, folks. Just fire it up and see where it takes you. If the toot of a steam whistle stirs your soul anything like it can still stir mine, you might have found your latest obsession.

Postscript:

Heroes of Might and Magic II and Railroad Tycoon II: Separated at Birth?

When I first announced that I’d be writing about Railroad Tycoon II, reader eldomtom2 pointed me to some allegations that Greg Fulton, the co-designer of Heroes of Might and Magic III, leveled against Phil Steinmeyer in an online newsletter in 2021. In the course of a somewhat rambling narrative that he admits is rife with hearsay — his association with New World Computing didn’t begin until after Steinmeyer’s had ended — Fulton posits that Steinmeyer kept the Heroes I and II source code he had written for New World and used them as the basis for Railroad Tycoon II. When the first demo of the latter game was released in mid-1998, Fulton discussed with his colleagues how it “felt familiar.” One colleague, he says, then “decompiled the [Railroad Tycoon II] executable and found Heroes II references in the code.” Fulton goes on to say that New World’s corporate parent 3DO sued PopTop and G.O.D. over the alleged code theft:

After some legal wrangling, the judge ordered both NWC and PopTop to produce printouts of the complete source code for HoMM2 and RT2. In the end, it was clear Phil had used the HoMM2 source code to make RT2. In his defense, he asserted [that] JVC [Jon Van Caneghem] had told him he could freely use HoMM2’s game engine. JVC found this claim laughable.

Ultimately, Take Two Interactive, who had a stake in Gathering of Developers, asked 3DO what they wanted to make the lawsuit go away. 3DO asked for 1 million USD… and there it ended.

I’m not sure whether we are to read that last sentence as meaning that 3DO was paid the demanded $1 million or not.

What are we to make of this? At first blush, the accusation against Steinmeyer seems improbable. I can hardly think of two strategy games that are more dissimilar than Heroes of Might and Magic II and Railroad Tycoon II. The one is a turn-based game of conquest set in a fantasy world; the other is a real-time game of business set in the world we live in. The one has a whimsical presentation that lands somewhere between fairy tales and Gygax-era Dungeons & Dragons; the other is solidly, stolidly real-world industrial. And yet, surprising as it is, there does appear to be something to the charges.

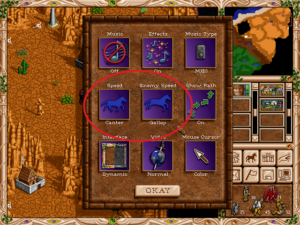

When you start a new standalone scenario in Railroad Tycoon II, the different difficulty levels are represented by icons of horses running at varying speeds. This is a little strange when you stop to think about it. How are such icons a good representation of difficulty? And what are horses doing in our train game at all? I’ve heard the “iron horse” appellation as often as the next person, but this seems to be taking the analogy way too far.

Well, it turns out that the icons are lifted straight out of Heroes of Might and Magic II, where they’re used, much less counterintuitively, to represent the speed at which your and the other players’ armies move on the screen when taking their turns. I can hazard a guess as to what happened here. Steinmeyer probably used the icons as placeholder art at some point — and then, amidst the pressure of crunch, with a hundred other, seemingly more urgent matters to get to, they just never got changed out.

For what it’s worth, these are the only pieces of obvious Heroes II art that I’ve found in Railroad Tycoon II. Yet the presence of the icons does tell us that Steinmeyer really must have been dipping into his old Heroes II project folder in ways that were not quite legally kosher. Based on this evidence, I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn that there are some bits and pieces of code as well in Railroad Tycoon II that started out in the Heroes games. Personally, though, I’m willing to cut him some slack here. The code in question was presumably his code to begin with, after all. And, given how drastically different the games in question are and how low-level the code that he reused must therefore be, the repurposing seems likely to have saved him a few days at the most.

So why was Jon Van Caneghem — a man once described by Neal Halford, a game designer who worked with him for several years at New World, as “terminally mellow” — so much less inclined to be forgiving? I think there may have been some external factors involved. Greg Fulton remembers Caneghem telling him that “Phil Steinmeyer was the main programmer on Heroes 1 and Heroes 2. He offered up ideas, just like Debbie [Caneghem’s wife] did, so I gave him a design credit. After he left, he told anyone who would listen [that] he was the reason Heroes was a success.”

Again, there’s some truth to these accusations. While he was trying to build a buzz around Railroad Tycoon II in the months before its release, Steinmeyer was indeed happy to call himself “the designer of the first two Heroes of Might and Magic games” — full stop. In one preview, Computer Gaming World rather cryptically described him as the designer who “will forever be remembered as the man who saved Heroes of Might and Magic from self-destruction.” In addition to being manifestly incorrect in its core assertion — absolutely nobody remembers Phil Steinmeyer in those terms today — this sentence would seem to imply that Steinmeyer has been telling his journalist friends tales out of school, ones that perhaps don’t cast the schoolmaster at New World in an overly positive light.

I think we can see where this is going. Angered by these exaggerations and possible imprecations — and by no means entirely unjustifiably — Van Caneghem must then have started working to deprecate Steinmeyer’s real contributions to Heroes II, a game on which Van Caneghem had once seen fit to give him a full-fledged co-designer credit alongside himself, not the mere “additional design” credit he received for Heroes I. And he must have told the legal department at 3DO about his other grievance as well, the one he might be able to use to bleed his cocky former colleague. It became, in other words, a good old-fashioned pissing match.

I don’t know whether any of this really did result in Steinmeyer’s camp having to pay Van Caneghem’s camp money, much less precisely what sum changed hands if it did happen. As always, if you have any additional insight on the subject, feel free to chime in down below in the comments. For my own part, though, I think I’ll stop chasing scandals now and go back to playing Railroad Tycoon II. I still have the last few Second Century scenarios to get through…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The book Railroad Tycoon II: The Official Strategy Guide. Computer Gaming World of March 1989, November 1994, February 1997, August 1998, September 1998, December 1998, January 1999, March 1999, August 1999, and October 2001; Next Generation of May 1998.

Online sources include an archive of all 42 “Inside the Sausage Factory” columns that Phil Steinmeyer wrote for Computer Games magazine, the Fanstratics newsletter where Greg Fulton conveys Jon Van Caneghem’s accusations of code theft against Steinmeyer, a 1998 CNET GameCenter Q&A with Bruce Shelley, a 2000 Eurogamer interview with PopTop historical consultant and scenario designer Franz Felsl, and an extended 2007 Gamasutra interview with Mike Wilson.

Where to Get It: Railroad Tycoon Platinum is available as a digital purchase on Steam and GOG.com.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | In railroad speak, a “consist” — the noun is pronounced with the accent on the first syllable, not on the second as in the verb — is the particular collection of wagons that a given locomotive pulls. |

|---|